1. Introduction

The increasing digitalization of healthcare systems has led to exponential growth in the volume and complexity of biomedical data, underscoring the need for interoperability among heterogeneous medical devices and software platforms [

1,

2]. Modern hospital infrastructure integrates equipment from multiple vendors, each with proprietary data formats and communication protocols. This lack of interoperability can hinder clinical decision-making, especially in time-critical scenarios.

Health Level Seven (HL7) standards provide a well-established framework for the structured exchange of medical information between electronic systems [

3,

4]. The transition from the traditional HL7 v2.x architecture to the Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) model introduces a RESTful, web-based approach supporting modern data formats such as JSON and XML [

5]. FHIR’s RESTful design and modular resources have been extensively analyzed by Bender and Sartipi [

6], confirming its suitability for lightweight interoperability. FHIR enables flexible, scalable communication between devices and healthcare information systems, facilitating seamless integration of physiological monitoring data, laboratory results, and patient records [

7]. Expanded technical documentation on developer-oriented FHIR implementation is provided in Grieve’s foundational work [

8]. This standard also enables semantic interoperability, allowing different systems to interpret biomedical information consistently and independently of vendor-specific implementations. Semantic harmonization across heterogeneous systems has been a central objective in modern health informatics [

9]. Broader methodological perspectives on semantic interoperability have been synthesized in recent reviews [

10].

Recent advances in the Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) have further expanded this vision by connecting sensors, edge devices, and cloud infrastructure to enable continuous acquisition and analysis of physiological parameters [

11,

12]. The multilayer IoMT architecture—comprising perception, network, and application layers—has been systematically defined in several high-impact surveys [

13]. Additional systematic reviews highlight the rapid expansion of IoMT architectures and their clinical applicability [

14].

Within IoMT architectures, the perception layer captures raw biomedical signals, the network layer ensures wireless communication via Wi-Fi, Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE), or ZigBee, and the application layer manages storage, visualization, and analytics through databases and artificial intelligence methods [

15,

16]. Such integration aligns with the FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) principles outlined in Wilkinson et al. [

17], which emphasize semantic interoperability and structured metadata across biomedical data ecosystems. These requirements have been clarified in recent analyses of FAIR implementation pathways [

18]. Moreover, the growing demand for remote monitoring and telemedicine—accelerated by the post-pandemic digitalization of healthcare—underscores the need for open, interoperable biomedical data frameworks.

Several case studies have explored IoMT-based acquisition platforms for specific physiological parameters, particularly blood pressure estimation from PPG signals [

19] and secure telemetry pipelines for biomedical monitoring [

20]; FAIR-aligned data-management frameworks relevant to interoperable medical ecosystems are discussed in [

17]. MQTT-based secure telemetry systems for real-time biomedical monitoring have been explored in recent implementations. However, most of these implementations rely on proprietary middleware or commercial cloud infrastructures, which hinder reproducibility and cost-effective deployment. The present case study was therefore selected to demonstrate that a fully open-source stack, built entirely from off-the-shelf components, can achieve comparable real-time performance and semantic interoperability without dependence on closed ecosystems.

Despite these technological advances, most hospital networks still rely on wired connections and proprietary middleware, which limits scalability and reproducibility [

21]. Existing implementations of IoMT-based acquisition systems using MQTT transport and HL7 FHIR encoding have been documented in several interoperability-focused studies [

7,

11,

12,

15], highlighting both architectural patterns and integration constraints across heterogeneous healthcare infrastructures. Such limitations restrict flexibility, interoperability, and validation across diverse environments.

The present study addresses these challenges by designing and validating a low-cost, fully open-source biomedical data-acquisition system compliant with the HL7 FHIR standards [

22]. The proposed solution enables secure, wireless transmission of physiological data, full semantic interoperability, and real-time visualization within a distributed monitoring framework [

23,

24]. The ESP32 microcontroller was selected for its dual-core architecture, integrated Wi-Fi and Bluetooth connectivity, and widespread adoption in biomedical and educational research, providing a cost-effective and flexible foundation for IoMT prototyping. Its originality lies in implementing a complete end-to-end data integration chain—from sensor acquisition to open-source visualization—based entirely on standardized protocols and open technologies [

25].

In comparison with widely adopted interoperability frameworks—SMART on FHIR [

7], HAPI FHIR servers [

26], and Open mHealth ecosystems [

27]—the present work provides an entirely on-premise, MQTT-based implementation that achieves real-time acquisition and HL7 FHIR-compliant encoding using only open-source components. Practical deployment considerations for HAPI FHIR servers have been reported in large-scale clinical integration studies [

28]. Recent mobile health applications illustrate hybrid Open mHealth–FHIR pipelines for distributed sensing [

29].

Unlike these frameworks, which typically rely on cloud services or heavyweight middleware, the proposed architecture emphasizes local deployment, lightweight transport, and reproducibility for laboratory-scale IoMT prototyping. This comparative positioning clarifies the contribution of the present framework relative to existing SMART-on-FHIR, HAPI FHIR, and Open mHealth pipelines.

The main contributions of this study are: (1) the development of a dual-node biomedical data acquisition system using HL7 FHIR; (2) its integration within an open-source IoT environment for end-to-end interoperability; and (3) validation of real-time data flow with sub-second latency.

This paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents the system architecture and implementation details;

Section 3 describes the case study and validation results;

Section 4 discusses the system-level implications; and

Section 5 concludes with perspectives for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. System Architecture

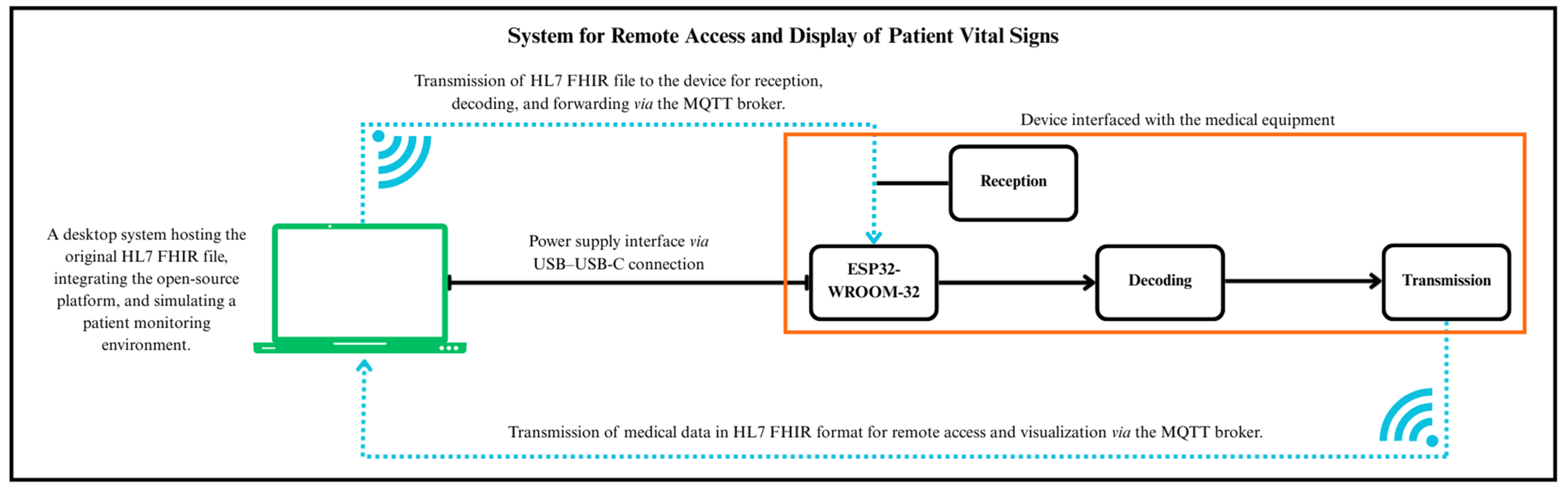

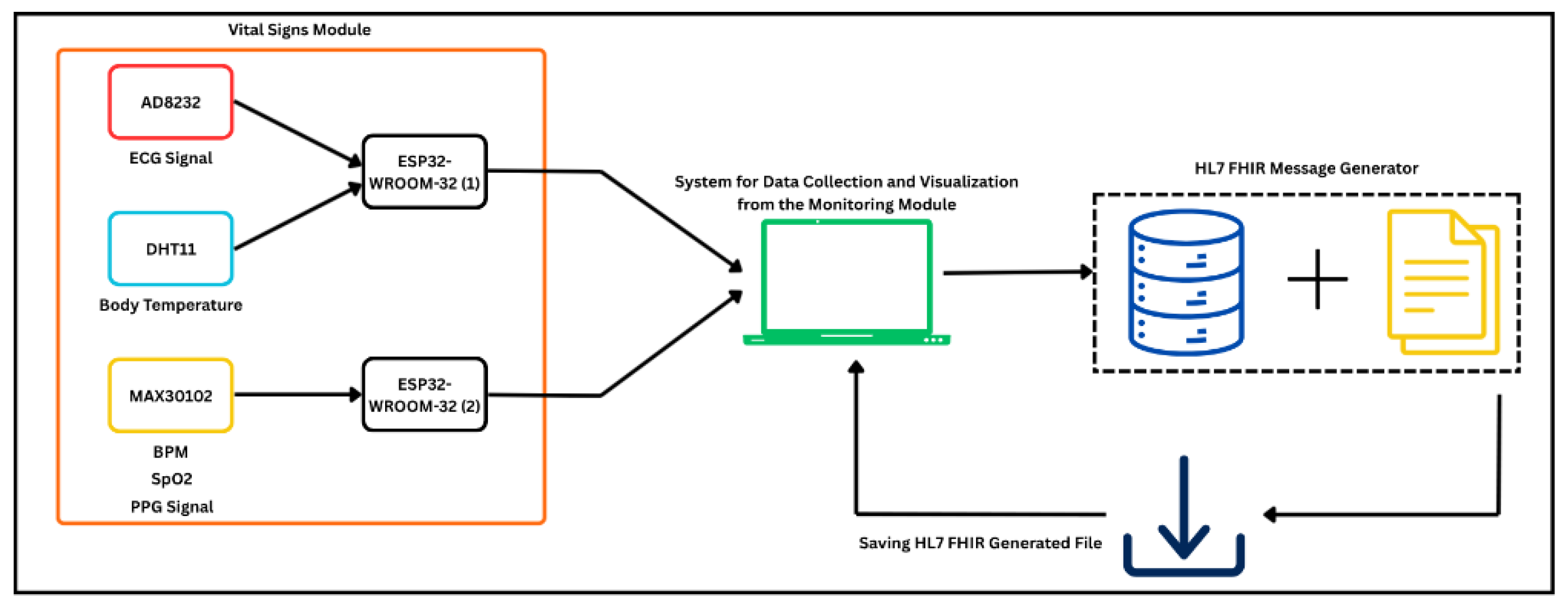

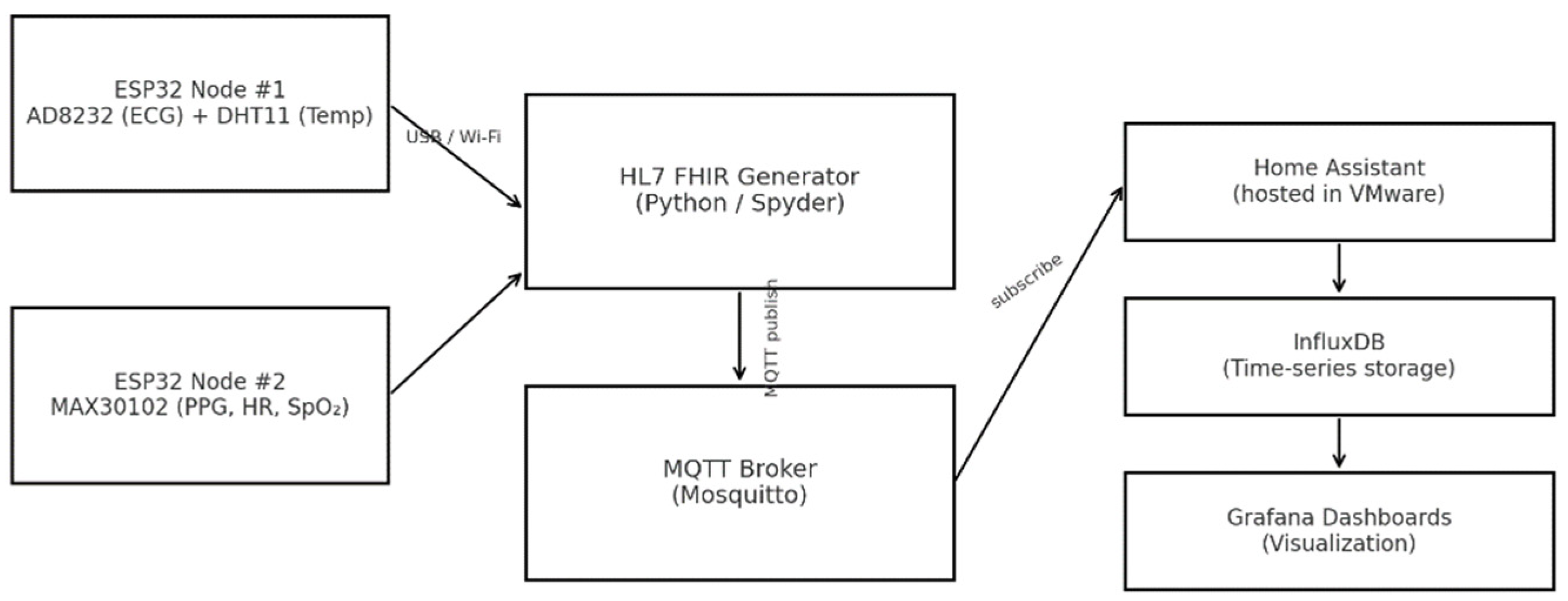

The proposed system was designed as an integrated hardware–software framework for real-time biomedical signal acquisition and wireless data transfer, fully compliant with HL7 FHIR communication standards. Its architecture (

Figure 1) consists of three functional layers: acquisition, communication, and visualization.

At the acquisition level, an ESP32-WROOM-32 microcontroller (Espressif Systems, Shanghai, China) was selected due to its dual-core architecture, embedded Wi-Fi/BLE interfaces, and compatibility with open-source firmware development environments [

16]. The device operates as a local gateway, decoding physiological data from connected medical modules and converting them into standardized HL7 FHIR “Observation” resources.

The communication layer relies on the MQTT protocol for low-latency telemetry and lightweight message transport, using a Mosquitto MQTT Broker (Eclipse Foundation, Ottawa, ON, Canada) configured with TLS encryption and credential-based authentication [

25]. Authentication is achieved through username–password credentials and TLS-based encryption, ensuring secure interoperability among system components [

12].

At the visualization layer, time-series data are stored in InfluxDB and rendered through Grafana dashboards, providing high-resolution monitoring and advanced analytical capabilities for real-time physiological tracking [

15,

30].

The overall data flow—from sensor acquisition through MQTT transmission to database storage and visualization—is illustrated in

Figure 1, which presents a three-layer architecture connecting the biomedical acquisition front-end to the open-source analytics environment.

2.2. HL7 FHIR Data Structure and Processing

The transmitted data follow the FHIR Observation resource model, selected for its structured representation of physiological signals and compatibility with RESTful communication. Each Observation entity includes metadata such as patient identifiers, device references, acquisition timestamps, and structured waveform descriptors, in accordance with the official HL7 FHIR specification [

31].

For electrocardiographic (ECG) monitoring, the valueSampledData element was used to encode waveform samples as JSON numerical sequences, along with attributes such as the sampling period, scaling factor, and physical units. The following conversion formula was applied for transforming raw integer values into corresponding physiological quantities:

where V

raw represents the digitized input value, V

offset the reference origin, and F

scale the conversion factor specified in the HL7 resource structure. In our AD8232 configuration, V

offset = 2048 (12-bit ADC midpoint), F

scale = 0.00047 mV/LSB, corresponding to the AD8232 ECG analog front-end (Analog Devices, Wilmington, MA, USA) gain of 110 and the ESP32 ADC reference of 3.3 V.

This approach ensures compatibility with standards-compliant monitoring systems. It enables future integration of multiple physiological parameters—such as oxygen saturation, respiratory rate, or body temperature—using the same FHIR data schema.

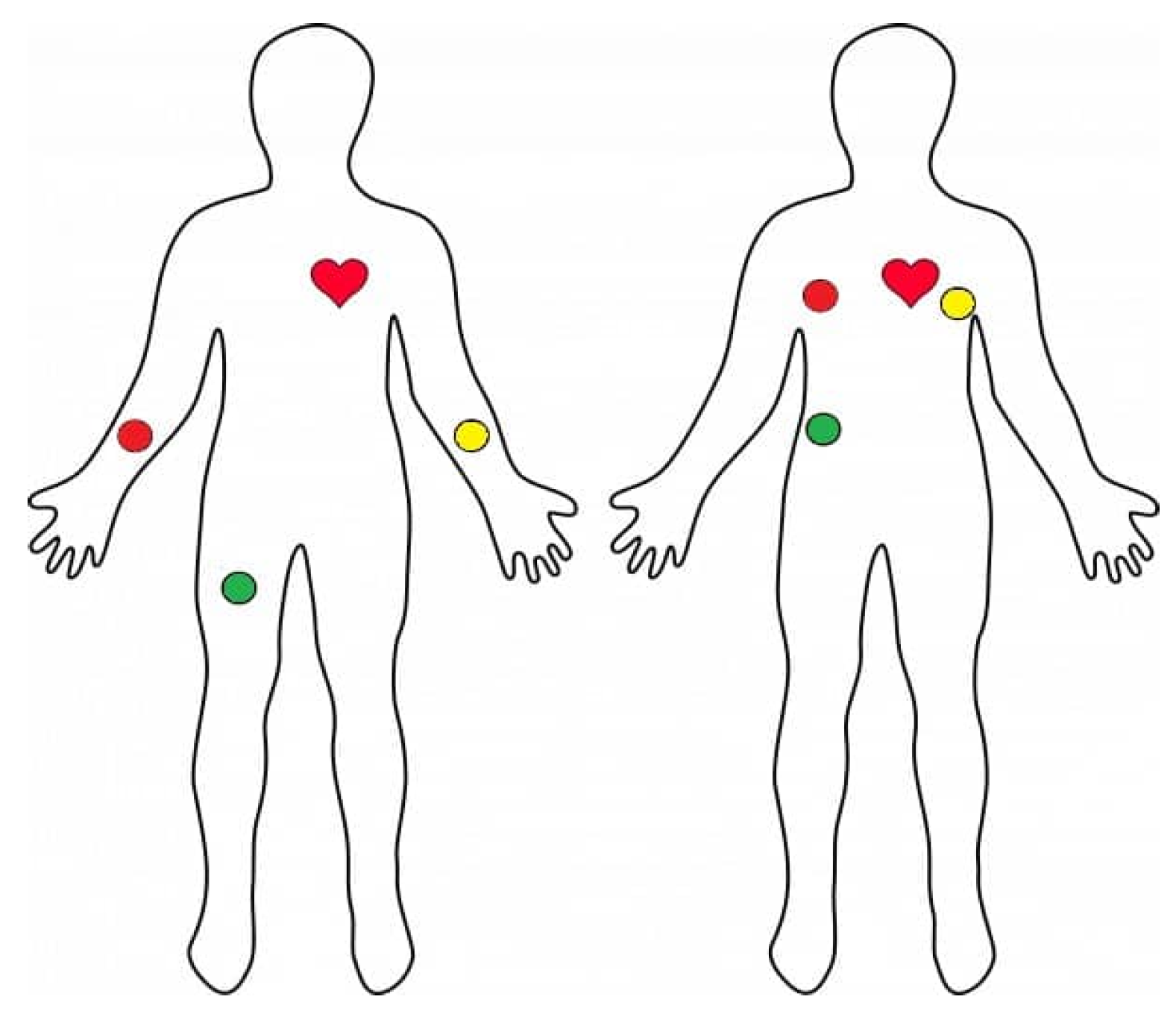

The electrode placement used for single-lead ECG acquisition is illustrated in

Figure 2, corresponding to a standard Lead II configuration commonly adopted in low-cost wearable systems.

The signal acquisition and message-generation processes were mapped into a logical workflow in which raw analog data are converted into HL7 FHIR Observations and transmitted to the integration platform. This logical flow will be detailed in the case study section (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

A representative HL7 FHIR Observation JSON excerpt, illustrating the encoding of waveform and scalar elements in the valueSampledData structure and the use of standardized UCUM units, is provided in the

Supplementary Materials to support reproducibility. ECG signals were mapped to waveform categories defined in IEEE 11073-10101-2004 [

32], the reference standard that formalizes nomenclature for physiological waveforms and underpins the mapping used in FHIR Waveform profiles.

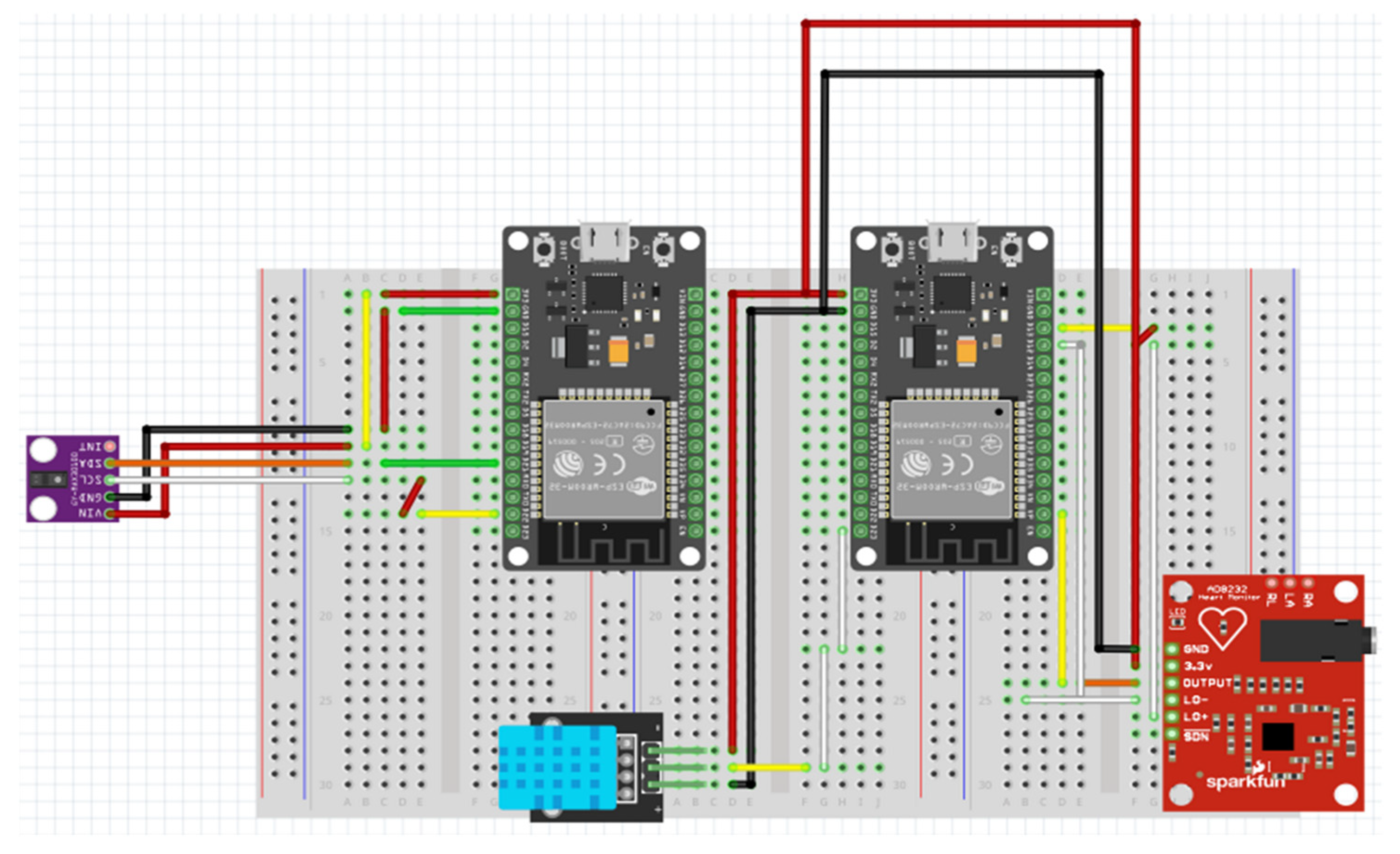

The implemented acquisition and monitoring module is shown in

Figure 3, which presents the logical structure of the multi-sensor front-end.

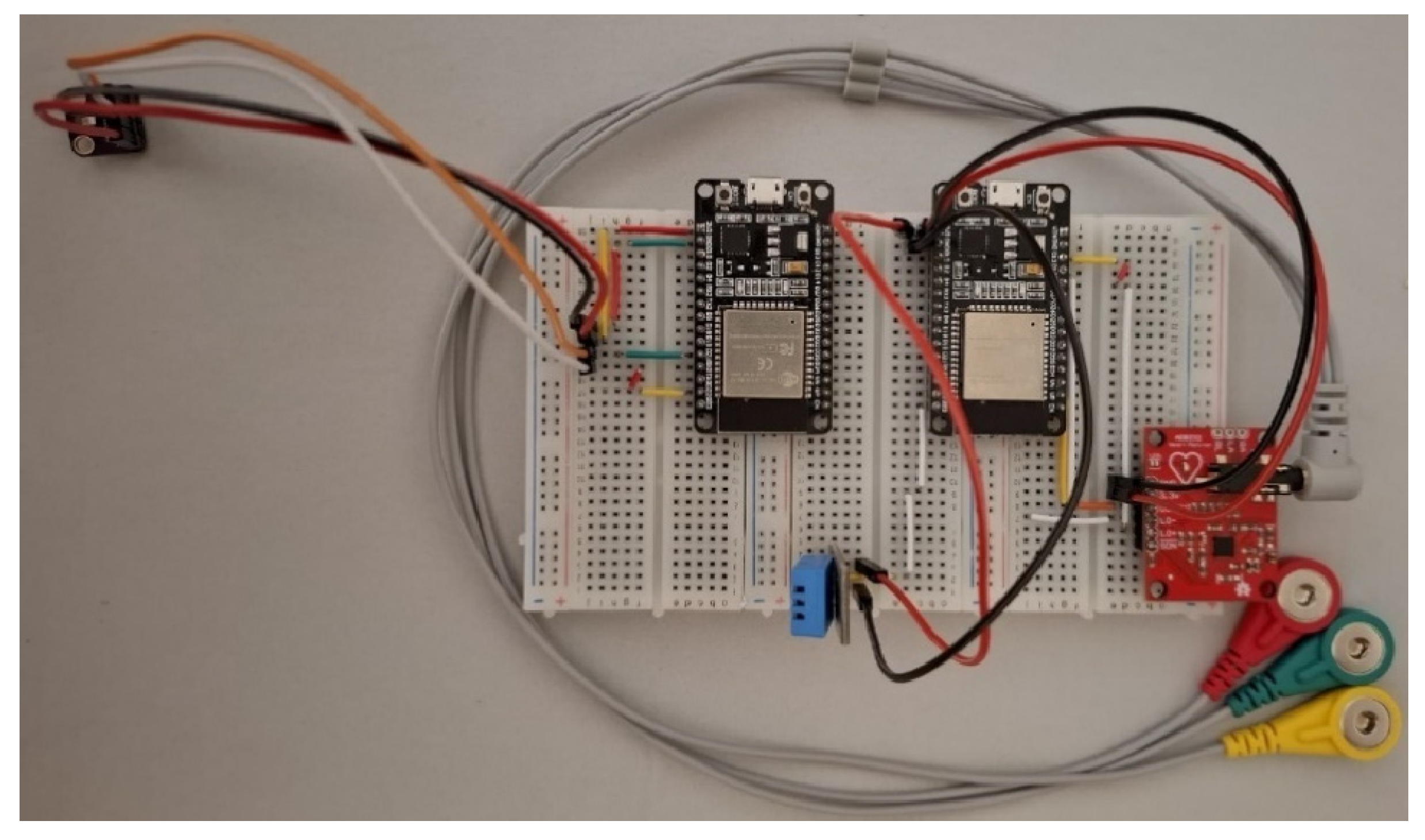

The assembled hardware implementation is shown in

Figure 4, corresponding to the prototype used in validation.

2.3. Software Implementation

The system firmware was developed using MicroPython v1.20.0 (MicroPython Foundation, Cambridge, UK) and deployed through the Thonny IDE v4.1.2 (University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia). The data-publishing process was managed through a Python-based interface implemented in the Spyder IDE v5.5.1 (Spyder Project/Quansight, Austin, TX, USA), which serializes and transmits selected FHIR files via MQTT to the ESP32 node. Upon receiving the message, the microcontroller decodes the JSON payload, extracts the signal parameters, and repackages the processed data for transmission to the Home Assistant server.

The ESP32 node runs MicroPython firmware supporting wireless connectivity and local JSON parsing, while the middleware stack—comprising Mosquitto, Home Assistant, InfluxDB, and Grafana—handles message routing, persistence, and visualization. The containerized setup in VMware (VMware Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA) ensures reproducibility and isolation during experimental validation.

2.4. Data Security and Interoperability

To ensure compliance with healthcare data protection requirements, several security mechanisms were implemented: TLS encryption for all MQTT transactions; token-based authentication between clients and the broker; and local data storage on the InfluxDB server, minimizing external dependencies and ensuring GDPR compliance.

In this implementation, heart rate was encoded using LOINC 8867-4, oxygen saturation using LOINC 59408-5, and temperature using LOINC 8310-5. UCUM units ‘%’, ‘degC’, and ‘ms’ were used accordingly. These standardized codes ensure semantic interoperability with FHIR-compliant clinical systems.

Physiological measurements were transmitted as individual FHIR Observations at each acquisition cycle; session-level Bundles were not generated in this prototype.

TLS 1.2 encryption and SHA-256-based authentication were configured within the Mosquitto broker, ensuring the confidentiality and integrity of all transmitted payloads.

Furthermore, interoperability across hardware and software layers was validated by maintaining the HL7 FHIR format end-to-end—from data generation at the acquisition layer to visualization in Grafana—demonstrating that each component correctly preserved data integrity, metadata, and temporal synchronization.

The validation also confirmed that HL7-compliant JSON structures remained semantically intact after decoding, storage, and retrieval, ensuring full compliance with the standard throughout the data path.

Additional security considerations are required to address the needs of biomedical IoMT deployments fully. In accordance with best practices, the system shall explicitly define its threat model, including potential adversarial actions such as eavesdropping, message tampering, credential replay, and broker impersonation.

Furthermore, MQTT topic-level Access Control Lists (ACLs), TLS cipher suite specifications, secure key provisioning methods, and certificate lifecycle management (issuance, rotation, and revocation) should be formally documented. Mutual authentication mechanisms and device-attestation strategies are recommended for clinical-grade environments.

A hybrid validation and security model for MQTT-based biomedical telemetry—emphasizing device attestation, certificate rotation, and threat-mitigation strategies—has been presented in [

20]. This framework provides a relevant conceptual basis for improving certificate lifecycle management and secure onboarding within clinical IoMT deployments.

These additions align the proposed architecture with contemporary cybersecurity models in medical informatics, such as the hybrid validation framework, and strengthen the system’s suitability for healthcare applications.

In this prototype, MQTT communication used TLS 1.2 with username/password authentication, but did not implement mutual TLS or device attestation. Topic-level ACLs were configured on the Mosquitto broker to restrict publish/subscribe privileges. No identifiable patient data were transmitted, and all subjects were represented using anonymised dummy identifiers.

A minimal security-hardening checklist, including TLS enforcement, credential rotation, pseudonymisation rules, and broker-level ACL configuration, is provided in the

Supplementary Materials. Secure key provisioning and device-attestation mechanisms were not implemented in this prototype and remain subjects for future extensions toward clinical-grade deployments [

33].

2.5. Validation Environment and Configuration

The validation process was conducted in a controlled environment simulating a real-time patient-monitoring scenario. An HL7 FHIR “Observation” file containing three-lead ECG data was selected as the test input. The system was deployed on a VMware virtual machine running Home Assistant, InfluxDB, and Grafana.

Wireless communication between the acquisition node and the virtual server was established via a local Wi-Fi network, with latency and data loss monitored across multiple transfer cycles. The experiment confirmed stable communication and real-time visualization of the ECG waveform with minimal delay.

To support reproducibility, key configuration snippets and MQTT connection parameters are summarized in the

Supplementary Materials. Validation metrics—including end-to-end latency, sampling-rate stability, and packet loss—were monitored across ten acquisition sessions, as detailed in

Section 3.4.

The detailed implementation of the acquisition hardware, firmware structure, and experimental validation is presented in

Section 3.

A public repository will be released in a future version; at this stage, only the firmware structure and configuration parameters are provided to maintain prototype-level reproducibility.

3. Case Study: Implementation and Validation

3.1. Experimental Setup

The experimental validation was performed on a multi-sensor module for vital-sign monitoring centered on the ESP32-WROOM-32 development board, which managed HL7 FHIR message assembly, reception, decoding, and wireless transmission. The sensing front-end integrated four biomedical transducers: AD8232 for electrocardiogram (ECG) signal acquisition, GY-MAX30102 optical biosensor (Analog Devices/Maxim Integrated, San Jose, CA, USA) for photoplethysmography (PPG), heart rate (HR), and oxygen saturation (SpO

2), and DHT11 temperature–humidity sensor (Aosong Electronics, Guangzhou, China) for body temperature and humidity measurement. Similar ESP32-centered biomedical acquisition systems have been reported in low-cost sensing studies [

34].

The DHT11 module was included as a low-cost demonstrator of the acquisition pipeline [

21]. ECG acquisition was performed using the AD8232 analog front-end optimized for biopotential measurements [

23]. Photoplethysmographic signals, heart rate, and SpO

2 were obtained using the GY-MAX30102 optical biosensing module [

24]. Given that no certified clinical thermometer was available during the experiments, a formal Bland–Altman agreement analysis could not be performed within this prototype. Consequently, the present work focuses on demonstrating the acquisition and interoperability aspects of the temperature channel rather than its clinical accuracy.

The hardware configuration of the experimental setup is summarized in

Table 1, while

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 present the electronic schematic created in Fritzing and the corresponding assembled prototype.

The physical implementation of the acquisition module is illustrated in

Figure 4, showing both the wiring diagram and the assembled hardware prototype. The system architecture ensures proper isolation between analog and digital circuits, minimizing interference and providing stable signal conditioning for biomedical measurements.

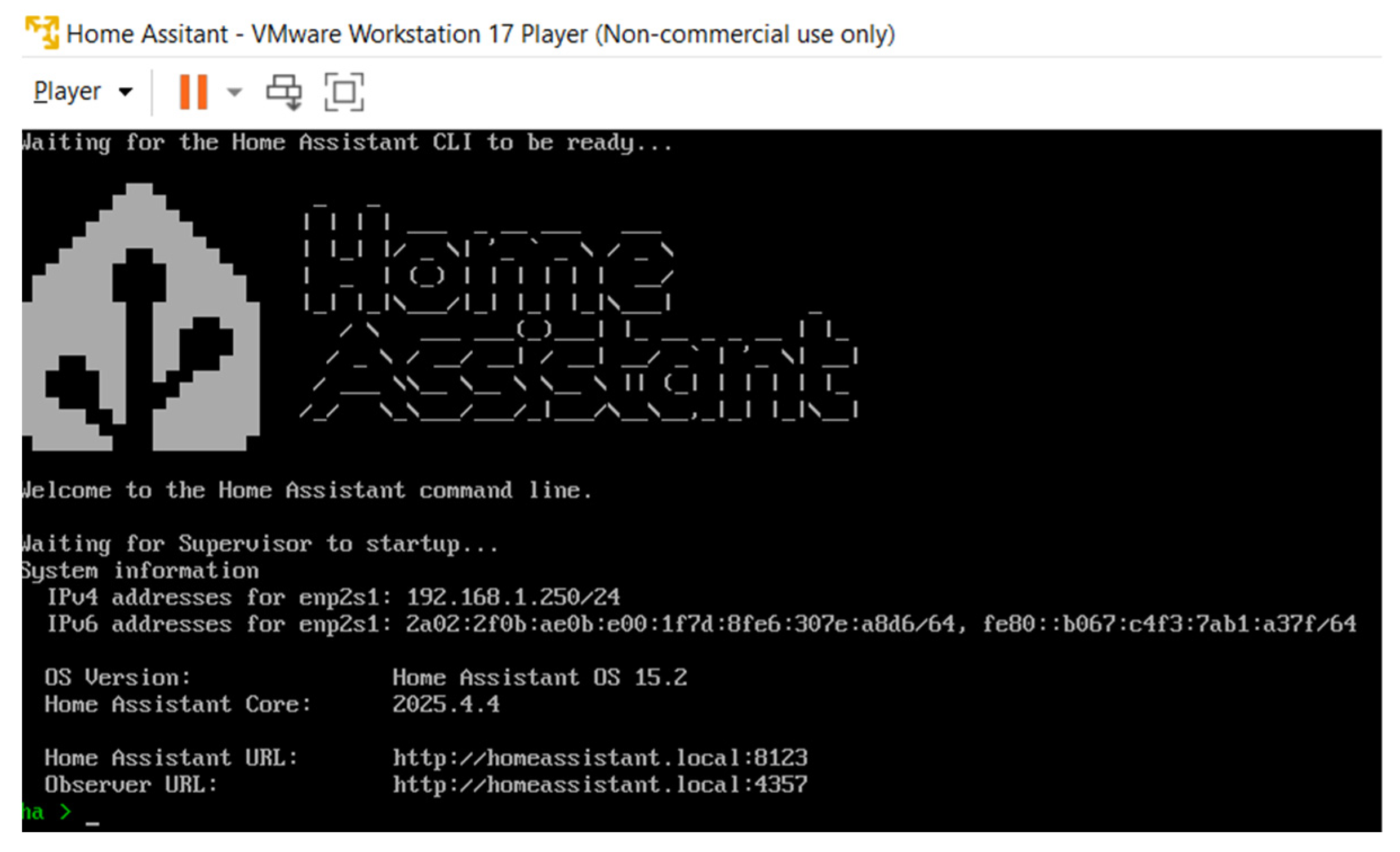

The integration platform was executed locally on a VMware Workstation 17 Player instance running Ubuntu 22.04 LTS (Canonical Ltd., London, UK), hosting Home Assistant as the middleware layer with Mosquitto (MQTT broker), InfluxDB (time-series database), and Grafana (data visualization tool). All modules communicate within a local Wi-Fi network, ensuring sub-second transmission latency and complete control over data flow. The integration platform was hosted locally on VMware, as illustrated in

Figure 5.

The ECG signals were acquired using medical-grade Ag/AgCl disposable electrodes with solid hydrogel, connected via a shielded 3.5 mm TRS cable to the AD8232 amplifier. The technical characteristics of the electrodes are provided in

Table 2. To minimize interference, the acquisition laptop remained disconnected from the AC power supply during all tests.

All sensors and modules were calibrated for synchronized operation, ensuring consistent sampling across all acquisition channels. The HL7 FHIR file structure implemented in the firmware maintained timestamped entries for each signal, enabling complete interoperability testing across the hardware, MQTT transport, and visualization layers.

3.2. HL7 FHIR Observation Structure and Data Flow

The developed system employs a unified HL7 FHIR Observation resource to represent all acquired physiological parameters in a structured and semantically interoperable format. Continuous biosignals—such as electrocardiographic (ECG), photoplethysmographic (PPG), and temperature time-series—were encoded using the valueSampledData element, which stores numerical sequences together with their metadata: origin, scaling factor, sampling period, and physical units [

31]. Similar FHIR-based waveform-encoding workflows have been demonstrated in recent biomedical informatics studies [

35,

36], confirming the feasibility of integrating IEEE 11073 metadata with HL7 FHIR for multi-sensor physiological time-series.

Scalar physiological quantities, such as blood oxygen saturation (SpO2) and heart rate (BPM), were represented by the valueQuantity structure, allowing each Observation to encapsulate both waveform and scalar components in a consistent schema. This dual representation ensures compatibility with standard-compliant medical record systems and enables automatic data parsing across heterogeneous platforms.

Each Observation instance includes mandatory metadata fields—identifier, device reference, acquisition timestamp, and component list—ensuring traceability from the sensor level to the visualization layer. The hierarchical structure of the message maintains semantic integrity across all transmission stages, supporting real-time clinical interpretation and subsequent integration into electronic health record (EHR) systems.

The data generation and integration flow—from multi-sensor capture, local formatting into HL7 FHIR JSON, MQTT publication, to real-time visualization in Grafana—is illustrated in

Figure 6.

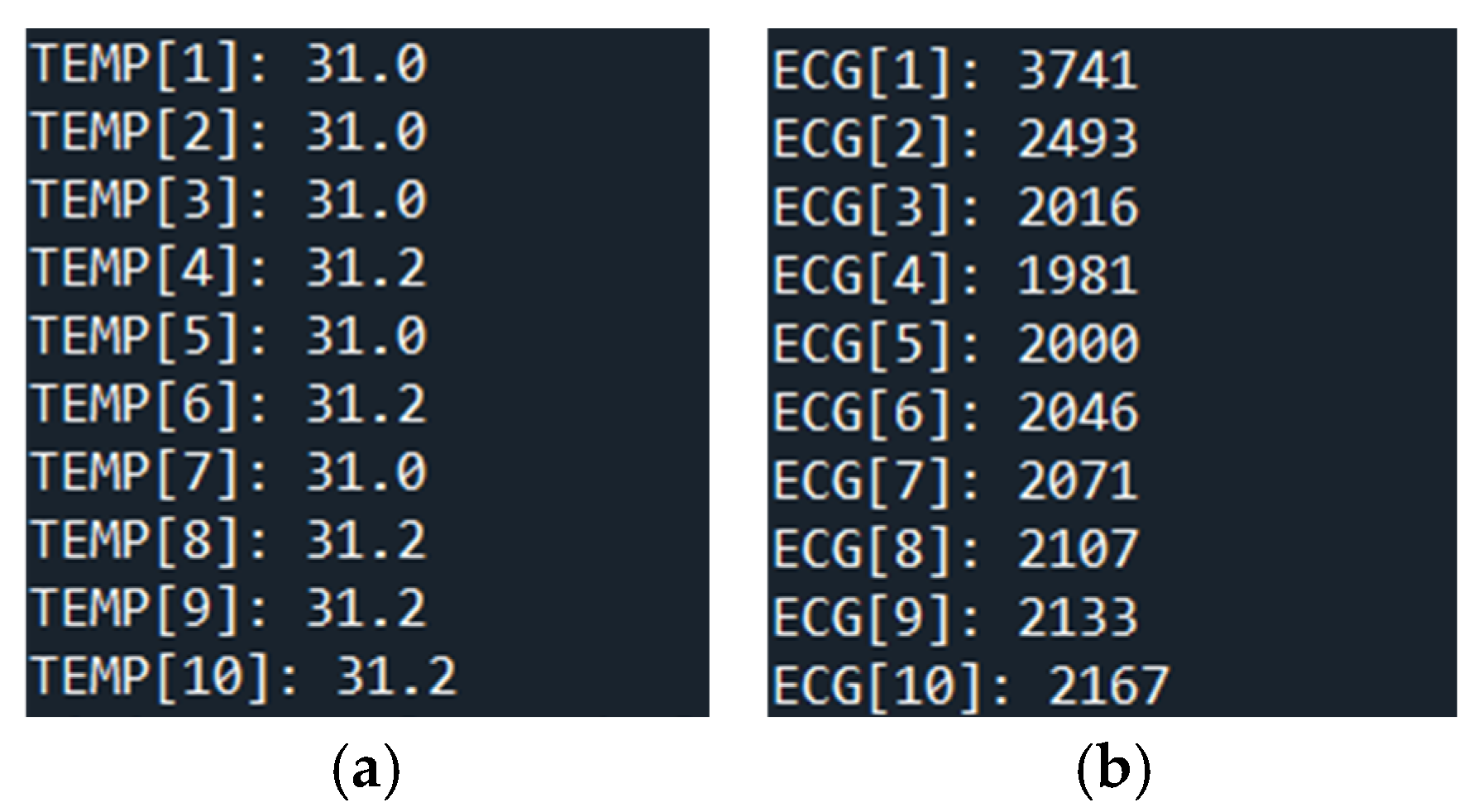

Representative HL7 FHIR Observation components are shown in

Figure 7, illustrating temperature (10 samples) and ECG SampledData encoding (300 samples) within the valueSampledData structure. These examples confirm the correct encoding of time-series data with explicit temporal metadata and the use of valueQuantity for scalar indicators, validating full compliance with HL7 FHIR standards.

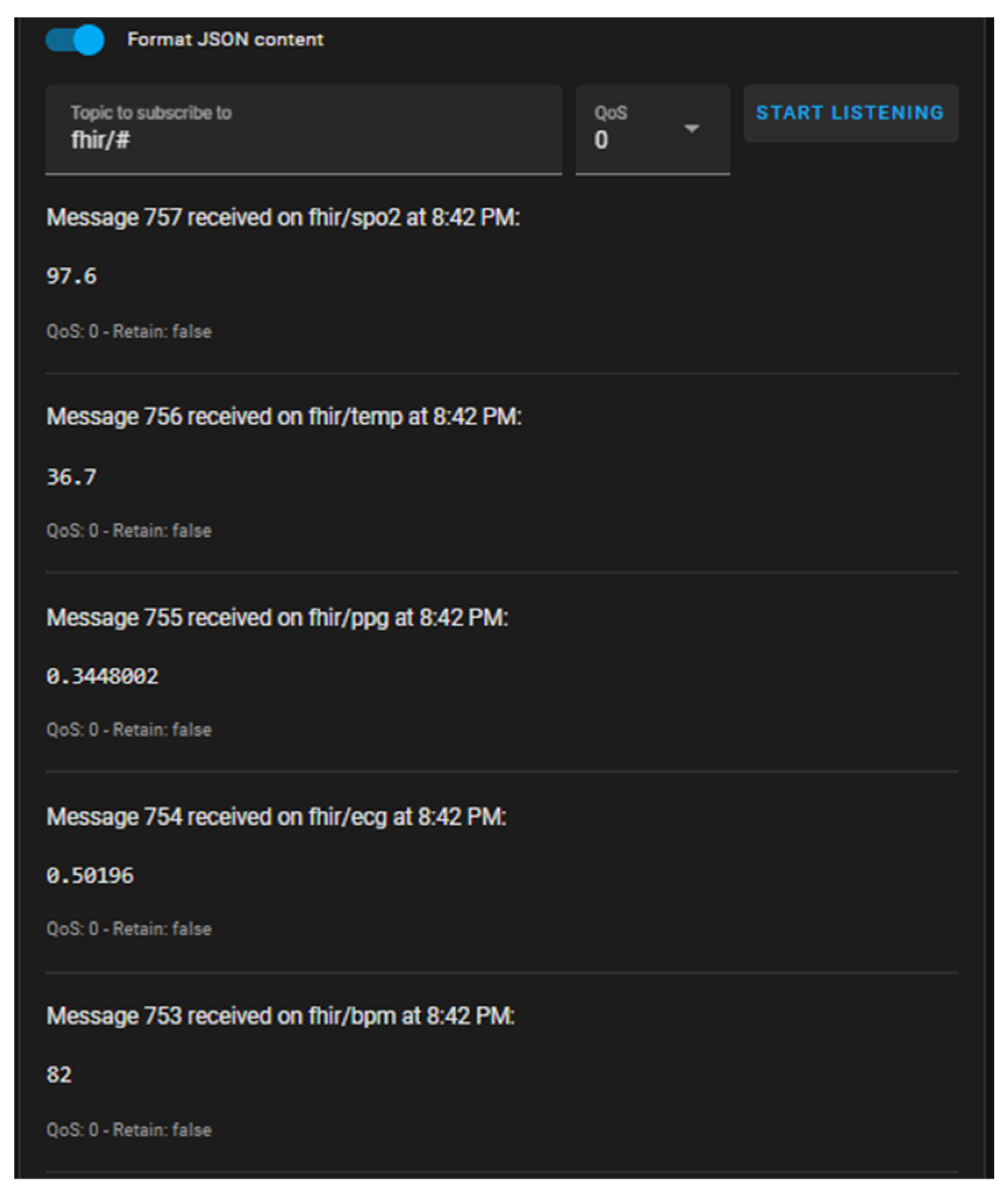

The ECG sequence corresponds to a 3-s window, while temperature values are represented as scalar entries within the same Observation structure. During experimental runs, the ESP32 nodes performed synchronized sampling (ECG at 100 Hz; temperature at 0.5 Hz; optical PPG buffers over 300 samples per cycle) and published their outputs to dedicated MQTT topics—waveform data (ECG/PPG) under fhir/ecg and fhir/ppg, and scalar values (SpO2, BPM, temperature) under fhir/spo2, fhir/bpm, and fhir/temp. The uniform timestamp alignment maintained within the generated HL7 messages ensured accurate correlation between physiological parameters and reproducible cross-channel analysis.

3.3. Integration in the Open-Source Platform

Following deployment of the acquisition module, the ESP32 nodes communicated wirelessly through the Mosquitto MQTT broker, enabling bidirectional data exchange between the hardware layer and the integration platform. Upon startup, each node published HL7 FHIR Observation payloads under predefined topics and simultaneously subscribed to control channels for configuration or synchronization commands. The topic hierarchy—structured as fhir/ecg, fhir/ppg, fhir/spo2, fhir/bpm, and fhir/temp—allowed selective message routing and modular scalability across multiple nodes.

The Home Assistant environment served as middleware, automatically registering each MQTT topic as a virtual sensor entity. Sensor metadata, units, and data types were defined within the configuration.YAML file, ensuring persistent identification of all channels. The broker configuration was secured using TLS 1.2 encryption and SHA-256-based authentication, providing confidentiality and message integrity during transmission.

At the data management layer, InfluxDB was employed as a time-series database optimized for biomedical telemetry. The decoded physiological values received via MQTT were continuously written to dedicated measurement tables. InfluxDB’s high-resolution timestamping (sub-millisecond precision) ensured accurate temporal alignment across ECG, PPG, and scalar channels, facilitating subsequent correlation and analysis.

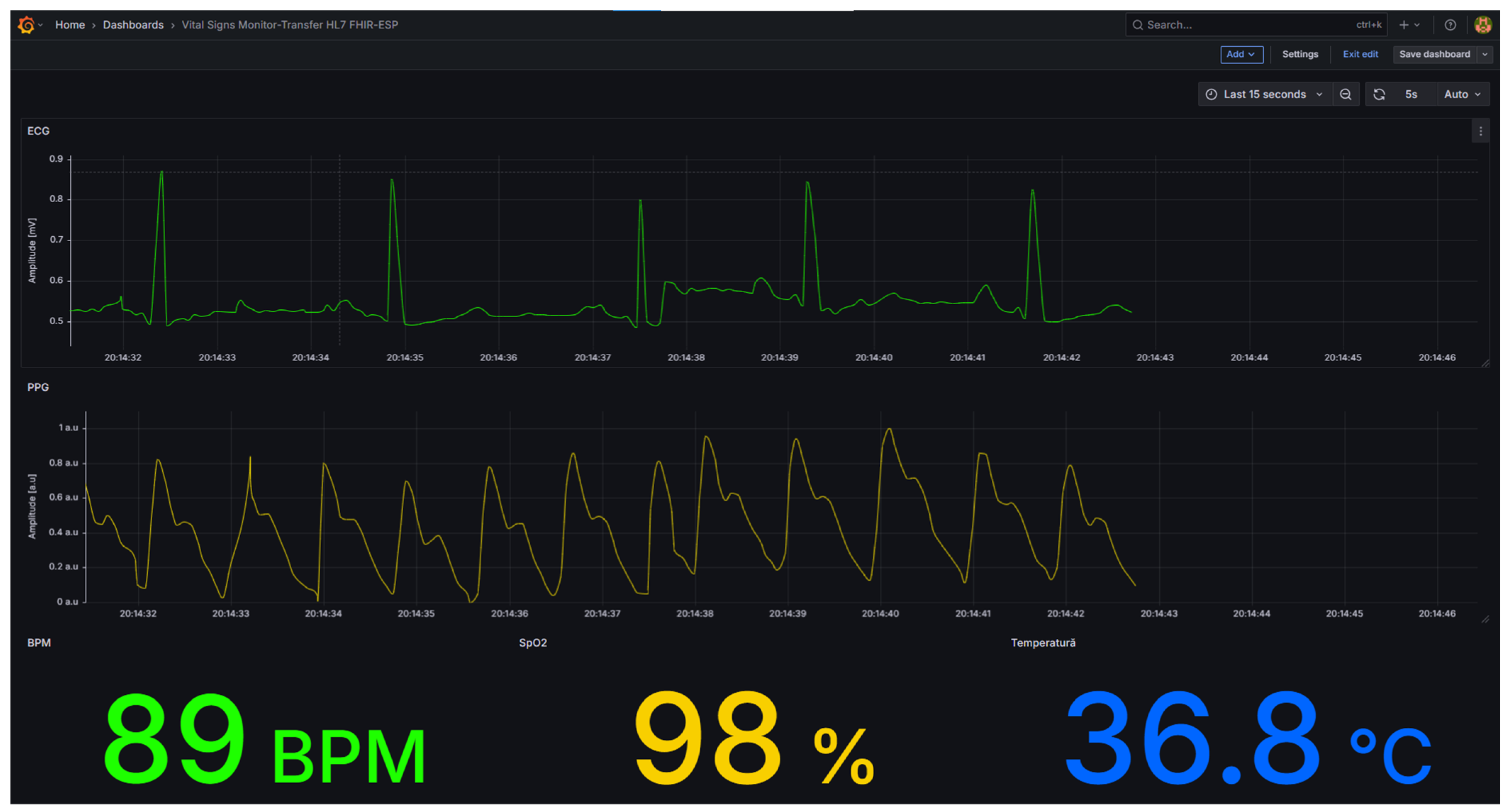

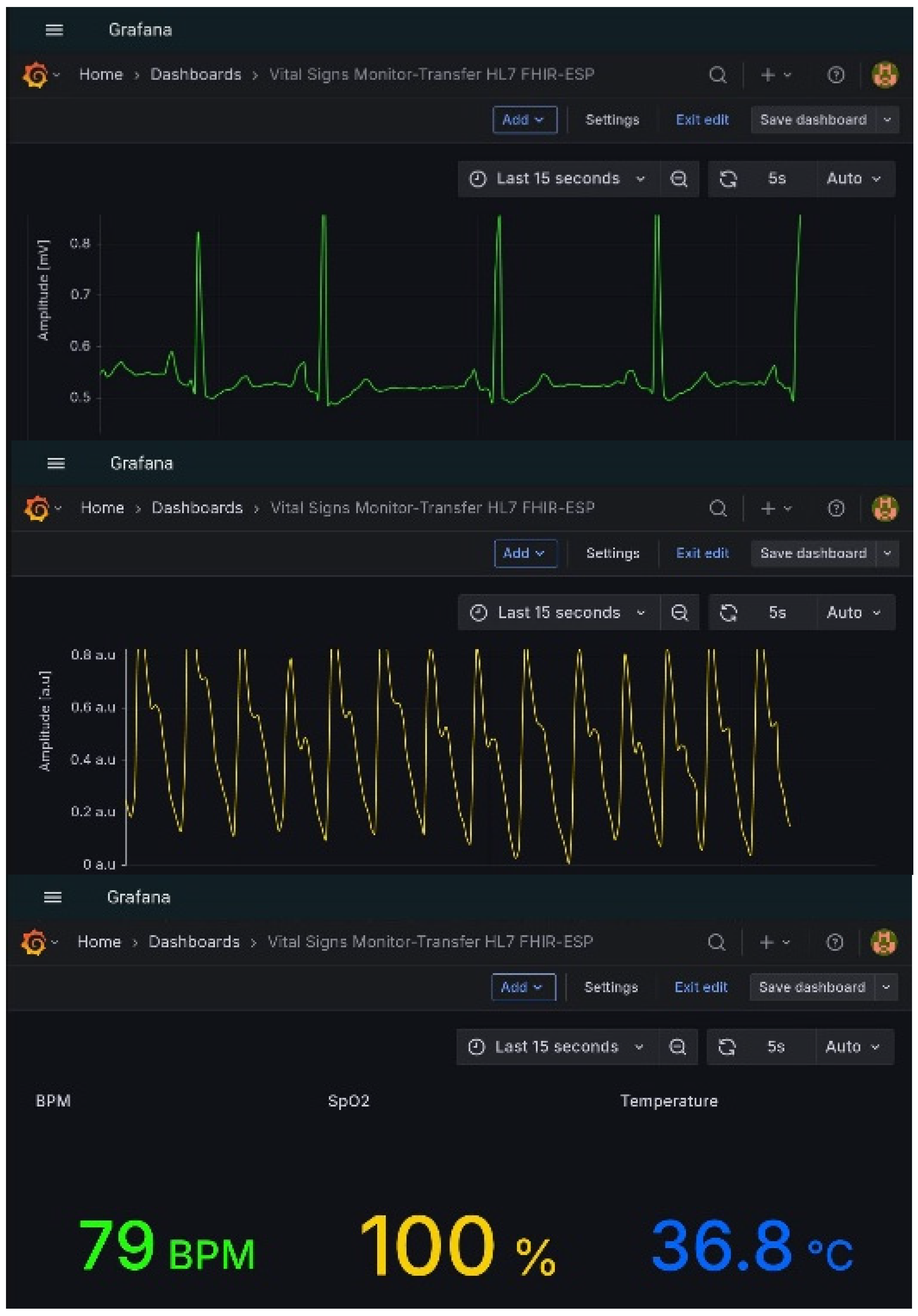

Visualization and human–machine interaction were handled through Grafana, which accessed the InfluxDB database via an HTTP API connection. Multiple dashboards were designed to display both waveform and scalar data. Time-varying graphs were configured for ECG and PPG signals, while numeric panels displayed instantaneous physiological parameters, including body temperature, heart rate, and oxygen saturation.

Incoming physiological parameters at the MQTT broker are displayed in

Figure 8, where physiological parameters are published under their respective MQTT topics of the fhir/# type. Grafana dashboards offering real-time visualization of waveform and scalar parameters are shown in

Figure 9.

A preliminary visual inspection of the acquired ECG and PPG waveforms indicated stable morphology and acceptable baseline drift. The broader signal-quality assessment—limited to indicative considerations regarding signal-to-noise characteristics and qualitative comparison with clinically reported ranges—is presented methodologically rather than numerically, as no certified comparators were available during acquisition. These methodological aspects and their limitations are discussed conceptually in this subsection.

To extend portability and field accessibility, the same Home Assistant–Grafana environment was deployed on mobile devices (Android) using the Home Assistant Companion application. This configuration enabled clinicians to monitor physiological data streams in real time from any location within the secure network domain, whether local or remote. Mobile visualization through the Home Assistant Companion application is illustrated in

Figure 10.

From an architectural standpoint, the integration demonstrates that a fully open-source stack—comprising MQTT transport, Home Assistant orchestration, InfluxDB storage, and Grafana visualization—can sustain continuous biomedical data acquisition with sub-second end-to-end latency. The system preserves semantic interoperability because all parameters are encoded in the HL7 FHIR Observation format throughout the pipeline. Furthermore, local hosting within VMware minimizes dependency on external clouds and ensures complete data sovereignty and GDPR compliance.

The complete communication and visualization workflow validated the feasibility of interoperable IoMT infrastructures for medical research, teaching laboratories, and clinical prototyping. The quantitative results of this validation are detailed in

Section 3.4 (Validation Results).

3.4. Validation Results

The validation campaign was conducted to evaluate the reliability, latency, and semantic integrity of the complete acquisition and data integration chain—from biosignal capture at the ESP32 nodes to visualization in Grafana. Each session included simultaneous acquisition from both nodes under stable network conditions (Wi-Fi 2.4 GHz, nominal throughput 150 Mbps), with all components synchronized to a standard Network Time Protocol (NTP) source.

The unified HL7 FHIR Observation was generated in two successive stages to reflect the dual-node configuration: (i) the first ESP32 node contributed temperature (10 samples) and ECG (300 samples), while (ii) the second node appended PPG (300 samples), SpO2 (10 readings), and BPM (10 readings).

Representative excerpts of the resulting Observation and the corresponding channel segments were previously shown in

Figure 7, confirming proper hierarchical encoding via the valueSampledData and valueQuantity structures.

Timestamps were instrumented at four conceptual measurement points in the acquisition chain—(i) at the ESP32 publisher, (ii) upon broker reception, (iii) at InfluxDB write completion, and (iv) at data ingestion by Grafana—to define the methodological basis for latency estimation. The reported end-to-end latency excludes visualization-rendering time.

Visualization-rendering time in Grafana was explicitly excluded from all latency estimates. Because the ESP32 nodes lacked timestamp-level hardware logging and the dataset was limited, no statistically meaningful confidence interval estimation or latency distribution analysis could be performed in this prototype. The methodological framework and associated limitations are discussed conceptually in this subsection.

3.4.1. Qualitative Validation

End-to-end tests verified the system’s ability to maintain the semantic consistency of HL7 FHIR JSON payloads across all transmission layers. The following criteria were used for qualitative validation:

Integrity check—No structural deviation of FHIR components was observed after multiple serialization/deserialization cycles.

Temporal alignment—All waveform channels (ECG, PPG, temperature) remained synchronized within ±5 ms across dual nodes.

Visualization consistency—The same numerical values recorded in InfluxDB were accurately rendered in Grafana panels, confirming the fidelity of the end-to-end pipeline.

No packet loss was detected in any of the ten repeated test runs. The observed delay from publication to visualization remained below one second, consistent with bedside monitoring requirements for telemetry-grade IoMT systems.

Both ESP32 nodes were synchronized to a local NTP server (chrony on Ubuntu 22.04, update interval 60 s), which maintained a drift of approximately ±5 ms over 60 s windows.

3.4.2. Quantitative Performance Analysis

To complement the qualitative findings, a quantitative performance assessment was conducted across 10 consecutive acquisition cycles (60 s each). Key parameters—latency, packet loss, ECG sampling rate, per-message throughput, and CPU utilization—were recorded and averaged.

The results, summarized in

Table 3, confirm near real-time responsiveness and demonstrate that the system can operate continuously without degradation or data loss.

The results show that message throughput and CPU utilization remain well within the ESP32 microcontroller’s operational envelope, with sufficient processing margin for additional sensors or data-processing tasks. The consistent ECG sampling rate confirms the timing precision of the valueSampledData structure and validates that the HL7 FHIR format introduces negligible overhead in real-time transmission scenarios.

A complete multi-node scalability assessment under variable network contention is left for future work and is discussed in

Section 4.3.

3.4.3. End-to-End System Visualization

Figure 11 offers an integrated overview of the complete data path, combining the acquisition and HL7 FHIR encoding workflow (

Figure 6) with the local open-source platform architecture (

Figure 5).

The architecture demonstrates seamless interoperability among all layers: ESP32 nodes for signal acquisition, Mosquitto for MQTT transport, Home Assistant for message orchestration, InfluxDB for time-series storage, and Grafana for real-time visualization.

Data from the ESP32 nodes are encoded into HL7 FHIR Observation messages, published via the MQTT broker (Mosquitto), and processed by Home Assistant integrated with InfluxDB and Grafana. The platform operates locally within a VMware instance to minimize latency and ensure complete control over data privacy and access.

3.4.4. Summary of Validation Findings

The experimental validation confirmed that:

The system ensures complete semantic consistency of physiological data across all layers of the architecture through the standardized HL7 FHIR format.

End-to-end latency is sub-second, suitable for clinical and educational telemonitoring contexts;

Packet loss is effectively null, even under continuous streaming conditions;

Computational load remains below 50%, enabling scalability to additional biomedical modalities.

These findings demonstrate that the proposed configuration can serve as a benchmark architecture for reproducible, open-source implementations of biomedical Internet of Things (IoMT) systems adhering to FAIR data principles.

4. Discussion

The validation results confirm that the proposed open-source architecture—comprising ESP32-based acquisition nodes, an MQTT transport layer, and a Home Assistant–InfluxDB–Grafana integration stack—achieves real-time, interoperable, and secure biomedical data exchange using the HL7 FHIR standard.

The overall data flow, summarized in

Figure 11, illustrates the interoperability of all layers, from sensor-level acquisition and HL7 encoding to storage and visualization. Each message retains its semantic structure and metadata throughout the entire transmission pipeline, ensuring data integrity and traceability—a key requirement in medical telemetry and clinical informatics [

11,

12,

15,

16,

25,

30,

37].

In contrast to proprietary middleware or vendor-locked cloud gateways, the proposed framework demonstrates that fully open-source implementations can achieve comparable performance while providing significantly greater transparency. This is particularly relevant for healthcare research environments, where reproducibility, auditability, and compliance with data-protection regulations are essential. The observed end-to-end latency below 1s and zero packet loss confirm that the system meets the responsiveness criteria for bedside or continuous patient monitoring.

From a systems engineering perspective, three technical aspects stand out:

Semantic interoperability through HL7 FHIR. The dual use of valueSampledData for waveform signals and valueQuantity for scalar indicators provides a flexible yet compact encoding scheme. This structure eliminates the need for custom parsers while preserving machine-readability and self-description of physiological data, facilitating downstream analytics and cross-platform data fusion.

Localized data orchestration and security. Hosting all services within a VMware-based environment ensures independence from external cloud infrastructures, minimizing cybersecurity and privacy risks. The combination of TLS 1.2 encryption, SHA-256 authentication, and local database storage enables compliance with GDPR and ISO/IEC 27001 [

38] principles for medical data protection.

Scalability and modularity. The MQTT topic hierarchy (fhir/#) allows seamless addition of new biosignal nodes or measurement modalities (e.g., respiration rate, non-invasive blood pressure) without modifying the existing system architecture. The average CPU load below 50% further indicates sufficient computational headroom for embedded preprocessing or adaptive filtering directly on the ESP32 nodes.

4.1. Implications for Deployment

The architecture aligns with the emerging paradigm of edge–cloud medical computing, where preliminary filtering, feature extraction, or data quality evaluation occur near the sensors before transmission to centralized hospital middleware or research repositories. Such hybrid configurations enable distributed decision-support systems that combine near-real-time monitoring with long-term clinical analytics. The proposed stack can thus be deployed in applications including:

remote patient monitoring in telemedicine or home-care settings,

rapid prototyping of decision-support tools for teaching laboratories,

experimental platforms for EHR integration using HL7 FHIR RESTful APIs.

Exclusively relying on open-source components promotes reproducibility and transparency, facilitating independent validation of the architecture and its adaptation to a variety of biomedical contexts.

4.2. Limitations

While the results validate the interoperability and latency performance, certain limitations must be acknowledged. Experiments were performed in a controlled environment, free of motion artifacts and external electromagnetic interference. Real-world hospital deployments may introduce additional variability due to Wi-Fi congestion, sensor detachment, or ambient noise.

Furthermore, although the security model was robust at the transport layer (TLS 1.2), it lacked certificate lifecycle management, device attestation, and mutual authentication, which are critical in clinical environments. Finally, the quantitative assessment focused on latency and packet loss, while other metrics such as temporal jitter, timestamp drift, and end-to-end synchronization errors remain subjects for future investigation.

4.3. Future Work

Future research directions include:

Clinical-grade validation involving human participants and certified reference devices to assess medical accuracy under diverse physiological conditions.

Multi-node scalability studies under variable network load and interference, to evaluate performance in high-density IoMT deployments.

Integration of embedded intelligence at the edge—using on-board anomaly detection or adaptive data quality assessment—before HL7 message generation.

EHR and cloud interoperability testing via HL7 FHIR REST APIs, to demonstrate automated order/result exchange and inter-institutional data portability.

The open-source architecture of the implementation supports reproducibility and reusability by other researchers, in line with the FAIR data principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) promoted in modern digital medicine.

Although multi-node evaluation was not performed experimentally, a throughput analysis indicates that Mosquitto can sustain ≥300 messages/s under QoS0 on a 2.4 GHz Wi-Fi LAN, and InfluxDB can handle >10k writes/min. With 5–10 ESP32 nodes sampling at the tested rates, CPU and broker load remain well within system limits.

4.4. Summary of Contributions

The study demonstrates that open-hardware platforms (e.g., ESP32), combined with standardized interoperability frameworks (e.g., HL7 FHIR) and open-source software layers—including Mosquitto MQTT v2.0.15 (Eclipse Foundation, Ottawa, ON, Canada), Home Assistant v2024.6 (Nabu Casa, San Diego, CA, USA), InfluxDB v2.7 (InfluxData, San Francisco, CA, USA), and Grafana v10.2 (Grafana Labs, New York, NY, USA)—can achieve medical-grade data acquisition with low latency, full semantic traceability, and compliance with data-protection requirements.

5. Conclusions

This work presented the design, implementation, and validation of a fully open-source framework for biomedical signal acquisition and interoperable data integration based on the HL7 FHIR standard. The system—built around ESP32-WROOM-32 sensing nodes, MQTT communication, and an open-source Home Assistant–InfluxDB–Grafana platform—achieved reliable, real-time, and secure exchange of physiological data encoded in FHIR Observations.

The case study conducted on a multi-sensor vital-sign monitoring module was selected as a representative and reproducible experimental configuration. It provides a concrete validation scenario in which heterogeneous biosignals (ECG, PPG, temperature, SpO2, and heart rate) are acquired, encoded, transmitted, and visualized through a standardized, end-to-end pipeline. This choice was justified by its high relevance to clinical monitoring contexts and its ability to test the complete interoperability chain—from edge acquisition to human–machine visualization—under realistic operational constraints. The successful integration of this setup demonstrates the feasibility of implementing semantically interoperable IoMT systems using only open-source components and non-proprietary middleware, thus ensuring transparency, reproducibility, and accessibility for research and education.

Experimental validation confirmed semantic integrity, zero packet loss, and sub-second latency, satisfying the performance requirements for bedside and telemedicine monitoring. Quantitative measurements also showed sufficient processing headroom for additional biosensors and edge-level signal processing, both of which are crucial for scalable healthcare deployments.

From an engineering standpoint, the presented architecture bridges the gap between academic IoMT prototypes and clinically applicable, interoperable infrastructures, providing a reference implementation that can be extended toward hospital-grade environments or embedded clinical research networks.

Overall, this study contributes to advancing FAIR-aligned, open, and interoperable digital health ecosystems, reinforcing the role of standardized HL7 FHIR data structures in developing transparent, secure, and reusable biomedical information systems.