EEG Microstates During Multisensory Stimulation: Assessing the Severity of Disorders of Consciousness and Distinguishing the Minimally Conscious State

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. EEG Processing

2.4. Microstate Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Result

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

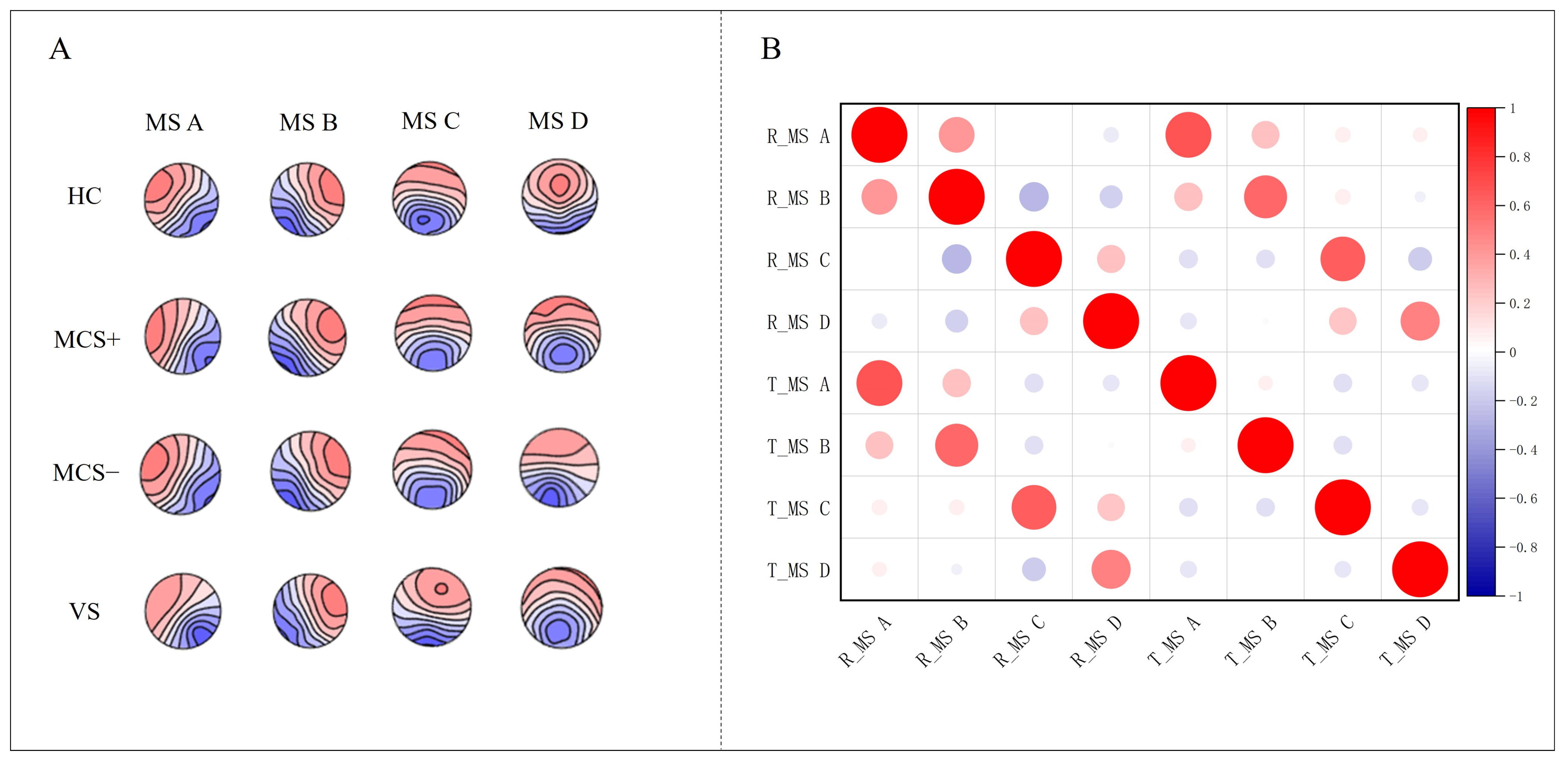

3.2. Microstate Topographic Map

3.3. Rest State Microstate D Parameter

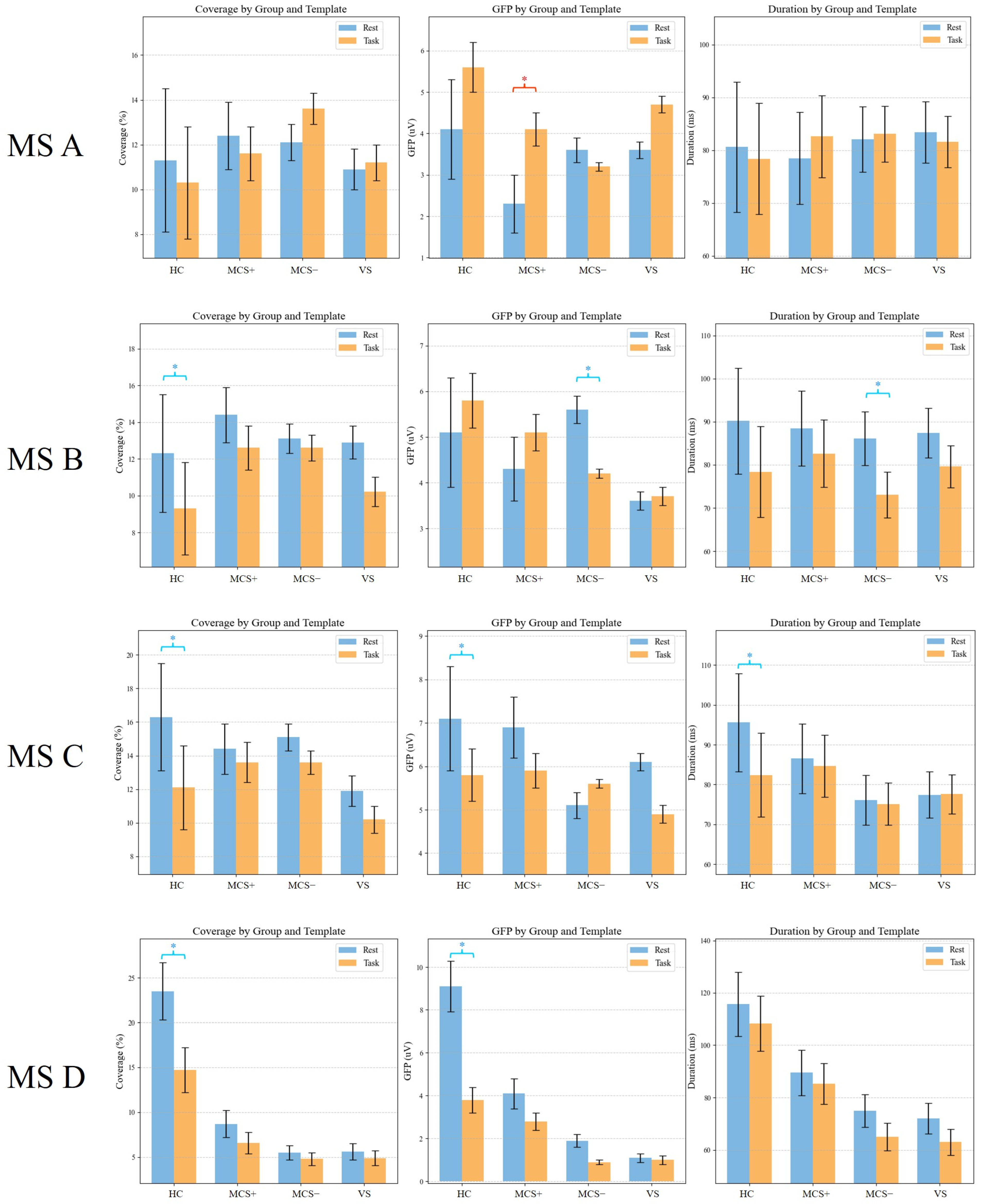

3.4. Differences in Global Templates Between the Task-State and Resting-State

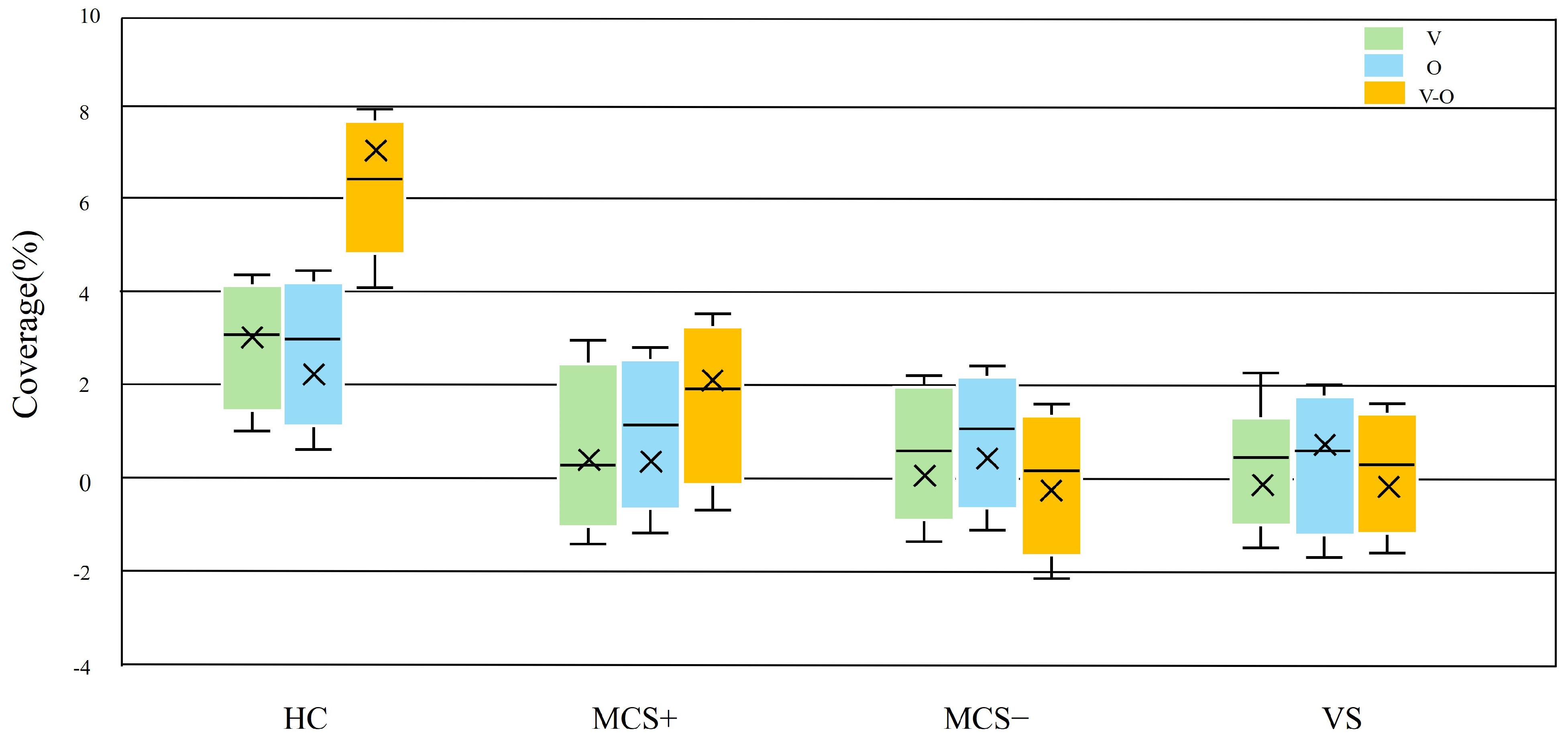

3.5. Dynamic Response of Task-State Microstate D

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vechorko, V.I.; Zimin, A.A.; Obuhova, E.V. Assessment of the Level of Consciousness in Real Clinical Practice Using the Glasgow Coma Scale and the Four Scale. ЭНИ Забайкальский медицинский вестник 2024, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodien, Y.G.; Barra, A.; Temkin, N.R.; Barber, J.; Foreman, B.; Vassar, M.; Robertson, C.; Taylor, S.R.; Markowitz, A.J.; Manley, G.T.; et al. Diagnosing Level of Consciousness: The Limits of the Glasgow Coma Scale Total Score. J. Neurotrauma 2021, 38, 3295–3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelen, L.A.; Lythgoe, D.J.; Jackson, J.B.; Howard, M.A.; Stone, J.M.; Egerton, A. Imaging Brain Glx Dynamics in Response to Pressure Pain Stimulation: A 1H-fMRS Study. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 681419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacino, J.T.; Schnakers, C.; Rodriguez-Moreno, D.; Kalmar, K.; Schiff, N.; Hirsch, J. Behavioral Assessment in Patients with Disorders of Consciousness: Gold Standard or Fool’s Gold? In Progress in Brain Research; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 177, pp. 33–48. ISBN 978-0-444-53432-3. [Google Scholar]

- Schnakers, C.; Vanhaudenhuyse, A.; Giacino, J.; Ventura, M.; Boly, M.; Majerus, S.; Moonen, G.; Laureys, S. Diagnostic Accuracy of the Vegetative and Minimally Conscious State: Clinical Consensus versus Standardized Neurobehavioral Assessment. BMC Neurol. 2009, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosseries, O.; Zasler, N.D.; Laureys, S. Recent Advances in Disorders of Consciousness: Focus on the Diagnosis. Brain Inj. 2014, 28, 1141–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guldenmund, P.; Stender, J.; Heine, L.; Laureys, S. Mindsight: Diagnostics in Disorders of Consciousness. Crit. Care Res. Pract. 2012, 2012, 624724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, D.; Antony, B. Ashwagandha: Potential Drug Candidate from Ancient Ayurvedic Remedy, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025; ISBN 978-1-032-67596-1. [Google Scholar]

- Wannez, S.; Heine, L.; Thonnard, M.; Gosseries, O.; Laureys, S. Coma Science Group collaborators The Repetition of Behavioral Assessments in Diagnosis of Disorders of Consciousness. Ann. Neurol. 2017, 81, 883–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtaugh, B.; Shapiro Rosenbaum, A. Clinical Application of Recommendations for Neurobehavioral Assessment in Disorders of Consciousness: An Interdisciplinary Approach. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1129466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacino, J.T.; Katz, D.I.; Schiff, N.D.; Whyte, J.; Ashman, E.J.; Ashwal, S.; Barbano, R.; Hammond, F.M.; Laureys, S.; Ling, G.S.F.; et al. Practice Guideline Update Recommendations Summary: Disorders of Consciousness: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology; the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine; and the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research. Neurology 2018, 91, 450–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastrovito, D.; Hanson, C.; Hanson, S. Temporal Dynamics of Activity in Default Mode Network Suggest a Role in Top-Down Processing for Trial Responses. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sestieri, C.; Corbetta, M.; Romani, G.L.; Shulman, G.L. Episodic Memory Retrieval, Parietal Cortex, and the Default Mode Network: Functional and Topographic Analyses. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 4407–4420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greicius, M.D.; Krasnow, B.; Reiss, A.L.; Menon, V. Functional Connectivity in the Resting Brain: A Network Analysis of the Default Mode Hypothesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Q.; Lu, G.; Zhang, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, Z.; Guo, Y.; Li, K.; Ding, M.; Liu, Y. Granger Causal Influence Predicts BOLD Activity Levels in the Default Mode Network. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2011, 32, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishida, K.; Razavi, N.; Jann, K.; Yoshimura, M.; Dierks, T.; Kinoshita, T.; Koenig, T. Integrating Different Aspects of Resting Brain Activity: A Review of Electroencephalographic Signatures in Resting State Networks Derived from Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Neuropsychobiology 2015, 71, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoli, E.; Devara, E.; Dang, H.Q.; Rabinovich, R.; Mathura, R.K.; Anand, A.; Pascuzzi, B.R.; Adkinson, J.; Bijanki, K.R.; Sheth, S.A.; et al. Default Mode Network Spatio-Temporal Electrophysiological Signature and Causal Role in Creativity. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, M.; Arcara, G.; Porcaro, C.; Mantini, D. Hemodynamic Correlates of Electrophysiological Activity in the Default Mode Network. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, V.; Mitchell, D.J.; Duncan, J. Role of the Default Mode Network in Cognitive Transitions. Cereb. Cortex 2018, 28, 3685–3696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, B.; Rowe, J.B. Functional Biomarkers for Neurodegenerative Disorders Based on the Network Paradigm. Prog. Neurobiol. 2011, 95, 505–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araña-Oiarbide, G.; Daws, R.E.; Lorenz, R.; Violante, I.R.; Hampshire, A. Preferential Activation of the Posterior Default-Mode Network with Sequentially Predictable Task Switches. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, C.M.; Koenig, T. EEG Microstates as a Tool for Studying the Temporal Dynamics of Whole-Brain Neuronal Networks: A Review. NeuroImage 2018, 180, 577–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voegler, R.; Becker, M.P.I.; Nitsch, A.; Miltner, W.H.R.; Straube, T. Aberrant Network Connectivity during Error Processing in Patients with Schizophrenia. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2016, 41, E3–E12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houck, J.M.; Çetin, M.S.; Mayer, A.R.; Bustillo, J.R.; Stephen, J.; Aine, C.; Cañive, J.; Perrone-Bizzozero, N.; Thoma, R.J.; Brookes, M.J.; et al. Magnetoencephalographic and Functional MRI Connectomics in Schizophrenia via Intra- and Inter-Network Connectivity. NeuroImage 2017, 145, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Xie, Q.; Ma, Q.; Urbin, M.A.; Liu, L.; Weng, L.; Huang, X.; Yu, R.; Li, Y.; Huang, R. Distinct Interactions between Fronto-Parietal and Default Mode Networks in Impaired Consciousness. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eryilmaz, H.; Pax, M.; O’Neill, A.G.; Vangel, M.; Diez, I.; Holt, D.J.; Camprodon, J.A.; Sepulcre, J.; Roffman, J.L. Network Hub Centrality and Working Memory Performance in Schizophrenia. Schizophr 2022, 8, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunterngchit, C.; Baniata, L.H.; Albayati, H.; Baniata, M.H.; Alharbi, K.; Alshammari, F.H.; Kang, S. A Hybrid Convolutional–Transformer Approach for Accurate Electroencephalography (EEG)-Based Parkinson’s Disease Detection. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasool, A.; Aslam, S.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Chen, W. Deep Neurocomputational Fusion for ASD Diagnosis Using Multi-Domain EEG Analysis. Neurocomputing 2025, 641, 130353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, T.-P.; Makeig, S.; Westerfield, M.; Townsend, J.; Courchesne, E.; Sejnowski, T.J. Removal of Eye Activity Artifacts from Visual Event-Related Potentials in Normal and Clinical Subjects. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2000, 111, 1745–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delorme, A.; Makeig, S. EEGLAB: An Open Source Toolbox for Analysis of Single-Trial EEG Dynamics Including Independent Component Analysis. J. Neurosci. Methods 2004, 134, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagabhushan Kalburgi, S.; Kleinert, T.; Aryan, D.; Nash, K.; Schiller, B.; Koenig, T. MICROSTATELAB: The EEGLAB Toolbox for Resting-State Microstate Analysis. Brain Topogr. 2024, 37, 621–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulsen, A.T.; Pedroni, A.; Langer, N.; Hansen, L.K. Microstate EEGlab Toolbox: An Introductory Guide. bioRxiv 2018, 289850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, N.; Pei, Y.; Carrette, E.; Aldenkamp, A.P.; Pechenizkiy, M. EEG-Based Classification of Epilepsy and PNES: EEG Microstate and Functional Brain Network Features. Brain Inf. 2020, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, C.M.; Brechet, L.; Schiller, B.; Koenig, T. Current State of EEG/ERP Microstate Research. Brain Topogr. 2024, 37, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, A.; Zahediasl, S. Normality Tests for Statistical Analysis: A Guide for Non-Statisticians. Int. J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 10, 486–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Pandey, C.; Singh, U.; Gupta, A.; Sahu, C.; Keshri, A. Descriptive Statistics and Normality Tests for Statistical Data. Ann. Card Anaesth. 2019, 22, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Cutsem, J.; De Pauw, K.; Marcora, S.; Meeusen, R.; Roelands, B. A Caffeine-Maltodextrin Mouth Rinse Counters Mental Fatigue. Psychopharmacology 2018, 235, 947–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seutemann, F. Verlauf der Stressreagibilität bei Patientinnen mit Komplexen Traumafolgestörungen; Georg-August-University Göttingen: Göttingen, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Siewiera, K.; Labieniec-Watala, M.; Wolska, N.; Kassassir, H.; Watala, C. Sample Preparation as a Critical Aspect of Blood Platelet Mitochondrial Respiration Measurements—The Impact of Platelet Activation on Mitochondrial Respiration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using Lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, T.; Prichep, L.; Lehmann, D.; Sosa, P.V.; Braeker, E.; Kleinlogel, H.; Isenhart, R.; John, E.R. Millisecond by Millisecond, Year by Year: Normative EEG Microstates and Developmental Stages. NeuroImage 2002, 16, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Li, R.; Zhang, R.; Liu, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, D.; Shan, Q.; Wang, X.; Hu, Y. Dynamic Changes of Brain Activity in Patients with Disorders of Consciousness During Recovery of Consciousness. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 878203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liuzzi, P.; Mannini, A.; Hakiki, B.; Campagnini, S.; Romoli, A.M.; Draghi, F.; Burali, R.; Scarpino, M.; Cecchi, F.; Grippo, A. Brain Microstate Spatio-Temporal Dynamics as a Candidate Endotype of Consciousness. NeuroImage Clin. 2024, 41, 103540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| GROUP | HC (n = 9) | MCS+ (n = 6) | MCS− (n = 6) | VS (n = 6) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 28.7 ± 10.4 | 32.6 ± 8.4 | 31.5 ± 8.4 | 28.5 ± 8.4 | >0.05 |

| Gender (female/male) | 6/3 | 4/2 | 3/3 | 3/3 | >0.05 |

| Mean education | 12.5 ± 2.1 | 11.5 ± 3.1 | 10.6 ± 3.1 | 10.8 ± 2.1 | >0.05 |

| CRS-R | 22.8 ± 0.1 | 17.8 ± 1.17 | 10.3 ± 1.03 | 6.2 ± 1.72 | F = 337.76 p < 0.001 |

| Group | Template | Coverage (%) | GFP (μV) | Duration (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC | Rest | 11.8 ± 3.9 | 4.1 ± 1.3 | 80.6 ± 12.2 |

| Task | 10.2 ± 2.4 | 5.5 ± 0.6 | 78.3 ± 10.5 | |

| MCS+ | Rest | 12.2 ± 2.1 | 2.4 ± 0.6 | 78.6 ± 8.7 |

| Task | 11.8 ± 1.7 | 4.1 ± 0.4 * | 82.6 ± 5.3 | |

| MCS− | Rest | 12.1 ± 1.1 | 3.6 ± 0.2 | 81.4 ± 5.3 |

| Task | 13.7 ± 0.8 | 3.2 ± 0.1 | 82.9 ± 4.2 | |

| VS | Rest | 11.1 ± 1.1 | 3.5 ± 0.2 | 82.6 ± 5.9 |

| Task | 11.5 ± 0.5 | 4.6 ± 0.2 | 81.3 ± 5.8 |

| Group | Template | Coverage (%) | GFP (μV) | Duration (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC | Rest | 12.1 ± 3.4 * | 5.1 ± 1.4 | 90.6 ± 11.9 |

| Task | 9.6 ± 2.9 | 5.7 ± 0.8 | 78.3 ± 10.5 | |

| MCS+ | Rest | 14.2 ± 1.8 | 4.2 ± 0.8 | 88.5 ± 10.7 |

| Task | 12.9 ± 0.9 | 5.1 ± 0.4 | 83.2 ± 7.6 | |

| MCS− | Rest | 13.2 ± 0.8 | 5.6 ± 0.3 * | 87.1 ± 6.3 * |

| Task | 12.8 ± 0.6 | 4.2 ± 0.1 | 74.6 ± 3.9 | |

| VS | Rest | 13.1 ± 0.8 | 3.6 ± 0.2 | 88.1 ± 5.9 |

| Task | 10.2 ± 0.9 | 3.7 ± 0.2 | 79.8 ± 5.3 |

| Group | Template | Coverage (%) | GFP (μV) | Duration (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC | Rest | 16.1 ± 3.2 * | 7.1 ± 1.2 * | 97.6 ± 10.2 * |

| Task | 12.1 ± 2.3 | 5.8 ± 0.7 | 82.3 ± 11.9 | |

| MCS+ | Rest | 14.2 ± 1.8 | 6.9 ± 0.6 | 87.5 ± 8.4 |

| Task | 13.8 ± 1.1 | 5.8 ± 0.5 | 85.2 ± 7.3 | |

| MCS− | Rest | 14.5 ± 0.5 | 5.2 ± 0.3 | 76.1 ± 6.3 |

| Task | 13.7 ± 0.6 | 5.6 ± 0.1 | 75.2 ± 5.2 | |

| VS | Rest | 11.9 ± 1.1 | 6.1 ± 0.3 | 77.2 ± 5.9 |

| Task | 10.7 ± 0.6 | 4.8 ± 0.3 | 77.6 ± 5.6 |

| Group | Template | Coverage (%) | GFP (μV) | Duration (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC | Rest | 23.5 ± 3.2 * | 14.7 ± 4.1 * | 115.6 ± 10.2 |

| Task | 14.7 ± 4.1 | 3.8 ± 1.1 | 108.3 ± 12.5 | |

| MCS+ | Rest | 8.7 ± 1.2 | 4.1 ± 0.9 | 89.5 ± 8.7 |

| Task | 6.6 ± 1.1 | 2.8 ± 0.7 | 85.2 ± 7.3 | |

| MCS− | Rest | 5.5 ± 1.2 | 1.9 ± 0.6 | 75.1 ± 6.3 |

| Task | 4.8 ± 0.8 | 0.9 ± 0.8 | 65.2 ± 7.2 | |

| VS | Rest | 5.6 ± 0.9 | 1.1 ± 0.7 | 72.1 ± 5.9 |

| Task | 4.9 ± 0.6 | 1.0 ± 0.8 | 63.2 ± 7.3 |

| Template | Indicator | HC | MCS+ | MCS−/VS | Group-F | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rest | R2 | 0.78 ± 0.06 | 0.52 ± 0.08 | 0.31 ± 0.05 | 28.7 | <0.05 |

| R-S-D | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | 4.8 ± 0.7 | 32.4 | <0.05 | |

| Task | R2 | 0.55 ± 0.07 | 0.38 ± 0.06 | 0.22 ± 0.04 | 19.5 | <0.05 |

| R-S-D | 3.4 ± 0.4 | 4.7 ± 0.6 | 6.1 ± 0.9 | 25.6 | <0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Min, T.; Sun, F.; Tong, J.; Chen, Z.; Yang, Y.; Han, S. EEG Microstates During Multisensory Stimulation: Assessing the Severity of Disorders of Consciousness and Distinguishing the Minimally Conscious State. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 1306. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121306

Min T, Sun F, Tong J, Chen Z, Yang Y, Han S. EEG Microstates During Multisensory Stimulation: Assessing the Severity of Disorders of Consciousness and Distinguishing the Minimally Conscious State. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1306. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121306

Chicago/Turabian StyleMin, Tao, Fangfang Sun, Jiaxue Tong, Zixuan Chen, Yong Yang, and Shuai Han. 2025. "EEG Microstates During Multisensory Stimulation: Assessing the Severity of Disorders of Consciousness and Distinguishing the Minimally Conscious State" Brain Sciences 15, no. 12: 1306. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121306

APA StyleMin, T., Sun, F., Tong, J., Chen, Z., Yang, Y., & Han, S. (2025). EEG Microstates During Multisensory Stimulation: Assessing the Severity of Disorders of Consciousness and Distinguishing the Minimally Conscious State. Brain Sciences, 15(12), 1306. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121306