Memory Retrieval After an Acute Academic Stressor: An Exploratory Analysis of Anticipatory Cortisol and DHEA Responses

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (i)

- To examine the psychobiological (state anxiety, negative and positive affect, cortisol and DHEA) responses to an ecological stressor (i.e., a real-life academic examination). State anxiety, as well as negative and positive affect, refer to temporary emotional states and were included specifically to validate the academic examination as an effective psychological stressor.

- (ii)

- To investigate the visual memory performance for both emotional and neutral material after the stressor.

- (iii)

- To explore whether the anticipatory hormonal responses were related to emotional and neutral visual memory performance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.2.1. Acquisition Session

2.2.2. Recall Session

2.3. Questionnaires and Measures

2.3.1. Psychological Response

State Anxiety

Negative and Positive Affect

2.3.2. Memory Assessment

Free Recall

Recognition

2.4. Biochemical Analyses

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Session Differences in Psychological Responses

3.1.1. State Anxiety

3.1.2. Negative and Positive Affect

3.2. Hormonal Response

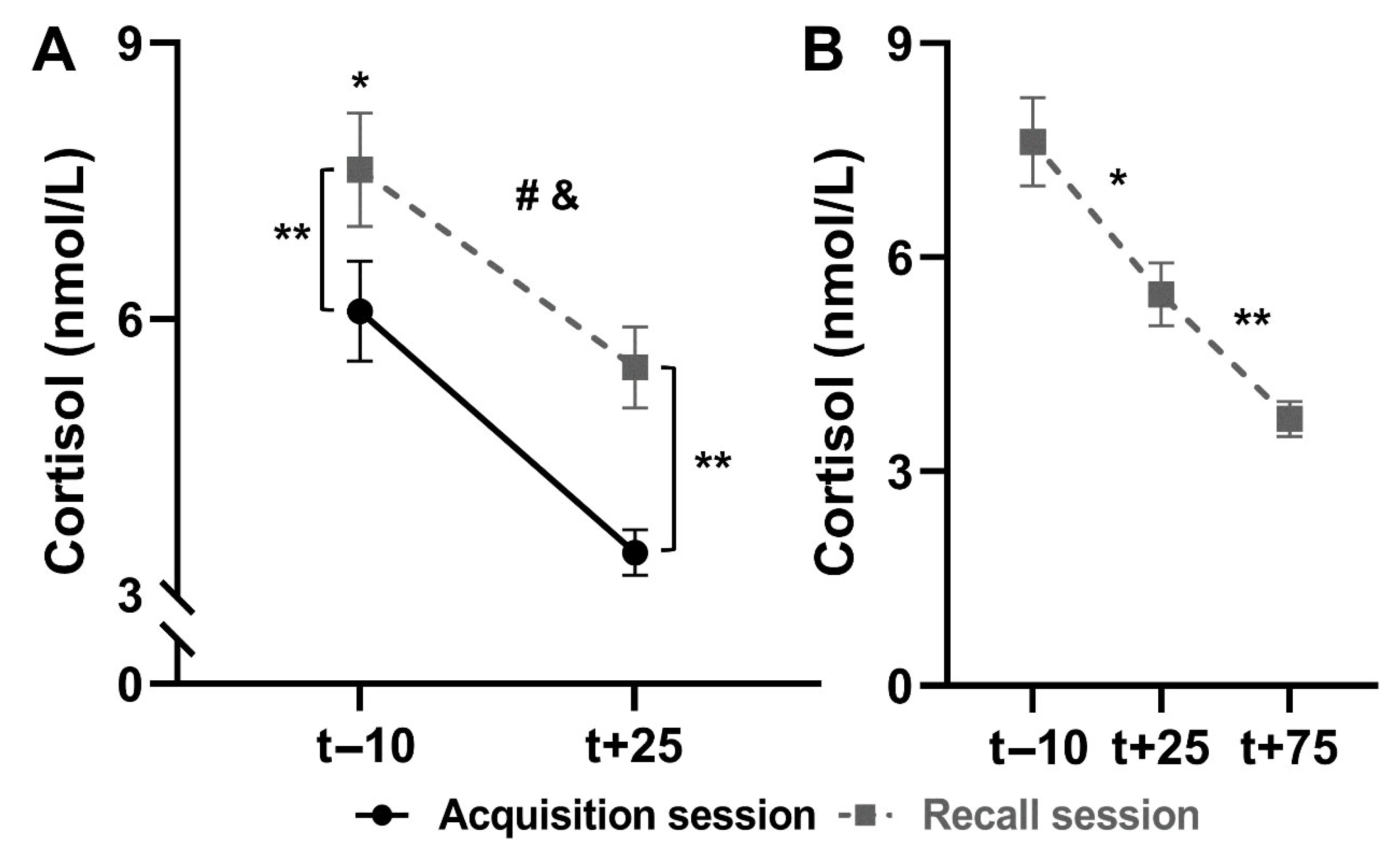

3.2.1. Salivary Cortisol

Comparison Between Sessions

Recall Session

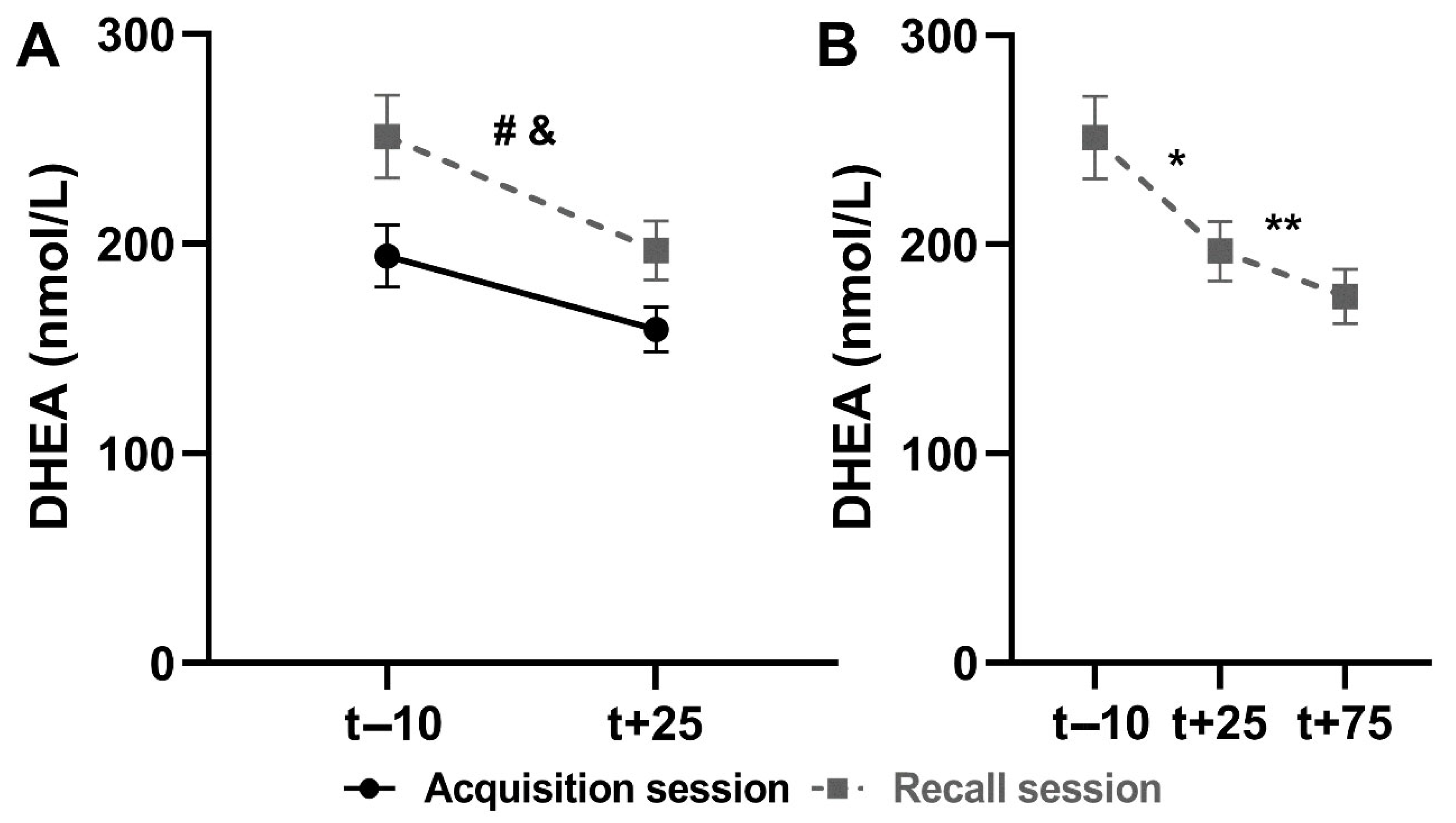

3.2.2. Salivary DHEA

Comparison Between Sessions

Recall Session

3.3. Emotional Ratings of Picture Stimuli

3.3.1. Valence Ratings

3.3.2. Arousal Ratings

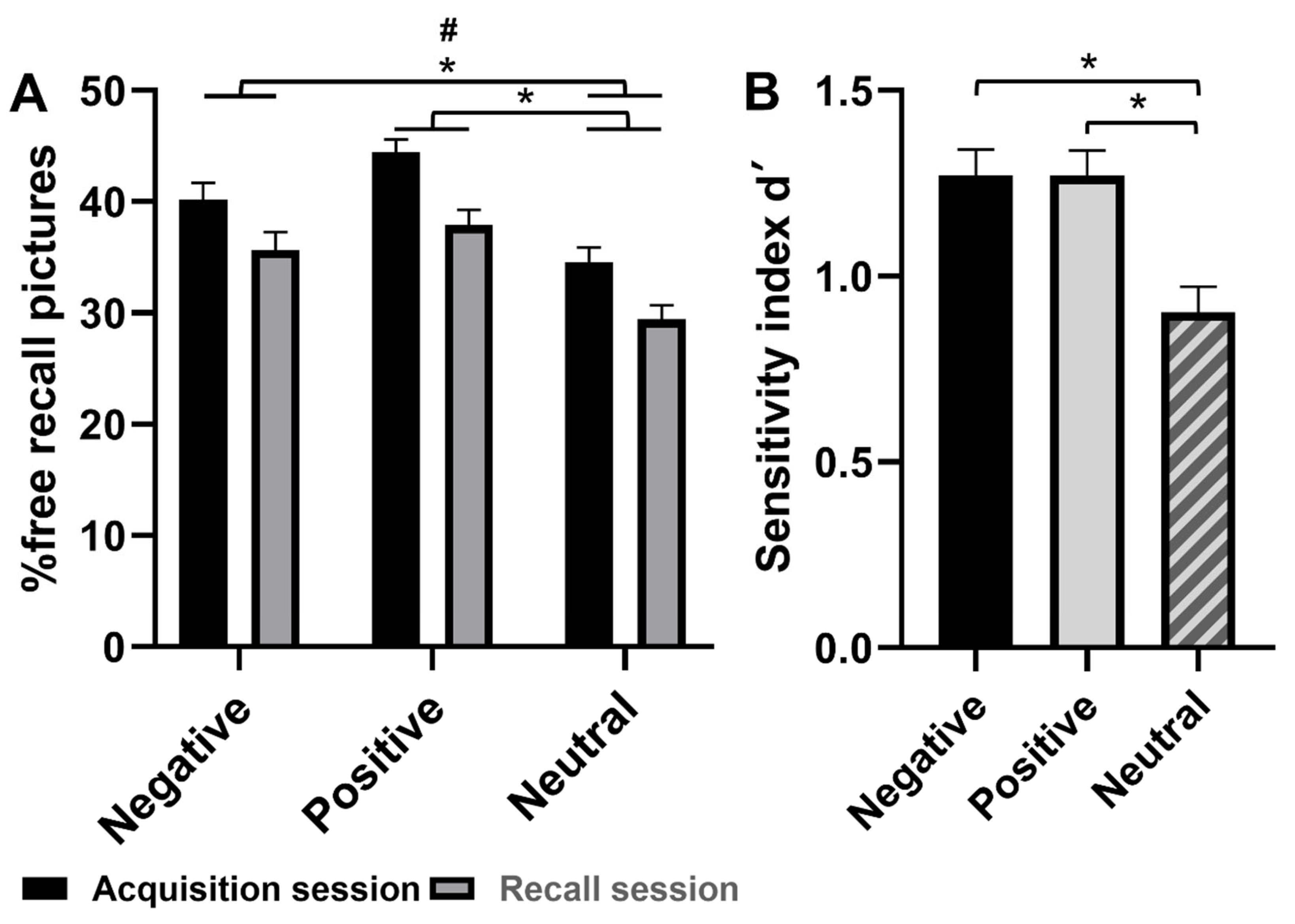

3.4. Memory Performance

3.4.1. Free Recall Performance

3.4.2. Recognition Performance

3.5. Exploratory Analysis of the Relationship Between Pre-Examination Hormonal Levels and Memory Performance

3.5.1. Delayed Free Recall

3.5.2. Recognition

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DHEA | Dehydroepiandrosterone |

| HPA | Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal (axis) |

| NMDA | N-methyl-D-aspartate (receptor) |

| SAM | Self-Assessment Manikin |

| STAI-S | State-Trait Anxiety Inventory—State version |

| PANAS | Positive and Negative Affect Schedule |

| IAPS | International Affective Picture System |

| SES | Subjective Educational and Socioeconomic Status |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| MCP | Menstrual Cycle Phase |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| SEM | Standard Error of the Mean |

References

- Campbell, J.; Ehlert, U. Acute psychosocial stress: Does the emotional stress response correspond with physiological responses? Psychoneuroendocrinology 2012, 37, 1111–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickerson, S.S.; Kemeny, M.E. Acute stressors and cortisol responses: A theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychol. Bull. 2004, 130, 355–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garces-Arilla, S.; Fidalgo, C.; Mendez-Lopez, M.; Osma, J.; Peiro, T.; Salvador, A.; Hidalgo, V. Female students’ personality and stress response to an academic examination. Anxiety Stress Coping 2024, 37, 460–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, T.; Gouveia, M.J.; Oliveira, R.F. Testosterone responsiveness to winning and losing experiences in female soccer players. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2009, 34, 1056–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taverniers, J.; Smeets, T.; Lo Bue, S.; Syroit, J.; Van Ruysseveldt, J.; Pattyn, N.; von Grumbkow, J. Visuo-spatial path learning, stress, and cortisol secretion following military cadets’ first parachute jump: Effect of increasing task complexity. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2011, 11, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupert, S.D.; Neubauer, A.B.; Scott, S.B.; Hyun, J.; Sliwinski, M.J. Back to the future: Examining age differences in processes before stressor exposure. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2019, 74, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, S.D.; Buchanan, T.W.; Stansfield, R.B.; Bechara, A. Effects of anticipatory stress on decision making in a gambling task. Behav. Neurosci. 2007, 121, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Raedt, R.; Hooley, J.M. The role of expectancy and proactive control in stress regulation: A neurocognitive framework for regulation expectation. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 45, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottaviani, C. Brain-heart interaction in perseverative cognition. Psychophysiology 2018, 55, e13082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, A.; Costa, R. Coping with competition: Neuroendocrine responses and cognitive variables. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2009, 33, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich-Lai, Y.M.; Herman, J.P. Neural regulation of endocrine and autonomic stress responses. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2009, 10, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.D.; Conley, A.J. Nonhuman primates as models for human adrenal androgen production: Function and dysfunction. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2008, 10, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theorell, T. Anabolism and catabolism—Antagonistic partners in stress and strain. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2008, 6, 136–143. [Google Scholar]

- Sollberger, S.; Ehlert, U. How to use and interpret hormone ratios. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2016, 63, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutheil, F.; de Saint Vincent, S.; Pereira, B.; Schmidt, J.; Moustafa, F.; Charkhabi, M.; Bouillon-Minois, J.B.; Clinchamps, M. DHEA as a biomarker of stress: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 688367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltzer, E. An ecological approach for investigations of the anticipatory cortisol stress response. Biol. Psychol. 2022, 175, 108428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garces-Arilla, S.; Mendez-Lopez, M.; Fidalgo, C.; Salvador, A.; Hidalgo, V. Examination-related anticipatory levels of dehydroepiandrosterone and cortisol predict positive affect, examination marks and support-seeking in college students. Stress 2024, 27, 2330009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preuß, D.; Schoofs, D.; Schlotz, W.; Wolf, O.T. The stressed student: Influence of written examinations and oral presentations on salivary cortisol concentrations in university students. Stress 2010, 13, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irshad, L.; Faustini, S.; Evans, L.; Drayson, M.T.; Campbell, J.P.; Heaney, J.L.J. Salivary free light chains as a new biomarker to measure psychological stress: The impact of a university exam period on salivary immunoglobulins, cortisol, DHEA and symptoms of infection. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2020, 122, 104912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, V.; Almela, M.; Villada, C.; van der Meij, L.; Salvador, A. Verbal performance during stress in healthy older people: Influence of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and cortisol reactivity. Biol. Psychol. 2020, 149, 107786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Vale, S.; Selinger, L.; Martins, J.M.; Gomes, A.C.; Bicho, M.; Do Carmo, I.; Escera, C. The relationship between dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), working memory and distraction—A behavioral and electrophysiological approach. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e104869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwabe, L. Memory under stress: From single systems to network changes. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2017, 45, 478–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwabe, L.; Joëls, M.; Roozendaal, B.; Wolf, O.T.; Oitzl, M.S. Stress effects on memory: An update and integration. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2012, 36, 1740–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roozendaal, B. Stress and memory: Opposing effects of glucocorticoids on memory consolidation and memory retrieval. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2002, 78, 578–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurice, T.; Grégoire, C.; Espallergues, J. Neuro(active)steroids actions at the neuromodulatory sigma1 (σ1) receptor: Biochemical and physiological evidences, consequences in neuroprotection. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2006, 84, 581–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerchner, G.A.; Nicoll, R.A. Silent synapses and the emergence of a postsynaptic mechanism for LTP. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008, 9, 813–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sripada, R.K.; Marx, C.E.; King, A.P.; Rajaram, N.; Garfinkel, S.N.; Abelson, J.L.; Liberzon, I. DHEA enhances emotion regulation neurocircuits and modulates memory for emotional stimuli. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013, 38, 1798–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimonides, V.G.; Khatibi, N.H.; Svendsen, C.N.; Sofroniew, M.V.; Herbert, J. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and DHEA-sulfate (DHEAS) protect hippocampal neurons against excitatory amino acid-induced neurotoxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 1852–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, E.; Casarotti, D.; Muzzoni, B.; Albertelli, N.; Cravello, L.; Fioravanti, M.; Solerte, S.B.; Magri, F. Age-related changes of the adrenal secretory pattern: Possible role in pathological brain aging. Brain Res. Rev. 2001, 37, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, G.S.; Sazma, M.A.; McCullough, A.M.; Yonelinas, A.P. The effects of acute stress on episodic memory: A meta-analysis and integrative review. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, T.W.; Tranel, D. Stress and emotional memory retrieval: Effects of sex and cortisol response. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2008, 89, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domes, G.; Heinrichs, M.; Rimmele, U.; Reichwald, U.; Hautzinger, M. Acute stress impairs recognition for positive words—Association with stress-induced cortisol secretion. Stress 2004, 7, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oei, N.Y.L.; Everaerd, W.T.A.M.; Elzinga, B.M.; Van Well, S.; Bermond, B. Psychosocial stress impairs working memory at high loads: Association with cortisol levels and memory retrieval. Stress 2006, 9, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tollenaar, M.S.; Elzinga, B.M.; Spinhoven, P.; Everaerd, W.A.M. The effects of cortisol increase on long-term memory retrieval during and after acute psychosocial stress. Acta Psychol. 2008, 127, 542–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schönfeld, P.; Ackermann, K.; Schwabe, L. Remembering under stress: Different roles of autonomic arousal and glucocorticoids in memory retrieval. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2014, 39, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoofs, D.; Wolf, O.T. Stress and memory retrieval in women: No strong impairing effect during the luteal phase. Behav. Neurosci. 2009, 123, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoladz, P.R.; Kalchik, A.E.; Hoffman, M.M.; Aufdenkampe, R.L.; Burke, H.M.; Woelke, S.A.; Pisansky, J.M.; Talbot, J.N. Brief, pre-retrieval stress differentially influences long-term memory depending on sex and corticosteroid response. Brain Cogn. 2014, 85, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klier, C.; Buratto, L.G. Stress and long-term memory retrieval: A systematic review. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2020, 42, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, V.; Pulopulos, M.M.; Puig-Perez, S.; Espin, L.; Gomez-Amor, J.; Salvador, A. Acute stress affects free recall and recognition of pictures differently depending on age and sex. Behav. Brain Res. 2015, 292, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, T.W. Retrieval of emotional memories. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 133, 761–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roozendaal, B.; McEwen, B.S.; Chattarji, S. Stress, memory and the amygdala. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2009, 10, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.M.; Elliott, G.; Hughes, G.I.; Feinn, R.S.; Brunyé, T.T. Acute stress improves analogical reasoning: Examining the roles of stress hormones and long-term memory. Think. Reason. 2020, 27, 294–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merz, C.J.; Wolf, O.T. Examination of cortisol and state anxiety at an academic setting with and without oral presentation. Stress 2015, 18, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verschoor, E.; Markus, C.R. Affective and neuroendocrine stress reactivity to an academic examination: Influence of the 5-HTTLPR genotype and trait neuroticism. Biol. Psychol. 2011, 87, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehringer, A.; Schwabe, L.; Schachinger, H. A combination of high stress-induced tense and energetic arousal compensates for impairing effects of stress on memory retrieval in men. Stress 2010, 13, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhlmann, S.; Piel, M.; Wolf, O.T. Impaired memory retrieval after psychosocial stress in healthy young men. J. Neurosci. 2005, 25, 2977–2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merz, C.J.; Hagedorn, B.; Wolf, O.T. An oral presentation causes stress and memory impairments. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019, 104, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeets, T. Acute stress impairs memory retrieval independent of time of day. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2011, 36, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espín, L.; Marquina, M.; Hidalgo, V.; Salvador, A.; Gómez-Amor, J. No effects of psychosocial stress on memory retrieval in non-treated young students with Generalized Social Phobia. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2016, 73, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strahler, J.; Skoluda, N.; Kappert, M.B.; Nater, U.M. Simultaneous measurement of salivary cortisol and alpha-amylase: Application and recommendations. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 83, 657–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, N.E.; Epel, E.S.; Castellazzo, G.; Ickovics, J.R. Subjective SES Scale; APA PsycTests: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; Database record. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila, J.; Sanchez, M. El sistema internacional de imágenes afectivas (IAPS): Adaptación española. Segunda parte. Rev. Psicol. Gen. Apl. 2001, 54, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, P.J.; Bradley, M.M.; Cuthbert, B.N. Technical Manual and Affective Ratings; NIMH Center for the Study of Emotion and Attention: Gainesville, FL, USA, 1997; Volume 1, pp. 3–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, M.M.; Lang, P.J. Measuring emotion: The Self-Assessment Manikin and the Semantic Differential. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 1994, 25, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillén-Riquelme, A.; Buela-Casal, G. Actualización psicométrica y funcionamiento diferencial de los ítems en el State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). Psicothema 2011, 23, 510–515. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Spielberger, C.D. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory: A Comprehensive Bibliography; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Sandín, B.; Chorot, P.; Lostao, L.; Joiner, T.E.; Santed, M.A.; Valiente, R.M. The PANAS scales of positive and negative affect: Factor analytic validation and cross-cultural convergence. Psicothema 1999, 11, 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanislaw, H.; Todorov, N. Calculation of signal detection theory measures. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 1999, 31, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudielka, B.M.; Hellhammer, D.H.; Wüst, S. Why do we respond so differently? Reviewing determinants of human salivary cortisol responses to challenge. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2009, 34, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björntorp, P.; Rosmond, R. Obesity and cortisol. Nutrition 2000, 16, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, L.G.; Levens, S.M.; Bennett, J.M. Stressful life events, relationship stressors, and cortisol reactivity: The moderating role of suppression. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2018, 89, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangler, G. Psychological and physiological responses during an exam and their relation to personality characteristics. Psychoneuroendocrinology 1997, 22, 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulme, P.A.; French, J.A.; Agrawal, S. Changes in diurnal salivary cortisol levels in response to an acute stressor in healthy young adults. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2011, 17, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringeisen, T.; Lichtenfeld, S.; Becker, S.; Minkley, N. Stress experience and performance during an oral exam: The role of self-efficacy, threat appraisals, anxiety, and cortisol. Anxiety Stress Coping 2019, 32, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghan, F.; Khodaei, F.; Afshar, L.; Shojaei, F.K.; Poorhakimi, E.; Soori, R.; Fatolahi, H.; Azarbayjani, M.A. Effect of competition on stress salivary biomarkers in elite and amateur female adolescent inline skaters. Sci. Sports 2019, 34, e37–e44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberbeck, R.; Benschop, R.J.; Jacobs, R.; Hosch, W.; Jetschmann, J.U.; Schurmeyer, T.H.; Schmidt, R.E.; Schedlowski, M. Endocrine mechanisms of stress-induced DHEA-secretion. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 1998, 21, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Zheng, P. Dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate: Action and mechanism in the brain. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2012, 24, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maninger, N.; Wolkowitz, O.M.; Reus, V.I.; Epel, E.S.; Mellon, S.H. Neurobiological and neuropsychiatric effects of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and DHEA sulfate (DHEAS). Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2009, 30, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | |

|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | |

| Age—M (SD, range) | 18.60 (1.055, 18–25) |

| SES—M (SD, range) | 6.68 (0.468, 6–7) |

| Physiological | |

| BMI—n (%) | |

| Underweight | 3 (3.8%) |

| Normal weight | 67 (84.8%) |

| Overweight | 9 (11.4%) |

| MCP—n (%) | |

| Menstruation | 17 (30.9%) |

| Follicular | 8 (14.5%) |

| Ovulation | 8 (14.5%) |

| Luteal | 14 (25.5%) |

| Premenstrual | 8 (14.5%) |

| Nulliparous—n (%) | 69 (100%) |

| Oral contraceptives—n (%) | 14 (20.3%) |

| Negative life events—n (%) | 10 (12.7%) |

| Predictors | Criterion: % Total Delayed Free Recall Performance | |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | R2 = 0.058, Adj R2 = −0.010, p = 0.617 | |

| β (95% CI) | p | |

| Cortisol (AS_t − 10) | −0.058 (−9.103, 5.436) | 0.617 |

| Step 2 | R2 = 0.111, Adj R2 = 0.087, ∆R2 = 0.108, p = 0.003 * | |

| β (95% CI) | p | |

| Cortisol (AS_t − 10) | 0.279 (−1.007, 18.788) | 0.078 |

| Cortisol (RS_t − 10) | −0.470 (−26.515, −5.420) | 0.003 * |

| Criterion: % Total delayed free recall performance | ||

| Step 1 | R2 = 0.003, Adj R2 = −0.024, p = 0.887 | |

| β (95% CI) | p | |

| C/D ratio (AS_t − 10) | −0.012 (−18.726, 16.803) | 0.914 |

| Step 2 | R2 = 0.119; Adj. R2 = 0.095; ΔR2 = 0.118; p = 0.002 * | |

| β (95% CI) | p | |

| C/D ratio (AS_t − 10) | 0.322 (1.641, 48.489) | 0.036 |

| C/D ratio (RS_t − 10) | −0.480 (−69.085, −15.815) | 0.002 * |

| Criterion: % Negative pictures remembered in delayed free recall | ||

| Step 1 | R2 = 0.001, Adj R2 = −0.012, p = 0.778 | |

| β (95% CI) | p | |

| Cortisol (AS_t − 10) | 0.032 (−9.679, 12.878) | 0.778 |

| Step 2 | R2 = 0.100, Adj R2 = 0.076, ∆R2 = 0.099, p = 0.005 | |

| β (95% CI) | p | |

| Cortisol (AS_t − 10) | 0.355 (2.106, 32.969) | 0.026 |

| Cortisol (RS_t − 10) | −0.451 (−40.174, −7.286) | 0.005 † |

| Step 1 | R2 = 0.002; Adj. R2 = −0.011; p = 0.665 | |

| β (95% CI) | p | |

| C/D ratio (AS_t − 10) | 0.050 (−21.492, 33.500) | 0.665 |

| Step 2 | R2 = 0.114; Adj. R2 = 0.090; ΔR2 = 0.111; p = 0.003 * | |

| β (95% CI) | p | |

| C/D ratio (AS_t − 10) | 0.374 (8.717, 81.509) | 0.016 |

| C/D ratio (RS_t − 10) | −0.466 (−105.173, −22.402) | 0.003 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Garces-Arilla, S.; Hidalgo, V.; Fidalgo, C.; Peiró, T.; Salvador, A.; Mendez-Lopez, M. Memory Retrieval After an Acute Academic Stressor: An Exploratory Analysis of Anticipatory Cortisol and DHEA Responses. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 1306. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031306

Garces-Arilla S, Hidalgo V, Fidalgo C, Peiró T, Salvador A, Mendez-Lopez M. Memory Retrieval After an Acute Academic Stressor: An Exploratory Analysis of Anticipatory Cortisol and DHEA Responses. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(3):1306. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031306

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarces-Arilla, Sara, Vanesa Hidalgo, Camino Fidalgo, Teresa Peiró, Alicia Salvador, and Magdalena Mendez-Lopez. 2026. "Memory Retrieval After an Acute Academic Stressor: An Exploratory Analysis of Anticipatory Cortisol and DHEA Responses" Applied Sciences 16, no. 3: 1306. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031306

APA StyleGarces-Arilla, S., Hidalgo, V., Fidalgo, C., Peiró, T., Salvador, A., & Mendez-Lopez, M. (2026). Memory Retrieval After an Acute Academic Stressor: An Exploratory Analysis of Anticipatory Cortisol and DHEA Responses. Applied Sciences, 16(3), 1306. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031306