1. Introduction

Since the seminal work by Mesulam [

1], who described primary progressive aphasia (PPA) as a neurodegenerative syndrome with progressive language impairment, extensive research has been carried out in the field (e.g., [

2,

3,

4]). Since then, Gorno-Tempini and colleagues [

5] established the International Consensus Criteria for diagnosing and classifying PPA into three main variants: the semantic variant (svPPA), the logopenic variant (lvPPA), and the nonfluent/agrammatic variant (nfvPPA). The svPPA is characterized primarily by severe anomia, deficits in semantic knowledge and comprehension, and surface dysgraphia and dyslexia. In contrast, lvPPA involves milder lexical retrieval impairments and deficits in sentence repetition. Finally, nfvPPA is characterized by effortful speech, which may be agrammatic and/or apraxic, along with syntactic comprehension difficulties. However, some patients exhibit mixed symptoms that do not fit into any of the three previously mentioned variants, as noted by Gorno-Tempini et al. [

5].

However, most studies have focused on English-speaking individuals and monolingual speakers. Only more recently, researchers have worked on the presentation, assessment, and treatment of PPA in other languages (among others, [

6,

7,

8]) and in bilingual speakers (see [

9] and references therein). Despite these efforts, research on minoritized languages remains limited. This is the case for Catalan (see [

10] for discussion of its minoritized status), which lacks studies characterizing PPA in Catalan speakers, as well as adapted assessment tools and treatment for this population.

So far, the few studies involving Catalan speakers with PPA have approached them within a bilingual framework, focusing mainly on the comparison of Catalan with the majority language, primarily Spanish [

11,

12,

13], or treating Catalan and Spanish speakers as a single undifferentiated group [

14]. While previous studies provide valuable insights, there remains a need for approaches that specifically address the unique assessment and treatment challenges faced by Catalan speakers. Additionally, previous studies focus only on one ability, such as naming or speech. As a result, the language deficits of people with PPA (pwPPA) have not yet been described in Catalan.

This work aims to contribute to addressing that gap, focusing on the assessment and diagnosis of PPA in Catalan-speaking individuals. Standardized tools are crucial for characterizing patients’ language deficits, understanding the nature of their impairments, and designing tailored interventions. To address the lack of standardized assessment tools for Catalan-speaking pwPPA, we propose using the

Comprehensive Aphasia Test in Catalan (CAT-CAT) [

15,

16]. The CAT-CAT is the only available tool with published normative data for Catalan to date [

17] and has demonstrated sensitivity to subtle language deficits in post-stroke aphasia [

18,

19]. It is a comprehensive test that evaluates a wide range of language abilities across modalities, including those necessary to diagnose PPA, such as naming, comprehension, production, repetition, reading, and writing [

20]. Previous studies have found significant overlap between PPA and post-stroke aphasia (e.g., [

21]); thus, despite not being specifically designed for PPA, the CAT-CAT may represent a valuable, practical tool for standardized assessment and monitoring of language deficits in Catalan-speaking pwPPA.

The CAT also has the advantage of having been adapted to multiple languages [

22], such as Turkish, Basque or Arabic [

23,

24,

25], and studies have shown that the different versions are comparable (e.g., [

26]), facilitating more tailored assessment of bilingual speakers. Moreover, it was developed to assess and monitor language abilities over time [

27], making it a potentially suitable tool for tracking the progressive changes characteristic of this syndrome. Based on these features, we expect that the CAT-CAT will detect linguistic deficits in pwPPA. Moreover, we expect Catalan-speaking pwPPA to present with more severe and less specific deficits, likely due to the lack of standardized tests, which often results in delayed diagnoses.

Therefore, this study evaluates the utility of the CAT-CAT for assessing PPA in Catalan-dominant bilinguals, a population often overlooked in the development of standardized assessments. We administered the CAT-CAT to four participants clinically diagnosed with PPA through informal Spanish-language assessments and general cognitive screening tools. Our aims were to: (i) determine the test’s sensitivity to PPA-linguistic deficits (e.g., anomia) in order to evaluate its potential clinical utility as a diagnostic tool; (ii) describe detailed linguistic profiles, sometimes overlooked in non-standardized examinations, that are crucial for accurate variant identification and intervention planning; (iii) conduct a detailed micro-quantitative and qualitative analysis of responses—particularly error types and speech—to characterize the language impairments exhibited by bilingual participants, given that results cannot be validated due to the absence of standardized assessment tools in Catalan; and (iv) provide, for the first time, a description of language deficits in Catalan-speaking pwPPA, addressing a significant gap in the literature.

3. Results

3.1. Overall Results and Severity Profiles

The performance of the four participants on the CAT-CAT varied across tasks, but all obtained scores below the cutoff thresholds in several subtests (highlighted in

Table 2 in bold), indicating impaired performance across various language domains. The results of the language battery showed that all participants had deficits in naming objects, as well as in comprehending spoken words and sentences, and in writing to dictation. In addition, their form scores on written descriptions were below the threshold. As for their results on the cognitive screen, all participants performed below the normal threshold on the semantic word fluency subtest, which also evaluates verbal skills, and on the arithmetic subtest, which assesses acalculia.

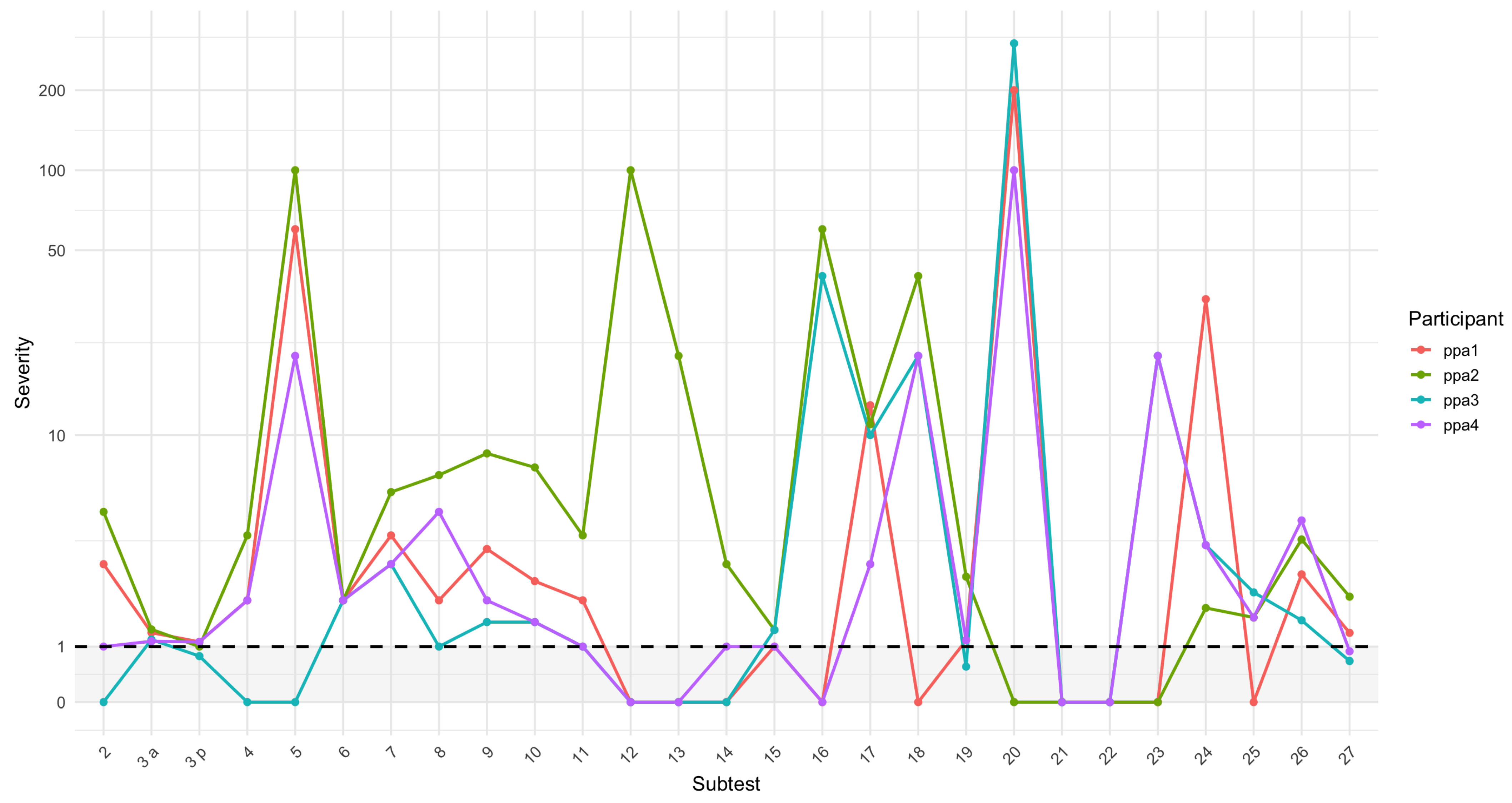

The deficits observed across language domains, however, varied in severity. Since the different subtests also differ in difficulty, we calculated the severity index scores for each participant and subtest (

Figure 1; see

Appendix A.1 for the raw scores). Scores from 0 to 1 reflect unimpaired performance: a score of 0 indicates that the participant obtained the maximum score, whereas a score of 1 corresponds to performance at the cutoff level. Scores above 1 indicate increasing levels of impairment. Results from subtests 5, 12, 13, 16, 18, 21, 22, and 23 should be interpreted with caution and with respect to raw scores, due to ceiling effects in the normative sample that in some cases inflated severity values.

With these considerations in mind, we examined the distinct severity profiles for each participant. For instance, participant PPA2 exhibited the most severe impairments, with difficulties across all linguistic domains except for reading subtests (20–23), where he performed at ceiling. His most severe deficits were in comprehension (subtests 7–11) and production (subtests 19 and 27). Cognitive screening also revealed deficits in semantic memory tasks (subtests 2 and 4), motor abilities (5) and calculation skills (6). In contrast, PPA3 presented with more specific and less severe deficits, primarily in naming (subtests 3, 17, 18, and 25) and spelling (25–26), as well as in working memory (15–16).

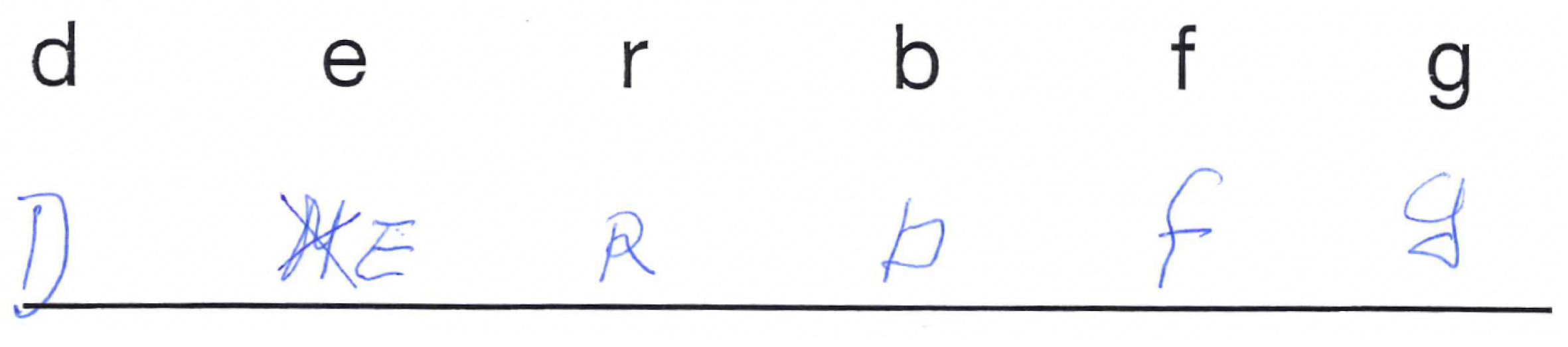

PPA4, on the other hand, exhibited a similar profile but with spared working memory, although his digit span score fell at the lowest end of the normal range, and he showed slightly worse performance on visual recognition memory and gesture object use. Lastly, PPA1 achieved the lowest scoring on the oral object naming subtest among the four participants. His performance also revealed problems in written production and spelling (26–27), as well as in nonlinguistic cognitive abilities, such as those assessed by the semantic subtests (2 and 4). His score on the copying task was very low, though this was due to his failure to follow instructions to copy the words in capital letters throughout the test (see an example in

Figure A2 in

Appendix B.2).

3.2. General Cognition

The CAT screens for cognitive deficits (subtests 1–6 and 15–16), which can provide information about factors that may influence language performance, as well as the course and symptom profile of the disease. As already mentioned, all the participants performed below the cutoff in the arithmetic and verbal fluency tasks, though the latter will be examined along with the naming subtests. Additionally, three out of the four participants exhibited difficulties on the gesture object use subtest, which screens for limb apraxia.

Furthermore, two participants scored below the threshold in the subtest that assesses semantic knowledge; notably, all errors—regardless of overall score—involved the selection of depictions of semantically related objects. The three participants who made errors on the semantic memory task performed below the cutoff on the recognition memory subtest, which required recalling the same items presented in the former task. This subtest allows for assessment of visual short-term recognition memory, whereas subtests 15 and 16 assess verbal short-term memory. In the digit span subtest, two participants performed above the cutoff, although at the lower end of the normal range, and two fell below the threshold. These two participants also scored below the normal range in the word span task, indicating working memory deficits, while the other two performed at ceiling.

3.3. Comprehension

Comprehension was the domain in which all participants made errors (see

Figure A1a in

Appendix A.2). PPA2 made the greatest number of errors across comprehension subtests, including near-floor performance on the sentence comprehension task, indicating a severe deficit. The other three participants’ errors in the word comprehension subtest involved both phonological and semantic distractors. With respect to sentence comprehension, their errors involved semantically reversible sentences (

Figure A1b): canonical sentences with two arguments or with prepositions, and non-canonical structures, such as passives and dislocations. Most errors (21 out of 24) consisted of the selection of the image depicting role reversal (e.g., PPA1 pointed to the image showing a glass placed on top of a plate when he heard the sentence

El got és sota el plat. ‘The glass is under the dish.’). Of these three participants, PPA1 shows the most severe deficit in sentence comprehension.

3.4. Word Production

The oral production of words was assessed across modalities, particularly naming and repetition. All participants except PPA2 performed at ceiling or near-ceiling levels on repetition subtests. For instance, only one participant, PPA4, made a single error, producing the word gust ‘taste’ instead of the nonword guts. PPA2, on the other hand, made errors across all word types. In most cases, he produced phonologically similar words, for example, he substituted the derivational morpheme in actualitat ‘current events’ with another morpheme autualitzar (actualitzar, ‘to update’).

All pwPPA scored below the cutoff threshold in naming subtests, with most errors consisting of no responses (22 out of 40 errors; see

Table A2 in

Appendix A.2) and at least one response in Spanish. PPA1 produced a majority of semantic errors, such as circumlocutions or semantic paraphasias. In contrast, PPA2 was the only participant who also produced perseverations. PPA3 did not respond initially, but when asked, she was able to describe the images using circumlocutions; for example, she used the expression “a house for working” for

factory. Finally, PPA4 presented the least severe deficit, and the few errors he made involved both semantic and phonetic paraphasias. Notably, all participants also made more mistakes with low-frequency nouns than with high-frequency ones (30 versus 7 errors, respectively). Similarly, they also tended to have more difficulty naming words with three or four syllables (22 errors) than shorter ones (15 errors), although the difference was less pronounced.

In the verbal fluency subtests, most pwPPA showed better performance on the semantic criterion than on the phonological one (

Table 2). Besides the number of appropriate nouns in Catalan that they produced per minute, the number and type of errors were also taken into account (see also

Table A2). PPA2, who produced the fewest words, made no mistakes, while PPA1 repeated one correct item in the semantic task. PPA4 made various errors, including circumlocutions in the semantic criterion and category errors (animals) in the phonological task. PPA3 produced inappropriate words only in the phonological task, namely two words in Spanish and one proper name.

3.5. Reading and Spelling

The CAT includes several tasks to assess reading skills across different word types. Additionally, spelling abilities are evaluated through various modalities, including letter and word copying, naming, writing to dictation, and describing an image. Importantly, all participants responded at least partially in one or more written subtests in Spanish (see

Appendix B.2 for examples) and one of them, PPA4, completed subtests 25 and 26 from the Spanish version of the CAT [

33], as per his request. Catalan orthography is more transparent than English but less so than Spanish, with frequent correspondence between spelling and sound. For this reason, the Catalan and Spanish versions of the CAT do not categorize items in terms of regularity [

17,

33], especially in reading subtests, which are consequently less sensitive to certain deficits. Catalan partially does so for writing subtests, though irregular words involve semi-transparent orthography in some dialects, as illustrated by errors like

restauran for

restaurant below. Nevertheless, as previous studies have argued [

38], a careful analysis of error types can reveal patterns of response that are informative about the nature of the deficit and relevant for diagnostic purposes of certain PPA variant types.

PPA1 correctly read and wrote pseudowords throughout the tasks. He produced very few reading errors; for instance, the only two mistakes involved similar words (e.g., Eixample (a neighborhood in Barcelona) instead of exemple ‘example’). However, he experienced more difficulties with spelling, including phonological errors, such as omitting letters that are not pronounced (e.g., restauran instead of restaurant in the copying subtest). In addition, he also had problems writing consonant clusters such as bl/br and the letter ñ in Spanish. Interestingly, he responded in Spanish only in the dictation and written description subtests.

In contrast, PPA2 showed significantly more severe deficits in production, as evidenced by automatisms, such as verbal perseveration, and anomia (see

Figure A3 in

Appendix B.2). While his reading abilities were spared, his writing errors in the naming and dictation subtests included phonologically similar words and nonwords (e.g.,

foc ‘fire’ instead of

pot ‘jar’ and

man instead of

mà ‘hand’). Interestingly, in the dictation subtest, he was unable to spell the pseudoword and made phonologically based errors with irregular words written as pronounced (e.g.,

impansable instead of

impensable).

PPA3 and PPA4 showed a similar pattern of spelling errors, all of which shared phonological similarity with the target. The errors involved all types of words: pseudowords (e.g., pur instead of plurc), irregular words (e.g., ada instead of hada (Spanish) ‘fairy’), regular words (e.g., abica instead of abeja (Spanish) ‘bee’), and even complex words (iomoda for incomodidad (Spanish) ‘discomfort’). Regarding the reading tasks, the few errors that these two participants made were also phonologically related to the target.

3.6. Description Tasks

Speech analysis is central for assessment and diagnosis of PPA, as discussed in Ossewaard et al. [

39] and references therein. The CAT-CAT includes a closed-class scoring system that allows for content and form variables to be evaluated separately (see

Appendix A.3 for raw scores and further details). As in other subtests, PPA2 was the participant with the lowest scores, all of which fell below the cutoff. The other participants showed more selective impairments (

Table A3). With regard to content variables in the oral description, they all exhibited low informativeness, producing only 0% to 66.7% of the relevant content units, but PPA1 produced a lower proportion of relevant nouns than verbs, while PPA3 showed the opposite pattern. Interestingly, productivity did not correspond to discourse efficiency, as the number of nouns and verbs produced did not translate into a greater number of relevant nouns and verbs (see

Table A4); for example, PPA4 produced 20 verbs, of which only 2 were relevant, whereas PPA1 produced 6 nouns, 4 of which were relevant.

In addition, the error analysis revealed distinct profiles across participants (see samples in

Appendix B.1). PPA1 exhibited predominantly anomic errors, with frequent use of filler words and circumlocutions. For instance, the most produced word by this participant was the non-specific deictic expression

aquí ‘here’ (11 occurrences). By contrast, PPA2 produced more effortful, shorter and less complex sentences. PPA3, on the other hand, demonstrated greater verbosity, and although she was the most fluent, her description was less coherent and sometimes difficult to follow. She was also the participant that switched to Spanish most frequently. Finally, PPA4 exhibited anomia as well, but his errors were mainly phonetic paraphasias.

As for form variables, they all scored below the cutoff on fluency, with the exception of PPA3. In fact, we measured the duration of both speech and pauses (silent and filled) to assess whether these quantitative measures (

Figure 2; see also

Table A5) aligned with the CAT-CAT scoring outcomes (

Table 2). The results showed alignment: for example, PPA1 and PPA3 both produced longer speech (means of 1.52 s and 2.03 s, respectively) than pause durations (means of 1.22 s and 1.03 s, respectively). However, this contrast was less pronounced in PPA1, whose shorter speech segments reflected more frequent alternation between brief utterances (37) and short pauses (22), hence, less fluency. In contrast, PPA2 and PPA4 produced longer pauses (means of 6.2 s and 2.58 s, respectively) than speech durations (means of 1.79 s and 1.51 s, respectively). In particular, PPA2’s pauses were very long and frequent (12 utterances, 8 pauses), which significantly affected his level of fluency. PPA4’s pauses were more consistent and slightly exceeded speech durations, indicating a more balanced speaking and pausing pattern (36 utterances, 29 pauses), but still reduced fluency.

The four participants performed worse on the written description task than on the oral one, in both content and form variables, with a greater decline observed in the latter (

Table A3), mainly due to less complex structures. PPA2 was also the participant who showed more severe impairments, as his written production included repeated content suggestive of perseveration (

Figure A3b in

Appendix B.2). The other participants produced a low number of relevant content units, although they showed different patterns of impairment: PPA3 and PPA4 named a greater number of relevant objects and actions than PPA1. Interestingly, all participants responded in Spanish, except for PPA4, who wrote the first sentence in Catalan (

Figure A4). Since the written descriptions were considerably shorter than the oral ones, the participants made fewer mistakes. Most of them involved word spelling errors, such as letter omissions and substitutions, similar to the ones previously described.

4. Discussion

The four participants studied were diagnosed with PPA based on clinical and neuroimaging criteria, and two of them, PPA2 and PPA4, were classified as nonfluent and logopenic variants, respectively. However, their language abilities had only been assessed informally or through general cognition screening tools, and primarily in their second language. We evaluated their linguistic abilities with the Comprehensive Aphasia Test in Catalan, their dominant language, to assess whether it could detect specific linguistic deficits and reveal distinct impairment profiles, despite not yet being specifically standardized for PPA. This section discusses the results in relation to the potential use of the CAT-CAT, and considers the study’s limitations and directions for future research.

4.1. Common Patterns

As expected, the results showed considerable intersubject variability among the participants, reflecting the characteristic heterogeneity of the syndrome [

4,

40], and particularly with respect to disease stage at assessment, as well as anatomical and etiological differences within the sample. However, they all shared certain features. For instance, the fact that all participants showed deficits in object naming and verbal fluency is consistent with the clinicians’ descriptions in their medical reports and with the literature, according to which anomia is the core deficit in PPA, present across all variants and among the earliest symptoms [

32]. Moreover, they performed poorly on the subtests assessing spelling, as documented across all variants in previous literature [

41,

42], as well as in word and sentence comprehension, with varying levels of severity. Notably, errors occurred across both canonical and non-canonical structures, a pattern that rules out the possibility of agrammatism as the primary source of the deficit. Finally, all participants exhibited impairments in oral descriptions, which will be examined individually in the following section.

One of the advantages of the CAT is that it includes a nonlinguistic cognitive screen, which revealed that the participants had impairments in domains beyond language. Given the progressive nature of the syndrome, examining non-linguistic cognitive abilities is particularly relevant in pwPPA, especially since our participants were assessed at a mean of 38.5 months post-onset. In fact, all participants showed deficits in calculation, and three exhibited impairments in praxis. Calculation deficits have been reported in pwPPA and Alzheimer’s disease, especially when there is involvement of the inferior parietal lobe [

43], as is the case for participants PPA2 and PPA4, and suspected in PPA1 and PPA3 based on clinical and biomarker findings. Similarly, apraxia can co-occur with PPA and does not exclude its diagnosis [

5]. In any case, the CAT includes a subtest that screens for limb praxis, which can interfere with gesture-based rather than oral communication. Despite these shared features, individual profiles revealed marked differences across domains and in degrees of severity.

4.2. Individual Profiles and Variant Type

Given the small sample and the aim to evaluate the clinical utility of the CAT-CAT for diagnosis and guiding intervention planning, we analyze the individual participant profiles and discuss their alignment with the three established PPA variants.

4.2.1. PPA1

Participant PPA1, although diagnosed with an unclassified type of PPA, exhibited a pattern compatible with the semantic variant. On one hand, he showed significant deficits both in naming and description subtests, as well as in nonverbal semantic and recognition memory subtests. As a result, his word and sentence comprehension were compromised. His speech also presented characteristics of the semantic variant [

44], in particular, the production of a high number of non-specific words, as well as circumlocutions, which affected the informativeness of the discourse despite being the participant who produced the highest number of words (

Appendix A.3). By contrast, the form variables showed intact grammatical abilities and no motor-speech impairments were observed.

On the other hand, his other abilities, such as repetition, were relatively spared. Despite the transparency of Catalan and Spanish orthographies and, hence, the limitation this imposes in the diagnosis of dysgraphia [

45], his errors in the subtests assessing spelling revealed patterns that could be consistent with surface dysgraphia [

41]: his errors with irregular words were phonologically plausible, while he accurately wrote pseudowords. Yet, he also exhibited additional orthographic impairments with certain letters. Regarding his unimpaired reading skills, which rule out a surface dyslexia diagnosis, the results align with those reported in the literature for Spanish-speaking populations with svPPA [

46,

47]. These deficits, together with the neuroimaging findings of lesions in the left inferior temporal lobe and white matter changes in periventricular regions, support the diagnosis of semantic variant PPA.

4.2.2. PPA2

Participant PPA2 was diagnosed with nfvPPA on the basis of his speech difficulties, which were mostly described as disfluent and severely anomic. For instance, the participant performed poorly on naming subtests, and his speech was filled with frequent and long pauses that significantly affected its fluency. However, the CAT-CAT also revealed severe linguistic deficits across several domains, which are compatible with the extensive brain damage in language-related regions, especially the left inferior frontal and parietotemporal lobes, reported in his medical records. In particular, his comprehension and production abilities were severely compromised, and he also exhibited varying degrees of deficits across nonlinguistic and linguistic tasks, with the sole exception of reading and copying, where his performance was at ceiling. Notably, he presented difficulties that are more common in other variants; for example, his comprehension problems were not restricted to more complex syntactic structures, he made several semantic errors in the word comprehension subtests, and he presented semantic memory deficits.

These impairments suggest that, at the time of assessment, the participant presented a more severe and mixed type of PPA rather than the nonfluent variant. The fact that he was assessed more than four years after the onset of the first symptoms could explain the progression and broadening of his deficits. This is further supported by the clinician’s observation, months later, that the syndrome had progressed to mutism and that some behavioral signs had started to appear. However, the passive behavior and attention difficulties described in the records may be due to his overlooked language impairments, particularly in the comprehension domain. In fact, if attentional issues had been the primary cause of these difficulties, we would have expected more generalized performance issues throughout the tasks, with more inconsistent errors and difficulties in finishing the test. Yet, his errors, such as semantic and phonetic paraphasias, were more indicative of language processing deficits.

4.2.3. PPA3

Participant PPA3 was diagnosed with an unclassified form of PPA secondary to Alzheimer’s disease and presents with the mildest deficits among the participants. The pattern of impairment observed in the CAT-CAT is compatible with the logopenic variant, as she exhibits the core features, namely anomia and phonological short-memory deficits, which may in turn contribute to her relatively mild comprehension difficulties. Her phonologically based spelling impairments across all types of words are also compatible with this variant [

41]. In addition, her general cognitive abilities and certain linguistics skills are relatively spared, such as semantic memory or repetition. Moreover, neuroimaging findings of left hemisphere atrophy, along with the confirmed Alzheimer’s disease etiology, further support this classification [

48].

Finally, her oral description also showed some features that could be compatible with lvPPA, as described in previous literature [

49]; in particular, despite being fluent, she exhibited frequent false starts and filled pauses, with filled pauses accumulating a notable duration relative to silent pauses (

Table A5). In addition, she displayed greater verbosity and difficulty maintaining focus. For example, she finished her description with the sentence

Bueno, les flors aquestes. No sé t-t-t… (1.45, filled) Per això s’ha sortit a fora. (‘Well, these flowers. I don’t kno-kn-know… That’s why he/she/it went outside.’). Notably, no figure in the image is actually going outside. Moreover, she made some phonological errors, sometimes resulting in unintelligible sequences, while her grammatical abilities were spared.

4.2.4. PPA4

Participant PPA4 was diagnosed with lvPPA based on observed atrophy in the parietal lobes and naming deficits; however, his results on the CAT-CAT only partially fit the variant. He exhibited anomia, milder than that of the other participants in the naming subtests, but more obvious in the description task, where the pause placement in his speech suggested that his disfluency was related to lexical retrieval problems. These results are consistent with previous findings indicating that lvPPA can present with both fluent and non-fluent speech [

50]. Unlike PPA3, his oral description was more focused and less verbose, but he exhibited other characteristics consistent with lvPPA [

51], namely the aforementioned frequent pauses reflecting naming deficits and the fact that he expressed difficulty in carrying out the task several times (e.g.,

És massa liàs. ‘It’s too confusing.’). However, he made both phonological and semantic errors across different subtests, the latter being more common in svPPA.

In addition, he showed a broad pattern of phonological errors in spelling subtests and comprehension deficits similar to those described for PPA3, as expected in lvPPA. However, his performance on verbal short-term memory was above the cutoff threshold, despite his digit span being at the lower end and his visual recognition memory falling below the cutoff. Short-term memory deficits are one of the classification criteria for lvPPA and are often argued to underlie its comprehension deficits. In addition, he showed mild deficits in semantic memory, also typical of svPPA. The profile at the time of assessment may therefore represent a case with features that do not clearly align with the established classifications. This ambiguity could be attributed to a more advanced stage of the disease, which often manifests as overlapping variants [

52].

4.3. Clinical Utility of the CAT-CAT and Limitations

The main goal of this study was to explore whether the CAT-CAT could be used to assess and diagnose pwPPA in Catalan-speaking individuals. The results discussed above show that the test detected impairments across several linguistic and nonlinguistic subtests in all participants. The observed deficits not only aligned with the core features of PPA, such as anomia, but were also sensitive to distinct impairment and severity profiles, some of which potentially compatible with classic variant types, as defined in Gorno-Tempini et al. [

5]. More importantly, the results were generally compatible with the participants’ medical records, which described the results of neuroimaging studies, clinical observations, and patients’ complaints. Interestingly, the CAT’s brief general cognition screening test also revealed cognitive deterioration, complementing the detailed language assessment.

Moreover, our assessment showed great sensitivity, as it captured deficits that were overlooked or misattributed in clinical explorations. For example, despite PPA4 reporting difficulties with comprehension during the initial consultation, the medical records consistently attributed these issues to auditory problems rather than true language comprehension deficits. This perspective was maintained throughout follow-up visits before our assessment. However, the CAT-CAT rules out the possibility of purely auditory deficits: on one hand, he performed at ceiling on repetition subtests that rely heavily on auditory processing, and on the other hand, he exhibited clear difficulties in both written word and sentence comprehension. Likewise, the patient showed difficulties in spelling, contrary to the medical records, which stated there were no alterations in writing. It is important to note that these writing impairments cannot be attributed to differences in L1 and L2, as the patient’s spelling was assessed using the Spanish version of the CAT.

Similarly, the language difficulties reported by PPA2 and his relatives were initially attributed to stress-related problems, resulting in a four-year delay in PPA diagnosis. As with the previous patient, the medical records mentioned social isolation and decreased attention, but not comprehension problems, even months after our assessment. However, the results of this study showed that PPA2 presented a severe deficit in comprehension cannot be explained by attentional deficits, as discussed above. The fact that the CAT-CAT detected distinct linguistic impairments, including those overlooked in clinical explorations, suggests that it could be a valuable tool to assess and diagnose Catalan-speaking pwPPA. This further emphasizes the need of comprehensive language assessment for early and accurate diagnosis.

In addition, the variability of symptoms and the difficulty in classifying some of the patients highlight the critical need for detailed linguistic profiling rather than reliance on general cognition screenings or informal tests alone. This is partly due to the heterogeneous nature of the syndrome, but it can be exacerbated by the lack of standardized tools available for minority-language speakers. Our participants’ histories (e.g., PPA2’s four-year diagnostic delay and severity, the presence of general cognitive deficits…) exemplify the impact of current gaps in the assessment of Catalan-speaking individuals. In fact, one novel aspect of this study is its focus on the dominant language of bilingual speakers, whereas previous bilingual research has examined PPA mainly in relation to or focused solely on the majority language (e.g., Spanish in [

53]).

4.4. Bilingualism in Minority Language Speakers

The results revealed some of the challenges often encountered when examining bilingual speakers of minority languages, for whom language-mixing and code-switching behavior is very common, even in individuals without language disorders. For instance, the normative study with 110 control participants revealed interferences from L2 (Spanish) in the verbal fluency subtests and in the oral description, mostly at the lexical level, but not in other oral tasks [

17]. However, these interferences were not significant: for example, in the oral naming subtest, only 5 out of the 2640 responses were in Spanish, and in the naming subtests, 55 out of a total of 2886 responses. Hence, a high proportion of interferences from L2 in oral subtests should be considered non-normative.

In this study, all pwPPA switched to Spanish in written subtests and occasionally responded in Spanish in naming tasks. Based on the normative data, the pwPPA’s responses in Spanish during the naming subtests and PPA2’s interferences in the writing-to-dictation subtest are atypical and could be considered pathological. Although several studies have observed language-switching behavior as a communication strategy in individuals with language disorders [

54], the patterns of response observed in the pwPPA suggest otherwise. For example, in the object naming subtest, the most frequent errors were non-responses, which indicates that the strategy of switching to the second language was either not available or not efficient.

However, also taking the normative data into account, responses in Spanish in the written subtests should be interpreted differently to avoid underestimating preserved language abilities. As noted, their code-switching behavior in written tasks is probably due to their lack of formal education in Catalan, and it was also observed in participants without disorders of the same age who tended to oversimplify and shorten their descriptions to avoid writing in Catalan. This suggests that pwPPA could have been switching to their L2 in written description as a communication strategy.

While there are no previous studies on Catalan-dominant bilinguals with PPA, our findings align with Gómez-Ruiz et al. [

55] who reported that Catalan-dominant bilinguals with Alzheimer’s disease performed better in their L2 (Spanish) on written subtests. Similarly, the review of studies on multilinguals with PPA and dementia conducted by Malcolm et al. [

9] reported that, while L1 was usually better preserved than L2, dominance did not always explain performance. We suggest that dominance interacts with sociocultural factors related to the unbalanced status of minoritized versus majority languages, and that individuals may show dominance in different languages depending on the domain or context. It is important to note that the observed preference for Spanish in written tasks in this study does not indicate that L2 is inherently better preserved, as suggested by previous studies [

55], but rather reflects limited opportunities to develop L1 writing skills.

This is consistent with the hypothesis postulated by Green and Abutalebi [

56], according to which language control processes in bilinguals adapt to the demands of different contexts. In line with this model, the preference for Spanish in written tasks among the pwPPA may reflect adaptive control rather than a deficit, as participants select the language that maximizes communicative efficiency in a given context. For the pwPPA in this study, Spanish was the most used language for writing, which would explain the interferences from Spanish in the written subtests (e.g., PPA2’s responses in the writing-to-dictation subtest were in Spanish). However, one participant chose to complete the written tests in Spanish because he was aware of his difficulties in Catalan, which was unrelated to cognitive control processes. Further research with a larger sample size is needed to clarify this issue.

These findings further highlight the importance of using standardized tests for the assessment of minority languages to obtain an accurate linguistic profile, as the bilingual status of the participant could affect the interpretation of assessment results. In addition, they also emphasize the need for flexible and tailored assessments in minority-language populations; for example, conducting oral subtests in Catalan and written subtests in Spanish, as in this study. The advantage of the CAT is that its multilingual availability allows flexible administration across languages, such as Catalan and Spanish. This enables clinicians to customize the assessment to the patient’s dominant language in each domain, especially in time-limited clinical settings, thereby maximizing diagnostic accuracy and facilitating the design of more effective interventions.

5. Conclusions

This study evaluated the Catalan version of the Comprehension Aphasia Test for detecting and characterizing PPA in Catalan-dominant bilingual individuals. Our findings showed that the test was sensitive to the deficits presented by the four participants: it detected core linguistic impairments, such as anomia, and revealed distinct severity profiles consistent with PPA variant types. Moreover, it captured deficits that were not identified by routine clinical observation or informal assessment. Despite its limitations, this study emphasizes the need for language assessment tools to assist in the clinical diagnosis of primary progressive aphasia, whose initial symptoms often go unnoticed otherwise.

As the first study to systematically characterize PPA in Catalan, this work fills a critical gap in neurodegenerative language research and provides a foundation for more equitable clinical practice. While no current treatments prevent PPA progression, early diagnosis enabled by tools like the CAT-CAT facilitates interventions that can improve communication and quality of life for patients and their relatives. Recent studies have shown that interventions can be effective for pwPPA in early stages (e.g., [

57]). However, without an accurate assessment, interventions cannot be targeted effectively. For Catalan-speaking PPA patients, the CAT-CAT represents a crucial first step toward equitable care.

Nonetheless, this preliminary study has some limitations, including a small sample size, which future research should address, as our findings are exploratory and cannot be generalized beyond the current sample. This study was intended to assess the feasibility of administering the CAT-CAT in Catalan-speaking PPA patients and to generate initial descriptive data. These preliminary results will inform the design of larger-scale studies aimed at validating the tool’s clinical utility, including its ability to diagnose PPA, distinguish its variants, and evaluate potential therapy outcomes following L1-language interventions.