Physiological Reactions in the Therapist and Turn-Taking during Online Psychotherapy with Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Instruments

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

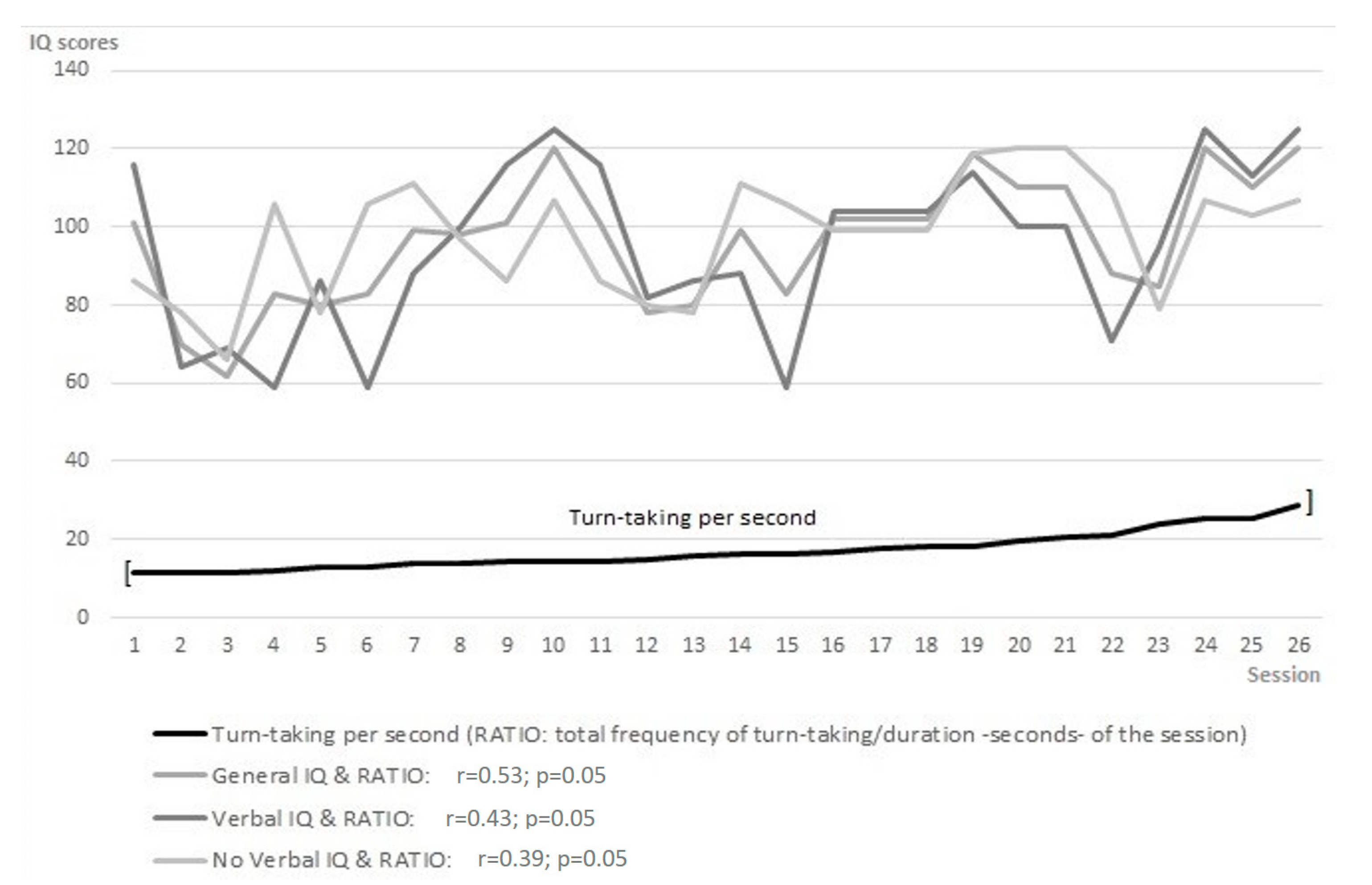

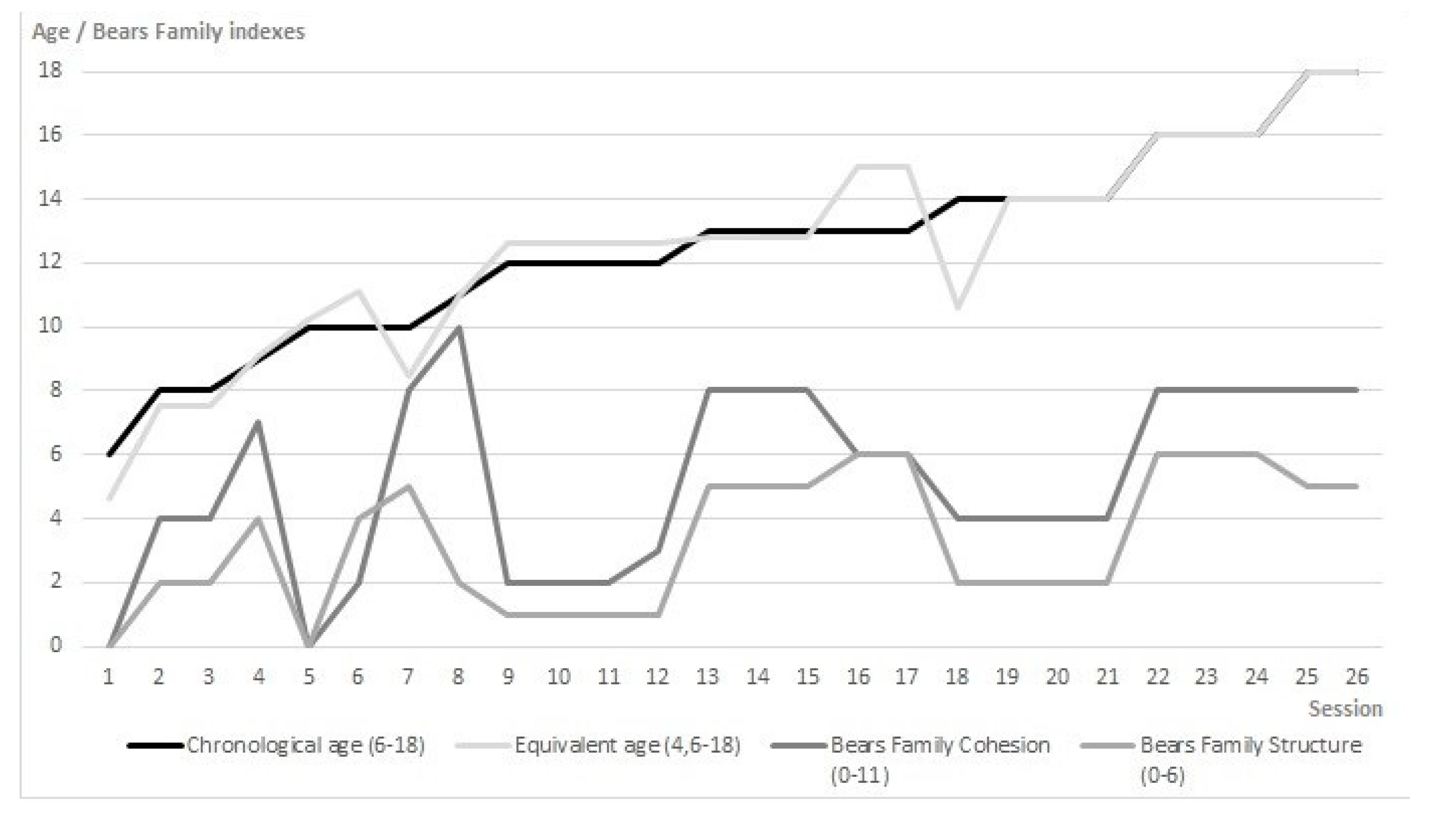

3.1. Changes in Turn-Taking per Second, Participants’ Intelligence, Age, Narrative, and Social Skills

3.2. Participants’ Difficulties and Turn-Taking with the Therapist

3.3. Therapist’s Heart Rate Variability (HRV) and Patient’s Turn-Taking Synchrony

4. Discussion

4.1. Changes in Turn-Taking per Second, Participants’ Intelligence, Age, Narrative, and Social Skills

4.2. Participants’ Difficulties and Turn-Taking with the Therapist

4.3. Therapist’s Heart Rate Variability (HRV) and Patient’s Turn-Taking Synchrony

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reda, M. Sistemi Cognitivi Complessi e Psicoterapia; La Nuova Italia Scientifica: Roma, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Canestri, L.; della Lunga, S.D.; Reda, M.A. Correlaciones psicofisiológicas durante una sesión standard de psicoterapia entre paciente y terapeuta: Observaciones preliminares. Rev. Argent. Clin. Psicol. 2010, 19, 183–187. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth, M.D.S.; Bell, S.M.; Stayton, D.F. Infant-mother attachment and social development: Socialization as a product of reciprocal responsiveness to signals. In The Integration of a Child into a Social World; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1974; pp. 99–135. ISBN 0521203066. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky, J.; Rovine, M.; Taylor, D.G. The Pennsylvania Infant and Family Development Project, III: The origins of individual differences in infant-mother attachment: Maternal and infant contributions. Child Dev. 1984, 55, 718–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tronick, E.D.; Als, H.; Brazelton, T.B. Mutuality in Mother-Infant Interaction. J. Commun. 1977, 27, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maccoby, E.E.; Martin, J. Socialization in the Context of the Family: Parent-Child Interaction. In Handbook of Child Psychology: {Vol}.~4. {Socialization}, Personality, and Social Development; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1983; pp. 1–101. [Google Scholar]

- Leclère, C.; Viaux, S.; Avril, M.; Achard, C.; Chetouani, M.; Missonnier, S.; Cohen, D. Why synchrony matters during mother-child interactions: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e113571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venuti, P.; Bentenuto, A.; Cainelli, S.; Landi, I.; Suvini, F.; Tancredi, R.; Igliozzi, R.; Muratori, F. A joint behavioral and emotive analysis of synchrony in music therapy of children with autism spectrum disorders. Health Psychol. Rep. 2017, 2, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reda, M.; Mahoney, M. Cognitive Psychotherapies; Ballinger: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Black, B.; Logan, A. Links between Communication Patterns in Mother-Child, Father-Child, and Child-Peer Interactions and Children’s Social Status. Child Dev. 1995, 66, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, P.M.; Hall, S.E.; Radzioch, A.M. Emotional dysregulation and the development of serious misconduct. In Biopsychosocial Regulatory Processes in the Development of Childhood Behavioral Problems; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009; pp. 186–211. ISBN 9780511575877. [Google Scholar]

- Harrist, A.W.; Waugh, R.M. Dyadic synchrony: Its structure and function in children’s development. Dev. Rev. 2002, 22, 555–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adolph, K.E.; Berger, S.E.; Borstein, M.H.; Lamb, M.E. Developmental Science: An Advanced Textbook; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, R. Parent-infant synchrony: Biological foundations and developmental outcomes. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 16, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D. The developmental being. Modeling a probabilistic approach to child development and psychopathology. Neuropsychiatr. Enfance Adolesc. 2012, 60, S25–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, G.; Bizzego, A.; Cainelli, S.; Furlanello, C.; Venuti, P. M-MS: A Multi-Modal Synchrony Dataset to Explore Dyadic Interaction in ASD. In Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; Volume 184, pp. 543–553. [Google Scholar]

- Reda, M. Un approccio post-razionalista alla relazione in psicoterapia [A post-rationalist approach to the relationship in psychotherapy]. Quad. Psicoter. Cogn. 2006, 19, 36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Trevarthen, C. Conversations with a two-month-old. In Parent-Infant Psychodynamics: Wild Things, Mirrors and Ghosts; Taylor and Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 25–34. ISBN 9780429902925. [Google Scholar]

- Trevarthen, C.; Aitken, K.J. Infant Intersubjectivity: Research, Theory, and Clinical Applications. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2001, 42, 3–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hougaard, E. The therapeutic alliance–A conceptual analysis. Scand. J. Psychol. 1994, 35, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mundy, P.; Sigman, M. Specifying the nature of the social impairment in autism. In Autism: New Perspectives on Diagnosis, Nature, and Treatment; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 1989; pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hobson, R.P. What is autism? Psychiatr. Clin. 1991, 14, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BOSA, C.A. As relações entre autismo, comportamento social e função executiva [The relationships between autism, social behavior and executive function]. Psicol. Reflexão Crítica 2001, 14, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosa, C. Atenção compartilhada e identificação precoce do autismo [Shared attention and early identification of autism]. Psicol. Reflexão Crítica 2002, 15, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyra, M.C. Desenvolvimento de um sistema de relações historicamente construído: Contribuições da comunicação no início da vida [Development of a historically constructed system of relationships: Contributions of communication in early life]. Psicol. Reflexão Crítica 2000, 13, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantoja, A.P.F.; Nelson-Goens, G.C. Desenvolvimento da vida emocional durante o segundo ano de vida: Narrativas e sistemas dinâmicos [Development of emotional life during the second year of life: Narratives and dynamic systems]. Psicol. Reflexão Crítica 2000, 13, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, J.H.; Goodman, J.J. Social turn-taking of children with neuropsychiatric impairments and their parents. Compr. Child Adolesc. Nurs. 1996, 19, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhari, A.; Leck, W.Q.; Gabrieli, G.; Bizzego, A.; Rigo, P.; Setoh, P.; Bornstein, M.H.; Esposito, G. Parenting Stress Undermines Mother-Child Brain-to-Brain Synchrony: A Hyperscanning Study. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, E.G.; Levin, L.; McConnachie, G.; Carlson, J.I.; Kemp, D.C.; Smith, C.E. Communication-Based Intervention for Problem Behavior; Paul H Brookes Publishing: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Molini, D.; Fernandes, F. Intenção comunicativa e uso de instrumentos em crianças com distúrbios psiquiátricos. Pró-Fono R. Atual. Cient 2003, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamarit, J.; De Dios, J.; Dominguez, S.; Escribano, L. Conductas desafiantes y autismo: Un analisis contextualizado. In La Atención a Alumnos con Necesidades Educativas Graves y Permanentes; Gobierno de Navarra: Pamplona, Spain, 1995; Volume 5, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Pennington, B.F.; Ozonoff, S. Executive functions and developmental psychopathology. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 1996, 37, 51–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beisler, J.M.; Tsai, L.Y. A pragmatic approach to increase expressive language skills in young autistic children. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 1983, 13, 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artigas, J. Language in autistic disorders. Rev. Neurol. 1999, 28, 118–123. [Google Scholar]

- Monfort, I. Communicatión y lenguaje: Bidireccionalidad en la interventión en niños con trastorno de espectro autista [Communication and language: Bidirectionality in intervention in children with autism spectrum disorder]. Rev. Neurol. 2009, 48, 53–56. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Flagge, N. Trastornos del lenguaje. Diagnóstico y tratamiento [Language disorders Diagnosis and treatment]. Rev. Neurol. 2013, 57, S85–S94. [Google Scholar]

- Golinkoff, R.M.; Can, D.D.; Soderstrom, M.; Hirsh-Pasek, K. (Baby)Talk to Me: The Social Context of Infant-Directed Speech and Its Effects on Early Language Acquisition. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 24, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, F.D.M. Sugestões de Procedimentos Terapêuticos de Linguagem em Distúrbios do Espectro Autístico [Suggestions for Therapeutic Language Procedures in Autistic Spectrum Disorders]; LIMONGI, S. C. O. (Org.); Guanabara-Koogan: Barueri, Brazil, 2003; pp. 55–65. [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo, M.; Jordán, C. Psicoterapia a través de internet: Recursos tecnológicos en la práctica de la psicoterapia [Psychotherapy through the Internet: Technological resources in the practice of psychotherapy]. Boletín Psicol. 2007, 91, 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Suler, J. The online disinhibition effect. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2004, 7, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suler, J.R. Psychotherapy in cyberspace: A 5-dimensional model of online and computer-mediated psychotherapy. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2000, 3, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association, A.P. American Psychiatric Association. In Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; ISBN 9780890425541. [Google Scholar]

- Wing, L. Language, social, and cognitive impairments in autism and severe mental retardation. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 1981, 11, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wing, L. The Autistic Spectrum; Revised Edition; Hachette: New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 9781472103895. [Google Scholar]

- García Peñas, J.J.; Domínguez Carral, J.; Pereira Bezanilla, E. Alteraciones de la sinaptogénesis en el autismo. Implicaciones etiopatogénicas y terapéuticas [Synaptogenesis disorders in autism. Aetiopathogenic and therapeutic implications]. Rev. Neurol. 2012, 54, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Ermer, J.; Dunn, W. The Sensory Profile: A Discriminant Analysis of Children with and Without Disabilities. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 1998, 52, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Watling, R.L.; Deitz, J.; White, O. Comparison of sensory profile scores of young children with and without autism spectrum disorders. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2001, 55, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, S.; Lane, S.J. Diagnostic validity of sensory over-responsivity: A review of the literature and case reports. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2008, 38, 516–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, N.B.; Dunn, W. Relationship between context and sensory processing in children with autism. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2010, 64, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Happé, F.; Frith, U. The weak coherence account: Detail-focused cognitive style in autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2006, 36, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumsey, J.M.; Creasey, H.; Stepanek, J.S.; Dorwart, R.; Patronas, N.; Hamburger, S.D.; Duara, R. Hemispheric asymmetries, fourth ventricular size, and cerebellar morphology in autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 1988, 18, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C.; Russell, J.; Robbins, T.W. Evidence for executive dysfunction in autism. Neuropsychologia 1994, 32, 477–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozonoff, S. Components of executive function in autism and other disorders. In Autism as an Executive Disorder; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 179–211. ISBN 0198523491. [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Leslie, A.M.; Frith, U. Mechanical, behavioural and Intentional understanding of picture stories in autistic children. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 1986, 4, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Ring, H.A.; Wheelwright, S.; Bullmore, E.T.; Brammer, M.J.; Simmons, A.; Williams, S.C.R. Social intelligence in the normal and autistic brain: An fMRI study. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1999, 11, 1891–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, A.M.; Frith, U. Autistic children’s understanding of seeing, knowing and believing. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 1988, 6, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perner, J.; Frith, U.; Leslie, A.M.; Leekam, S.R. Exploration of the autistic child’s theory of mind: Knowledge, belief, and communication. Child Dev. 1989, 60, 688–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruner, J.; Weisser, S. The Invention of Self: Autobiography and Its Forms; Literacy and Orality; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Guidano, V. Complexity of the Self: A developmental Approach to Psychopathology and Therapy; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Solcoff, K.D.V. (Ed.) Memoria autobiográfica y espectro autista. In Autismo: Enfoques Actuales. Una guía para Padres y Profesionales de la Salud y la Educación; Intellectus Partners: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2001; pp. 151–194. [Google Scholar]

- Solcoff, K. ¿Fenomenología experimental de la memoria? La memoria autobiográfica entre el contexto y el significado [Autobiographical memory and autism spectrum]. Estud. Psicol. 2001, 22, 319–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solcoff, K. La edad de la memoria. El recuerdo biográfico y la representación de estados mentales autorreferenciales [Experimental phenomenology of memory? Autobiographical memory between context and meaning]. Propues. Educ. 2002, 25, 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Schoen, S.A.; Miller, L.J.; Brett-Green, B.A.; Nielsen, D.M. Physiological and behavioral differences in sensory processing: A comparison of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Sensory Modulation Disorder. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2009, 3, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Sasson, A.; Hen, L.; Fluss, R.; Cermak, S.A.; Engel-Yeger, B.; Gal, E. A meta-analysis of sensory modulation symptoms in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2009, 39, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delacato, C.H. The Ultimate Stranger: The Autistic Child; Doubleday & Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1974; ISBN 0385010745. [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan, S. An analysis of score patterns of children with attention disorders on the sensory integration and praxis tests. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 1996, 50, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, W. The impact of sensory processing abilities on the daily lives of young children and their families: A conceptual model. Infants Young Child. 1997, 9, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, W. Sensory Profile; Texas Psicol. Corp.: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, L.J.; Reisman, J.; McIntosh, D.N.; Simon, J. An ecological model of sensory modulation: Performance of children with fragile X syndrome, autism, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and sensory modulation dysfunction. In Understanding the Nature of Sensory Integration with Diverse Populations; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 57–88. [Google Scholar]

- Iandolo, G.; Esposito, G.; Venuti, P. Cohesión, micro-organización, estructura narrativa y competencias verbales entre tres y once años: El desarrollo narrativo formal. Estud. Psicol. 2013, 34, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, C.; Risi, S.; Lambrecht, L.; Cook, E.H.; Leventhal, B.L.; Dilavore, P.C.; Pickles, A.; Rutter, M. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Generic: A standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2000, 30, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, C.; Rutter, M.; DiLavore, P.; Risi, S.; Gotham, K.; Bishop, S. Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, 2nd ed.; Western Psychological Services (WPS): Torrance, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Hidalgo, P.; Roigé-Castellví, J.; Hernández-Martínez, C.; Voltas, N.; Canals, J. Prevalence and Characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Spanish School-Age Children. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2018, 48, 3176–3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banach, R.; Thompson, A.; Szatmari, P.; Goldberg, J.; Tuff, L.; Zwaigenbaum, L.; Mahoney, W. Brief report: Relationship between non-verbal IQ and gender in autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2009, 39, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werling, D.M.; Geschwind, D.H. Sex differences in autism spectrum disorders. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2013, 26, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, C.D. Differential Abilities Scale (DAS); TX Psychol. Corp.: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, A.; Pickering, K.; Lord, C.; Pickles, A. Mixed and multi-level models for longitudinal data: Growth curve models of language development. In Statistical Analysis of Medical Data: New Developments; Hodder Education Publishers: London, UK, 1998; pp. 127–142. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, D.K.; Lord, C.; Risi, S.; DiLavore, P.S.; Shulman, C.; Thurm, A.; Welch, K.; Pickles, A. Patterns of Growth in Verbal Abilities Among Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 75, 594–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, C.; Kamphaus, R. Reynolds Intellectual Assessment Scale (RIAS). Lutz, FL Psychol. Assess. Resour. 2003, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Sánchez, F.; Fernández-Pinto, I.; Santamaría, P.; Carrasco, M.Á.; Del Barrio, V. SENA, Sistema de Evaluación de Niños y Adolescentes [ENA, Child and Adolescent Assessment System]. Rev. Psicol. Clínica Niños Adolesc. 2016, 3, 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein, M.H.; Tamis-LeMonda, C.S. The Bear Family. Cognitive Coding Handbook; Unpublished Manual; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development: Bethesda, MD, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, G.; Venuti, P.; Iandolo, G.; de Falco, S.; Gabrieli, G.; Wei, C.; Bornstein, M.H. Microgenesis of typical storytelling. Early Child Dev. Care 2020, 190, 1991–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iandolo, G.; Esposito, G.; Venuti, P. The bears family projective test: Evaluating stories of children with emotional difficulties. Percept. Mot. Skills 2012, 114, 883–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iandolo, G. El Desarrollo de las Competencias Narrativas: Forma, Cohesión y Equilibrio de Contenido a Través del Test Proyectivo de la Familia de los Osos [The development of narrative competences: Form, cohesion and balance of content through the Projective Test of the Bear Family]. PhD. Thesis, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Venuti, P. L’osservazione del Comportamento: Ricerca Psicologica e Pratica Clinica [Observation of behavior: Psychological research and clinical practice]; Carocci: Roma, Italy, 2001; ISBN 8843018175. [Google Scholar]

- Bentenuto, A. Studio della Relazione Genitore—Bambino in Soggetti con Disturbo dello Spettro Autistico [Observation of behavior: Psychological research and clinical practice]. PhD Thesis, University of Trento, Trento, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bizzego, A.; Battisti, A.; Gabrieli, G.; Esposito, G.; Furlanello, C. Pyphysio: A physiological signal processing library for data science approaches in physiology. SoftwareX 2019, 10, 100287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iandolo, G.; López-Florit, L.; Venuti, P.; Neoh, M.J.Y.; Bornstein, M.H.; Esposito, G. Story contents and intensity of the anxious symptomatology in children and adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2020, 25, 725–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A Coefficient of Agreement for Nominal Scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, 20, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, U.R.; Joseph, K.P.; Kannathal, N.; Lim, C.M.; Suri, J.S. Heart rate variability: A review. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2006, 44, 1031–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoshi, R.A.; Pastre, C.M.; Vanderlei, L.C.M.; Godoy, M.F. Poincaré plot indexes of heart rate variability: Relationships with other nonlinear variables. Auton. Neurosci. Basic Clin. 2013, 177, 271–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taelman, J.; Vandeput, S.; Spaepen, A.; Van Huffel, S. Influence of mental stress on heart rate and heart rate variability. In Proceedings of the IFMBE, Antwerp, Belgium, 23–27 November 2008; Volume 22, pp. 1366–1369. [Google Scholar]

- Dishman, R.K.; Nakamura, Y.; Garcia, M.E.; Thompson, R.W.; Dunn, A.L.; Blair, S.N. Heart rate variability, trait anxiety, and perceived stress among physically fit men and women. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2000, 37, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales-Soto, G.; Corsini-Pino, R.; Monsálves-Álvarez, M.; Yáñez-Sepúlveda, R. Respuesta del balance simpático-parasimpático de la variabilidad de la frecuencia cardíaca durante una semana de entrenamiento aeróbico en ciclistas de ruta [Response of the sympathetic-parasympathetic balance of heart rate variability during a week of aerobic training in road cyclists]. Rev. Andal. Med. Deport. 2016, 9, 143–147. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez Sotelo, O. Variabilidad de la frecuencia cardíaca en individuos sanos costarricenses [Heart rate variability in healthy Costa Rican individuals]. Rev. Costarric. Cardiol 2000, 2, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Ruiz, S.; Ruiz-Padial, E.; Vera, N.; Fernández, C.; Anllo-Vento, L.; Vila, J. Effect of heart rate variability on defensive reaction and eating disorder symptomatology in chocolate cravers. J. Psychophysiol. 2009, 23, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechara, A.; Damasio, A.R. The somatic marker hypothesis: A neural theory of economic decision. Games Econ. Behav. 2005, 52, 336–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, E.S.; Graham, S.A. The relations between children’s communicative perspective-taking and executive functioning. Cogn. Psychol. 2009, 58, 220–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula-Pérez, I. Coocurrencia entre ansiedad y autismo. las hipótesis del error social y de la carga alostática [Co-occurrence between anxiety and autism. the social error and allostatic load hypotheses]. Rev. Neurol. 2013, 56 (Suppl. 1), 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Paula, I. La Ansiedad en el Autismo [Anxiety in autism]; Alianza Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2015; p. 296. [Google Scholar]

- Zelazo, P.D.; Müller, U.; Frye, D.; Marcovitch, S.; Argitis, G.; Boseovski, J.; Chiang, J.K.; Hongwanishkul, D.; Schuster, B.V.; Sutherland, A. The development of executive function in early childhood. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 2003, 68, 7–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Céspedes, J.M.; Tirapu-Ustárroz, J. Rehabilitación de las funciones ejecutivas [Rehabilitation of executive functions]. Rev. Neurol. 2004, 38, 656–663. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bernard-Opitz, V. Pragmatic analysis of the communicative behavior of an autistic child. J. Speech Hear. Disord. 1982, 47, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, F.D.M. Aspectos funcionais da comunicaçäo de crianças autistas [Functional aspects of the communication of autistic children]. Temas Desenvolv 2000, 9, 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Garay, A.; Iñiguez, L.; Martínez, L.M. La perspectiva discursiva en psicología social [The discursive perspective in social psychology]. Subj. Procesos Cogn. 2005, 7, 105–130. [Google Scholar]

- Nigg, J.T.; Hinshaw, S.P.; Huang-Pollock, C. Disorders of Attention and Impulse Regulation. In Developmental Psychopathology, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; Volume 3, pp. 358–403. ISBN 9780470939406. [Google Scholar]

- Miilher, L.P.; Fernandes, F.D.M. Analyses of the communicative functions expressed by language therapists and patients of the autistic spectrum. Pro. Fono. 2006, 18, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, E.L.; Fredrickson, B.; Kring, A.M.; Johnson, D.P.; Meyer, P.S.; Penn, D.L. Upward spirals of positive emotions counter downward spirals of negativity: Insights from the broaden-and-build theory and affective neuroscience on the treatment of emotion dysfunctions and deficits in psychopathology. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 849–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaherche, E.; Chetouani, M.; Mahdhaoui, A.; Saint-Georges, C.; Viaux, S.; Cohen, D. Interpersonal synchrony: A survey of evaluation methods across disciplines. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2012, 3, 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelantado, N. Diferencias Individuales en el Fraccionamiento Direccional de las Respuestas Electrodérmicas y Cardíacas Ante Estímulos con Diferente Carga Emocional [Individual Differences in Directional Fractionation of Electrodermal and Cardiac Responses to Stimuli with Different Emotional Charges]. PhD. Thesis, Universidad de Murcia, Murcia, Spain, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- López-de-la-Nieta, O.; Koeneke Hoenicka, M.A.; Martinez-Rubio, J.L.; Shinohara, K.; Esposito, G.; Iandolo, G. Exploration of the Spanish Version of the Attachment Style Questionnaire: A Comparative Study between Spanish, Italian, and Japanese Culture. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2021, 11, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koegel, R.L.; O’Dell, M.C.; Koegel, L.K. A natural language teaching paradigm for nonverbal autistic children. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 1987, 17, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koegel, L.K. Interventions to facilitate communication in autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2000, 30, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biringen, Z.; Damon, J.; Grigg, W.; Mone, J.; Pipp-Siegel, S.; Skillern, S.; Stratton, J. Emotional availability: Differential predictions to infant attachment and kindergarten adjustment based on observation time and context. Infant Ment. Health J. 2005, 26, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siller, M.; Sigman, M. The Behaviors of Parents of Children with Autism Predict the Subsequent Development of Their Children’s Communication. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2002, 32, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Min | Max | Average | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronological age—years | 6 | 18 | 12.0 | 3.00 | −0.12 | −0.13 |

| Equivalent age (IQ-RIAS)—years | 4.6 | 18 | 12.50 | 3.29 | −0.45 | 0.08 |

| General IQ (IG-RIAS) ① | 62 | 120 | 96.38 | 16.01 | −0.25 | −0.64 |

| Verbal IQ (IV-RIAS) ① | 59 | 125 | 94.92 | 21.50 | −0.34 | −1.01 |

| Non-verbal IQ (INV-RIAS) ① | 66 | 120 | 97.81 | 15.06 | −0.40 | −0.86 |

| Verbal memory IQ (IM-RIAS) ① | 60 | 120 | 97.23 | 14.48 | −0.49 | 0.82 |

| ADOS/ ADOS-2 module ② | 2 | 4 | ||||

| Total ADOS/ ADOS-2 score ② | 7 | 12 | 10 | 1.37 | 0.43 | −0.36 |

| Number of propositions (Bears Family story) | 0 | 75 | 23.08 | 23.58 | 1.37 | 0.42 |

| Number of episodes (Bears Family story) | 0 | 40 | 11.00 | 10.53 | 1.86 | 3.36 |

| Cohesion index (Bears Family story) ③ | 0 | 10 | 5.00 | 2.87 | −0.10 | −1.11 |

| Structure index (Bears Family story) ④ | 0 | 6 | 3.17 | 2.12 | 0.12 | −1.56 |

| Global problem index (SENA-self report) ⑤ | 39 | 81 | 55.48 | 10.80 | 0.39 | 0.09 |

| Emotional problems (SENA-self report) ⑤ | 40 | 76 | 55.35 | 12.09 | 0.33 | −1.55 |

| Behavioral problems (SENA-self report) ⑤ | 41 | 88 | 55.35 | 15.03 | 1.02 | −0.03 |

| Executive functions problems (SENA-self report) ⑤ | 39 | 79 | 53.70 | 10.99 | 0.45 | −0.15 |

| Personal resources (SENA-self report) ⑤ | 15 | 54 | 38.65 | 9.75 | −0.58 | 0.58 |

| Self-esteem (SENA-self report) ⑤ | 21 | 62 | 44.70 | 9.67 | −0.29 | 0.40 |

| Global problem index (SENA-family report) ⑤ | 44 | 82 | 63.12 | 11.73 | 0.33 | −1.16 |

| Emotional problems (SENA-family report) ⑤ | 36 | 84 | 61.88 | 15.85 | −0.33 | −1.11 |

| Behavioral problems (SENA-family report) ⑤ | 40 | 90 | 57.80 | 13.97 | 0.85 | 0.26 |

| Executive functions problems (SENA-family report) ⑤ | 53 | 83 | 65.16 | 10.37 | 0.58 | −1.12 |

| Personal resources (SENA-family report) ⑤ | 21 | 50 | 34.64 | 8.32 | 0.02 | −0.44 |

| Global problem index (SENA-teacher report) ⑤ | 44 | 83 | 56.56 | 12.45 | 1.32 | 0.87 |

| Emotional problems (SENA-teacher report) ⑤ | 46 | 64 | 53.63 | 6.37 | 0.27 | −1.44 |

| Behavioral problems (SENA-teacher report) ⑤ | 44 | 88 | 54.69 | 14.30 | 1.75 | 2.36 |

| Executive functions (SENA-teacher report) ⑤ | 50 | 84 | 59.31 | 12.43 | 1.25 | 0.14 |

| Personal resources (SENA-teacher report) ⑤ | 13 | 46 | 32.50 | 10.48 | −0.11 | −1.21 |

| Group | SD2 Mean/SD |

|---|---|

| Group 1 (Low Sympathetic Activity –Low Stress Level) | 334,754/58,964 |

| Group 2 (High Sympathetic Activity –High Stress Level) | 92,518/38,868 |

| Online Therapy Session | Min | Max | Average | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Session duration (seconds) | 773 | 3000 | 1851.92 | 667.01 | 0.01 | −1.17 |

| Number of turn-taking events (frequency) | 38 | 202 | 117.69 | 51.06 | −0.15 | −1.22 |

| Ratio—session duration (seconds)/total number of turn-taking events (frequency) | 11 | 29 | 16.96 | 4.75 | 0.94 | 0.30 |

| Patient’s Characteristics | Child Accepts (NA) | Child Expands (NAm) | Patient Does Not Share (NNcC) | Patient Does Not Accept (NNA) | Patient Does Not Share and Proposes (NNcP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronological age | r = −0.50 p = 0.05 | r = 0.40 p = 0.05 | |||

| Number of propositions (Bears Family story) | r = 0.46 p = 0.05 | ||||

| Cohesion index (Bears Family story) | r = −0.51 p = 0.01 | ||||

| Self-esteem (SENA-self report) | r = −0.57 p = 0.01 | ||||

| Personal resources (SENA-parental report) | r = −0.47 p = 0.05 |

| Therapist’s Behavior | Group | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Therapist ends (TT) - behavioral frequency - | Group 1 (Low Sympathetic Activity—Low Stress) | 1.2 | 0.63 |

| Group 2 (High Sympathetic Activity—High Stress) | 0.56 | 0.51 |

| Behavior | Mean | Median | Variance | Std. Dev. | Min. | Max. | Range | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co-oriented therapist | 327.32 | 318.31 | 23,587.96 | 153.58 | 21.34 | 813.49 | 792.16 | 0.42 | −0.05 |

| Therapist expands (TA) | 332.71 | 332.81 | 20,231.79 | 142.24 | 21.34 | 891.48 | 870.15 | 0.06 | −0.05 |

| Therapist directs attention (TDAt) | 411.73 | 462.02 | 18,996.30 | 137.83 | 135.46 | 625.71 | 490.24 | −0.56 | −0.99 |

| Therapist directs action (TDAc) | 429.52 | 451.02 | 18,178.90 | 134.83 | 37.02 | 719.27 | 682.25 | −1.34 | 2.11 |

| Therapist interrupts (TI) | 458.45 | 518.71 | 15,643.51 | 125.07 | 248.08 | 630.02 | 381.94 | −0.92 | −0.59 |

| Therapist proposes (T*) | 537.27 | 580.35 | 15,435.04 | 124.24 | 367.92 | 686.61 | 318.69 | −0.51 | −1.57 |

| Behavior | Mean | Median | Variance | Std. Dev. | Min. | Max. | Range | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient expands (NAm) | 329.97 | 321.05 | 23,810.13 | 154.31 | 21.34 | 813.49 | 792.16 | 0.39 | −0.12 |

| Patient shares (NC) | 334.62 | 335.04 | 20,277.21 | 142.40 | 21.34 | 891.48 | 870.15 | 0.07 | −0.01 |

| Patient does not share (NNcC) | 368.53 | 407.46 | 25,309.95 | 159.09 | 42.17 | 719.27 | 677.10 | −0.48 | −0.88 |

| Patient does not share and proposes (NNcP) | 383.77 | 394.58 | 13,807.32 | 117.50 | 198.01 | 557.53 | 359.53 | −0.29 | −1.22 |

| Patient accepts (NA) | 461.70 | 440.47 | 6395.40 | 79.97 | 367.92 | 605.74 | 237.82 | 0.61 | −0.98 |

| Patient does not accept (NNA) | 618.49 | 614.61 | 1983.16 | 44.53 | 563.59 | 686.61 | 123.02 | 0.20 | −1.39 |

| Kolmogorov-Smirnov | Shapiro-Wilk | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | df | Sig. | Statistic | df | Sig. | |||

| Therapist | SD2 | M* | 0.251 | 15 | 0.012 | 0.823 | 15 | 0.007 |

| MA | 0.023 | 1808 | 0.025 | 0.994 | 1808 | 0.000 | ||

| MC | 0.047 | 1300 | 0.000 | 0.983 | 1300 | 0.000 | ||

| MDAc | 0.189 | 86 | 0.000 | 0.868 | 86 | 0.000 | ||

| MDAt | 0.176 | 113 | 0.000 | 0.904 | 113 | 0.000 | ||

| MI | 0.229 | 22 | 0.004 | 0.807 | 22 | 0.001 | ||

| Patient | SD2 | NA | 0.185 | 22 | 0.048 | 0.886 | 22 | 0.016 |

| NAm | 0.045 | 1318 | 0.000 | 0.984 | 1318 | 0.000 | ||

| NC | 0.023 | 1729 | 0.039 | 0.994 | 1729 | 0.000 | ||

| NNA | 0.133 | 10 | 0.200 | 0.935 | 10 | 0.501 | ||

| NNcC | 0.126 | 185 | 0.000 | 0.936 | 185 | 0.000 | ||

| NNcP | 0.116 | 80 | 0.009 | 0.913 | 80 | 0.000 | ||

| Therapist SD2 (HRV) Grouped by Therapist’s Turn-Taking Interactive Behavior. (TMC, TA, TDAt, TDAc, TI, T*) | Therapist SD2 (HRV) Grouped by Patient’s Turn-Taking Interactive Behavior. (NAm, NC, NNcC, NNcP, NA, NNA) | |

|---|---|---|

| Chi-Square Statistical | 124.710 | 75.292 |

| Asymp. Sig. | 0.001 | 0.001 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

López-Florit, L.; García-Cuesta, E.; Gracia-Expósito, L.; García-García, G.; Iandolo, G. Physiological Reactions in the Therapist and Turn-Taking during Online Psychotherapy with Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 586. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11050586

López-Florit L, García-Cuesta E, Gracia-Expósito L, García-García G, Iandolo G. Physiological Reactions in the Therapist and Turn-Taking during Online Psychotherapy with Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Brain Sciences. 2021; 11(5):586. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11050586

Chicago/Turabian StyleLópez-Florit, Laura, Esteban García-Cuesta, Luis Gracia-Expósito, German García-García, and Giuseppe Iandolo. 2021. "Physiological Reactions in the Therapist and Turn-Taking during Online Psychotherapy with Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder" Brain Sciences 11, no. 5: 586. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11050586

APA StyleLópez-Florit, L., García-Cuesta, E., Gracia-Expósito, L., García-García, G., & Iandolo, G. (2021). Physiological Reactions in the Therapist and Turn-Taking during Online Psychotherapy with Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Brain Sciences, 11(5), 586. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11050586