Exploring the Bidirectional Relationship Between Numerical Cognition and Motor Performance: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Criteria for Considering Studies for This Review

2.1.1. Types of Studies

2.1.2. Types of Participants

2.1.3. Types of Interventions

2.1.4. Types of Outcome Measures

2.2. Search Methods for Identification of Studies

2.2.1. Search Strategy

2.2.2. Search Strategy Structured According to PICO

2.2.3. Selection of Studies

2.2.4. Data Extraction and Management

2.3. Risk of Bias Assessment in Included Studies

2.4. Role of Task Familiarity/Prior Experience

Coding Studies for Task Familiarity and Prior Experience

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.1.1. Design

3.1.2. Year of Publication

3.1.3. Participants and Sample Size

3.1.4. Interventions

3.1.5. Controls

3.1.6. Outcomes

3.1.7. Sources of Funding

3.2. Contextual Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.2.1. Geographic and Institutional Distribution of the Evidence

3.2.2. Motivations and Theoretical Rationales Underpinning the Studies

3.3. Risk of Bias (RoB) Evaluation

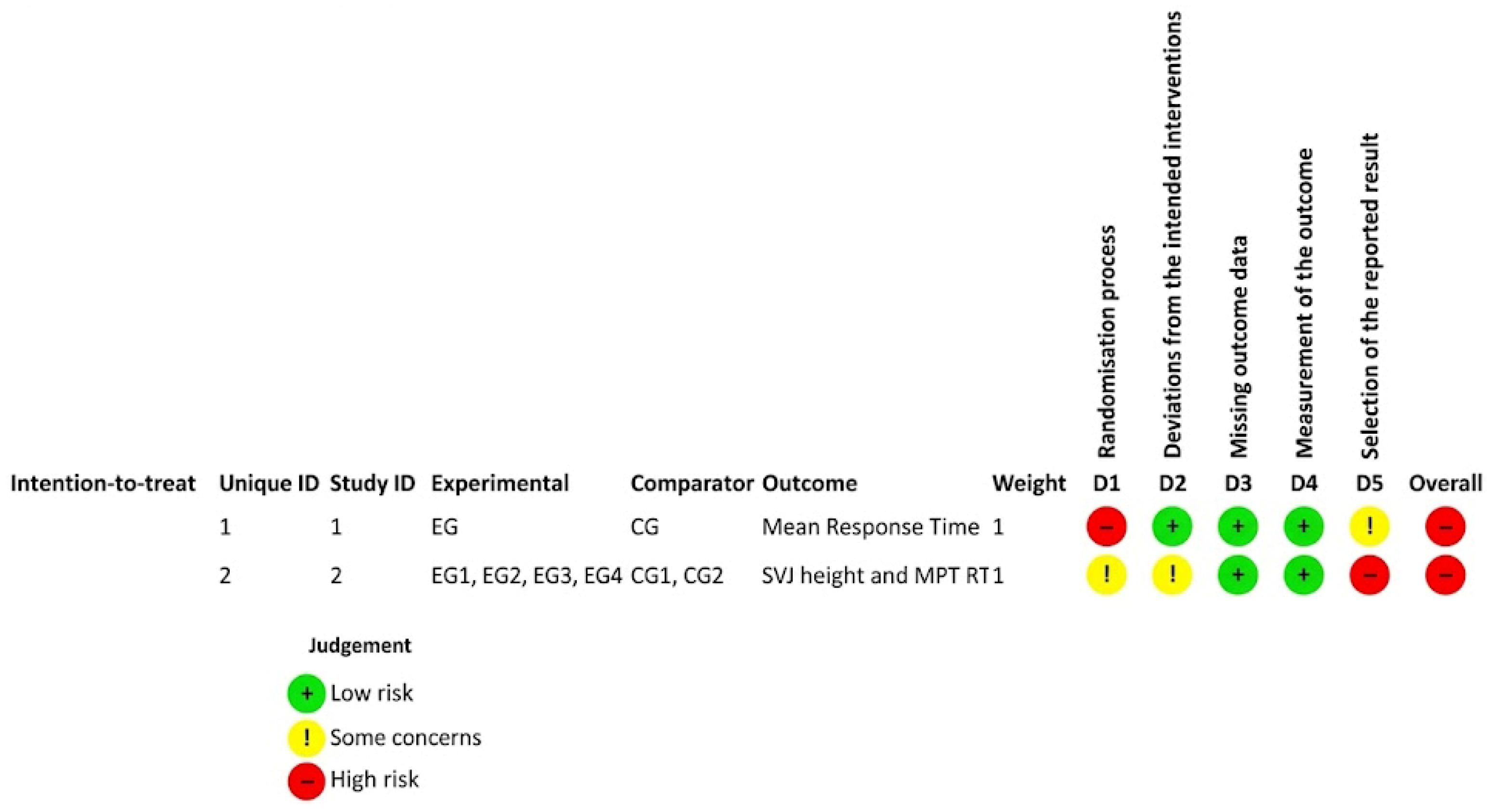

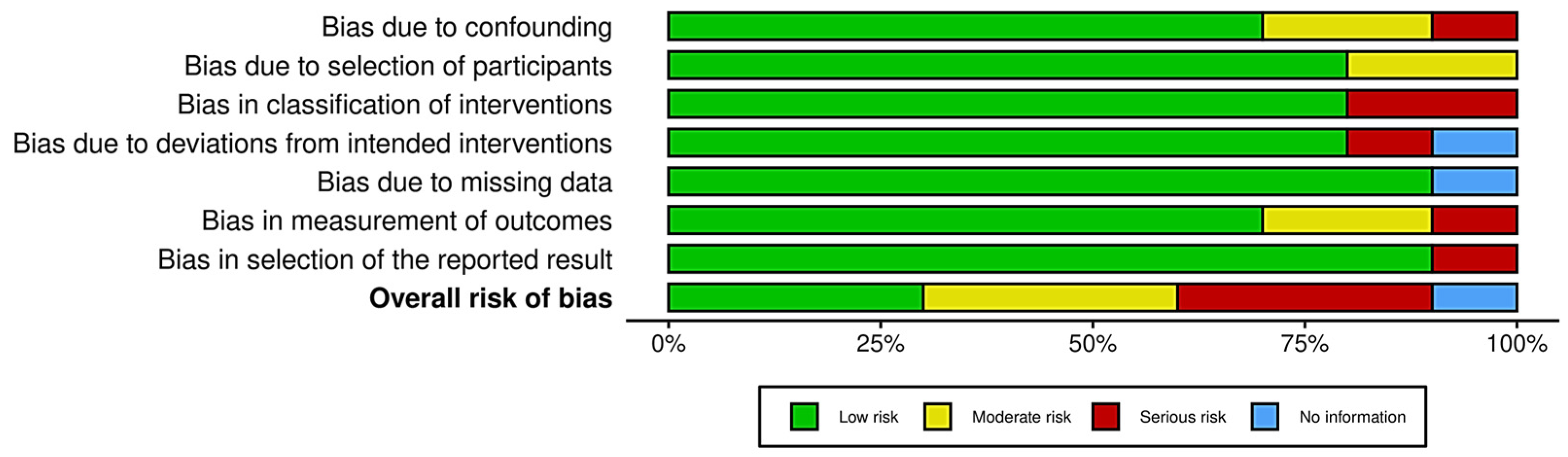

3.3.1. RoB in RCTs

3.3.2. RoB in Non-RCTs

3.4. Effects of Intervention

3.4.1. Numerical Stimuli and Motor Performance

3.4.2. Mental Calculation and Motor Performance

3.4.3. Motor Actions Influencing Numerical Cognition

3.4.4. Influence of Task Familiarity and Prior Experience

3.4.5. Summary of Effects and Reciprocal Relationship

4. Discussion

4.1. Synthesis of Findings by Behavioral Mechanism

4.1.1. Spatial–Numerical and Kinematic Associations

4.1.2. Psychophysiological Facilitation of Motor Output

4.2. The Role of Task Familiarity and Novelty

4.3. Theoretical Implications

4.4. Influence of Task Familiarity on Number–Motor Interactions

4.5. Strengths and Limitations of the Evidence

4.6. Implications for Practice and Research

4.7. Limitations and Certainty of Evidence

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IPS | Intraparietal Sulcus |

| TCM | Triple Code Model |

| ATOM | A Theory of Magnitude |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| RRID | Research Resource Identifier |

| RoB | Risk of Bias |

| RoB 2.0 | Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 Tool |

| ROBINS-I | Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies—of Interventions |

| EMG | Electromyography |

| SNARC | Spatial–Numerical Association of Response Codes |

Appendix A

| Study Name | Study Design | Participants Description | Intervention Description | Control Description | Outcomes Assessed | Funding of the Study | Conflicts of Interest of Study Authors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Randomized Controlled Trials | |||||||

| O. Lindemann et al., 2007 [31] | Non-RCT Trial (within-subjects design) | Exp.1: N = 14 novice healthy students. Exp.2: N = 22 novice healthy students. Exp.3: N = 18 novice healthy students. | Exp.1: reach out and grasp the object with a power or a precision grip depending on the parity of an Arabic digit number. Exp.2: same as Exp.1 but instead of grasping, MPT was required either to the small top or to the large bottom segment of the object. Exp.3: same as Exp.1 but grasping only with thumb and index fingers. | _ | Reaction times for different grips. Maximum grip aperture. | Not provided. | Not provided |

| T. Rabahi et al., 2012 [32] | Non-RCT Trial | Exp.1: N = 43, 28 men (21.5 ± 2.6 y.o.) and 15 women (22.1 ± 1.6 y.o.). Exp.2: N = 30, 16 men (23.7 ± 2.5 y.o.) and 14 women (22.1 ± 2.2 y.o.). Exp.3: reference participants, N = 10 men (22.1 ± 2.4 y.o.). All novice, students. | Participants performed SVJ after cognitive tasks like specific action verb pronunciation(or silent AV), mental calculation (MS), and kinesthetic imagery. | Same experimental procedure as intervention groups but without performing the cognitive tasks. | Height of SVJ. | Not provided. | No conflicts of interest reported. |

| R. Chiou et al., 2012 [33] | Non-RCT Trial (within-subjects design) | N = 13 undergraduates, right-handed, healthy, naive to the purpose of the experiment, experienced in using Arabic digits. | Participants performed visual open-loop grasping towards objects with Arabic digits labels. They had to grasp the object labelled with the odd number if they heard a tone of the higher frequency, whereas they had to grasp the object labelled with an even number if they heard a lower tone frequency. | _ | Evolution of grip aperture relatively to numerical magnitude with different RT and MT evaluated. | Not provided. | Not provided. |

| L. Bensoussan et al., 2012 [34] | Non-RCT Trial (within-subjects design) | N = 10 healthy subjects. 8 right-handed and 2 left-handed. 4 women and 6 men aged 20 to 35 y.o. | Subjects performed wrist isometric extension while receiving mental arithmetic task conditions (subtraction counting backwards in seven-aloud and silent).The period of counting lasted for 10 s and was delimited by two auditory signals. | No MA task was requested during the 10 s elapsing between both signals. The design of the trials was exactly the same in control conditions than in MA conditions. | Mean inter-spike interval (ISI), ISI variability, surface EMG activity, force level, activation of wrist extensor SMU. | Financial support from CNRS. | Not provided. |

| M. Hartmann et al., 2012 [49] | Non-RCT Trial (within-subjects design) | Exp.1: N = 24, 21 female, 3 male, all right-handed. Age ranging from 19 to 35 y.o. Exp.2: N = 24, 4 male, 20 female, all right-handed. Age ranging from 20 to 35 y.o. Exp.3: N = 36 subjects (8 male, all right-handed). Age ranging from 20 to 28 y.o. All are undergraduate students. | Participants positioned on a motion platform. Exp.1: random-number generation task while blindfolded and moving passively in various directions and at stationary. Exp.2: asked to decide as fast as possible whether an auditorily presented number was smaller or larger than 5 Exp.3: asked to decide as fast as possible whether they were moved leftward or rightward. In each trial, either a small (“one, two”) or a large (“eight, nine”) number was presented. | _ | Magnitude of generated numbers. Reaction time (RT) of response on buttons held by subjects. | Swiss National Science Foundation. | Not provided. |

| L. Lugli et al., 2013 [35] | Non-RCT Trial (within-subjects design) | Exp.1: N = 56 healthy university students (30 females, mean age = 22 y.o.). Exp.2: N = 30 new students (16 females, mean age = 20.4 y.o.) from the same pool. | Exp.1: Participants were asked to perform additions or subtractions with ascending or descending movements (Passive (elevator) and active (stairs) modes) for 22 s and to say the result of each calculation aloud. Exp.2: same as in Exp.1. The only difference was that participants were asked to make the calculations while imagining to perform an upward or downward motion. | _ | Congruency between calculation type and movement direction. | MIUR and the European Community, FP7 project ROSSI, Emergence of Communication in Robots through Sensorimotor and Social Interaction. | The authors have declared that no competing interests exist. |

| F. Anelli et al., 2014 [50] | Non-RCT Trial (within-subjects design) | N = 48 undergraduate students (33 female, mean age: 20.3 y.o., SD 3.3). | Participants were asked to perform additions or subtractions for 22 s and to say the result of each calculation aloud while walking leftward or rightward upon the experimenter’s instructions. | _ | Number of correct calculations made during additions and subtractions. | Ricerca Fondamentale Orientata (RFO) funds, University of Bologna, and by the European Community, in FP7 project ROSSI: Emergence of Communication in Robots through Sensorimotor and Social Interaction. | The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. |

| X. Cheng et al., 2015 [36] | Non-RCT Trial (within-subjects design) | Exp.1: N = 64 healthy, right-handed subjects (21 males and 43 females), 21.7 y.o. on average (range: 18–28). Exp.2: N = 30 healthy, right-handed subjects (9 males and 21 females), 23.3 y.o. on average (range: 18–28). All participants were naive to the purpose of the experiment. | Participants were required to report numbers between 1 and 30 as randomly as possible with their eyes covered by a mask in three blocks, i.e., head turns, arm turns and a baseline condition. In Exp.1: Lateral head and arm turns. In Exp.2: Composite body movements with congruent and incongruent directions. | _ | Impact of spatial processing on single numbers representation. Motion-numerical compatibility effect observed for head and arm movements. | Not provided. | The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. |

| R. Rugani et al., 2018 [37] | Non-RCT Trial | N = 23 healthy right-handed students (10 males and 13 females, mean age = 22.74 y.o., SD = 0.75). | Participants sat in front of a monitor, wearing with their right index a small soccer shoe. They were instructed to kick a small ball with their right index towards a soccer goal after observing numbers (A small digit (2), an intermediate digit (5; no-go signal), a large digit (8), and a non-numerical symbol ($)). They refrained from kicking when number five was presented. | _ | Trajectory path efficiency, velocity peak, contact time, time of maximum velocity, time to maximum trajectory height. | SIR grant (Scientific Independence of Young Researchers and “German Academic Exchange Service or DAAD” Funding program: Research Stays for University Academics and Scientists, 2017. | The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. |

| J. Khayat et al., 2021 [38] | Non-RCT Trial | N = 65 healthy undergraduate male students and had normal or corrected to normal vision. | Warm-up session then subjects (CG and EGs) performed three series of six MPMs with 3 mn rest between two consecutive blocks. EGs 1 to 3 realized the first three MPMs of each block remaining immobile in front of a black wall, as in the CG as a baseline. Then they performed three MPMs each after a cognitive task involving mental calculation and number comparison. | CG remained immobile 10 s in front of a black screen after warm-up and training series, and then executed the MPM task. | Response time (RT) of a manual-pointing movement (MPM). | Not provided. | Not provided. |

| Randomized Controlled Trials | |||||||

| O. Bal et al., 2018 [51] | RCT (Pre-post tests) | N = 40 undergraduate healthy Sport Science students aged 19–22 years. | Subjects performed 2 series of 5 mental subtractions (respectively as a Pre-T and as a Post-T). The subjects were instructed to find the correct result of each subtraction as fast as possible. N = 25 subjects performed 5 SVJs with 1 mn rest between 2 consecutive jumps. | Same procedure as EG but after arithmetic series, N = 15 subjects remained seated for 5 min, no physical activity. | Mean of response time (LnRT) of correct responses in mental subtractions before and after performing squat vertical jumps (SVJs). | Not provided. | Not provided. |

| J. Khayat et al., 2019 [39] | RCT | N = 161 healthy undergraduate male students, mean age = 20 y.o., normal BMI, English-speaking. | Subjects were asked to achieve the highest possible SVJ or MPT reaching movement as fast as possible. After warm-up each subject performed three series of either six SVJs, or six MPTs. In each series the first 3 movements were performed without any previous cognitive task (subjects in front of a black screen during 10 s) as a baseline. The three ensuing movements were performed after a cognitive task, i.e., mental subtraction or after reading loudly a number (during 10 s) or an AV. | No cognitive stimulus was given (subjects simply stood in front of a black screen). | SVJ height (cm) and MPT RT (ms). | Not provided. | Not provided. |

References

- Dehaene, S. Origins of Mathematical Intuitions: The Case of Arithmetic. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009, 1156, 232–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindemann, O.; Fischer, M.H. Embodied Number Processing. J. Cogn. Psychol. 2015, 27, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sixtus, E.; Krause, F.; Lindemann, O.; Fischer, M.H. A Sensorimotor Perspective on Numerical Cognition. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2023, 27, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehaene, S. Varieties of Numerical Abilities. Cognition 1992, 44, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehaene, S.; Cohen, L. Towards an Anatomical and Functional Model of Number Processing. Math. Cogn. 1995, 1, 83–120. [Google Scholar]

- Nieder, A. The Neuronal Code for Number. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2016, 17, 366–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschentscher, N.; Hauk, O.; Fischer, M.H.; Pulvermüller, F. You Can Count on the Motor Cortex: Finger Counting Habits Modulate Motor Cortex Activation Evoked by Numbers. Neuroimage 2012, 59–318, 3139–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsalidou, M.; Taylor, M.J. Is 2+2=4? Meta-Analyses of Brain Areas Needed for Numbers and Calculations. Neuroimage 2011, 54, 2382–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauk, O.; Johnsrude, I.; Pulvermüller, F. Somatotopic Representation of Action Words in Human Motor and Premotor Cortex. Neuron 2004, 41, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soylu, F.; Lester, F.K.; Newman, S.D. You Can Count on Your Fingers: The Role of Fingers in Early Mathematical Development. J. Numer. Cogn. 2018, 4, 107–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotzbier, T.J.; Schott, N. Scaffolding Theory of Maturation, Cognition, Motor Performance, and Motor Skill Acquisition: A Revised and Comprehensive Framework for Understanding Motor–Cognitive Interactions across the Lifespan. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1631958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sengupta, A.; Banerjee, S.; Ganesh, S.; Grover, S.; Sridharan, D. The Right Posterior Parietal Cortex Mediates Spatial Reorienting of Attentional Choice Bias. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, V. A Theory of Magnitude: Common Cortical Metrics of Time, Space and Quantity. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2003, 7, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breveglieri, R.; Brandolani, R.; Diomedi, S.; Lappe, M.; Galletti, C.; Fattori, P. Role of the Medial Posterior Parietal Cortex in Orchestrating Attention and Reaching. J. Neurosci. 2025, 45, e0659242024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyon, J.; Bellec, P.; Amsel, R.; Penhune, V.; Monchi, O.; Carrier, J.; Lehéricy, S.; Benali, H. Contributions of the Basal Ganglia and Functionally Related Brain Structures to Motor Learning. Behav. Brain Res. 2009, 199, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hikosaka, O.; Nakamura, K.; Sakai, K.; Nakahara, H. Central Mechanisms of Motor Skill Learning. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2002, 12, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornia, L.; Leonetti, A.; Puglisi, G.; Rossi, M.; Viganò, L.; Della Santa, B.; Simone, L.; Bello, L.; Cerri, G. The Parietal Architecture Binding Cognition to Sensorimotor Integration: A Multimodal Causal Study. Brain 2024, 147, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsalou, L.W. Grounded Cognition. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2008, 59, 617–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M.H.; Shaki, S. Spatial Associations in Numerical Cognition—From Single Digits to Arithmetic. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 2014, 67, 1461–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehaene, S.; Bossini, S.; Giraux, P. The Mental Representation of Parity and Number Magnitude. J. Exp. Psychol. 1993, 122, 371–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, E.M.; Piazza, M.; Pinel, P.; Dehaene, S. Interactions between Number and Space in Parietal Cortex. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2005, 6, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erb, C.D.; Moher, J.; Song, J.-H.; Sobel, D.M. Numerical Cognition in Action: Reaching Behavior Reveals Numerical Distance Effects in 5- to 6-Year-Olds. J. Numer. Cogn. 2018, 4, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, R.; He, H. The Influence of Embodied Cognition on the Perception and Representation of Numbers: A Meta-Analysis. Acta Psychol. 2025, 258, 105180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andres, M.; Seron, X.; Olivier, E. Contribution of Hand Motor Circuits to Counting. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2007, 19, 563–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrocas, R.; Roesch, S.; Gawrilow, C.; Moeller, K. Putting a Finger on Numerical Development—Reviewing the Contributions of Kindergarten Finger Gnosis and Fine Motor Skills to Numerical Abilities. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, W.; Zhang, X. Effect of Finger Gnosis on Young Chinese Children’s Addition Skills. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 544543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsalou, L.W. Grounded Cognition: Past, Present, and Future. Top. Cogn. Sci. 2010, 2, 716–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knops, A. Chapter 11—Neurocognitive Evidence for Spatial Contributions to Numerical Cognition. In Heterogeneity of Function in Numerical Cognition; Henik, A., Fias, W., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 211–232. ISBN 978-0-12-811529-9. [Google Scholar]

- Bjorklund, D.F.; Hubertz, M.J.; Reubens, A.C. Young Children’s Arithmetic Strategies in Social Context: How Parents Contribute to Children’s Strategy Development While Playing Games. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2004, 28, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starkey, P.; Klein, A.; Wakeley, A. Enhancing Young Children’s Mathematical Knowledge through a Pre-Kindergarten Mathematics Intervention. Early Child. Res. Q. 2004, 19, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemann, O.; Abolafia, J.M.; Girardi, G.; Bekkering, H. Getting a Grip on Numbers: Numerical Magnitude Priming in Object Grasping. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 2007, 33, 1400–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabahi, T.; Fargier, P.; Rifai-Sarraj, A.; Clouzeau, C.; Massarelli, R. Motor Performance May Be Improved by Kinesthetic Imagery, Specific Action Verb Production, and Mental Calculation. Neuroreport 2012, 23, 78–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiou, R.Y.-C.; Wu, D.H.; Tzeng, O.J.-L.; Hung, D.L.; Chang, E.C. Relative Size of Numerical Magnitude Induces a Size-Contrast Effect on the Grip Scaling of Reach-to-Grasp Movements. Cortex 2012, 48, 1043–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bensoussan, L.; Duclos, Y.; Rossi-Dur, C. Modulation of Human Motoneuron Activity by a Mental Arithmetic Task. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2012, 31, 999–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lugli, L.; Baroni, G.; Anelli, F.; Borghi, A.M.; Nicoletti, R. Counting Is Easier While Experiencing a Congruent Motion. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e64500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Ge, H.; Andoni, D.; Ding, X.; Fan, Z. Composite Body Movements Modulate Numerical Cognition: Evidence from the Motion-Numerical Compatibility Effect. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugani, R.; Betti, S.; Sartori, L. Numerical Affordance Influences Action Execution: A Kinematic Study of Finger Movement. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayat, J.; Champely, S.; Diab, A.; Sarraj, A.R.; Fargier, P. Effect of Mental Calculation and Number Comparison on a Manual-Pointing Movement. Mot. Control 2020, 25, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayat, J.; Champely, S.; Diab, A.; Rifai Sarraj, A.; Fargier, P. Effect of Mental Calculus on the Performance of Complex Movements. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2019, 66, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Wei, W. Processing Speed Links Approximate Number System and Arithmetic Abilities. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2023, 105, 102318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Meng, Y.; Zhu, L.; Fan, M.; Wang, D.; Zhao, Y. A Review of Methods for Assessment of Cognitive Function in High-Altitude Hypoxic Environments. Brain Behav. 2024, 14, e3418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberstroh, S.; Schulte-Körne, G. The Cognitive Profile of Math Difficulties: A Meta-Analysis Based on Clinical Criteria. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 842391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Núñez-Peña, M.I.; Colomé, À.; González-Gómez, B. The Spatial-Numerical Association of Response Codes (SNARC) Effect in Highly Math-Anxious Individuals: An ERP Study. Biol. Psychol. 2021, 161, 108062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A Web and Mobile App for Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A Revised Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Randomised Trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Non-Randomised Studies of Interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugani, R.; Betti, S.; Ceccarini, F.; Sartori, L. Act on Numbers: Numerical Magnitude Influences Selection and Kinematics of Finger Movement. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, M.; Grabherr, L.; Mast, F.W. Moving Along the Mental Number Line: Interactions Between Whole-Body Motion and Numerical Cognition. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 2012, 38, 1416–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anelli, F.; Lugli, L.; Baroni, G.; Borghi, A.M.; Nicoletti, R. Walking Boosts Your Performance in Making Additions and Subtractions. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, O.; Khayat, J.; Rifai-Sarraj, A.; Fargier, P. Mental calculus and physical education (PE)—Effect of physical exercise. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies, Palma, Spain, 2–4 July 2018; pp. 8006–8014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, T.U.; Rütsche, B.; Wurmitzer, K.; Brem, S.; Ruff, C.C.; Grabner, R.H. Neurocognitive Effects of Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation in Arithmetic Learning and Performance: A Simultaneous tDCS-fMRI Study. Brain Stimul. 2016, 9, 850–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Vist, G.E.; Kunz, R.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Schünemann, H.J. GRADE: An Emerging Consensus on Rating Quality of Evidence and Strength of Recommendations. BMJ 2008, 336, 924–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number of Studies | |

|---|---|

| Total number of studies | 12 |

| Type of study | |

| RCT | 2 |

| non-RCT | 10 |

| Type of intervention | |

| Numerical cognition strategy | 8 |

| Physical activity/motor action | 4 |

| Population gender | |

| Male only | 2 |

| Female only | 0 |

| Combined | 7 |

| Not stated | 3 |

| Sample size | |

| <20 | 2 |

| 20–39 | 1 |

| 40–59 | 5 |

| 60–79 | 1 |

| 80–99 | 2 |

| 100+ | 1 |

| Decade of study published | |

| 2020–onwards | 1 |

| 2010–2019 | 10 |

| 2000–2009 | 1 |

| Comparison (Intervention vs. Control) | Outcomes Assessed | Number of Studies (with References) | Direction of Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Numerical stimuli (digits, magnitudes) prior to motor tasks vs. control/baseline | Reaction times, reach/grasp kinematics, movement trajectories | 7 studies [31,33,36,37,38,39,49] | All studies showed facilitation of motor responses by numerical stimuli (faster RTs, altered kinematics in congruent conditions). |

| Mental calculation/arithmetic tasks prior to motor performance vs. baseline | Jump height, EMG, force, motor accuracy | 7 studies [32,34,35,38,39,50,51] | Positive/facilitation: [32,34,38,39,51]. Negative/interference: [35,50]. Overall: predominantly facilitation. |

| Motor actions (reaching, grasping, jumping, turning) influencing numerical cognition | Arithmetic accuracy, response times to numbers, number-space compatibility | 7 studies [31,32,33,36,37,39,51] | All studies showed that motor actions biased numerical cognition: congruent movements improved performance, incongruent impaired it. |

| Symbolic vs. non-symbolic control conditions | RTs and movement kinematics | 1 study [37] | Only numerical symbols modulated motor performance; non-symbolic controls had no effect. |

| Congruent vs. incongruent number–movement pairings | RTs, calculation accuracy | 3 studies [35,36,38] | Congruent pairings facilitated responses; incongruent pairings slowed or reduced accuracy. |

| Motor imagery vs. physical execution | Jump height, timing | 1 study [32] | Mental calculation facilitated both imagery and execution, with weaker effects in imagery. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rached, E.; Allaw, J.; Khayat, J.; Karaki, H.; Diab, A.; Pinti, A.; Rifai Sarraj, A. Exploring the Bidirectional Relationship Between Numerical Cognition and Motor Performance: A Systematic Review. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 1331. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121331

Rached E, Allaw J, Khayat J, Karaki H, Diab A, Pinti A, Rifai Sarraj A. Exploring the Bidirectional Relationship Between Numerical Cognition and Motor Performance: A Systematic Review. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1331. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121331

Chicago/Turabian StyleRached, Eliane, Jihan Allaw, Joy Khayat, Hassan Karaki, Ahmad Diab, Antonio Pinti, and Ahmad Rifai Sarraj. 2025. "Exploring the Bidirectional Relationship Between Numerical Cognition and Motor Performance: A Systematic Review" Brain Sciences 15, no. 12: 1331. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121331

APA StyleRached, E., Allaw, J., Khayat, J., Karaki, H., Diab, A., Pinti, A., & Rifai Sarraj, A. (2025). Exploring the Bidirectional Relationship Between Numerical Cognition and Motor Performance: A Systematic Review. Brain Sciences, 15(12), 1331. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121331