Physiological Correlates of Hypnotizability: Hypnotic Behaviour and Prognostic Role in Medicine

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Evidence and Related Hypotheses

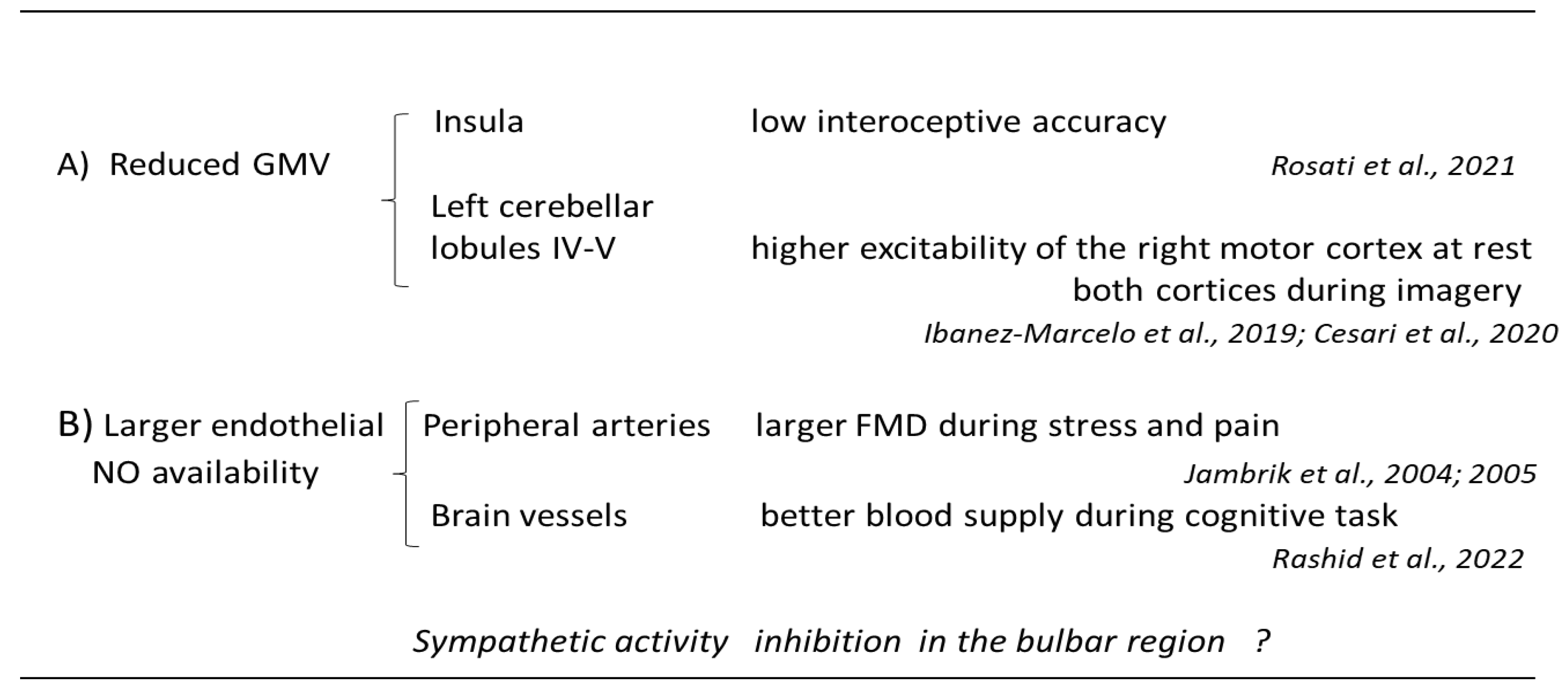

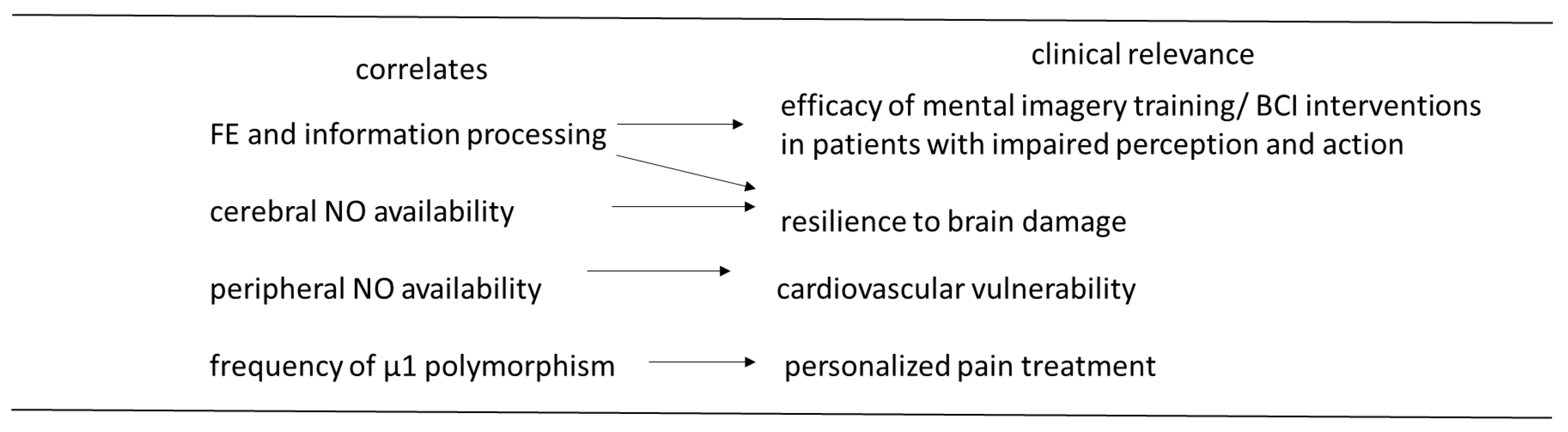

2.1. Cerebral Morpho-Functional and Vascular Correlates of Hypnotizability

2.2. Functional Equivalence between Real and Imagined Perception/Action

2.3. Motor Cortex Excitability

2.4. Attention, Pain Control and the Cerebellum

2.5. Interoception

2.6. Hypnotizability and Brain Injuries

2.7. Cardiovascular Control

2.8. Polymorphism of µ1 Receptors

3. Limitations and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Piccione, C.; Hilgard, E.R.; Zimbardo, P.G. On the degree of stability of measured hypnotizability over a 25-year period. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 56, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acunzo, D.J.; Terhune, D.B. A Critical Review of Standardized Measures of Hypnotic Suggestibility. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Hypn. 2021, 69, 50–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santarcangelo, E.L.; Cavallaro, E.; Mazzoleni, S.; Marano, E.; Ghelarducci, B.; Dario, P.; Micera, S.; Sebastiani, L. Kinematic strategies for lowering of upper limbs during suggestions of heaviness: A real-simulator design. Exp. Brain Res. 2005, 162, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carli, G.; Suman, A.L.; Biasi, G.; Marcolongo, R.; Santarcangelo, E.L. Paradoxical experience of hypnotic analgesia in low hypnotizable fibromyalgic patients. Arch. Ital. Biol. 2008, 146, 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Derbyshire, S.W.; Whalley, M.G.; Oakley, D.A. Fibromyalgia pain and its modulation by hypnotic and non-hypnotic suggestion: An fMRI analysis. Eur. J. Pain. 2009, 13, 542–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.P.; Lynn, S.J. Hypnotic responsiveness: Expectancy, attitudes, fantasy proneness, absorption, and gender. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Hypn. 2011, 59, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parris, B.A.; Dienes, Z. Hypnotic suggestibility predicts the magnitude of the imaginative word blindness suggestion effect in a non-hypnotic context. Conscious. Cogn. 2013, 22, 868–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ku, Y. Hypnotic and non-hypnotic suggestion to ignore pre-cues decreases space-valence congruency effects in highly hypnotizable individuals. Conscious. Cogn. 2018, 65, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santarcangelo, E.L.; Carli, G. Individual Traits and Pain Treatment: The Case of Hypnotizability. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 683045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.P.; Adachi, T.; Tomé-Pires, C.; Lee, J.; Osman, Z.J.; Miró, J. Mechanisms of hypnosis: Toward the development of a biopsychosocial model. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Hypn. 2015, 63, 34–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terhune, D.B.; Cardeña, E.; Lindgren, M. Dissociated control as a signature of typological variability in high hypnotic suggestibility. Conscious. Cogn. 2011, 20, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, M.; Lifshitz, M.; Raz, A. Brain correlates of hypnosis: A systematic review and meta-analytic exploration. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 81 Pt A, 75–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picerni, E.; Santarcangelo, E.L.; Laricchiuta, D.; Cutuli, D.; Petrosini, L.; Spalletta, G.; Piras, F. Cerebellar Structural Variations in Participants with Different Hypnotizability. Cerebellum 2019, 18, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibáñez-Marcelo, E.; Campioni, L.; Phinyomark, A.; Petri, G.; Santarcangelo, E.L. Topology highlights mesoscopic functional equivalence between imagery and perception: The case of hypnotizability. NeuroImage 2019, 200, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spina, V.; Chisari, C.; Santarcangelo, E.L. High Motor Cortex Excitability in Highly Hypnotizable Individuals: A Favourable Factor for Neuroplasticity? Neuroscience 2020, 430, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cesari, P.; Modenese, M.; Benedetti, S.; Emadi Andani, M.; Fiorio, M. Hypnosis-induced modulation of corticospinal excitability during motor imagery. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambrik, Z.; Santarcangelo, E.L.; Ghelarducci, B.; Picano, E.; Sebastiani, L. Does hypnotizability modulate the stress-related endothelial dysfunction? Brain Res. Bull. 2004, 63, 213–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jambrik, Z.; Santarcangelo, E.L.; Rudisch, T.; Varga, A.; Forster, T.; Carli, G. Modulation of pain-induced endothelial dysfunction by hypnotisability. Pain 2005, 116, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.; Santarcangelo, E.L.; Roatta, S. Does hypnotizability affect neurovascular coupling during cognitive tasks? Physiol. Behav. 2022, 257, 113915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.; Santarcangelo, E.L.; Roatta, S. Cerebrovascular reactivity during visual stimulation: Does hypnotizability matter? Brain Res. 2022, 1794, 148059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santarcangelo, E.L.; Scattina, E.; Carli, G.; Ghelarducci, B.; Orsini, P.; Manzoni, D. Can imagery become reality? Exp. Brain Res. 2010, 206, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzocchi, M.; Mecacci, G.; Zeppi, A.; Carli, G.; Santarcangelo, E.L. Hypnotizability and Performance on a Prism Adaptation Test. Cerebellum 2015, 14, 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callara, A.L.; Fontanelli, L.; Belcari, I.; Rho, G.; Greco, A.; Zelič, Ž.; Sebastiani, L.; Santarcangelo, E.L. Modulation of the heartbeat evoked cortical potential by hypnotizability and hypnosis. Psychophysiology 2023, 60, e14309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosati, A.; Belcari, I.; Santarcangelo, E.L.; Sebastiani, L. Interoceptive Accuracy as a Function of Hypnotizability. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Hypn. 2021, 69, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diolaiuti, F.; Fantozzi, M.P.T.; Di Galante, M.; D’Ascanio, P.; Faraguna, U.; Sebastiani, L.; Santarcangelo, E.L. Association of hypnotizability and deep sleep: Any role for interoceptive sensibility? Exp. Brain Res. 2020, 238, 1937–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Presciuttini, S.; Gialluisi, A.; Barbuti, S.; Curcio, M.; Scatena, F.; Carli, G.; Santarcangelo, E.L. Hypnotizability and Catechol-O-Methyltransferase (COMT) polymorphysms in Italians. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 7, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Horton, J.E.; Crawford, H.J.; Harrington, G.; Downs, J.H., 3rd. Increased anterior corpus callosum size associated positively with hypnotizability and the ability to control pain. Brain 2004, 127 Pt 8, 1741–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastos, M.A.V., Jr.; Oliveira Bastos, P.R.H.; Foscaches Filho, G.B.; Conde, R.B.; Ozaki, J.G.O.; Portella, R.B.; Iandoli, D., Jr.; Lucchetti, G. Corpus callosum size, hypnotic susceptibility and empathy in women with alleged mediumship: A controlled study. Explore 2022, 18, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGeown, W.J.; Mazzoni, G.; Vannucci, M.; Venneri, A. Structural and functional correlates of hypnotic depth and suggestibility. Psychiat. Res. 2015, 231, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.O.; Kramer, S.; Hofman, N.; Flynn, J.; Hansen, M.; Martin, V.; Pillai, A.; Buckley, P.F. A Meta-Analysis of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Effects on Brain Volume in Schizophrenia: Genotype and Serum Levels. Neuropsychobiology 2021, 80, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohira, K.; Yokota, H.; Hirano, S.; Nishimura, M.; Mukai, H.; Horikoshi, T.; Sawai, S.; Yamanaka, Y.; Yamamoto, T.; Kakeda, S.; et al. DRD2 Taq1A Polymorphism-Related Brain Volume Changes in Parkinson’s Disease: Voxel-Based Morphometry. Park. Dis. 2022, 2002, 8649195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecacci, G.; Menzocchi, M.; Zeppi, A.; Carli, G.; Santarcangelo, E.L. Body sway modulation by hypnotizability and gender during low and high demanding postural conditions. Arch. Ital. Biol. 2013, 151, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Incognito, O.; Menardo, E.; Di Gruttola, F.; Tomaiuolo, F.; Sebastiani, L.; Santarcangelo, E.L. Visuospatial imagery in healthy individuals with different hypnotizability levels. Neurosci. Lett. 2019, 690, 158–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoiland, R.L.; Caldwell, H.G.; Howe, C.A.; Nowak-Flück, D.; Stacey, B.S.; Bailey, D.M.; Paton, J.F.R.; Green, D.J.; Sekhon, M.S.; Macleod, D.B.; et al. Nitric oxide is fundamental to neurovascular coupling in humans. J. Physiol. 2020, 598, 4927–4939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeannerod, M.; Frak, V. Mental imaging of motor activity in humans. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1999, 9, 735–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillot, A.; Di Rienzo, F.; Macintyre, T.; Moran, A.; Collet, C. Imagining is Not Doing but Involves Specific Motor Commands: A Review of Experimental Data Related to Motor Inhibition. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2012, 6, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, A.J.; Boe, S.G. Imagining the way forward: A review of contemporary motor imagery theory. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 1033493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.X.; Ge, S.; Zhang, J.Q.; Hemmat, P.; Jiang, B.Y.; Liu, X.J.; Lu, X.; Yaghi, Z.; Yue, G.H. Bilateral transfer of motor performance as a function of motor imagery training: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1187175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henschke, J.U.; Pakan, J.M.P. Engaging distributed cortical and cerebellar networks through motor execution, observation, and imagery. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1165307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srzich, A.J.; Byblow, W.D.; Stinear, J.W.; Cirillo, J.; Anson, J.G. Can motor imagery and hypnotic susceptibility explain Conversion Disorder with motor symptoms? Neuropsychologia 2016, 89, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallaro, F.I.; Cacace, I.; Del Testa, M.; Andre, P.; Carli, G.; De Pascalis, V.; Rocchi, R.; Santarcangelo, E.L. Hypnotizability-related EEG alpha and theta activities during visual and somesthetic imageries. Neurosci. Lett. 2010, 470, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell, P.F. Involuntariness in hypnotic responding and dissociative symptoms. J. Trauma Dissociation 2010, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirsch, I.; Lynn, S.J. Dissociation theories of hypnosis. Psychol. Bull. 1998, 123, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirsch, I.; Lynn, S.J. Hypnotic involuntariness and the automaticity of everyday life. Am. J. Clin. Hypn. 1997, 40, 329–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynn, S.J.; Green, J.P. The sociocognitive and dissociation theories of hypnosis: Toward a rapprochement. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Hypn. 2011, 59, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acunzo, D.J.; Oakley, D.A.; Terhune, D.B. The neurochemistry of hypnotic suggestion. Am. J. Clin. Hypn. 2021, 63, 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tellegen, A.; Atkinson, G. Openness to absorbing and self-altering experiences (“absorption”), a trait related to hypnotic susceptibility. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1974, 83, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, H.J.; Brown, A.M.; Moon, C.E. Sustained attentional and disattentional abilities: Differences between low and highly hypnotizable persons. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1993, 102, 534–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colzato, L.S.; Waszak, F.; Nieuwenhuis, S.; Posthuma, D.; Hommel, B. The flexible mind is associated with the catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) Val158Met polymorphism: Evidence for a role of dopamine in the control of task-switching. Neuropsychologia 2010, 48, 2764–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raz, A.; Fan, J.; Posner, M.I. Neuroimaging and genetic associations of attentional and hypnotic processes. J. Physiol. 2006, 99, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szekely, A.; Kovacs-Nagy, R.; Bányai, E.I.; Gosi-Greguss, A.C.; Varga, K.; Halmai, Z.; Ronai, Z.; Sasvari-Szekely, M. Association between hypnotizability and the catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) polymorphism. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Hypn. 2010, 58, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, R.A.; Hung, L.; Dobson-Stone, C.; Schofield, P.R. The association between the oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) and hypnotizability. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2013, 38, 1979–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenberg, P.; Bachner-Melman, R.; Gritsenko, I.; Ebstein, R.P. Exploratory association study between catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) high/low enzyme activity polymorphism and hypnotizability. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2000, 96, 771–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rominger, C.; Weiss, E.M.; Nagl, S.; Niederstätter, H.; Parson, W.; Papousek, I. Carriers of the COMT Met/Met allele have higher degrees of hypnotizability, provided that they have good attentional control: A case of gene-trait interaction. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Hypn. 2014, 62, 455–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellani, E.; D’Alessandro, L.; Sebastiani, L. Hypnotizability and spatial attentional functions. Arch. Ital. Biol. 2007, 145, 23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Hoeft, F.; Gabrieli, J.D.; Whitfield-Gabrieli, S.; Haas, B.W.; Bammer, R.; Menon, V.; Spiegel, D. Functional brain basis of hypnotizability. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2012, 69, 1064–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strick, P.L.; Dum, R.P.; Fiez, J.A. Cerebellum and nonmotor function. Ann. Rev. Neurosci. 2009, 32, 413–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bocci, T.; Barloscio, D.; Parenti, L.; Sartucci, F.; Carli, G.; Santarcangelo, E.L. High Hypnotizability Impairs the Cerebellar Control of Pain. Cerebellum 2017, 16, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocci, T.; Santarcangelo, E.; Vannini, B.; Torzini, A.; Carli, G.; Ferrucci, R.; Priori, A.; Valeriani, M.; Sartucci, F. Cerebellar direct current stimulation modulates pain perception in humans. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 2015, 33, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laricchiuta, D.; Picerni, E.; Cutuli, D.; Petrosini, L. Cerebellum, Embodied Emotions, and Psychological Traits. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2022, 1378, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Z.; Li, H.; Naser, P.V.; Oswald, M.J.; Kuner, R. Suppression of Neuropathic Pain and Comorbidities by Recurrent Cycles of Repetitive Transcranial Direct Current Motor Cortex Stimulation in Mice. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, W.Y.; Stohler, C.S.; Herr, D.R. Role of the Prefrontal Cortex in Pain Processing. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 56, 1137–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seminowicz, D.A.; Moayedi, M. The Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex in Acute and Chronic Pain. J. Pain. 2017, 18, 1027–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, A.D. How do you feel? Interoception: The sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2022, 3, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Critchley, H.D.; Garfinkel, S.N. Interoception and emotion. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2017, 17, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsakiris, M.; Critchley, H. Interoception beyond homeostasis: Affect, cognition and mental health. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2016, 371, 20160002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehling, W.E.; Acree, M.; Stewart, A.; Silas, J.; Jones, A. The Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness, Version 2 (MAIA-2). PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porges, S.W. Body Perception Questionnaire; Laboratory of Developmental Assessment, University of Maryland: College Park, MD, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Fontanelli, L.; Spina, V.; Chisari, C.; Siciliano, G.; Santarcangelo, E.L. Is hypnotic assessment relevant to neurology? Neurol. Sci. 2022, 43, 4655–4661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, B.; Eddy, B.; Galvin-McLaughlin, D.; Betz, G.; Oken, B.; Fried-Oken, M. A systematic review of research on augmentative and alternative communication brain-computer interface systems for individuals with disabilities. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 952380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terreni, C. Efficacia di un Training Immaginativo sul Movimento: Studio Sperimentale. Master’s Thesis, Pisa University, Pisa, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Han, K.; Liu, J.; Tang, Z.; Su, W.; Liu, Y.; Lu, H.; Zhang, H. Effects of excitatory transcranial magnetic stimulation over the different cerebral hemispheres dorsolateral prefrontal cortex for post-stroke cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1102311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzawa, Y.; Kwon, T.G.; Lennon, R.J.; Lerman, L.O.; Lerman, A. Prognostic Value of Flow-Mediated Vasodilation in Brachial Artery and Fingertip Artery for Cardiovascular Events: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2015, 4, e002270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grześk, G.; Witczyńska, A.; Węglarz, M.; Wołowiec, Ł.; Nowaczyk, J.; Grześk, E.; Nowaczyk, A. Soluble Guanylyl Cyclase Activators-Promising Therapeutic Option in the Pharmacotherapy of Heart Failure and Pulmonary Hypertension. Molecules 2023, 28, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mućka, S.; Miodońska, M.; Jakubiak, G.K.; Starzak, M.; Cieślar, G.; Stanek, A. Endothelial Function Assessment by Flow-Mediated Dilation Method: A Valuable Tool in the Evaluation of the Cardiovascular System. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 11242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar Cervantes, C.; Esteban Fernández, A.; Recio Mayoral, A.; Mirabet, S.; González Costello, J.; Rubio Gracia, J.; Núñez Villota, J.; González Franco, Á.; Bonilla Palomas, J.L. Identifying the patient with heart failure to be treated with vericiguat. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2023, 39, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishi, T. Regulation of the sympathetic nervous system by nitric oxide and oxidative stress in the rostral ventrolateral medulla: 2012 Academic Conference Award from the Japanese Society of Hypertension. Hypertens. Res. 2013, 36, 845–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quarti-Trevano, F.; Dell’Oro, R.; Cuspidi, C.; Ambrosino, P.; Grassi, G. Endothelial, Vascular and Sympathetic Alterations as Therapeutic Targets in Chronic Heart Failure. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huerta de la Cruz, S.; Santiago-Castañeda, C.L.; Rodríguez-Palma, E.J.; Medina-Terol, G.J.; López-Preza, F.I.; Rocha, L.; Sánchez-López, A.; Freeman, K.; Centurión, D. Targeting hydrogen sulfide and nitric oxide to repair cardiovascular injury after trauma. Nitric Oxide Biol. Chem. 2022, 129, 82–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeev, V.; Chai, Y.L.; Poh, L.; Selvaraji, S.; Fann, D.Y.; Jo, D.G.; De Silva, T.M.; Drummond, G.R.; Sobey, C.G.; Arumugam, T.V.; et al. Chronic cerebral hypoperfusion: A critical feature in unravelling the etiology of vascular cognitive impairment. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2023, 11, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uemura, M.T.; Maki, T.; Ihara, M.; Lee, V.M.Y.; Trojanowski, J.Q. Brain Microvascular Pericytes in Vascular Cognitive Impairment and Dementia. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2020, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinski, T. Nitric oxide and nitroxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis 2007, 11, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santarcangelo, E.L.; Paoletti, G.; Balocchi, R.; Carli, G.; Morizzo, C.; Palombo, C.; Varanini, M. Hypnotizability modulates the cardiovascular correlates of participantive relaxation. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Hypn. 2012, 60, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santarcangelo, E.L.; Balocchi, R.; Scattina, E.; Manzoni, D.; Bruschini, L.; Ghelarducci, B.; Varanini, M. Hypnotizability-dependent modulation of the changes in heart rate control induced by upright stance. Brain Res. Bull. 2008, 75, 692–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, J.W.; Benson, H.; Arns, P.A.; Stainbrook, G.L.; Landsberg, G.L.; Young, J.B.; Gill, A. Reduced sympathetic nervous system responsivity associated with the relaxation response. Science 1982, 215, 190–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruzyla-Smith, P.; Barabasz, A.; Barabasz, M.; Warner, D. Effects of hypnosis on the immune response: B-cells, T-cells, helper and suppressor cells. Am. J. Clin. Hypn. 1995, 38, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, Z.A.; Puskás, L.G.; Juhász, A.; Rimanóczy, A.; Hackler, L., Jr.; Kátay, L.; Gali, Z.; Vetró, A.; Janka, Z.; Kálmán, J. Hypnosis upregulates the expression of immune-related genes in lymphocytes. Psychother. Psychosom. 2008, 77, 257–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, G.J.; Bughi, S.; Morrison, J.; Tanavoli, S.; Tanavoli, S.; Zadeh, H.H. Hypnosis, differential expression of cytokines by T-cell subsets, and the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis. Am. J. Clin. Hypn. 2003, 45, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruzelier, J.; Smith, F.; Nagy, A.; Henderson, D. Cellular and humoral immunity, mood and exam stress: The influences of self-hypnosis and personality predictors. Int. J. Psychophysiol. Off. J. Int. Organ. Psychophysiol. 2001, 42, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santarcangelo, E.L.; Emdin, M.; Picano, E.; Raciti, M.; Macerata, A.; Michelassi, C.; Kraft, G.; Riva, A.; L’Abbate, A. Can hypnosis modify the sympathetic-parasympathetic balance at heart level? J. Ambul. Monit. 1992, 5, 187–191. [Google Scholar]

- De Benedittis, G. Hypnobiome: A New, Potential Frontier of Hypnotherapy in the Treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome-A Narrative Review of the Literature. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Hypn. 2022, 70, 286–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachariae, R.; Jørgensen, M.M.; Bjerring, P.; Svendsen, G. Autonomic and psychological responses to an acute psychological stressor and relaxation: The influence of hypnotizability and absorption. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Hypn. 2000, 48, 388–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, C.; Dilthey, A.; Finzer, P. The role of microbiome-host interactions in the development of Alzheimer s disease. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1151021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, S.K.; Ito, K.; Dhib-Jalbut, S. Interaction of the Gut Microbiome and Immunity in Multiple Sclerosis: Impact of Diet and Immune Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Gao, G.; Kwok, L.Y.; Sun, Z. Gut microbiome-targeted therapies for Alzheimer’s disease. Gut Microbes. 2023, 15, 2271613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, S.; Shin, Y.; Han, S.; Kwon, J.; Choi, T.G.; Kang, I.; Kim, S.S. The Gut-Brain Axis in Schizophrenia: The Implications of the Gut Microbiome and SCFA Production. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McVey Neufeld, S.F.; Ahn, M.; Kunze, W.A.; McVey Neufeld, K.A. Adolescence, the microbiota-gut-brain axis, and the emergence of psychiatric disorders. Biol. Psychiatry. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Lauro, M.; Guerriero, C.; Cornali, K.; Albanese, M.; Costacurta, M.; Mercuri, N.B.; Di Daniele, N.; Noce, A. Linking Migraine to Gut Dysbiosis and Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mázala-de-Oliveira, T.; Silva, B.T.; Campello-Costa, P.; Carvalho, V.F. The Role of the Adrenal-Gut-Brain Axis on Comorbid Depressive Disorder Development in Diabetes. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Wu, X. Modulation of the Gut Microbiota in Memory Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease via the Inhibition of the Parasympathetic Nervous System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presciuttini, S.; Curcio, M.; Sciarrino, R.; Scatena, F.; Jensen, M.P.; Santarcangelo, E.L. Polymorphism of Opioid Receptors μ1 in Highly Hypnotizable Subjects. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Hypn. 2018, 66, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weizenhoffer, A.M.; Hilgard, E.R. Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale, Forms A and B; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Baghdadi, G.; Nasrabadi, A.M. Comparison of different EEG features in estimation of hypnosis susceptibility level. Comput. Biol. Med. 2012, 42, 590–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghdadi, G.; Nasrabadi, A.M. EEG phase synchronization during hypnosis induction. J. Med. Eng. Technol. 2012, 36, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yargholi, E.; Nasrabadi, A.M. Chaos-chaos transition of left hemisphere EEGs during standard tasks of Waterloo-Stanford Group Scale of hypnotic susceptibility. J. Med. Eng. Technol. 2015, 39, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiarucci, R.; Madeo, D.; Loffredo, M.I.; Castellani, E.; Santarcangelo, E.L.; Mocenni, C. Cross-evidence for hypnotic susceptibility through nonlinear measures on EEGs of non-hypnotized subjects. Sci. Rep. 2014, 8, 4–5610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landry, M.; da Silva Castanheira, J.; Sackur, J.; Raz, A.; Ogez, D.; Rainville, P.; Jerbi, K. Unravelling the neural dynamics of hypnotic susceptibility: Aperiodic neural activity as a central feature of hypnosis. bioRchive 2023, preprint. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Malloggi, E.; Santarcangelo, E.L. Physiological Correlates of Hypnotizability: Hypnotic Behaviour and Prognostic Role in Medicine. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1632. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13121632

Malloggi E, Santarcangelo EL. Physiological Correlates of Hypnotizability: Hypnotic Behaviour and Prognostic Role in Medicine. Brain Sciences. 2023; 13(12):1632. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13121632

Chicago/Turabian StyleMalloggi, Eleonora, and Enrica L. Santarcangelo. 2023. "Physiological Correlates of Hypnotizability: Hypnotic Behaviour and Prognostic Role in Medicine" Brain Sciences 13, no. 12: 1632. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13121632

APA StyleMalloggi, E., & Santarcangelo, E. L. (2023). Physiological Correlates of Hypnotizability: Hypnotic Behaviour and Prognostic Role in Medicine. Brain Sciences, 13(12), 1632. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13121632