Abstract

The psychological readiness of athletes and its connection to their functional status in returning to sport after a musculoskeletal injury has been previously studied. The “Psychological Readiness of Injured Athlete to Return to Sport” (PRIA-RS) questionnaire is a widely used tool designed to assess an athlete’s psychological readiness to return to sport. The purpose of the present study is to investigate the validity and reliability of the PRIA-RS questionnaire in Greek football athletes. The questionnaire was administered to 113 football athletes, and its face validity, content validity, concurrent validity, construct validity, test–retest reliability, and internal consistency were assessed. The face and content validity of the PRIA-RS were supported, and an exploratory factor analysis confirmed the instrument’s original two-factor structure. Its concurrent validity was demonstrated by examining correlations between the PRIA-RS and three other measures: the Causes of Re-Injury Worry Questionnaire, the Sport Confidence Questionnaire for Rehabilitated Athletes Returning to Competition, and the Attention Questionnaire for Rehabilitated Athletes Returning to Competition. The PRIA-RS exhibited a good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.82). The intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) for the test–retest reliability of each factor were excellent (ICC = 0.97−0.99). Overall, the PRIA-RS appears to be a valid and reliable tool that rehabilitation professionals can utilize in both clinical practice and research by realizing the athletes’ psychological needs and helping them to return safer with no future musculoskeletal injuries.

1. Introduction

A sporting event leading to a musculoskeletal injury is highly prevalent among the athletic population today, as the number of individuals participating in sports has rapidly increased [1,2]. The intense demands placed on athletes in sports are associated with a heightened risk of injury [2]. The Sports and Fitness Industry Association’s 2022 report highlighted a rise in musculoskeletal injuries among the athletic population in the USA [1].

It is well known that musculoskeletal injuries often result in the absence of players during the competition season [2]. According to a systematic review by Ryan et al. [3], soccer is the most popular sport across all age groups and regions. However, a descriptive analysis by Bueno et al. [4] reported that soccer is characterized by a high prevalence of injuries. A recent meta-analysis by López-Valenciano et al. [5] reported an injury rate of 8.1 per 1000 h of exposure among professional soccer players, while in Greece, the injury incidence was 55 injuries per 1000 match-playing exposure hours at the same competition level [6]. Notably, previous studies have shown that 25–30% of these injuries are classified as recurrences, emphasizing that the impact of soccer injuries extends beyond the initial incident [7]. In fact, symptoms resulting from a secondary injury event have been shown to be worse than those from the primary injury [8]. Therefore, prioritizing the quality of the recovery process and avoiding hasty return-to-sport (RTS) decisions is crucial to reducing the likelihood of re-injury in soccer [9].

Sports injuries not only impair functional mobility, but also generate psychological disruptions, which can affect the duration and efficacy of the rehabilitation program [10]. Wiese-Bjornstal et al. [11], in developing the model of athletes’ responses to sports injuries, highlighted that psychological reactions to injury incidents vary among athletes due to personal factors (e.g., personality and motivation) and situational factors (e.g., external support and rehabilitation environment). Both positive and negative psychological responses—such as stress, anxiety, fear of re-injury, confidence, motivation, and attention—play a crucial role in the athlete’s rehabilitation process [12,13,14]. These psychological factors are not only critical to the rehabilitation journey but also help explain why some individuals are able to successfully return to their pre-competition performance levels while others struggle to do so [15].

While an athlete’s psychological reactions may evolve over the course of rehabilitation, several studies indicate that negative psychological responses often intensify as the athlete prepares to return to sport (RTS) following a musculoskeletal injury [16,17]. Psychological preparedness consists of three key components: (a) confidence in resuming athletic activities, (b) realistic expectations for athletic performance, and (c) personal motivation to return to pre-injury levels [18,19]. To regain their prior physical performance levels, athletes must achieve both psychological and functional readiness. Research has shown that 65% of athletes who do not return to sport cite psychological challenges as the primary reason, with the fear of re-injury being the most significant barrier to resuming competition [20,21].

Poor psychological preparedness during the RTS phase not only negatively impacts the quality of the athlete’s performance but also increases the risk of re-injury upon returning to sport [22]. When returning to the field, athletes may worry about their physical condition and overthink the execution of skills, which can further increase the risk of re-injury [10,23]. Ardern et al. [24] highlighted the importance of ensuring that injured athletes can safely return to competition. Regular evaluations throughout the rehabilitation process, particularly during the RTS phase, can help rehabilitation professionals identify maladaptive psychological responses [25].

Both physical and psychological RTS should be used to ensure a safe return, not just in training, but also in competition.

The Psychological Readiness of Injured Athlete to Return to Sport (PRIA-RS) questionnaire was developed by Gomez-Piqueras et al. [26] to assist clinicians in making decisions regarding a soccer player’s psychological readiness to return to training after injury. Previous psychological scales, such as the Injury Psychological Readiness to Return to Sport (I-PRRS) [27], Re-Injury Anxiety Inventory (RIAI) [28], and the Anterior Cruciate Ligament-Return to Sport after Injury (ACL-RSI) [29], have certain limitations as they assess only isolated aspects of psychological readiness to return to sport. Specifically, the I-PRRS consists of 6 items focused solely on self-confidence, the RIAI is composed of 28 items related to re-injury anxiety, and the ACL-RSI is injury-specific, as it was developed for anterior cruciate ligament injuries.

Gomez-Piqueras et al. [26] highlighted that rehabilitation professionals can use the PRIA-RS questionnaire to comprehensively assess an athlete’s psychological readiness for a return to sport (RTS). This tool evaluates factors such as confidence, personal perception, insecurity, and fear of re-injury at the end of the recovery process. The psychometric reliability and effectiveness of the PRIA-RS in measuring the psychological readiness for the RTS were further validated by Gomez-Piqueras et al. [9]. They concluded that (a) the tool is considered valid for determining the psychological readiness of a professional soccer player on the day before returning to practice after an injury, and (b) using the PRIA-RS questionnaire with soccer players could help prevent re-injury. However, none of the aforementioned instruments—i.e., I-PRRS, RIAI, and ACL-RSI—have been psychometrically evaluated to assess the psychological readiness to return to sport in Greek athletes. Only three valid questionnaires are available for assessing specific aspects of psychological readiness in Greek athletes: the “Causes of Re-Injury Worry Questionnaire” (CR-IWQ) [30], the “Sport Confidence Questionnaire of Rehabilitated Athletes Returning to Competition” (SCQ-RARC) [31], and the “Attention Questionnaire of Rehabilitated Athletes Returning to Competition” (AQ-RARC) [32]. The primary difference between the PRIA-RS and the other three questionnaires in Greek is that the PRIA-RS evaluates the psychological readiness for the RTS through a holistic approach, while the CR-IWQ focuses on re-injury worry, the SCQ-RARC assesses self-confidence, and the AQ-RARC measures competitive attention and its disruption. A valid and reliable instrument in Greek, such as the PRIA-RS, would further contribute to assessing an athlete’s psychological readiness to return to competitive activity after an injury. By using this questionnaire, rehabilitation professionals can also help reduce the likelihood of re-injury. Thus, the aim of the present study was to examine the psychometric properties of the PRIA-RS questionnaire in Greek football athletes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

The sample consisted of 143 male athletes who voluntarily participated in the study. The inclusion criteria for participants were as follows: (a) active male amateur athletes training at least 3 times per week for 2 h per session, (b) aged between 18 and 35 years, (c) having experienced an acute musculoskeletal injury within the last 6 months, (d) having a rest period due to the injury lasting from 15 days to 2 months, (e) full completion of the rehabilitation program for their injury, (f) being football players, and (g) having no previous surgeries on their limbs. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) injury to the opposite side, and (2) inability to understand the Greek language.

The initial translated version of the PRIA-RS was administered to 15 athletes to ensure it could be fully understood. The Greek version of the PRIA-RS was then administered to two sample groups. The first sample consisted of 30 participants (mean [SD] age = 26.48 [3.48] years), who contributed to the initial validation of the cross-culturally adapted version of the questionnaire and the assessment of its reliability. The second sample, which included 113 participants (mean [SD] age = 24.68 [3.94] years), was used to assess the construct and concurrent validity.

According to Hatcher et al. [33], the recommended minimum sample size for an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) is generally at least 5 cases per item, with 10 cases per item considered ideal. The PRIA-RS questionnaire consists of 10 items, so the minimum ideal sample size would be 100 cases.

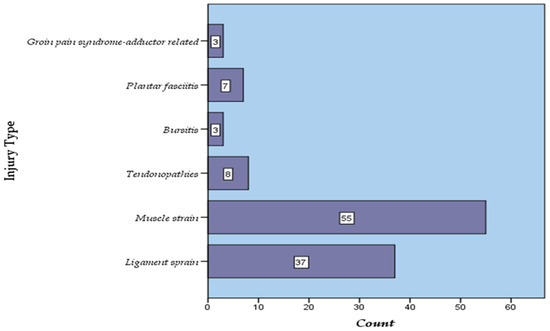

All 113 participants were male amateur football players. Of these, 40 (35%) competed in the third division (“C League”) of the local championship, 26 (23%) in the second division (“B League”), and 47 (42%) in the first division (“A League”). The mean competitive experience of the participants was 8.63 years (SD = 4.09). All athletes had sustained an acute musculoskeletal injury before completing the questionnaire, with a mean rest duration of 20.9 days (SD = 8.18). All injuries occurred in the lower extremities (Figure 1). The mean duration of physiotherapy treatment was 18.58 ± 8.81 days. All athletes had completed their rehabilitation programs and were ready to return to competition.

Figure 1.

The injury type of the sample.

This study was conducted following the ethical recommendations from the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by University’s Institutional Research Ethics Committee prior to data collection (5364/11 March 2024). Informed consent was obtained from all the athletes before participation.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographics

All participants completed a brief form that described their demographic and clinical characteristics, including their age, gender, and injury details (e.g., area, type, and days of absence). They also provided information about their physiotherapy (e.g., duration and frequency per week) and medical rehabilitation programs.

2.2.2. The Psychological Readiness of Injured Athlete to Return to Sport Questionnaire (PRIA-RS)

The PRIA-RS is a self-completed questionnaire, specifically a patient-reported outcomes (PROs) tool [34], consisting of 10 items [26]. Each item is assessed on a 5-point Likert scale, with a total possible score of 50 points. A higher score indicates a more favorable psychological response, with a cut-off of less than 40 total points suggesting a lower level of psychological readiness [9]. The PRIA-RS evaluates two factors: (a) “Insecurity, Self-confidence, and Individual Perception” and (b) “Fear of Re-injury”. A higher score on the first factor indicates a lower insecurity, higher self-confidence, and a more positive individual perception of the environment (score range 7–35), while a higher score on the second factor indicates a more positive mood, lower levels of anxiety, and absence of fear of re-injury (score range 3–15).

2.2.3. The Causes of Re-Injury Worry Questionnaire (CR-IWQ)

The CR-IWQ includes 12 questions and two factors:

- “Re-injury worry due to rehabilitation” (Cronbach’s α = 0.95, score range 8–56): higher scores indicate increased concern about re-injury due to poor rehabilitation programs;

- “Re-injury worry due to opponent’s ability” (Cronbach’s α = 0.93, score range 4–28): a higher score implies greater concern about re-injury due to the opponent’s ability [30].

2.2.4. The Sport Confidence Questionnaire of Rehabilitated Athletes Returning to Competition (SCQ-RARC)

The SCQ-RARC is comprised of 14 questions and two factors:

- “Confidence due to rehabilitation” (Cronbach’s α = 0.93, score range 8–56): a higher score means the athlete’s confidence has increased as a result of a successful rehabilitation program;

- “General confidence” (Cronbach’s α = 0.97, score range 6–42): a greater score indicates that the athlete feels more confident in their own capabilities [31].

2.2.5. The Attention Questionnaire of Rehabilitated Athletes Returning to Competition (AQ-RARC)

The AQ-RARC consists of 10 questions and 2 factors:

- “Functional attention” (Cronbach’s α = 0.97, score range 7–49): a higher score implies greater attention by the athlete;

- “Distraction attention” (Cronbach’s α = 0.94, score range 3–21): an athlete who scores higher is more easily distracted [32].

The three validated questionnaires in the Greek language (CR-IWQ, SCQ-RARC, and AQ-RARC) were also accessed in two other studies in order to evaluate the psychological readiness of the athletes in RTS phase and identify possible differences between the two genders [35,36].

2.3. Procedure

The athletes were contacted directly by the first and second authors, who collected the data and informed them about (a) the purpose of the study, (b) the voluntary nature of participation, and (c) the confidentiality of their responses. Any injured athlete who met the inclusion criteria and expressed an interest in participating in the study was asked to sign an informed consent form and complete the demographic questionnaire. The initial translated version of the PRIA-RS was administered to 15 athletes to ensure it was fully comprehensible. Athletes from the first sample group (n = 30) were then asked to complete the questionnaire twice, with an interval of 14 days, to determine the test–retest reliability. Athletes from the second sample group (n = 113) completed the PRIA-RS questionnaire, the CR-IWQ, the SCQ-RARC, and the AQ-RARC questionnaires. The completion of these instruments took approximately 20 min.

Validation Procedure

The study was conducted following the guidelines for the translation and cultural adaptation of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) as outlined in the ISPOR report—The Professional Society for Health Economics and Outcomes Research [37], along with the quality standards for the measurement properties of health status questionnaires [38]. The validation procedure consisted of 5 stages.

Stage 1: The PRIA-RS was forward-translated from English to Greek by two Greek physiotherapists who both spoke English fluently. According to the ISPOR rules [34], it is ideal that the forward translators are citizens of the target nation and have excellent knowledge of PRO measures interpretation. The first translator was acquainted with the objectives that the questionnaire had been developed to measure, in order for his translation to closely match the original instrument. The second translator, unaware of the questionnaire’s purpose, produced the second translation to highlight subtle differences between the two versions of the original questionnaire. Any inconsistencies between the two translators were then reviewed and resolved, resulting in a single translation version of the PRIA-RS.

Stage 2: A different translator, a native speaker of the original language (English) and proficient in the target language (Greek), with no prior experience with the original PRIA-RS, conducted a back translation of the first Greek version of the PRIA-RS. The initial two translators, along with the other authors and the back translator, assessed these translations to ensure conceptual equivalence between the original and the Greek versions;

Stage 3: a multilingual committee, consisting of the three translators, the two remaining authors, and one methodologist, reached a consensus on an acceptable pre-final version of the PRIA-RS in Greek by comparing all translations with the original version;

Stage 4: The pre-final version of the PRIA-RS was initially distributed to a group of 30 volunteers to ensure its clarity. The volunteers were asked in person whether they fully understood the scale. These individuals met the same inclusion criteria as the study’s main sample. Based on their feedback, several adjustments were made to the instrument’s language, syntax, and overall comprehension;

Stage 5: The final version of the PRIA-RS, along with the other three valid questionnaires, was administered to 113 volunteers. The researchers provided instructions and clarifications as needed while monitoring the correct completion of the questionnaires (Appendix A).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS; Version 28.00). A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Descriptive statistics are presented as the means (M), standard deviations (SD), and frequencies (f) for patients’ demographic characteristics. Kolmogorov–Smirnov normality tests were conducted to assess the normality of the data. Based on these results, Spearman’s rank correlations were used to assess the concurrent validity by correlating the PRIA-RS factors with those of the other three constructs.

The face validity was examined by the first group of 30 patients, who provided feedback on whether the questionnaire items appeared valid and seemed to reflect a good translation of the construct. The content validity was assessed by the physiotherapists who prepared the translation, as they evaluated whether the items covered a representative sample of the construct domain—the psychological readiness of injured athletes during the RTS phase of rehabilitation.

For the construct validity, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted using the principal axis factor (PAF) method [38]. The Bartlett test of sphericity and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy were used to assess the sufficiency of the sample population. The pattern matrix from the oblique rotation was used to examine the two-factor structure of the PRIA-RS [39].

The internal consistency was measured using Cronbach’s α coefficient. Values of Cronbach’s α greater than 0.7 indicate an adequate internal consistency, values above 0.8 suggest a good internal consistency, and values above 0.9 indicate an excellent internal consistency. The test–retest reliability was assessed by comparing the overall scores using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), along with the standard error of measurement (SEM) [40,41].

3. Results

The main demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Main demographic and clinical data of the study sample.

3.1. Face and Content Validity

The face validity assesses whether a measurement evaluates the intended factors. In this study, the translated scale appeared valid, and the instrument was well accepted by all participants. Specifically, the first sample group of 30 athletes agreed that the scale was a reasonable tool for evaluating psychological readiness and its components.

A measurement is considered to have a high content validity when it covers all aspects of the subject being assessed [42]. The content validity is the most desirable form of validity and should be supported by the concurrent validity [42]. In this study, the translation of the instrument was reviewed by physiotherapists and two psychometrics experts, who confirmed that the instrument included all the necessary questions.

3.2. Internal Consistency and Test–Retest Reliability

The internal consistency was measured using Cronbach’s α coefficient. Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.82, which is considered good [40,41]. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was 0.991 for the PRIA-RS, 0.994 for the factor “Insecurity, Self-confidence, Individual perception”, and 0.973 for the factor “Fear of Re-injury”. The standard error of the measurement (SEM) was measured in addition to the ICC, for a more thorough examination of the reliability. The SEM absolute scores were 3.15 for the PRIA-RS, 2.44 for the 1st factor, and 1.64 for the second. Then, it was presented in relation to the grand mean, where it was found that they were within acceptable limits (8.18–15.07% of the grand mean) (Table 2) [40].

Table 2.

Test–retest reliability (ICC and SEM) and internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) measures.

3.3. Construct Validity

The results of the EFA showed that the Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (641,275, df 45, p < 0.00) and the value of the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was high (0.703). Therefore, the data were appropriate to be used in a factor analysis [43,44]. The Principal Axis Factoring (PAF) method revealed a two-factor solution with eigenvalues from 4.42 to 1.94, accounting for 63.52% of the total variance. The communalities of the 10 items ranged from 0.32 to 0.88, with a mean number of 0.66. The factor loadings of the items from the pattern matrix ranged from 0.550 to 0.930 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Exploratory Factor Analysis: factor loadings, communalities, eigenvalues, and percentage of explained variance of the Psychological Readiness of Injured Athlete to Return to Sport (n = 113).

3.4. Concurrent Validity

In order to examine the concurrent validity of the PRIA-RS, the athletes completed the CR-IWQ, the SCQ-RARC, and the AQ-RARC questionnaire, all of which have a high content and concurrent validity and acceptable reliability indexes [30,31,32]. The concurrent validity assessment indicated that the PRIA-RS questionnaire and its factors showed a statistically significant correlation with the other three constructs. In particular, the PRIA-RS questionnaire showed a statistically significant and high correlation with the SCQ-RARC (r = 0.366, p < 0.05). The PRIA-RS factor “Insecurity, Self-confidence, Individual perception” correlated statistically significantly with the SCQ-RARC factors “Confidence due to Rehabilitation” (r = 0.307, p < 0.05) and “General Confidence” (r = 0.245, p < 0.05). The PRIA-RS factor “Fear of Re-injury” also showed a statistically significant correlation with the SCQ-RARC factors “Confidence due to Rehabilitation” (r = 0.276, p < 0.05) and “General Confidence” (r = 0.231, p < 0.05). Only the PRIA-RS factor “Fear of Re-injury” showed a statistically significant negative correlation with the CR-IWQ factor “Re-injury worry due to opponent’s ability” (r = −0.249, p < 0.05). The PRIA-RS questionnaire (r = 0.369, p < 0.05), factor “Insecurity, Self-confidence, Individual perception” (r = 0.346, p < 0.05), and factor “Fear of Re-injury” (r = 0.262, p < 0.05) indicated a statistically significant high correlation with the AQ-RARC factor “Functional attention” (Table 4).

Table 4.

Spearman r correlations among the factors of the PRIA-RS, SCQ-RARC, CR-IWQ, and AQ-RARC.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to cross-culturally validate the PRIA-RS questionnaire in Greek soccer athletes. A five-stage validation process was followed, in accordance with the principles of the ISPOR cross-cultural adaptation guidelines [37]. Participants found the scale easy to use. The results of this study were generally consistent with those of previous validations of the scale [9].

The impact of a sports injury on an athlete’s psychology varies depending on its severity and type [45]. Therefore, assessing an athlete’s psychological preparedness to return to training and competition is crucial for ensuring a safe return to sport (RTS) and reducing the risk of re-injury [9,24]. There is a need for specific instruments that assess an athlete’s psychological readiness during the RTS phase of recovery to ensure a safe return. However, there are limited options for scales available in Greek that assess the RTS for previously injured athletes [30,31,32].

The construct validity of the PRIA-RS questionnaire was assessed using an exploratory factor analysis (EFA). The primary goal of the EFA is to identify the number of factors among a set of variables and the degree to which these variables are related to the factors [46]. The factor analysis revealed two factors, which is consistent with the findings of Gomez-Piqueras et al. [9]. Specifically, the EFA identified the following two factors: (a) “Insecurity, Self-confidence, and Individual Perception” and (b) “Fear of Re-injury”, which together explained 63.52% of the total variance. These results, similar to those of Gomez-Piqueras et al., confirm that all the questions in the questionnaire are relevant and consistently adapted to the population of amateur soccer players in the injury recovery phase.

However, Gomez-Piqueras et al. [9] also performed a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in addition to an EFA, which showed a high degree of correlation between both factors and their corresponding items. In the present study, a CFA was not conducted, so further research using CFA is needed to (a) confirm the theoretical framework and (b) validate the initial number of factors identified through EFA. The similarity between the present study’s results and those of Gomez-Piqueras et al. lies in the uniformity of the samples. Both studies used soccer athletes with similar injury characteristics, which supports the consistency in the psychological adaptation of athletes in the same sport following an injury.

The interpretation of the first factor is complex, as it encompasses several aspects of psychological readiness. The initial questions (1, 2, and 4) assess the functional status of the injury site, the athlete’s emotional state, and the sense of security felt during recovery, respectively. The later questions (7, 9, and 10) explore the degree of pressure the athlete feels, their confidence when loading the injured limb, and their overall assessment of their condition before returning to sport, respectively. The second factor is more focused, with the first question (3) addressing the athlete’s physical condition, while the subsequent questions (6 and 8) relate to nervousness and the fear of re-injury.

In the sample of the present study, the athletes had an average score of 26.5 on the first factor (questions 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 9, and 10), where the maximum possible score was 35. In contrast, the mean score for the second factor (questions 3, 6, and 8) was 10.88, with a maximum score of 15. Gomez-Piqueras et al. [9] reported that the first factor comprises more general questions compared to the second factor. They also pointed out that the multiple stressors an injured athlete faces often exacerbate their anxiety, which then manifests as nervousness or a negative mood, leading to a lower score on the second factor.

In the present study, the lowest mean scores were recorded for questions 2 and 9, with values of 3.7 and 3.5, respectively. In contrast, the highest mean score for the first factor was recorded for question 1, with a value of 4.37. This highlights the relationship between the rehabilitation process and the athlete’s psychological readiness to return to sport.

Gomez-Piqueras et al. [9] reported that the relative risk of an athlete’s injury can be calculated using questions 4, 6, and 7 of the PRIA-RS, for up to 14 days after returning to the field. Specifically, athletes who scored below 3 on these questions in the Likert scale had a significantly higher risk of re-injury. The researchers also explained that an athlete who scores at or below 40 points on the questionnaire has a 46.90 times greater risk of re-injury than an athlete who scores above 40 points. Therefore, athletes scoring above 40 points are at considerably lower risk of re-injury, which is why the threshold was set at 40. While our study did not examine the effectiveness of the PRIA-RS in the Greek sports population, we plan to explore this in a future study.

To assess the concurrent validity of the PRIA-RS, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were used to evaluate its relationships with the SCQ-RARC, CR-IWQ, and AQ-RARC questionnaires [30,31,32]. These questionnaires are well-established and reliable tools for assessing various aspects of psychological readiness in Greek injured athletes [10]. A strength of the present study is the use of these three valid and reliable questionnaires to test the concurrent validity. Gomez-Piqueras et al. [9] emphasized the need to compare the results of the PRIA-RS with conceptually identical questionnaires, such as the I-PRRS (Injury Psychological Readiness to Return to Sport), RIAI (Re-Injury Anxiety Inventory), and ACL-RSI (Anterior Cruciate Ligament-Return to Sport after Injury), which have not yet been validated in Greek. In contrast, the present study compared the PRIA-RS with valid and reliable Greek questionnaires of similar content.

The PRIA-RS showed a strong and statistically significant correlation with the SCQ-RARC, as expected, because high scores on the SCQ-RARC factors indicate high levels of self-confidence, which are also reflected in high scores on the PRIA-RS. Furthermore, the factors of the PRIA-RS, “Insecurity, Self-confidence, Individual perception” and “Fear of re-injury”, correlated strongly with the factors “Self-confidence due to rehabilitation” (CO-R) and “General self-confidence” (G-CO) of the SCQ-RARC, as anticipated. High scores on both the PRIA-RS and SCQ-RARC indicate high levels of self-confidence.

PRIA-RS showed a high but non-statistically significant correlation with the AQ-RARC. According to the AQ-RARC, a high score on the first factor, “Functional Attention”, signals high levels of functional attention, which is positively correlated with the athlete’s self-confidence. This is consistent with the PRIA-RS, where high scores also reflect high levels of self-confidence, a finding confirmed in this study. A statistically significant high correlation was observed between the PRIA-RS factors and the AQ-RARC factor “Functional Attention”. However, the second factor of the AQ-RARC, “Distracted Attention”, did not correlate with any PRIA-RS factor. This is likely because the PRIA-RS does not include an item addressing potential distractions in the athlete’s attention. Given this, it is recommended to use both constructs when a clinician suspects that an athlete’s attention may be prone to distraction and wishes to correlate that distraction with the athlete’s psychological readiness.

No significant correlation was found between the overall scores of the PRIA-RS and the CR-IWQ. However, the PRIA-RS factor “Fear of re-injury” showed a strong negative correlation with the second factor of the CR-IWQ, “Concern of re-injury due to uncertainty”, as expected. A high score on the “Fear of re-injury” factor of the PRIA-RS indicates the absence of fear, which aligns with lower levels of anxiety and lower scores on the corresponding CR-IWQ factor. The lack of correlation between the total scores of the two questionnaires, and between the first factor of the PRIA-RS and the CR-IWQ, can be attributed to the fact that the CR-IWQ specifically assesses re-injury worry, a particular aspect of psychological readiness. In contrast, the PRIA-RS and its first factor, “Insecurity, Self-confidence, Individual perception”, provide a more holistic evaluation of psychological readiness, which differentiates it from the CR-IWQ.

Gomez-Piqueras et al. [9] assessed the concurrent validity of the PRIA-RS questionnaire by analyzing the correlations between each question and the final score of the questionnaire. The analysis revealed that six out of the ten questions showed moderate to high correlations with the total score. Specifically, questions 5 and 7 exhibited the highest correlations with the final score. All questions on the PRIA-RS questionnaire demonstrated correlations within the required range of 0.40 to 0.80 [47].

The internal consistency in the present study was consistent with the original English validation of the PRIA-RS questionnaire by Gomez-Piqueras [9]. The results from our study showed acceptable internal consistency and excellent intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) for the PRIA-RS factors. Gomez-Piqueras [9] calculated Cronbach’s α for the PRIA-RS with a sample of 102 soccer athletes, finding a high internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.81), but did not re-administer the questionnaire, and thus did not test the reliability of repeated measures. In contrast, our study assessed the test–retest reliability with an ICC analysis conducted two weeks apart, allowing sufficient time for reliable results [48]. In addition to the ICC values (0.973–0.994), the Standard Error of Measurement (SEM) was also calculated, with results (1.64–3.15) indicating a low measurement error [40].

The PRIA-RS questionnaire provides a comprehensive tool for assessing the psychological readiness of athletes to return to sport, evaluating key variables such as self-confidence, individual perception, insecurity, and fear of re-injury. By cross-culturally adapting the questionnaire to Greek, this study offers rehabilitation professionals a reliable tool to assess athletes’ psychological readiness as they return to competitive sports following an injury. The completion of the questionnaire can provide valuable insights into an athlete’s psychological state, highlighting potential areas of concern that may require further investigation by rehabilitation professionals. This can help predict the likelihood of re-injury and, in the long term, aid in its prevention.

However, the present study has several limitations that should be considered. First, the sample consisted only of male soccer players. Additionally, the athletes varied in playing experience and competitive level, leading to differences in their psychological readiness and eagerness to return to action. Moreover, the exclusive focus on male athletes limits the generalizability of the findings to female athletes, given that gender differences in psychological responses to musculoskeletal injuries have been documented in the literature [36]. Furthermore, the athletes’ desire to return to sport as soon as possible could have introduced an acquiescence effect [49], potentially skewing the results with higher scores. This effect should be taken into account and controlled for in future research [50].

Future studies should aim to conduct Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) to validate the theoretical framework of the PRIA-RS questionnaire. Further research should also involve athletes from other contact sports beyond football, as the original questionnaire was developed using only football players. Additionally, it is essential for future studies to assess psychological readiness in female athletes to explore any potential gender differences in readiness and return-to-sport outcomes. Furthermore, future research should examine the impact of the injury severity on the responses provided in the PRIA-RS questionnaire. Incorporating the injury severity could yield valuable insights into whether athletes sustaining more severe injuries demonstrate distinct levels of psychological readiness in comparison to their counterparts with less severe injuries. Finally, we should investigate how external and internal factors such as pressure from coaches/teams and athlete motivation influence PRIA-RS results.

5. Conclusions

The Greek version of the Psychological Readiness of Injured Athlete to Return to Sport (PRIA-RS) is a psychometric tool designed to assess the psychological readiness of injured athletes to return to sport (RTS). The PRIA-RS demonstrated a solid factorial structure, strong internal consistency, and excellent ICC reliability, making it suitable for both clinical and research applications. Future studies in Greece should aim to further validate the PRIA-RS across different populations, including female athletes and athletes from other contact sports.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C.; Methodology, D.K., A.K., E.P., M.T., E.K. and A.C.; Software, D.K.; Validation, D.K., A.K., E.P. and A.C.; Formal analysis, D.K., A.K., E.P., M.T., E.K. and A.C.; Investigation, D.K. and A.K.; Writing—original draft, D.K. and A.K.; Writing—review & editing, E.P., M.T., E.K. and A.C.; Supervision, A.C.; Project administration, A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the University’s Institutional Research Ethics Committee approved the study (5364/11 March 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend special thanks to Marina Kapreli, an English interpreter, for her valuable help, while translating and forming the final version of the PRIA-RS questionnaire in Greek.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Ερωτηματολόγιο Ψυχολογικής Ετοιμότητας του Τραυματισμένου Aθλητή κατά την Επιστροφή στο Άθλημα (OΔHΓΙΕΣ: Το ερωτηματολόγιο αυτό αξιολογεί την ψυχολογική σας ετοιμότητα ύστερα από έναν τραυματισμό, προκειμένου να επιστρέψετε στο αγωνιστικό πρόγραμμα με ασφάλεια. Aν ανησυχείτε για πιθανό επανατραυματισμό ή εάν αισθάνεστε ήρεμος κατά την επιστροφή σας στο αγωνιστικό πρόγραμμα, παρακαλώ τσεκάρετε το κουτάκι με την απάντηση που σας αντιπροσωπεύει. Δεν υπάρχουν σωστές ή λανθασμένες απαντήσεις. Μην αφιερώσετε πολύ χρόνο για να κάνετε την επιλογή σας. Aπαντήστε αυθόρμητα και ειλικρινά. Oι απαντήσεις είναι απολύτως εμπιστευτικές).

Table A1.

Ερωτηματολόγιο Ψυχολογικής Ετοιμότητας του Τραυματισμένου Aθλητή κατά την Επιστροφή στο Άθλημα (OΔHΓΙΕΣ: Το ερωτηματολόγιο αυτό αξιολογεί την ψυχολογική σας ετοιμότητα ύστερα από έναν τραυματισμό, προκειμένου να επιστρέψετε στο αγωνιστικό πρόγραμμα με ασφάλεια. Aν ανησυχείτε για πιθανό επανατραυματισμό ή εάν αισθάνεστε ήρεμος κατά την επιστροφή σας στο αγωνιστικό πρόγραμμα, παρακαλώ τσεκάρετε το κουτάκι με την απάντηση που σας αντιπροσωπεύει. Δεν υπάρχουν σωστές ή λανθασμένες απαντήσεις. Μην αφιερώσετε πολύ χρόνο για να κάνετε την επιλογή σας. Aπαντήστε αυθόρμητα και ειλικρινά. Oι απαντήσεις είναι απολύτως εμπιστευτικές).

| 1 |  | ΠOΛΥ ΚAΚH □ | ΚAΚH □ | OΥΤΕ ΚAΛH OΥΤΕ ΚAΚH □ | ΚAΛH □ | ΠOΛΥ ΚAΛH □ |

| 2 | Πώς είναι η διάθεσή σας; | ΠOΛΥ ΚAΚH □ | ΚAΚH □ | OΥΤΕ ΚAΚH □ OΥΤΕ ΚAΛH | ΚAΛH □ | ΠOΛΥ ΚAΛH □ |

| 3 | Πώς είναι η φυσική σας κατάσταση ενόψει μίας πιθανής επιστροφής στην ομάδα; | ΠOΛΥ ΚAΚH □ | ΚAΚH □ | OΥΤΕ ΚAΚH □ OΥΤΕ ΚAΛH | ΚAΛH □ | ΠOΛΥ ΚAΛH □ |

| 4 | Πώς αξιολογείτε τη λειτουργικότητα της τραυματισμένης σας περιοχής; | ΠOΛΥ ΚAΚH □ | ΚAΚH □ | OΥΤΕ ΚAΚH □ OΥΤΕ ΚAΛH | ΚAΛH □ | ΠOΛΥ ΚAΛH □ |

| 5 | Aισθάνεστε κάποια ενόχληση ή κάποιο κώλυμα που σας αποτρέπει να προπονηθείτε σε κανονικό ρυθμό; | ΝAΙ □ | - | ΔΕΝ ΞΕΡΩ □ | - | OΧΙ □ |

| 6 | Aισθάνεστε νευρικά σχετικά με την επιστροφή στην κανονική προπόνηση με την ομάδα; | ΝAΙ □ | - | ΔΕΝ ΞΕΡΩ □ | - | OΧΙ □ |

| 7 | Πόσο ασφαλής αισθάνεστε όταν συμμετέχετε σε φυσικές δραστηριότητες ή όταν κινείτε την τραυματισμένη περιοχή; | ΕΛAΧΙΣΤA □ | ΛΙΓO □ | OΥΤΕ ΠOΛΥ OΥΤΕ ΛΙΓO □ | ΠOΛΥ □ | ΠAΡA ΠOΛΥ □ |

| 8 | Δώστε μία εκτιμώμενη πιθανότητα να βιώσετε σύντομα έναν ίδιο επανατραυματισμό. | 80–100% □ | 60–80% □ | 40–60% □ | 20–40% □ | 0–20% □ |

| 9 | Πόση πίεση αισθάνεστε από τον περίγυρό σας όσον αφορά την επιστροφή σας στην προπόνηση με την ομάδα; | ΥΠΕΡΒOΛΙΚH □ | ΥΨHΛH □ | ΚAΝOΝΙΚH □ | ΧAΜHΛH □ | ΜHΔΕΝΙΚH □ |

| 10 | Πώς θα αξιολογούσατε τη γενική σας κατάσταση ενόψει μίας πιθανής επιστροφής σας σε πλήρη προπόνηση; | ΠOΛΥ ΚAΚH □ | ΚAΚH □ | OΥΤΕ ΚAΛH OΥΤΕ ΚAΚH □ | ΚAΛH □ | ΠOΛΥ ΚAΛH □ |

Βεβαιωθείτε ότι απαντήσατε σε όλες τις ερωτήσεις. Ευχαριστώ για τη συνεργασία.

References

- SFIA. 2022 Sports, Fitness, and Leisure Activities Topline Participation Report; Sports & Fitness Industry Association: Laurel, MD, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Åman, M.; Forssblad, M.; Henriksson-Larsén, K. Incidence and severity of reported acute sports injuries in 35 sports using insurance registry data. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2016, 26, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hulteen, R.M.; Smith, J.J.; Morgan, P.J.; Barnett, L.M.; Hallal, P.C.; Colyvas, K.; Lubans, D.R. Global participation in sport and leisure-time physical activities: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev. Med. 2017, 95, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bueno, A.M.; Pilgaard, M.; Hulme, A.; Forsberg, P.; Ramskov, D.; Damsted, C.; Nielsen, R.O. Injury prevalence across sports: A descriptive analysis on a representative sample of the Danish population. Inj. Epidemiol. 2018, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Valenciano, A.; Ruiz-Pérez, I.; Garcia-Gómez, A.; Vera-Garcia, F.J.; De Ste Croix, M.; Myer, G.D.; Ayala, F. Epidemiology of injuries in professional football: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2019, 54, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smpokos, E.; Mourikis, C.; Theos, C.; Linardakis, M. Injury prevalence and risk factors in a Greek team’s professional football (soccer) players: A three consecutive seasons survey. Res Sports Med. 2019, 27, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hägglund, M.; Waldén, M.; Ekstrand, J. Injury incidence and distribution in elite football—A prospective study of the Danish and the Swedish top divisions. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2005, 15, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbe, J.H.; van Beijsterveldt, A.M.M.; van der Knaap, S.; Stege, J.; Verhagen, E.A.; Van Mechelen, W.; Backx, F.J. Injuries in professional male soccer players in the Netherlands: A prospective cohort study. J. Athl. Train. 2015, 50, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Piqueras, P.; Ardern, C.; Prieto-Ayuso, A.; Robles-Palazón, F.J.; Cejudo, A.; Baranda, P.S.; Olmedilla, A. Psychometric Analysis and Effectiveness of the Psychological Readiness of Injured Athlete to Return to Sport (PRIA-RS) Questionnaire on Injured Soccer Players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkikopoulos, G.; Chronopoulou, C.; Christakou, A. Examining re-injury worry, confidence and attention after a sport musculoskeletal injury. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2020, 60, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiese-Bjornstal, D.M.; Smith, A.M.; Shaffer, S.M.; Morrey, M.A. An integrated model of response to sport injury: Psychological and sociological dynamics. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 1998, 10, 46–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardern, C.L.; Taylor, N.F.; Feller, J.A.; Webster, K.E. A systematic review of the psychological factors associated with returning to sport following injury. Br. J. Sports Med. 2013, 47, 1120–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forsdyke, D.; Smith, A.; Jones, M.; Gledhill, A. Psychosocial factors associated with outcomes of sports injury rehabilitation in competitive athletes: A mixed studies systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonesson, S.; Kvist, J.; Ardern, C.; Österberg, A.; Silbernagel, K.G. Psychological factors are important to return to pre-injury sport activity after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: Expect and motivate to satisfy. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2017, 25, 1375–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischerauer, S.F.; Talaei-Khoei, M.; Bexkens, R.; Ring, D.C.; Oh, L.S.; Vranceanu, A.M. What is the relationship of fear avoidance to physical function and pain intensity in injured athletes? Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2018, 476, 754–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clement, D.; Arvinen-Barrow, M.; Fetty, T. Psychosocial responses during different phases of sport-injury rehabilitation: A qualitative study. J. Athl. Train. 2015, 50, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podlog, L.; Wadey, R.; Stark, A.; Lochbaum, M.; Hannon, J.; Newton, M. An adolescent perspective on injury recovery and the return to sport. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2013, 14, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardern, C.L.; Taylor, N.F.; Feller, J.A.; Webster, K.E. Fifty-five per cent return to competitive sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis including aspects of physical functioning and contextual factors. Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 1543–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podlog, L.; Banham, S.M.; Wadey, R.; Hannon, J.S. Psychological readiness to return to competitive sport following injury: A qualitative study. Sport Psychol. 2015, 29, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwachukwu, B.U.; Adjei, J.; Rauck, R.C.; Chahla, J.; Okoroha, K.R.; Verma, N.N.; Allen, A.A.; Williams, R.J. How much do psychological factors affect lack of return to play after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction? A systematic review. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2019, 7, 2325967119845313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piussi, R.; Berghdal, T.; Sundemo, D.; Grassi, A.; Zaffagnini, S.; Sansone, M.; Samuelsson, K.; Senorski, E.H. Self-Reported symptoms of depression and anxiety after ACL injury: A Systematic Review. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2022, 10, 23259671211066493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, A.L.; Feller, J.A.; Hewett, T.E.; Webster, K.E. Smaller change in psychological readiness to return to sport is associated with second anterior cruciate ligament injury among younger patients. Am. J. Sports Med. 2019, 47, 1209–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christakou, A.; Stavrou, N.A.; Psychountaki, M.; Zervas, Y. Re-injury worry, confidence and attention as predictors of a sport re-injury during a competitive season. Res. Sports Med. 2020, 30, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardern, C.L.; Glasgow, P.; Schneiders, A.; Witvrouw, E.; Clarsen, B.; Cools, A.; Bizzini, M. Consensus statement on return to sport from the First World Congress in Sports Physical. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 853–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dijkstra, H.P.; Pollock, N.; Chakraverty, R.; Ardern, C.L. Return to play in elite sport: A shared decision-making process. Br. J. Sports Med. 2017, 51, 853–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Piqueras, P.; Sainz de Baranda, P.; Ortega, E.; Contreras, O.; Olmedilla, A. Design and validation of a questionnaire on the perception of the athlete regarding his return to training after injury. Rev. Psicol. Deporte 2014, 23, 479–487. [Google Scholar]

- Glazer, D. Development and preliminary validation of the injury-psychological readiness to return to sport (I-PRRS) scale. J. Athl. Train. 2009, 44, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, N.; Thatcher, J.; Lavallee, D. A preliminary development of the Re-Injury Anxiety Inventory (RIAI). Phys. Ther. Sport 2010, 11, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, K.E.; Feller, J.A.; Lambros, C. Development and preliminary validation of a scale to measure the psychological impact of returning to sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery. Phys. Ther. Sport 2008, 9, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christakou, A.; Zervas, Y.; Stavrou, N.A.; Psychountaki, M. Development and validation of the Causes of Re-Injury Worry Questionnaire. Psychol. Health Med. 2011, 16, 94–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christakou, A.; Stavrou, N.A.; Psychountaki, M.; Zervas, Y. Development and validation of sport confidence questionnaire of rehabilitated athletes returning to competition. Ann. Orthop. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2019, 2, 1021. [Google Scholar]

- Christakou, A.; Zervas, Y.; Psychountaki, M.; Stavrou, N.A. Development and validation of the Attention Questionnaire of Rehabilitated Athletes Returning to Competition. Psychol. Health Med. 2012, 17, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatcher, L.; Stepanski, E.J. A Step-by-Step Approach to Using the SAS System for Univariate and Multivariate Statistics; SAS Institute: Cary, NC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Calvert, M.; Brundage, M.; Jacobsen, P.B.; Schünemann, H.J.; Efficace, F. The CONSORT Patient-Reported Outcome (PRO) extension: Implications for clinical trials and practice. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2013, 11, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parlakidis, K.; Krokos, D.; Sagredaki, M.-L.; Kontopoulos, L.A.; Christakou, A. Examining the Relationship between Psychological and Functional Status after a Sports Musculoskeletal Injury. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christakou, A.; Gkiokas, G.; Valsamis, N.; Paraskevopoulos, E.; Papandreou, M. Examining the Relationship and the Gender Differences between Re-Injury Worry, Confidence, and Attention after a Sport Musculoskeletal Injury. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, D.; Grove, A.; Martin, M.; Eremenco, S.; McElroy, S.; Verjee-Lorenz, A.; Erikson, P. Principles of good practice for the translation andcultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcomes (PRO)measures: Report of the ISPOR task force for translation and cultural adaptation. Value Health 2005, 8, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terwee, C.B.; Bot, S.D.; de Boer, M.R.; van der Windt, D.A.; Knol, D.L.; Dekker, J.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C.W. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2007, 60, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, J.; Costello, A.; Kellow, J. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis. In Best Practices in Quantitative Methods; Osborne, J., Ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 86–99. [Google Scholar]

- Weir, J.P. Quantifying test-retest reliability using the intraclass correlation coefficient and the SEM. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2005, 19, 231–240. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, I.S. Using Multivariate Statistics; Harper Collins Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Worthington, R.W.; Whittaker, T.A. Scale development research: A content analysis and recommendations for best practices. Couns. Psychol. 2006, 34, 806–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babbie, E. (Ed.) Conceptualization and measurements. In Practice of Social Research; Wadsworth Publishing Company: Belmont, CA, USA, 1992; pp. 113–135. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, P. (Ed.) Validity of psychosocial tests. In The Handbook of Psychological Testing; Routledge: London, UK, 1995; pp. 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, L.H.; Carroll, D. The context of emotional responses to athletic injury: A qualitative analysis. J. Sport Rehabil. 1998, 7, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, J.H. Factor analysis in counselling psychology research, training, and practice: Principles, advances, and applications. Couns. Psychol. 2006, 34, 684–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streiner, D.L.; Norman, G.R.; Cairney, J. Health Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide to Their Development and Use; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, R.G.; Menezes, A.; Horovitz, L.; Jones, E.C.; Warren, R.F. A comparison of two time intervals for test-retest reliability of health status instruments. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2003, 56, 730–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danner, D.; Aichholzer, J.; Rammstedt, B. Acquiescence in personality questionnaires: Relevance, domain specificity, and stability. J. Res. Pers. 2015, 57, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrando, P.J.; Morales-Vives, F.; Lorenzo-Seva, U. Assessing and controlling acquiescent responding when acquiescence and content are related: A comprehensive factor-analytic approach. Struct. Equ. Model. 2016, 23, 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).