COVID-19, Isolation, Quarantine: On the Efficacy of Internet-Based Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) and Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for Ongoing Trauma

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure and Treatments

2.3. Measures and Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cahill, S.P.; Carrigan, M.H.; Frueh, B.C. Does EMDR work? And if so, why?: A critical review of controlled outcome and dismantling research. J. Anxiety Disord. 1999, 13, 5–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiente-Gómez, A.; Moreno-Alcázar, A.; Treen, D.; Cedrón, C.; Colom, F.; Pérez, V.; Amann, B.L. EMDR beyond PTSD: A Systematic Literature Review. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yunitri, N.; Kao, C.-C.; Chu, H.; Voss, J.; Chiu, H.-L.; Liu, D.; Shen, S.-T.H.; Chang, P.-C.; Kang, X.L.; Chou, K.-R. The effectiveness of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing toward anxiety disorder: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 123, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korn, D.L. EMDR and the treatment of complex PTSD: A review. J. EMDR Pract. Res. 2009, 3, 264–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foa, E.B.; Keane, T.M.; Friedman, M.J.; Cohen, J.A. Effective Treatments for PTSD: Guidelines from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Etten, M.V.; Taylor, S. Comparative Efficacy of Treatments for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Meta-Analysis. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 1998, 5, 126–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devilly, G.J.; Spence, S.H. The relative efficacy and treatment distress of EMDR and a cognitive-behavior trauma treatment protocol in the amelioration of posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Anxiety Disord. 1999, 13, 131–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Thordarson, D.S.; Maxfield, L.; Fedoroff, I.C.; Lovell, K.; Ogrodniczuk, J. Comparative efficacy, speed, and adverse effects of three PTSD treatments: Exposure therapy, EMDR, and relaxation training. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2003, 71, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ironson, G.; Freund, B.; Strauss, J.L.; Williams, J. Comparison of two treatments for traumatic stress: A community-based study of EMDR and prolonged exposure. J. Clin. Psychol. 2002, 58, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.; Gavriel, H.; Drummond, P.; Richards, J.; Greenwald, R. Treatment of PTSD: Stress inoculation training with prolonged exposure compared to EMDR. J. Clin. Psychol. 2002, 58, 1071–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, K.; McGoldrick, T.; Brown, K.; Buchanan, R.; Sharp, D.; Swanson, V.; Karatzias, A. A controlled comparison of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing versus exposure plus cognitive restructuring versus waiting list in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2002, 9, 299–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, K.; Armstrong, M.S.; Gold, R.; O’Connor, N.; Jenneke, W.; Tarrier, N. A trial of eye movement desensitization compared to image habituation training and applied muscle relaxation in post-traumatic stress disorder. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 1994, 25, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, N.P.; Kitchiner, N.J.; Kenardy, J.; Lewis, C.E.; Bisson, J.I. Early psychological intervention following recent trauma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2019, 10, 1695486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, C.; Roberts, N.P.; Andrew, M.; Starling, E.; Bisson, J.I. Psychological therapies for post-traumatic stress disorder in adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2020, 11, 1729633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidler, G.H.; Wagner, F.E. Comparing the efficacy of EMDR and trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of PTSD: A meta-analytic study. Psychol. Med. 2006, 36, 1515–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatzias, T.; Murphy, P.; Cloitre, M.; Bisson, J.; Roberts, N.; Shevlin, M.; Hyland, P.; Maercker, A.; Ben-Ezra, M.; Coventry, P. Psychological interventions for ICD-11 complex PTSD symptoms: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 2019, 49, 1761–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, E. EMDR treatment of recent trauma. J. EMDR Pract. Res. 2009, 3, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, E.; Laub, B. Early EMDR Intervention (EEI): A Summary, a Theoretical Model, and the Recent Traumatic Episode Protocol (R-TEP). J. EMDR Pract. Res. 2008, 2, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, L.K.; Cohen, J.A.; Mannarino, A.P. Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for youth who experience continuous traumatic exposure. Peace Confl. J. Peace Psychol. 2013, 19, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.A.; Mannarino, A.P.; Murray, L.K. Trauma-focused CBT for youth who experience ongoing traumas. Child Abus. Negl. 2011, 35, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.A.; Mannarino, A.P.; Kliethermes, M.; Murray, L.A. Trauma-focused CBT for youth with complex trauma. Child Abus. Negl. 2012, 36, 528–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaghrout-Hodali, M.; Alissa, F.; Dodgson, P.W. Building resilience and dismantling fear: EMDR group protocol with children in an area of ongoing trauma. J. EMDR Pract. Res. 2008, 2, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acarturk, C.; Konuk, E.; Cetinkaya, M.; Senay, I.; Sijbrandij, M.; Gulen, B.; Cuijpers, P. The efficacy of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing for post-traumatic stress disorder and depression among Syrian refugees: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Psychol. Med. 2016, 46, 2583–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehnung, M.; Shapiro, E.; Schreiber, M.; Hofmann, A. Evaluating the EMDR Group traumatic episode protocol with refugees: A field study. J. EMDR Pract. Res. 2017, 11, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK). Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: The Management of PTSD in Adults and Children in Primary and Secondary Care; National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: Guidance; Gaskell: Leicester, UK, 2005; ISBN 978-1-904671-25-1. [Google Scholar]

- Barak, A.; Hen, L.; Boniel-Nissim, M.; Shapira, N. A comprehensive review and a meta-analysis of the effectiveness of internet-based psychotherapeutic interventions. J. Technol. Hum. Serv. 2008, 26, 109–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blevins, C.A.; Weathers, F.W.; Davis, M.T.; Witte, T.K.; Domino, J.L. The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and Initial Psychometric Evaluation. J. Trauma. Stress 2015, 28, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielberger, C.D. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory STAI (Form Y) (“Self-Evaluation Questionnaire”); Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Brown, G.K. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II; Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, R.A.; Creamer, M.; O’Donnell, M.; Silove, D.; McFarlane, A.C. The capacity of acute stress disorder to predict posttraumatic psychiatric disorders. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2012, 46, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagani, M.; Carletto, S. A hypothetical mechanism of action of EMDR: The role of slow wave sleep. Clin. Neuropsychiatry J. Treat. Eval. 2017, 14, 301–305. [Google Scholar]

- Landin-Romero, R.; Moreno-Alcazar, A.; Pagani, M.; Amann, B.L. How Does Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing Therapy Work? A Systematic Review on Suggested Mechanisms of Action. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, P.R.; Parker, K.C. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR): A meta-analysis. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2001, 69, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffries, F.W.; Davis, P. What is the role of eye movements in eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)? A review. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2013, 41, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek, J.; Lee, S.; Cho, T.; Kim, S.-W.; Kim, M.; Yoon, Y.; Kim, K.K.; Byun, J.; Kim, S.J.; Jeong, J. Neural circuits underlying a psychotherapeutic regimen for fear disorders. Nature 2019, 566, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, A. Biological Clues to an Enigmatic Treatment for Traumatic Stress. Nature 2019, 566, 335–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hembree, E.A.; Rauch, S.A.; Foa, E.B. Beyond the manual: The insider’s guide to prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2003, 10, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Session | EMDR | TF-CBT |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | General anamnesis; presentation of the intervention; instructions and invitation to fill in the online assessment | General anamnesis; presentation of the intervention; instructions and invitation to fill in the online assessment |

| 2 | Trauma psychoeducation; sleep quality and eating monitoring; “four elements” and “safe place” exercise; homework: to practice the exercise 2–3 times a day | Trauma psychoeducation; sleep quality and eating monitoring; “four elements” and “safe place” exercise; breathing retraining and grounding; homework: to practice the exercise 2–3 times a day |

| 3 | Stabilization exercises. Training on the relational and mastery skills | Stabilization exercises. Jacobson’s Progressive muscle relaxation; homework: practice relaxation, grounding and breathing retraining every day |

| 4 | Recent events protocol; Exposure with self-tapping. Identifying and desensitizing first Points of Disturbance (PoD) with Bilateral Stimulation (Tapping or Butterfly Hug) | Traumatic events/situations: prolonged verbal exposure and cognitive restructuring; identifying the most disturbing avoidance behaviour to deal with in vivo exposure; brief mindfulness training; homework: listening the recorded session, practice the relaxation, breathing retraining or safe place exercise after each exposure |

| 5 | PoDs identification and desensitization with Bilateral Stimulation (part 1) | |

| 6 | PoDs identification and desensitization with Bilateral Stimulation (part 2) | |

| 7 | Review and closure | Review and closure |

| EMDR | TF-CBT | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Follow-Up | Pre | Post | Follow-Up | |

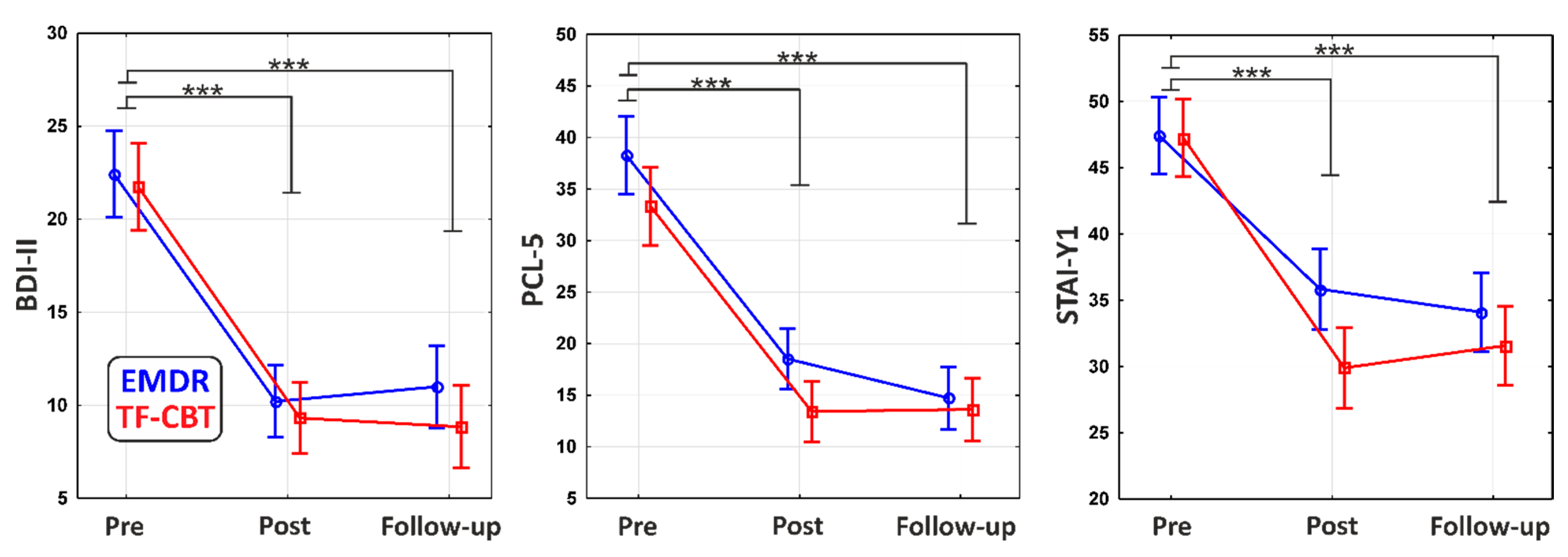

| BDI-II | 22.4 (10.5) | 10.2 (6.4) | 11 (9.3) | 21.7 (9.6) | 9.3 (9.9) | 8.8 (10.1) |

| PCL-5 | 38.2 (16.7) | 18.5 (12.3) | 14.7 (13.7) | 33.3 (16.2) | 13.4 (12.9) | 13.6 (12.5) |

| STAY-Y1 | 47.4 (13.1) | 35.8 (14.5) | 34.1 (14.9) | 47.2 (12.2) | 29.8 (11.8) | 31.5 (10.6) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Perri, R.L.; Castelli, P.; La Rosa, C.; Zucchi, T.; Onofri, A. COVID-19, Isolation, Quarantine: On the Efficacy of Internet-Based Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) and Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for Ongoing Trauma. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 579. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11050579

Perri RL, Castelli P, La Rosa C, Zucchi T, Onofri A. COVID-19, Isolation, Quarantine: On the Efficacy of Internet-Based Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) and Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for Ongoing Trauma. Brain Sciences. 2021; 11(5):579. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11050579

Chicago/Turabian StylePerri, Rinaldo Livio, Paola Castelli, Cecilia La Rosa, Teresa Zucchi, and Antonio Onofri. 2021. "COVID-19, Isolation, Quarantine: On the Efficacy of Internet-Based Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) and Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for Ongoing Trauma" Brain Sciences 11, no. 5: 579. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11050579

APA StylePerri, R. L., Castelli, P., La Rosa, C., Zucchi, T., & Onofri, A. (2021). COVID-19, Isolation, Quarantine: On the Efficacy of Internet-Based Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) and Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for Ongoing Trauma. Brain Sciences, 11(5), 579. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11050579