Intracranial Aneurysms Treated with a Novel Coated Low-Profile Flow Diverter (p48 HPC)—A Single-Center Experience and an Illustrative Case Series

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Device Description

2.2. Patient Characteristics and Endovascular Procedures

3. Results

3.1. Patients and Aneurysms

3.2. Endovascular Procedures

3.3. Early Angiographic Results and Follow-Up

3.4. Periprocedural Complications

3.5. Illustrative Cases

3.5.1. Unruptured Aneurysms

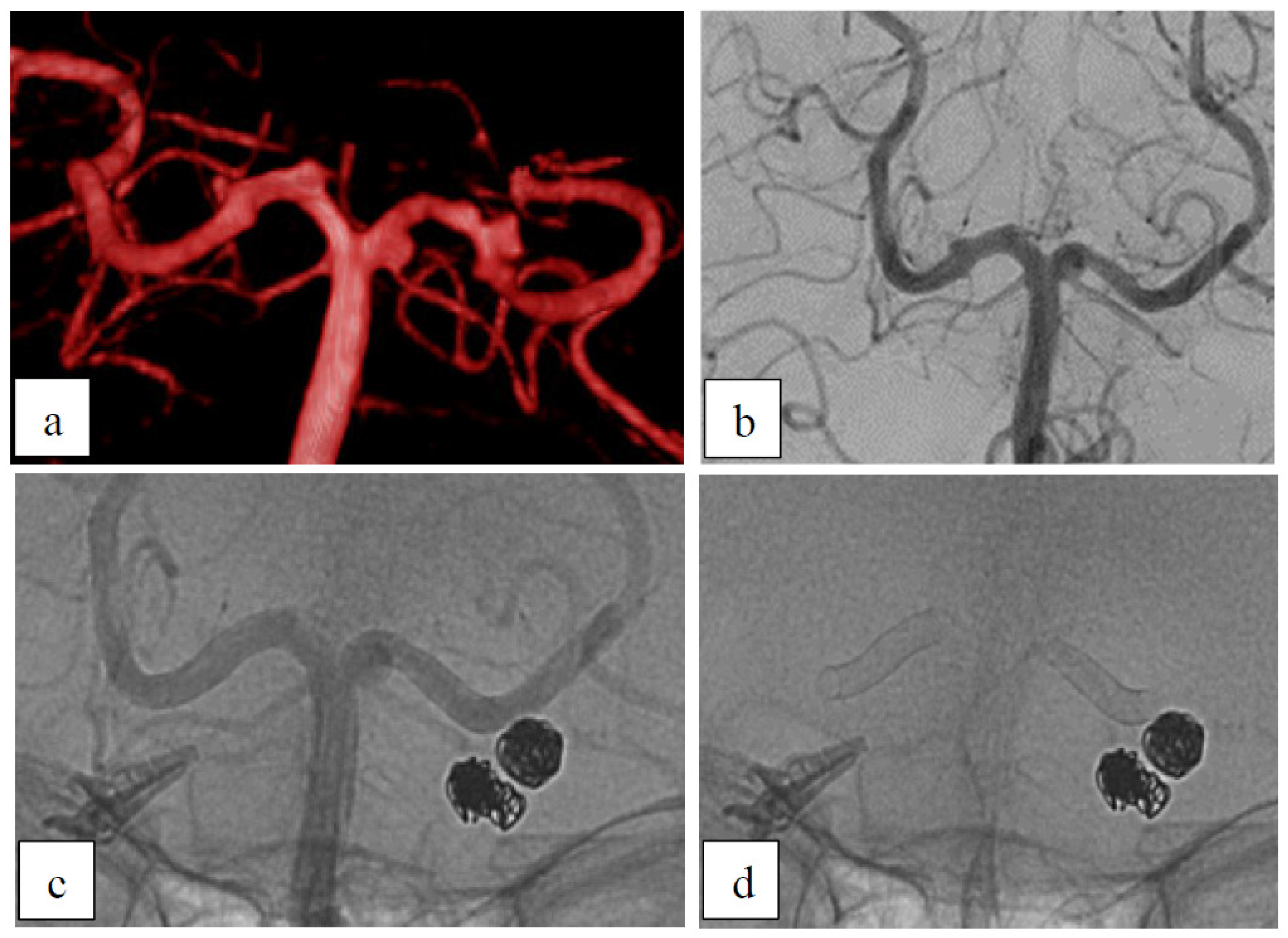

Case 1: Dysplastic Aneurysms

Case 2: Dysplastic Aneurysm with Incorporated Branch

Case 3: Recurrent Aneurysm After Clipping

3.5.2. Ruptured Aneurysms

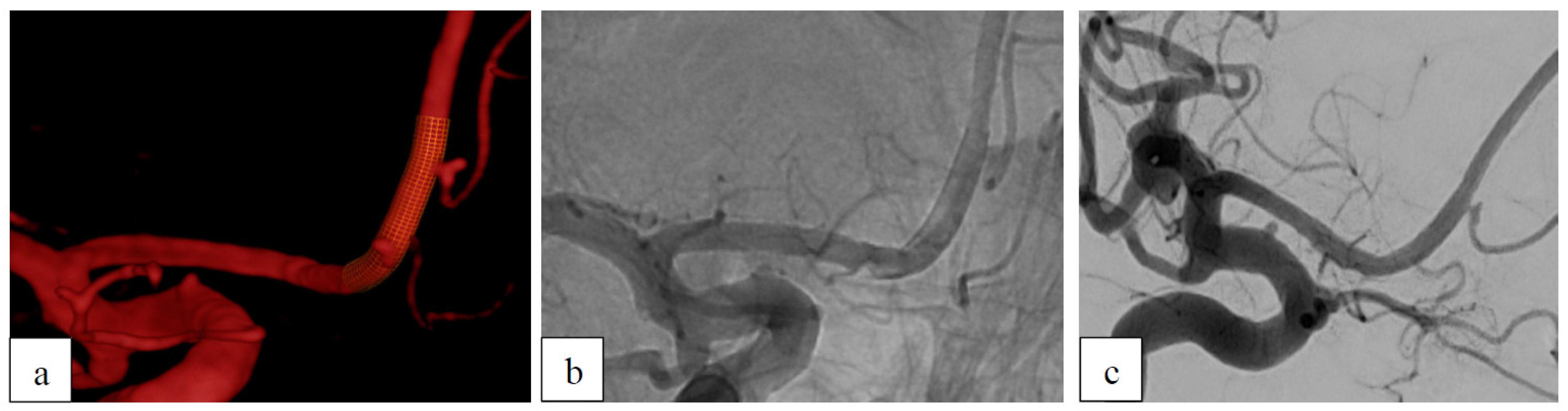

Case 4: Dissecting Aneurysm

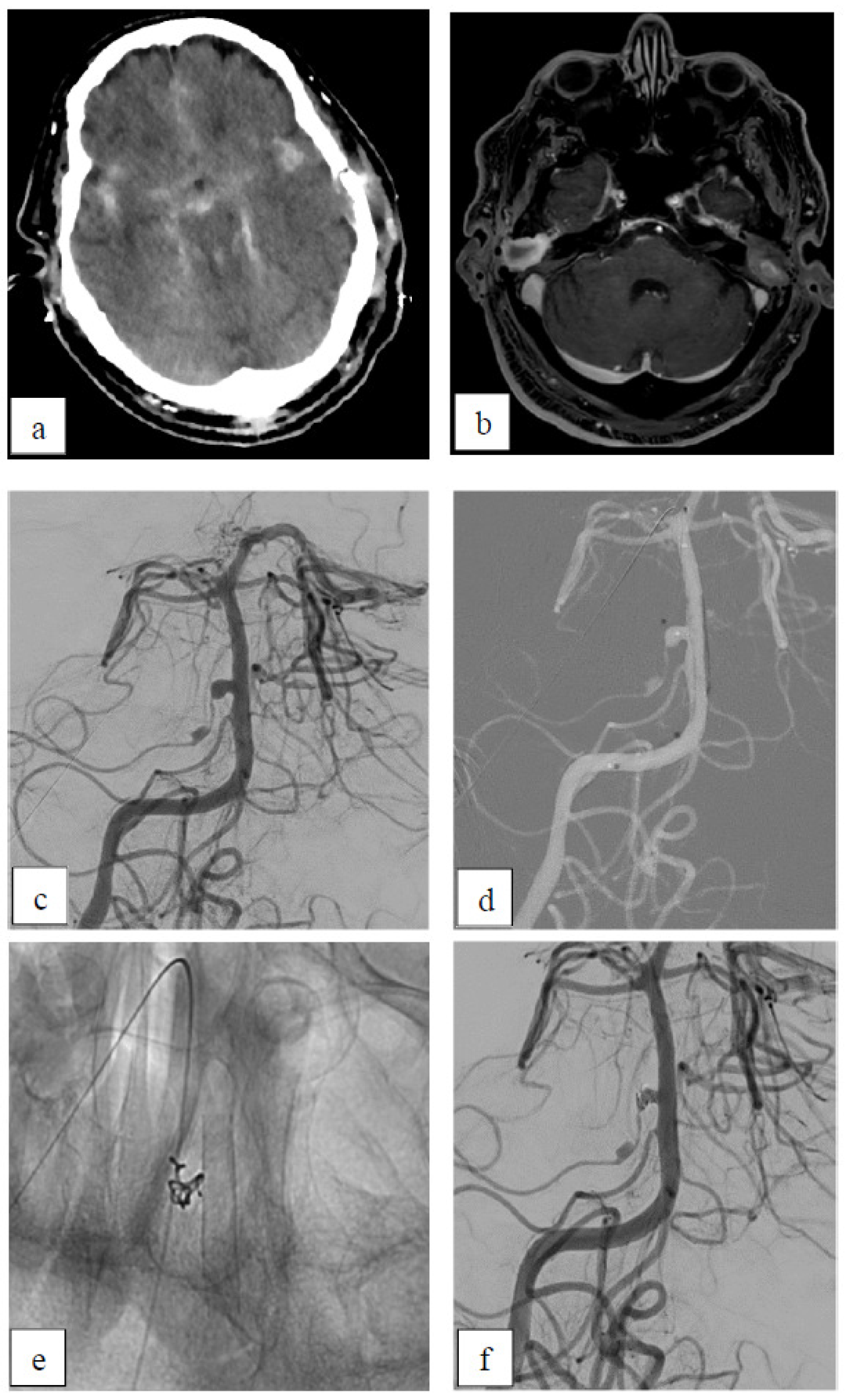

Case 5: Inflammatory Aneurysm

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schob, S.; Hoffmann, K.T.; Richter, C.; Bhogal, P.; Kohlert, K.; Planitzer, U.; Ziganshyna, S.; Lindner, D.; Scherlach, C.; Nestler, U.; et al. Flow diversion beyond the circle of Willis: Endovascular aneurysm treatment in peripheral cerebral arteries employing a novel low-profile flow diverting stent. J. Neurointerv. Surg. 2019, 11, 1227–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gawlitza, M.; Januel, A.C.; Tall, P.; Bonneville, F.; Cognard, C. Flow diversion treatment of complex bifurcation aneurysms beyond the circle of Willis: A single-center series with special emphasis on covered cortical branches and perforating arteries. J. Neurointerv. Surg. 2016, 8, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augsburger, L.; Farhat, M.; Reymond, P.; Fonck, E.; Kulcsar, Z.; Stergiopulos, N.; Rufenacht, D.A. Effect of flow diverter porosity on intraaneurysmal blood flow. Klin. Neuroradiol. 2009, 19, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieber, B.B.; Stancampiano, A.P.; Wakhloo, A.K. Alteration of hemodynamics in aneurysm models by stenting: Influence of stent porosity. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 1997, 25, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhogal, P.; Lenz-Habijan, T.; Bannewitz, C.; Hannes, R.; Monstadt, H.; Brodde, M.; Kehrel, B.; Henkes, H. Thrombogenicity of the p48 and anti-thrombogenic p48 hydrophilic polymer coating low-profile flow diverters in an in vitro human thrombin generation model. Interv. Neuroradiol. 2020, 26, 488–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhogal, P.; Bleise, C.; Chudyk, J.; Lylyk, I.; Perez, N.; Henkes, H.; Lylyk, P. The p48_HPC antithrombogenic flow diverter: Initial human experience using single antiplatelet therapy. J. Int. Med. Res. 2020, 48, 300060519879580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Kelly, C.J.; Krings, T.; Fiorella, D.; Marotta, T.R. A novel grading scale for the angiographic assessment of intracranial aneurysms treated using flow diverting stents. Interv. Neuroradiol. 2010, 16, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiehler, J.; Ortega-Gutierrez, S.; Anagnostakou, V.; Cortese, J.; Cekirge, H.S.; Fiorella, D.; Hanel, R.; Kulcsar, Z.; Lamin, S.; Liu, J.; et al. Evaluation of flow diverters for cerebral aneurysm therapy: Recommendations for imaging analyses in clinical studies, endorsed by ESMINT, ESNR, OCIN, SILAN, SNIS, and WFITN. J. Neurointerv. Surg. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djulejic, V.; Marinkovic, S.; Milic, V.; Georgievski, B.; Rasic, M.; Aksic, M.; Puskas, L. Common features of the cerebral perforating arteries and their clinical significance. Acta Neurochir. 2015, 157, 743–754, discussion 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Su, M.; Yin, Y.L.; Li, M.H. Complications associated with the use of flow-diverting devices for cerebral aneurysms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurg. Focus 2017, 42, E17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Texakalidis, P.; Bekelis, K.; Atallah, E.; Tjoumakaris, S.; Rosenwasser, R.H.; Jabbour, P. Flow diversion with the pipeline embolization device for patients with intracranial aneurysms and antiplatelet therapy: A systematic literature review. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2017, 161, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Castro-Afonso, L.H.; Nakiri, G.S.; Abud, T.G.; Monsignore, L.M.; de Freitas, R.K.; Abud, D.G. Aspirin monotherapy in the treatment of distal intracranial aneurysms with a surface modified flow diverter: A pilot study. J. Neurointerv. Surg. 2021, 13, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Perez, M.; Hellstern, V.; AlMatter, M.; Wendl, C.; Bazner, H.; Ganslandt, O.; Henkes, H. The p48 Flow Modulation Device with Hydrophilic Polymer Coating (HPC) for the Treatment of Acutely Ruptured Aneurysms: Early Clinical Experience Using Single Antiplatelet Therapy. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2020, 43, 740–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro-Afonso, L.H.; Nakiri, G.S.; Abud, T.G.; Monsignore, L.M.; Freitas, R.K.; de Oliveira, R.S.; Colli, B.O.; Dos Santos, A.C.; Abud, D.G. Treatment of distal unruptured intracranial aneurysms using a surface-modified flow diverter under prasugrel monotherapy: A pilot safety trial. J. Neurointerv. Surg. 2021, 13, 647–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goertz, L.; Hohenstatt, S.; Vollherbst, D.F.; Weyland, C.S.; Nikoubashman, O.; Gronemann, C.; Pflaeging, M.; Siebert, E.; Bohner, G.; Zopfs, D.; et al. Safety and efficacy of coated flow diverters in the treatment of cerebral aneurysms during single antiplatelet therapy: A multicenter study. Interv. Neuroradiol. 2024, 30, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellstern, V.; Aguilar Perez, M.; Henkes, E.; Donauer, E.; Wendl, C.; Bazner, H.; Ganslandt, O.; Henkes, H. Use of a p64 MW Flow Diverter with Hydrophilic Polymer Coating (HPC) and Prasugrel Single Antiplatelet Therapy for the Treatment of Unruptured Anterior Circulation Aneurysms: Safety Data and Short-term Occlusion Rates. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2022, 45, 1364–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellstern, V.; Brenner, N.; Cimpoca, A.; Albina Palmarola, P.; Henkes, E.; Wendl, C.; Bazner, H.; Ganslandt, O.; Henkes, H. Flow diversion for unruptured MCA bifurcation aneurysms: Comparison of p64 classic, p64 MW HPC, and p48 MW HPC flow diverter stents. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1415861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Madjidyar, J.; Schubert, T.; Thurner, P.; Barnaure, I.; Kulcsar, Z. Single antiplatelet regimen in flow diverter treatment of cerebral aneurysms: The drug matters. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Interv. Neuroradiol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhogal, P.; Petrov, A.; Rentsenkhu, G.; Nota, B.; Ganzorig, E.; Regzengombo, B.; Jagusch, S.; Henkes, E.; Henkes, H. Early clinical experience with the p48MW HPC and p64MW HPC flow diverters in the anterior circulation aneurysm using single anti-platelet treatment. Interv. Neuroradiol. 2022, 28, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzzardi, G.; Galbiati, A.; Stanca, C.; Del Sette, B.; Paladini, A.; Cossandi, C.; Carriero, A. Flow diverter stents with hydrophilic polymer coating for the treatment of acutely ruptured aneurysms using single antiplatelet therapy: Preliminary experience. Interv. Neuroradiol. 2020, 26, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobsien, D.; Clajus, C.; Behme, D.; Ernst, M.; Riedel, C.H.; Abu-Fares, O.; Gotz, F.G.; Fiorella, D.; Klisch, J. Aneurysm Treatment in Acute SAH with Hydrophilic-Coated Flow Diverters under Single-Antiplatelet Therapy: A 3-Center Experience. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2021, 42, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierot, L.; Soize, S.; Cappucci, M.; Manceau, P.F.; Riva, R.; Eker, O.F. Surface-modified flow diverter p48-MW-HPC: Preliminary clinical experience in 28 patients treated in two centers. J. Neuroradiol. 2021, 48, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schob, S.; Klaver, M.; Richter, C.; Scherlach, C.; Maybaum, J.; Mucha, S.; Schungel, M.S.; Hoffmann, K.T.; Quaeschling, U. Single-Center Experience with the Bare p48MW Low-Profile Flow Diverter and Its Hydrophilically Covered Version for Treatment of Bifurcation Aneurysms in Distal Segments of the Anterior and Posterior Circulation. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlMatter, M.; Henkes, E.; Sirakov, A.; Aguilar Perez, M.; Hellstern, V.; Serna Candel, C.; Ganslandt, O.; Henkes, H. The p48 MW flow modulation device for treatment of unruptured, saccular intracranial aneurysms: A single center experience from 77 consecutive aneurysms. CVIR Endovasc. 2020, 3, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becske, T.; Brinjikji, W.; Potts, M.B.; Kallmes, D.F.; Shapiro, M.; Moran, C.J.; Levy, E.I.; McDougall, C.G.; Szikora, I.; Lanzino, G.; et al. Long-Term Clinical and Angiographic Outcomes Following Pipeline Embolization Device Treatment of Complex Internal Carotid Artery Aneurysms: Five-Year Results of the Pipeline for Uncoilable or Failed Aneurysms Trial. Neurosurgery 2017, 80, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becske, T.; Kallmes, D.F.; Saatci, I.; McDougall, C.G.; Szikora, I.; Lanzino, G.; Moran, C.J.; Woo, H.H.; Lopes, D.K.; Berez, A.L.; et al. Pipeline for uncoilable or failed aneurysms: Results from a multicenter clinical trial. Radiology 2013, 267, 858–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, Y.H.; Choi, J.; Huh, C.W.; Kim, C.H.; Chang, C.H.; Kwon, S.C.; Kim, Y.W.; Sheen, S.H.; Park, S.Q.; Ko, J.K.; et al. Imaging follow-up strategy after endovascular treatment of Intracranial aneurysms: A literature review and guideline recommendations. J. Cerebrovasc. Endovasc. Neurosurg. 2024, 26, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soize, S.; Gawlitza, M.; Raoult, H.; Pierot, L. Imaging Follow-Up of Intracranial Aneurysms Treated by Endovascular Means: Why, When, and How? Stroke 2016, 47, 1407–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flood, T.; Bom, I.; Strittmatter, L.; Puri, A.; Hendricks, G.; Wakhloo, A.; Gounis, M. Quantitative analysis of high-resolution, contrast-enhanced, cone-beam CT for the detection of intracranial in-stent hyperplasia. J. Neurointerv. Surg. 2014, 7, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trivelato, F.P.; Salles Rezende, M.T.; Ulhoa, A.C.; Henrique de Castro-Afonso, L.; Nakiri, G.S.; Abud, D.G. Occlusion rates of intracranial aneurysms treated with the Pipeline embolization device: The role of branches arising from the sac. J. Neurosurg. 2018, 130, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popica, D.A.; Cortese, J.; Oliver, A.A.; Plaforet, V.; Molina Diaz, I.; Rodriguez-Erazu, F.; Ikka, L.; Mihalea, C.; Chalumeau, V.; Kallmes, D.F.; et al. Flow diverter braid deformation following treatment of cerebral aneurysms: Incidence, clinical relevance, and potential risk factors. J. Neurointerv. Surg. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega-Gutierrez, S.; Rodriguez-Calienes, A.; Vivanco-Suarez, J.; Cekirge, H.S.; Hanel, R.A.; Dibas, M.; Lamin, S.; Rice, H.; Saatci, I.; Fiorella, D.; et al. Braid stability after flow diverter treatment of intracranial aneurysms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurointerv. Surg. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age | Sex | Location | Laterality | Type | Ruptured | Previous Treatment | Antiplatelet Therapy | OKM After FDS | Last FU (Months) | OKM Last FU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | f | P1/2 (two aneurysms) | bilateral | dysplastic | no | no | ASA+ Clopidogrel | left: B2 right: B2 | left: 3 | left: D1 right: − |

| 55 | f | A2 (two aneurysms) | right | dysplastic | no | no | ASA+ Prasugrel | prox: B2 dist: A2 | prox: 6 dist: 6 | prox: D1 dist: B2 |

| 52 | m | AcomA | - | saccular | no | coiling | ASA+ Clopidogrel | - | 12 | D1 |

| 26 | f | V4 | left | dissecting | no | no | ASA+ Clopidogrel | D1 | 8 | D1 |

| 71 | f | AcomA | - | saccular | no | clipping+ coiling | ASA+ Clopidogrel | C2 | 6 | D1 |

| 70 | f | AcomA | - | saccular | no | clipping | ASA+ Clopidogrel | D1 | 7 | D1 * |

| 44 | f | AcomA | - | blister | yes | no | ASA+ Clopidogrel | D1 | 13 | D1 |

| 28 | f | P2/P3 | right | dissecting | yes | no | ASA+ Clopidogrel | A2 | 5 | D1 |

| 71 | f | SUCA BA | right | blister saccular | Yes (SAH) † | no | ASA+ Clopidogrel | SUCA:A2 BA: A3 | SUCA: 6 BA: 6 | SUCA:A2 BA: C2 |

| 48 | m | V4 | left | dissecting | yes | no | ASA+ Clopidogrel | A3 | 6 | D1 |

| 60 | f | V4 | left | dissecting | yes | no | ASA | A3 | - | - |

| 67 | m | AICA (2 aneurysms) | right | inflammatory | yes (SAH) | no | ASA | prox: B3 dist: A3 | - | - |

| 35 | f | terminal ICA | right | blister | yes | no | ASA+ Clopidogrel | D1 | - | - |

| 57 | m | V4 | right | dissecting | no | no | ASA+ Clopidogrel | A3 | - | - |

| Age | Sex | Location | Laterality | Type | Ruptured | Previous Treatment | Antiplatelet Therapy | OKM After FDS | Last FU (Months) | OKM Last FU | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 50 | f | P1/2 (two aneurysms) | bilateral | dysplastic | no | no | ASA+ Clopidogrel | left: B2 right: B2 | left: 3 | left: D1 right: − |

| 2 | 55 | f | A2 (two aneurysms) | right | dysplastic | no | no | ASA+ Prasugrel | prox: B2 dist: A2 | prox: 6 dist: 6 | prox: D1 dist: B2 |

| 3 | 70 | f | AcomA | - | saccular | no | clipping | ASA+ Clopidogrel | D1 | 7 | D1 * |

| 4 | 48 | m | V4 | left | dissecting | yes | no | ASA+ Clopidogrel | A3 | 6 | D1 |

| 5 | 67 | m | AICA (two aneurysms) | right | inflammatory | yes (SAH) | no | ASA | prox:B3 dist: A3 | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Krug, N.; Kirschke, J.S.; Maegerlein, C.; Kreiser, K.; Wostrack, M.; Meyer, B.; Albrecht, C.; Zimmer, C.; Boeckh-Behrens, T.; Sepp, D. Intracranial Aneurysms Treated with a Novel Coated Low-Profile Flow Diverter (p48 HPC)—A Single-Center Experience and an Illustrative Case Series. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15010042

Krug N, Kirschke JS, Maegerlein C, Kreiser K, Wostrack M, Meyer B, Albrecht C, Zimmer C, Boeckh-Behrens T, Sepp D. Intracranial Aneurysms Treated with a Novel Coated Low-Profile Flow Diverter (p48 HPC)—A Single-Center Experience and an Illustrative Case Series. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(1):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15010042

Chicago/Turabian StyleKrug, Nadja, Jan S. Kirschke, Christian Maegerlein, Kornelia Kreiser, Maria Wostrack, Bernhard Meyer, Carolin Albrecht, Claus Zimmer, Tobias Boeckh-Behrens, and Dominik Sepp. 2025. "Intracranial Aneurysms Treated with a Novel Coated Low-Profile Flow Diverter (p48 HPC)—A Single-Center Experience and an Illustrative Case Series" Brain Sciences 15, no. 1: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15010042

APA StyleKrug, N., Kirschke, J. S., Maegerlein, C., Kreiser, K., Wostrack, M., Meyer, B., Albrecht, C., Zimmer, C., Boeckh-Behrens, T., & Sepp, D. (2025). Intracranial Aneurysms Treated with a Novel Coated Low-Profile Flow Diverter (p48 HPC)—A Single-Center Experience and an Illustrative Case Series. Brain Sciences, 15(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15010042