Opioid Antagonist in the Treatment of Ischemic Stroke

Abstract

1. Introduction

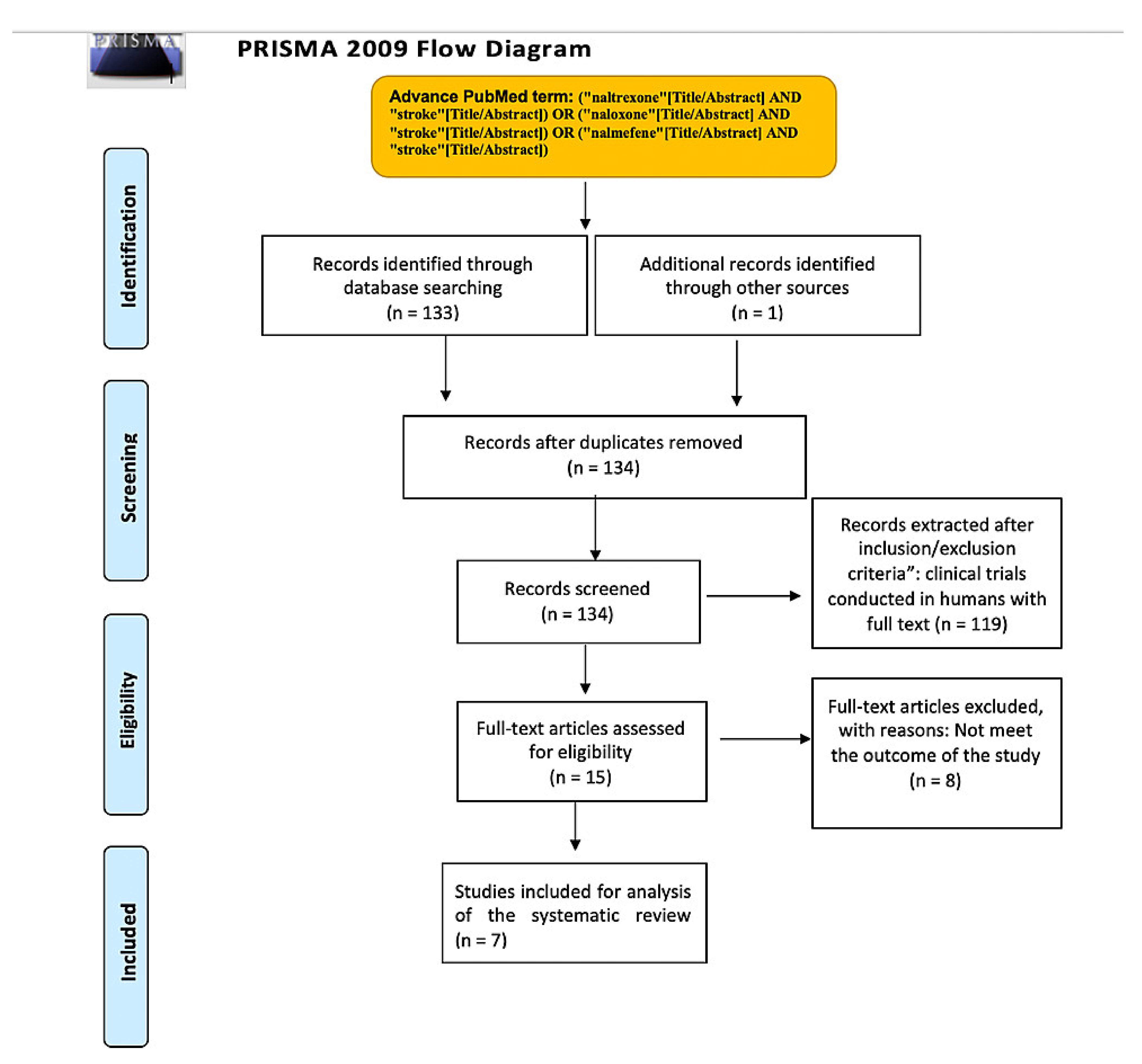

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol

2.1.1. Eligibility Criteria and Study Selection

2.1.2. Database and Search Strategy

2.1.3. Data Extraction and Analysis

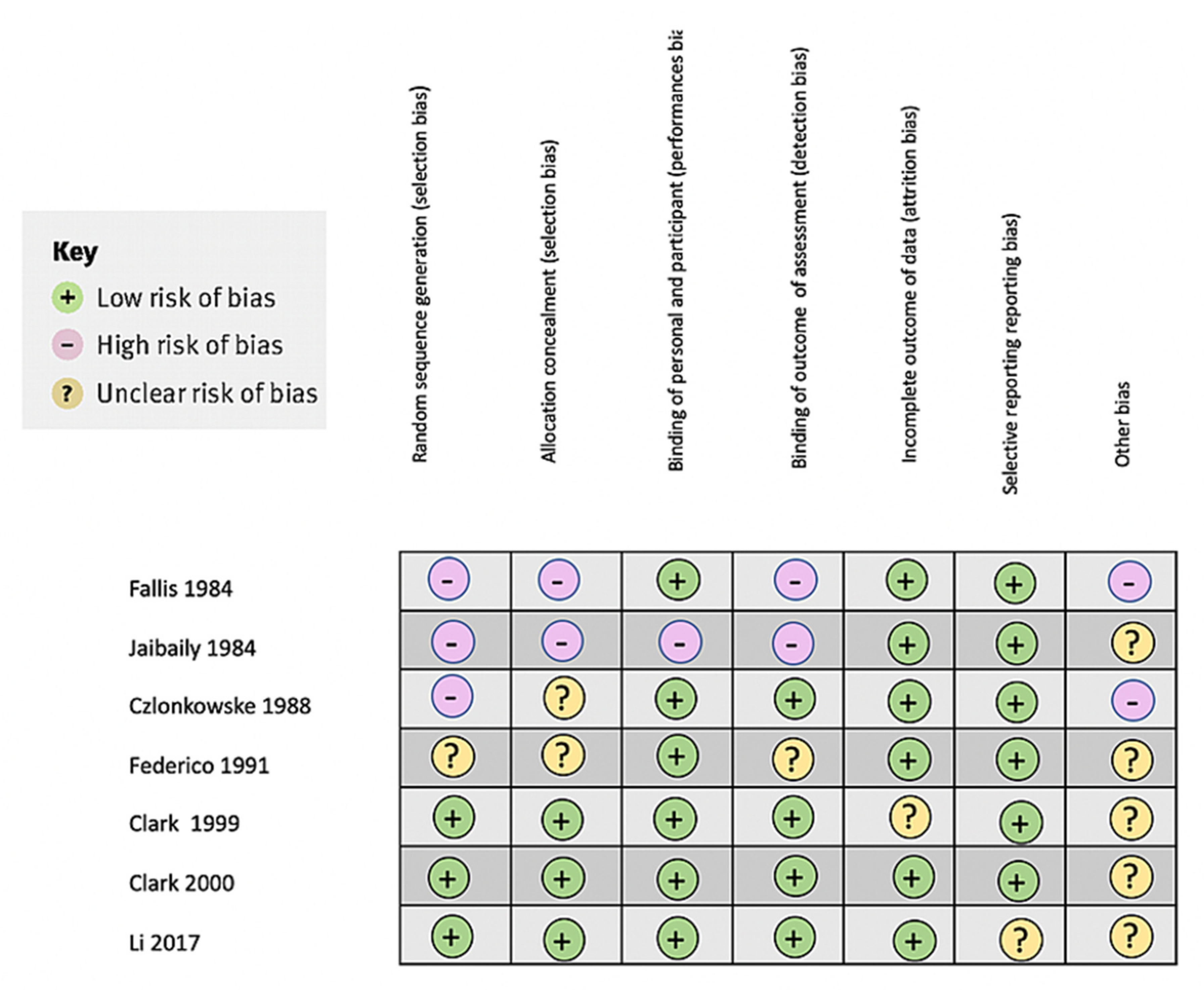

2.1.4. Bias Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Study Limitations

4. Discussion

4.1. Naloxone Clinical Trials

4.2. Nalmefene Clinical Trials

4.3. In Vitro Studies and Aniaml Stuies

4.4. New Directions for the Anti-Opioid Medication Treatment of Ischemic Stroke

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Peyravian, N.; Dikici, E.; Deo, S.; Toborek, M.; Daunert, S. Opioid antagonists as potential therapeutics for ischemic stroke. Prog. Neurobiol. 2019, 182, 101679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czlonkowska, A.; Cyrta, B. Effect of naloxone on acute stroke. Pharmacopsychiatry 1988, 21, 98–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.W.; Muo, C.H.; Liang, J.A.; Sung, F.C.; Kao, C.H. Association of intensive morphine treatment and increased stroke incidence in prostate cancer patients: A population-based nested case-control study. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 43, 776–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moqaddam, A.H.; Musavi, S.M.R.A.; Khademizadeh, K. Relationship of Opium Dependency and Stroke. Addict. Health 2009, 1, 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi, W.T.; O’Neal, W.T.; Khodneva, Y.; Judd, S.; Safford, M.M.; Muntner, P.; Soliman, E.Z. Association Between Opioid Use and Atrial Fibrillation: The Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) Study. JAMA Intern. Med. 2015, 175, 1058–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Fallis, R.J.; Fisher, M.; Lobo, R.A. A double blind trial of naloxone in the treatment of acute stroke. Stroke 1984, 15, 627–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Jüni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savović, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federico, F.; Lucivero, V.; Lamberti, P.; Fiore, A.; Conte, C. A double blind randomized pilot trial of naloxone in the treatment of acute ischemic stroke. Ital. J. Neurol. Sci. 1991, 12, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabaily, J.; Davis, J.N. Naloxone administration to patients with acute stroke. Stroke 1984, 15, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, W.; Ertag, W.; Orecchio, E.; Raps, E. Cervene in acute ischemic stroke: Results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-comparison study. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 1999, 8, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, W.M.; Raps, E.C.; Tong, D.C.; Kelly, R.E. Cervene (Nalmefene) in acute ischemic stroke: Final results of a phase III efficacy study. The Cervene Stroke Study Investigators. Stroke 2000, 31, 1234–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hou, W.C.; Song, L. Nalmefene improves prognosis in patients with a large cerebral infarction: Study protocol and preliminary results of a randomized, controlled, prospective trial. Clin. Trials Degener. Dis. 2017, 2, 101–107. [Google Scholar]

- Endoh, H.; Honda, T.; Ohashi, S.; Shimoji, K. Naloxone improves arterial blood pressure and hypoxic ventilatory depression, but not survival, of rats during acute hypoxia. Crit. Care Med. 2001, 29, 623–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Xi, C.; Liang, X.; Ma, J.; Su, D.; Abel, T.; Liu, R. The Role of κ Opioid Receptor in Brain Ischemia. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 44, e1219–e1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Sun, Z.J.; Wu, J.L.; Quan, W.Q.; Xiao, W.D.; Chew, H.; Jiang, C.M.; Li, D. Naloxone attenuates ischemic brain injury in rats through suppressing the NIK/IKKα/NF-κB and neuronal apoptotic pathways. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2019, 40, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anttila, J.E.; Albert, K.; Wires, E.S.; Mätlik, K.; Loram, L.C.; Watkins, L.R.; Rice, K.C.; Wang, Y.; Harvey, B.K.; Airavaara, M. Post-stroke Intranasal (+)-Naloxone Delivery Reduces Microglial Activation and Improves Behavioral Recovery from Ischemic Injury. eNeuro 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, Y.Y.; Jong, Y.J.; Lin, Y.T.; Tseng, Y.T.; Hsu, S.H.; Lo, Y.C. Nanomolar naloxone attenuates neurotoxicity induced by oxidative stress and survival motor neuron protein deficiency. Neurotox. Res. 2014, 25, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grace, P.M.; Shimizu, K.; Strand, K.A.; Rice, K.C.; Deng, G.; Watkins, L.R.; Herson, P.S. (+)-Naltrexone is neuroprotective and promotes alternative activation in the mouse hippocampus after cardiac arrest/cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Brain Behav. Immun. 2015, 48, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzdensky, A.B. Apoptosis regulation in the penumbra after ischemic stroke: Expression of pro- and antiapoptotic proteins. Apoptosis 2019, 24, 687–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Alebeek, M.E.; Arntz, R.M.; Ekker, M.S.; Synhaeve, N.E.; Maaijwee, N.A.; Schoonderwaldt, H.; van der Vlugt, M.J.; van Dijk, E.J.; Rutten-Jacobs, L.C.; de Leeuw, F.E. Risk factors and mechanisms of stroke in young adults: The FUTURE study. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2018, 38, 1631–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author and Year of Publication | Country | Study Design | No. of pts. in the Treatment Group | No. of pts. in the Control Group | Patient Selection | Dose, Duration, Route, of Administration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fallis et al. (1984) [6] | United States | Double-blind clinical trial | 15 | 0 | Stroke patients with deficits for 8–60 h. | Naloxone injection with normal saline. The first three patients received 0.4 mg, and the remaining patients received 4.0 mg. |

| Federico et al. (1991) [9] | Italy | Double- blind clinical trial, pilot study | 12 | 12 | Subjects under 80 years old, within 12 h of the onset of symptoms, not in coma, and having a negative CT scan for a previous hemorrhage, ischemic, and infarct. | Naloxone 5 mL/kg diluted in 100 mL of normal saline, injected over 10 min. A 24-h continuous infusion of 3.5 mg/kg of naloxone diluted in 100 mL of saline. |

| Czlonkowske et al. (1988) [2] | Poland | Double- blind clinical trial | 24 | 20 | Patients that could receive treatment within 24 h of the ischemic infarct. | 2 mL of saline followed by 0.4 mg of naloxone every 10 min for 30 min. In the control group, naloxone was replaced by saline. |

| Jabaily et al. (1984) [10] | United States | Single-blind clinical trial | 13 | Not given | Patients who suffered a stroke from 3–24 h. | 2 mL of IV saline, then two or three ampules of naloxone from 0.8 to 1.2 mg at 10-min intervals. |

| Clark et al. (1999) [11] | United States | Double- blind, multicenter clinical trial | 79 with 6 mg, 77 with 20 mg, and 81 with 60 mg. | 75 | Patients within 6 h of having an ischemic stroke. | Patients receive either 6 mg, 20 mg, or 60 mg of nalmefene over 24 h. 50 mL over a bolus in 15 min and 500 mL for 23.75 h. |

| Clark et al. (2000) [12] | United States | Double- blind, multicenter clinical trial | 186 | 182 | Patients within 6 h of having an ischemic stroke. | Patients receive 60 mg of nalmefene with a 10 mg bolis in 15 min. Later they receive 50 mg of infusion over 23.75 h. The control group received a placebo. |

| Li et al. (2017) [13] | China | Randomized controlled prospective clinical trial | 120 | 116 | Patients with symptoms within 3 days of the stroke. | 10 days of nalmefene injection: 0.2 mg of nalmefene hydrochloride dissolved in 10 mL/0.9% sodium chloride. |

| Author, Year | Drug | Outcome | Results of Treatment Group | Results of Control or Placebo Group | Main Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fallis et al. (1984) [6] | Naloxone | NFS and B-endorphin levels (post-treatment) | NFS before naloxone: 34.4 ± 8.4 and 34.1 ± 8.9 post naloxone. B-endorphin levels: 9.6 ± 5.3 | NFS before saline: 34 ± 8.2 and 34.6 ± 8.7 post saline. B-endorphin levels: 10.9 ± 9.8 | Naloxone did not reverse neurological deficits. Plasma endorphin levels were not statistically significant. |

| Federico et al. (1991) [9] | Naloxone | CNE and BI | CNE: 5.6 ± 2; BI: 50.4 ± 11 | CNE: 5.8 ± 2; BI: 49.5 ± 11 | No statistical difference between both groups. |

| Czlonkowske et al. (1988) [2] | Naloxone | NSS | NSS: before naloxone: 61.50 ± 20 and after 2 weeks 75.46 ± 16.23 | NSS: before saline: 76.65. ± 11.13 and after two weeks 82.10 ± 18.01 | Highly statistical improvement p < 0.01. between treatment group and control. |

| Jabaily et al. (1984) [10] | Naloxone | Improvement of neurological deficits | 3 out of 13 patients improved their neurological status. | No control group | 3 of 13 patients improve their neurological deficits after 24 h. |

| Clark et al. (1999) [11] | Nalmefene | GOS + BI success, BI success, GOS success at three months | GOS + BI success (%): 84.8, 81.5, and 76.5 at 6 mg, 20 mg and 60 mg respectively. | GOS + BI success: 64.7 | No significant difference was found. However, a clear tendency was seen in patients under 70 years. |

| BI success (%): 88, 92,6, and 79.4 at 6 mg, 20 mg and 60 mg respectively. | BI success (%): 64.7 | ||||

| GOS success (%): 84.8, 81,5, 81,8 at 6 mg, 20 mg and 60 mg respectively. | GOS success (%): 67.6 | ||||

| Clark et al. (2000) [12] | Nalmefene | GOS, BI, and NIHHS at three months | GOS + BI success: 66.9 | GOS + BI success: 62.3 | No significant difference was found. The tendency of patients under 70 years was again favorable, but again was not statically significant. |

| BI success (%): 66.9 | BI success (%): 64.1 | ||||

| GOS success (%): 68.1 | GOS success (%): 62.9 | ||||

| NIHSS success (%): 36,2 | NIHSS success (%): 32.9 | ||||

| Mortality (%): 16 | Mortality (%):15.6 | ||||

| Li et al. (2017) [13] | Nalmefene | NIHSS at 20 days, Glasgow Coma Scale at 0 and 10 days, matrix metalloproteinase-9 at 0.5 and 10 days, and magnetic resonance imaging perfusion at 0 and 10 days. | NIHSS: 22 ± 4 on day 0 and 17 ± 5 after 20 days | NIHSS 23 ± 4 on day 0 and 20 ± 5 after 20 days | In the treatment group, the NIHSS was decreased, the Glasgow Coma Scale was increased, matrix metalloproteinase-9 was decreased, and magnetic resonance imaging perfusion was increased compared to the treatment group with statistically significant results in all parameters. |

| GOS: 7.2 ± 2.5 on day 0 and 9.5 ± 2.9 after 10 days | GOS: 7.1 ± 1.9 on day 0 and 8.1 ± 1.7 after 10 days | ||||

| matrix metalloproteinase-9: 179 ± 76 at day 0 and 178 ± 56 at 10 days | matrix metalloproteinase-9: 189 ± 64 at day 0 and 210 ± 60 at 10 days | ||||

| Cerebral blood flow mL/100 g/min: 43 ± 4 at day 0 67 ± 6 after 10 days | Cerebral blood flow mL/100 g/min: 40 ± 4 at day 0 59 ± 4 after 10 days |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ortiz, J.F.; Cruz, C.; Patel, A.; Khurana, M.; Eissa-Garcés, A.; Alzamora, I.M.; Halan, T.; Altamimi, A.; Ruxmohan, S.; Patel, U.K. Opioid Antagonist in the Treatment of Ischemic Stroke. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 805. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11060805

Ortiz JF, Cruz C, Patel A, Khurana M, Eissa-Garcés A, Alzamora IM, Halan T, Altamimi A, Ruxmohan S, Patel UK. Opioid Antagonist in the Treatment of Ischemic Stroke. Brain Sciences. 2021; 11(6):805. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11060805

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrtiz, Juan Fernando, Claudio Cruz, Amrapali Patel, Mahika Khurana, Ahmed Eissa-Garcés, Ivan Mateo Alzamora, Taras Halan, Abbas Altamimi, Samir Ruxmohan, and Urvish K. Patel. 2021. "Opioid Antagonist in the Treatment of Ischemic Stroke" Brain Sciences 11, no. 6: 805. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11060805

APA StyleOrtiz, J. F., Cruz, C., Patel, A., Khurana, M., Eissa-Garcés, A., Alzamora, I. M., Halan, T., Altamimi, A., Ruxmohan, S., & Patel, U. K. (2021). Opioid Antagonist in the Treatment of Ischemic Stroke. Brain Sciences, 11(6), 805. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11060805