1. Introduction

Wind turbines serve as essential components in modern renewable energy infrastructure, especially in offshore and coastal regions where wind resources are plentiful. However, their drivetrains, comprising gearboxes, generators, and other rotating elements, operate under highly dynamic loads and harsh marine conditions that accelerate wear and promote fault development [

1]. Faults in wind turbine drivetrains are generally grouped into three categories: (a) electrical faults, including generator winding failures and insulation breakdowns; (b) mechanical faults, which are the most frequent in practice and typically arise in gearboxes, bearings, and shafts; (c) environmental and control-related faults, such as those caused by wet and corrosive offshore environments or control system malfunctions [

2].

Among these, mechanical faults in drivetrain rotating components are especially critical because they often escalate into severe damage and are associated with long downtime and high maintenance costs if not identified at an early stage [

3]. As these faults typically manifest through changes in dynamic behaviour, they can be detected most effectively through vibration analysis [

4]. Therefore, vibration signals remain one of the most informative indicators of such problems due to their sensitivity to structural and dynamic changes [

5].

Traditional vibration-based condition monitoring methods typically rely on signal processing techniques, and the main purpose of signal processing is to cancel the noise contained in the vibration signals and then extract the fault-related features based on prior knowledge. For example, the study in [

6] employed a hybrid strategy combining variational mode decomposition (VMD), correlation evaluation, and wavelet-threshold filtering to suppress noise present in the vibration data. In [

7], the proposed method extracts instantaneous frequency features from vibration signals to detect different fault types of rolling bearings when the rotational speed varies over time. Usually, such signal processing workflows are not only laborious and time-consuming but also heavily reliant on the operator’s expertise and experience.

In recent years, artificial intelligence (AI) techniques have been increasingly integrated into machine condition monitoring. Compared with traditional vibration-based condition monitoring methods that rely on professional knowledge on feature extraction and fault diagnosis, AI-assisted approaches can automatically learn patterns or features from vibration signals and distinguish between different types of faults [

8]. In previous years, a variety of machine learning algorithms, such as Support Vector Machines (SVMs), Logistic Regression, and K-Nearest Neighbours (KNNs), have been widely used for fault detection based on extracted features from vibration signals [

9]. Decision tree, as an example, has been one of the most common and widely used traditional machine learning models used since 1980s [

10]. In [

11], the authors apply decision tree algorithms for wind turbine structure condition monitoring by leveraging their fast learning, ease of interpretation, ability to support clear fault tracing, and strong performance when both error rate and training speed are considered. A further example of decision tree’s application is presented in [

12], where it is used for planetary gearbox condition monitoring, which highlights its capability for motor-driven system condition monitoring using statistical features. Recent research has also demonstrated the effectiveness of decision trees for lightweight fault classification tasks implemented on edge devices [

13]; a fine decision tree classifier was deployed on a microcontroller to enable immediate detection of abnormalities in rotating machinery using extracted features. However, despite their popularity and advantages, decision tree-assisted condition monitoring methods have some obvious drawbacks. For example, decision trees tend to overfit easily during training, resulting in poor generalization [

14], and this is especially problematic in the cases where noisy data is used, because these kinds of models are excessively sensitive to slight changes in training sets [

15]. To address these weaknesses, Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) has been proposed as an enhanced tree-based ensemble learning method. In [

16], the XGBoost model is used in conjunction with the Mel Frequency Spectral Coefficient features extracted from vibration data for the classification of roller bearing faults. In [

17], the performance of the XGBoost model was assessed against that of other classic machine learning models and showed the highest accuracy for bearing faults.

In addition to performance, interpretability is another key advantage that decision tree-based models have in condition monitoring applications [

18]. These tree-based models offer transparent and rule-based reasoning by constructing explicit paths from input features to output targets [

19]. This makes them particularly useful in applications where interpretability and fault traceability are important. The most common scenario where the interpretability of tree-based models is feature selection, where the importance of different features will be calculated and ranked, allowing only the features of high importance to be used for further analysis. In [

20], the authors applied XGBoost with feature importance ranking to reduce redundant sensor data and improve fault classification performance. And in [

21], the authors used XGBoost model to rank the importance of more than 300 statistical features extracted from vibration and cutting force signal and selected only 14 features in the training stage, significantly improving the training efficiency and prediction accuracy. However, tree-based models including XGBoost still have a key drawback: they rely heavily on artificially designed indicators, such as statistical metrics. These indicators cannot guarantee that they can effectively distinguish the health status and fault type of the machine.

More recently, deep learning (DL) models have been increasingly used attributed to their ability to learn complex patterns from raw or processed vibration signals. For example, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are typically efficient in capturing spatial patterns across different vibration signal domains [

22]; Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) are well suited for handling sequential inputs, such as time-domain vibration signals [

23]. Transformers, with their multi-head attention mechanisms, have proven effective for handling complex signals and capturing dependencies from large data segments [

24]. To overcome the reliance on artificially designed features, recent studies have increasingly turned to DL approaches that are capable of identifying meaningful patterns directly from complex or noisy data with high generalizability [

25]. Among these architectures, CNNs are particularly effective at identifying informative structures within raw signal data. One-dimensional (1D) CNNs usually operate directly on raw time-series data. For example, in [

26], a 1D CNN was proposed to process raw vibration and phase current signals for detecting faults in bearings. In [

27], a 1D CNN was used as the feature extractor for vibration signals in a Zero-Shot Learning (ZSL) framework, where Semantic Feature Space mapping was adopted for intelligent fault detection of unseen faults. In contrast, 2D CNNs are usually applied to transformed representations of raw signals, such as frequency maps, time-frequency maps, or images generated by self-defined approaches from raw signals. In [

28], a 2D CNN was employed to extract grayscale images from enhanced frequency maps of vibration signals, achieving high classification accuracy using undersampled signals. On the other hand, the Transformer model, which was originally proposed in [

29], has also demonstrated high performance to capture long-range dependencies through self-attention mechanisms. In [

30], a transformer-based model was proposed to estimate the remaining useful life of the bearing lubricant using the frequency domain of the vibration signal. In [

31], a transformer model was used for rolling bearing fault diagnosis, using time–frequency representations of wavelet transforms to capture non-stationary signal patterns and long-range dependencies.

By integrating the strength of CNN in capturing local patterns with the ability of modelling global dependency in transformer-based architectures, recent studies have proposed hybrid models, CNN–Transformer models. In [

32], a CNN–Transformer multitask model was proposed for simultaneously performing both bearing fault diagnosis and severity assessment, utilizing the local feature extraction ability of CNNs and global sequence modelling ability of Transformer to improve DL model robustness. In [

33], the authors developed a CNN–Transformer model to enable fault identification in rotating equipment across a range of operating states. Similarly, CNNs were used for multi-scale feature extraction, and Transformer blocks were introduced to link the relationship between fault patterns and fault types.

While DL models and their combined architectures have achieved popularity in vibration-based condition monitoring, they also present limitations. To extract meaningful patterns from a complex and noisy raw vibration signal or its representations, these models are usually high in complexity, involving large number of parameters and layers, that makes them difficult to design, train, and fine-tune [

34]. In addition, the scarcity of useful data and their reliance on large training data and computationally intensive operations can pose significant challenges in terms of resource availability, resource consumption, and training time. These factors may restrict their real-world applicability, especially on real-time or resources-limited platforms such as edge devices [

35]. Therefore, it is necessary to find a practical way to utilise the powerful capabilities of DL models while keeping them structurally simple and computationally efficient, as well as enhance their interpretability. This motivates the research reported below.

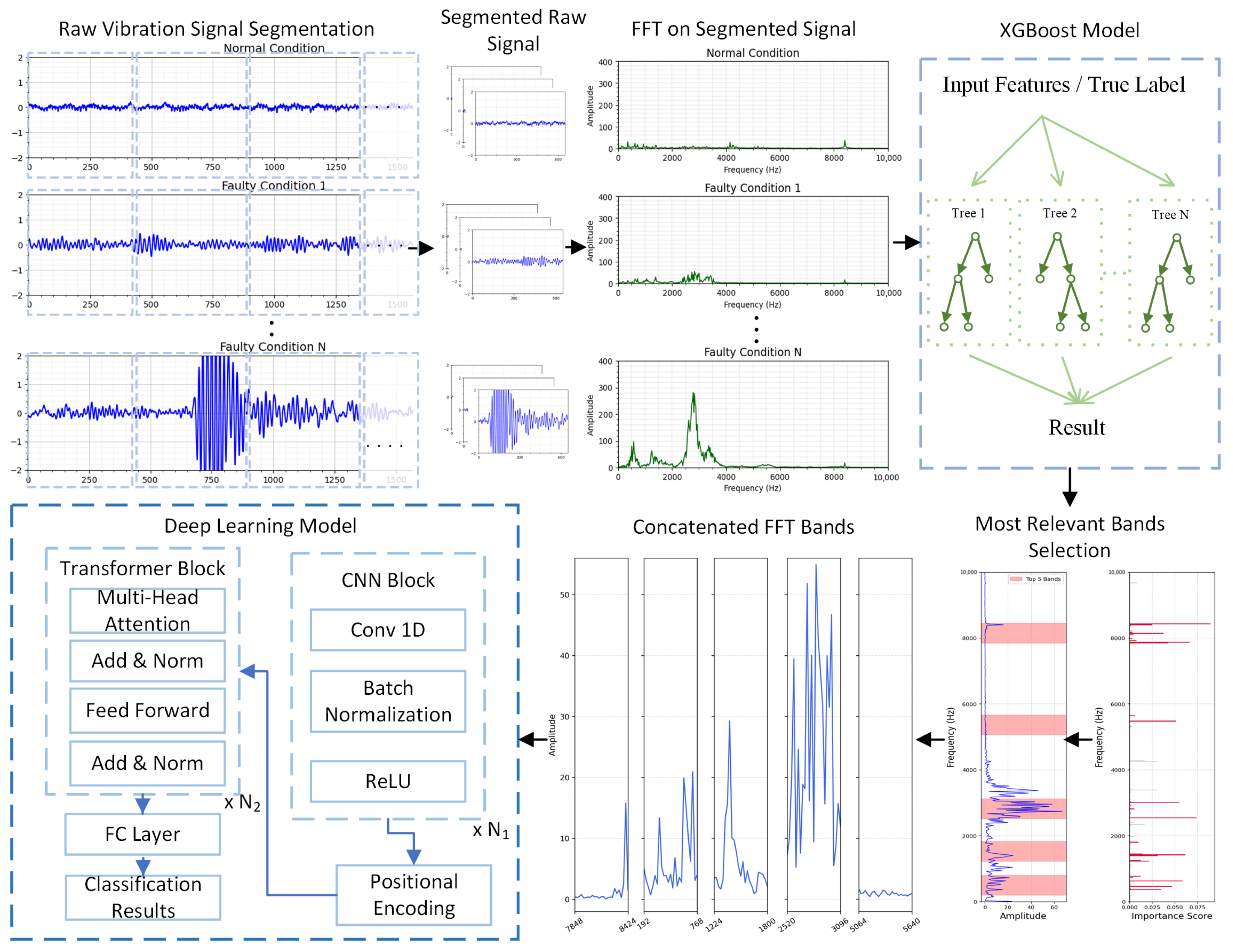

The primary contribution of this paper is the introduction of a novel vibration-based fault classification framework, which integrates interpretable spectral analysis and XGBoost-based frequency band selection, following with a CNN–Transformer hybrid model for efficient and accurate fault recognition. In addition, the proposed method introduces two key innovations that differentiate it from existing hybrid frequency band selection and deep learning approaches. First, the framework adopts a fully data-driven strategy to automatically identify the most discriminative frequency bands in the spectral domain, allowing the model to concentrate on the specific portions of the spectrum that contribute most to classification. This avoids the need for extensive manual feature engineering and enhances the interpretability of the selected frequency regions. Second, unlike previous studies that compute a large set of statistical features and then apply interpretable models for feature ranking, our approach directly applies XGBoost to the raw FFT magnitude spectrum to locate informative frequency bands. This direct frequency-domain selection preserves the physical meaning of the features, and avoids information loss from feature compression.

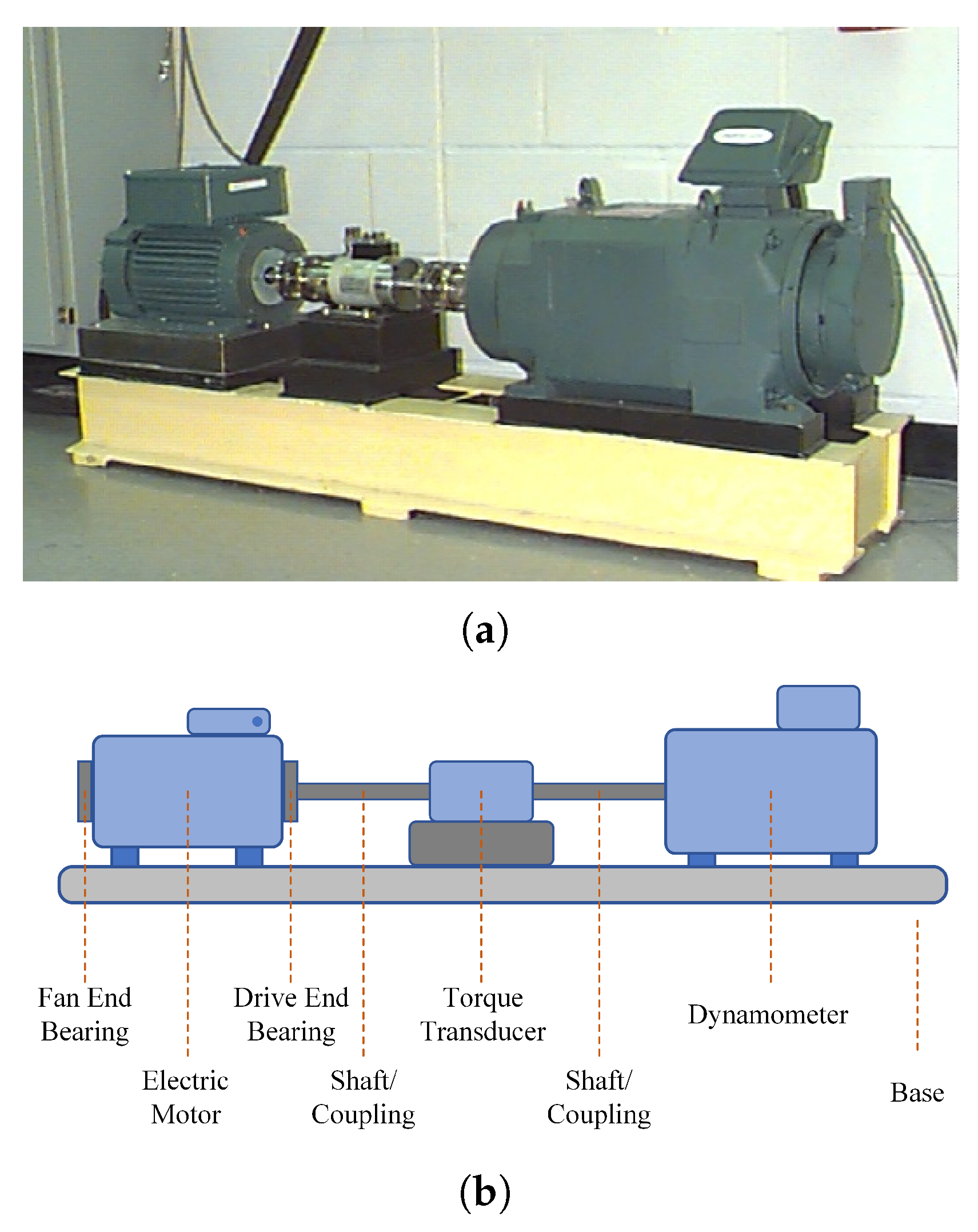

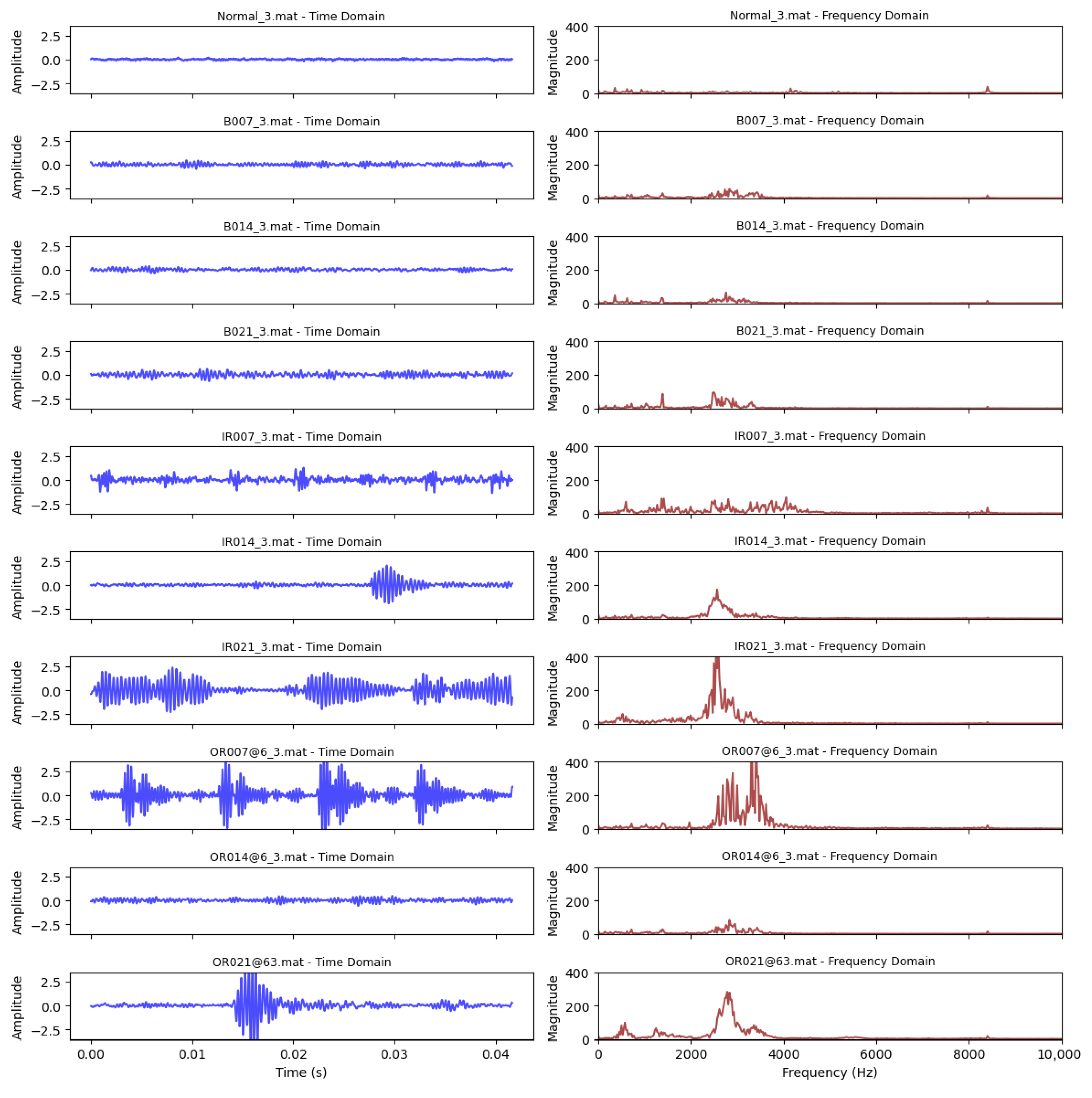

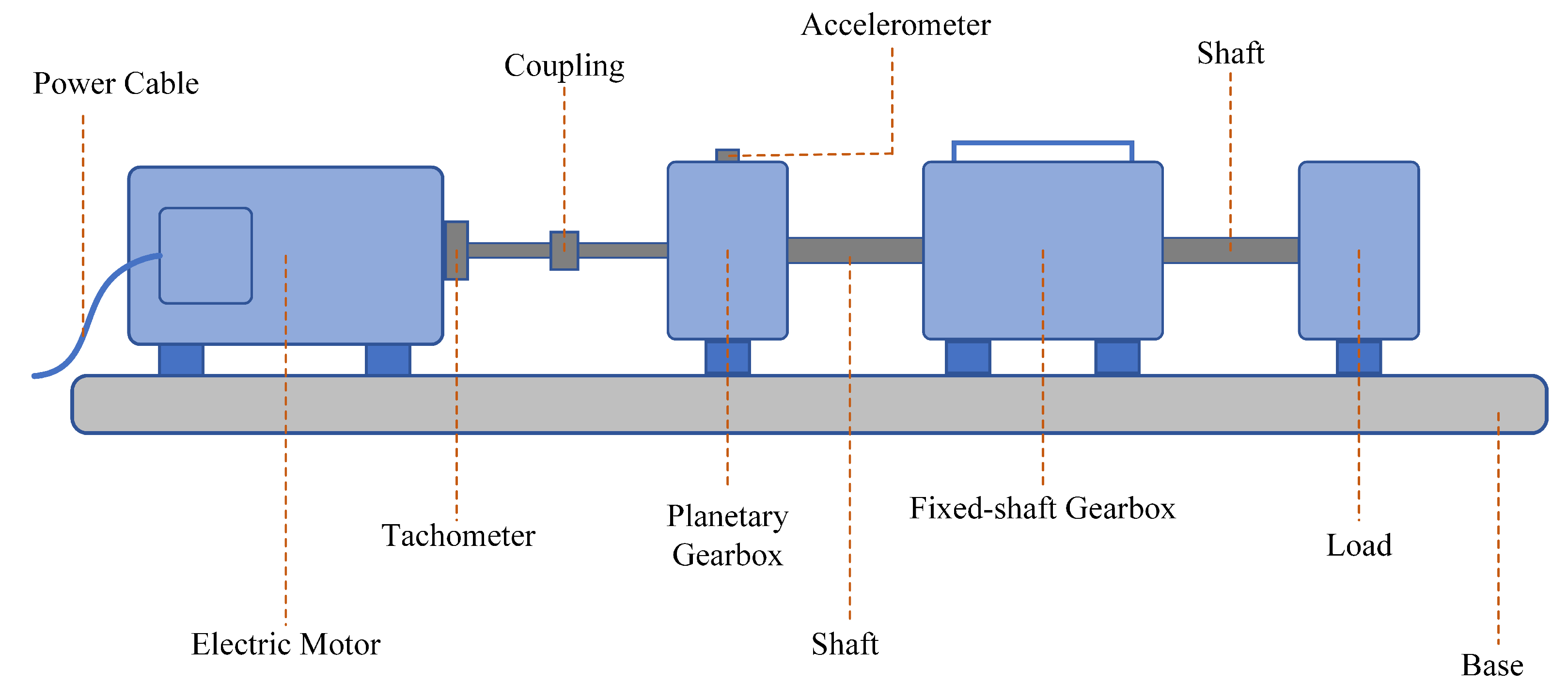

The capability of the proposed approach is examined using two well-established publicly available datasets, the Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) bearing dataset and the Beijing Jiaotong University (BJTU) planetary gearbox dataset, demonstrating its robustness across different fault types and mechanical systems. Furthermore, the proposed frequency band selection strategy significantly reduces the input feature dimensionality for deep learning model training, thereby improving computational efficiency without compromising classification performance.

The organisation of the remaining sections is as described below:

Section 2 depicts the proposed fault classification framework, covering the frequency band selection using XGBoost and the CNN–Transformer classifier;

Section 3 describes two open-access datasets used in this study.

Section 4 demonstrates and discusses the training results and performance analysis of proposed method on both datasets.

Section 5 summarises the findings, discusses the limitations of the proposed approach, and highlights potential improvements for further research.

4. Results and Discussion

During model training, the Cross-Entropy (CE) loss is adopted, as it is the standard objective for multi-class classification. It is defined as [

38]:

where

is the one-hot ground-truth label for class

c, and

is the softmax predicted probability of that class.

The classification accuracy is computed using the following equation, where

is the number of evaluated samples whose predicted class matches the actual label:

All experiments were conducted using the laboratory PC at the Centre for Efficiency and Performance Engineering (CEPE), University of Huddersfield. The system was equipped with an Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-14700 CPU (Intel, Santa Clara, CA, USA), 32 GB of RAM, and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060 GPU (NVIDIA, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The development environment was based on PyTorch version 2.5.1 and Python version 3.12.7. All model training tasks were accelerated using GPU computation via the CUDA toolkit (version 12.4). In this study, the same XGBoost model configuration was applied to both datasets for feature selection purposes. The model was trained using 100 decision trees for multi-class classification, during training, performance was evaluated using the multi-class logarithmic loss (log-loss) metric (Equation (

9)). The importance of individual frequency bands was calculated using the gain importance, which is defined in the Equation (

11).

For both datasets, the initial learning rate (LR) for each case was variable, and a LR decay factor of 0.90 was applied using a performance-based scheduling strategy. To ensure a sufficient number of samples for both training and evaluation, the full dataset was first split into a development set (80%) and an independent test set (20%) using stratified sampling. The development set was then further divided using 5-fold stratified cross-validation, where in each fold, four partitions were used for training and one for validation. During each fold, the model checkpoint that achieved the highest validation accuracy was retained and subsequently evaluated on the fixed 20% test set. The final results were reported as the mean and standard deviation of the test accuracy across the five folds. For each case, the model performance curves during training were plotted using the best fold model, and the confusion matrix was also generated using this best fold model on the independent testing dataset.

4.1. Training Results

4.1.1. Training Results on CWRU Bearing Dataset

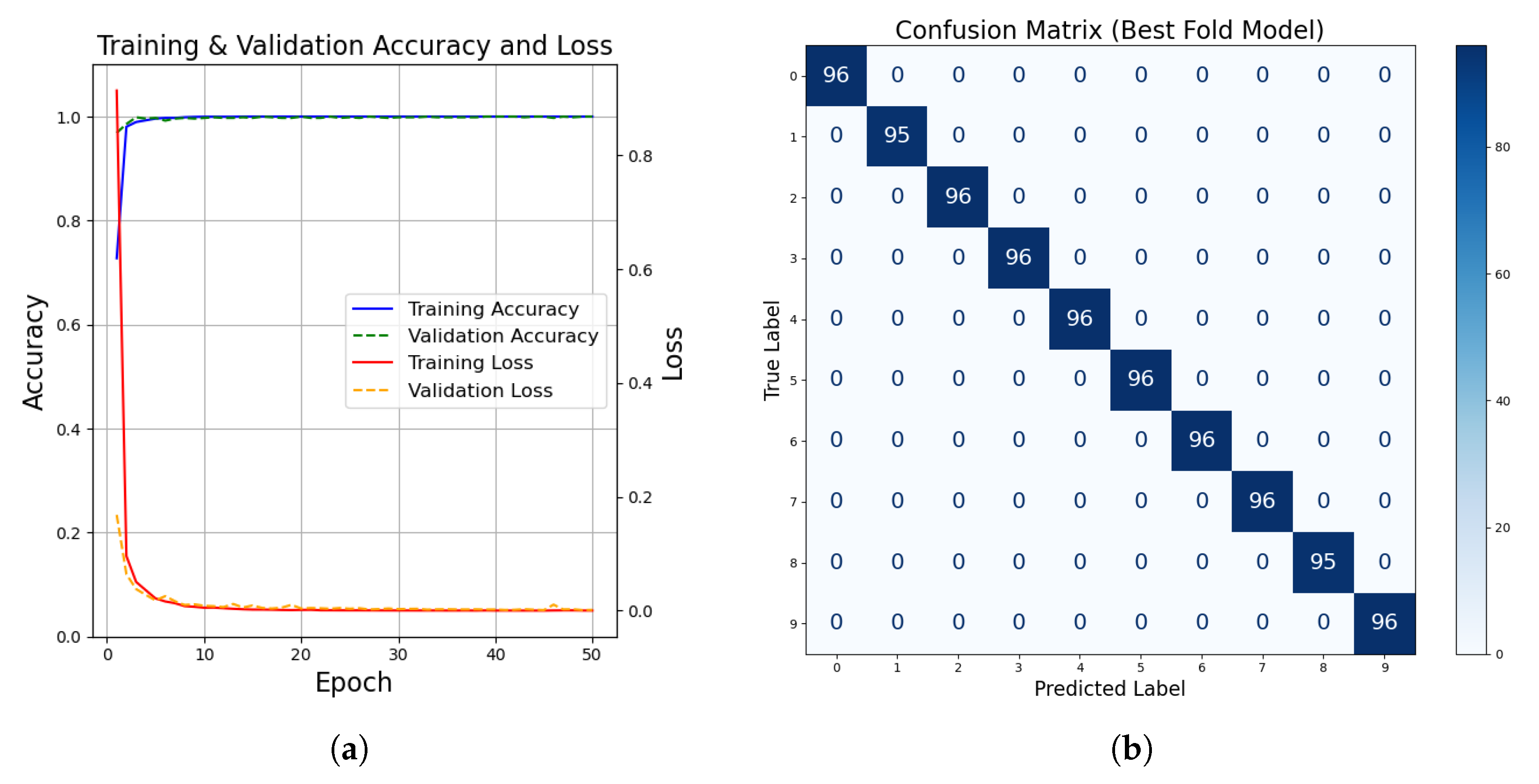

For the tests performed on the CWRU bearing dataset, the k-fold cross-validation strategy was adopted. This approach ensures that all samples in the development set are used for both training and validation across different folds, offers a more dependable assessment of of model performance, and mitigates the risk of bias arising from a single fixed train–validation split. The model architecture and hyperparameter settings for case 1 are shown in

Table 3.

Attributed to the proposed discriminative frequency band selection strategy, the model exhibited fast convergence during training. Therefore, the training process was carried out for a total of 50 epochs, with a fixed LR of 0.0008. The model architecture employed in this study, as illustrated in

Figure 1, includes one convolutional block and two transformer encoder layers. A single CNN block was used as the signals in the CWRU dataset present distinct vibration patterns that are easy to interpret.

The training and validation accuracy and loss curves as well as the corresponding confusion matrix are shown in the

Figure 6. The

Figure 6a demonstrates both classification accuracy and loss over 50 training epochs, the model exhibited rapid convergence within the first epochs, indicating the effectiveness of the proposed frequency band selection strategy. Both the training accuracy and validation accuracy stabilized above 99% after 10 epochs. Meanwhile, both the training and validation loss values decreased rapidly during early training and remained low throughout, indicating good convergence and minimal over-fitting.

Figure 6b shows the final classification results based on the confusion matrix of the best fold model on the independent test set. No misclassification occurred, indicating that the model successfully recognised every fault class. The mean classification accuracy across the five folds reached 99.94%, demonstrating highly reliable fault recognition performance. The detailed k-fold accuracy statistics over the independent testing dataset are summarised in

Table 4, which demonstrate the reliability and accuracy of the proposed method in diagnosing the health status of ball bearings.

4.1.2. Training Results on BJTU Wind Turbine Planetary Gearbox Dataset

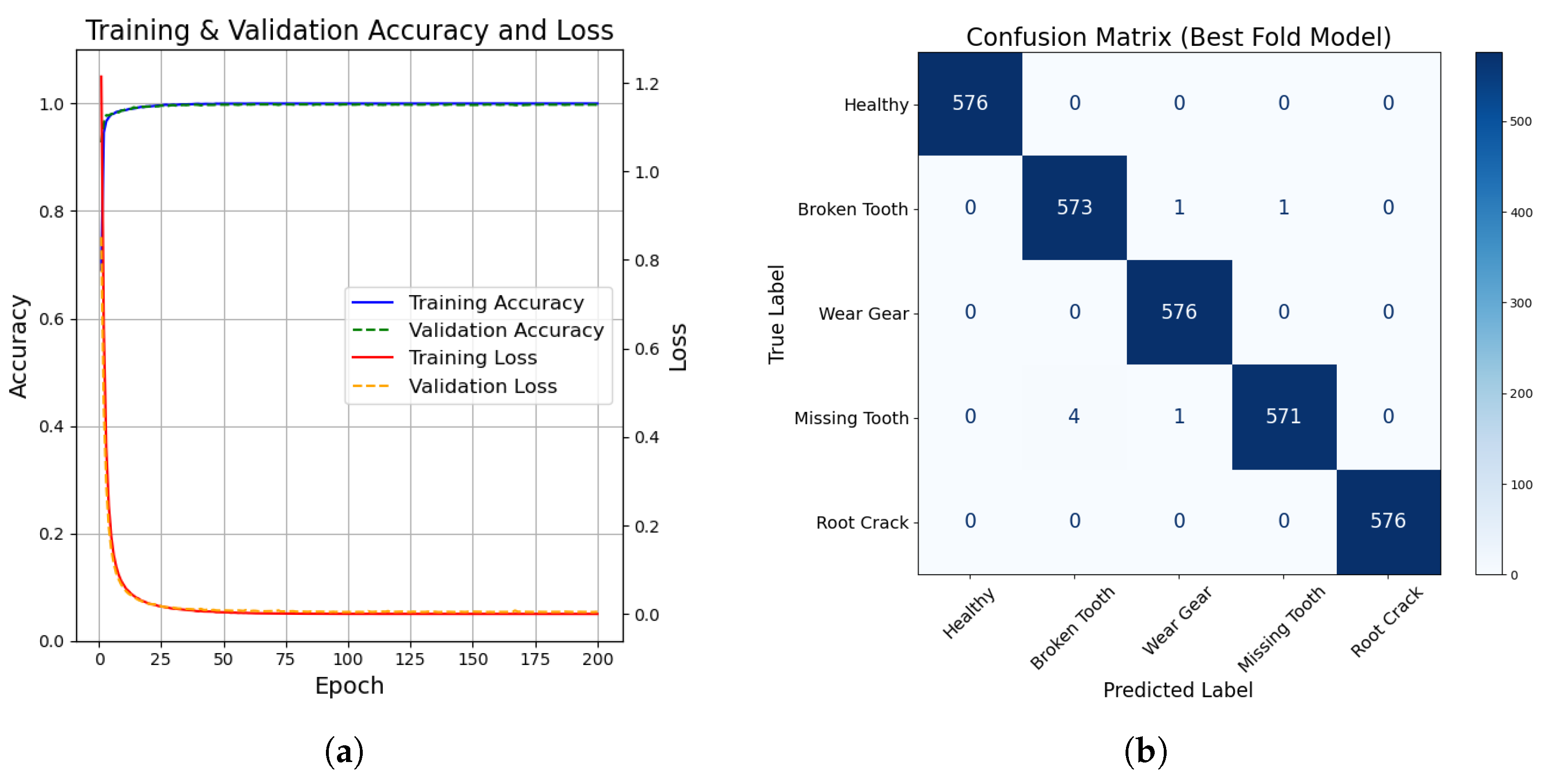

For the experiments conducted on the BJTU planetary gearbox dataset, the same cross-validation framework described earlier was applied to ensure robust and unbiased performance evaluation. This approach is also suitable for this dataset, which contains a large number of samples across multiple operating conditions, enabling reliable model optimisation while preventing any fixed split which might bias the evaluation. In this case, a total of 200 epochs was used during training, and the LR was initialized at 0.00002. As illustrated in

Figure 1, the model architecture consisted of two convolutional blocks and two transformer encoder layers. In this case, an additional CNN block was introduced to better capture the more complex vibration characteristics of the signals in the BJTU dataset. The model architecture and hyperparameter settings for case 1 are shown in

Table 5.

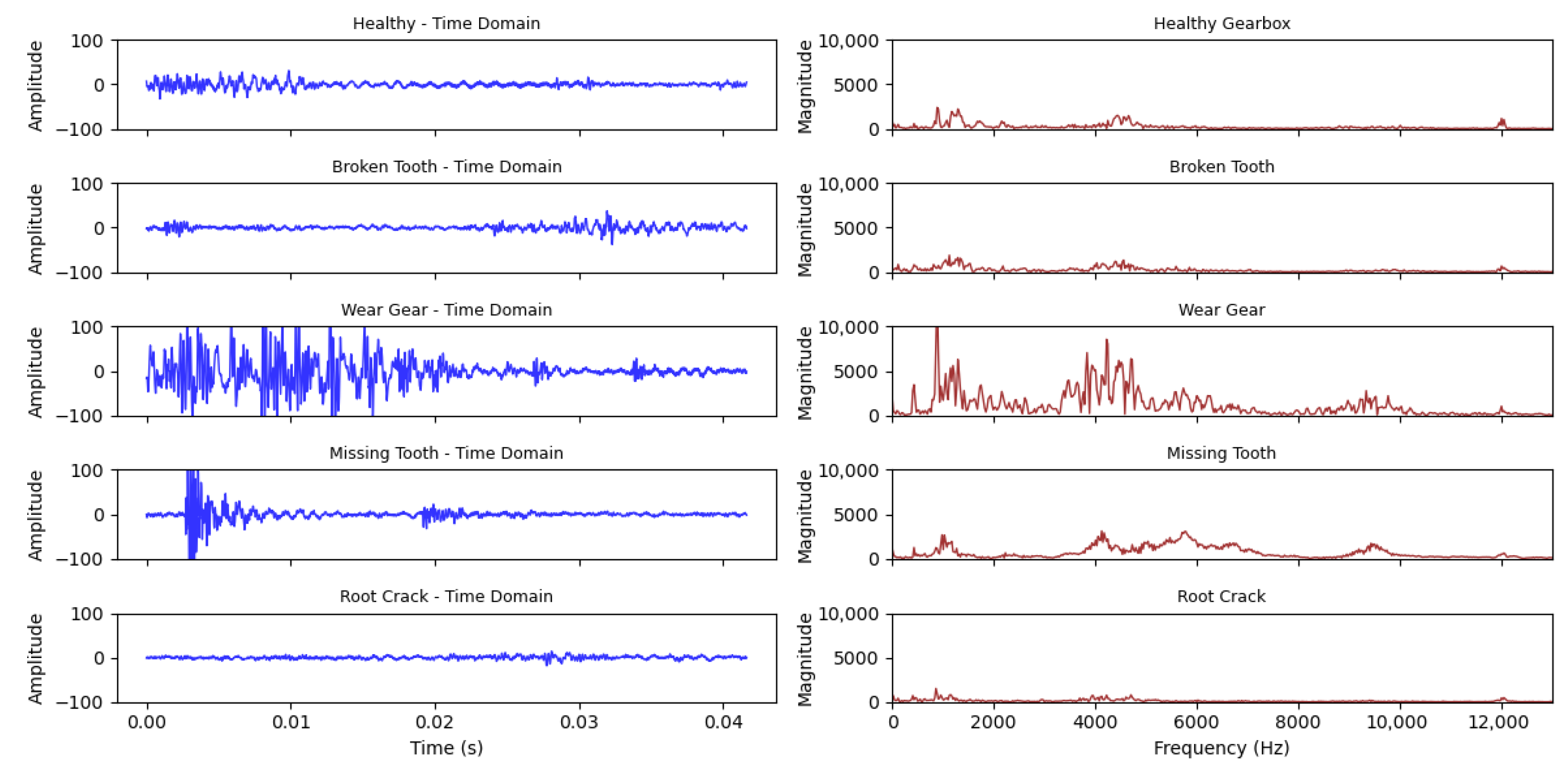

Figure 7 shows the performance curves and confusion matrix on case 2.

Figure 7a presents the training and validation curves for the BJTU planetary gearbox dataset over 200 epochs. In the figure, the model has demonstrated efficiency and stable convergence, with both training and validation accuracies reaching above 99% within the first 50 epochs. As training progressed, the loss continued to decrease smoothly, and no signs of over-fitting were observed. The corresponding confusion matrix is shown in

Figure 7b. As illustrated, the model demonstrated strong and reliable classification accuracy for all five fault classes. Only a few misclassification cases were observed, mainly between the ‘Broken Tooth’ and ‘Missing Tooth’ classes, while the remaining categories were classified correctly in all cases. The mean testing accuracy across the five folds reached 99.70%, further demonstrating that the proposed approach maintains high performance. The complete k-fold accuracy statistics over the independent testing dataset are summarised in

Table 6. From the results listed in the table, the outcomes suggest that the proposed method also performs very well in diagnosing planetary gearbox failures.

4.2. Performance Analysis

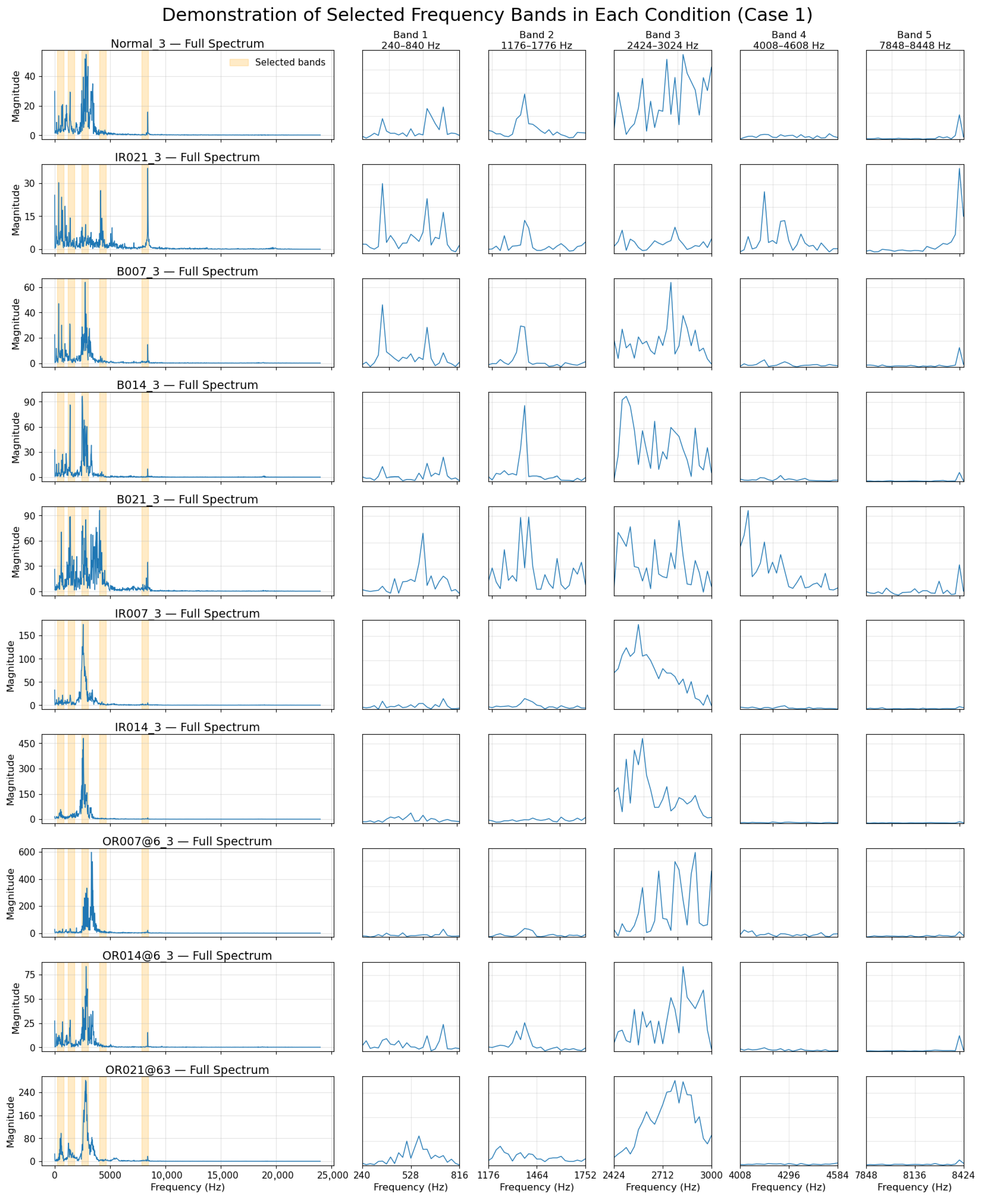

Table 7 and

Table 8 presents the ranked frequency bands selected for Case 1 and Case 2, respectively, based on importance scores obtained from the XGBoost feature selection algorithm.

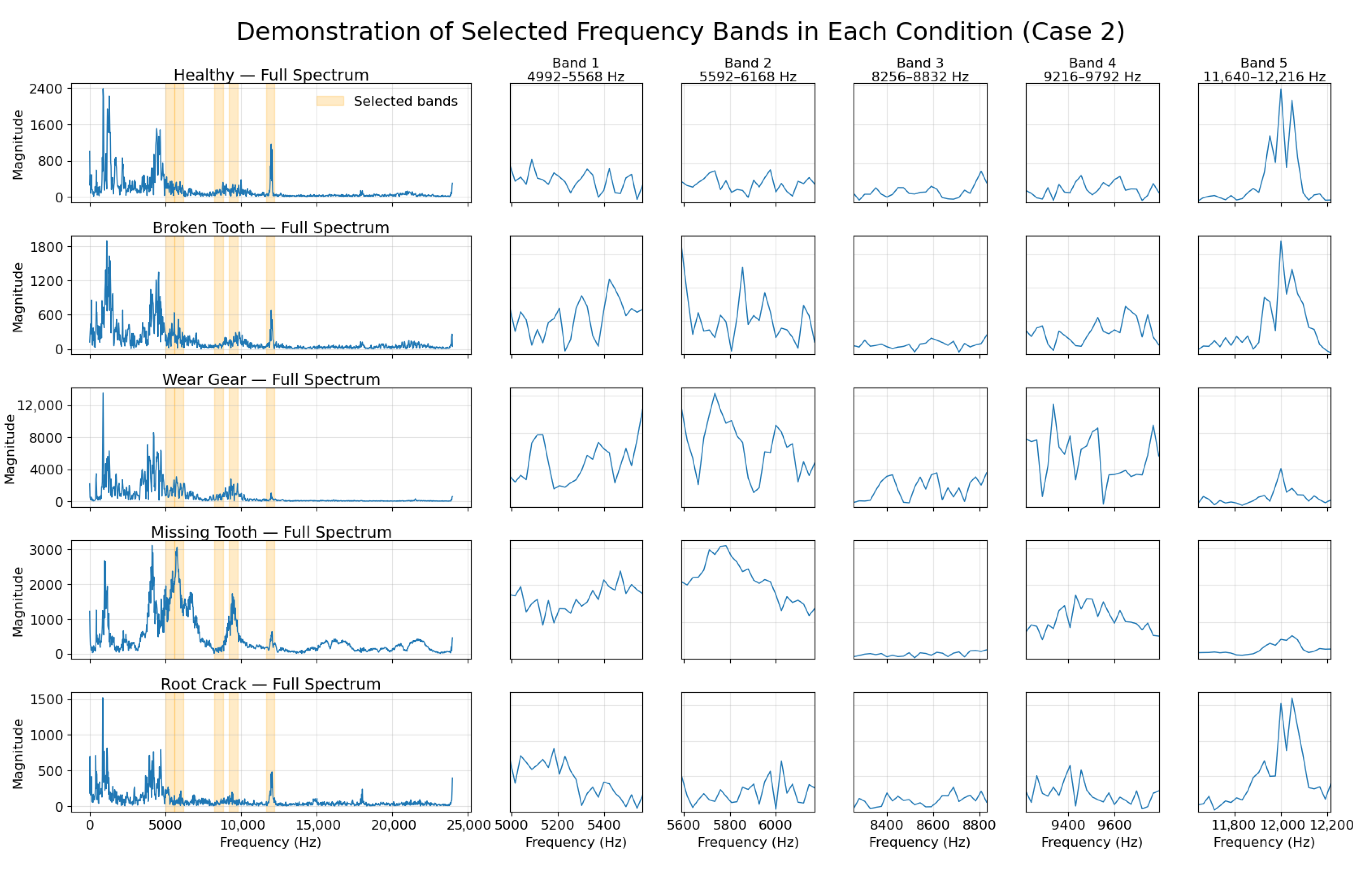

As discussed previously, the number of selected frequency bands was predefined to ensure coverage of at least 75% of the total spectral importance. In Case 1, the top five bands collectively account for more than 85% of the total importance, while in Case 2, the top five bands contribute over 75%. These results confirm that the choice of using the top five bands is sufficient to retain the majority of relevant frequency-domain information in both cases. It is noteworthy that the most informative frequency bands, specifically (

Figure 8), 7848–8448 Hz in Case 1 and 8256–8856 Hz in Case 2, do not coincide with the conventional fault characteristic frequencies. This finding suggests that manual frequency selection based solely on theoretical fault-related characteristic frequency calculations may fail to capture the most informative features present in real-world data for DL model training. In contrast, the data-driven selection approach employed here enables the identification of critical frequency bands that contribute directly to classification performance. The presence of the low-frequency band 240–840 Hz in Case 1 and the high-frequency band 11,640–12,240 Hz in Case 2 suggests that relevant diagnostic information is not confined to a specific spectral range and may vary depending on the machinery or fault scenario. This reinforces the strength of the proposed XGBoost-based band selection strategy, which identifies informative frequency bands through data-driven analysis rather than relying on artificially defined fault-related frequencies.

As discussed in the

Section 2.2, the individual frequency bin importance scores were extracted using gain-based importance from the trained XGBoost classifier. After obtaining the gain score for each frequency bin, a sliding window approach with a stride of one bin was applied to aggregate the importance scores across contiguous frequency bands. To ensure non-overlapping selection, bands were iteratively selected by excluding any frequency band that overlapped with previously chosen ones. This process continued until the predefined number of most discriminative frequency bands was identified. The selected frequency bands are shown in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9.

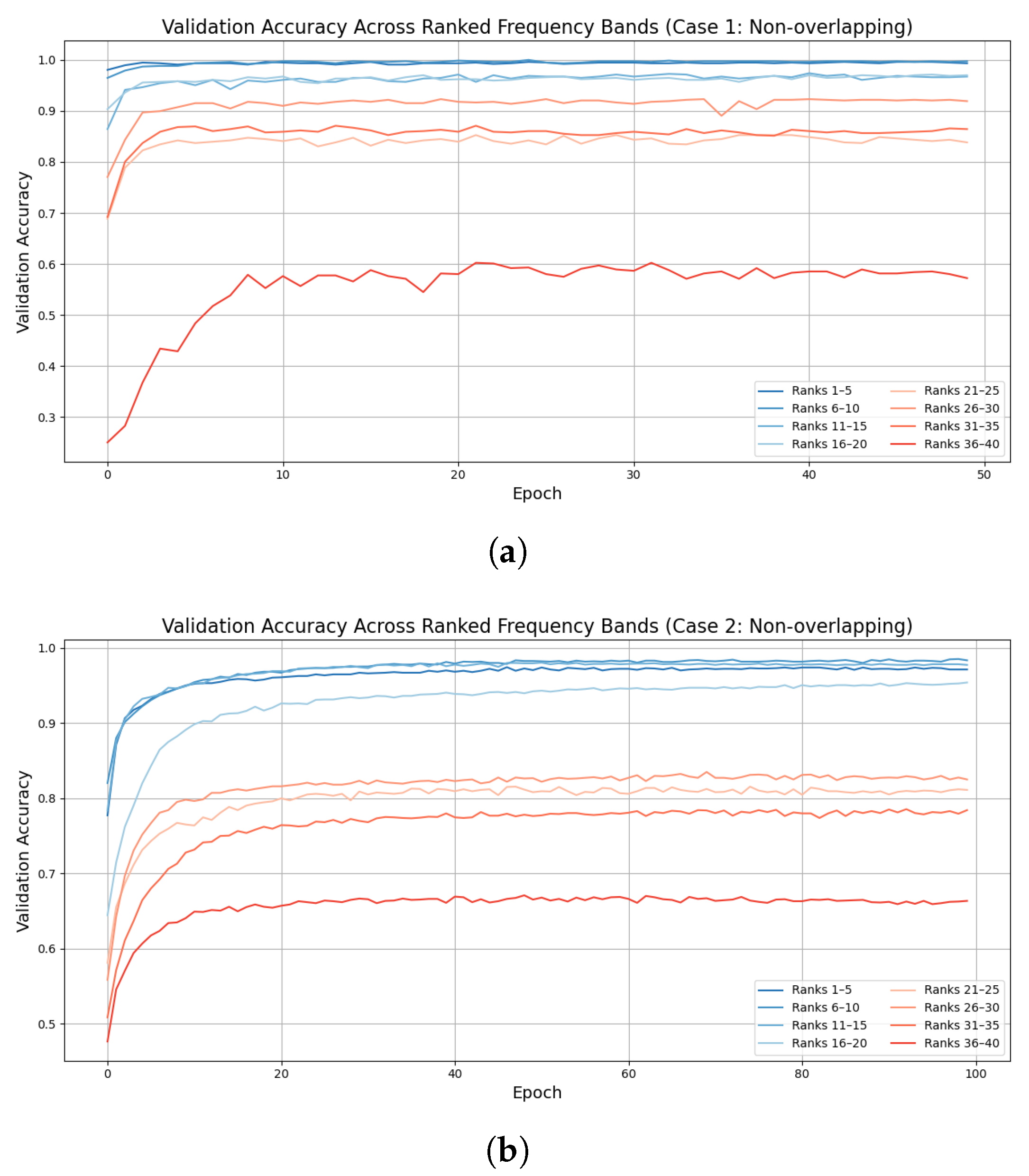

To visualize the effect of using frequency bands with varying importance levels and to simplify computation, the sliding window technique was modified to use non-overlapping windows instead of a stride of one bin. This resulted in 40 non-overlapping frequency bands across the entire frequency spectrum. These bands were ranked in descending order of importance and then divided into 8 groups based on their ranked position. The model was trained 8 times, each time using one group of frequency bands as input features, and the validation accuracy results for each group are presented in

Figure 10. In both cases, it can be observed that groups containing the highest ranked frequency bands (specifically ranks 1–5 and 6–10) achieved substantially higher validation accuracy. This result demonstrates that in both scenarios, the top five most relevant bands are sufficient to achieve high classification performance while maintaining computational efficiency. On the other hand, as lower ranked frequency bands were used, the model performance gradually degraded. This trend indicates that a limited number of selected frequency bands can preserve most of the information needed for DL models, leading to efficient input reduction while maintaining high performance. The results also reinforce the validity of the proposed band selection strategy across different rotating machineries.

To further demonstrate the superior fault detection performance of the proposed method over existing machine learning approaches, a comparison with state-of-the-art machine learning-based fault detection techniques was conducted in the study. A summary of these techniques is presented in

Table 9, highlighting their feature extraction strategies, model architectures, and reported classification accuracies. Among these techniques, an advanced Transformer model proposed in [

42] that uses frequency features and a multi-scale encoder to capture both local and global fault patterns. With a custom cross-flipped decoder, the model achieved 99.85% accuracy. The method proposed in [

43] combines wavelet packet decomposition with a DBN classifier, where DBN hyper-parameters are optimized using a chaotic sparrow search algorithm. Among these techniques, the method presented in [

44] transforms vibration signals into time–frequency representations through variational mode decomposition and continuous wavelet transform, which are then classified through an improved CNN. This image-based approach enables spatial feature learning and achieves strong diagnostic performance across varying operating conditions. The approach described in [

45] introduces a time-domain diagnosis model based on the KACSEN architecture, which leverages the Kolmogorov–Arnold framework for complex feature mapping. By integrating an attention mechanism, the model emphasizes informative signal components and performs effectively under different fault types. In [

46], an end-to-end fault diagnosis framework combining a multi-scale CNN with LSTM layers is proposed, where the CNN extracts hierarchical features from both raw and down-sampled time-domain signals, and the LSTM captures temporal dependencies for final classification. Compared with these existing methods, the proposed model demonstrates strong performance in terms of accuracy, efficiency, and interpretability. Unlike approaches that depend on signal pre-processing, manual frequency localization, image conversion, or complex in-model computations, our method directly utilizes selected frequency bands. In our experiments, only 1/8 of the total frequency bands were selected and used for model training, significantly reducing the input size without compromising performance. The application of XGBoost for band selection ensures that only the most informative spectral regions are retained, effectively minimizing redundancy. Combined with a hybrid CNN–Transformer architecture, the model captures both local and global signal patterns with high effectiveness.

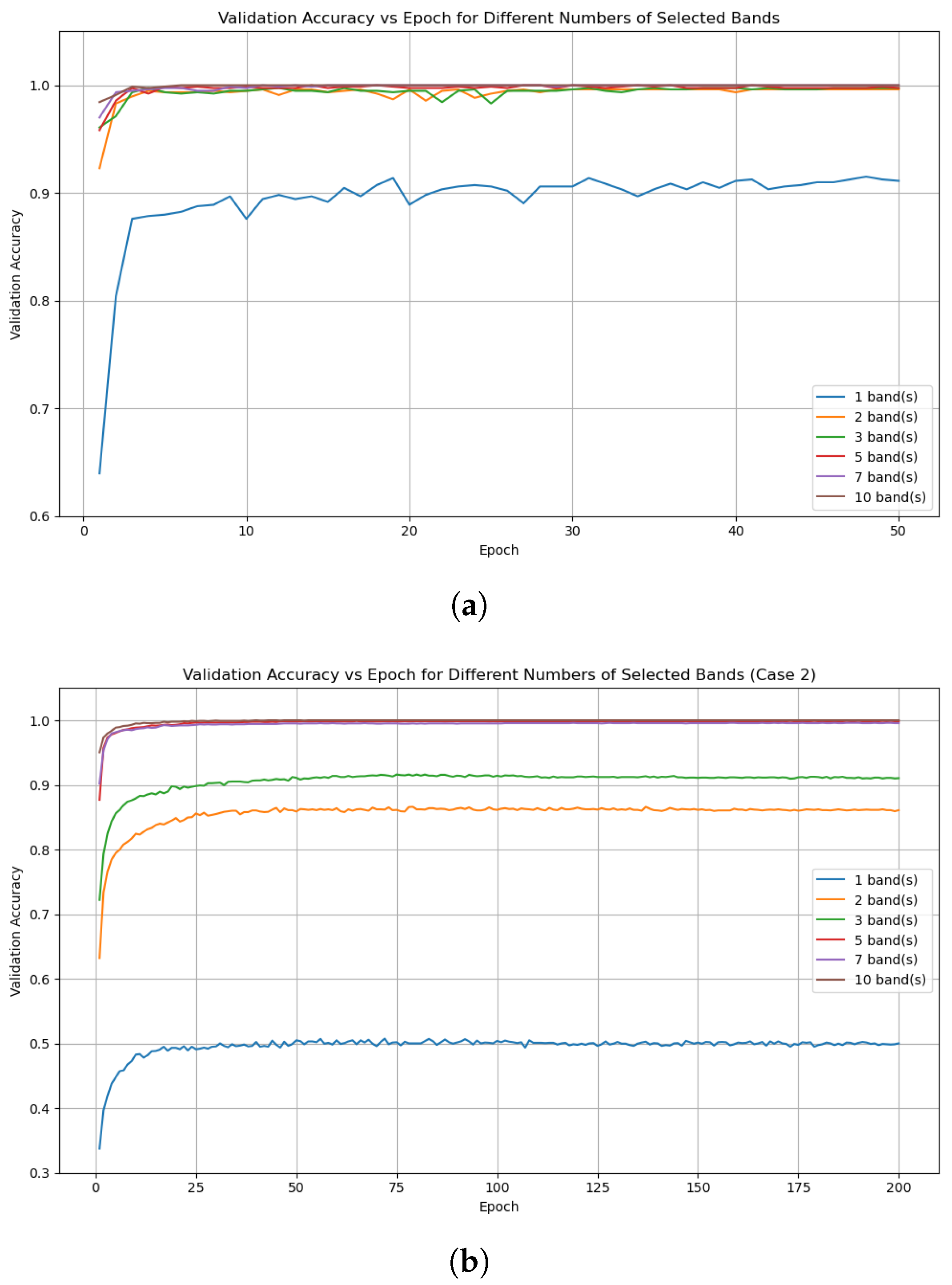

Because the number of selected frequency bands can directly influence the performance of the proposed method, the study includes an additional set of experiments to examine how different quantities of ranked bands affect the downstream model. After computing the gain-based FFT-bin importance using XGBoost and forming non-overlapping ranked frequency bands, several band-selection configurations were constructed by taking the top 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, and 10 bands. These configurations cover a wide range of cumulative importance, from very small proportions (25%) of the total bin-level importance to more than 90%. For each configuration, the corresponding FFT bins were used to generate a reduced feature set. All other components of the workflow, including the data-splitting strategy, k-fold cross-validation procedure, model architecture, and hyperparameter settings, were kept identical to those used in the main experiments.

The classification results obtained under different band-selection settings for Case 1 are summarised in

Table 10 and

Figure 11a. When only one or two frequency bands are selected, the mean classification accuracy remains noticeably lower than the accuracy achieved using larger numbers of bands. This shows that the spectral information contained within one or two isolated bands is insufficient to represent the vibration patterns required for reliable fault detection. In contrast, when three or more frequency bands are selected, the classification accuracy reaches a consistently high level across all five folds. The results for 3, 5, 7, and 10 bands are almost same, reflecting the fact that the classifier already achieves near-saturation performance once a sufficient amount of informative spectral content is included.

Although the performance obtained using three bands is already high, five bands were adopted in the study because they retain a larger cumulative importance fraction and provide broader spectral coverage while keeping the dimensionality low. This choice offers a more reliable balance between information content and feature compactness, ensuring stable performance without introducing too many unnecessary complexities.

The results for Case 2, shown in

Table 11 and

Figure 11b, follow a similar pattern to Case 1. Using only one band leads to low accuracy, while increasing the number of selected bands quickly improves performance. With three bands, the mean accuracy rises sharply to above 0.91, and once five or more bands are used, the accuracy becomes consistently high across all folds.

Once 5 bands are selected, the accuracy becomes highly consistent across all folds, and the results for 5, 7, and 10 bands are almost same. This shows that the classifier reaches its performance ceiling once a sufficient portion of discriminative spectral content is included, and adding further bands does not provide any significant improvement. Although using ten bands yields a very slightly higher accuracy than using five bands, this comes at the cost of doubling the number of input features while offering no practical benefit. These observations confirm that setting the number of frequency bands to five is an appropriate and well-balanced choice for the study.

To evaluate the contribution of different architectural components and input representations, several baseline models were implemented and compared directly against the proposed CNN–Transformer method. The baseline configurations include a CNN-only model, a Transformer-only model, and a CNN with lightweight attention, each tested using both time-domain input and full frequency-domain input without band selection. All models were trained using the same settings and k-fold cross-validation to ensure a consistent comparison.

Table 12 summarises the results. The models using time domain features show limited accuracy, indicating that raw vibration signals are difficult to classify without transformation. Accuracy increases substantially when full FFT spectra are used, confirming the advantage of frequency-domain features. Notably, the proposed method achieves accuracy comparable to the full spectrum frequency domain models while using only one-eighth of the data, due to the XGBoost-guided selection of the most informative frequency bands. This demonstrates that the proposed band-selection strategy preserves the essential discriminative information while significantly reducing the input dimensionality, and that the CNN–Transformer architecture effectively leverages these compact spectral features.

5. Concluding Remarks

This study proposed a frequency-domain fault classification framework that integrates FFT-based feature extraction, data-driven discriminative frequency band selection, and a CNN–Transformer hybrid model for classification. Feature extraction was carried out by applying the FFT to segmented sets of raw vibration signals. The obtained frequency spectra were then divided into multiple frequency bands, and XGBoost was employed to evaluate and rank the importance of each frequency band based on its contribution to classification accuracy. The top-ranked frequency bands were regarded as the most discriminative bands and subsequently fed into the hybrid DL model for fault classification.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed framework, a series of experiments were conducted on two open datasets: the CWRU bearing dataset and the BJTU planetary gearbox dataset. Experimental results show that the CNN–Transformer classifier, utilizing the identified discriminative frequency bands, consistently outperforms the approaches in the existing literature by achieving superior classification accuracy across diverse fault types and mechanical systems. This confirms that the combination of data-driven discriminative frequency band selection and DL holds strong potential for robust and efficient fault diagnosis.

In the present study, the method was evaluated using datasets collected under stationary rotational speeds, as the initial objective was to assess its feasibility under controlled conditions. However, the proposed method is also applicable to wind turbine non-stationary condition monitoring signals because wind turbines operate at very low rotational frequencies (<0.3 Hz), exhibit minor speed fluctuations in a short time, and are typically monitored using high sampling frequencies in the practice of drive train condition-monitoring (typically 20 kHz; the dataset used in this study was sampled at 48 kHz). Moreover, the XGBoost-based discriminative frequency band identification approach can be applied not only to frequency spectra but also to time–frequency representations obtained through techniques such as Continuous Wavelet Transform, Short-Time Fourier Transform, and Hilbert–Huang Transform, which are widely used for non-stationary signal analysis. Therefore, the approach presented in this paper can be further enhanced in future work through the incorporation of these advanced signal-processing methods.

Furthermore, the current frequency band identification method is restricted to one-dimensional features derived solely from the frequency spectra of vibration signals. Future work may explore extensions of this framework by incorporating higher-dimensional inputs, such as time–frequency representations, or by investigating multi-channel and feature-fusion techniques. These directions could enable the model to capture more complex temporal and spatial patterns, thereby enhancing its generalizability to real-world fault scenarios.