Abstract

Rainbow table attacks utilize a time-memory trade-off to efficiently crack passwords by employing precomputed tables containing chains of passwords and hash values. Generating these tables is computationally intensive, and several researchers have proposed utilizing parallel computing to speed up the generation process. This paper introduces a modification to the traditional master-slave parallelization model using the MPI framework, where, unlike previous approaches, the generation of starting points is decentralized, allowing each process to generate its own tasks independently. This design is proposed to reduce communication overhead and improve the efficiency of rainbow table generation. We reduced the number of inter-process communications by letting each process generate chains independently. We conducted three experiments to evaluate the performance of the parallel rainbow tables generation algorithm for four cryptographic hash functions: NTLMv2, MD5, SHA-256 and SHA-512. The first experiment assessed parallel performance, showing near-linear speedup and 95–99% efficiency across varying numbers of nodes. The second experiment evaluated scalability by increasing the number of processed chains from 100 to 100,000, revealing that higher workloads significantly impacted execution time, with SHA-512 being the most computationally intensive. The third experiment evaluated the effect of chain length on execution time, confirming that longer chains increase computational cost, with SHA-512 consistently requiring the most resources. The proposed approach offers an efficient and practical solution to the computational challenges of rainbow tables generation. The findings of this research can benefit key stakeholders, including cybersecurity professionals, ethical hackers, digital forensics experts and researchers in cryptography, by providing an efficient method for generating rainbow tables to analyze password security.

1. Introduction

In the field of information security, passwords play a key role in protecting information systems, resources and services [1]. Due to the sensitive nature of passwords, they are not stored in plain text but rather in an unreadable format, known as a hash value or digest, which is generated as an output from a cryptographic hash function [2]. This function converts a password of an arbitrary length to a fixed-length value. This process adds a layer of security by making it more difficult for hackers to decipher the original password from the stored hash value. Another security mechanism that can be used to enhance password security is password salting. This method involves adding a unique, random string (called a salt) to each password before hashing it. This makes the rainbow tables technique, which was, historically, highly effective against password hashes, computationally infeasible [3]. However, the topic of salted passwords is out of the scope of this paper due to our focus on optimizing rainbow tables generation for modern cryptographic hash functions.

Cryptographic hash functions are designed as a one-way function, meaning that it is impossible to invert the function and find the original password given the hash value. Instead, malicious actors obtain the hash value via compromise or exfiltration and use indirect methods to find out what the password is. The most common and well-known approach is brute force attack [4], which is the most effective approach but also highly time-consuming and resource-intensive, especially for long and complex passwords. Brute force attack involves trying every possible combination of characters until the correct password is found. Another approach is dictionary attack [4,5], which involves testing passwords from a pre-arranged list of words and known passwords from past data breaches. Dictionary attack is effective only in some cases, specifically for passwords that are simple, short, common, and easy to guess. If the passwords are long and complicated, they are unlikely to appear in any known dictionary.

In 2003, Oechslin [6] introduced a new method for password cracking called rainbow tables attack, which is based on the earlier work from Hellman [7], who was the first to propose using a time-memory trade-off for cryptanalysis. It is important to understand this evolution, as the current research builds directly on these principles to enhance the efficiency of rainbow tables generation using different parallel computing methods.

A time-memory trade-off occurs when an algorithm or program exchanges increased memory usage for reduced execution time. In this context, memory refers to the data storage resources used during task execution, such as random access memory (RAM) or hard disk space, while time refers to the time required to complete the task.

In the context of rainbow table attack, a large, precomputed table containing passwords and hashes is generated prior to the password cracking process to reduce the time it takes when performing the attack itself. It is clear that generation of such tables, especially with large dimensions, requires a significant amount of time and computational power. Naturally, parallel computing is perceived as an obvious way to increase computational capabilities. However, the selection of the efficient parallel algorithm is highly dependable on the research field, the considered problem and the method used [8,9,10].

While the effectiveness of rainbow table attacks has declined in modern systems due to widespread adoption of password salting [11] and GPU capabilities [12], these techniques remain relevant in scenarios involving legacy systems, poorly configured authentication mechanisms or digital forensic investigations. In such contexts, the ability to rapidly generate large and diverse rainbow tables remains of practical importance. Prior work has explored various optimization strategies for rainbow table generation, including GPU-accelerated, FPGA-based, and MPI-based methods, each with different trade-offs in performance, scalability, and implementation complexity.

Our proposed method’s contribution is a modified and improved implementation for parallelization of rainbow tables using the MPI standard based on the structure of the master-slave approach, which is more efficient and convenient for this task. The approach differs from the traditional master-slave model by introducing a modification in the task distribution: instead of the master distributing starting points to each slave process, each process generates them independently, which is more efficient. This design eliminates the need for the master to coordinate task distribution, which is a well-known performance bottleneck in traditional MPI-based master-slave parallelization models [13,14]. As a result, our method significantly reduces inter-process communication, improves scalability and maintains high parallel efficiency even with limited computational resources.

MPI relies on communication between processes for parallelization, and most MPI-based algorithms require efficient communication to minimize latency and maximize computational performance. However, MPI communications require time due to factors such as latency, bandwidth limitations, network topology and communication overhead. Communication overhead in particular requires thoughtful consideration, and reducing it is the key to improving the performance of MPI-based algorithms. In the master-slave parallelization model, the communication overhead can be significant due to the way tasks and data are distributed between the master (which controls task assignment) and the slave processes (which perform computations). The overhead in this model comes from several key factors; the most relevant is the sending of messages and the use of message buffers. In this paper, we modified the master-slave model to reduce the number of point-to-point communications and improve the overall performance of the parallel algorithm.

The paper consists of five additional sections. Section 2 provides a comprehensive literature review on cryptographic hash functions and cryptanalytic time-memory trade-offs leading to parallel computing methods for rainbow tables generation. Section 3 presents the proposed method for parallel rainbow tables generation using MPI. The experimental results are presented in Section 4. Section 5 addresses the limitations of the research and suggests areas for future work. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Related Work

In this section, we provide a comprehensive literature review on the topics of cryptographic hash functions, cryptanalytic time-memory trade-offs and parallel computing methods for rainbow tables generation. The first subsection provides a review of cryptographic hash functions and their properties. These functions are an integral part of the rainbow tables generation process. The second subsection presents the historical evolution of cryptanalytic time-memory trade-offs, of which rainbow tables are the most popular. The last subsection covers the current methods and approaches used for rainbow tables generation by utilizing parallel computing methods.

This structure is meant to provide logical progression from fundamental cryptographic concepts to the specific problem domain addressed in this paper. By addressing these three areas, we place our proposed method in the context of both the theoretical background and the current state of the art in parallelized rainbow tables generation.

2.1. Cryptographic Hash Functions, Their Properties and Attacks

A hash function is a function that can be used to map data (message) of arbitrary size to fixed-size values. This concept of hashing was introduced for the first time by Hans Peter Luhn [15] in 1958. However, the security was not taken into consideration. In fact, its purpose was not to secure passwords or to ensure data integrity but to organize information so that it is easy for a computer to find. Hash functions are extensively used in different research fields, such as neighbor search, particuology and computer graphics [16,17]. Cryptographic hash functions are a more sophisticated variant of a hash function with additional properties suitable for cryptographic applications.

The first and most important property is the collision resistance. According to this property, given a hash function h, it should be difficult to find two different messages and such that . Finding hash collisions is important to password security, as a hash function, which lacks the property of collision resistance, cannot be used for password hashing, and the task of cracking passwords becomes easier for malicious actors. That is, if a hash function is not collision resistant, then an attacker will no longer need to find a specific password. Instead, any password that corresponds to the same hash value will work. Some researchers found collisions for different hash functions like MD5, SHA-1, and others [18,19,20].

Another property commonly discussed in the literature on cryptographic hash functions is the pre-image resistance. This property states that given a hash value y and a hash function h, it should be difficult to find any message m such that . Hash functions that lack this property are vulnerable to preimage attacks. This vulnerability has been explored in research, such as in the work of Nkouankou et al. [21], who looked for pre-images of the MD5 hash function using propositional logic inspired by the concept of boolean satisfiability problems. Another attempt was made by Zhong et al. [22] for the DHA-256 hash function, which was proposed at the Cryptographic Hash Workshop organized by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in November 2005. This property is also related with the concept of a one-way function, which states that cryptographic hash functions should be easy to compute on every input but hard to invert given a random output. Dobbertin [23] showed that the first two rounds out of three of MD4 are not one-way, and, as a result, a pre-image can be found efficiently.

The last and final property of cryptographic hash functions is the second pre-image resistance. Given an input , it should be difficult to find a different input such that for a given hash function h. This property is also known as weak collision resistance. Hash functions that lack this property are vulnerable to second-preimage attacks. Several studies have explored the importance of second pre-image resistance in cryptographic hash functions that fail to meet this property. For example, Kelsey et al. [24], Sulak et al. [25] and Andreeva et al. [26] presented second preimage attacks on different hash functions including RIPEMD-160, LUX and other cryptographic hash functions.

Lack of any of these three critical properties is an indication of a weak and insecure hash function. Therefore, when choosing a cryptographic hash function for security applications, it is important to ensure that it exhibits all these properties to safeguard against potential attacks. At the same time, it is important to notice the difference between attacks on cryptographic hash functions and password cracking attacks. Those are two separate types of attacks; the first is used to exploit vulnerabilities in the hash algorithm itself, and the second is used to recover or guess the original password from the hash value, which is the output of a cryptographic hash function.

2.2. Evolution of Cryptanalytic Time-Memory Trade-Offs

The first application for time-memory trade-off to cryptanalysis was introduced by Hellman [7]. Prior to performing the attack, the Hellman table must be constructed. For this purpose, m starting points are chosen independently at random from the set of possible passwords. Each password in the set of starting points is transformed by repeatedly applying a hash function followed by a new type of function called a reduction function, typically denoted as R. The two functions are sequentially applied for t times to form a chain. The first (starting point) and last (endpoint) elements of the chain form a new entry in the Hellman table, and the table is then sorted on the end points to allow for a fast search using a binary search algorithm.

Although Hellman’s method allows the quick inversion of hash functions, it still suffers from a few practical limitations. One limitation was noted by Ron Rivest and was referenced in the book Cryptography and Data Security [27]. Rivest observed that the search time is influenced by the number of reads on the hard disk and proposed to reduce the time by forcing the endpoint of a chain to satisfy a specific property such as a point that begins with a fixed number of zeros. In other words, the stopping condition for computing the endpoint of a chain is no longer reaching the desired value of t; instead, it is reaching an endpoint that satisfies a specific property. Such an endpoint is called a distinguished point, which leads to chains of different lengths. This, indeed, allows us to reduce the number of lookups to the hard disk, but at the same time, it introduces additional challenges when dealing with merges in the constructed chains. Those merges are encountered when at some point in at least two chains we come across an identical value. Starting from this value, the chains are identical. This has been a common issue in cryptanalytic time-memory trade-offs since they were first introduced in 1980.

Rainbow tables [6] introduced a modified structure for the table construction that uses a different reduction function at every step of the chain generation process. This slight change helps to identify chain merges more easily. With rainbow tables, if a merge is identified in at least two chains, the merge will occur in the same column in both chains. When using rainbow tables for cracking LM Windows hashes, Oechslin [6] demonstrated that 99.9% of all alphanumeric password hashes (237) could be cracked in just 13.6 s. This high crack rate is due to notable algorithmic weaknesses in LM hashes. In comparison, the approach using distinguished points [27] required 101 s to achieve the same result. Rainbow tables were further improved over the years. In 2008, Avoine et al. [28] introduced the concept of checkpoints, which are some positions on the chains where a test is applied. This test is typically a parity check that allows filtering out false alarms without regenerating the chains from scratch. Another improvement is an optimal storage for rainbow tables, which was proposed by Avoine et al. [29]. The proposed approach is a new method for storing the endpoints of rainbow tables called compressed delta encoding. This approach aims to significantly reduce the memory required for storing these tables compared to existing methods. A more recent improvement to rainbow tables is the one proposed by Quan et al. [30]. They utilized quantum computing and Grover’s algorithm to improve the efficiency of the rainbow table attacks by developing a quantum rainbow table called QIris. The generation of the quantum rainbow table in QIris involves the classical precomputation of rainbow chains using multiple reduction functions. The final plaintexts of these chains are then processed using a simplified hashing method, and their resulting 16-bit integer representations are organized into buckets based on their value ranges. This bucketed structure, along with the classical rainbow table data, facilitates the quantum-assisted search using Grover’s algorithm.

2.3. Parallel Computing Methods for Rainbow Tables Generation

The problem of rainbow tables generation has been discussed several times in the scientific literature. Various authors proposed different methods utilizing different technologies to optimize the generation process of those tables. Most papers propose utilizing parallel computing to achieve this goal.

Some solutions utilize the parallelization capabilities on the GPU. Dat et al. [31] proposed an implementation of high-speed rainbow table generation with the integrated development environment CUDA for GPU in the heterogeneous GPU + CPU system to crack passwords that were hashed with the Keccak-512 hashing algorithm. The process is rather simple, and it is split into CPU tasks and GPU tasks. Most of the work is done on the GPU, where each starting point from the CPU is processed in its own thread to generate a rainbow chain, and a corresponding end point is returned to the CPU. All starting and end points are written to a file at the end of the process. The results show that the rainbow table generation time is approximately 70 times faster than using the CPU alone with a chain length of 50. When the rainbow chain is longer, the speedup increases.

Kim et al. [32] proposed another implementation on the GPU using CUDA. They considered warp serialization, which is a concern for performance on the GPU. In addition, they used checkpoints for load balancing between the CPU and the GPU, which helped in the performance improvement. The implementation was executed on two different Nvidia GPUs and compared against equivalent implementations from RainbowCrack and Cryptohaze. In both cases, the author’s implementation performed better. The experimental results show that on the GTX460 model, the implementation runs about 1.86 and 3.25 times faster than RainbowCrack and Cryptohaze, respectively, and on the GTX580 model, it runs 1.53 and 2.40 times faster.

Li et al. [33] proposed another approach using CUDA on the GPU for high-speed perfect rainbow table generation. Their approach also includes a table storage optimization method, which reduces memory space to 57.1% compared to the tools from Cryptohaze. To parallelize the rainbow table generation, the authors employed a dynamic task scheduling strategy on a heterogeneous multi-device architecture consisting of CPU and GPUs. The entire precomputation task is evenly split into many smaller subtasks, which are then maintained in a task queue and managed by a thread pool. When a computing device (CPU or GPU) becomes idle, it continuously fetches and executes a new subtask from the task queue until the queue is empty. It can achieve 2.03× and 131.3× speedup compared to other tools like Cryptohaze and RainbowCrack, respectively.

Alternative methods for generating rainbow tables are based on the use of field-programmable gate arrays (FPGAs), offering greater efficiency and high speedup. The research on the use of FPGAs for this purpose shows impressive results. One such research was conducted by Kalenderi et al. [34] and aimed at generating rainbow tables for breaking the A5/1 stream cipher; it achieved an improvement of up to 3000 times compared to the same implementation on a personal computer with standard GPU. Another research was conducted by Papantonakis et al. [35] and intended to break the A5/3 stream cipher using rainbow tables that were generated on FPGAs using 64 computing machines. The speedup was up to 550 times faster compared to CPUs available at the time. Theocharoulis et al. [36] presented a different hardware system, which was implemented on a Xilinx XCV5VLX330T FPGA chip on a HitechGlobal card targeting the LM, SHA-1 and MD5 cryptographic hash functions. This system can generate rainbow tables up to 1000 times faster than a 2010 PC.

Sykes and Skoczen [37] and Al-Khazraji [10] both used the MPI standard to perform the rainbow table generation in parallel. Sykes and Skoczen [37] aimed to improve the implementation of a popular rainbow table attack tool called RainbowCrack, originally designed for a single CPU machine, by conducting an in-depth exploration of the existing RainbowCrack codebase. Their work was focused on rainbow tables generation targeted for Windows hashes. They achieved an impressive speedup of 400 times faster compared to generation on a single processor, decreasing the execution time from 6 years to 7 days. A different approach using MPI was proposed by Al-Khazraji [10]. He proposed using the master-slave approach to speed up the generation process. In this approach, the master distributes starting points to each slave process, and the slave processes construct the chains and send them back to the master process, which combines all chains to a single rainbow table. The implementation was executed on an environment with 250 computing nodes, where 201 nodes were used, one as a master process and the rest as slave processes. The results show an improvement in execution times and overall speedup. The parallel implementation could generate a rainbow table containing 152 MB of data in just 3.38 min instead of 816.62 min sequentially and a table with 1.48 GB of data in 46.45 min rather than 7.14 days in a serial implementation.

Another MPI-based approach was proposed by Avoine et al. [38], who introduced the concept of the stepped rainbow tables method, in which merged chains are recycled instead of being discarded, which leads to chains of shorter length compared to chains that did not merge because the merged parts are removed. In this approach, the authors discovered that stepped rainbow tables achieve a speedup of 2.56.

In addition to the more conventional GPU, FPGA or MPI-based methods, there are a few unique approaches that offer alternative perspectives and techniques for rainbow table generation. Avoine et al. [39] introduced a new technique, which the authors call distributed filtration-computation, that significantly reduces the precomputation time. The technique is based on optimally placing filters on certain columns of the rainbow table and performing filtration of merged chains. To reduce the number of non-hashing operations, filtration and chain computation are performed in parallel. The technique was demonstrated using a common scenario. In this case, the precomputation phase on a 128-core computer requires over 50 h, whereas the suggested technique was completed (including filtering) in roughly 8 h and 36 min on the same machine. Thus, the estimated precomputation time is reduced by roughly six times when applying the technique.

In 2008, a new project called Distributed Free Rainbow Tables [40] was launched on the Berkeley Open Infrastructure for Network Computing (BOINC) middleware system with the goal of generating extensive rainbow tables using the volunteer computing approach. It relied on a distributed network of volunteer computers to share the computational load, utilizing the collective processing power of participants around the world to efficiently produce large, high-quality rainbow tables for NTLMv2, SHA-1, MD5, LM and the Half LM challenge cryptographic hash functions. As of June 2024, detailed information on the performance, efficiency and implementation of the project is no longer available. Only the resulting rainbow tables remain accessible for download, as the project has been inactive since its completion in June 2014.

3. Proposed Method

The implementation proposed in this paper was written using the C++ programming language and the MPI standard, specifically the OpenMPI implementation. MPI is a standard that allows multiple processors with distributed memory (each with its own separate memory) to work together on a task by exchanging information through messages. By breaking down a large task across processors, MPI enables faster and efficient processing, making it ideal for scientific computing and simulations.

Our implementation leverages key MPI functions such as MPI_Send and MPI_Recv to exchange data and synchronize operations among processes.

The approach for the parallel rainbow tables generation is based on the master-slave parallelization model with a modification. The classic model was used by Al-Khazraji [10] and it seems to be a reasonable choice, as it makes resolving merges in rainbow tables a lot easier in a distributed memory environment.

The implementation from Al-Khazraji [10] follows the standard master-slave communication pattern, where the master generates the data and distributes it to all the slave processes, and they, in return, send the results back to the master process, which finalizes the task. The traditional master-slave models introduce a bottleneck due to the master distributing tasks. Our approach eliminates this step and improves efficiency. We decided to let each process (slaves and master) generate starting points independently and send back the generated chains to the master process, which decides whether to accept a chain or reject it depending on whether a chain with the same endpoint exists in the table. This is done by utilizing a set data structure that handles duplicates. This is done in order to get a clean rainbow table, which is a table without merged chains. It is important to note that the generated table is not a perfect table; the imperfection comes from the lack of a chain regeneration mechanism for rejected chains. This design choice helps not only to simplify the handling of merged chains but also to reduce the number of point-to-point communications, which can have a significant influence on the execution time, speedup and efficiency of the parallel implementation.

By allowing each process to generate starting points independently, the workload is naturally distributed among all nodes, ensuring even computational distribution. This approach eliminates the risk of any single process becoming a bottleneck, leading to more efficient scaling as additional nodes are introduced. We emphasize that our implementation is designed to reduce the impact of network latency by decreasing the number of small messages being sent and eliminating the unnecessary communications.

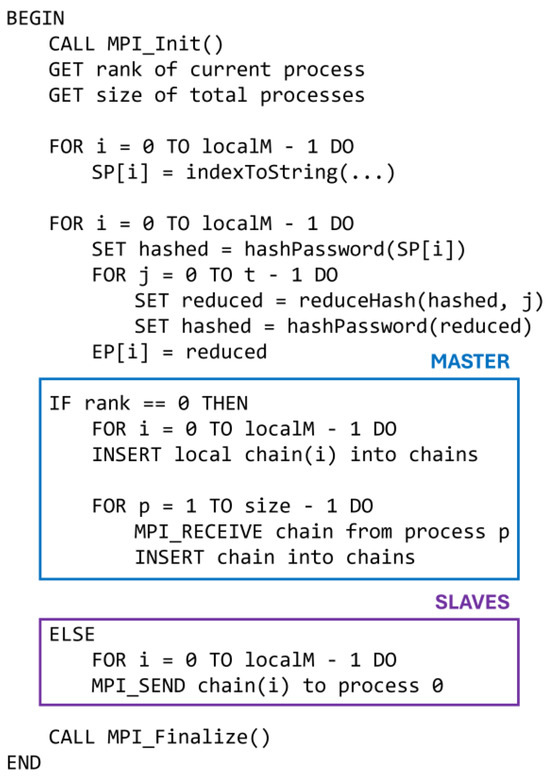

Figure 1 depicts a visual pseudocode of the proposed implementation. The light blue frame highlights the portion of the code that is executed by the master process, and the purple frame highlights the portion of the code that is executed by the slave processes.

Figure 1.

Visual pseudocode for the implementation of the parallel rainbow table generation.

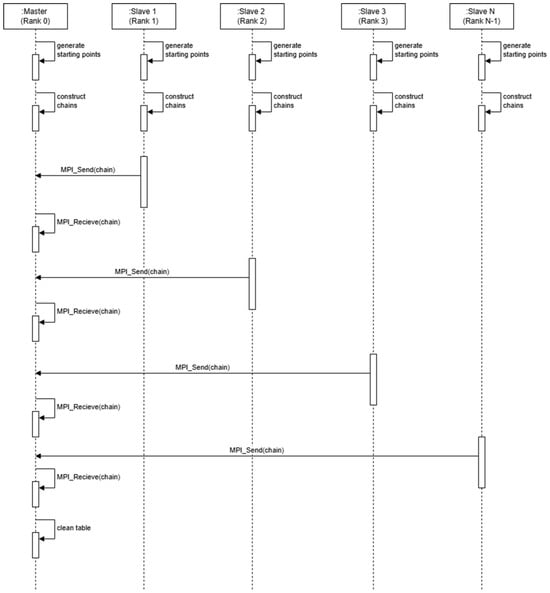

Figure 2 illustrates the parallel computing workflow using MPI for the proposed modified master-slave architecture. The sequence diagram depicts the interactions between a master process (rank 0) and multiple slave processes (rank 1 to rank N−1). Each lifeline in the sequence diagram represents an MPI process that performs the starting and endpoints generation. The program begins by initializing the MPI environment with MPI_Init(), where each process retrieves its rank and the total number of processes. Each process independently generates a subset of start points (SP) by converting indices into string representations and computes hash chains locally. For each starting point, the chain is computed by repeatedly applying a hash function followed by a reduction function, with the final reduced value stored as the endpoint (EP). The master process (rank 0) aggregates all chains by inserting its locally computed chains into a collection and receiving chains from all other processes via MPI_RECEIVE, while slave processes (rank > 0) send their locally computed chains to the master using MPI_SEND. This parallelization ensures that the workload is distributed evenly across processes, significantly reducing the time required to generate rainbow tables for modern hash functions. The program terminates by finalizing the MPI environment with MPI_Finalize().

Figure 2.

UML sequence diagram for the MPI-based proposed implementation.

4. Results and Discussion

In this section, we will present the results of a series of experiments to evaluate the performance of the proposed implementation and compare them to the results from three other researchers [10,37,38]. The experiments were executed on a dedicated cluster located in Vilnius Gediminas Technical University consisting of 15 nodes with 12th Gen Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-12700 processor (12 cores) with 16 GB RAM and Crypto++ version 8.9.0 installed to support cryptographic hash functions. We used three metrics for the performance evaluation: the first is the execution time, the second is the speedup calculated as the ratio between the execution time on a single processor and the execution time on p processors and the third metric is the efficiency calculated as a proportion of the speedup and number of computing nodes. The formulas for both speedup and efficiency are presented in Equation (1) and Equation (2), respectively. Both speedup and efficiency are unitless quantities; the speedup indicates how fast the program runs on p processes compared to a single process, while the efficiency represents how effectively multiple processors are utilized. This value is typically in the range from 0 to 1 and is presented in percentages in this paper.

4.1. The Influence of Hash Functions on the Parallel Performance

In the first experiment, rainbow tables were generated for four different cryptographic hash functions. We chose to use SHA-256, SHA-512, MD5 and NTLMv2 for this experiment. MD5 was once widely used as a cryptographic hash function. However, it has been discovered to have many vulnerabilities, and similarly, NTLM, which is based on outdated cryptographic schemes, is considered weak as well, and even Microsoft recommends transitioning to more modern authentication schemes like Kerberos or Negotiation authentication. Despite their obsolescence, MD5 and NTLMv2 are still found in legacy systems and are occasionally encountered in real-world scenarios, particularly during forensic analysis or penetration testing, as well as for backward compatibility with older systems and servers [41]. In addition, the majority of the business systems in recent years are legacy applications. Recent statistics show that more than 60% of the budget in IT organizations is spent on maintaining these legacy systems [42], and those systems still use those outdated cryptographic hash functions. Therefore, these algorithms are included in this experiment to provide a benchmark for evaluating the effectiveness and performance of attacks against known weak hash functions.

We generated a rainbow table for each of the above-mentioned hash functions for two cases of rainbow tables sizes, one with 10,000 processed chains, each containing 20,000 entries, and another one with 50,000 chains, each containing 40,000 entries. The generated tables were designed for passwords consisting of a minimum of one character and a maximum of five characters. The reason for the small input set is due to the limitations in the number of available resources. The charset used includes lowercase letters (26) and numbers (10) forming a set of 36 characters. This, combined with the range of password length, results in a search space with 62,193,780 combinations. To calculate the number of combinations in the search space, the permutations with repetition formula, shown in Equation (3), was used.

where is the number of options for each character in the password (36 in this case), and is the length of the password (from one to five characters). To get the total number of combinations, we need to add up all the values for each length, as shown in Equation (4).

The specific dimensions for the table were selected to evaluate the performance and scalability of the MPI-based implementation under varying workloads considering the imposed resources limitations. The two configurations provide a basis for analyzing how table size and chain length affect parallel execution efficiency and resource utilization.

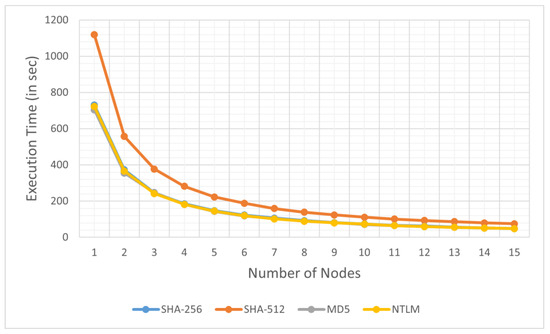

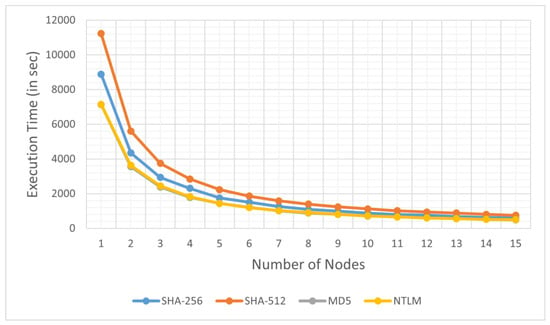

The results of this experiment are divided in two parts. The results of the first part of the experiment are presented in Figure 3 and Figure 4, which illustrate the execution times for generating rainbow tables using four cryptographic hash functions, SHA-256, SHA-512, MD5 and NTLMv2, across an increasing number of processing nodes in an MPI environment, starting from one node and incrementing by one until 15 nodes are reached, which is the maximum number of computing nodes in our experimental environment. The x-axis represents the number of nodes (ranging from 1 to 15), while the y-axis shows the execution time in seconds.

Figure 3.

Execution time for parallel medium-size rainbow tables generation for SHA-256, SHA-512, MD5 and NTLM (NTLMv2) cryptographic hash functions across an increasing number of computing nodes. The lines for SHA-256, MD5 and NTLM overlap due to the relatively small table dimensions.

Figure 4.

Execution time for parallel large-size rainbow tables generation for SHA-256, SHA-512, MD5 and NTLM (NTLMv2) cryptographic hash functions across an increasing number of computing nodes. The lines for MD5 and NTLM overlap due to the similarities between the internal characteristics of both hash functions.

Figure 3 presents the results for a 10,000-by-20,000 table, while Figure 4 presents the results for a 50,000-by-40,000 table. As depicted in both figures, the execution time decreases significantly with an increasing number of nodes, highlighting the efficiency of parallel computing in reducing computational overhead. Among the hash functions, SHA-512 has the highest execution time (1119 s for medium table and 11,229 s for large table) with a single node, followed by SHA-256 (730 s for medium table and 8888 s for large table), MD5 (704 s for medium table and 7134 s for large table) and NTLMv2 (722 s for medium table and 7148 s for large table). However, as the number of nodes increases, the execution time difference between the hash functions decreases, with all four functions converging to similar execution times beyond 10 nodes.

The cryptographic hash functions, SHA-256, MD5 and NTLMv2, have similar execution times in Figure 3, and they remain similar as the number of nodes increases and show no significant difference. As seen in Figure 4, this difference becomes more significant as the table dimensions increase, but there is still no significant difference between MD5 and NTLMv2 because NTLMv2 uses MD4 internally, which is similar to MD5 with very minor changes. As a result, the lines for NTLMv2 and MD5 overlap in the figures.

The second part of the experiment focuses on the speedup gained from the proposed implementation. The findings from this part of the experiment are shown in Table 1 and Table 2, which illustrate the speedup gains achieved by parallelizing rainbow table generation for the four previously mentioned cryptographic hash functions.

Table 1.

Speedup for parallel medium-size rainbow tables generation for SHA-256, SHA-512, MD5 and NTLMv2 cryptographic hash functions across an increasing number of computing nodes.

Table 2.

Speedup for parallel large-size rainbow tables generation for SHA-256, SHA-512, MD5 and NTLMv2 cryptographic hash functions across an increasing number of computing nodes.

In an ideal case, the speedup would be represented as a straight line, indicating that with p processes, we can achieve p times faster generation process. In our case, we did not achieve a perfectly linear speedup, but it is remarkably close to this ideal speedup, a scenario known as near-linear speedup. The tables demonstrate that the speedup achieved for all hash functions closely follows the ideal linear trend, indicating efficient utilization of computational resources in the parallel environment. This consistent performance across hash functions highlights the scalability and effectiveness of the parallel implementation, even for computationally intensive functions like SHA-512. We can also report that the efficiency is good as well and remains within the range of 95–99%.

These results indicate that the parallel computing approach using MPI achieves near-linear speedup, regardless of the computational complexity of the hash function and the table dimensions.

4.2. The Influence of Chain Count on the Execution Time

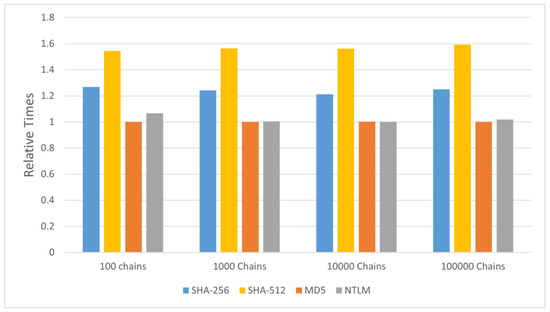

In the second experiment, we tested the scalability of our parallel implementation when the number of chains being processed is increasing. This experiment was executed for the same four cryptographic hash functions that were mentioned in Section 4.1; those hash functions are SHA-256, SHA-512, MD5 and NTLMv2. The implementation was executed on 15 computing nodes, and the execution times were measured for processing 100, 1000, 10,000 and 100,000 chains while keeping the chain length constant at 10,000. Those values were chosen to evaluate the scalability of the parallel implementation against different table sizes.

The results of this experiment are presented in Figure 5, which illustrates the relative execution times for generating rainbow tables using four cryptographic hash functions, SHA-256, SHA-512, MD5 and NTLMv2, with varying counts of chains. The values shown in the figure are relative to the fastest algorithm in each group. The x-axis represents the number of chains, while the y-axis shows the relative execution time. As shown in the figure, SHA-512 consistently exhibits the highest relative execution time, reflecting its greater computational complexity, while MD5 and NTLMv2 perform much faster, as expected due to their algorithmic weaknesses. SHA-256 occupies the middle ground.

Figure 5.

Relative execution time for parallel rainbow tables generation with varying chain counts and 15 computing nodes for SHA-256, SHA-512, MD5 and NTLM (NTLMv2) cryptographic hash functions (the values are relative to the fastest algorithm in each group).

4.3. The Influence of Chain Length on the Execution Time

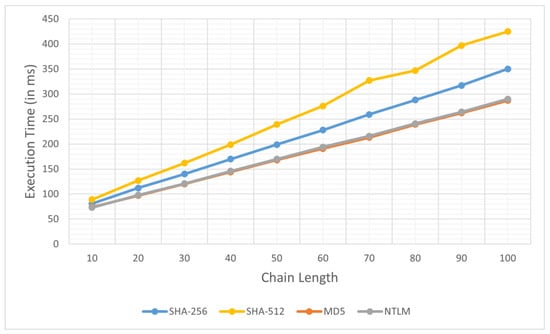

In the third experiment, we evaluated the performance of our implementation when increasing the length of the generated chains. This experiment was executed for the same four cryptographic hash functions as mentioned in the previous subsections. The implementation was executed on 15 computing nodes and with 10,000 processed chains.

The execution times were measured for chains of length 10 until 100, increasing the length by a factor of 10 for each step. Those values were chosen to evaluate the scalability of the parallel implementation against different table sizes.

Figure 6 presents the results of this experiment, where each line represents a different hash function. In this figure, the x-axis represents the chain length, and the y-axis represents the execution time in milliseconds. Looking at the figure, we can make a few observations that can give us some information on the relationship between chain length and execution time.

Figure 6.

Execution time for parallel rainbow tables generation with varying chain lengths and 15 computing nodes for SHA-256, SHA-512, MD5 and NTLM (NTLMv2) cryptographic hash functions.

First, we can notice that as the chain length increases, the execution time for all four hash functions also increases. However, the rate of increase differs from one hash function to another. SHA-512 exhibits the steepest slope, indicating a higher computational cost compared to the other hash functions. MD5, on the other hand, has the shallowest slope, suggesting the lowest computational overhead. The execution times for SHA-256 and NTLMv2 fall between those of SHA-512 and MD5, with NTLMv2 consistently below SHA-256 across all chain lengths.

The second observation is related to the similarity between MD5 and NTLMv2, which indicates that their internal implementation is similar. In fact, NTLMv2 uses the MD4 hash function, which has similar structure, operates on the same size blocks, and produces a digest of the same size as MD5. This similarity is significant because it tells us that NTLMv2 inherits structural weaknesses from MD4 and MD5, both of which have known cryptographic vulnerabilities.

4.4. The Impact of the Internal Characteristics of the Cryptographic Hash Functions on the Performance of Parallel Rainbow Tables Generation

Cryptographic hash functions are designed to transform a message into a fixed-length digest using a series of mathematical operations. Their internal characteristics include digest size, block size and number of rounds. These characteristics determine their computational efficiency, security and suitability for different applications. Each hash function differs by the block size it operates on and the number of rounds it performs.

The digest size determines the length of the hash output, affecting security against collision attacks. Larger digest sizes, such as the 512-bit output of SHA-512, provide enhanced resistance, while smaller digest sizes, like the 128-bit outputs of MD5 and NTLMv2, are more vulnerable to cryptographic attacks.

The block size defines the amount of data processed per round. SHA-512 operates on 1024-bit blocks, whereas SHA-256 and MD5 use 512-bit blocks. Larger block sizes demand more computational resources but offer increased resistance to attacks. NTLMv2, derived from MD4, does not follow the same structured block-processing approach, further reducing its security.

The number of rounds impacts both security and execution time. SHA-512 performs 80 rounds of computations, significantly more than the 64 rounds of SHA-256, increasing its computational workload. MD5 and SHA-256 also utilize 64 rounds, whereas NTLMv2, with only three rounds, is computationally lightweight but highly insecure.

The impact of these characteristics is evident in the results obtained from the experiments. Table 3 summarizes the internal characteristics of the cryptographic hash functions examined in this study. During our experiments, SHA-512 demonstrated the highest execution time due to its increased number of rounds and larger block size, making it computationally intensive. In contrast, MD5 and NTLMv2 exhibited the lowest execution times, due to their smaller block sizes, fewer rounds and simpler computational structures. These factors directly affect execution time, as hash functions with greater complexity require more processing cycles. The increased number of computational steps, such as additional rounds and larger block sizes, results in higher memory and CPU utilization, leading to longer processing times.

Table 3.

Summary of cryptographic hash functions internal characteristics.

The trade-off between security and performance is evident: SHA-512 offers superior cryptographic strength at the cost of higher computational demands, while MD5 and NTLMv2 provide faster processing speeds but lack security resilience.

4.5. Comparative Analysis

In our proposed parallel implementation, we chose to utilize the master-slave approach with our proposed modification using the Message Passing Interface standard to improve the performance of rainbow tables generation. The classic master-slave approach relies on the master process to generate tasks and distribute them among the slave processes. As the distribution of tasks requires communications between processes, which contributes to the execution time, we gave each process, including the master process, the responsibility of generating the tasks (generate starting points for rainbow chains) for themselves, which reduces the amount of communications between processes and, as a result, improves the performance of the implementation.

In this section, we aim to compare our results to three other MPI-based implementations from Sykes et al. [37], Al-Khazraji [10] and Avoine et al. [38], who used MPI to speed up the rainbow tables generation. The first two implementations are quite old, but they still present questions relevant to modern computing.

Each implementation, including the approach in this paper, differs in the problem being solved. Sykes et al. [37] focused on improving the RainbowCrack tool for rainbow tables attack, essentially targeting the long time required to generate rainbow tables as well as to search them. Al-Khazraji [10] focused solely on the long time required to generate rainbow tables, and Avoine et al. [38] aimed at solving the problem of inefficiency related with discarding merged chains during the generation process.

In terms of the parallelization model, only Al-Khazraji [10] explicitly mentioned the parallelization model (classic master-slave). Our method improves on this model by decentralizing the chains generation to each process (modified master-slave).

Looking at the number of computing nodes (or CPU cores), we can see significant differences. Al-Khazraji [10] was the one utilizing the largest amount of computing nodes (exactly 201 nodes), while Avoine et al. [38] utilized the least amount of nodes, equalling five. Our experimental environment consists of 15 CPU nodes. Although the more resources one has the better, it is not always feasible.

In terms of performance, Al-Khazraji [10] achieved the largest performance gain due to the size of the cluster used in his experiments. He reduced the generation time from 816.62 min in sequential implementation to 3.38 min in parallel implementation and reduced the generation time from 7.14 days in sequential implementation to 46.45 min in parallel implementation. His results were measured for generation of a rainbow table consisting of 10,000,000 chains and 100,000,000 chains, respectively, when using 201 computing nodes, one for the master process and 200 for the slave processes. In our case, we are limited with the number of computing nodes; we utilized exactly 15 nodes in our experimental environment. Generating a rainbow table with dimensions close to 10,000,000 chains takes 41.73 min, which is less then it took to generate 100,000,000 chains with the author’s parallel implementation.

Sykes et al. [37] also achieved some performance gain reducing the execution time from an estimated six years to just a few days. This result demonstrates a significant increase in efficiency, indicating the potential of their optimizations or architectural changes in resolving the scalability issues of the original solution. Despite this improvement, the execution time still has practical limitations. In real-world scenarios, particularly those involving iterative development, frequent updates, or time-sensitive analysis, a several-day wait time may be considered excessive.

In contrast, Avoine et al. [38] achieved a 2.56 speedup factor when employing a multicore processing configuration with five CPU cores on a standard personal computer. While this result implies an acceptable level of parallel efficiency, it also highlights limitations in scalability and parallel job distribution. This result shows that the algorithm’s intrinsic serial components limit its capacity to scale efficiently over several cores. Furthermore, the utilization of only five cores, while feasible for a consumer-grade setup, raises the question of how well the approach would function on systems with more parallel capacity.

A key factor influencing the performance of MPI-based implementations is the number of communications required, which is directly dependent on the number of processed chains, as each process generates chains independently, unlike the referenced paper’s [10] approach. In the referenced implementation, there are additional communications related with tasks distribution, which are eliminated in our proposed implementation. Our approach eliminates this communication overhead by avoiding explicit task distribution and as a result reduces the bottleneck in the master process.

This comparison highlights the importance of efficient process management and communication strategies in parallel computing. Our results confirm that a carefully designed parallel implementation can deliver excellent performance, even in environments with limited computational resources. In Table 4, we present the summary of the comparative analysis, covering six aspects of all implementations. Those aspects include the problem addressed in each paper, the parallelization model, number of computing nodes (or CPU cores) used for execution of experiments, performance improvement as reported in the respective papers, execution time and the strategy to handle chain merges.

Table 4.

Summary of comparative analysis.

5. Limitations and Future Work

A few limitations were identified during the course of this research. One key constraint was the limited number of computing nodes available in our experimental environment, which restricted the scale of our implementation compared to other studies. Testing the implementation on bigger clusters would be necessary. Another limitation is the lack of a chain regeneration mechanism, which is tricky to implement in a distributed memory environment. This absence led to fewer generated chains then requested, which makes the table imperfect. Future work could address this issue and improve the rainbow table generation process. Another area for future work is to experiment with other parallelization techniques for rainbow tables generation, for example, utilizing the power of GPU to enhance the generation process.

6. Conclusions

This research presents an approach to the parallel generation of rainbow tables using the Message Passing Interface standard. The proposed approach is based on a modified master-slave model, where each process independently generates starting points, and the master process resolves chain conflicts. Our implementation achieves significant improvements in performance and efficiency. The reduction in inter-process communication compared to traditional approaches enhances scalability and execution speed, as demonstrated through experimental evaluations. The experimental evaluation is composed of three experiments. In the first experiment, we evaluated the parallel performance for four cryptographic hash functions (SHA-256, SHA-512, MD5 and NTLMv2), achieving near-linear speedup and maintaining efficiency between 95% and 99% across different numbers of computing nodes. This demonstrates the scalability and robustness of the implementation, even for computationally demanding functions like SHA-512.

The second experiment highlighted the scalability of the implementation by varying the number of processed chains from 100 to 100,000. The results revealed that the execution time increases with larger workloads, with SHA-512 exhibiting the highest computational cost due to its complexity. In the third experiment, we analyzed the influence of chain length on execution time. The findings showed that longer chains significantly increased execution times, with SHA-512 once again showing the steepest growth, while MD5 and NTLMv2 had relatively lower computational overhead.

In addition, the study acknowledges certain limitations, including the absence of a chain regeneration mechanism and constraints imposed by the available computing infrastructure. It is important to note that our implementation could be extended to longer and more complex passwords by adjusting the reduction function and search space size. Obviously, this would require additional computational resources due to the exponential increase of the search space. Overall, the proposed approach contributes a practical and efficient solution to the computational demands of rainbow table generation, advancing the field of cryptanalysis and password recovery.

While the use of password salting has significantly reduced the effectiveness of rainbow tables in modern authentication systems, our work remains relevant in scenarios where salting is absent or improperly implemented or when legacy systems are targeted. In addition, the use of rainbow tables can be useful for penetration testing, cyber forensics investigations and password security evaluations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.V., N.G. and A.K.; methodology, M.V., N.G. and A.K.; software, M.V.; formal analysis, M.V.; investigation, M.V. and A.K.; supervision, A.K. and N.G.; writing—original draft preparation, M.V.; writing—review and editing, M.V., N.G. and A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in a publicly accessible repository. The original data presented in the study are openly available in GitHub at https://github.com/markvnr/MPI-RainbowTables-Experiment-Data/ (accessed 18 February 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bonneau, J.; Herley, C.; Van Oorschot, P.C.; Stajano, F. The Quest to Replace Passwords: A Framework for Comparative Evaluation of Web Authentication Schemes. In Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, San Francisco, CA, USA, 20–23 May 2012; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 553–567. [Google Scholar]

- Menezes, A.J.; Vanstone, S.A.; Van Oorschot, P.C. Handbook of Applied Cryptography, 1st ed.; CRC Press, Inc.: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1996; ISBN 0849385237. [Google Scholar]

- Horálek, J.; Holík, F.; Horák, O.; Petr, L.; Sobeslav, V. Analysis of the Use of Rainbow Tables to Break Hash. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2016, 32, 1523–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosnjak, L.; Sres, J.; Brumen, B. Brute-Force and Dictionary Attack on Hashed Real-World Passwords. In Proceedings of the 2018 41st International Convention on Information and Communication Technology, Electronics and Microelectronics, MIPRO 2018—Proceedings, Opatija, Croatia, 21–25 May 2018; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1161–1166. [Google Scholar]

- Delaune, S.; Jacquemard, F. A Theory of Dictionary Attacks and Its Complexity. In Proceedings of the Computer Security Foundations Workshop, Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 30 June 2004; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2004; Volume 17, pp. 2–15. [Google Scholar]

- Oechslin, P. Making a Faster Cryptanalytic Time-Memory Trade-Off. In Advances in Cryptology—CRYPTO 2003; LNCS; Boneh, D., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; Volume 2729, pp. 617–630. [Google Scholar]

- Hellman, M. A Cryptanalytic Time-Memory Trade-Off. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1980, 26, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kačeniauskas, A.; Rutschmann, P. Parallel FEM Software for CFD Problems. Informatica 2004, 15, 363–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kačeniauskas, A.; Kačianauskas, R.; Maknickas, A.; Markauskas, D. Computation and Visualization of Discrete Particle Systems on GLite-Based Grid. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2011, 42, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khazraji, S.H.A.A. Using Parallel Computing to Implement Security Attack. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Inf. Secur. 2015, 13, 35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Meganathan, N. What Is the Effectiveness of Salt and Pepper in Preventing Rainbow Table Attacks in Modern Password Hashing Algorithms? Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Technol. 2024, 9, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosaaen, K. LM Hash Cracking—Rainbow Tables vs GPU Brute Force. Available online: https://www.netspi.com/blog/technical-blog/network-pentesting/lm-hash-cracking-rainbow-tables-vs-gpu-brute-force/ (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Pabico, J.P. A Framework for a Multiagent-Based Scheduling of Parallel Jobs. arXiv 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borisenko, A.B.; Gorlatch, S. Parallel MPI-Implementation of the Branch-and-Bound Algorithm for Optimal Selection of Production Equipment. Bull. Tambov. State Tech. Univ. 2016, 22, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, H. Hans Peter Luhn and the Birth of the Hashing Algorithm. Available online: https://spectrum.ieee.org/hans-peter-luhn-and-the-birth-of-the-hashing-algorithm (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- Pacevič, R.; Kačeniauskas, A. Hash Functions and GPU Algorithm of Infinite Grid Method for Contact Search. Inf. Technol. Control 2022, 51, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Liu, Z.; Tong, R.; Manocha, D. PSCC: Parallel Self-Collision Culling with Spatial Hashing on GPUs. Proc. ACM Comput. Graph. Interact. Tech. 2018, 1, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Feng, D.; Lai, X.; Yu, H. Collisions for Hash Functions MD4, MD5, HAVAL-128 and RIPEMD. Cryptol. ePrint Arch. 2004, 2004/199. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, M.; Sotirov, A.; Appelbaum, J.; Lenstra, A.; Molnar, D.; Osvik, D.A.; de Weger, B. Short Chosen-Prefix Collisions for MD5 and the Creation of a Rogue CA Certificate. In Advances in Cryptology—CRYPTO 2009; LNCS; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; Volume 5677, pp. 55–69. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, T.; Liu, F.; Feng, D. Fast Collision Attack on MD5. Cryptol. ePrint Arch. 2013, 2013/170. [Google Scholar]

- Nkouankou, A.; Clarice, F.; Abel, W.; Ndoundam, R. Pre-Image Attack of the MD5 Hash Function by Proportional Logic. Int. J. Res. Innov. Appl. Sci. 2022, 7, 2454–6194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Lai, X. Preimage Attacks on Reduced DHA-256. Cryptol. ePrint Arch. 2009, 2009/552. [Google Scholar]

- Dobbertin, H. The First Two Rounds of MD4 Are Not One-Way. In Fast Software Encryption; LNCS; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1998; Volume 1372, pp. 284–292. [Google Scholar]

- Kelsey, J.; Schneier, B. Second Preimages on N-Bit Hash Functions for Much Less than 2n Work. In Advances in Cryptology—EUROCRYPT 2005; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; Volume 3494, pp. 474–490. [Google Scholar]

- Sulak, F.; Koçak, O.; Saygı, E.; Öğünç, M.; Bozdemır, B. A Second Pre-Image Attack and a Collision Attack to Cryptographic Hash Function Lux. Commun. Fac. Sci. Univ. Ank. Ser. A1 Math. Stat. 2017, 66, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreeva, E.; Bouillaguet, C.; Dunkelman, O.; Fouque, P.-A.; Hoch, J.; Kelsey, J.; Shamir, A.; Zimmer, S. New Second-Preimage Attacks on Hash Functions. J. Cryptol. 2016, 29, 657–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, D. Cryptography and Data Security; Addison-Wesley Longman Publishing Co., Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 1982; ISBN 0201101505. [Google Scholar]

- Avoine, G.; Junod, P.; Oechslin, P. Characterization and Improvement of Time-Memory Trade-Off Based on Perfect Tables. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. Secur. 2008, 11, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avoine, G.; Carpent, X. Optimal Storage for Rainbow Tables. In Proceedings of the Information Security and Cryptology—ICISC 2013, LNCS, Seoul, Korea, 27–29 November 2013; Lee, H.-S., Dong-Guk, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; Volume 8565, pp. 144–157. [Google Scholar]

- Quan, L.J.; Ye, T.J.; Ling, G.G.; Balachandran, V. QIris: Quantum Implementation of Rainbow Table Attacks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.07032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dat, T.N.; Iwai, K.; Matsubara, T.; Kurokawa, T. Implementation of High Speed Rainbow Table Generation Using Keccak Hashing Algorithm on GPU. In Proceedings of the 2019 6th NAFOSTED Conference on Information and Computer Science (NICS), Hanoi, Vietnam, 12–13 December 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 166–171. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.W.; Seo, J.; Hong, J.; Park, K.; Kim, S. High-speed Parallel Implementations of the Rainbow Method Based on Perfect Tables in a Heterogeneous System. Softw. Pract. Exp. 2015, 45, 837–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhu, W.; Chen, J.; Yao, S.; Hsu, C.F.; Xiong, G. High-Speed Implementation of Rainbow Table Method on Heterogeneous Multi-Device Architecture. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2023, 143, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalenderi, M.; Pnevmatikatos, D.; Papaefstathiou, I.; Manifavas, C. Breaking the GSM A5/1 Cryptography Algorithm with Rainbow Tables and High-End FPGAS. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Field Programmable Logic and Applications (FPL), Oslo, Norway, 29–31 August 2012; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 747–753. [Google Scholar]

- Papantonakis, P.; Pnevmatikatos, D.; Papaefstathiou, I.; Manifavas, C. Fast, FPGA-Based Rainbow Table Creation for Attacking Encrypted Mobile Communications. In Proceedings of the 2013 23rd International Conference on Field programmable Logic and Applications, Porto, Portugal, 2–4 September 2013; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Theocharoulis, K.; Papaefstathiou, I.; Manifavas, C. Implementing Rainbow Tables in High-End FPGAs for Super-Fast Password Cracking. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on Field Programmable Logic and Applications, Milan, Italy, 31 August–2 September 2010; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 145–150. [Google Scholar]

- Sykes, E.R.; Skoczen, W. An Improved Parallel Implementation of RainbowCrack Using MPI. J. Comput. Sci. 2014, 5, 536–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avoine, G.; Carpent, X.; Leblanc-Albarel, D. Stairway to Rainbow. In Proceedings of the ACM Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 10–14 July 2023; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 286–299. [Google Scholar]

- Avoine, G.; Carpent, X.; Leblanc-Albarel, D. Precomputation for Rainbow Tables Has Never Been so Fast. In Proceedings of the 26th European Symposium on Research in Computer Security, Darmstadt, Germany, 4–8 October 2021; pp. 215–234. [Google Scholar]

- Westergaard Jørgensen, M. Free Rainbow Tables: Distributed Rainbow Table Project. Available online: https://freerainbowtables.com/ (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- Vaideeswaran, N. NTLM Explained. Available online: https://www.crowdstrike.com/en-us/cybersecurity-101/identity-protection/windows-ntlm/ (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Adusumilli, S. Testing a Legacy Application with Zero Documentation. Available online: https://www.cigniti.com/blog/testing-a-legacy-application-with-zero-documentation/ (accessed on 26 June 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).