1. Introduction and Purpose

Bridge infrastructure is a critical component of transportation networks that support the transit of people, goods and services. Bridges also play an important role in reducing the cost of transport, improving accessibility, and enabling trade and commerce between regions [

1]. Bridges deteriorate as a result of both loads and time, with the former including those due to various types of vehicles; the latter includes but is not limited to the effects of material aging and environmental conditions such as variations in weather [

2]. Heavy traffic, especially freight traffic, places constant loading on structural elements resulting in capacity reduction due to fatigue and damage accumulation [

3]. Environmental conditions such as temperature fluctuations, moisture ingress and chemical agents (e.g., the use of deicing salts), all cause deterioration of bridge materials in particular concrete and steel [

4]. For example, moisture containing chloride ions from deicing salts accelerates steel reinforcing corrosion, while freeze–thaw cycles are responsible for surface cracking and spalling of concrete [

4]. In this manner, it impacts the structural integrity of bridges and underlines the necessity for routine maintenance of safety and prevention of catastrophic failures.

Traditionally, bridge maintenance planning has been based on a mix of periodic inspections and expert opinion as well as schedules defined by bridge age or amount of traffic load. Due to the limitations, there is a growing trend in bridge maintenance towards data-driven approaches, especially machine learning (ML) techniques for predictive modeling of bridge deterioration. The ability of ML to analyze large amounts of historical data (e.g., inspection records, structural parameters and traffic loads) allows to find patterns and trends that are not easily observable in a manual inspection [

5]. The growing availability of data from smart sensors, remote sensing technologies and infrastructure monitoring systems further promoted the application of ML in bridge management [

6]. Despite substantial progress in developing ML models to predict bridge deterioration, a lack of understanding regarding the effect of environmental conditions on the rate of deterioration means that there is still an important gap remaining.

Most ML models today in bridge maintenance work on structural parameters and inspection data while treating environmental factors either as a secondary consideration or they are indeed left out of the model completely [

2,

5,

7]. This method’s lack of generalizability limits its application to structures like bridges in regions with intense or diverse climates. Moreover, adverse effects of climate change will most likely increase the environmental loads on bridges; hence, such conditions should be factored into predictive models [

8]. Due to the increasing focus on data-driven decision-making in infrastructure management, it is crucial to improve ML models so they can learn from environmental data more effectively. This will give a comprehensive view of the factors leading to the deterioration of bridges resulting into an integrated prediction and reliable maintenance stratagem. This integration will not only enhance the reliability of predictions over diverse climatic regions but also allow one to develop region-specific maintenance protocols addressing both structural and environmental vulnerabilities.

This study addresses these gaps by integrating environmental variables with structural and inspection data into ML-based predictive models for bridge deterioration. Unlike prior studies that primarily relied on structural and inspection data, the innovation of this study lies in the explicit integration of environmental stressors such as freeze–thaw cycles, precipitation, humidity, condensation risk, and temperature extremes into machine learning models of bridge deterioration. This integration, coupled with the use of advanced resampling techniques to address severe class imbalance and a multi-metric evaluation framework, allows for the development of climate-aware predictive models that are more generalizable across regions and resilient to changing environmental conditions. The research focuses on the National Highway System bridges in Colorado, leveraging 11 years of historical data from the National Bridge Inventory (NBI) and climate records from the PRISM dataset.

3. Materials and Methods

Data for this research was collected from two main sources. The bridge data used for analysis were downloaded from the NBI databases. The NBI provides data on condition ratings of bridge components. It categorizes them into a scale of 0–9, where 9 means “excellent” and 0 means “failed”. It includes data on design characteristics of the bridge and other operational characteristics, such as ADT. In addition, the database provides data on the states (good, fair and poor) of the bridge elements. Environmental data were collected from the PRISM dataset in respect to the state of Colorado. It includes temperature variables of maximum, minimum, and mean, precipitation and relative humidity. Because both the NBI and climate datasets follow standardized formats, the framework can be readily extended to other regions by linking local bridge inspection records with corresponding environmental data.

The data preprocessing stage consists of two main phases: (1) data cleaning and preparation, and (2) data standardization and transformation. In order to merge datasets, identifiers such as bridge id, and geographic coordinates (latitude and longitude) were used to align datasets. Due to varying changes in environmental data for a particular location, geographic proximity was important to ensure that climate data corresponded to the exact or nearest location of bridges considered. Also, environmental data such as temperature and precipitation are often recorded at daily or hourly intervals, therefore these data needed to be synchronized with the timeline of our structural data (such as bridge age). All preprocessing steps were validated by examining distributions of key variables (e.g., sufficiency rating, traffic load) before and after imputation, outlier handling, and standardization. These checks confirmed that preprocessing improved data quality while preserving the underlying distributional characteristics across all 97 features. A clean dataset was subsequently created containing information about bridges and environmental condition data from the NBI as well as the PRISM datasets, respectively. During the cleaning process, missing data and inconsistencies such as missing data related to condition ratings were identified. These inconsistencies affect the analysis of the data and hence are addressed by handling missing data, removing duplicate records, detecting outliers that can skew the model’s understanding of the data, and treating outliers. The integration of bridge structural data with environmental conditions required a systematic approach to data standardization and transformation. The NBI condition ratings, ranging from 0 to 9, were standardized alongside diverse environmental measurements to ensure computational compatibility and meaningful analysis. Class imbalance was addressed using the SMOTETomek algorithm, which combines oversampling of minority classes with undersampling of borderline majority samples. The SMOTETomek resampling method has been widely applied in civil infrastructure datasets to handle class imbalance while preserving neighborhood structure in high-dimensional feature spaces [

37]. For SMOTE, we set k = 5 nearest neighbors, ensuring that synthetic samples were generated within locally coherent neighborhoods in multi-dimensional feature space. Tomek Links were then applied to remove majority-class instances forming borderline pairs with minority samples, thereby improving class separability. Numerical features underwent standard scaling transformation, expressed as:

where Z represents the standardized value, x is the original value, μ is the feature mean, and σ is the standard deviation [

37]. This standardization was crucial for features such as bridge age, structure length, and traffic loads. To capture deterioration patterns effectively, a deterioration rate (

DR) was calculated for each bridge component:

where

CR represents the condition rating and

BA denotes bridge age adapted from. Environmental measurements required specific transformations, including temperature standardization to Celsius and precipitation to millimeters. The categorical variables were one-hot encoded, ordinal variables maintained their hierarchical relationships through appropriate encoding schemes, and missing values were handled through domain-specific methods. Environmental data gaps were filled using spatial interpolation from nearby stations, and structured measurements were replaced on a similar bridge attribute basis.

Feature selection was carried out using machine learning algorithms that are well suited for assessing variable importance. Decision Tree (DT), RF, and GB were employed to compute importance scores for each feature. A composite importance index was then derived by aggregating the results from all three models. Highly correlated features, defined as those with a correlation coefficient above 0.9, were removed to reduce redundancy. Predictors that consistently ranked highly across the models were retained as the most significant variables for deterioration prediction.

The predictive modeling framework was built on three machine learning algorithms: DT, RF, and GB (implemented via XGBoost). DT provided a baseline due to their interpretability, while Random Forests offered improved performance through ensemble learning and feature interaction handling [

48]. GB was selected for its strong predictive accuracy and robustness in handling class imbalance [

49]. SVMs were initially considered but excluded due to computational challenges with the large dataset, which contained over 75,000 samples and 97 features, further expanded through synthetic oversampling. Hyperparameter optimization for each algorithm was performed using GridSearchCV with stratified three-fold cross-validation. To address class imbalance, the SMOTETomek technique was applied, and model calibration was conducted using Platt scaling to produce reliable probability estimates:

where S represents the balanced dataset, X is the original feature set, N is the desired sampling ratio, and k is the number of nearest neighbors used in the SMOTE algorithm [

50].

The dataset was partitioned into training, validation, and test sets in a 64-16-20 ratio, stratified to preserve class distributions. Model-specific tuning included adjusting maximum depth, minimum samples per split, and Gini criterion for DT; selecting 100 estimators with bootstrap sampling for RF; and optimizing GB with a learning rate of 0.1, 100 estimators, and an early stopping criterion to prevent overfitting. To calibrate predicted probabilities, Platt scaling was applied by fitting a sigmoid function to decision scores on the validation set, which corrected for probability miscalibration commonly observed in imbalanced classification.

Model performance was evaluated using multiple metrics that are appropriate for class-imbalanced data. Balanced Accuracy, Cohen’s Kappa, MCC, and the Geometric Mean Score were employed alongside macro-averaged precision, recall, and F1-scores. Cohen’s Kappa coefficient metric is expressed as:

where po represents observed agreement and pe represents expected agreement by chance, providing a more robust measure of classification performance by accounting for random chance agreement [

37]. To specifically address class imbalance challenges, MCC metrics was implemented:

where FP represents false positives and FN represents false negatives [

51]. To ensure robustness, stratified k-fold cross-validation (k = 3) was used, and performance estimates were bootstrapped 1000 times to provide confidence intervals. These metrics offered a comprehensive evaluation of the models’ ability to predict bridge deterioration under realistic conditions. The same evaluation framework was applied to all three algorithms (DT, RF, and GB) to allow direct performance comparisons while mitigating issues related to the naturally imbalanced characteristics of infrastructure maintenance data. From a methodological standpoint, this study also made several design choices to ensure robustness and scalability. A correlation threshold of 0.9 was applied to reduce redundancy among predictors while retaining sufficient explanatory features, a level consistent with prior infrastructure deterioration studies [

39,

52]. In addition, Support Vector Machines were excluded after preliminary testing showed minimal performance gains (<0.5% difference in balanced accuracy) compared to tree-based models, while requiring substantially greater computation time on the full dataset. These choices ensured that the models remained both transparent and computationally feasible while maintaining high predictive performance.

4. Results

4.1. Dataset Overview

The dataset used in this study combined structural, operational, and environmental parameters for bridges located on the Colorado National Highway System between 2014 and 2024. After preprocessing, the merged dataset comprised 75,063 samples and 97 unique features, incorporating condition ratings for decks, superstructures, and substructures, along with traffic data, structural attributes, and climatic variables such as mean temperature, precipitation, relative humidity, freeze–thaw frequency, and condensation risk.

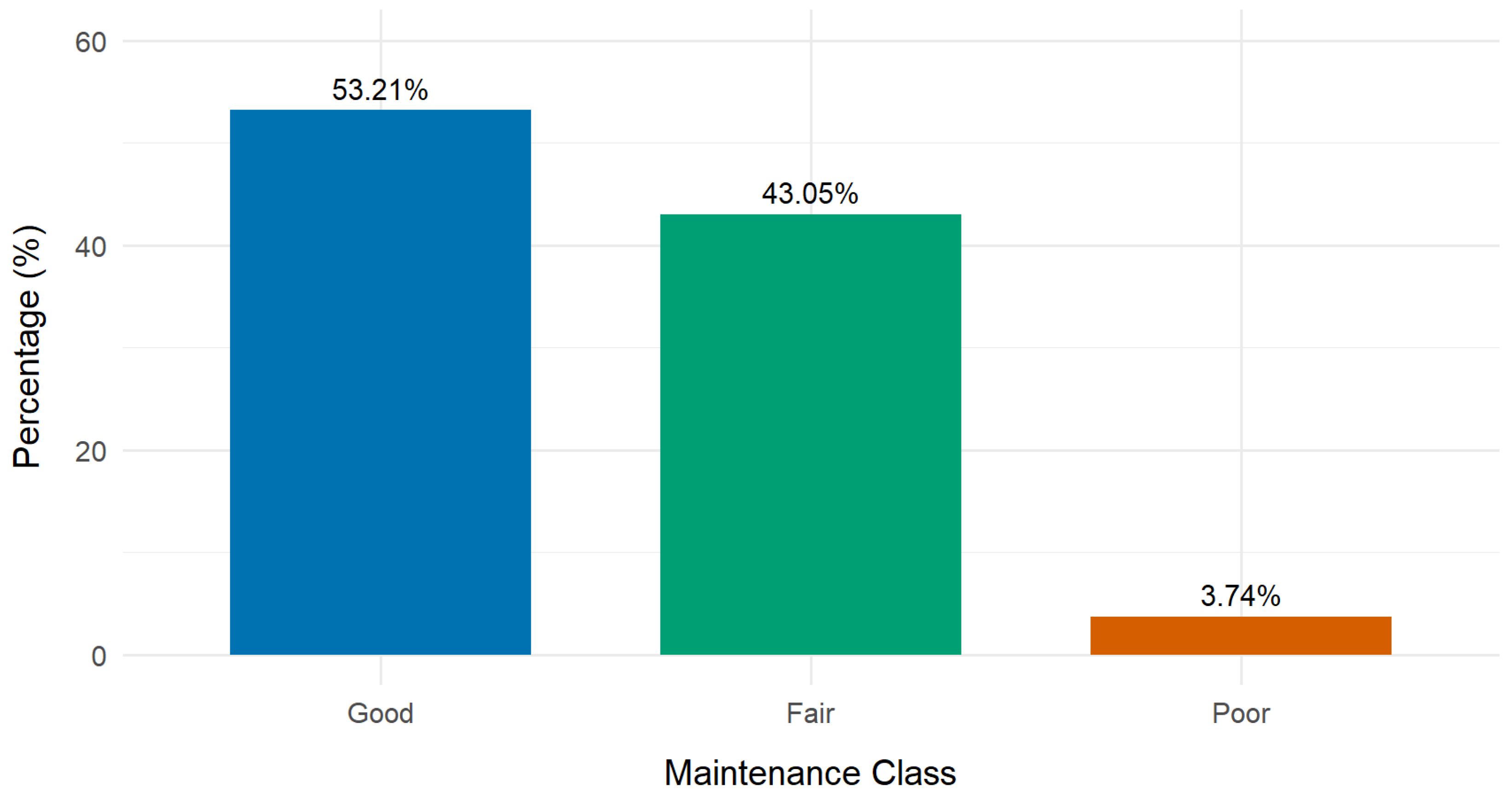

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of bridges across maintenance condition classes, showing that the majority of structures are in either “Good” (53.21%) or “Fair” (43.05%) condition, while only a small proportion fall into the “Poor” category (3.74%). This pronounced class imbalance necessitated the use of synthetic oversampling and undersampling techniques during model training, specifically SMOTETomek, to ensure that minority classes were adequately represented.

4.2. Feature Importance Analysis

Feature selection then cleaned the dataset by identifying useful predictors of bridge deterioration. Filtering at a high level of inter-feature correlation (threshold = 0.9) eliminated ten features, including ROADWAY_WIDTH_MT_051, BRIDGE_AGE, among others. Using DT, RF and GB classifiers to identify the most significant predictors of bridge deterioration feature selection was performed. Across all three models, the SUFFICIENCY_RATING emerged as the single most influential feature, with an average importance score of 0.6918, indicating its comprehensive representation of a bridge’s overall structural adequacy. Other prominent predictors included the year of construction (YEAR_BUILT_027), years since reconstruction, geographic coordinates (LAT_016, LONG_017), and approach roadway width (APPR_WIDTH_MT_051). Environmental factors, particularly freeze–thaw frequency, precipitation, and condensation risk, consistently ranked among the top contributors, highlighting the strong influence of climatic stressors on deterioration mechanisms [

53]. The top ten predictive features and their average importance scores are presented in

Table 1. The inclusion of geographic coordinates among leading predictors aligns with previous findings demonstrating the spatial variability of deterioration mechanisms driven by localized climatic and environmental conditions [

37].

Among the environmental variables included, freeze–thaw cycles and extreme temperature events consistently ranked among the most influential predictors across models. These stressors are well-documented drivers of cracking, delamination, and accelerated fatigue, particularly in deck elements. Precipitation and humidity also contributed measurably, with higher importance in substructure condition predictions, reflecting moisture-driven mechanisms of scour and material degradation. While chloride exposure was not directly represented in this dataset due to data limitations, related variables (e.g., freeze–thaw and precipitation) indirectly captured correlated effects. These results support the practical value of including climatic stressors in deterioration models, as they mirror known physical mechanisms of degradation.

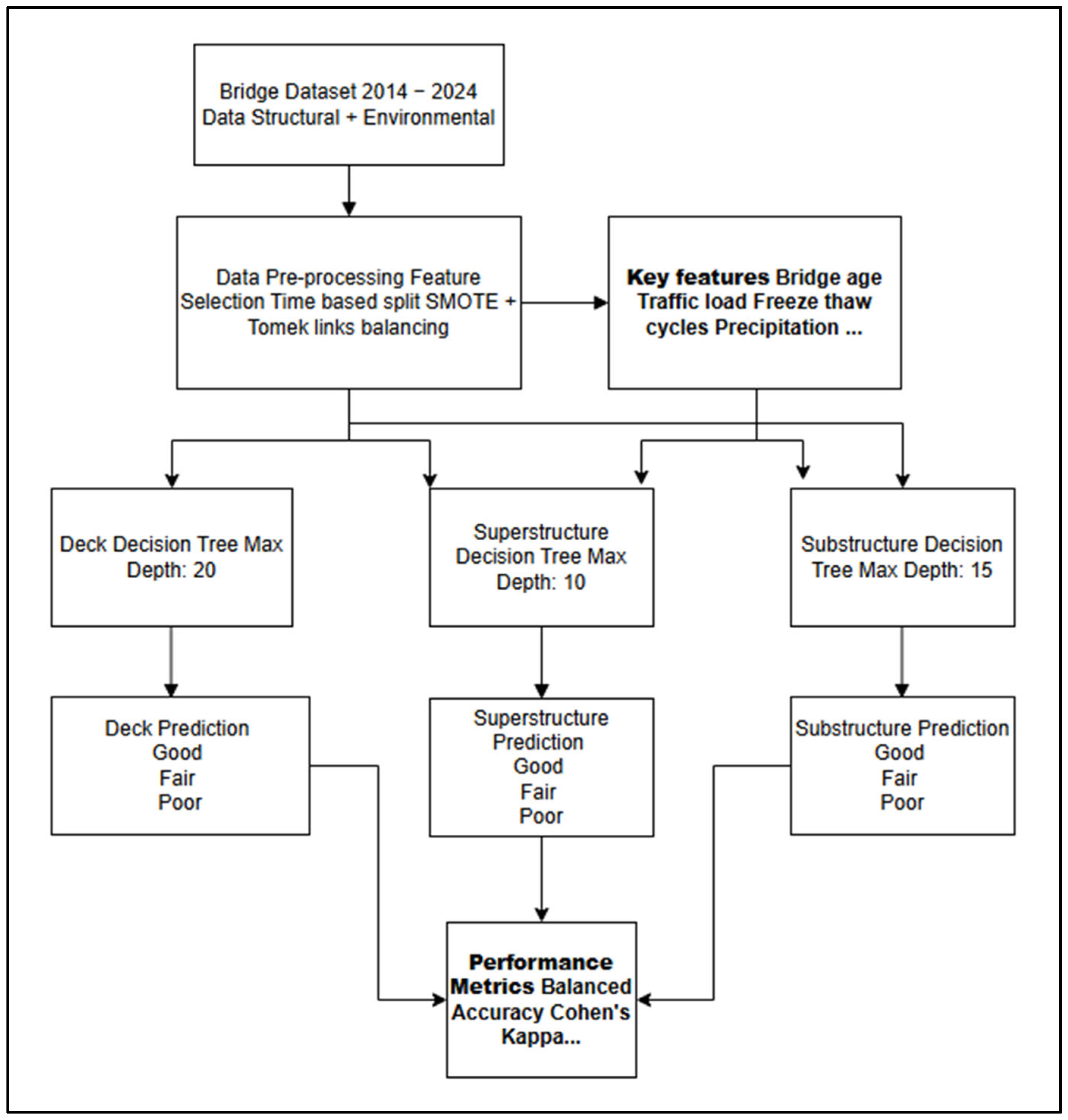

Figure 2 presents the DT-based modeling workflow applied for predicting deterioration states of bridge components. The model was developed to predict bridge maintenance needs, with key decision splits based on features such as bridge age, traffic load and freeze–thaw cycles. After preprocessing the dataset, feature selection was performed and the most significant predictors including bridge age, traffic load, freeze–thaw cycles, and precipitation were used to train component-specific DT for decks, superstructures, and substructures.

For Random Forest (RF), an ensemble of 100 decision trees was trained on bootstrap samples with replacement. At each split, a random subset of features (√p) was considered, which reduces correlation among trees and improves generalization. This configuration balances predictive stability with computational efficiency. The final prediction was determined by majority voting across all trees. For Gradient Boosting (GB), decision trees of maximum depth 3 were trained sequentially, where each tree was fit to the negative gradient of the loss function relative to current predictions. This process updates the ensemble in the steepest descent direction, incrementally improving predictive performance. A learning rate of 0.1 was used, and early stopping was applied (halting training after 50 rounds without improvement in validation loss) to ensure convergence and prevent overfitting.

Recent studies have reported comparable computational behavior for similar predictive tasks in bridge deterioration modeling. For instance, refs. [

39,

52] demonstrated that decision tree–based and ensemble methods achieve efficient convergence on multi-feature datasets with runtimes ranging from a few seconds to several minutes, depending on feature dimensionality and data volume. Ref. [

37]. achieved comparable processing times when optimizing gradient boosting for statewide bridge datasets, highlighting its suitability for large-scale monitoring. Likewise, refs. [

54,

55] noted that moderate increases in computation time are justified by tangible gains in predictive accuracy and decision support value for maintenance planning. These comparisons confirm that the models developed in this study fall well within the practical limits of computational efficiency reported in the recent literature while maintaining engineering applicability and scalability.

4.3. Model Performance Evaluation

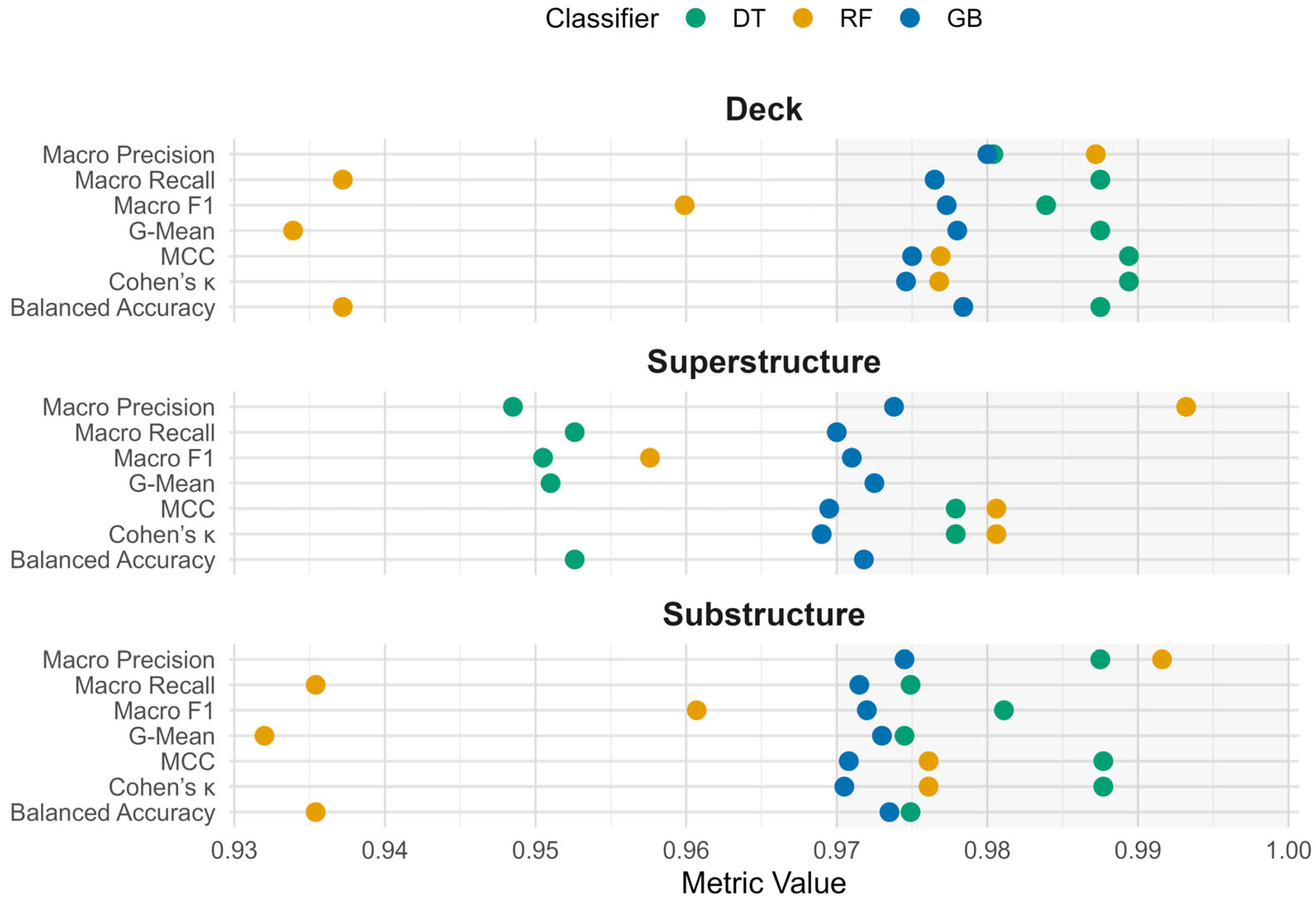

The predictive models were evaluated using balanced accuracy, Cohen’s Kappa, MCC, geometric mean, and macro-averaged precision, recall, and F1-scores. The results for DT, RF and RF classifiers are summarized in

Table 2.

Among the three algorithms, the GB classifier consistently achieved the best performance across all bridge components, with balanced accuracy scores ranging between 0.972 and 0.978 and MCC values near 0.97. DT, while slightly less robust overall, achieved the highest single metric for deck components, attaining a balanced accuracy of 0.9875.

Random Forests demonstrated stable and competitive results, though they generally trailed GB slightly in predictive performance. In addition to the numerical results presented in

Table 2,

Figure 3 provides a visual comparison of DT, RF, and GB across key metrics and components, highlighting relative strengths and performance stability of the models. These findings are consistent with prior studies [

38,

39] demonstrating the effectiveness of ensemble-based approaches such as GB and RF in modeling deterioration patterns of complex infrastructure systems.

Across components, the GB classifier consistently achieved the highest or near-highest scores across all evaluation metrics. For deck prediction, GB achieved a Balanced Accuracy of 0.978, compared to 0.988 for DT and 0.938 for RF. Although DT marginally exceeded GB in this single case, GB outperformed both DT and RF in superstructure prediction (0.972 vs. 0.953 for DT and 0.929 for RF) and substructure prediction (0.974 vs. 0.975 for DT and 0.935 for RF). On average across all components, GB exceeded RF by approximately 3.8 percentage points in Balanced Accuracy and demonstrated greater stability in MCC and Macro F1-scores. These results confirm GB as the most reliable overall performer among the three models.

4.4. Effect of Integrating Environmental Variables

The excellent performance of the DT across all bridge components highlights the critical role of integrating environmental conditions with traditional structural metrics in predicting bridge deterioration (as shown in

Table 3). In this study, a feature selection and importance analysis identified several key predictors: environmental variables driving deterioration trends, while bridge age (time in service since construction or last major rehabilitation) stood out as the most critical structural attribute, with traffic load measures (e.g., Average Daily Truck Traffic) and certain design attributes (material, span length, etc.) also contributing significantly. This finding is consistent with recent research. For example, ref. [

54] reported that age is the single most important factor in bridge deck degradation, but closely followed by environmental stressors like freeze–thaw cycle counts and rainfall, as well as heavy truck traffic volumes. The study results align with that pattern: age and traffic set the baseline rate of wear, and environmental factors modulate that rate, often accelerating deterioration in harsh climates. The inclusion of climate variables in the DT model led to tangible improvements in predictive performance, as evidenced by the near-perfect metrics obtained, a clear contrast to models trained without those inputs. In practical terms, this means the integrated model was much better at catching those bridges that, due to environmental exposure, deteriorate faster than what one would expect from age or traffic alone. These improvements demonstrate that while the algorithms employed are established, the novelty of this work arises from enhancing them with climate-driven variables and advanced evaluation procedures, which significantly extend their utility for infrastructure asset management beyond prior approaches.

The RF results across all three bridge components underscore the critical importance of integrating environmental conditions with traditional structural metrics. Overall, the RF model attained very high balanced accuracies (≈0.93) and macro F1-scores (≈0.96) for deck, superstructure, and substructure alike, a performance level that was unattainable by the baseline model lacking environmental inputs (see

Table 3). This performance validates the hypothesis that considering both climate exposure and structural characteristics yields more predictive power [

54].

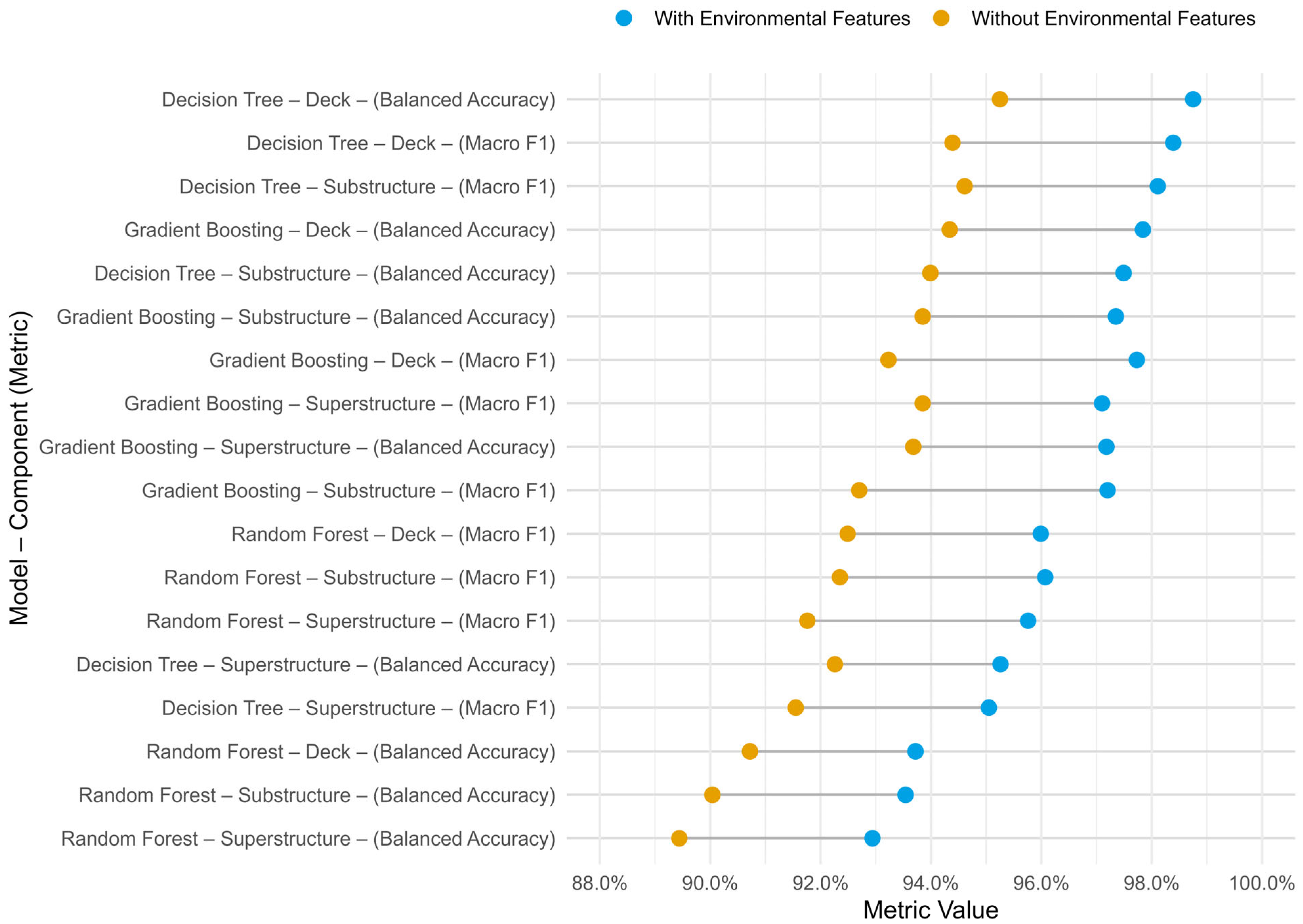

Table 3 presents the comparative results, showing that integrating environmental conditions improved balanced accuracy and macro F1-scores by 3.0 to 4.5 percentage points, corresponding to a 6–15% reduction in relative error rates for deterioration forecasting.

Traditional factors such as age and heavy traffic (ADT/ADTT) remain fundamental drivers of deterioration, as expected, but environmental stressors significantly influence the rate and severity of damage [

54]. The synergy between these types of features is evident in the RF model’s performance, and each component’s condition is best predicted by a combination of intrinsic properties and external exposures [

37]. The results here reinforce the consensus that comprehensive models provide superior predictions for infrastructure health. In practical terms, this means that bridge management agencies can achieve more reliable deterioration forecasts by incorporating climate data, which supports a shift toward proactive maintenance strategies. Studies have noted that predictive models leveraging environmental inputs enable earlier detection of critical deterioration, leading to optimized maintenance planning and improved lifecycle outcomes. The RF model’s success thus highlights the value of an integrated approach: environmental and structural metrics together produced a robust predictor of bridge deterioration, ultimately contributing to more resilient and cost-effective bridge maintenance programs.

Figure 4 presents the measurable performance gains achieved when environmental variables are included in the models. Results are shown separately for Decision Tree, Random Forest, and Gradient Boosting classifiers, across all bridge components (deck, superstructure, substructure) and evaluation metrics (Balanced Accuracy, MCC, and Macro F1). Improvement values are calculated as the difference between performance with environmental variables and performance without them. These results demonstrate that environmental stressors, particularly freeze–thaw cycles, annual rainfall, and extreme temperatures, play a critical role in accelerating bridge deterioration and should be explicitly accounted for in predictive frameworks [

4,

21]. The improved predictive capability offered by the integration of environmental variables supports the adoption of risk-informed maintenance strategies tailored to regional climatic conditions. Such approaches enable transportation agencies to better allocate resources and proactively schedule inspections for bridges most vulnerable to environmental degradation.

5. Discussion

This study developed predictive models to estimate the deterioration of bridge components using structural, operational, and environmental data from the Colorado National Highway System. The findings demonstrate that integrating environmental variables significantly improves predictive accuracy, underscoring the important role that climatic conditions play in the degradation of bridge infrastructure.

The feature importance analysis revealed that sufficiency rating is the most influential predictor across all models, corroborating findings from earlier studies where overall structural adequacy indices were shown to capture composite deterioration effects effectively [

37,

53]. Variables such as year of construction, geographical coordinates, and approach roadway width also ranked highly, consistent with prior evidence linking bridge age and design parameters to deterioration rates [

38,

39]. The consistent prominence of geographic coordinates reflects the spatial heterogeneity of deterioration mechanisms, reinforcing previous work that highlights regional differences in structural performance due to localized climate and environmental stressors [

4]. The model outcomes are influenced to some extent by the selected correlation threshold and resampling parameters. However, these choices are consistent with prior studies in bridge deterioration prediction, and sensitivity checks conducted during development indicated that moderate variation in these parameters did not materially alter the ranking of predictor importance or relative model performance [

37,

39,

52].

A notable contribution of this study is the explicit integration of environmental factors into the predictive framework. Climatic variables such as freeze–thaw cycles, precipitation, condensation risk, and extreme temperatures emerged as key predictors influencing deterioration patterns, which aligns with previous research emphasizing the vulnerability of transportation infrastructure to environmental conditions [

21]. Our results demonstrate that including these variables improves balanced accuracy and F1-scores by up to 4.5 percentage points, confirming the hypothesis that environmental stressors accelerate deterioration processes in cold and variable climates. This finding reinforces the conclusions of [

4], who demonstrated that freeze–thaw activity substantially contributes to deck cracking and delamination in regions with fluctuating winter temperatures.

Comparative model performance shows that the GB classifier outperformed DTs and RFs across most evaluation metrics. This supports earlier findings that ensemble-based learning techniques are highly effective for complex predictive tasks involving heterogeneous datasets [

38,

39]. While DTs offered interpretability and computational efficiency, their relatively lower predictive performance underscores the importance of leveraging advanced ensemble methods when dealing with highly imbalanced datasets such as this one. Furthermore, the successful application of SMOTETomek resampling to address class imbalance highlights the necessity of adopting robust data balancing strategies when predicting minority deterioration classes, which is a challenge often reported in bridge condition modeling literature [

37].

From a methodological standpoint, this study also made several design choices to ensure robustness and scalability. A correlation threshold of 0.9 was applied to reduce redundancy among predictors while retaining sufficient explanatory features, a level consistent with prior infrastructure deterioration studies [

39,

52]. In addition, Support Vector Machines were excluded after preliminary testing showed minimal performance gains (<0.5% difference in balanced accuracy) compared to tree-based models, while requiring substantially greater computation time on the full dataset. These choices ensured that the models remained both transparent and computationally feasible while maintaining high predictive performance.

Beyond the numerical gains, the variations observed in predictor importance reflect meaningful physical and operational processes. For instance, fluctuations in the relative influence of environmental indicators such as freeze–thaw frequency and precipitation intensity are closely tied to the geographic and material heterogeneity of Colorado’s bridge inventory. Older concrete structures with lower sufficiency ratings exhibited stronger sensitivity to temperature extremes and moisture cycles, suggesting interaction effects between structural age, material composition, and local climate. Similar dependencies were reported by [

37,

54], who found that climatic exposure amplified deterioration rates in aging decks even under moderate traffic loads. In contrast, the relatively stable ranking of geometric variables such as approach width and span length indicates that design parameters exert consistent, long-term influence irrespective of environmental variation. These patterns demonstrate that deterioration is governed by both intrinsic structural factors and extrinsic environmental stressors, reinforcing the importance of multivariate modeling frameworks that capture such cross-dependencies.

From an engineering standpoint, the observed 3–4.5% improvement in accuracy yields tangible value when scaled to network-level decision-making. Even marginal gains can shift the prioritization of dozens of bridges toward timely maintenance, preventing cost escalation associated with deferred rehabilitation. This aligns with recent findings by [

39,

52], who emphasized that interpretability and deployment feasibility often outweigh raw algorithmic novelty in transportation asset management. Thus, the proposed climate-informed modeling approach balances predictive performance, transparency, and computational efficiency, offering a practical pathway for integrating environmental intelligence into existing maintenance workflows.

The implications of these findings are significant for infrastructure management and maintenance planning. Transportation agencies can utilize such predictive models to prioritize inspection schedules and optimize resource allocation, particularly for bridges most vulnerable to environmental stressors. In addition, identifying the sufficiency rating as the dominant predictor suggests that existing composite indices remain useful for deterioration assessment but should be supplemented with region-specific environmental metrics to improve forecasting reliability. The findings confirm that the methodological contribution of this study does not lie in proposing entirely new algorithms but in demonstrating how established models can be systematically enhanced through integration of environmental stressors, advanced imbalance handling, and rigorous evaluation. This innovation provides transportation agencies with climate-informed tools that improve the reliability and accuracy of deterioration forecasting.

6. Conclusions and Future Research

This study developed and evaluated machine learning models to predict the deterioration of bridge components using a combination of structural, operational, and environmental data for bridges on the Colorado National Highway System. Among the algorithms tested, the GB classifier consistently outperformed DTs and RFs across multiple evaluation metrics, achieving balanced accuracy values between 97.2% and 97.8% and Matthews Correlation Coefficients near 0.97 across bridge decks, superstructures, and substructures. In contrast, RF and DT models achieved balanced accuracy—between 93 and 95% and 95–98%, respectively—demonstrating the superior predictive stability of GB. Feature importance analysis revealed that the sufficiency rating remains the most influential predictor of deterioration, but environmental variables ranked highly across all models. Integrating these variables improved predictive accuracy by 3.0–4.5 percentage points compared to models without climate data, underscoring the importance of incorporating regional climatic stressors into deterioration modeling. The results support the adoption of climate-aware predictive frameworks capable of adapting maintenance strategies to evolving environmental conditions.

Despite the robustness of the results, some limitations warrant attention. First, while the models incorporated a rich set of environmental variables, other relevant stressors, such as chloride concentrations from de-icing salts, wind loading, and seismic activity, were excluded due to limited data availability. Future research should aim to integrate these factors where possible, particularly given their known impacts on corrosion and structural fatigue. Second, the models were developed using bridges within Colorado’s National Highway System, and while geographic coordinates partially capture spatial variability, generalizing findings to other regions with different climatic conditions will require external validation on broader datasets. Finally, while this study compared three prominent machine learning algorithms, exploring deep learning architectures and hybrid modeling approaches could further enhance predictive capabilities, particularly for large-scale national datasets.

Although this study focused on Colorado bridges, the methodology is broadly transferable. The standardized nature of NBI data and the availability of equivalent climate datasets in other regions make it possible to apply the same framework elsewhere. Minor adjustments for local conditions may be required, but the integration of structural and environmental variables ensures that the model design is generalizable. In future work, predictive frameworks could also be extended to incorporate real-time monitoring data from embedded sensors and Internet of Things (IoT) systems, allowing dynamic updating of deterioration forecasts. Such integration would facilitate proactive decision-making and improve the resilience of transportation infrastructure under evolving climatic conditions.