Symbiosis in Health: The Powerful Alliance of AI and Propensity Score Matching in Real World Medical Data Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What are the dynamic and spatial features of the research literature production of the AI and PSM use in medicine?

- How is the symbiosis association between AI and PSM reflected in most prolific source titles and most productive countries?

- What research themes emerge in studies combining AI and PSM for medical data analysis?

- What are the more prolific AI methods, medical applications, and diagnoses in combined AI and PSM analyses?

- What are the dominant research trends in the combined use of PSM and AI?

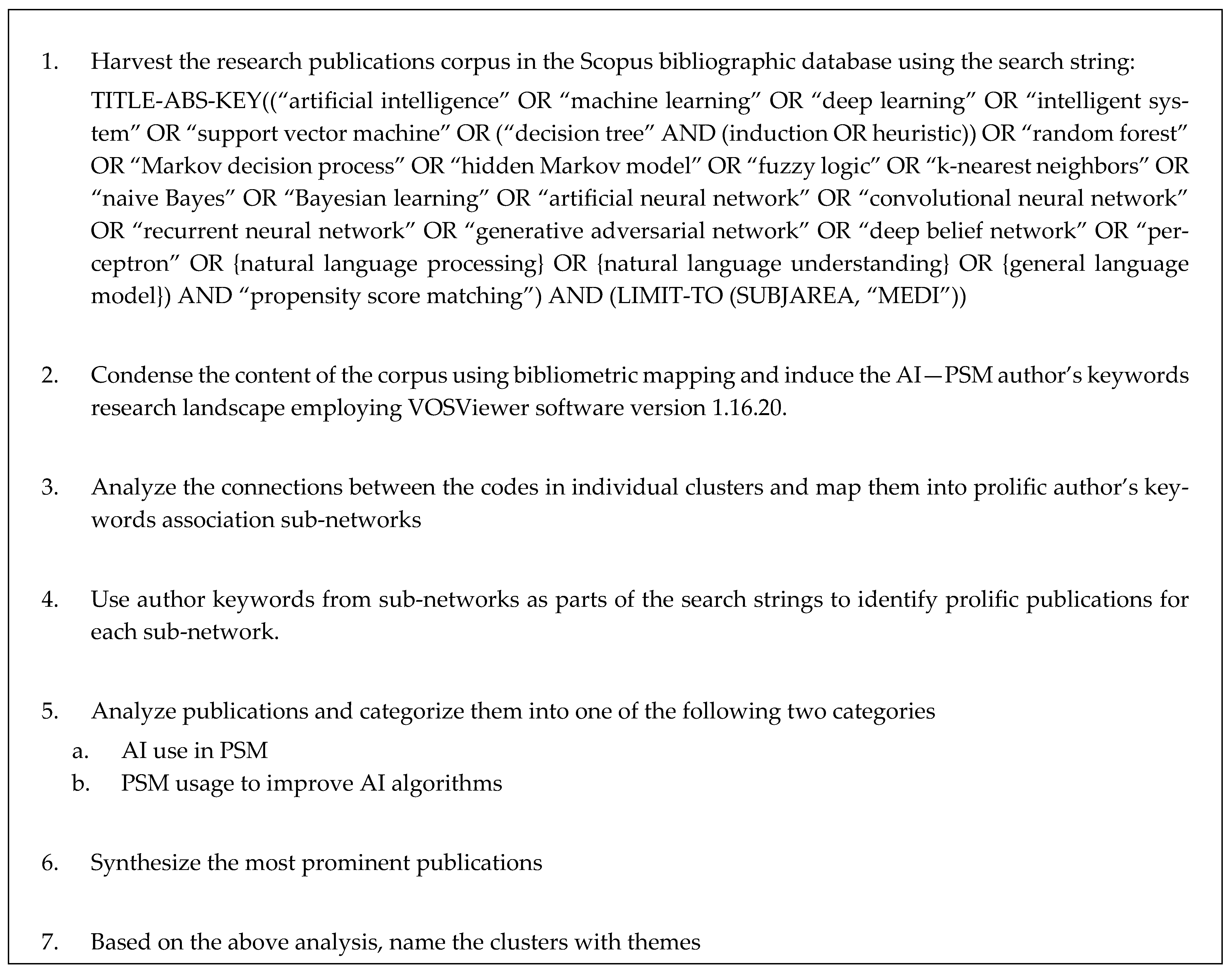

2. Methodology

3. Results

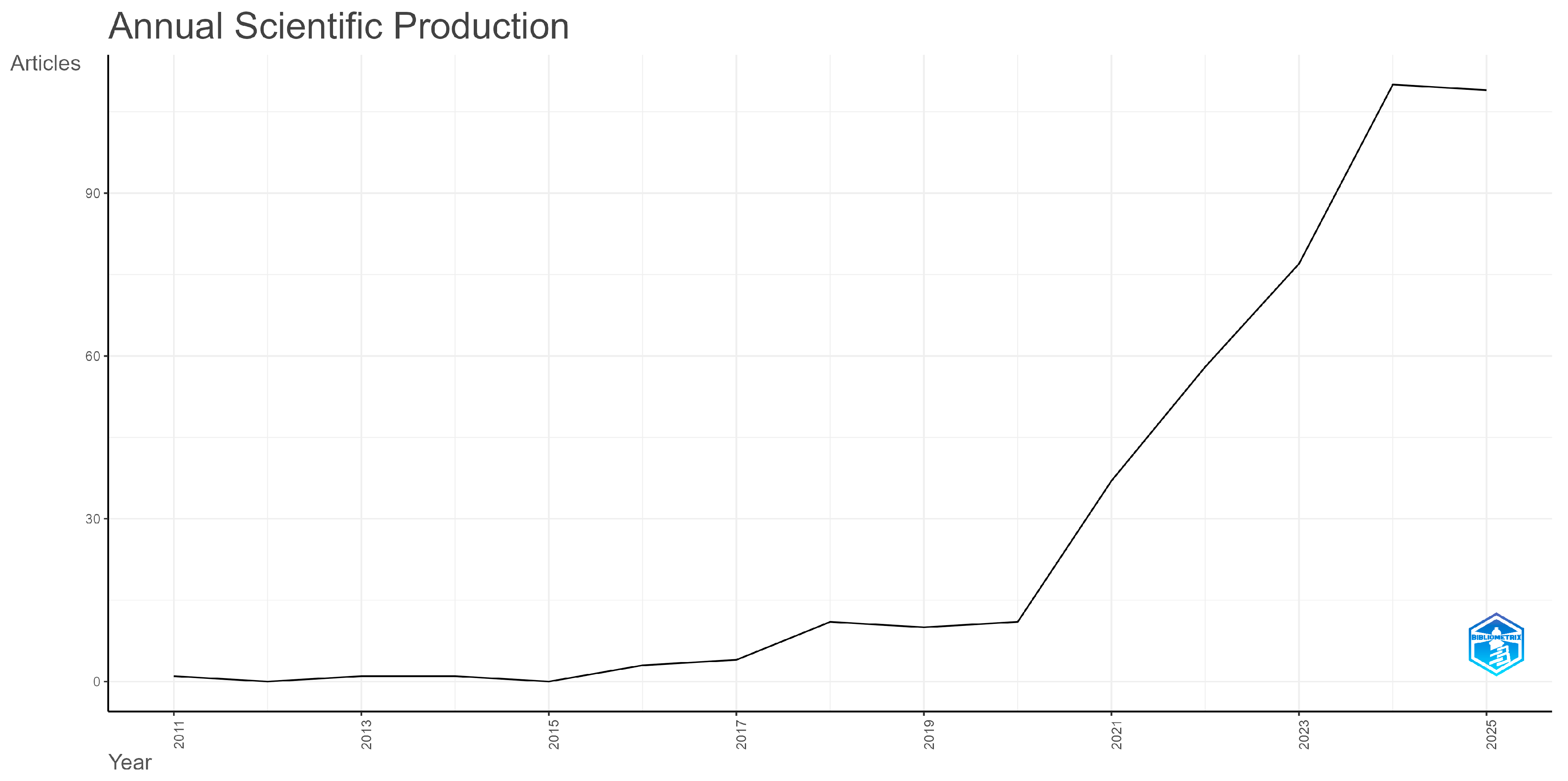

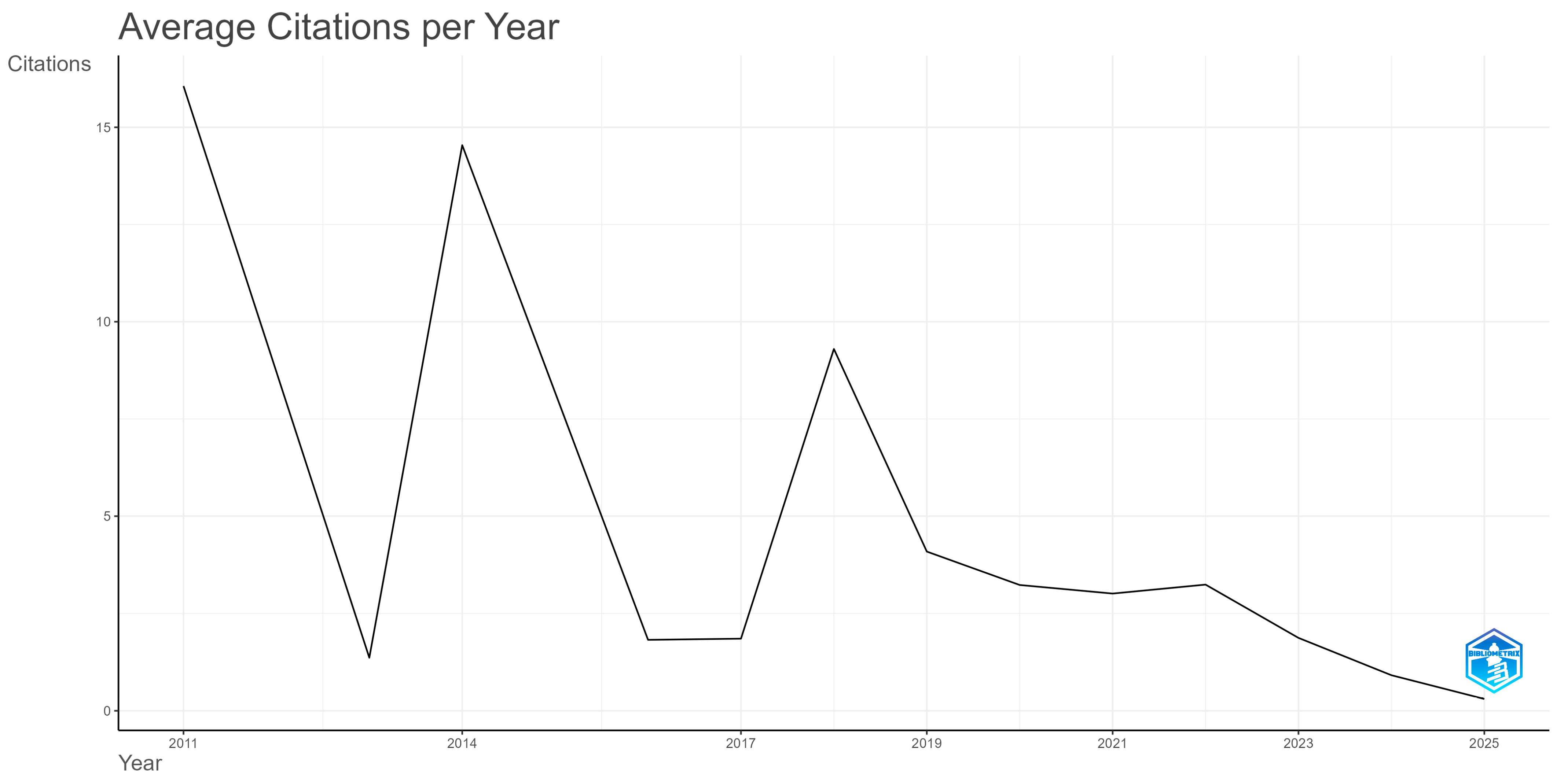

3.1. Dynamic and Spatial Features of the Research Literature Production

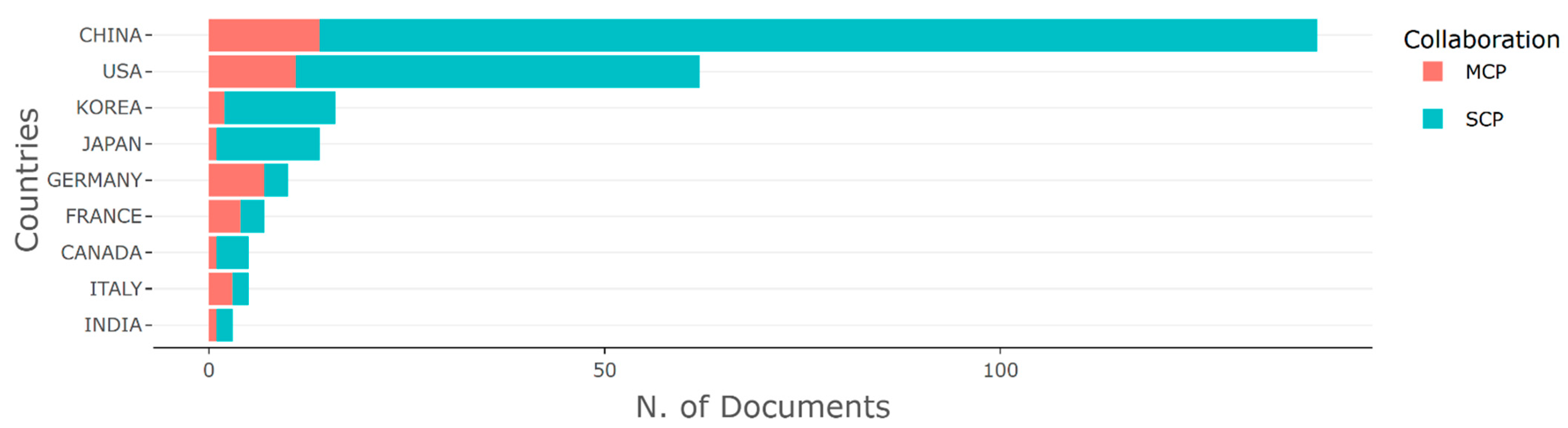

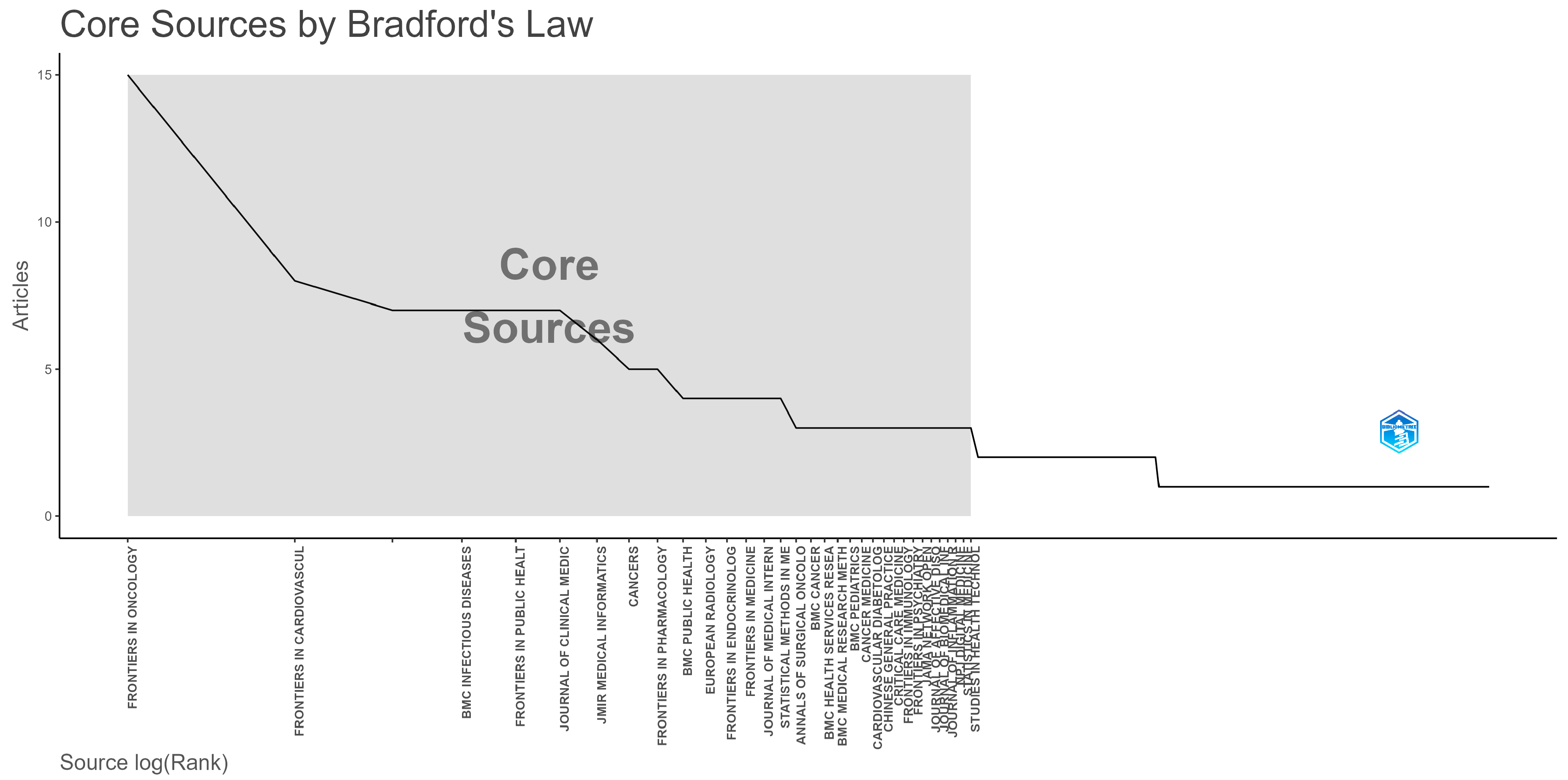

3.2. Productive Countries and Source Titles

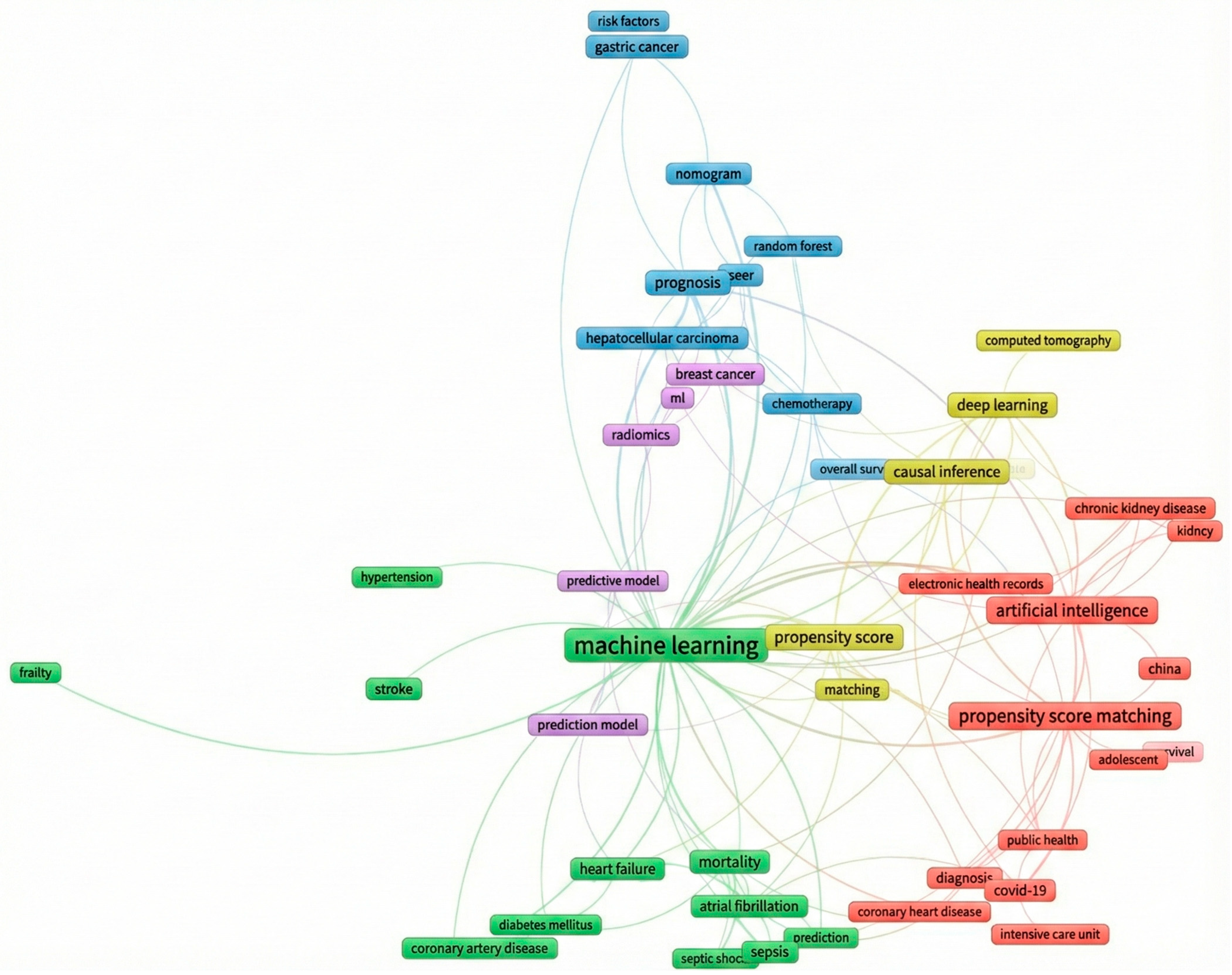

3.3. More Prolific Themes

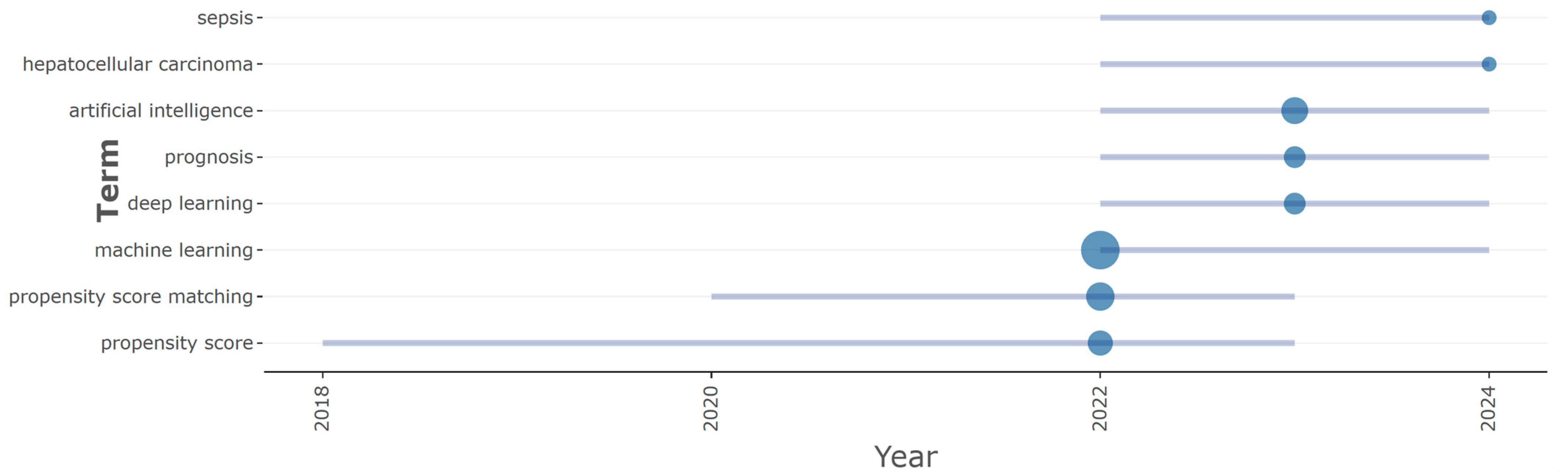

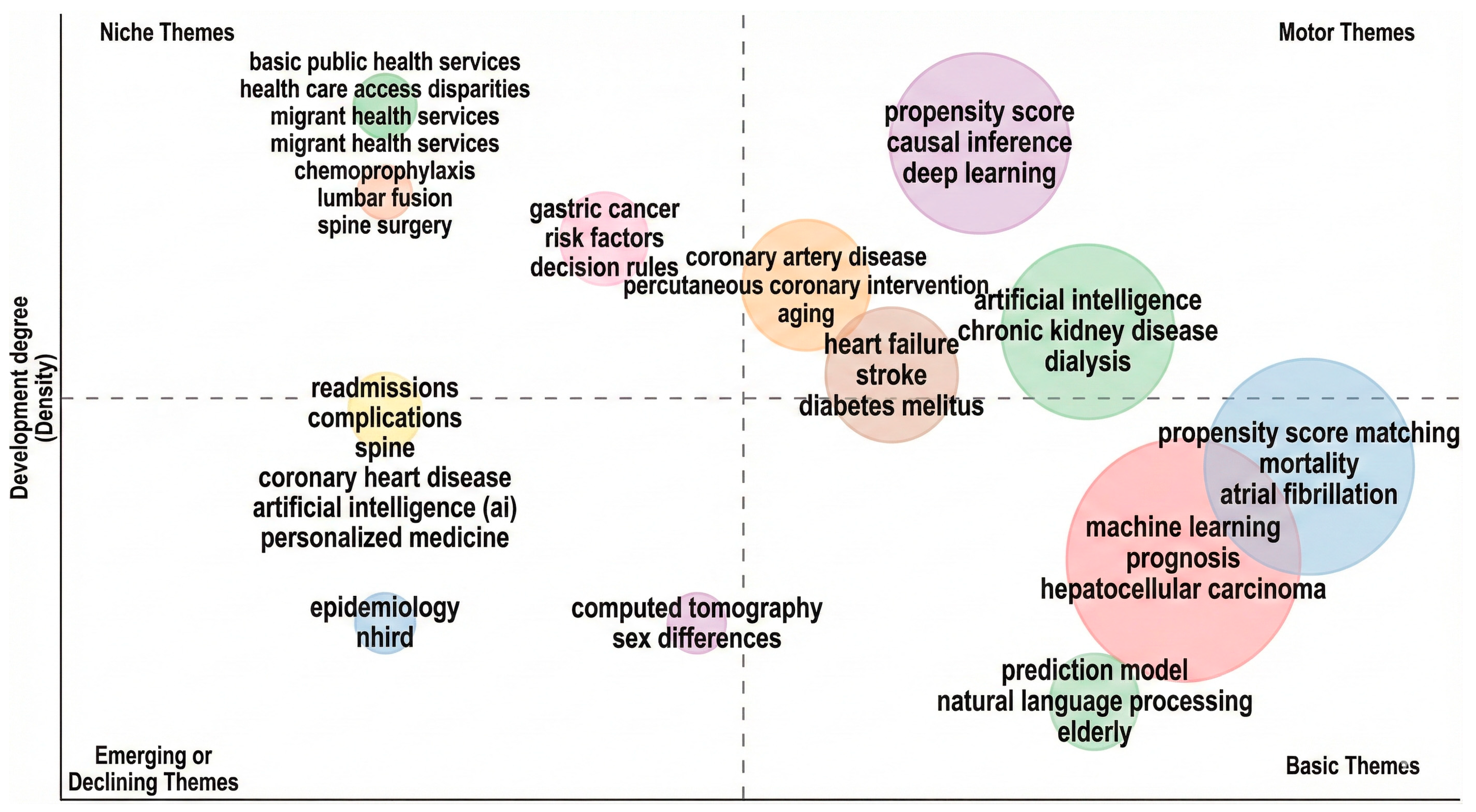

3.4. Prolific Term and Topic Trend Analysis

- Vertical Axis (Y): Development Degree (Density). This measures the internal strength and cohesion of a theme (the strength of links within the cluster).

- Horizontal Axis (X): Centrality. (While not explicitly labelled, the layout represents the theme’s external relevance or “relevance degree”). This measures the interaction between a theme and other research topics.

- Methodological Focus: There is a significant presence of PSM and AI computational methods in the “Motor” and “Basic” quadrants, specifically deep learning, machine learning, and propensity score matching.

- Clinical Applications: High-impact themes (are heavily weighted toward chronic conditions and mortality, including Stroke, Diabetes Mellitus, Atrial Fibrillation, and Hepatocellular Carcinoma.

- Thematic Transition: The cluster containing “artificial intelligence” appears in both the Emerging and Motor quadrants, suggesting a transition where generic AI research is emerging in specific sub-fields, while specialized applications (like AI in chronic kidney disease) have become “Motor” themes.

4. Discussion

- Restrict input variables in the manner to manually exclude variables that predict treatment but not the outcome to prevent the AI from creating “perfect separation” that constricts matching.

- Use AI algorithms that are mathematically tuned to achieve clinical similarity rather than just high accuracy.

- Proactively discard patients with propensity scores at the extremes to ensure matching only the patients who truly had a clinical “choice” of receiving either treatment.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dang, A. Real-World Evidence: A Primer. Pharm. Med. 2023, 37, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Lin, J.; Chi, A.; Davies, S. Practical Considerations of Utilizing Propensity Score Methods in Clinical Development Using Real-World and Historical Data. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2020, 97, 106123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, J.G.; Kraft, P.; Evans-Axelsson, S.; Hijazy, A.; Beyer, K.; De Meulder, B.; Liu, A.Q.; Golozar, A.; Harbachou, A.; Feng, Q.; et al. Real-World Evidence on Baseline Characteristics and Treatment in Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer: Findings from the PIONEER 2.0 Big Data Investigation Group. Eur. Urol. Open Sci. 2025, 81, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Antari, M.A. Artificial Intelligence for Medical Diagnostics—Existing and Future AI Technology. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artificial Intelligence Meets Medical Robotics|Science. Available online: https://www.science.org/doi/full/10.1126/science.adj3312?casa_token=HoLADs-riL4AAAAA%3AlU3aQJbwQEQy0iPYzPU33NHeoF8CLJxIq8kJonOrHDAyKUZ1yYmEgCiA1wbPSyJFsiEKks2hnpeys2U (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Bonkhoff, A.K.; Grefkes, C. Precision Medicine in Stroke: Towards Personalized Outcome Predictions Using Artificial Intelligence. Brain 2022, 145, 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briganti, G.; Le Moine, O. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine: Today and Tomorrow. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Li, X.; Gan, Y.; Han, S.; Rong, P.; Wang, W.; Li, W.; Zhou, L. Artificial Intelligence Assists Precision Medicine in Cancer Treatment. Front. Oncol. 2023, 12, 998222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muehlematter, U.J.; Daniore, P.; Vokinger, K.N. Approval of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning-Based Medical Devices in the USA and Europe (2015–2020): A Comparative Analysis. Lancet Digit. Health 2021, 3, e195–e203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shick, A.A.; Webber, C.M.; Kiarashi, N.; Weinberg, J.P.; Deoras, A.; Petrick, N.; Saha, A.; Diamond, M.C. Transparency of Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning-Enabled Medical Devices. npj Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Shen, Z.; Wu, X.; Wei, K.; Liu, Y. The Application of Artificial Intelligence in Medical Diagnostics: A New Frontier. Acad. J. Sci. Technol. 2023, 8, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Sande, D.; Van Genderen, M.E.; Smit, J.M.; Huiskens, J.; Visser, J.J.; Veen, R.E.R.; van Unen, E.; BA, O.H.; Gommers, D.; van Bommel, J. Developing, Implementing and Governing Artificial Intelligence in Medicine: A Step-by-Step Approach to Prevent an Artificial Intelligence Winter. BMJ Health Care Inform. 2022, 29, e100495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Jin, J.; Zhang, H.; Lu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, C.; Liang, Y.; Tian, S.; Zhao, Y.; Fan, H. Traumatic Brain Injury: Bridging Pathophysiological Insights and Precision Treatment Strategies. Neural Regen. Res. 2026, 21, 887–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, X.; Zheng, L.-W.; Ding, Y.; Chen, Y.-F.; Cai, Y.-W.; Wang, L.-P.; Huang, L.; Liu, C.-C.; Shao, Z.-M.; Yu, K.-D. Breast Cancer: Pathogenesis and Treatments. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katip, W.; Rayanakorn, A.; Oberdorfer, P.; Taruangsri, P.; Nampuan, T. Short versus Long Course of Colistin Treatment for Carbapenem-Resistant A. baumannii in Critically Ill Patients: A Propensity Score Matching Study. J. Infect. Public Health 2023, 16, 1249–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krenzien, F.; Schmelzle, M.; Pratschke, J.; Feldbrügge, L.; Liu, R.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, J.J.; Tan, H.-L.; Cipriani, F.; et al. Propensity Score-Matching Analysis Comparing Robotic Versus Laparoscopic Limited Liver Resections of the Posterosuperior Segments: An International Multicenter Study. Ann. Surg. 2024, 279, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langworthy, B.; Wu, Y.; Wang, M. An Overview of Propensity Score Matching Methods for Clustered Data. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2023, 32, 641–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meneguzzo, P.; Antoniades, A.; Garolla, A.; Tozzi, F.; Todisco, P. Predictors of Psychopathology Response in Atypical Anorexia Nervosa Following Inpatient Treatment: A Propensity Score Matching Study of Weight Suppression and Weight Loss Speed. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2024, 57, 1002–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.V.; Schneeweiss, S.; Franklin, J.M.; Desai, R.J.; Feldman, W.; Garry, E.M.; Glynn, R.J.; Lin, K.J.; Paik, J.; Patorno, E.; et al. Emulation of Randomized Clinical Trials with Nonrandomized Database Analyses. JAMA 2023, 329, 1376–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, P.; Liao, W.; Zhang, W.-G.; Chen, L.; Shu, C.; Zhang, Z.-W.; Huang, Z.-Y.; Chen, Y.-F.; Lau, W.Y.; Zhang, B.-X.; et al. A Prospective Study Using Propensity Score Matching to Compare Long-Term Survival Outcomes After Robotic-Assisted, Laparoscopic, or Open Liver Resection for Patients with BCLC Stage 0-A Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Ann. Surg. 2023, 277, e103–e111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jochum, F.; Dumas, É.; Gougis, P.; Hamy, A.-S.; Querleu, D.; Lecointre, L.; Gaillard, T.; Reyal, F.; Lecuru, F.; Laas, E.; et al. Survival Outcomes of Primary vs. Interval Cytoreductive Surgery for International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics Stage IV Ovarian Cancer: A Nationwide Population-Based Target Trial Emulation. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2025, 232, 194.e1–194.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Hussain, M.; Ammar Zahid, R.M.; Maqsood, U.S. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Corporate Digital Strategies: Evidence from China. Kybernetes 2025, 54, 3062–3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-B.; Bae, J.H. Effectiveness of a Novel Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Colonoscopy System for Adenoma Detection: A Prospective, Propensity Score-Matched, Non-Randomized Controlled Study in Korea. Clin. Endosc. 2025, 58, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetto, U.; Head, S.J.; Angelini, G.D.; Blackstone, E.H. Statistical Primer: Propensity Score Matching and Its Alternatives. Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. 2018, 53, 1112–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.W. Statistical Methods for Baseline Adjustment and Cohort Analysis in Korean National Health Insurance Claims Data: A Review of PSM, IPTW, and Survival Analysis with Future Directions. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2025, 40, e110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, L.; Waller, E. The Future of Health Physics: Trends, Challenges, and Innovation. Health Phys. 2025, 128, 167–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Alharbi, K.; Zhang, P.; Qin, H.; Yue, X. Bayesian Federated Causal Inference and Its Application in Manufacturing. J. Intell. Manuf. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennecken, J. Predicting Subclinical Atrial Fibrillation Using Artificial Intelligence and Validate Using Propensity-Score Matching and Explainable AI. Master’s Thesis, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2024. Available online: https://studenttheses.uu.nl/handle/20.500.12932/47904 (accessed on 25 January 2026).

- Ishiyama, M.; Kudo, S.; Misawa, M.; Mori, Y.; Maeda, Y.; Ichimasa, K.; Kudo, T.; Hayashi, T.; Wakamura, K.; Miyachi, H.; et al. Impact of the Clinical Use of Artificial Intelligence–Assisted Neoplasia Detection for Colonoscopy: A Large-Scale Prospective, Propensity Score–Matched Study (with Video). Gastrointest. Endosc. 2022, 95, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Choi, J.S.; Kim, K.; Ko, E.S.; Ko, E.Y.; Han, B.-K. Effect of Artificial Intelligence–Based Computer-Aided Diagnosis on the Screening Outcomes of Digital Mammography: A Matched Cohort Study. Eur. Radiol. 2023, 33, 7186–7198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosperi, M.; Ghosh, S.; Chen, Z.; Salemi, M.; Lyu, T.; Zhao, J.; Bian, J. Causal AI with Real World Data: Do Statins Protect from Alzheimer’s Disease Onset? In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Medical and Health Informatics, Kyoto, Japan, 14–16 May 2021; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 296–303. [Google Scholar]

- Karim, M.E. Can Supervised Deep Learning Architecture Outperform Autoencoders in Building Propensity Score Models for Matching? BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2024, 24, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lourenço, L.; Weber, L.; Garcia, L.; Ramos, V.; Souza, J. Machine Learning Algorithms to Estimate Propensity Scores in Health Policy Evaluation: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whata, A.; Chimedza, C. Evaluating Uses of Deep Learning Methods for Causal Inference. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 2813–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokol, P.; Kokol, M.; Zagoranski, S. Machine Learning on Small Size Samples: A Synthetic Knowledge Synthesis. Sci. Prog. 2022, 105, 00368504211029777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokol, P. Synthetic Knowledge Synthesis in Hospital Libraries. J. Hosp. Libr. 2024, 24, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software Survey: VOSviewer, a Computer Program for Bibliometric Mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. Bibliometrix: An R-Tool for Comprehensive Science Mapping Analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, P.C. Comparing Paired vs. Non-paired Statistical Methods of Analyses When Making Inferences About Absolute Risk Reductions in Propensity-Score Matched Samples. Stat. Med. 2011, 30, 1292–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, P.C.; Small, D.S. The Use of Bootstrapping When Using Propensity-Score Matching Without Replacement: A Simulation Study. Stat. Med. 2014, 33, 4306–4319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scimago Journal & Country Rank. Available online: https://www.scimagojr.com/ (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Islam, N.; Islam, S.; Roy, P.B. A Bibliometric Technique for Analyzing Trends in Public Health Research. Data Sci. Inf. 2024, 4, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Shen, H.; Xu, Q.; Tu, C.; Yang, R.; Liu, T.; Tang, H.; Miao, Z.; Zhang, J. Evaluating Coronary Arteries and Predicting MACEs Using CCTA in Lung Cancer Patients Receiving Chemotherapy or Chemoradiotherapy. Radiother. Oncol. 2024, 200, 110498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.; Choi, Y.-J.; Kim, B.S.; Rhee, T.-M.; Lee, H.-J.; Han, K.-D.; Park, J.-B.; Na, J.O.; Kim, Y.-J.; Lee, H.; et al. Comparative Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes Patients Taking Dapagliflozin Versus Empagliflozin: A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2023, 22, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squiccimarro, E.; Lorusso, R.; Consiglio, A.; Labriola, C.; Haumann, R.G.; Piancone, F.; Speziale, G.; Whitlock, R.P.; Paparella, D. Impact of Inflammation After Cardiac Surgery on 30-Day Mortality and Machine Learning Risk Prediction. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2025, 39, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngufor, C.; Zhang, N.; Van Houten, H.K.; Holmes, D.R.; Graff-Radford, J.; Alkhouli, M.; Friedman, P.A.; Noseworthy, P.A.; Yao, X. Causal Machine Learning for Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 2025, 11, 977–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettus, J.; Roussel, R.; Liz Zhou, F.; Bosnyak, Z.; Westerbacka, J.; Berria, R.; Jimenez, J.; Eliasson, B.; Hramiak, I.; Bailey, T.; et al. Rates of Hypoglycemia Predicted in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes on Insulin Glargine 300 U/ML Versus First- and Second-Generation Basal Insulin Analogs: The Real-World LIGHTNING Study. Diabetes Ther. 2019, 10, 617–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Gupta, M.P.; Dekker, A.L.; Bermejo, I.; Kar, S. Development and Validation of Multicenter Study on Novel Artificial Intelligence Based Cardiovascular Risk Score (AICVD). Res. Sq. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Chao, Y.; Xu, M.; Geng, X.; Hu, X. Development of a machine learning model for predicting 28-day mortality of septic patients with atrial fibrillation. Shock 2023, 59, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, H.; Ran, X.; Li, S.; Zhang, Q. Dyslipidemia Versus Obesity as Predictors of Ischemic Stroke Prognosis: A Multi-Center Study in China. Lipids Health Dis. 2024, 23, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, H.; Pan, K.; Wang, J.; Lin, J. Association between Neutrophil Percentage-to-Albumin Ratio and Breast Cancer in Adult Women in the US: Findings from the NHANES. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1533636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Winhusen, T.J.; Gorenflo, M.; Ghitza, U.E.; Davis, P.B.; Kaelber, D.C.; Xu, R. Repurposing Ketamine to Treat Cocaine Use Disorder: Integration of Artificial Intelligence-Based Prediction, Expert Evaluation, Clinical Corroboration and Mechanism of Action Analyses. Addiction 2023, 118, 1307–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pundi, K.; Fan, J.; Kabadi, S.; Din, N.; Blomström-Lundqvist, C.; Camm, A.J.; Kowey, P.; Singh, J.P.; Rashkin, J.; Wieloch, M.; et al. Dronedarone Versus Sotalol in Antiarrhythmic Drug-Naive Veterans with Atrial Fibrillation. Circ. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2023, 16, 456–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Li, C.; Liu, M.; Wang, Y.; Feng, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, W.; Wu, F.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, X. Prognostic Models Using Machine Learning Algorithms and Treatment Outcomes of Occult Breast Cancer Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.W.; Park, Y.-L.; Lee, E.-G.; Chae, H.; Park, P.; Choi, D.-W.; Choi, Y.H.; Hwang, J.; Ahn, S.; Kim, K.; et al. Mortality Prediction Modeling for Patients with Breast Cancer Based on Explainable Machine Learning. Cancers 2024, 16, 3799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Gong, N.; Li, D.; Deng, Y.; Chen, J.; Luo, D.; Zhou, W.; Xu, K. Identifying Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients with Survival Benefits from Surgery Combined with Chemotherapy: Based on Machine Learning Model. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 20, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Liu, Z.; Xiao, L.; Xia, Y.; Huang, J.; Luo, H.; Zong, Z.; Zhu, Z. Clinical Significance of Serum CA125, CA19-9, CA72-4, and Fibrinogen-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Gastric Cancer with Peritoneal Dissemination. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Xiang, C.; Wu, J.; Teng, Y.; Wu, Z.; Wang, R.; Lu, B.; Zhan, Z.; Wu, H.; Zhang, J. Tongue Coating Bacteria as a Potential Stable Biomarker for Gastric Cancer Independent of Lifestyle. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2021, 66, 2964–2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makhnevich, A.; Perrin, A.; Talukder, D.; Liu, Y.; Izard, S.; Chiuzan, C.; D’Angelo, S.; Affoo, R.; Rogus-Pulia, N.; Sinvani, L. Thick Liquids and Clinical Outcomes in Hospitalized Patients with Alzheimer Disease and Related Dementias and Dysphagia. JAMA Intern. Med. 2024, 184, 778–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Digumarthi, V.; Amin, T.; Kanu, S.; Mathew, J.; Edwards, B.; Peterson, L.A.; Lundy, M.E.; Hegarty, K.E. Preoperative Prediction Model for Risk of Readmission After Total Joint Replacement Surgery: A Random Forest Approach Leveraging NLP and Unfairness Mitigation for Improved Patient Care and Cost-Effectiveness. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2024, 19, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, S.D.; Yu, R. Re-Evaluating the Impact of Hormone Replacement Therapy on Heart Disease Using Match-Adaptive Randomization Inference. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.01330. [Google Scholar]

- Feller, D.J.; Zucker, J.; Yin, M.T.; Gordon, P.; Elhadad, N. Using Clinical Notes and Natural Language Processing for Automated HIV Risk Assessment. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2018, 77, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoccali, C.; Tripepi, G. Clinical Trial Emulation in Nephrology. J. Nephrol. 2024, 38, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.S.; Raman, V.K.; Zhang, S.; Sheriff, H.M.; Fonarow, G.C.; Heidenreich, P.A.; Faselis, C.; Lam, P.H.; Morgan, C.J.; Moore, H.; et al. Renin Angiotensin Inhibition and Lower Risk of Kidney Failure in Patients with Heart Failure. Am. J. Med. 2025, 138, 1384–1393.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, K.; Seeman, T.E.; Horwich, T.; Budoff, M.J.; Watson, K.E. Heterogeneity in the Association between the Presence of Coronary Artery Calcium and Cardiovascular Events: A Machine-Learning Approach in the MESA Study. Circulation 2023, 147, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietropaoli, D.; Monaco, A.; D’Aiuto, F.; Aguilera, E.M.; Ortu, E.; Giannoni, M.; Czesnikiewicz-Guzik, M.; Guzik, T.J.; Ferri, C.; Del Pinto, R.D. Active Gingival Inflammation Is Linked to Hypertension. J. Hypertens. 2020, 38, 2018–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, S.; Chen, L.; Lin, H.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhong, F.; Liu, D. Prediction Model for Delayed Behavior of Early Ambulation After Surgery for Varicose Veins of the Lower Extremity: A Prospective Case-Control Study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2024, 105, 1908–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, S.; Kapeleshh, K.S.; Dovgan, E.; Luštrek, M.; Gradišek Piletič, B.; Srinivasan, K.; Li, Y.-C.; Gradišek, A.; Syed-Abdul, S. Machine Learning Prediction Models for Chronic Kidney Disease Using National Health Insurance Claim Data in Taiwan. Healthcare 2021, 9, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Bian, J.; Guo, Y.; Prosperi, M. Deep Propensity Network Using a Sparse Autoencoder for Estimation of Treatment Effects. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2021, 28, 1197–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Luo, W.; Zhu, J. Development and External Validation of Interpretable Machine Learning Models for Personalized Multiple Treatment Recommendations in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2026, 206, 106160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weymann, D.; Chan, B.; Regier, D.A. Genetic Matching for Time-Dependent Treatments: A Longitudinal Extension and Simulation Study. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2023, 23, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Shi, Y.; He, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, H.; Yang, J.; Leng, Y. Abdominal Physical Examinations in Early Stages Benefit Critically Ill Patients without Primary Gastrointestinal Diseases: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1338061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Yang, J.; Lu, J.; Zhou, Z.; Huang, K.; Zhang, S.; Yuan, G.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Z. Ureteral Calculi Lithotripsy for Single Ureteral Calculi: Can DNN-Assisted Model Help Preoperatively Predict Risk Factors for Sepsis? Eur. Radiol. 2022, 32, 8540–8549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colaneri, M.; Fama, F.; Fassio, F.; Holmes, D.; Scaglione, G.; Mariani, C.; Galli, L.; Lai, A.; Antinori, S.; Gori, A.; et al. Impact of Early Antiviral Therapy on SARS-CoV-2 Clearance Time in High-Risk COVID-19 Subjects: A Propensity Score Matching Study. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 149, 107265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Ali, H.; Shah, Z. Identifying the Role of Vision Transformer for Skin Cancer—A Scoping Review. Front. Artif. Intell. 2023, 6, 1202990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Country | Rank All Disciplines | Rank in Medicine | Rank in Artificial Intelligence | Rank in Statistics and Probability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| United states | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| South Korea | 13 | 14 | 12 | 16 |

| Japan | 5 | 5 | 4 | 10 |

| Germany | 4 | 4 | 6 | 4 |

| France | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 |

| Canada | 9 | 8 | 9 | 8 |

| Italy | 8 | 6 | 8 | 5 |

| India | 6 | 9 | 3 | 7 |

| Journal Name | SNIP | Quarter | Research Area |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frontiers in Oncology | 0.831 | 2. | Cancer Research, Oncology |

| Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine | 0.742 | 2. | Cardiology and Cardiovascular Medicine |

| BMC Infectious Diseases | 1.106 | 1. | Infectious Diseases |

| Frontiers in Public Health | 0.938 | 2. | Public Health, Environmental and Occupational Health |

| Journal of Clinical Medicine | 1.022 | 1. | Medicine (all) |

| JMIR Medical Informatics | 1.035 | 2. | Health Information Management Health Informatics |

| Cancers | 1.030 | 2. | Cancer Research Oncology |

| Frontiers in Pharmacology | 0.999 | 1. | Pharmacology Pharmacology (medical) |

| BMC Public Health | 1.386 | 1. | Public Health, Environmental and Occupational Health |

| European Radiology | 1.775 | 1. | Radiology, Nuclear Medicine and Imaging |

| Frontiers in Endocrinology | 1.122 | 2. | Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism |

| Frontiers in Medicine | 0.879 | 1. | Medicine (all) |

| Theme | Prolific Author’s Keywords Association Sub-Networks | Publications Describing AI Use in Combination with PSM | Publications Describing PSM Use in AI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prediction Blue (14 author keywords) | Cardiovascular diseases—Diabetes mellitus Atrial fibrillation—sepsis-prediction | [43,44,45] [46] | [47,48] [49,50] |

| Cancer management Red (15 author keywords) | Breast cancer—SEER Hepatocellular carcinoma—SEER—chemotherapy-survival Gastric cancer—random forest Natural language model, prediction modelling | [51] [52,53] | [54,55] [56] [57,58] [59,60] |

| Diagnosing Green (14 author keywords) | Coronary heart diseases—diagnosis Diagnosis—Intensive care unit—Public health Chronic kidney disease—Electronic health record | [61] [62,63] [64] | [65,66] [67] [68] |

| Deep learning Yellow (7 author keywords) | Casual inference—Big data—deep learning Monte Carlo simulation Computer tomography—deep learning | [69,70] [71] | [72] [73] |

| Theme | Authors Keywords Association Sub-Networks | The Synthesis of High Impact Publications Identified in Table 3 |

|---|---|---|

| Prediction | Cardiovascular diseases—Diabetes mellitus | Binomial regression models and random forest regression was performed on a dataset of high-risk COVID-19 subjects (inclusion criteria: age over 65 years old, presence of solid or haematological cancer, chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease, chronic lung disease, uncontrolled diabetes, neurological disease, cardiovascular disease, obesity, cerebrovascular disease or being immunocompromised (AIDS, solid organ or blood stem cell transplantation, and all conditions requiring use of corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive medications)) after performing PSM based on being early treated or not [74]. In a cohort study cardiovascular outcomes between new and existing users of dapagliflozin and empagliflozin in type 2 diabetes patients were compared. Using a Korean cohort dataset, the authors employed a nearest-neighbours machine learning approach for propensity score matching prior to statistical analysis [44]. The LIGHTNING study modelled, predicted, and compared hypoglycaemia rates of people with type 2 diabetes, comparing patients using first- or second-generation insulin preparations. During analysis, authors first used conventional PSM and then advanced machine learning [47]. A large-scale Indian patient database was analyzed using the Spearman correlation coefficient method and deep learning to build a hazard model, which was used to predict CVD events and their time of occurrence that reportedly had a good performance rate. PSM was used to match patients with and without CVD [48]. The utility of coronary computed tomography angiography was investigated in detecting cancer treatment-related coronary artery impairments and predicting major adverse cardiovascular events in lung cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy or chemo-radiotherapy. Their methodology involved (1) AI-driven image recognition for initial assessment, (2) PSM mach patients with and without carcinoma, and (3) Cox regression modelling to evaluate differences survival rates [43]. Authors examined systemic inflammatory response syndrome impact on 30-day mortality post-cardiac surgery and developed predictive machine learning models. PSM was used to balance the training set [45]. |

| Atrial fibrillation—sepsis-prediction | A model to predict the risk of mortality in septic patients with atrial fibrillation was developed using different ML algorithms. They used PSM to reduce the imbalance between the external validation and internal validation data sets [49]. Five different ML algorithms were used to determine whether dyslipidaemia or obesity contributes more towards unfavourable clinical outcomes in patients suffering a first-ever ischemic stroke. PSM was employed to ascertain associations between indicators and prognosis [50]. PSM and a causal machine learning framework were applied to predict heterogeneous treatment effects of LAAO versus DOAC in atrial fibrillation patients, enabling AI-driven individualized benefit estimation for improved patient selection and clinical decision-making [46]. | |

| Cancer management | Breast cancer—SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) database | SEER database was used to identify the prognostic variables for patients with occult breast cancer, which is an uncommon malignant tumour for which the prognosis and treatment remain a controversial topic. Cox regression analysis was performed to construct prognostic models with the help of six machine learning algorithms to predict overall survival. The authors further examined the impact of chemotherapy and surgery on survival outcomes in occult breast cancer patients stratified by molecular subtype, utilizing Kaplan–Meier survival analysis and propensity score matching. These findings were subsequently validated through subgroup Cox regression analysis [54]. South Korean investigators used machine learning-based risk factor detection and breast cancer mortality prediction with the Shappley Additive Explanation, which is an explainable artificial intelligence technique, to identify and interpret key features that have a significant impact on breast cancer mortality. To enhance the robustness and generalizability of their primary findings and balance the baseline covariates, they employed an exposure-driven 1:3 PSM analysis while minimizing a logistic regression model with the implications of potential confounders [55]. A total of 18,726 participants were examined for assessing breast cancer prevalence and neutrophil-percentage-to-albumin ratio. Study revealed a significant positive association, potentially mediated by sex hormone levels, validated through advance multivariate, subgroup, and PSM [51]. |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma—SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) database—chemotherapy-survival | Patients diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma were identified in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database. The authors first conducted univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses to assess prognostic factors, then developed a 5-year survival risk prediction model using classical decision tree methodology. To address potential confounding variables related to chemotherapy administration, PSM was used for both high-risk and low-risk patient cohorts [56]. | |

| Gastric cancer—random forests | Clinical data from 391 gastric cancer patients were analyzed using PSM. The authors subsequently performed both univariate and multivariate conditional logistic regression analyses. Their methodology further incorporated classification tree analysis to establish decision rules, followed by random forest algorithm implementation to extract significant risk factors for peritoneal dissemination in gastric cancer [57]. The association of the tongue coating microbiota with the serum metabolic features and inflammatory cytokines in gastric cancer patients was explored to identify potential non-invasive biomarker for diagnosing gastric cancer. The tongue coating microbiota was profiled by 16S rRNA and 18S rRNA genes sequencing technology in the original population with 181 patients and 112 healthy controls. The PSM was used to eliminate potential confounders, including age, gender, and six lifestyle factors, and a matching population was created. Random forest model was used for diagnosis classification [58]. | |

| Natural language model prediction modelling | An innovative integrated strategy was developed to identify FDA-approved drugs for repurposing in cocaine use disorder treatment. The study combined AI-driven drug prediction with clinical validation through the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network, incorporating expert panel review and mechanistic action analysis. Based on combined AI prioritization and clinical expertise, ketamine emerged as the top candidate for further evaluation. The team conducted electronic health record analysis comparing outcomes in patients prescribed ketamine (for anaesthesia/depression) against PSM identified controls receiving alternative treatments [52]. PSM was used to balance the covariates across two groups of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia patients with oropharyngeal during hospitalization, whether at least 75% of their hospital diet consisted of a thick liquid diet or a thin liquid diet. Machine learning was used to predict hospital outcomes such as mortality, length of stay, and complications [59]. Data from 38,581 shoulder and hip replacement patients was analyzed to develop a random forest model predicting 30-day post-discharge outcomes (emergency department visits, unplanned readmissions, or discharge to skilled nursing facilities). The study incorporated 98 features spanning laboratory results, diagnoses, vital signs, medications, and utilization history. Clinical BERT-finetuned NLP model was used to generate risk scores from clinical notes. To address potential biases, the methodology combined PSM with comprehensive feature bias analysis, implementing Fairlearn toolkit’s threshold optimization to mitigate gender and payer-related prediction disparities [75]. Natural language processing on clinical records of antiarrhythmic drug-naïve patients from the Veterans Health Administration database was used to identify and compare baseline left ventricular ejection fraction between treatments with different drugs. PSM was used on patient demographics, comorbidities, and medications, as well as Cox regression to compare treatments. A falsification analysis with non-plausible outcomes was performed to evaluate residual confounding [53]. | |

| Diagnosing | Coronary heart diseases-diagnosis | A study examined whether coronary artery calcium predictive value across demographic subgroups in the Multi-Ethnic Study of cohort. After using PSM, the team employed causal forest modelling to (1) quantify heterogeneity in CAC-CVD associations, and (2) predict individualized 10-year CVD risk increases. These machine learning estimates were subsequently benchmarked against absolute 10-year risks calculated via 2013 ACC/AHA pooled cohort equations [65]. A recent study explored whether gingival bleeding—a simple clinical indicator of periodontal disease—might serve as a marker for hypertension. Given the established link between cardiovascular diseases and systemic inflammation, with periodontitis potentially exacerbating this inflammatory burden, researchers analyzed data from 5396 adults aged ≥30 years who completed both blood pressure assessments and periodontal exams. Using survey-based PSM that accounted for key confounders shared by hypertension and periodontal disease, authors created matched cohorts with and without gingival bleeding. The analysis employed generalized additive models adjusted for inflammatory markers to evaluate associations between bleeding gums and both systolic blood pressure and uncontrolled hypertension. Further stratification by periodontal status (healthy, gingivitis, stable periodontitis, unstable periodontitis) provided additional insights, while machine learning techniques helped determine variable importance in these relationships [66]. A new algorithm was developed to improve propensity score matching by correctly sampling treatment distributions while accounting for “Z-dependence.” Unlike fixed-pair designs, it addresses how post-treatment matching changes with each permutation, ensuring valid inference where traditional methods fail due to fluid matched sets [61]. |

| Diagnosing | Diagnosis—Intensive care unit- Public health | A study evaluated the added value of natural language processing for enhancing HIV diagnosis prediction models. Their study included 181 HIV-positive patients, along with 543 PSM selected HIV-negative controls. Authors extracted structured EHR data (demographics, laboratory results, diagnosis codes) and unstructured clinical notes from the pre-diagnosis period. Next, they developed three machine learning models: (1) a baseline model using only structured EHR data, (2) baseline plus NLP-derived topics, and (3) baseline plus NLP-extracted clinical keywords. Results demonstrated that incorporating NLP features significantly improved predictive accuracy for HIV risk assessment [62]. A review paper claims that trial emulation with PMS use in observational studies represents a significant advancement in epidemiology and can support improving public health outcomes. However, traditional PSM techniques face challenges like data quality, unmeasured confounding, and implementation complexity that could be overcome with machine learning techniques to address unmeasured confounding [63]. In a recent study, information from selected participants divided into a normal and delayed ambulation group before surgery was collected and followed up until the day after surgery. PSM was applied to all participants by type of surgery and anaesthesia. All the characteristics in the two groups were compared using logistic regression, back propagation neural network, and decision tree models [67]. |

| Chronic kidney disease—Electronic health record | A machine learning model to predict incidents of chronic kidney disease (6–12 months before clinical onset was developed using Taiwan’s National Health Insurance claims data. The study employed PSM to select 18,000 CKD cases and 72,000 matched controls, analyzing two years of demographic, medication, and comorbidity history for each subject. Among various algorithms tested, convolutional neural networks demonstrated superior predictive performance [68]. In a PSM study of 168,860 veterans with heart failure phenotyped by AI, high-dose RAS inhibitors were associated with a lower 5-year risk of kidney failure compared to low doses. This benefit was primarily driven by patients with existing chronic kidney disease, regardless of ejection fraction, potentially informing future clinical guidelines [64]. | |

| Deep Learning | Casual inference—deep learning | A large-scale analysis of ICU patients without primary gastrointestinal diseases using the MIMIC-IV database was performed to evaluate the prognostic value of abdominal physical examinations (palpation and auscultation). Patients were stratified based on examination status, with 28-day mortality as the primary endpoint. The researchers employed multiple analytical approaches: Cox proportional hazards models, PSM, and inverse probability treatment weighting. Six machine learning algorithms—Random Forest, Gradient Boosting Decision Trees, AdaBoost, Extra Trees, Bagging, and Multilayer Perceptron—were subsequently implemented to develop predictive models for in-hospital mortality [72]. To reduce the underlying bias in observational studies, Ghosh et al. [71] developed a new deep learning architecture for propensity score matching and counterfactual prediction. Machine learning enhanced propensity score estimation by improving covariate balance, reducing bias in observational studies, and enabling robust causal inference, thereby advancing methodological rigour in treatment effect in patients with non-small lung cancer, by analysis across complex, high-dimensional healthcare and social science datasets [70]. |

| Monte Carlo simulation | To address the imitations of manual PSM by developing a machine learning enhanced genetic matching approach that automatically optimizes covariate history balancing. Through Monte Carlo simulation studies, the authors demonstrated superior performance of their automated method compared to traditional manual matching techniques [71]. | |

| Computer tomography—deep learning | Radiomics and deep learning approaches were investigated for predicting sepsis risk following stone removal procedures in ureteral calculus patients. After using PSM, they developed (1) a radiomics model for sepsis prediction, and (2) an enhanced deep learning model to boost predictive accuracy. LASSO regression identified 26 key predictive variables. The deep neural network (DNN) implementation showed improved AUC in internal validation, with subsequent external validation confirming model generalizability by addressing overfitting concerns [73]. |

| Concepts, AI Algorithms and Techniques | n | Medical Applications | n | Diagnoses | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Machine Learning (Generic) | 66 | Risk Assessment | 14 | Cardiovascular Diseases | 18 |

| Artificial Intelligence (Generic) | 23 | Prognosis | 11 | Heart Diseases | 12 |

| Deep Learning | 11 | Prediction Model | 11 | Kidney Diseases | 11 |

| Random Forest | 6 | Survival Analysis | 11 | Diabetes | 9 |

| Decision Tree | 5 | Mortality | 10 | Coronary Diseases | 7 |

| NLP | 5 | Decision Support | 6 | Gastric Cancer | 6 |

| Big Data | 3 | Health Services | 6 | Hepatocellular Carcinoma | 6 |

| SHAP/Explainable AI | 2 | Nomogram | 5 | Atrial Fibrillation | 6 |

| Feature Selection | 2 | Epidemiology | 5 | COVID-19 | 6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kokol, P.; Žlahtič, B.; Blažun Vošner, H.; Završnik, J.; Završnik, T. Symbiosis in Health: The Powerful Alliance of AI and Propensity Score Matching in Real World Medical Data Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 1524. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031524

Kokol P, Žlahtič B, Blažun Vošner H, Završnik J, Završnik T. Symbiosis in Health: The Powerful Alliance of AI and Propensity Score Matching in Real World Medical Data Analysis. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(3):1524. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031524

Chicago/Turabian StyleKokol, Peter, Bojan Žlahtič, Helena Blažun Vošner, Jernej Završnik, and Tadej Završnik. 2026. "Symbiosis in Health: The Powerful Alliance of AI and Propensity Score Matching in Real World Medical Data Analysis" Applied Sciences 16, no. 3: 1524. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031524

APA StyleKokol, P., Žlahtič, B., Blažun Vošner, H., Završnik, J., & Završnik, T. (2026). Symbiosis in Health: The Powerful Alliance of AI and Propensity Score Matching in Real World Medical Data Analysis. Applied Sciences, 16(3), 1524. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031524