1. Introduction

Posturographic studies play a crucial role in the diagnostic assessment of both static and dynamic balance. Depending on the population being studied, this assessment can be geared towards evaluating the efficiency and effectiveness of motor tasks, such as in sports, or towards fall risk assessment and prevention, a significant societal concern, particularly among older adults [

1]. Mobility is a key prerequisite for the independence and autonomy of older individuals, underpinning their ability to perform activities of daily living, including self-care, shopping, and regular walks.

Numerous research teams have focused on the elevated risk of falls in the elderly [

2,

3,

4,

5]. Falls and their associated complications represent a genuine public health issue and, importantly, impact the quality of life of older individuals [

1]. Consequently, research on balance control in this age group is extensive [

4,

5,

6]. As highlighted by Du Pasquier R. A. et al. (2003), understanding postural stability during human involution is critical for distinguishing between physiological and pathological processes [

7]. Accurate diagnosis relies on knowledge of which stabilographic measures, or measures of human balance quality, are significantly associated with susceptibility to falls [

8,

9]. The widespread use of balance assessments in individuals with well-defined postural strategy deficits holds the greatest potential for improving our understanding of the links between specific neurophysiological impairments and measured Center of Pressure (COP) parameters [

10,

11].

Assessing the effect of external loads on changes in postural stability, especially in older adults, is complex [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. This is because postural stability—the ability to maintain the body’s center of mass within its base of support—is not just a simple measure. It is a dynamic process influenced by multiple factors, including vision, proprioception, and the vestibular system. When an external load is introduced, the body must make continuous adjustments to maintain equilibrium [

18,

19]. The research by Zultovsky and Aruin [

13] underscored this complexity by showing that the magnitude and location of the load and the size of the support surface all play crucial roles in how a person’s balance is affected. For older adults, who may already experience age-related declines in these systems, even small disruptions can significantly increase the risk of falls.

While some studies have looked at external loads, most have focused on symmetrical loads, such as a backpack or a weighted vest, that distribute weight evenly across the body. A key research gap is the lack of studies on asymmetrically distributed loads, specifically those applied to the right and left shoulders. This is a critical oversight because carrying a bag on one shoulder creates a continuous, off-center pull. This forces the body to make a series of compensatory movements and muscular adjustments to prevent tipping, which could be particularly taxing for an aging body. The body may have to shift its weight to the opposite side, activate different muscles to a greater extent, or even alter the natural gait pattern to maintain balance [

19]. Understanding these specific effects is vital for developing fall prevention strategies and providing informed guidance to the elderly.

We aimed to test our hypothesis that even small, asymmetrical loads can alter an individual’s center of pressure (COP). The hypothesis was based on biomechanical principles of load magnitude rather than laterality effects. The primary goal of our study was to compare the static postural control of older adults with a control group when they were asymmetrically loaded. We anticipated that while the middle-aged group would show better overall postural performance, the direction of changes in postural strategies under experimental conditions would be similar for both groups. Additionally, we expected that loading the right versus the left shoulder would produce similar differences in postural control for both study groups.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

This study involved two independent groups: older (OP) and younger adults (YP). The older adult participants lived in a shared living environment that provided stable, scheduled meals and consistent access to medical care, rehabilitation services, and physical exercise programs. The inclusion criterion was over 65 years. Exclusion criteria included any history of upper or lower limb injuries, presence of dizziness, or any active disease. The younger participants were professionally active and had gainful employment. The inclusion criterion for the study was age 25–40 years. Exclusion criteria included any history of upper or lower limb injuries. Handedness and habitual load-carrying side were not recorded. Physical activity level, manual dominance, and previous experience with loads were not systematically assessed. Prior to participation, all individuals were thoroughly informed about the study’s purpose, methodology, and experimental procedures. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant. The study received approval from the local bioethics committee, and all experimental procedures were conducted following the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Older participants were examined at their place of residence (the Nursing Home), while younger participants were examined at the biomechanics workshop of the Faculty of Physical Education and Physiotherapy at Opole University of Technology.

The study sample comprised thirty-three older adults (mean age = 72.18 years, standard deviation = 11.01, height = 157.94 ± 6.49, weight = 74.71 ± 15.56) and twenty-seven younger adults (mean age = 33.5 years, standard deviation = 15.8, height = 175.69 ± 6.15, weight = 73.96 ± 14.27).

2.2. Postural Balance Assessment

Postural balance was assessed using a Kistler force plate (Winterthur, Switzerland) sampling at 20 Hz in a quiet room with a firm floor, uniform lighting, and a fixed visual target at eye level. Participants received the following instructions: “Stand as still as possible, look at the target, breathe normally, and avoid talking or moving unnecessarily”. Data were collected over three consecutive 20 s conditions with eyes open, presented in a randomized order:

(NL) No Load: Free-standing position without any external load.

(LL) Left Load: Free-standing position with a 3 kg load (a soft-strap shoulder bag) asymmetrically distributed on the left arm. The upper limbs were positioned along the torso in a natural position. The left arm was touching the bag. The bag did not contact external supports and allowed for natural tactile contact with the shoulder/upper arm.

(LR) Right Load: Free-standing position with a 3 kg load (a soft-strap shoulder bag) asymmetrically distributed on the right arm. The upper limbs were positioned along the torso in a natural position. The right arm was touching the bag. The bag did not contact external supports and allowed for natural tactile contact with the shoulder/upper arm.

A 60 s seated rest was provided between trials to minimize fatigue. All trials were performed with the participants barefoot. Prior to parameter calculation, the raw COP data were processed using custom scripts in MATLAB (R2021a, MathWorks, Natick, USA). Postural balance was quantified using four parameters derived from the center-of-pressure (COP) time series recorded during each trial: standard deviation (SD), range (RA), mean velocity (MV), and sample entropy (SE). These parameters were analyzed separately in both the medial-lateral (ML) and anterior–posterior (AP) directions [

20,

21]. The standard deviation quantifies the variability of the COP signal, reflecting the degree of sway and the participant’s overall steadiness during standing. A higher SD indicates greater fluctuations in balance, often interpreted as reduced postural control. Range measures the maximum excursion of the COP in both the medial-lateral and anterior–posterior directions, representing the limits of sway. A larger range suggests that a participant’s center of mass moves further from the neutral standing position, which may correspond to decreased control or increased compensatory movements. Mean velocity computes the average speed at which the COP shifts throughout the trial. This parameter is sensitive to subtle compensatory adjustments and overall activity in maintaining balance. Elevated mean velocity is generally associated with less efficient postural control as it indicates more frequent or larger corrective movements. Sample entropy is a nonlinear measure that assesses the complexity and regularity of the COP time series. Higher entropy values imply more unpredictable and adaptable balance strategies, while lower values may signal stereotyped or rigid postural adjustments. SE was based on m = 3 and r = 0.1 × SD parameters calculated with MATLAB function sampen.m available at

www.physionet.org.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Prior to analysis, the data were checked for normality using appropriate tests, revealing no significant deviations from a normal distribution only for SE. Homogeneity of variances across the studied groups was also confirmed only for SE. In light of this, a logarithmic (natural base) transformation was applied to the remaining parameters. To examine the effects of group, loading condition, and plane of movement on the COP parameters, a mixed-design analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted with Group (older adults, younger adults) as a between-subjects factor and Test (no load, left load, right load) and Plane (ML, AP) as within-subjects factors. The assumption of sphericity was assessed using Mauchly’s test. Post hoc pairwise comparisons between the two groups were performed using the t-test with Tukey correction. The significance level was set at p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using STATISTICA 13 software.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the potential negative impact of carrying a small (3 kg) asymmetrical load (on the left or right shoulder) on the postural control of older adults, with younger adults serving as a comparison group. The findings revealed a nuanced picture.

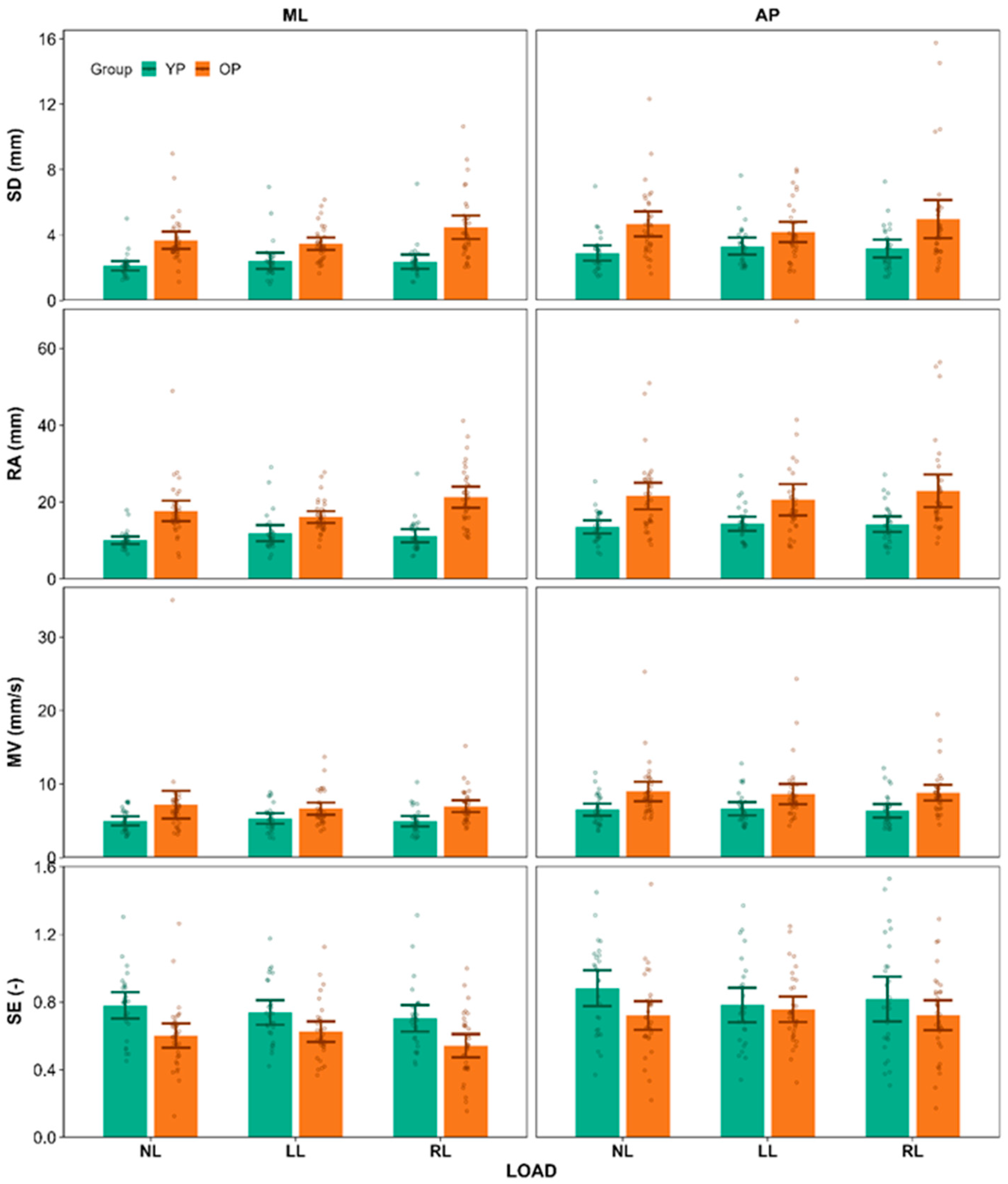

Consistent with numerous previous studies [

22,

23], our results demonstrated generally superior postural control in the younger group compared to the older group. This was evidenced by significantly lower values of center-of-pressure (COP) variability (SD and RA) and mean velocity (MV). Furthermore, the higher sample entropy (SE) observed in the younger adults suggests more adaptable and efficient postural control strategies. Higher SE values are often interpreted as reflecting greater complexity and irregularity in the COP signal, indicative of a more flexible and responsive control system capable of adapting to perturbations [

20,

24].

However, contrary to our initial hypothesis, the introduction of a small asymmetrical load did not appear to negatively affect the postural control of the older group. Notably, the younger group’s postural control remained consistent across all loading conditions. This suggests a potential resilience to small external loads in both age groups.

Interestingly, the interaction effect illustrated in

Figure 1 revealed a more complex relationship. While no significant inter-group differences were observed when the load was placed on the left shoulder, the older adults exhibited poorer postural control compared to the younger adults in the no-load condition and when the load was on the right shoulder. This suggests that the asymmetrical load on the left side might have triggered a compensatory mechanism specifically in older adults. Very similar results when carrying a load with hand were reported in [

14] and proposed as a beneficial change in postural control, and [

15], whose authors considered it as a limitation of postural control. In contrast, our results concerned the COP amplitude, a lower value of which is almost always a manifestation of better balance and decreased risk of falls [

25].

This observed benefit of the left-sided load in the older group could be indicative of an equilibrium adjustment mechanism that is more readily utilized by older adults than their younger counterparts. The younger individuals, possessing inherently more robust postural control, may not need to engage such mechanisms, potentially reflecting a “floor effect” where their performance is already near optimal [

16]. Alternatively, older adults might rely more on external sensory cues to maintain stability [

14,

16] as their intrinsic control mechanisms decline with age.

We speculate that this compensatory mechanism might be facilitated by the additional sensory information provided by the contact of the load with the left arm and shoulder. This tactile input could potentially act similarly to “light touch”, a phenomenon repeatedly shown to improve postural stability by providing supplementary sensory cues that aid in orientation and balance control [

26,

27,

28]. The subtle pressure and proprioceptive feedback from the load might provide older adults with an external reference point, enhancing their ability to regulate body sway.

The intriguing finding that the small asymmetrical load appeared to benefit postural control in older adults only when applied to the left shoulder warrants further consideration. One potential explanation for this asymmetry could be related to the handedness of the participants. If most of the older adults in our sample were right-handed, they might have developed a habitual pattern of carrying bags or other loads on their non-dominant (left) side. This habitual loading could have led to enhanced proprioceptive awareness and a more refined sensorimotor integration on the left side, potentially facilitating a more effective compensatory response when a load is introduced there.

Individuals who predominantly use their right hand for manipulation often develop a greater reliance on the left side for balance and stability during asymmetric tasks [

29]. Carrying a bag on the left shoulder becomes a familiar and perhaps even subconsciously stabilizing action over time. The sensory feedback from this familiar loading pattern might be more readily processed and integrated into the postural control system of right-handed older adults compared to an unfamiliar load on the right side. This could explain why the left-sided load provided a beneficial sensory cue that improved stability, whereas the right-sided load, being less familiar, did not elicit the same positive effect or might have even introduced a novel perturbation that the system was less adept at handling.

Future work should include handedness and preferred load-carrying side as explicit factors for stratified analysis. Stratifying the analysis based on handedness could reveal whether this left-side benefit is indeed more pronounced in right-handed individuals. Furthermore, investigating the participants’ history of carrying loads and their preferred shoulder for carrying bags could provide valuable contextual information.

It is also worth considering potential biomechanical differences between loading the left versus the right shoulder. Subtle variations in muscle activation patterns, joint kinematics, or the distribution of the load’s center of mass relative to the body’s center of mass depending on which shoulder is loaded could contribute to the observed asymmetry. However, given the small magnitude of the load (3 kg), it is plausible that the dominant factor is the familiarity and the resulting enhanced sensory processing associated with the habitually loaded (typically non-dominant) side in right-handed individuals.

Beyond the potential benefits of a familiar left-sided load, the observed difference in response when the load was shifted to the right arm could also indicate a potential vulnerability in the older adults’ postural control system when faced with a novel or unexpected asymmetrical perturbation. For individuals with age-related declines in proprioception, muscle strength, and reaction time, the introduction of an unfamiliar load on their less habitually loaded side (potentially the dominant right side for many) might present a greater challenge to their balance. This novel asymmetry could disrupt established compensatory strategies and require the engagement of less efficient or less practiced neural pathways for postural adjustments. The increased postural sway observed with the right-sided load in the older group might reflect this difficulty in adapting to a new asymmetrical weight distribution. This suggests that while familiar, consistent asymmetrical loading (like carrying a bag on the non-dominant side) might be accommodated or even utilized for stability, a sudden shift or the introduction of an unexpected load on the other side could pose a greater risk of instability and potentially increase the likelihood of falls in older adults. Therefore, interventions or daily activities involving asymmetrical loading should consider the individual’s habits and potentially avoid sudden or unexpected shifts in weight distribution, especially onto the dominant side.

In summary, the potential influence of handedness and habitual loading patterns offers a compelling avenue for understanding the observed asymmetry in the effect of the small load on postural control in older adults. The results suggest that small asymmetrical loads might not necessarily impair postural stability in older adults when placed on the left shoulder, though this effect requires confirmation in larger and more controlled studies considering handedness and habitual load-carrying patterns. Future studies that account for these factors are crucial for a more comprehensive understanding of how external loads interact with the aging postural control system.

Several important limitations should be acknowledged when interpreting the findings of this study. Our study focused specifically on eyes-open conditions to reflect typical daily activities where visual information is available. We acknowledge that eyes-closed testing and proprioceptive manipulation (e.g., foam surfaces) would provide additional insights into sensory integration and could help differentiate the contributions of different sensory systems. This is also a direction for future research.

Most notably, the collection of only one trial per experimental condition is a significant methodological constraint that may have affected the reliability and generalizability of our postural control measurements. While multiple trials are generally preferred to establish reliable measures and account for trial-to-trial variability, this approach was deliberately chosen due to the specific characteristics of our older adult population. Community-dwelling older adults often experience fatigue and decreased motivation during prolonged testing sessions, which can significantly impact their performance and introduce confounding variables. Given that our participants were required to maintain postural stability while carrying asymmetric shoulder loads (a potentially challenging and unfamiliar task), extending the testing protocol to include multiple trials per condition would have likely resulted in fatigue-related performance decrements that could mask the true effects of the load manipulation.

The use of only one trial per condition represents a key methodological constraint that may have affected the reliability of our measurements, particularly for complex variables such as entropy. While multiple trials are generally preferred, this approach was deliberately chosen to minimize fatigue and maintain motivation in our older adult population during an already challenging task involving asymmetric shoulder loads. Future studies with multiple trials per condition would help establish more robust reliability estimates for these measures in older adults under asymmetric loading conditions.

Furthermore, our study design was only powered to detect large effect sizes (with 80% power and 5% significance level), which may have resulted in the failure to identify clinically meaningful but smaller differences in postural control. However, it is reasonable to assume that only large effect sizes in postural stability measures translate to meaningful implications for everyday life scenarios in older adults such as maintaining balance during household tasks, navigating uneven surfaces, or recovering from perturbations during daily activities.