Abstract

Hypnosis has proven a powerful method in indications such as pain control and anxiety reduction. As recently discussed, it has been yielding increased attention from medical/dental perspectives. This systematic review (PROSPERO-registration-ID-CRD42021259187) aimed to critically evaluate and discuss functional changes in brain activity using hypnosis by means of different imaging techniques. Randomized controlled trials, cohort, comparative, cross-sectional, evaluation and validation studies from three databases—Cochrane, Embase and Medline via PubMed from January 1979 to August 2021—were reviewed using an ad hoc prepared search string and following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. A total of 10,404 articles were identified, 1194 duplicates were removed and 9190 papers were discarded after consulting article titles/abstracts. Ultimately, 20 papers were assessed for eligibility, and 20 papers were included after a hand search (ntotal = 40). Despite a broad heterogenicity of included studies, evidence of functional changes in brain activity using hypnosis was identified. Electromyography (EMG) startle amplitudes result in greater activity in the frontal brain area; amplitudes using Somatosensory Event-Related Potentials (SERPs) showed similar results. Electroencephalography (EEG) oscillations of θ activity are positively associated with response to hypnosis. EEG results showed greater amplitudes for highly hypnotizable subjects over the left hemisphere. Less activity during hypnosis was observed in the insula and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC).

Keywords:

brain activity; CT; EEG; functional changes; fMRI; imaging technique; hypnosis; PET; SPECT; systematic review 1. Introduction

Hypnosis is defined as “a state of consciousness involving focused attention and reduced peripheral awareness characterized by an enhanced capacity for response to suggestion,” according to the American Psychological Association (APA) Division 30 [1]. Hypnosis changes the state of consciousness of a person and allows unconscious experiences to become a modified way of looking at reality [2]. Judging by empirical evidence of its effectiveness in clinically diverse fields of application, hypnosis is furthermore described as an amount of biological, cognitive, and social perspectives [3]. In the state of hypnotic trance, control of the consciousness is in the background, modified by attention, concentration and letting go of thoughts while access to the unconsciousness is created [4,5]. Neutral hypnosis involves states of relaxation in which the subject responds only to important or particularly strong environmental stimuli and has reduced perception to peripheral stimuli [1,2]. Increasing activation in the visual center under hypnosis is related to a subjectively perceived degree of relaxation [2]. This means that the degree of subjectively perceived relaxation is usually greater in deep hypnosis than in a light hypnotic trance because the focus of attention on the inner experience is increased, allowing an increased capacity for responses to suggestion [1,2]. Hypnosis illustrates that the intervention modulates attentional control, which modifies emotions and the nervous system and interacts with past experiences in the subconscious. Suggestions during hypnosis can cause dynamic changes in brain activity [6]. Areas responsible for processing cognition and emotion show greater activity during hypnosis, as well as hypnosis-induced changes in functional connectivity between anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and the large neural network [4,7]. Dynamic changes and connectivity in brain activity occurs not only during suggestion of analgesia but also naturally in the awake state [8].

With various imaging methods, such as EEG (electroencephalography), fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging), fNIRS (near-infrared spectroscopy), PET (positron emission tomography), SPECT (single-photon emission computed tomography) and CT (computer tomography), functional, metabolic and structural information about the brain can be obtained. Using hypnosis, brain activity can be demonstrated using these imaging methods.

The aim of the present study was to perform a systematic review of articles published in the last four decades, investigating the functional changes in brain activity using hypnosis by means of different imaging methods. A broad review of the use of different imaging methods demonstrating plastic brain-activity changes during hypnosis should be provided to gain information for future study designs and to review whether similarities or differences exist regarding medical applications in the literature. The hypothesis of this systematic review is that differences can be observed in functional changes in brain activity when comparing the normal/resting state and the hypnotic state.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Review Design

The review protocol was registered in the international prospective register of systematic reviews, PROSPERO, on 5 July 2021 with ID-CRD42021259187 (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero; last access: 12 January 2022). The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) were adopted throughout the process of the present systematic review [9]. The inclusion and exclusion criteria and research questions were organized following PICOS guidelines [10]:

- Population: Adults of all genders (>18 years)

- Intervention: Medical subject headings (MeSH) terms and keywords related to the topic studied were applied. The Study Quality-assessment tool (https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools; last access: 12 January 2022) of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute was used to rate the quality of the included papers.

- Comparator: Different imaging techniques that show different functional changes in brain activity: computer tomography (CT), electroencephalogram (EEG), electromyogram (EMG), electrooculogram (EOG), functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography (PET), regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) and single-photon emission computer tomography (SPECT).

- Outcome: The quality-control tool of the National Herat, Lung and Blood Institute included criteria about adequate randomization, participation rate, similarity of groups/population and adherence to the intervention protocols, as well as sources of bias (publication bias, eligible persons, exposure measures, blinding, validity, selection bias, information bias, etc.). For each part, yes/no/cannot determine was selected. In the end, each study/paper was scored as good if the study had the least risk for bias, fair if the study was predisposed to some bias and poor if it was possible that the study was biased.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

In this systematic review, randomized controlled trials, cohort, comparative, cross-sectional, evaluation and validation studies reporting brain-activity changes using hypnosis by means of imaging methods such as CT, EEG, EMG, EOG, fMRI, fNIRS, MRI PET, rCBF or SPECT were reviewed. Only human studies published in English from 1 January 1979 to 31 August 2021 were collected and evaluated.

2.3. Information Sources

Electronic databases, such as Cochrane, Embase and MEDLINE via PubMed, were taken into consideration and screened for articles. Grey literature was retrieved via opengrey.eu (http://www.opengrey.eu; last access: 12 January 2022).

2.4. Information Sources and Search Strategy

Several search strategies were applied. The following search string with medical subject headings (MeSH) terms and keywords was used: (hypnosis OR hypnotizability OR hypnotic OR suggestibility OR suggestion OR hypnotic state OR consciousness OR susceptibility OR attention OR mental practice OR cognitive task OR resting state OR intention OR loss of control OR awareness of movements OR autogenetic training OR perception OR paralysis OR inhibition OR emotion OR behaviour OR behavior OR possession trance OR passivity OR regulation of consciousness OR attention) AND (dental phobia OR fear OR dental fear OR pain OR dental pain OR acute pain OR chronic pain OR pain threshold OR dental pain threshold OR perception threshold OR hypnotic focused analgesia) AND (EEG OR electroencephalography OR fMRI OR functional magnetic resonance imaging OR fNIRS OR near infrared spectroscopy OR functional near infrared spectroscopy OR PET OR positron emission tomography OR SPECT OR single photon emission computed tomography OR CT OR computer tomography OR regional cerebral blood flow OR neuroimaging OR structural and functional cerebral correlate OR functional connectivity OR local neuronal activity OR functional brain activity change OR brain activity OR cerebral somatic pain modulation OR brain imaging OR mental imagery OR resting-state functional connectivity OR cerebral hemodynamics OR affective neurofeedback OR feedback effect OR whole-connectivity profile OR voxel based morphometry). Using the bibliographies of full-text articles, cross-referencing was performed. Via opengrey.eu, grey literature was also retrieved.

2.5. Study Selection

After the comparison of the various string research studies with cross-referencing, all duplicates were excluded. Titles and abstracts of all references were read independently by two authors (K.A.F. and T.G.W.). The full texts of articles with titles and abstracts that appeared to fit the eligibility criteria were then assessed by the same authors. References for which the full texts fulfilled the eligibility criteria were included in this systematic review. Any disagreement in the selection process was resolved in a discussion between peers. In the case of continuous controversy, a third author (G.C.) was consulted.

2.6. Data Collection, Summary Measures and Synthesis of Results

For each included reference, data collection and synthesis were carried out by two authors (K.A.F. and T.G.W.). The excluded and included articles are summarized in tables (Supplementary Materials S1–S3). The following data were extracted and input in a table: last name of the first author, country where the study was conducted, age, sex, methods used for evaluation of brain activity under hypnosis with different imagine techniques, and results of the comparison. The data were summarized in different tables to make the synthesis easier.

2.7. Assessment of Bias across Studies

The quality and choice of the included papers were obtained by two authors (K.A.F. and G.C.) according to the respective customized quality-assessment tool generated by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute for controlled intervention studies, systematic reviews and meta-analyses, observational cohort and cross-sectional studies, case-control studies, pre-post studies with no control group and case series studies, as well as the accompanying quality-assessment tool guidance for assessing the quality of controlled intervention studies (https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools; last access: 12 January 2022). Quality control included criteria about adequate randomization, participation rate, similarity of groups/population, adherence to the intervention protocols and sources of bias (publication bias, eligible persons, exposure measures, blinding, validity, selection bias, information bias, etc.). For each part, yes/no/cannot determine was selected. Each study/paper was scored as good if the study had the least risk for bias, fair if the study was predisposed to some bias and poor if it was possible that the study was biased.

3. Results

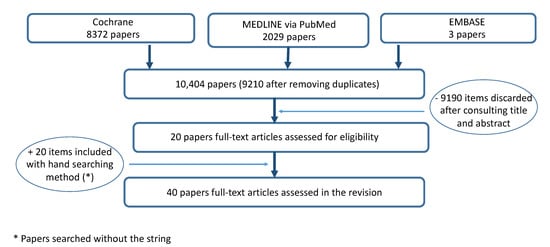

The search identified 10′404 papers; 9210 were selected after removing 1194 duplicates. A total of 9190 studies were discarded after consulting titles and abstracts. A total of 20 articles were assessed for eligibility, and after evaluating the full text, 20 articles were included. A total of 40 papers were included (Figure 1). Quality-assessment scores of the included papers are listed in Supplementary Materials (Table S2, Quality assessment of included papers). Of the 40 included papers, 7 papers were classified as poor, 15 as fair and 18 as good quality (Table 1). A description of data concerning neutral hypnosis and suggestions for analgesia is provided in Table 2. Table 3 illustrates a description of data obtained in hypnotized and non-hypnotized participants.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the search.

Table 1.

Overview of included studies with information on type, imaging method and quality assessment.

Table 2.

Description of data concerning neutral hypnosis and suggestions for analgesia.

Table 3.

Description of data obtained in hypnotized and non-hypnotized participants.

Three studies concerning suggestion for analgesia found similar results for highly hypnotizable subjects, all obtained by the EEG method [22,25,48]. An ERP (event-related potential) study showed that placebo analgesia released higher P200 waves in the frontal left hemisphere and during hypnosis, while placebo analgesia involved activity of the left hemisphere, including the occipital region [48]. Pain reduction is related to larger EMG startle amplitudes and N100 and P200 waves, as well as enhanced activity within frontal, parietal, anterior and posterior cingulate gyres [48]. Highly hypnotizable participants had a larger P200 wave than the low-hypnotizability group [48]. A SERP study found that N2 amplitudes in highly hypnotizable subjects were greater over frontal and temporal scalp sites and displayed a larger N2 peak over temporal sites during focused analgesia [22]. Furthermore, a study examining the relationship between pain perception and EEG responses found significant pain and distress reductions in highly hypnotizable subjects for focused analgesia during hypnosis, which indicates a reduction for focused analgesia during hypnosis and post-hypnosis conditions [25].

Two studies from De Pascalis et al. [16,17] concerning suggestion for analgesia reported EEG results for highly hypnotizable subjects. Both studies found greater amplitudes in highly hypnotizable subjects over the left hemisphere [16,17]. The amplitudes in the left hemisphere were greater than those in the right hemisphere (δ, θ1, θ2, α1, β1 and β2), and during hypnosis/analgesia, highly hypnotizable subjects displayed significant reductions in pain [16]. Highly hypnotizable subjects showed greater θ1 amplitude over the left frontal compared to the right hemisphere and in the posterior areas, as well as more θ1 activity in the left and right frontal areas and in the right posterior area compared to the low-hypnotizability group [17]. Even for α1, more activity was observed in the left hemisphere over the frontal region as well as for α2 (greater over the left-frontal compared to the right-frontal site of the scalp [17].

Four studies obtained similar EEG results, three of which collected data concerning neutral hypnosis [15,21,44]. EEG oscillations of θ activity are positively associated with response to hypnosis [15,21,44,46]. θ power is associated with greater response to hypnotic analgesia and individuals who score high on measures of hypnotizability, which means that hypnotic procedures increase θ power [46]. Even more specific EEG findings showed significantly greater high θ activity for the high-hypnotizability group as compared to the low-hypnotizability group at parietal and occipital sites during both hypnosis and waking relaxation conditions [21]. In relation to low-susceptibility participants, high-susceptibility participants had significantly greater θ power during the hypnotic condition, as well as greater α power [44]. Graffin et al. showed that during hypnosis, high-susceptibility subjects had a significant increase in θ power in the more posterior areas of the cortex, and α activity increased among all sites [15].

Another two studies also used the EEG method, and all their data concerned suggestion for analgesia [30,33]. Highly hypnotizable participants had a significant reduction in phase-ordered γ patterns for focused analgesia during hypnosis [25], and θ activity during hypnosis had a peak in the posterior section of the brain, along with lateral shifting [30]. Brain activity changed under hypnosis from the left to the right hemisphere and from the anterior to the posterior brain segment [30].

Two other findings obtained by EEG, with data concerning neutral hypnosis, found higher α duration/more α activity in highly hypnotizable subjects [11,13], which are in agreement with a study mentioned above that used the same method and collected data concerning neutral hypnosis [44].

In order to chart results that were not obtained with an EEG method but by imaging methods, two studies were considered—one with thulium-YAG event-related fMRI and one with fMRI— and during hypnosis, the same activation for the insula could be determined [35,47]. The thulium-YAG event-related fMRI study showed that different regions were less activated during hypnosis compared to normal wakefulness: brainstem, right primary somatosensory cortex and the left and right insula [35]. In the fMRI study, activity was found in the left amygdala and bilaterally in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), insula and hippocampus under the fear condition [47]. Under hypnosis, all these areas showed reduced activation [47].

Six other studies obtained using imaging methods, such as PET [18,19], fMRI [27,39,43] and MRI [42], concerned neutral hypnosis (except one) [42] and presented similar outcomes. In hypnotized participants, increased activity in the right ACC was noted in all studies, independent of the method [18,19,27,39,42,43].

Another study with fMRI data and concerning neutral hypnosis found reduced activity in the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex during hypnosis [49]. This study also found increased functional connectivity between the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the insula in the salience network during hypnosis, as well as reduced connectivity between the executive control network and the default mode network [49].

In a PET analysis, significant activation could be observed in right-sided extrastriate area and ACC during the hypnotic state [20], while contrary results were observed using event-related fMRI and EEG coherence measures [28]. High-susceptibility subjects showed increased conflict-related neural activity in the ACC under the hypnosis condition [28].

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to ascertain data concerning functional and/or metabolic changes in brain activity using hypnosis by means of different imaging techniques. The most common variables applied in the evaluated papers were high- versus low hypnotizability subjects, as well as hypnosis versus control, and placebo or normal/awake condition.

Owing to the various imaging techniques applied, summarizing the results was demanding. Placebo treatment in waking highly hypnotizable subjects resulted larger P200 waves than in low-hypnotizability groups in EMG, which was associated with pain reduction [49]. Studies examining EEG oscillations of θ activity showed that greater response to hypnosis is associated with reduction in pain, and pain intensity ratings are significantly below pain threshold with exposure to hypnotic analgesia. EEG findings also showed significantly greater θ activity during hypnosis for the high-hypnotizability as compared to low-hypnotizability group at parietal and occipital sites [21]. A recent review not covered in this study also notes that hypnosis is associated more with θ oscillations, while hypnotic response has been shown to be associated with changes in patterns of γ oscillations [51].

Highly hypnotizable subjects displayed significantly lower total and β1 amplitudes in EEG measures, and amplitudes in the left hemisphere were found to be greater than those in the right hemisphere compared to the low-hypnotizabilty group [16]. Highly hypnotizable subjects also showed greater θ1 amplitudes over the left frontal region compared to the right hemisphere and in the posterior areas, as well as more α1 activity in the left hemisphere over the frontal region during waking-rest, hypnosis-rest1 and hypnosis-rest2. Across emotional conditions, highly hypnotizable subjects had a greater α2 amplitude than the low-hypnotizability group, as well as greater α2 activity over the left-frontal compared to the right-frontal site of the scalp [17]. θ power in patterns of EEG activity significantly increased for the baseline and hypnosis groups in the more posterior areas of the cortex, whereas α activity increased across all sites [15]. θ and β1 bands were located more posteriorly in the high- than low-hypnotizabilty group, and the source gravity of the θ frequency band was to the left of the centers of both β bands, and for the low-hypnotizability group, to the right [24]. During hypnosis, highly hypnotizable subjects had significantly greater activity α than the low-hypnotizability group, and their θ activity was greater during hypnosis than the pre-hypnosis condition [44].

In a recent study from Santacangelo et al. [52], it was explained how the molecular effect had an effect in hypnotized participants. Oxytocin can contribute to suggestion-induced analgesia in highly hypnotizable subjects through activation of the endogenous opioid system [52]. In highly susceptible subjects, the oxytocin receptor gene occurs more frequently, so during a hypnosis, the hypnotizability score is higher and oxytocin release will be lower [52].

Thulium-YAG event-related fMRI showed less activity in regions (brainstem, left and right insula, right primary somatosensory cortex) under hypnosis than normal wakefulness and an increased functional connectivity between S1 and distant insular and prefrontal cortices [35]. Highly susceptible subjects displayed higher ACC activation under hypnosis [28]. A functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study found that during hypnosis, there was reduced activity in the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC), increased functional connectivity between the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC; ECN (executive control network)) and the insula in the SN (salience network) and reduced connectivity between the ECN (DLPFC) and the DMN (default mode network and posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) [49]. The largest reduction in pain rating was found in highly hypnotizable subjects during focused analgesia using hypnosis. Somatosensory event-related potentials (SERPs) showed that the N2 amplitude in highly hypnotizable subjects compared to the low-hypnotizability group was greater over frontal and temporal scalp sites than parietal and central sites [22]. High hypnotizable subjects experienced greater pain relief than the low-hypnotizability group in response to hypnosis, and highly hypnotizable subjects also showed significant reductions in somatosensory event-related phase-ordered patterns for focused analgesia during hypnosis [25].

When comparing these results with a recent study from De Souza et al. [53], a justification can be provided as to why the ACC plays a role in hypnosis. GABA concentration in the ACC was positively associated with the hypnotic induction profile in that a higher GABA concentration is associated with greater hypnotizability in individuals [53]. With increasing hypnotizability, a higher GABA concentration could be observed, spanning the same dACC (dorsal anterior cingulate cortex) regions with decreased activity during hypnosis in highly hypnotizable subjects [53]. However, a recent narrative review clarifies that the role of the DLPFC appears to depend on hypnosis and on the type of suggestion given; this is the reason why both activated and reduced activity of the dACC has already been determined [51]. During hypnosis, connectivity between the DLPFC and dACC activation is increased [51].

Positron emission tomography (PET) analysis showed that a hypnotic state induced a significant activation of a right-sided extrastriate area and the anterior cingulate cortex. This activation is related to pain perception and unpleasantness during hypnotic states [20]. Significant increases in PET measures of rCBF (regional cerebral blood flow) during hypnosis were found (left-sided and involved extrastriate visual cortex, inferior parietal lobule, precentral and adjacent promotor cortex and the depth of ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, close to the insular cortex), as well as decreases in rCBF during hypnosis as compared to normal alertness in the left temporal cortex, right temporal cortex, medial prefrontal cortex, posterior cingulate and adjacent precuneus, right promotor cortex and right cerebellar hemisphere [18]. Hypnosis was accompanied by significant increases in rCBF and δ EEG activity. An increase in rCBF subtraction was found in the caudal part of the right anterior cingulate sulcus, the right anterior superior temporal gyrus and the left insula, as well as a decrease associated with hypnosis in the parietal cortex [19]. During hypnosis, dental-phobic subjects showed significantly reduced activation in the left amygdala and bilaterally in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), insula and hippocampus [47].

Our primary aim was to focus on functional brain changes during hypnosis in dental applications. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is a limited number of papers available concerning dental applications [6]. Using dental stimuli in a fMRI trial, main effects for anxiety states were found in the left amygdala and bilaterally in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), insula and hippocampus (R < L) [47]. Under the hypnosis condition, dental-phobic subjects showed significantly reduced activation in all of these areas [47].

It is difficult to generalize the results due to the various imaging techniques employed and the different application areas of hypnosis. Due to the heterogeneity of the studies, the numerous imaging methods employed and the lack of comparability, a more uniform description is recommended in the design of future hypnosis studies investigating brain activity by means of imaging methods. Hypnotizability does not play a role in patient-specific individual hypnosis treatment, but it is used as a criterion in many studies and examined with validated questionnaires. In the future investigation not only of highly hypnotizable but also medium- and low-hypnotizability subjects is recommended in order to provide a better evaluation of the effectiveness of hypnosis on the whole population.

5. Conclusions

- Despite a broad heterogenicity of included studies, evidence of functional changes in brain activity using hypnosis could be determined.

- EMG startle amplitudes indicate higher activity over the frontal brain area; amplitudes using SERP showed similar results.

- EEG oscillations of θ activity are positively associated with response to hypnosis; EEG results showed greater amplitudes for highly hypnotizable subjects over the left hemisphere.

- Less ACC and insula activity was observed during hypnosis.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/brainsci12010108/s1, Table S1: List of excluded papers, Table S2: Quality assessment of included papers, Table S3: PRISMA checklist.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.G.W., G.C. and U.H.; methodology, T.G.W., U.H. and G.C.; formal analysis and data curation, K.A.F. and G.C.; supervision, T.G.W.; validation, U.H. and C.R.; writing—original draft preparation, K.A.F. and T.G.W.; writing—review and editing, C.R., U.H. and G.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Elkins, G.R.; Barabasz, A.F.; Council, J.R.; Spiegel, D. Advancing research and practice: The revised APA Division 30 definition of hypnosis. Am. J. Clin. Hypn. 2015, 57, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revenstorf, D.; Peter, B. Hypnose in Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik und Medizin [Hypnosis in Psychotherapy, Psychosomatics and Medicine]; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Revenstorf, D. Scientific advisory board on psychotherapy. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2012, 109, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halsband, U.; Mueller, S.; Hinterberger, T.; Strickner, S. Plasticity changes in the brain in hypnosis and meditation. Contemp. Hypn. 2009, 26, 194–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainville, P.; Hofbauer, R.K.; Bushnell, M.C.; Duncan, G.H.; Price, D.D. Hypnosis modulates activity in brain structures involved in the regulation of consciousness. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2002, 14, 887–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halsband, U.; Wolf, T.G. Current neuroscientific research database findings of brain activity changes after hypnosis. Am. J. Clin. Hypn. 2021, 63, 372–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faymonville, M.E.; Boly, M.; Laureys, S. Functional neuroanatomy of the hypnotic state. J. Physiol. Paris 2006, 99, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.P.; Adachi, T.; Hakimian, S. Brain oscillations, hypnosis, and hypnotizability. Am. J. Clin. Hypn. 2015, 57, 230–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Deveraux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PloS Med. 2009, 6, e1000100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Guidelines Manual; NICE National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: London, UK, 2012; pp. 1–199.

- London, P.; Hart, J.; Leibovitz, M. EEG alpha rhythms and susceptibility to hypnosis. Nature 1968, 219, 71–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, J.; Engstrom, D.; London, P. Hypnotic susceptibility increased by EEG alpha training. Nature 1970, 227, 1261–1262. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, A.; Macdonald, H.; Hilgard, E. EEG alpha: Lateral asymmetry related to task, and hypnotizablitiy. Psychophysiology 1974, 11, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebecis, A.K.; Provins, K.A.; Farnbach, R.W.; Pentony, P. Hypnosis and the EEG. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1975, 161, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graffin, N.F.; Ray, W.J.; Lundy, R. EEG concomitants of hypnosis and hypnotic susceptibility. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1995, 104, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Pascalis, V.; Perrone, M. EEG asymmetry and heart rate during experience of hypnotic analgesia in high and low hypnotizables. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 1996, 21, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pascalis, V.; Ray, W.J.; Tranquillo, I.; D’Amico, D. EEG activity and heart rate during recall of emotional events in hypnosis: Relationships with hypnotizability and suggestibility. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 1998, 29, 255–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maquet, P.; Faymonville, M.; Degueldre, C.; Delfiore, G.; Franck, G.; Luxen, A.; Lamy, M. Functional neuroanatomy of hypnotic state. Biol. Psychiatry 1999, 45, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainville, P.; Hofbauer, R.; Paus, T.; Duncan, G.; Bushnell, M.; Price, D. Cerebral mechanisms of hypnotic induction and suggestion. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 1999, 11, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faymonville, M.E.; Laureys, S.; Degueldre, C.; Del Fiore, G.; Luxen, A.; Franck, G.; Lamy, M.; Maquet, P. Neural mechanisms of antinociceptive effects of hypnosis. Anesthesiology 2000, 92, 1257–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, R.; Barabasz, A.; Barabasz, M.; Warner, D. Hypnosis and distraction differ in their effects on cold pressor pain. Am. J. Clin. Hypn. 2000, 43, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pascalis, V.; Magurano, M.; Bellusci, A.; Chen, A. Somatosensory event-related potential and autonomic activity to varying pain reduction cognitive strategies in hypnosis. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2001, 112, 1475–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, M.; Trippe, R.; Özcan, M.; Weiss, T.; Hecht, H.; Miltner, W. Laser-evoked potentials to noxious stimulation during hypnotic analgesia and distraction of attention suggest different brain mechanisms of pain control. Psychophysiology 2001, 38, 768–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isotani, T.; Lehmann, D.; Pascual-Marqui, R.; Kochi, K.; Wackermann, J.; Saito, N.; Yagyu, T.; Kinoshita, T.; Sasada, K. EEG source localization and global dimensional complexity in high- and low- hypnotizable subjects: A pilot study. Neuropsychobiology 2001, 44, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pascalis, V.; Cacace, I.; Massicolle, F. Perception and modulation of pain in waking and hypnosis: Functional significance of phase-gamma oscillations. Pain 2004, 112, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harandi, A.; Esfandani, A.; Shakibaei, F. The effect of hypnotherapy on procedural pain and state anxiety related to physiotherapy in women hospitalized in a burn out. Contemp. Hypn. 2004, 21, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wager, T.; Rilling, J.; Smith, E.; Sokolik, A.; Casey, K.; Davidson, R.; Kosslyn, S.; Rose, R.; Cohen, J. Placebo-induced changes in fMRI in the anticipation and experience of pain. Science 2004, 303, 1162–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egner, T.; Jamieson, G.; Gruzelier, J. Hypnosis decouples cognitive control from conflict monitoring processes of the frontal lobe. NeuroImage 2005, 27, 969–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batty, M.; Bonnington, S.; Tang, B.K.; Hawken, M.; Gruzelier, J. Relaxation strategies and enhancement of hypnotic susceptibility: EEG neurofeedback, progressive muscle relaxation and self-hypnosis. Brain Res. Bull. 2006, 71, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eitner, S.; Wichmann, M.; Schultze-Mosgau, S.; Schlegel, A.; Lehrer, A.; Heckmann, J.; Heckmann, S.; Holst, S. Neurophysiologic and long-term effects of clinical hypnosis in oral and maxillofacial treatment—A comparative interdisciplinary clinical study. Int. J. Clin Exp. Hypn. 2006, 54, 457–479. [Google Scholar]

- Saadat, H.; Drummond-Lewis, J.; Marantes, I.; Kaplan, D.; Saadat, A.; Wang, S.M.; Kain, Z. Hypnosis reduces preoperative anxiety in adult patients. Anesth. Analg. 2006, 102, 1394–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milling, L.; Shores, J.; Coursen, E.; Menario, D.; Farris, C. Response expectancies, treatment credibility, and hypnotic suggestibility: Mediator and moderator effects in hypnotic and cognitive-behavioral pain interventions. Ann. Behav. Med. 2007, 33, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pascalis, V.; Cacace, I.; Massicolle, F. Focused analgesia in waking and hypnosis: Effects on pain, memory, and somatosensory event-related potentials. Pain 2008, 134, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marc, I.; Rainville, P.; Masse, B.; Dufresne, A.; Verreault, R.; Vaillancourt, L.; Dodin, S. Women’s views regarding hypnosis for the control of surgical pain in the context of a randomized clinical trial. J. Womens Health 2009, 18, 1441–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanhaudenhuyse, A.; Boly, M.; Baltea, E.; Schnakers, C.; Moonen, G.; Luxen, A.; Lamy, M.; Degueldre, C.; Brichant, J.F.; Maquet, P.; et al. Pain and non-pain processing during hypnosis: A thulium-YAG event-related fMRI study. NeuroImage 2009, 47, 1047–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krummenacher, P.; Candia, V.; Folkers, G. Prefrontal cortex modulates placebo analgesia. Pain 2010, 148, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miltner, W.; Trippe, R.; Hecht, H.; Weiss, T. Hypnotic analgesia as a consequence of abandoned cortical communication. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2010, 77, 206–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockardt, J.; Reeves, S.; Frohman, H.; Madan, A.; Jensen, M.; Patterson, D.; Barth, K.; Smith, A.; Gracely, R.; George, M. Fast left prefrontal rTMS acutely suppresses analgesic effects of perceived controllability on the emotional component of pain experience. Pain 2011, 152, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyka, M.; Burgmer, M.; Lenzen, T.; Pioch, R.; Dannlowski, U.; Pfleiderer, B.; Ewert, A.W.; Heuft, G.; Arolt, V.; Konrad, C. Brain correlates of hypnotic paralysis—A resting state fMRI study. NeuroImage 2011, 56, 2173–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terhune, D.; Cardena, E.; Lindgren, M. Differential frontal-parietal phase synchrony during hypnosis as a function of hypnotic suggestibility. Psychophysiology 2011, 48, 1444–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeidan, F.; Martucci, K.; Kraft, R.; Gordon, N.; McHaffie, J.; Coghill, R. Brain mechanisms supporting the modulation of pain by mindfulness meditation. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 5540–5548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, N.; Sprenger, C.; Scholz, J.; Wiech, K.; Bingel, U. White matter integrity of the descending pain modulatory system is associated with interindividual differences in placebo analgesia. Pain 2012, 153, 2210–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilbert, K.; Evens, R.; Maslowski, N.I.; Wittchen, H.U.; Lueken, U. Fear processing in dental phobia during crossmodal symptom provocation: An fMRI study. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 196353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, J.D.; Gruzelier, J.H. Differentiation of hypnosis and relaxation by analysis of narrow band theta and alpha frequencies. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Hypn. 2013, 49, 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufresne, A.; Rainville, P.; Dodin, S.; Barré, P.; Masse, B.; Verreault, R.; Marc, I. Hypnotizability and opinions about hypnosis in a clinical trial for the hypnotic control of pain and anxiety during pregnancy termination. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Hypn. 2014, 58, 82–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.; Sherlin, L.; Fregni, F.; Gianas, A.; Howe, J.D.; Hakimian, S. Baseline brain activity predicts response to neuromodulatory pain treatment. Pain Med. 2014, 15, 2055–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halsband, U.; Wolf, T.G. Functional changes in brain activity after hypnosis in patients with dental phobia. J. Physiol. Paris 2015, 109, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Pascalis, V.; Scacchia, P. Hypnotizability and placebo analgesia in waking and hypnosis as modulators of auditory ttartle responses in healthy women: An ERP study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Jiang, H.; White, M.P.; Greicius, M.D.; Waelde, L.C.; Spiegel, D. Brain activity and functional connectivity associated with hypnosis. Cereb. Cortex 2017, 27, 4083–4093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.M.; Ehde, D.M.; Day, M.; Turner, A.P.; Hakimian, S.; Gertz, K.; Ciol, M.; McCall, A.; Kincaid, C.; Petter, M.W.; et al. The chronic pain skills study: Protocol for a randomized controlled trial comparing hypnosis, mindfulness meditation and pain education in Veterans. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2020, 90, 105935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Benedittis, G. Neural mechanisms of hypnosis and meditation-induced analgesia: A narrative review. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Hypn. 2021, 69, 363–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santarcangelo, E.L.; Carli, G. Individual traits and pain treatment: The case of hypnotizability. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 683045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSouza, D.D.; Stimpson, K.H.; Baltusis, L.; Sacchet, M.D.; Gu, M.; Hurd, R.; Wu, H.; Yeomans, D.C.; Williams, N.; Spiegel, D. Association between anterior cingulate neurochemical concentration and individual differences in hypnotizability. Cereb. Cortex 2020, 30, 3644–3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).