1. Introduction

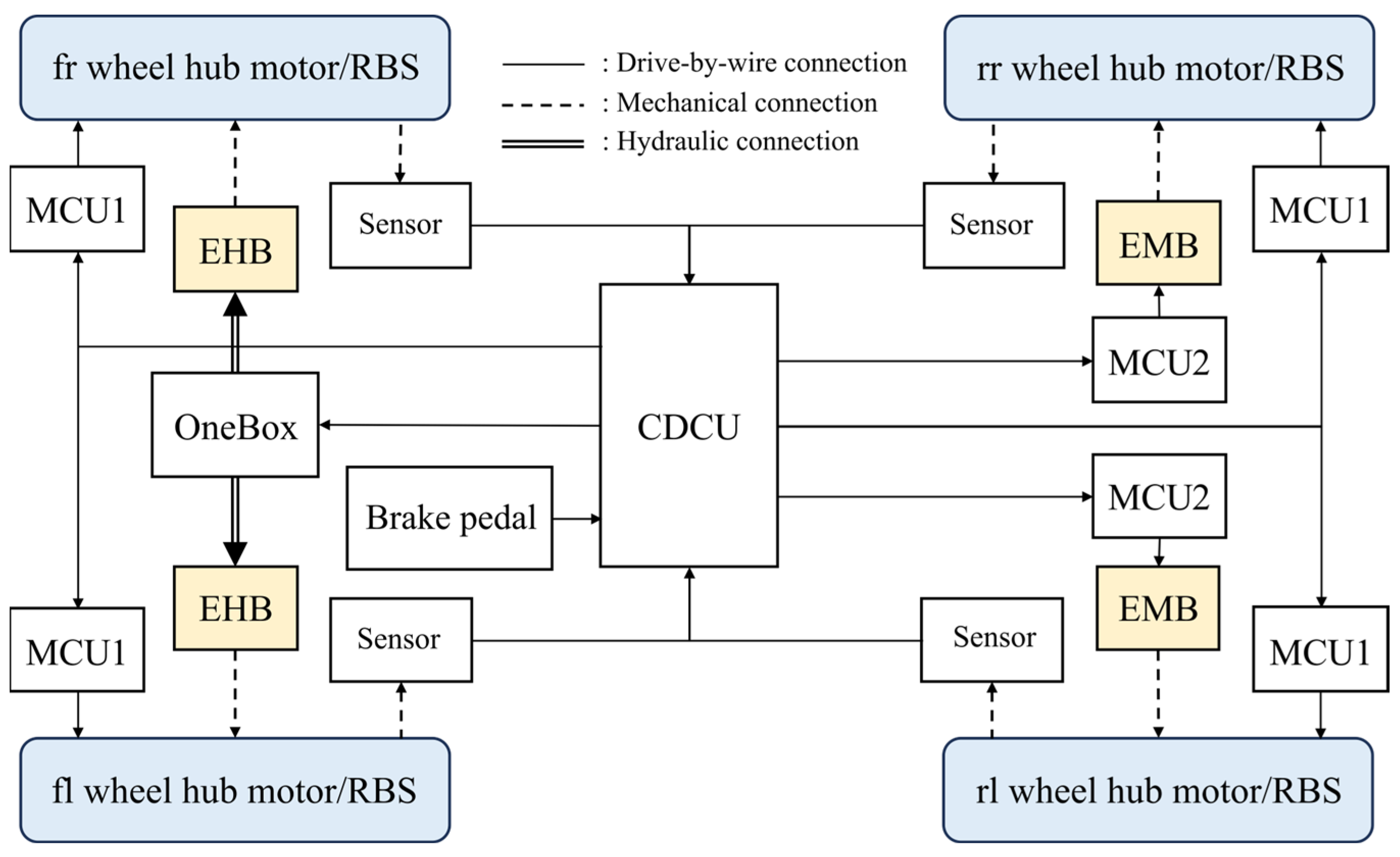

With the increasing popularity of automobiles, environmental pollution poses severe challenges to improving the fuel economy of internal combustion engine vehicles. As an alternative solution, electric vehicles (EVs) attract significant attention for their potential to alleviate environmental pollution and energy shortages [

1]. Meanwhile, vehicle chassis systems are evolving from the mechanically actuated configurations of conventional vehicles toward brake-by-wire, steer-by-wire, and suspension-by-wire systems in EVs. The brake-by-wire system addresses the issue of high coupling of braking forces among wheels in traditional braking systems, thereby enhancing the flexibility and freedom of braking force distribution. However, this also presents new challenges for braking force coordination. Traditional braking force distribution control utilizes a decentralized architecture, wherein subsystems such as electronic brakeforce distribution (EBD), anti-lock braking system (ABS), and direct yaw-moment control (DYC) collect vehicle data through their respective sensors and issue commands to the brake actuators based on their own control objectives [

2]. Although this decentralized architecture offers a high degree of in-dependence among subsystems, it does not meet the requirements of the brake-by-wire system for flexible braking force coordination. Additionally, conflicts among subsystem commands can arise, reducing braking effectiveness. Consequently, a coordinated braking force control strategy is necessary to improve braking safety in EVs. On distributed drive platforms with four in-wheel motors, each drive motor, under the control of the regenerative brake system (RBS), can generate independent electric braking force at its corresponding wheel. This produced electric braking force is redundant with the mechanical braking force generated by the mechanical brake actuators, presenting new opportunities for coordinated braking force control. However, as the complexity of brake-by-wire systems in-creases, the likelihood of failures also grows, making it increasingly urgent to investigate braking force distribution and coordination strategies that can address braking force failure.

Braking force coordination control needs to reconcile the different requirements of sub-systems such as ABS, EBD, and DYC for braking force distribution, while also considering coordination strategies under brake system failure conditions. Tang et al. [

3] proposed an MPC-based RBS-ABS coordination control strategy employing a nonlinear three-degree-of-freedom predictive model to compute the required braking torque corresponding to the desired wheel slip ratio. Xu et al. [

4] designed a coordination control method for RBS and ABS in hybrid electric vehicles with compound motor structures. Liang et al. [

5] proposed a coordination controller based on functional allocation, where the upper layer designs a dynamic stability envelope boundary using the phase plane method, the mid-layer employs robust

feedback control and an improved PSO algorithm to calculate the additional yaw moment required by DYC, and the lower layer utilizes the Sequential Quadratic Programming (SQP) algorithm to coordinate wheel torque and braking torque. Zheng et al. [

6] developed an extensible hierarchical coordination controller that considers the bounded rationality of control systems, where the monitoring layer uses an extension phase-plane method to classify vehicle states, and the coordination decision layer treats active front-wheel steering and DYC control as game-theoretic agents. Anh et al. [

7] proposed compensating for the delay of hydraulic braking by leveraging the fast response of regenerative braking (RBS), thereby improving braking performance. Zhu et al. [

8] optimized the distribution of longitudinal force, lateral force, and yaw moment to enhance vehicle stability, while supplementing the limitations of hydraulic braking with the fast response of electric braking, which shortened the braking distance. Chu et al. [

9] addressed the conflict between RBS and ABS in regulating hydraulic braking during electric vehicle braking and proposed an ABS-RBS coordinated control strategy that balanced control performance and real-time response. Wang et al. [

10] presented an adaptive fault-tolerant control strategy that generated additional tire forces and constrained yaw moments under braking system failures, thereby improving the tracking performance of target yaw rate and lateral velocity. Bai et al. [

11] developed a longitudinal-lateral stability coordinated controller for a battery electric vehicle equipped with distributed EMB braking and centralized drive, based on an MPC algorithm and a hierarchical control architecture, which integrated ABS, DYC, and other braking force distribution functions. Yu et al. [

12] focused on the integrated coordinated control of braking force distribution systems, including ABS, EBD, DYC, and RBS, within two-dimensional vehicle dynamics control.

For braking failure conditions in brake-by-wire vehicles, Wang et al. [

13] proposed a control strategy that redistributed the braking torque lost due to a single actuator failure among the remaining wheel braking systems while counteracting the additional yaw moment. Zhang et al. [

14] addressed braking failures in hub-motor electric vehicles and proposed a hierarchical fault-tolerant architecture that integrated regenerative braking and differential torque control to maintain both longitudinal and lateral stability. Feng et al. [

15] developed a control allocation algorithm that redistributed braking force and compensated the yaw moment through steering angle adjustment, thereby ensuring safe braking performance under partial or complete braking failures. Zhou et al. [

16] designed a dual-layer control architecture in which braking force redistribution was combined with yaw moment compensation based on sliding mode control, improving braking efficiency and stability under single-wheel failure in brake-by-wire systems. Tang et al. [

17] presented a stability control strategy for single-wheel braking failure, which reconstructed torque through predefined rules and applied a front wheel steering controller to maintain braking stability. For regenerative braking system (RBS) failure conditions, Wang et al. [

18] combined torque cut-off control, electro-hydraulic braking (EHB) torque compensation, and yaw stability control to achieve efficient coordination during regenerative braking failures. Fang et al. [

19] proposed a front-rear axle braking force compensation and distribution strategy that integrated EHB compensation control with deviation-assisted control, selecting appropriate electro-hydraulic brake compensation schemes according to the se-verity of regenerative braking failure and the location of the failed wheel. For EMB failure scenarios, Wu et al. [

20] proposed a multi-factor coupling fault-tolerant control strategy with a hierarchical architecture and dynamic braking force distribution. The HIL test results under a complete left-front actuator failure show that this strategy effectively handled the failure by reducing lateral displacement to 0.03 m while maintaining a deceleration of 3.7 m/s

2. Peng et al. [

21] designed a fault-tolerant electro-mechanical brake architecture using Markov chains and force redistribution, and the probability of a dangerous failure per hour for the system was 6.14 FIT in hard-ware-in-the-loop (HIL) tests, satisfying ASIL-D requirements.

In summary, most existing braking force coordination studies employ a hierarchical control architecture integrating EBD, ABS, and DYC subsystems to coordinate braking demands based on LQR control and phase-plane stability boundaries, with optimization typically based on SQP algorithms and slip ratio or adhesion coefficient targets. However, existing research on braking force coordination mainly focuses on coordination under normal braking conditions, EMB redundancy backup during RBS failure, coordination of the remaining wheel braking forces during EMB failure, or cooperative control with steering systems. While mechanical and RBS can form mutually redundant relationships, research on braking force coordination strategies under mechanical braking failure compensated by RBS redundancy remains limited. Furthermore, above mentioned braking coordination control method based on LQR control and phase-plane stability boundaries is very difficult to dynamically handle conflicts between ABS and DYC, and it is also not applicable to multi-wheel sequential failures.

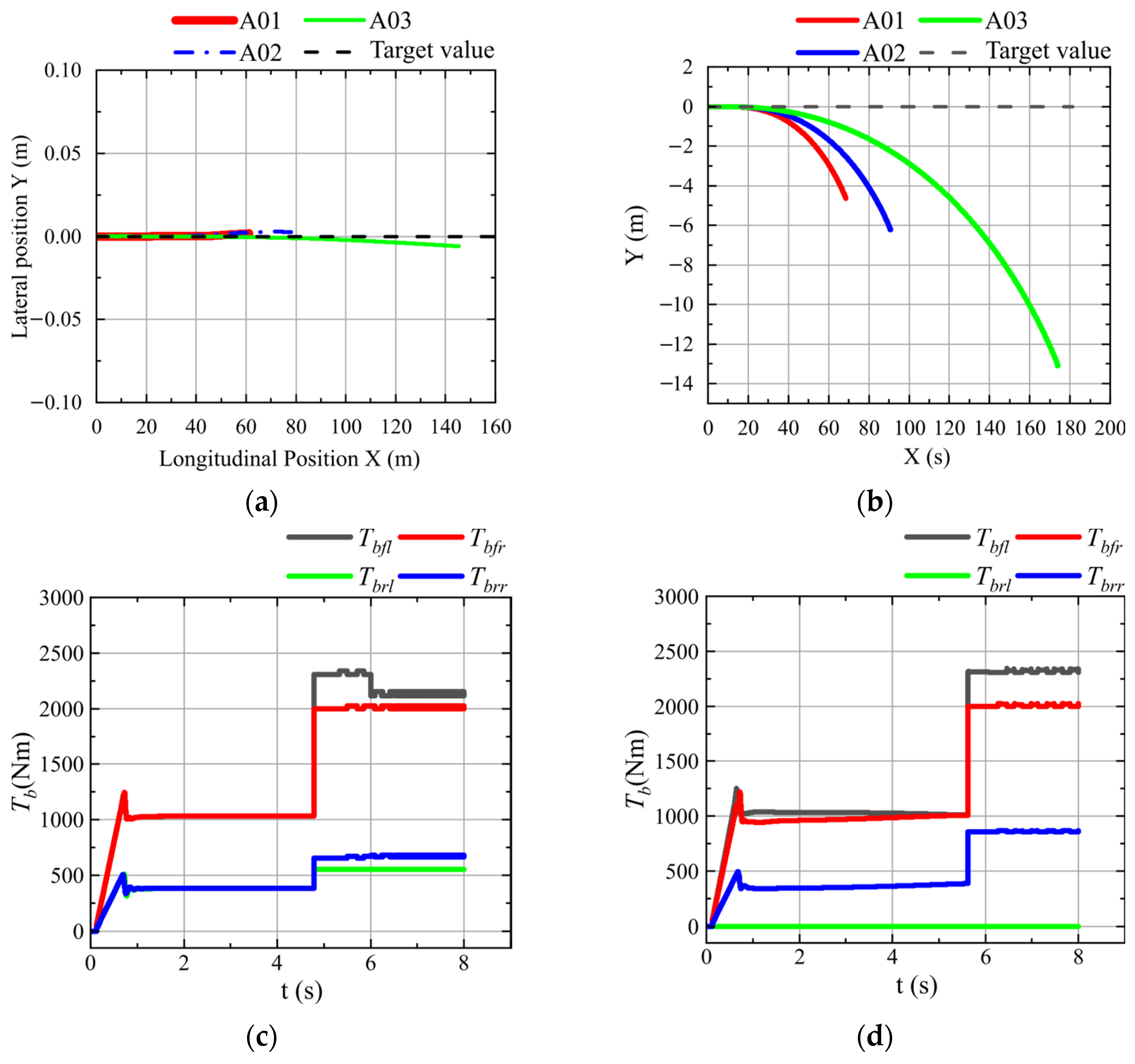

To address these issues, this paper proposes a braking force coordination control strategy for electric vehicles based on a hierarchical control architecture, aiming to resolve conflicts among dynamic braking force allocations during coordination of ABS, EBD, DYC, and RBS, as well as to compensate braking force dynamically under brake actuator failure. The proposed architecture consists of three layers: the upper-layer controller, which integrates EBD, DYC, and the available electric braking force computation module while establishing DYC-ABS coordination rules; the mid-layer controller, which incorporates a braking force limited state evaluation module and integrates ABS functionality to construct a three-level braking force reconstruction mechanism based on the temporal sequence and spatial position of failures; and the lower-layer controller, which coordinates longitudinal and lateral braking forces in response to actuator failure states. The main contributions of this paper are as follows.

A dynamic computation model of the braking force limited coefficient is established to support braking force reconstruction and coordination.

A braking force coordination control strategy for electric vehicles under actuator failure conditions is proposed, employing RBS as a full redundant braking actuator, which effectively improves braking stability and safety under fault scenarios.

3. Design of Braking Force Coordination Control Strategy

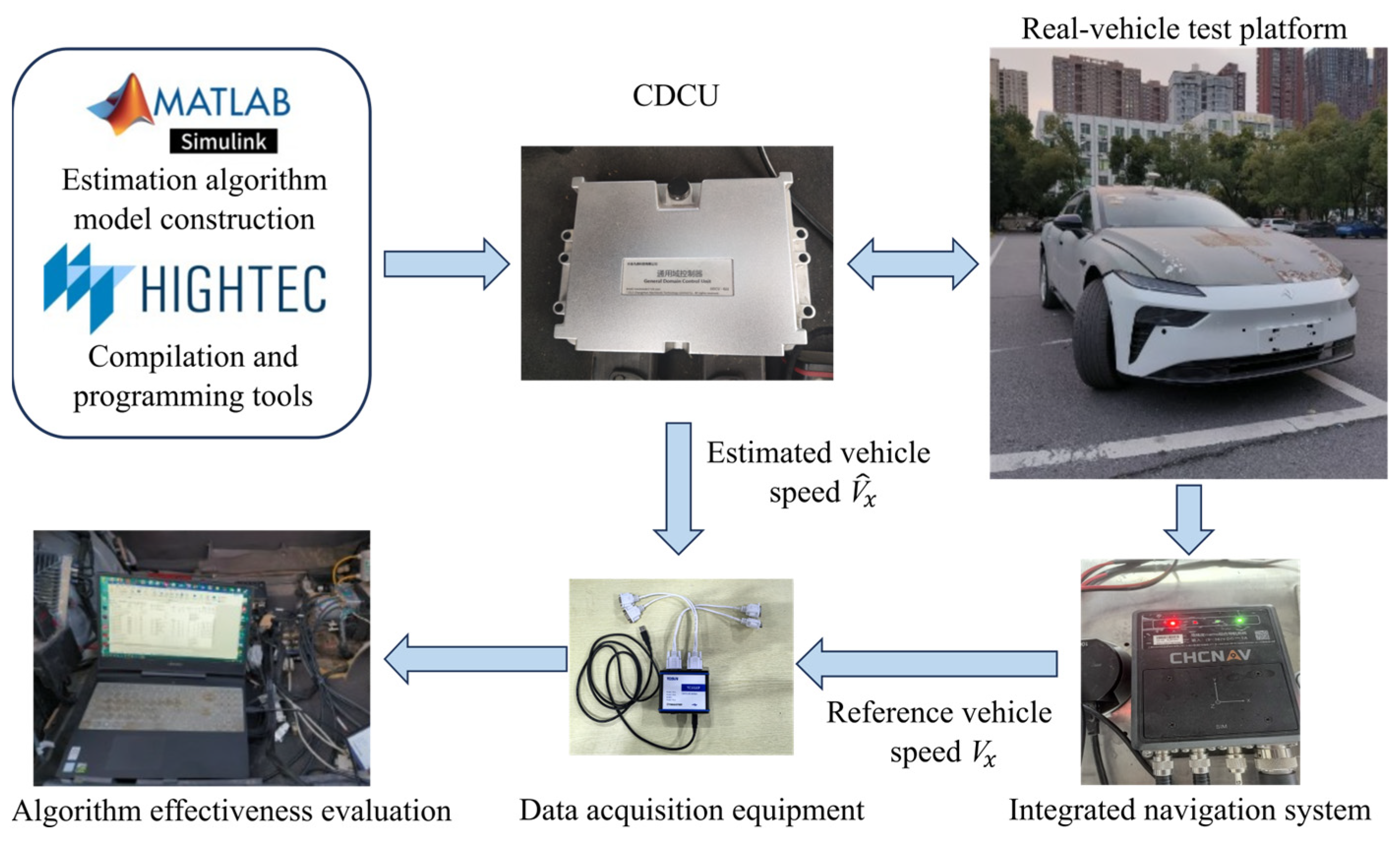

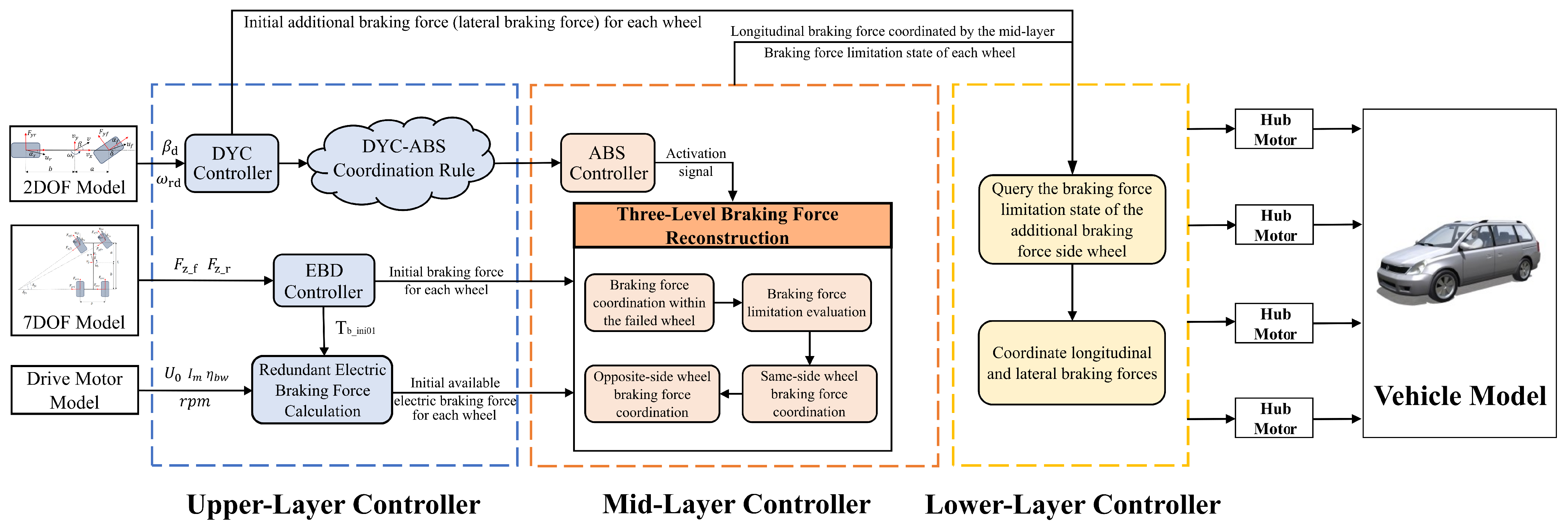

To address braking instability under actuator failure conditions, this paper proposes a braking force coordination control strategy based on a hierarchical control architecture, as shown in

Figure 13. The strategy consists of three layers: The upper-layer controller integrates EBD, DYC, and the available electric braking force computation module while establishing DYC-ABS coordination rules. The mid-layer controller includes braking force limited state evaluation and integrates ABS functionality to construct a three-level braking force reconstruction mechanism based on failure timing and location. The lower-layer controller coordinates longitudinal and lateral braking forces according to actuator failure states. Since EMB replaces mechanical and hydraulic components with electronic devices, concerns regarding reliability and insufficient redundancy remain [

23]. Therefore, this study mainly addresses EMB failure scenarios.

3.1. Upper-Layer Controller

The proposed upper-layer controller is composed of the EBD, DYC, and the available electric braking force computation module, as well as the DYC–ABS coordination rules. The specific analysis is presented as follows.

3.1.1. EBD Controller

Since the EBD requires the driver’s desired braking force, a driver model is designed to track the target vehicle speed, essentially functioning as a longitudinal speed tracking controller. Proportional–integral–derivative (PID) control is employed to minimize the speed error between the desired and actual vehicle speeds and to generate the required longitudinal torque.

EMB outputs the initial braking force for each wheel based on the driver’s desired braking force. In this study, the EBD controller is designed based on a dynamic axle-load and wheel-speed deviation correction method. The initial front-rear braking force distribution coefficient is first determined using the dynamic vertical loads of each wheel. Then, is corrected according to the wheel-speed deviation between the front and rear wheels, resulting in the final braking force distribution coefficient .

Based on the 7-DOF vehicle dynamics model, the vertical load on the front and rear axles can be obtained as follows:

where

and

are the vertical loads acting on the front and rear axles, respectively.

The initial braking force distribution coefficient is given by:

During vehicle braking, wheels with lower speeds exhibit a greater tendency to lock up compared to those with higher speeds. Wheel speed can reflect this locking tendency, and the ratio of the wheel speeds between the front and rear axles can be utilized to correct the initial coefficient .

The front-rear wheel-speed ratio

is defined as:

The ideal front-rear wheel-speed ratio is

, and the wheel-speed ratio error is defined as:

Using a discrete PID algorithm, the front-rear wheel-speed ratio error is employed to provide feedback compensation for

:

where

is the transformed value of

after the z-domain conversion,

,

, and

are the weighting coefficients of the proportional, integral, and derivative terms, respectively, and

is the filtering factor, with

.

The front-rear braking force distribution coefficient must also satisfy the following constraint:

Based on the corrected front-rear braking force distribution coefficient , the system limits the braking force of the rear axle to ensure that the braking force distribution between the front and rear brake actuators reaches the ideal ratio.

3.1.2. DYC Controller

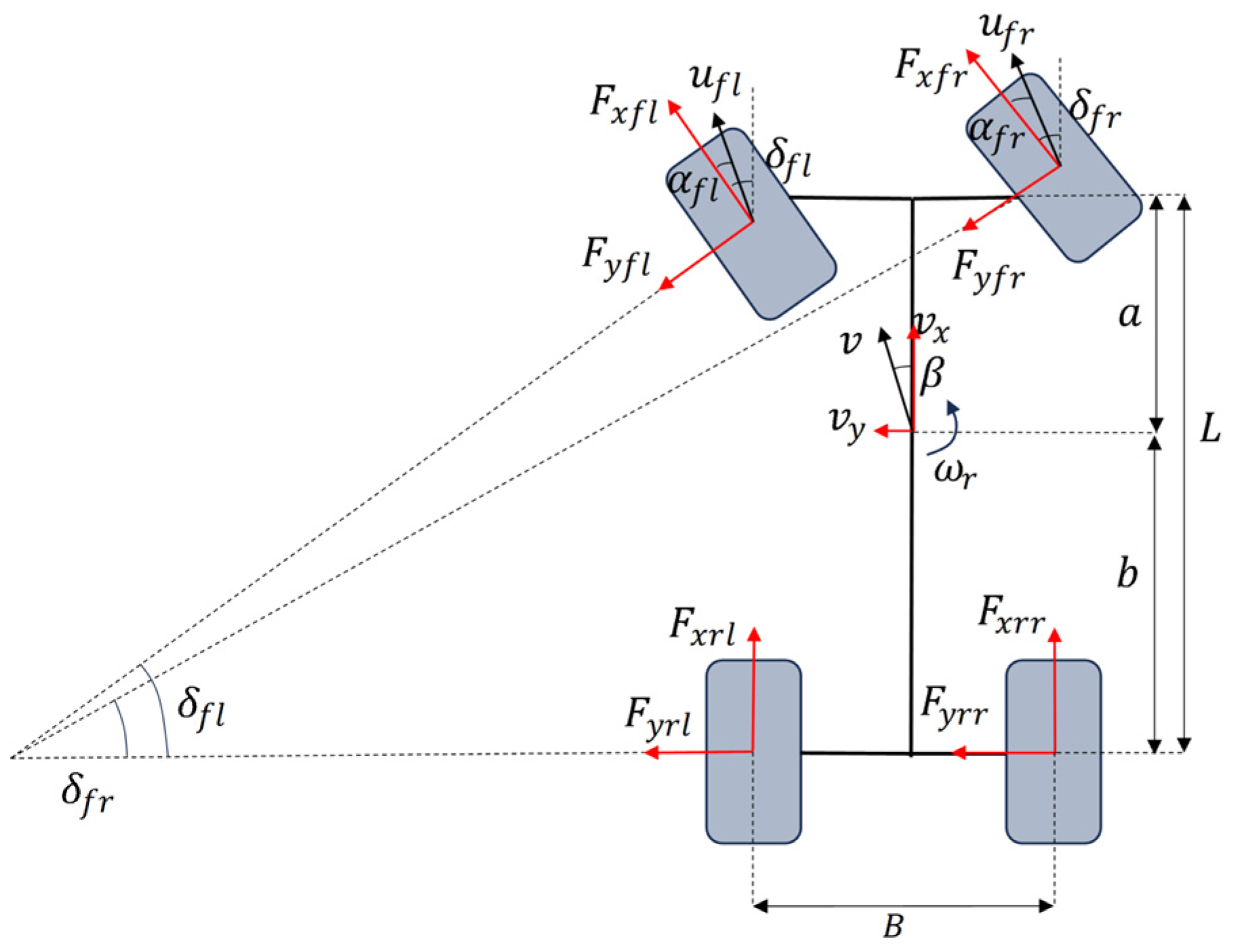

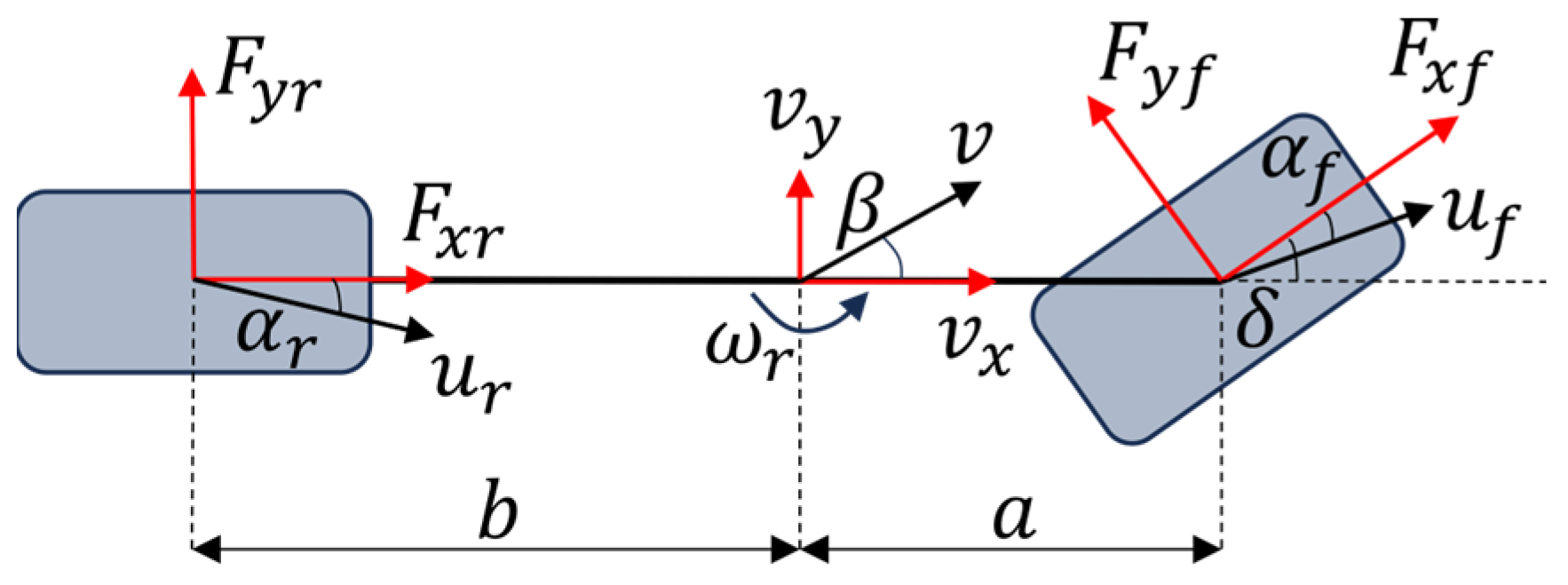

The DYC system calculates the required additional yaw moment using an LQR controller, and this moment is allocated through an additional braking force distributor. By applying unilateral braking, the corresponding additional yaw moment is generated to suppress understeer or oversteer tendencies during vehicle cornering.

Considering the neutral-steer steady-state characteristics represented by the 2-DOF linear vehicle dynamics model, the model outputs, namely the sideslip angle at the vehicle’s center of gravity

and the yaw rate

, are constrained dynamically based on the road adhesion coefficient μ, thereby forming the theoretical reference values for the closed-loop DYC control system.

where

is the stability factor of the vehicle during steering.

The reference values for the sideslip angle at the center of gravity and the yaw rate are given as follows:

The state-space representation is derived from Equation (17) as follows:

where

and

, and

is the additional yaw moment.

Let

and

, and Equation (19) can be rewritten as:

The optimal control input

is given as follows:

where

and

are the weighting matrices for the state vector

and the input vector

, respectively.

The additional yaw moment applied to the front and rear wheels is distributed according to the rule specified in Equation (22).

When

is positive, the additional braking force is applied to the left-side wheels according to the following rule:

When

is negative, the additional braking force is applied to the right-side wheels according to the following rule:

3.1.3. Computation of Available Electric Braking Force

When the electric braking mode is activated on a specific wheel, such as during EMB failure conditions where RBS functions as a redundant braking system, the redundant electric braking force calculation module delivers both the initial electric braking force and the available electric braking force for all four wheels. Conversely, when the electric braking mode is not activated on a wheel, such as when it is operating under EHB or EMB actuation states, both the available electric braking force and the initial electric braking force for that wheel remain zero.

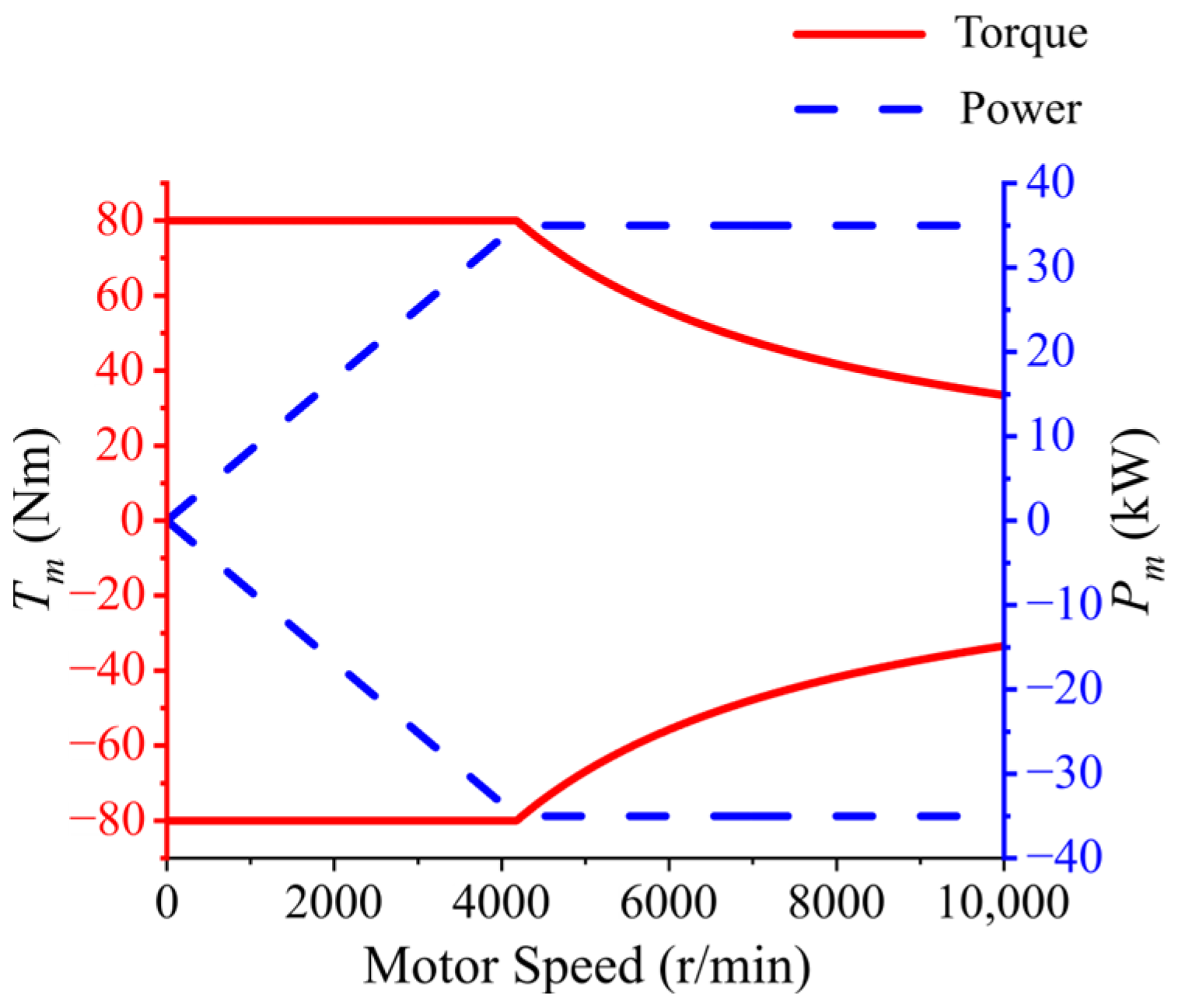

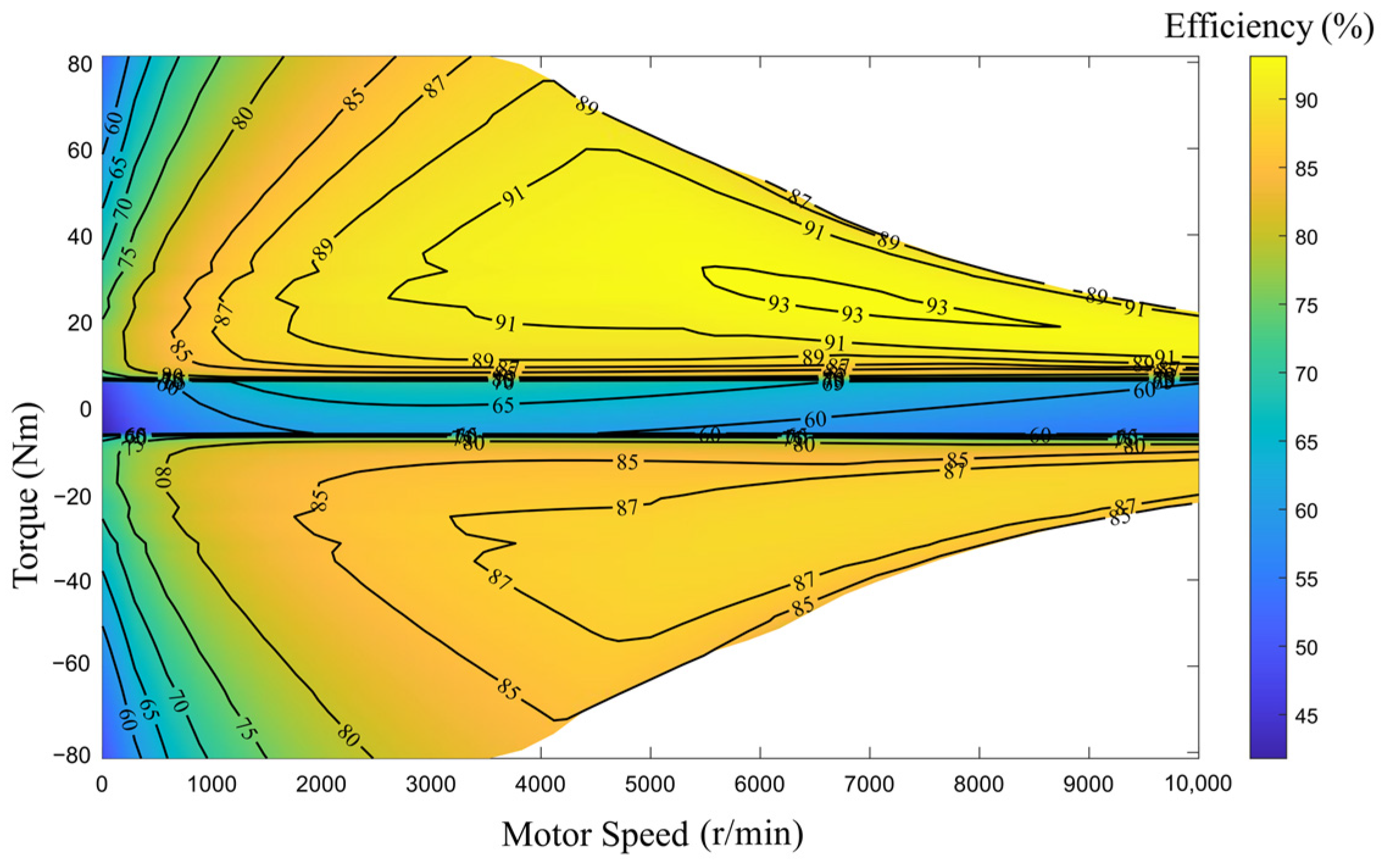

The available output power of the motor under regenerative braking conditions is given as follows:

where

is the rated voltage of the power battery,

is the dynamic maximum charging current of the power battery, and

is the dynamic operating efficiency of the drive motor for a given wheel.

The mechanical power required by the load is given as follows:

where

is the torque corresponding to the initial braking force on a given wheel, and

is the rotational speed of the drive motor.

When

, the motor braking torque can fully meet the demand, and the motor braking torque is set to the target value as follows:

The corresponding available electric braking torque of the motor is given as follows:

When

, the motor braking torque is limited and is determined by the maximum available power.

Due to insufficient motor power, the available electric braking torque is zero.

Thus, the initial electric braking force and the initial available electric braking force are calculated as shown in Equation (31).

When the RBS on a failed wheel cannot generate sufficient target braking force, the coordination mechanism is activated to engage the mechanical brakes on functional wheels, thereby compensating for the deficient braking force or executing relevant dynamics control actions.

3.1.4. Coordination Strategy Between DYC and ABS

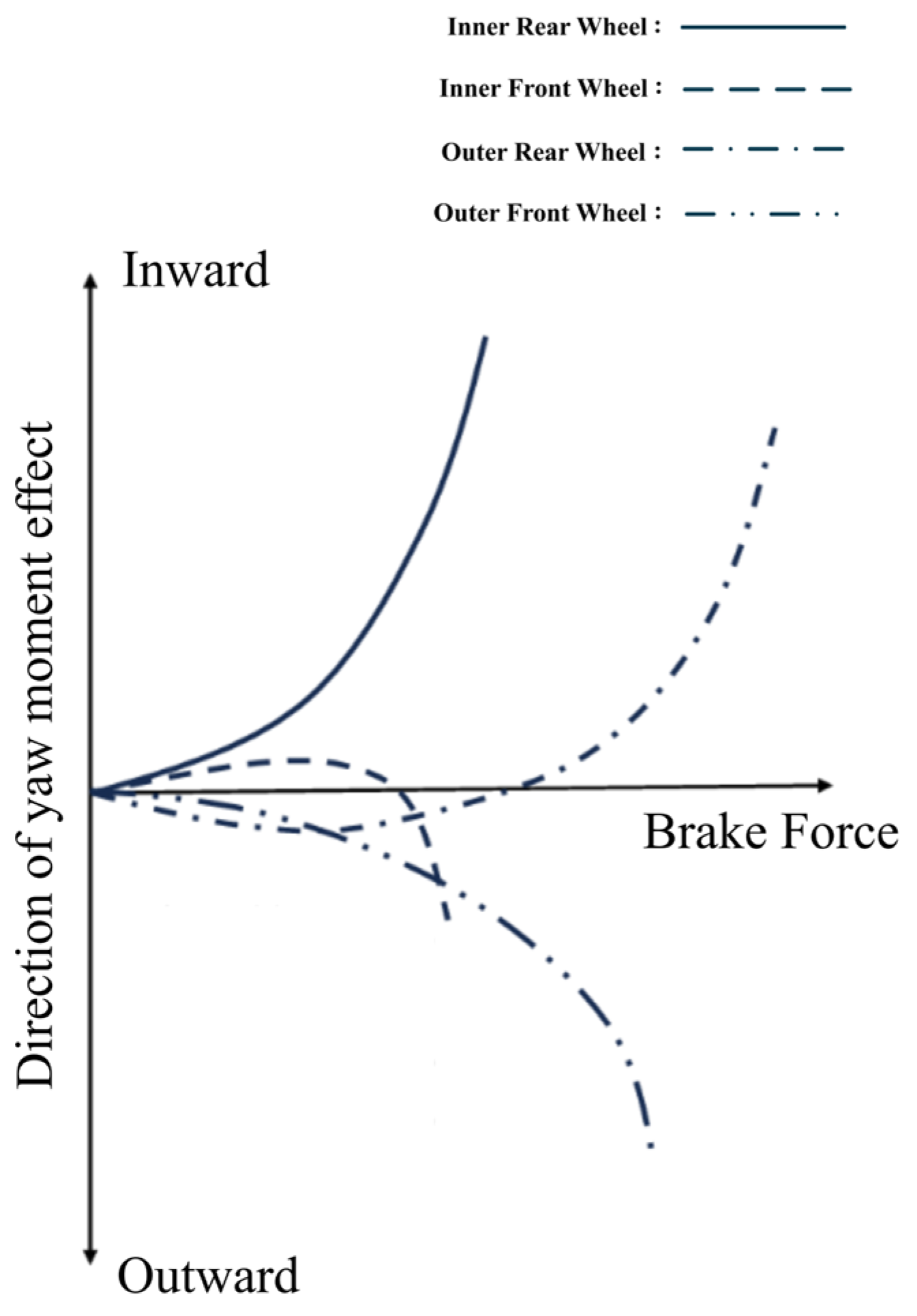

The application of excessive additional braking force by the DYC system on a wheel may trigger the ABS control system, necessitating coordination between DYC and ABS. The DYC system generates the additional yaw moment through unilateral braking, where the left side is defined as the inner wheel during a left turn and vice versa [

24]. As shown in

Figure 14, braking should be prioritized on the inner rear wheel in understeer conditions, whereas the outer front wheel should be prioritized in oversteer conditions. The braking force distribution for the inner front and outer rear wheels must adhere to the adhesion ellipse theory. Based on this, the DYC system control strategy is established as follows: actuators for the inner rear and outer front wheels may adopt an unrestricted regulation strategy without activating the ABS control module; whereas the inner front and outer rear wheels require a restricted regulation strategy, where the ABS control is synchronously activated when the wheel slip ratio exceeds the critical threshold. The coordination control rules of DYC and ABS are provided in

Table 1.

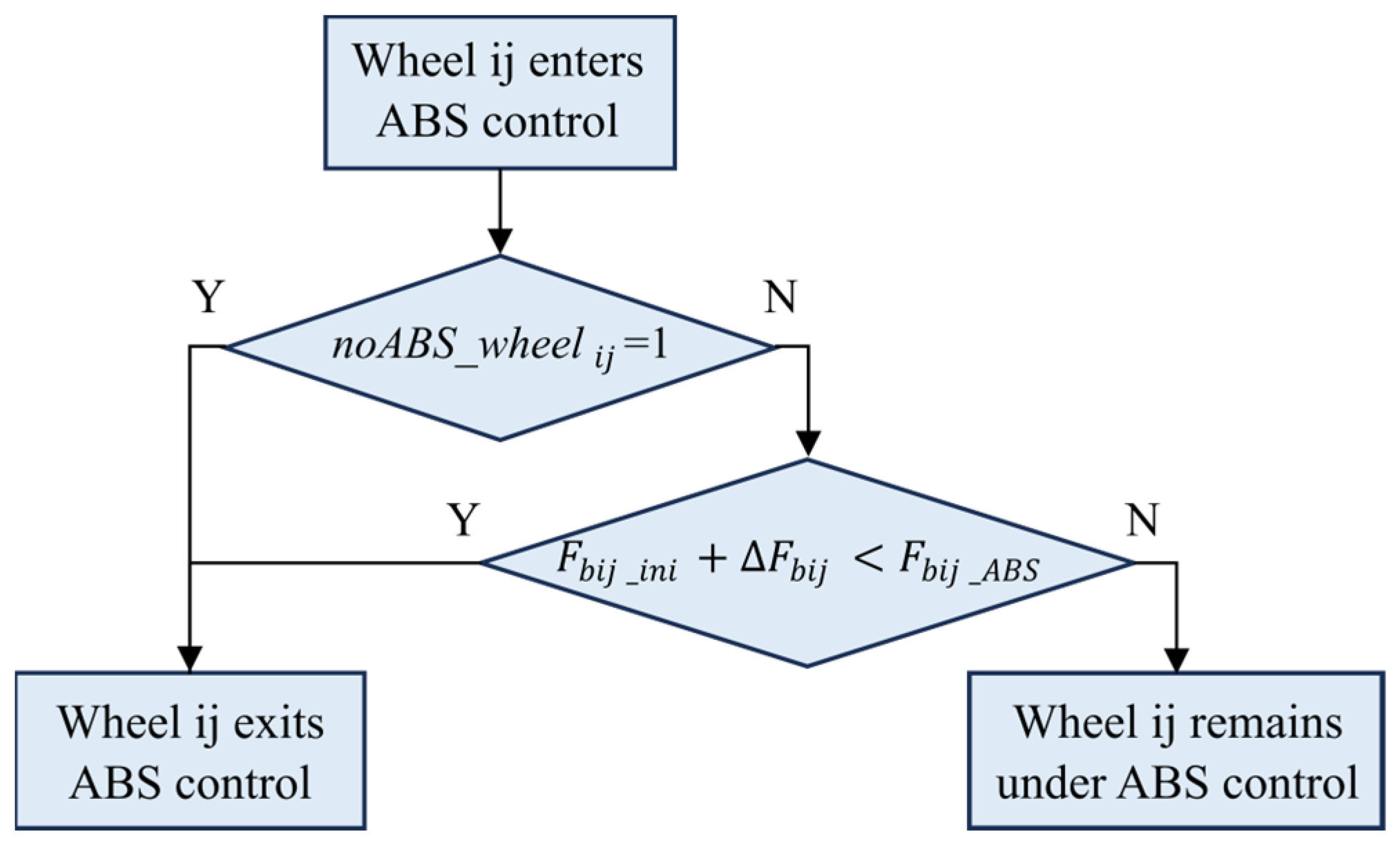

When the slip ratio of a wheel increases due to the additional braking force applied by the DYC system, triggering ABS intervention, the ABS control should be promptly deactivated after the demand for additional braking force ceases and no braking demand exists for that wheel. The coordination exit strategy between ABS and DYC is illustrated in

Figure 15, where

is the target braking force output by the ABS controller for ij-wheel, and

is the ABS activation signal for ij-wheel. When

, the ABS control is not activated for the corresponding wheel.

Eventually, the upper-layer controller outputs to the middle/lower layers the initial braking forces for all four wheels, the initial electric braking forces, the available electric braking forces, and the additional braking forces and the signal.

3.2. Mid-Layer Controller

The proposed mid-layer controller is composed of the ABS and the braking force limited state evaluation module, and a three-level braking force reconstruction mechanism based on the temporal sequence and spatial position of failures. The detailed analysis is provided below.

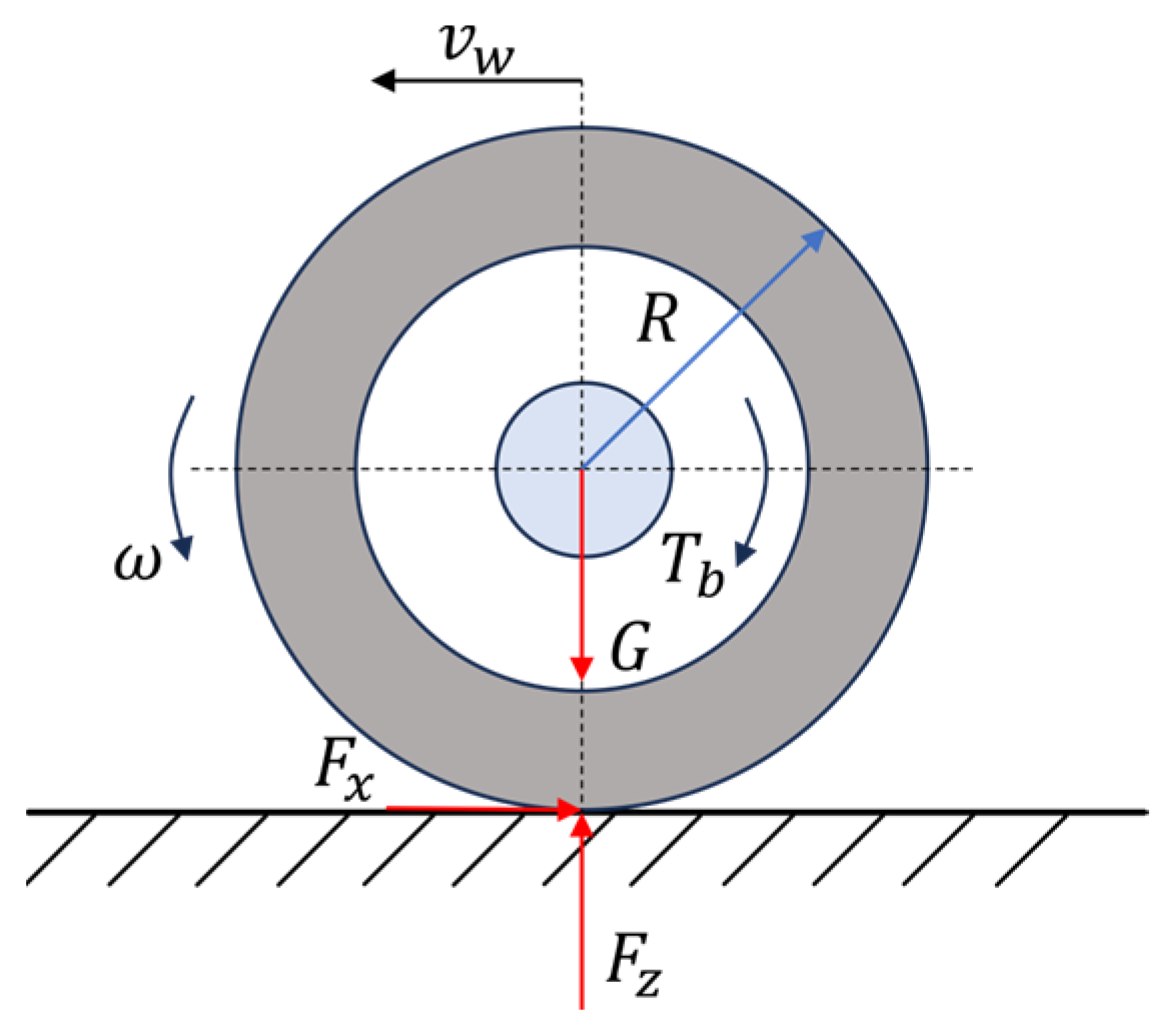

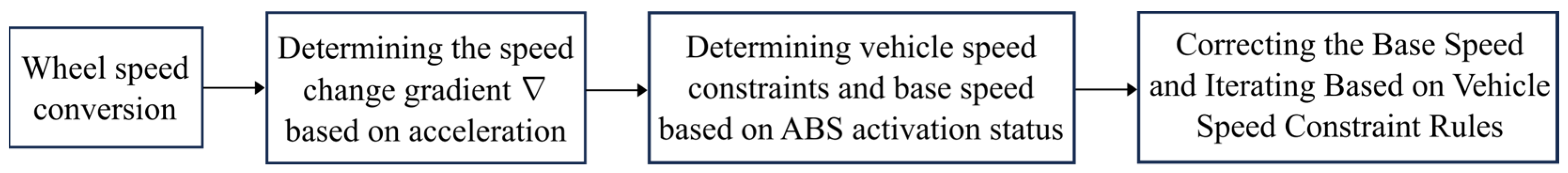

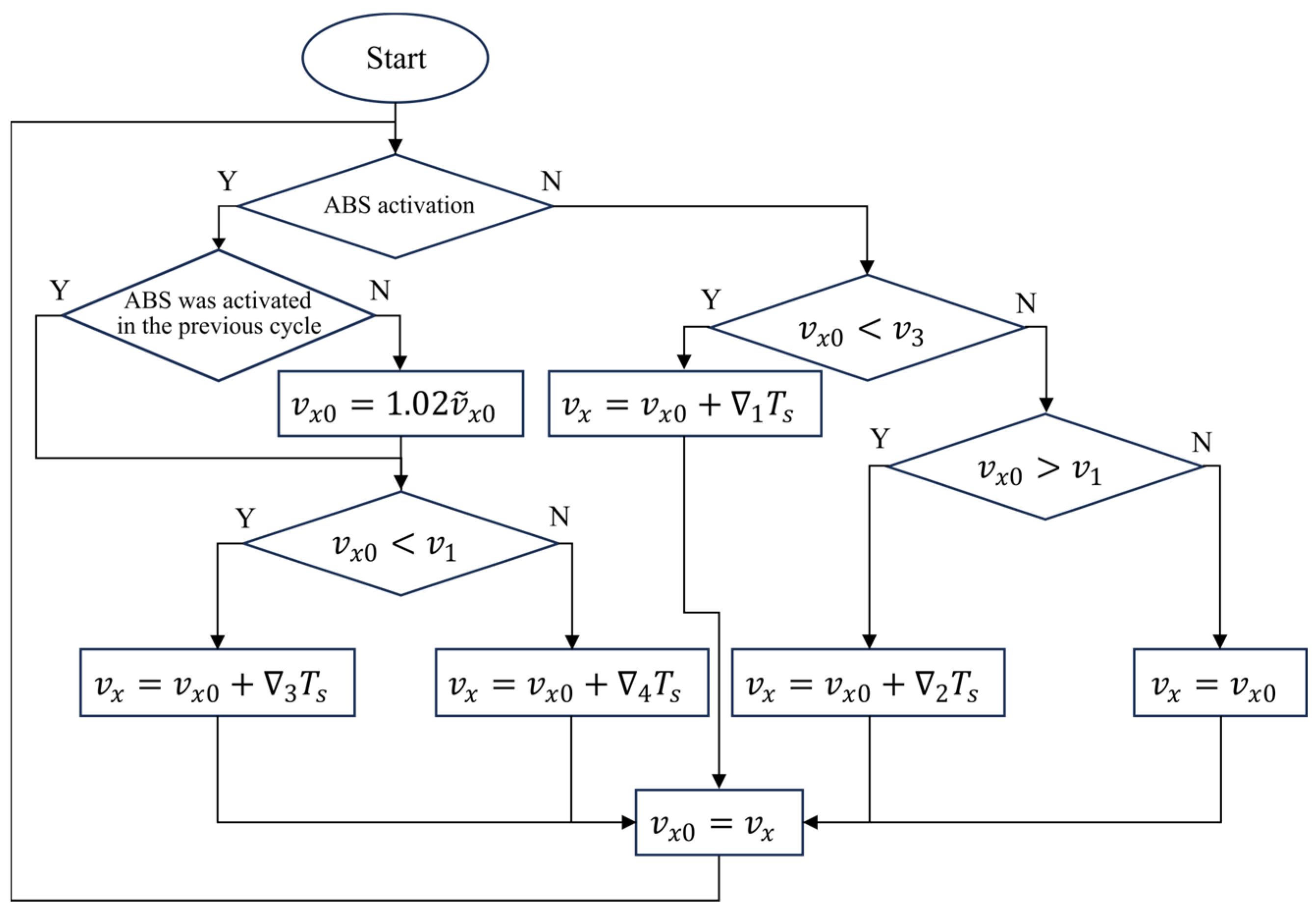

3.2.1. ABS Controller

An ABS control strategy is established based on Sliding Mode Control (SMC). The dynamic model of the wheel during braking is shown in

Figure 4. The wheel center velocity

, the wheel angular velocity

, and the wheel slip ratio

are selected as the state variables, i.e.,

,

,

, with the braking torque

as the input. The state-space representation is given by Equation (32).

The state-space representation can be reformulated as follows:

The error tracking function is defined as follows:

where

,

is the target slip ratio, and

.

The Lyapunov function is defined as follows:

Thus, , .

An exponential reaching law is selected.

where

,

, and

is the sign function of.

Based on Equation (36), the control law for the braking torque

can be derived as follows:

To mitigate the chattering issue in the sliding mode controller, the sign function is replaced with a saturation function. This substitution ensures a smooth transition of the control input when the error tracking function changes sign. The modified control law for

after incorporating the saturation function is given as follows:

3.2.2. Three-Level Braking Force Reconfiguration

The mid-layer controller primarily coordinates the braking force through its three-level braking force redistribution function, adhering to the principle of maintaining equal braking forces on both sides during redistribution. When EHB or EMB serves as the brake actuator, control is managed by a conventional ABS controller; while when RBS acts as the brake actuator, control is implemented by the RBS_ABS controller.

When a wheel does not trigger ABS and enters the failure mode, a three-level braking force redistribution is executed in four steps: (1) Braking force coordination within the failed wheel; (2) Braking force limited state evaluation; (3) Same-side wheel braking force coordination; (4) Opposite-side wheel braking force coordination.

When the wheel triggers ABS and enters the failure mode, due to EMB failure, the RBS_ABS controller is utilized for control. Once the wheel enters the ABS control state, it cannot participate in the braking force coordination within the failed wheel. Therefore, the ABS activation status and the braking force of the ABS-activated wheels are directly input into the braking force limited evaluation module, which subsequently provides a reference for the following brake force coordination process.

- (1)

Braking force coordination within the failed wheel: when EMB fails and the RBS is used as the redundant braking system, the available electric braking force of the failed wheel is assessed. If the initial available electric braking force of the failed wheel is greater than zero, the failed wheel can achieve full redundant braking. However, if the initial available electric braking force of the failed wheel is less than or equal to zero, it indicates that the electric braking force provided by the drive motor has reached its limit, and full redundant braking cannot be achieved within the failed wheel. In this case, the coordination of the same-side wheel is requested to compensate for the missing brake force of the failed wheel.

- (2)

Braking force limited state evaluation: before performing the same-side wheel braking force coordination control, it is necessary to determine the extent of brake force limitation for each wheel. The rules for determining the braking force limited weight are shown in

Table 2, where

is the braking force limited weight for each wheel. When designing the specific values for the braking force limited weight, it is important to note that when the wheels on both sides are in different states, the sum of the braking force limited weights for the single-side wheels should not be equal, as this would affect the braking force coordination of the opposite-side wheel. A braking force limited weight less than 0.5 indicates an unrestricted brake force state, greater than 0.5 indicates a fully limited brake force state, and equal to 0.5 indicates a partially limited brake force state. The selection of weight values is intended to distinguish the severity of the failure conditions.

- (3)

Same-side wheel braking force coordination: when the backup braking force available from the failed wheel is limited and full redundant braking cannot be achieved, the coordination of the same-side wheel braking force is requested. This coordination allows the wheel with unrestricted brake force on the same side to compensate for the missing brake force portion.

The same-side wheel braking force coordination module first evaluates the braking force limitation coefficient of the same-side front wheel. If the limitation coefficient

, indicating that the wheel is in an incompletely limited braking state, the same-side front wheel compensates for the required braking force. If the front wheel is in a fully limited braking state, coordination with the opposite-side wheel is requested to ensure equal braking forces on both sides.

where

and

are the braking forces requested from the opposite-side wheels for coordination on the left and right sides, respectively;

and

are the initial braking forces of the rear-left and rear-right wheels;

and

are the initial electric braking forces of the rear-left and rear-right wheels, respectively.

- (4)

Opposite-side wheel braking force coordination: when the braking force of the front wheel on the same side as the failed wheel is in a fully limited state, the coordination of the opposite-side wheel braking force should be requested.

The opposite-side wheel braking force coordination module first compares the braking force limited weights of the left and right wheels. The side with the higher limited weight indicates a more severe braking failure situation, with a smaller available brake force coordination space. Therefore, the braking force coordination request from the side with the larger braking force limited weight is taken as the target coordination braking force , and the wheel on the side with the smaller braking force limited weight responds to this target coordination braking force. If the braking force limited weights on both sides are equal, then .

Next, the braking force limited state of the wheel with the smaller limited weight is checked. If both wheels are fully limited in braking force, opposite-side braking force coordination cannot be performed. If only one wheel is in a non-fully limited braking force state, that wheel will handle the coordination. If both wheels have non-fully limited braking forces, the SQP algorithm is used to coordinate with the wheel on the side with the smaller limited braking force. The side with the larger braking force limited weight is the coordinated side, while the side with the smaller limited weight is the coordinating side. If is less than zero, indicating that the coordinated side’s braking force is fully limited, the coordinating wheel must reduce its braking force to ensure that the braking forces on both sides are balanced. Since maintaining directional stability is generally more important than minimizing braking distance, the coordinating wheel can reduce some of its braking force to ensure stability, but the reduction should not exceed 20% of its original braking force.

When coordinating braking force based on the SQP algorithm, the optimization criterion is to minimize the total tire force utilization on that side of the vehicle, adjusting the front and rear braking forces accordingly. The expression for tire force utilization is as follows:

where

and

are the front, rear, and left, right wheels, respectively;

,

, and

are the longitudinal force, lateral force, and vertical load on each wheel, respectively;

is the peak tire-road adhesion coefficient for each wheel. Since the lateral force is generally uncontrollable, only the distribution of longitudinal force is optimized [

25]. When using the SQP algorithm to coordinate the braking forces, the wheels on the side with the smaller braking force limited weight have not yet activated ABS. In this case, the braking force is equal to the ground adhesion force. The optimization objective function is to minimize the sum of the squared tire force utilization on the side with the smaller braking force limited weight:

where

is the braking force of each wheel.

The constraint function is shown below:

The mid-layer controller ultimately outputs the coordinated braking force for each wheel, along with the braking force limited state signals, which are used to control the lower-layer controller.

3.3. Lower-Layer Controller

The lower-layer controller primarily coordinates the longitudinal braking forces from the mid-layer controller with the additional braking forces output by the upper-layer controller. The process begins by checking the braking force limited state of the wheel on the side where the additional braking force is applied (left or right). If both wheels on that side have fully limited braking forces, the initial additional braking force for the front and rear wheels cannot be coordinated. If only one wheel has a non-fully limited braking force, the additional braking force is applied by the wheel with the non-fully limited braking force. If both wheels have non-fully limited braking forces, the additional braking forces and are applied separately to the front and rear wheels. Here, and represent the initial additional braking forces for the front and rear wheels, respectively. Specifically, when , and represent the initial additional braking forces for the left-side front and rear wheels; when , and represent the initial additional braking forces for the right-side front and rear wheels.

Finally, the target braking force for each wheel is determined by the lower-layer controller and delivered to the corresponding brake actuator.