Is That “Mr.” or “Ms.” Lemon? An Investigation of Grammatical and Semantic Gender on the Perception of Household Odorants

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Linguistic Relativism

1.2. Linguistic Relativism and Grammatical Gender

1.3. Olfactory Perception and Grammatical Gender

1.4. Linguistic Relativism, Cultural Anthropomorphism, and Olfaction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Materials

2.3. Design

2.3.1. Procedure

2.3.2. Analysis of Adjectives

3. Results

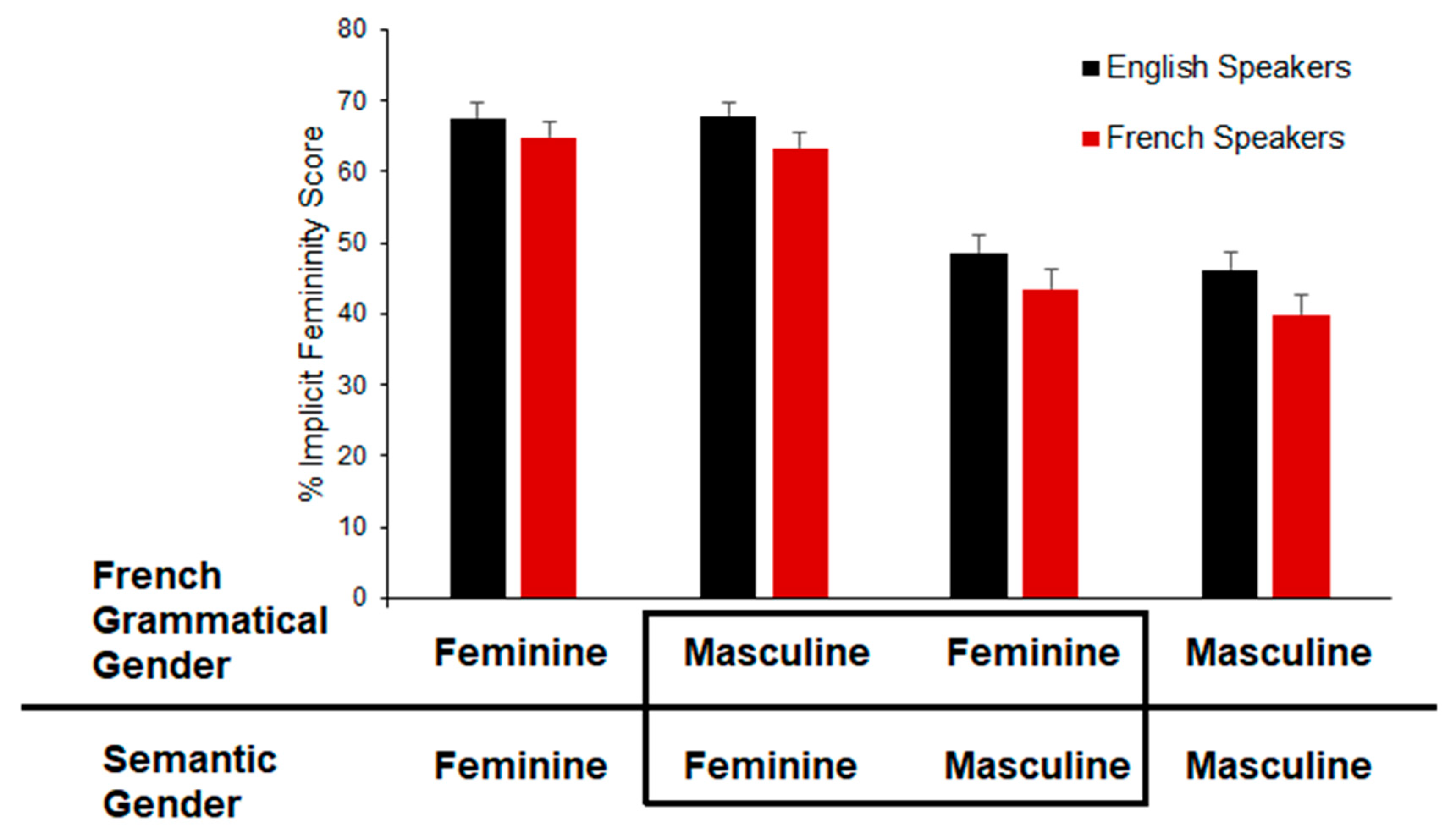

3.1. Implicit Ratings Based on Odorant Descriptions

3.2. Analysis of the Primary Hypothesis

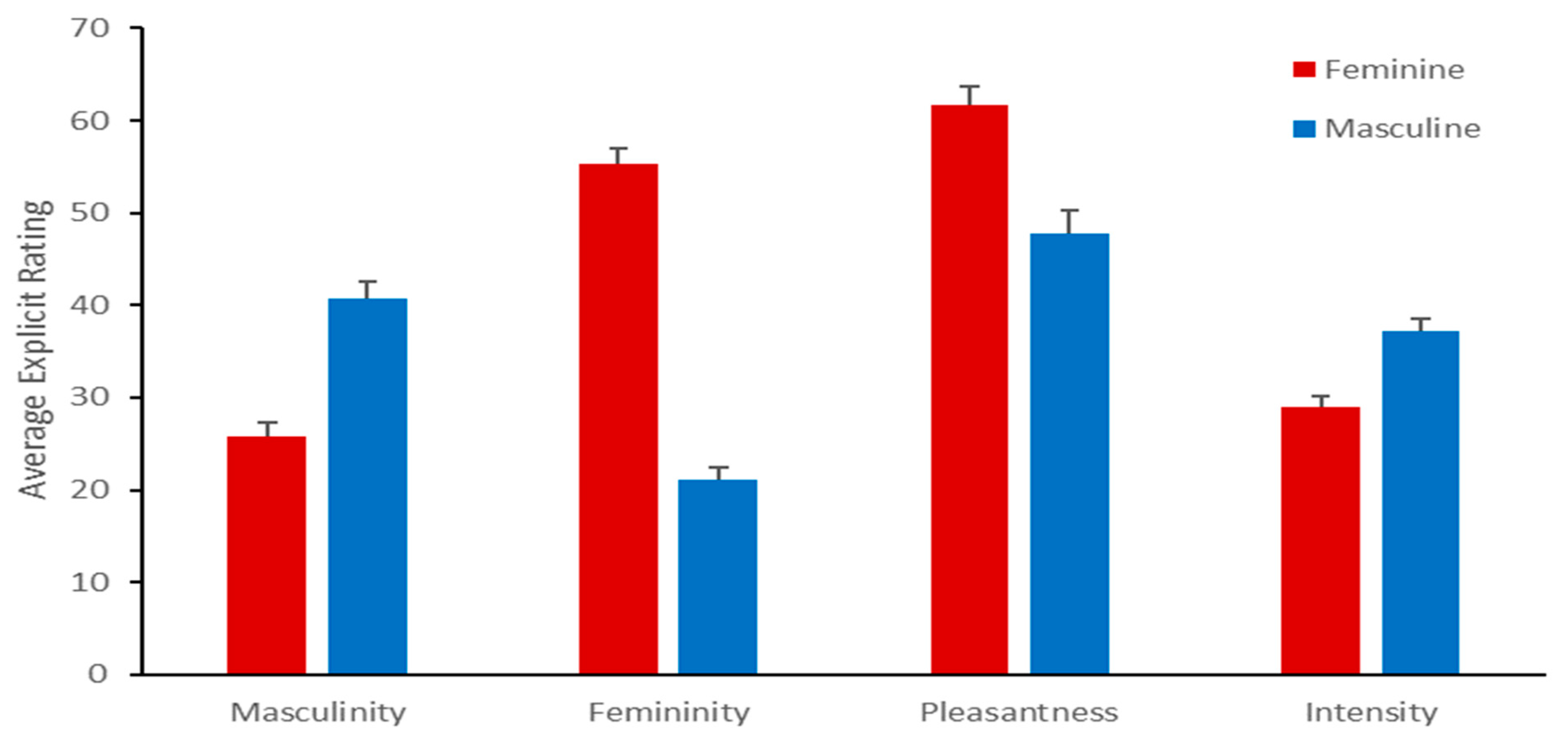

3.3. Explicit Ratings as a Secondary Test of the Primary Hypothesis

4. Discussion

4.1. Grammatical Gender Did Not Influence the Description of Household Odorants

4.2. Cultural Gender Personification of Household Odorants Is Possible

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cain, W.S.; Goodwin, M.; Gooding, K.; Regnier, F. To Know with the Nose: Keys to Odor Identification. Science 1979, 203, 467–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Wijk, R.A.; Cain, W.S. Odor quality: Discrimination versus free and cued identification. Percept. Psychophys. 1994, 56, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desor, J.A.; Beauchamp, G.K. The human capacity to transmit olfactory information. Percept Psychophys 1974, 16, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engen, T.; Ross, B.M. Long-term memory of odors with and without verbal descriptions. J. Exp. Psychol. 1973, 100, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulmont-Rossé, C.; Issanchou, S.; Köster, E.P. Odor Naming Methodology: Correct Identification with Multiple-choice versus Repeatable Identification in a Free Task. Chem. Senses 2005, 30, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iatropoulos, G.; Herman, P.; Lansner, A.; Karlgren, J.; Larsson, M.; Olofsson, J.K. The language of smell: Connecting linguistic and psychophysical properties of odor descriptors. Cognition 2018, 178, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, A. Cultural Factors Shape Olfactory Language. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2015, 19, 629–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, A.; Burenhult, N. Odors are expressible in language, as long as you speak the right language. Cognition 2014, 130, 266–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, W.S. Differential Sensitivity for Smell: “Noise” at the Nose. Science 1977, 195, 796–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doty, R.L.; Shaman, P.; Kimmelman, C.P.; Dann, M.S. University of pennsylvania smell identification test: A rapid quantitative olfactory function test for the clinic. Laryngoscope 1984, 94, 176–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, J.K.; Rogalski, E.; Harrison, T.; Mesulam, M.-M.; Gottfried, J.A. A cortical pathway to olfactory naming: Evidence from primary progressive aphasia. Brain 2013, 136, 1245–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olofsson, J.K.; Gottfried, J.A. The muted sense: Neurocognitive limitations of olfactory language. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2015, 19, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olofsson, J.K.; Gottfried, J.A. Response to Majid: Neurocognitive and Cultural Approaches to Odor Naming are Complementary. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2015, 19, 630–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorig, T.S. On the similarity of odor and language perception. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 1999, 23, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, A. Olfactory Language Requires an Integrative and Interdisciplinary Approach. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2021, 25, 421–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, J.K.; Pierzchajlo, S. Olfactory Language: Context Is Everything. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2021, 25, 419–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, W.S.; Potts, B.C. Switch and Bait: Probing the Discriminative Basis of Odor Identification via Recognition Memory. Chem. Senses 1996, 21, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engen, T. Remembering odors and their names. Am. Sci. 1987, 75, 497–503. [Google Scholar]

- Ayabe-Kanamura, S.; Schicker, I.; Laska, M.; Hudson, R.; Distel, H.; Kobayakawa, T.; Saito, S. Differences in Perception of Everyday Odors: A Japanese-German Cross-cultural Study. Chem. Senses 1998, 23, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distel, H.; Hudson, R. Judgement of odor intensity is influenced by subjects’ knowledge of the odor source. Chem. Senses 2001, 26, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herz, R.S.; von Clef, J. The influence of verbal labeling on the perception of odors: Evidence for olfactory illusions? Perception 2001, 30, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herz, R.S. The Effect of Verbal Context on Olfactory Perception. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2003, 132, 595–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sapir, E. Culture, Language and Personality; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Whorf, B.L. Language, mind, and reality. ETC A Rev. Gen. Semant. 1952, 9, 167–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boroditsky, L.; Schmidt, L.A.; Phillips, W. Sex, Syntax, and Semantics. In Language in Mind: Advances in the Study of Language and Thought; Getner, D., Goldin-Meadow, S., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 61–79. [Google Scholar]

- Samuel, S.; Cole, G.; Eacott, M.J. Grammatical gender and linguistic relativity: A systematic review. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2019, 26, 1767–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidoff, J.; Davies, I.; Roberson, D. Colour categories in a stone-age tribe. Nature 1999, 398, 203–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heider, E.R. Universals in color naming and memory. J. Exp. Psychol. 1972, 93, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucy, J.A. Recent Advances in the Study of Linguistic Relativity in Historical Context: A Critical Assessment. Lang. Learn. 2016, 66, 487–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubelli, R.; Paolieri, D.; Lotto, L.; Job, R. The effect of grammatical gender on object categorization. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2011, 37, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenuks, A.; Phillips, W.; Dalca, I.; Kim, C.; Boroditsky, L. Effects of Grammatical Gender on Object Description. In Proceedings of the 39th Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society, CogSci 2017, London, UK, 16–29 July 2017; pp. 1060–1065. Available online: https://cogsci.mindmodeling.org/2017/papers/0207/paper0207.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Mills, A.E. The Acquisition of Gender: A Study of English and German; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Guiora, A.Z.; Acton, W.R. Personality and language behavior: A restatement 1. Lang. Learn. 1979, 29, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutonnet, B.; Athanasopoulos, P.; Thierry, G. Unconscious effects of grammatical gender during object categorisation. Brain Res. 2012, 1479, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigliocco, G.; Vinson, D.P.; Paganelli, F.; Dworzynski, K. Grammatical Gender Effects on Cognition: Implications for Language Learning and Language Use. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2005, 134, 501–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, S.; Roberson, D. What constrains grammatical gender effects on semantic judgements? Evidence from Portuguese. J. Cogn. Psychol. 2011, 23, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mickan, A.; Schiefke, M.; Stefanowitsch, A. Key is a llave is a Schlussel: A failure to replicate an experiment from Boroditsky et al. 2003. In Yearbook of the German Cognitive Linguistics Association; Stefanowitsch, A., Niemeier, S., Eds.; De Gruyter Mouton: Berlin, Germany, 2014; Volume 2, pp. 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beller, S.; Brattebø, K.F.; Lavik, K.O.; Reigstad, R.D.; Bender, A. Culture or language: What drives effects of grammatical gender? Cogn. Linguist 2015, 26, 331–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoladis, E.; Westbury, C.; Foursha-Stevenson, C. English Speakers’ Implicit Gender Concepts Influence Their Processing of French Grammatical Gender: Evidence for Semantically Mediated Cross-Linguistic Influence. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 740920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, M.A.; Hall, A.E. Anthropomorphism, empathy, and perceived communicative ability vary with phylogenetic relatedness to humans. J. Social, Evol. Cult. Psychol. 2010, 4, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sera, M.D.; Berge, C.A.; del Castillo Pintado, J. Grammatical and conceptual forces in the attribution of gender by English and Spanish speakers. Cogn. Dev. 1994, 9, 261–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay, D.G. Protypicality among metaphors: On the relative frequency of personification and spatial metaphors in literature written for children versus adults. Metaphor Symb. 1986, 1, 87–107. [Google Scholar]

- MacKay, D.G.; Konishi, T. Personification and the pronoun problem. Women’s Stud. Int. Q. 1980, 3, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorkston, E.; De Mello, G.E. Linguistic Gender Marking and Categorization. J. Consum. Res. 2005, 32, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecit, A.; Lowrey, T.M.; Shrum, L.J. Grammatical gender and anthropomorphism:“It” depends on the language. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 123, 503–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, K.-L.; Rosero, S.J.; Doty, R.L. Odors and the Perception of Hygiene. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2005, 100, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zellner, D.A.; McGarry, A.; Mattern-McClory, R.; Abreu, D. Masculinity/Femininity of Fine Fragrances Affects Color-Odor Correspondences: A Case for Cognitions Influencing Cross-Modal Correspondences. Chem. Senses 2008, 33, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiore, A.M. Effect of composition of olfactory cues on impressions of personality. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 1992, 20, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovis, N.L.; Sheehe, P.R.; White, T.L. Scent of a Woman—Or Man: Odors Influence Person Knowledge. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzo, M. Relevant psychological dimensions in the perceptual space of perfumery odors. Food Qual. Prefer. 2008, 19, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speed, L.; Majid, A. Grammatical gender affects odor cognition. In Proceedings of the 38th Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society, CogSci 2016, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 10–13 August 2016; pp. 1451–1456. Available online: https://cogsci.mindmodeling.org/2016/papers/0257/paper0257.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Speed, L.J.; Majid, A. Linguistic features of fragrances: The role of grammatical gender and gender associations. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 2019, 81, 2063–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdenzi, C.; Joussain, P.; Digard, B.; Luneau, L.; Djordjevic, J.; Bensafi, M. Individual Differences in Verbal and Non-Verbal Affective Responses to Smells: Influence of Odor Label Across Cultures. Chem. Senses 2017, 42, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, V.; Blumenfeld, H.K.; Kaushanskaya, M. The Language Experience and Proficiency Questionnaire (LEAP-Q): Assessing Language Profiles in Bilinguals and Multilinguals. J. Speech Lang. Heart Res. 2007, 50, 940–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushanskaya, M.; Blumenfeld, H.K.; Marian, V. The Language Experience and Proficiency Questionnaire (LEAP-Q): Ten years later. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 2020, 23, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, A.; White, T.L.; Zampini, M. Odor descriptions are influenced by both grammatical and semantic gender in Spanish speakers. In Proceedings of the Association for Psychological Science Meeting, Chicago, IL, USA, 24–27 May 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Collins-Robert French College Dictionary, 8th ed.; HarperCollins Publishers and Dictionaries: New York, NY, USA, 2012.

- Bartoshuk, L.M.; Duffy, V.B.; Fast, K.; Green, B.G.; Prutkin, J.; Snyder, D.J. Labeled scales (e.g., category, Likert, VAS) and invalid across-group comparisons: What we have learned from genetic variation in taste. Food Qual. Prefer 2003, 2, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Wood, A.; Green, B.G. Derivation and Evaluation of a Labeled Hedonic Scale. Chem. Senses 2009, 34, 739–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. An Application of Hierarchical Kappa-type Statistics in the Assessment of Majority Agreement among Multiple Observers. Biometrics 1977, 33, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sezille, C.; Fournel, A.; Rouby, C.; Rinck, F.; Bensafi, M. Hedonic appreciation and verbal description of pleasant and unpleasant odors in untrained, trainee cooks, flavorists, and perfumers. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kousta, S.-T.; Vinson, D.P.; Vigliocco, G. Investigating linguistic relativity through bilingualism: The case of grammatical gender. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2008, 34, 843–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, M.; Schalk, L.; Saalbach, H.; Okada, H. All Giraffes Have Female-Specific Properties: Influence of Grammatical Gender on Deductive Reasoning About Sex-Specific Properties in German Speakers. Cogn. Sci. 2014, 38, 514–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laing, D.G.; Francis, G.W. The capacity of humans to identify odors in mixtures. Physiol. Behav. 1989, 46, 809–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosjean, F. The bilingual’s language modes. In One Mind, Two Languages: Bilingual Language Processing; Nicol, J., Ed.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2001; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Athanasopoulos, P.; Bylund, E.; Montero-Melis, G.; Damjanovic, L.; Schartner, A.; Kibbe, A.; Thierry, G. Two languages, two minds: Flexible cognitive processing driven by language of operation. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 26, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, J.F.; Bialystok, E. Understanding the consequences of bilingualism for language processing and cognition. J. Cogn. Psychol. 2013, 25, 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, J.F.; Dussias, P.E.; Bogulski, C.A.; Valdes Kroff, J.R. Juggling two languages in one mind: What bilinguals tell us about language processing and its consequences for cognition. Psychol. Learn Motiv. 2012, 56, 229–262. [Google Scholar]

- Grosjean, F. Neurolinguists, beware! The bilingual is not two monolinguals in one person. Brain Lang. 1989, 36, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstätter, P.R. Über sprachliche bestimmungsleistungen: Das problem des grammatikalischen geschlechts von sonne und mond [On linguistic performances of connotation: The problem of the grammatical gender of sun and moon]. Z. Für Exp. Und Angew. Psychol. 1963, 10, 91–108. [Google Scholar]

- Doty, R.L.; Green, P.A.; Ram, C.; Yankell, S.L. Communication of gender from human breath odors: Relationship to perceived intensity and pleasantness. Horm. Behav. 1982, 16, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doty, R.L.; Orndorff, M.M.; Leyden, J.; Kligman, A. Communication of gender from human axillary odors: Relationship to perceived intensity and hedonicity. Behav. Biol. 1978, 23, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broverman, I.K.; Vogel, S.R.; Broverman, D.M.; Clarkson, F.E.; Rosenkrantz, P.S. Sex-Role Stereotypes: A Current Appraisal. J. Soc. Issues 1972, 28, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutic, S.; Moellers, E.M.; Wiesmann, M.; Freiherr, J. Chemosensory Communication of Gender Information: Masculinity Bias in Body Odor Perception and Femininity Bias Introduced by Chemosignals During Social Perception. Front. Psychol. 2016, 6, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foundalis, H.E. Evolution of gender in Indo-European languages. In Proceedings of the 24th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society, Fairfax, VA, USA, 7–10 August 2002; pp. 304–309. [Google Scholar]

- Lindqvist, A. Gender Categorization of Perfumes: The Difference between Odour Perception and Commercial Classification. NORA-Nord. J. Fem. Gend. Res. 2013, 21, 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeshurun, Y.; Sobel, N. An Odor is Not Worth a Thousand Words: From Multidimensional Odors to Unidimensional Odor Objects. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2010, 61, 219–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firestone, C.; Scholl, B.J. Cognition does not affect perception: Evaluating the evidence for “top-down” effects. Behav. Brain Sci. 2016, 39, e229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, D.; Rouby, C.; Sicard, G. Catégories s’emantiques et sensorialités: De l’espace visuel à l’espace olfactif. Enfance 1997, 1, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| French | English | |

|---|---|---|

| N | 16 | 16 |

| Gender: N Female (%) | 12 (75%) | 8 (50%) |

| Age: mean (sd) | 22.81 (6.5) | 22.56 (4.0) |

| Leap-Q Results | Second Language: 15 English Proficiency > 7: n = 10 Proficiency 5–6: n = 3 Proficiency < 4: n = 2 1 Spanish Proficiency N/A | Second Language: 9 French: Proficiency > 7: n = 1 Proficiency 5–6: n = 3 Proficiency < 4: n = 5 4 Other (Gendered): Greek: Proficiency 9 Lithuanian: Proficiency 7 Spanish: Proficiency 1 Gujarati: Proficiency 0 3 Other (Non-Gendered): Mandarin: Proficiency 8 Cantonese: Proficiency 6 Japanese: Proficiency 2 |

| N Bilingual (%) | 7 (44%) | 5 (31.3%) |

| Odorant | English Semantic Gender | French Grammatical Gender | Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Onion | Masculine | Masculine | IFF |

| Pepper (spice) | Masculine | Masculine | IFF |

| Peach | Feminine | Feminine | IFF |

| Banana | Feminine | Feminine | IFF |

| Peanut | Masculine | Feminine | IFF |

| Licorice | Masculine | Feminine | IFF |

| Honey | Feminine | Masculine | IFF |

| Butter | Feminine | Masculine | IFF |

| Potato | Masculine | Feminine | PiCs |

| Beer | Masculine | Feminine | Heineken |

| Cantaloupe | Feminine | Masculine | IFF |

| Lemon | Feminine | Masculine | IFF |

| Pine | Masculine | Masculine | IFF |

| Garlic | Masculine | Masculine | IFF |

| Orange | Feminine | Feminine | IFF |

| Rose | Feminine | Feminine | IFF |

| Implicit Femininity | Explicit Pleasantness | Explicit Intensity | Explicit Masculinity | Explicit Femininity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | French | English | French | English | French | English | French | English | French | English |

| Onion | 39.6 (20.4) | 37.1 (14.8) | 29.8 (19.1) | 35.6 (16.4) | 57.4 (13.1) | 51 (19.4) | 17.2 (20.8) | 32.2 (27) | 6.3 (10) | 11.5 (11.9) |

| Pepper | 42.7 (19.3) | 53.1 (20.2) | 49.4 (16) | 57.1 (14) | 39.2 (15.5) | 34.7 (23) | 64.5 (21.6) | 39.6 (20.8) | 18.5 (21.1) | 29.5 (21.9) |

| Peach | 69.3 (12.3) | 71.3 (9.7) | 74.2 (11.1) | 71.5 (14.9) | 28.2 (10.9) | 34.1 (22.2) | 16.4 (15.3) | 24.3 (24.5) | 78.7 (21.3) | 76 (19.8) |

| Banana | 66.2 (12.2) | 67.9 (15.2) | 66.4 (14.1) | 61 (16.4) | 24.5 (12.4) | 28.9 (23.1) | 25.5 (15.3) | 31.3 (23.6) | 55.9 (17.6) | 45.1 (23.8) |

| Peanut | 44.3 (20.9) | 46.3 (22.4) | 53.9 (10.1) | 48.7 (16.6) | 33.1 (18.9) | 26.2 (13.4) | 35.3 (22.5) | 32.3 (24.2) | 20.6 (16.9) | 22.6 (21) |

| Licorice | 41.1 (17.7) | 50.4 (16.3) | 49.1 (23.4) | 55.8 (15.6) | 39 (18) | 29.8 (15.5) | 35.1 (24.5) | 38.6 (17.7) | 32.3 (30.6) | 40.1 (25.9) |

| Honey | 62.7 (17.6) | 70.4 (10.9) | 58.7 (15.4) | 57.6 (11.7) | 29.8 (15.4) | 30.3 (14) | 28.9 (31.8) | 31 (18.4) | 50.4 (27.6) | 48.6 (19.5) |

| Butter | 64 (20.7) | 64.2 (14.2) | 51.3 (14.7) | 56 (18) | 19.9 (12.4) | 20.3 (10.4) | 18.3 (16) | 23.6 (19.6) | 35.3 (27.7) | 32.8 (26.2) |

| Potato | 46.2 (20.7) | 49.2 (16.8) | 43.2 (14) | 42.5 (10.2) | 18 (10.1) | 31 (20.4) | 32.5 (31.8) | 39.3 (26.8) | 17.2 (21.4) | 17.4 (25.3) |

| Beer | 42 (22.2) | 48.8 (23.9) | 48.7 (21.4) | 57.7 (19.9) | 36.7 (18.1) | 29.1 (15.9) | 62.1 (27.2) | 63 (20.4) | 18.9 (17.7) | 18.6 (17.5) |

| Cantaloupe | 69 (10.7) | 62.5 (15.8) | 58.7 (10.4) | 47.7 (12.1) | 17 (9.2) | 22.1 (15.8) | 16.9 (19.4) | 18.1 (15.2) | 58.3 (17.3) | 44.5 (26.3) |

| Lemon | 58.2 (15.2) | 74.2 (13.5) | 68.9 (13.9) | 70.3 (10.4) | 30.3 (14.4) | 38 (22.4) | 35.5 (23) | 36.6 (20.4) | 51.4 (26.1) | 54.6 (20.2) |

| Pine | 48.9 (21.3) | 63.3 (11.7) | 66.1 (15.1) | 63 (14.8) | 37.5 (20) | 30.4 (18.3) | 56.9 (34.9) | 54.6 (14.1) | 35 (24.4) | 32.7 (25.5) |

| Garlic | 29.4 (16.7) | 31.3 (16.1) | 34.6 (19.3) | 30.3 (16.3) | 52.3 (19.8) | 50.6 (20.5) | 24.9 (23.3) | 24.3 (27.1) | 9.2 (15.2) | 8.2 (10.3) |

| Orange | 66.2 (18.9) | 73.3 (13.3) | 68.2 (14.1) | 69.4 (11.1) | 25.4 (11.7) | 31.4 (16.8) | 34.5 (21.9) | 38.7 (22.4) | 60.3 (19.7) | 51.1 (25.7) |

| Rose | 57.3 (25.2) | 57.9 (22.5) | 53.4 (14.7) | 53.9 (15.7) | 39.8 (23) | 41.8 (23.2) | 12.1 (17.3) | 19.8 (27.9) | 75.1 (30) | 67.4 (27) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

White, T.L.; Cunningham, C.M.; Zampini, M.L. Is That “Mr.” or “Ms.” Lemon? An Investigation of Grammatical and Semantic Gender on the Perception of Household Odorants. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 1313. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12101313

White TL, Cunningham CM, Zampini ML. Is That “Mr.” or “Ms.” Lemon? An Investigation of Grammatical and Semantic Gender on the Perception of Household Odorants. Brain Sciences. 2022; 12(10):1313. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12101313

Chicago/Turabian StyleWhite, Theresa L., Caitlin M. Cunningham, and Mary L. Zampini. 2022. "Is That “Mr.” or “Ms.” Lemon? An Investigation of Grammatical and Semantic Gender on the Perception of Household Odorants" Brain Sciences 12, no. 10: 1313. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12101313

APA StyleWhite, T. L., Cunningham, C. M., & Zampini, M. L. (2022). Is That “Mr.” or “Ms.” Lemon? An Investigation of Grammatical and Semantic Gender on the Perception of Household Odorants. Brain Sciences, 12(10), 1313. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12101313