1. Introduction

The annual average daily traffic volume (AADT) is a crucial metric in road traffic management extensively used for traffic planning, road infrastructure development, and forecasting traffic demand. It also provides a comparative basis for assessing factors that adversely affect economic growth or quality of life across different cities. The metric is typically used to evaluate the road traffic congestion coefficient, which can highlight instances where the traffic exceeds road capacities, leading to congestion.

Predicting long-term traffic volume requires substantial computational resources and depends heavily on hardware capabilities; thus, short-term forecasting of traffic conditions often takes precedence. Extensive research has been conducted on these short-duration predictions, focusing on approximately one-hour intervals. Despite the development and adoption of various short-term prediction models, their reliability can be compromised by incomplete datasets. Hence, the acquisition of precise and comprehensive raw data is crucial.

Road traffic volume is defined as the total number of vehicles traversing a particular point or segment of a road within a specific time unit. Traffic data collection, which includes differentiating the traffic volume by vehicle type and direction on an hourly basis, is known as a traffic volume survey. Current practices in traffic volume surveys are categorized into occasional and continuous types. Occasional surveys, which provide essential data for analyzing the overall road usage, are performed annually and target specific points and sections. These are further subdivided by the targeted roads—general national roads and, for the October survey, expressways and local roads. Techniques for occasional surveys range from mechanical methods using portable traffic equipment to video surveys with closed-circuit television (CCTV) and manual counts by personnel.

Continuous surveys deploy automatic vehicle classification (AVC) systems equipped with sensors that continuously record traffic data around the clock at designated points. These systems gather detailed information on the vehicle type, direction, and timing. Technologies used in continuous surveys include loop and piezoelectric sensors embedded in the roadway, artificial-intelligence-driven video analysis from CCTV footage, and vehicle license plate recognition systems that integrate CCTV with a vehicle specifications database.

Among the continuous traffic volume survey methods, those utilizing buried sensors encounter several challenges. Frequent sensor damage caused by road wear from heavy vehicles often results in gaps in the traffic volume data. Similarly, video survey methods face data losses arising from equipment malfunctions and adverse weather conditions. Furthermore, the traffic volume survey equipment designated for 365-day measurement suffers from inconsistent maintenance times due to communication disruptions, controller malfunctions, and sensor damage. These factors result in prolonged periods where there are missing or abnormal data, rendering it challenging to provide accurate observed traffic volume data. Consequently, the traffic volume information collected from such continuous survey equipment may not accurately reflect the actual traffic volumes owing to a combination of technical limitations, controller defects, sensor errors, external environmental factors, and communication issues.

This study aims to develop and verify a deep-learning-based traffic volume correction and prediction algorithm to enhance the reliability of high-quality traffic volume information and raw data for use in national infrastructure planning, as defined in Article 102 of the Road Act and under Article 88 of the National Transport System Efficiency Act. The spatial scope of this study encompasses 551 points where general national road traffic volume survey equipment (AVC) is installed to calculate the AADT. The temporal scope includes hourly and daily continuous traffic volume data from the past decade (2010 to 2020) collected in real-time from the AVC equipment installed on general national roads.

The main objective is to correct and predict traffic volume by applying a cyclic model-based algorithm to short-cycle complex seasonal time series information while specifically addressing the issue of frequent missing data during the traffic volume data collection process. Most importantly, this study aims to minimize the out-of-sample issues that commonly occur during model construction by comparing and verifying the actual observed traffic volume data against those obtained using the proposed methodology, thereby ensuring reliable traffic volume information.

Additionally, this study focuses accurately predicting traffic volume, which has various potential applications in the field of road traffic. Specifically, it aims to provide more reliable traffic volume information by addressing the issue of missing data owing to the failure of traffic information collection equipment, thereby contributing to improved travel reliability and enhanced transportation planning and management.

In this study, a power-function-based long short-term memory (LSTM) model algorithm is proposed to enhance the model’s ability to recognize uncertainty and long-term trend patterns that accurately reflect the characteristics of traffic volume.

2. Review of Related Studies

The introduction of advanced traffic volume survey equipment capable of automatically detecting traffic volumes has allowed for addressing the limitations of traditional traffic surveys by reducing outliers and missing values. However, the unpredictability of the traffic volume data due to equipment malfunctions and communication disruptions continues to pose significant challenges. Consequently, extensive research has been conducted to correct and predict the traffic volume data. These studies fall into three primary categories: (1) traffic volume correction studies utilizing historical data, (2) traffic volume prediction studies employing statistical learning algorithms, and (3) traffic-volume-related prediction studies using deep learning techniques.

2.1. Traffic Volume Correction and Methods Based on Historical Data

In Texas and Georgia, USA, the missing rates of traffic volume collection equipment have been reported at approximately 15–90% and 5–14%, respectively. In Alberta, Canada, an analysis over seven years revealed average missing rates ranging from 10% to 40% [

1,

2]. Although several studies have attempted to address these discrepancies, the methods predominantly rely on historical data from the same locations. These statistical techniques and algorithms, although useful, cannot fully eliminate the uncertainty associated with traffic volume. Relying on historical data for traffic volume correction is time-consuming and often ineffective when traffic patterns undergo significant changes. Moreover, if the reliability of the historical traffic volume data is questionable, corrections based on subjective analyst judgment or experience can lead to distorted interpretations of the time series data.

Mei et al. [

3] enhanced short-term traffic volume prediction by integrating historical data with transition matrices and proposing an absorbing Markov chain (AMC) model. In terms of prediction accuracy, their findings suggest that the AMC model outperforms both the seasonal autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) and neural network models.

Myung-Sik et al. [

4] developed an algorithm designed to eliminate outliers and correct missing values in the toll collection system data. They determined the algorithm’s applicability to various traffic flow scenarios across different sections of highways during weekdays, holidays, and special event periods.

Ji-Yeon et al. [

5] implemented traffic volume corrections using profile-based mean correction, regression correction with time-specific data from similar detectors, and autoregression with complete daily traffic data from similar detectors through significance tests of monthly and daily traffic volume change patterns, comparisons of similar traffic volume change patterns, and cluster analysis of daily average traffic volume change patterns.

Jeong-Yeon et al. [

6] reported that historical-data-based correction methods were more accurate than the adjacent point reference method. Among three techniques using historical data, applying the same period’s historical data, regression analysis, and lane usage rates, the replacement of historical data from the same period and regression analysis of front and rear points presented the most reliable estimates.

Seung-Weon and Ju-Sam [

7] suggested correcting the missing traffic volumes by calculating the axle correction coefficients derived from the cumulative number of axles detected by piezo sensors. This method exhibited a lower error rate than the spatial trend correction method for specific points.

Ha et al. [

8] developed an autoregressive analysis method using traffic volume data from the same time as the target for correction and a seasonal time series analysis correction method using data from the same point as the target. Their findings indicated that the autoregressive method, which considers the current time points, presented fewer errors when compared to the time series method, indicating that present conditions influence the traffic volumes more significantly than historical data.

2.2. Traffic Volume Prediction Based on Statistical Learning

Traffic volume prediction typically utilizes a data-driven approach based on statistical techniques, which can be classified into parametric and nonparametric estimation methods [

9]. The parametric techniques include traditional linear and nonlinear regression methods [

10,

11,

12,

13], historical average algorithms, moving averages, smoothing techniques [

14], and autoregressive linear processes [

12,

13,

15]. The selection of the algorithm depends on the periodicity and variability of the traffic volume data, with the autoregressive moving average (ARMA) and ARIMA being the most commonly employed linear parametric models.

In particular, the ARIMA model is notable for its application to differenced time series, addressing the non-stationarity and lack of mean reversion in the original series through differencing. This model involves detrending and deseasonalizing the data, applying the ARMA model, and subsequently reintegrating the trends and seasonality during the estimation phase. The ARIMA model is known for its effectiveness and is often improved by incorporating seasonal adjustments, as traffic volume data typically exhibit pronounced seasonal trends. This enhancement is captured in the seasonal ARIMA (SARIMA) model, which has been shown to provide more accurate predictions for traffic data with strong seasonal patterns [

16].

Nonlinear parametric models, such as the generalized linear mixed models, fuzzy logic, and genetic algorithms, require analysts to make subjective judgments regarding the form of nonlinearity, and their complex estimation processes can deter widespread usage. Spatial statistical methods, such as the Kriging interpolation, are used to predict traffic volumes by utilizing data from spatially related areas. However, these methods are typically suitable only for road segments with strong spatial interrelationships and are considered to be limited in their explanatory power for univariate analysis.

Table 1 lists the studies conducted on traffic volume prediction based on statistical learning algorithms.

2.3. Deep-Learning-Based Traffic Volume Prediction

Existing studies on traffic volume correction and prediction have primarily relied on historical data for corrections and statistical learning algorithms for both correction and prediction. However, with recent advancements in data collection, management, and analysis technologies, there has been an increasing focus on employing various methods to correct missing data and predict future traffic volumes.

Various machine-learning-based anomaly detection techniques have been developed, including classification-based, nearest-neighbor-based, clustering-based, and statistical anomaly detection methods. Additionally, deep-learning-based techniques, which integrate dimensionality reduction with anomaly detection, have been introduced [

10].

Yisheng et al. [

18] employed a deep learning approach using the stacked auto-encoder model, applying a greedy layer-wise unsupervised learning algorithm for initial deep network pre-training followed by a fine-tuning process to enhance prediction performance.

Fusco et al. [

19] analyzed the effectiveness of explicit models, such as dynamic traffic assignment, and implicit (data-driven) models, including artificial neural networks and Bayesian networks, for short-term prediction in urban traffic networks, which are crucial for intelligent transportation system applications. Explicit models make predictions at 15 min intervals, whereas implicit models present predictions at 5 min intervals.

Cho et al. [

20] developed deep learning models to predict public bicycle rental volumes, evaluating exponential smoothing, ARIMA, and LSTM models and finding that deep learning models showed superior performance.

2.4. Distinctions from Prior Research

Prior research on traffic volume prediction has predominantly utilized historical data and conventional statistical methods. These approaches typically require substantial time for generating predictions and may fail to forecast volumes for specific traffic segments. With recent advances in computational technology, deep learning techniques have been introduced for predicting traffic volumes. However, to date, no studies have employed LSTM models for this purpose. This study distinguishes itself by enhancing the time series deep learning framework, specifically through modifications to the LSTM forget gate, thereby improving the accuracy of traffic volume predictions.

3. Analysis and Procedure of the Development Model

3.1. Analysis of the Development Model

This study evaluates the traditional statistical models (ARIMA, SARIMA) alongside deep learning models (recurrent neural network (RNN), LSTM, power-function-based LSTM) to select suitable models and propose effective algorithms by addressing their limitations.

- (1)

ARIMA

The ARIMA model is a well-established time series analysis method that incorporates trends and seasonality by performing seasonal and first differencing, rendering the series stationary, as expressed in Equation (1):

Here, represents the trend, represents the seasonality, and represents the randomness.

The ARIMA model extends a typical ARMA model where, if the first difference is zero, it represents a stationary series. The formula for estimating the ARIMA model, which combines first-differenced ARMA, is expressed in Equation (2),

where

denotes the error term. However, the ARIMA model is best suited to contexts with short seasonal cycles owing to its structure, which limits its effectiveness in analyzing long seasonal cycles and handling multiple seasonalities.

- (2)

SARIMA

The SARIMA model integrates the seasonal autoregressive model and seasonal moving average model within the ARIMA framework. The model, as formulated in Equation (3), accommodates the probabilistic characteristics of seasonality (m),

where p denotes the non-seasonal autoregressive order, d denotes the degree of differencing, q denotes the non-seasonal moving average order, P denotes the seasonal autoregressive order, D denotes the degree of seasonal differencing, Q denotes the seasonal moving average order, and m represents the number of observations per year (indicating annual seasonality).

The distinction between ARIMA and SARIMA lies in SARIMA’s capacity to encapsulate the seasonal cycle (m), as expressed in Equation (4),

where

denotes the error term (also known as white noise) and

represents the backward shift operator. If the traffic volume data cycle is recorded monthly, this equation can be modified to Equation (5):

- (3)

RNN

RNN is predominantly utilized for time series analysis and is particularly adept at processing sequential data. A defining feature of the RNN is its state vector (also known as the hidden unit), which forms a singular neural structure for the sequence and retains the memory of all preceding elements. The schematic recursive structure of an RNN incorporating the backpropagation through a time algorithm is presented in

Figure 1 [

21].

A major assumption for different traditional statistical learning models is the independence among data samples. However, this assumption does not hold for sequential data, where dependencies exist among individual elements over time. This characteristic is particularly relevant to the traffic volume data analyzed in this study, negating the typical neural network advantage of processing each data sample independently.

Within an RNN, the transfer of information through the network’s weight matrices is described by the following equations:

In RNNs, the weights are designed to handle variable-length sequences. Each timestep receives a new input value, thus updating the hidden state, . The information is sequentially relayed throughout the network over time, with each prior input stored as memory, thus enhancing the processing of incoming data.

- (4)

LSTM

LSTM networks, a type of traditional RNN, are designed to address the gradient vanishing problem that occurs during the training processes, particularly when there is a significant time gap between the relevant information and its point of use in long-term trend data. This issue causes the gradient to diminish progressively during backpropagation, substantially reducing the network’s learning capability. In contrast to that of the standard RNNs, the LSTM architecture incorporates a cell state along with the hidden state, which helps in preserving information over longer sequences.

In this study, the LSTM model was employed to compare its predictive power against that of the newly developed power-function-based LSTM model. The standard LSTM model is structured as a relatively simple multi-layered neural network optimized for predicting short-term time steps (e.g., one hour ahead) using a single window. The predictive accuracy of the LSTM model varies with the time steps. Structurally, a linear transformation layer is inserted between the data input and prediction layers owing to limitations of the algorithm. While enabling fast computation, this layer reduces the model’s predictive performance. The model relies primarily on the values and features of the immediately preceding time step (t = 0) to predict the next time step, often failing to capture long-term trends and characteristics effectively.

- (5)

Proposed Power-Function-Based LSTM Model

This study introduces a power-function-based LSTM model to address the challenges presented by the forget gate in the conventional LSTM models. The employed LSTM model is an RNN that includes an LSTM hidden layer. When dealing with lengthy input streams without explicitly identified start and end points, the state of the LSTM can expand indefinitely, thus potentially destabilizing the network. To overcome this issue, we implemented a method of resetting the memory cell contents before initiating a new sequence. The use of an LSTM with a forget gate aims to prevent instability or interruptions during the learning process.

3.2. Development Model Analysis Procedure

Figure 2 depicts the procedure for developing the deep-learning-based model. Initially, the process involved establishing baseline values for traffic volume data, detecting anomalies in the raw data, and conducting data validation and preprocessing to correct and predict the traffic volume. Subsequently, datasets were organized for anomaly detection in traffic volume data, including a training set exclusively comprising normal values, a validation set with normal values, a secondary validation set containing both normal values and anomalies, and a test set comprising both normal values and anomalies. The third step involved defining the characteristics of the data to ensure appropriate data transfer suitable for each deep learning structure before the actual implementation of the deep learning model. The fourth step addressed the challenge of gradient vanishing during data analysis by setting input sequences for traffic volume prediction to construct the deep learning model. An architecture was then developed to evaluate and validate the predictive power of the devised model.

4. Statistical Learning Verification and Machine Learning Model Analysis and Evaluation

4.1. Statistical Learning Verification Design

Previous studies have commonly employed a preprocessing process to correct data anomalies before training the deep learning models. This approach, although necessary in the absence of actual values, tends to complicate the analysis process and significantly reduces the processing speed. Moreover, the use of simple interpolation methods during the correction phase can degrade the data quality. In this study, where actual values are available, the predictive power was verified without prior data correction, thereby simplifying the analysis process and enhancing efficiency. This study evaluated the model’s performance using certain metrics, such as the mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), the MAE, the root mean squared error (RMSE), and the coefficient of determination (R

2), and formulated additional data-missing scenarios for analysis.

Figure 3 depicts the design procedure for the time series prediction performance verification.

Bayesian optimization was conducted using the GPyOpt 1.2.6 library, thus necessitating the determination of candidate values for each hyperparameter. Values for certain parameters, such as the learning rate and the dropout rate, were established based on the existing literature. Additionally, this study explored three distinct and arbitrarily selected network architecture variations.

For the coding and implementation of experiments, the Python 3.12.4 programming language and Keras 2.3 were employed. Keras is an open-source project that offers a high-level API that supports the implementation of deep neural networks along with libraries, such as TensorFlow 2.10 and Theano 1.0.0. In this study, Keras was utilized in addition to TensorFlow, thus providing advantages in rapid prototyping and experimental flexibility through its simple API. This API supports modular neural network construction via the integration of various layers, activation functions, loss functions, and optimizers, and it includes provisions for most conventional deep learning components. Despite its broad utility, Keras may present limitations for constructing custom or novel solutions, for which TensorFlow may be a more appropriate choice. Notably, Keras incorporates an LSTM implementation featuring a forget gate, as described by Gers et al. (2000) [

22].

4.2. Machine Learning Model Analysis and Evaluation

- (1)

SARIMA Model Analysis Results

In evaluating the SARIMA model, the analysis of sample errors revealed no discernible patterns in the residuals between the estimated and actual values, suggesting the absence of significant heterogeneity issues; therefore, no additional log transformations were necessary. The Ljung–Box (LB) test was conducted to verify the accuracy of the model judgments. The LB test yielded a significance probability of 0.04, which is below the threshold of 0.1, indicating minimal autocorrelation. Consequently, the optimal parameters for the SARIMA model were determined through the auto grid searching method without the need for further log transformations or differencing.

The selection of optimal parameters was guided by Akaike’s information criterion (AIC), the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), and various significance tests. The results are summarized in

Table 2.

The overall prediction results indicated excellent performance, averaging approximately 85%; however, there was a notable decline in the prediction accuracy due to long-term missing data from 2019, which adversely affected the model’s ability to reflect the periodicity and trends accurately.

Table 3 presents the evaluation results of the SARIMA (4,1,3)(4,0,3) 12 model, revealing the discrepancy between the actual and predicted values, which ranged from a minimum of 3.28% to a maximum of 14.59%. Although the SARIMA model typically uses MAPE to estimate prediction errors, for consistency in comparisons across the statistical, machine learning, and deep learning models, MAPE was converted to MAE. The converted MAE was analyzed to be 0.158.

- (2)

Prophet Model Analysis

A separate analysis was conducted using the min–max scaling method to standardize the range of data values. Evaluation metrics included RMSE, MAE, and R

2. The analysis focused on two specific points, as detailed in

Table 4. Given its nature as a univariate regression model, R

2, which indicates the linear fit, serves as a measure of prediction accuracy.

Figure 4 depicts the results of predicting the hourly traffic volume at point 10001 using the Prophet model, where MAE is 0.117, RMSE is 0.147, and R

2 is 0.914, indicating considerably high predictive performance.

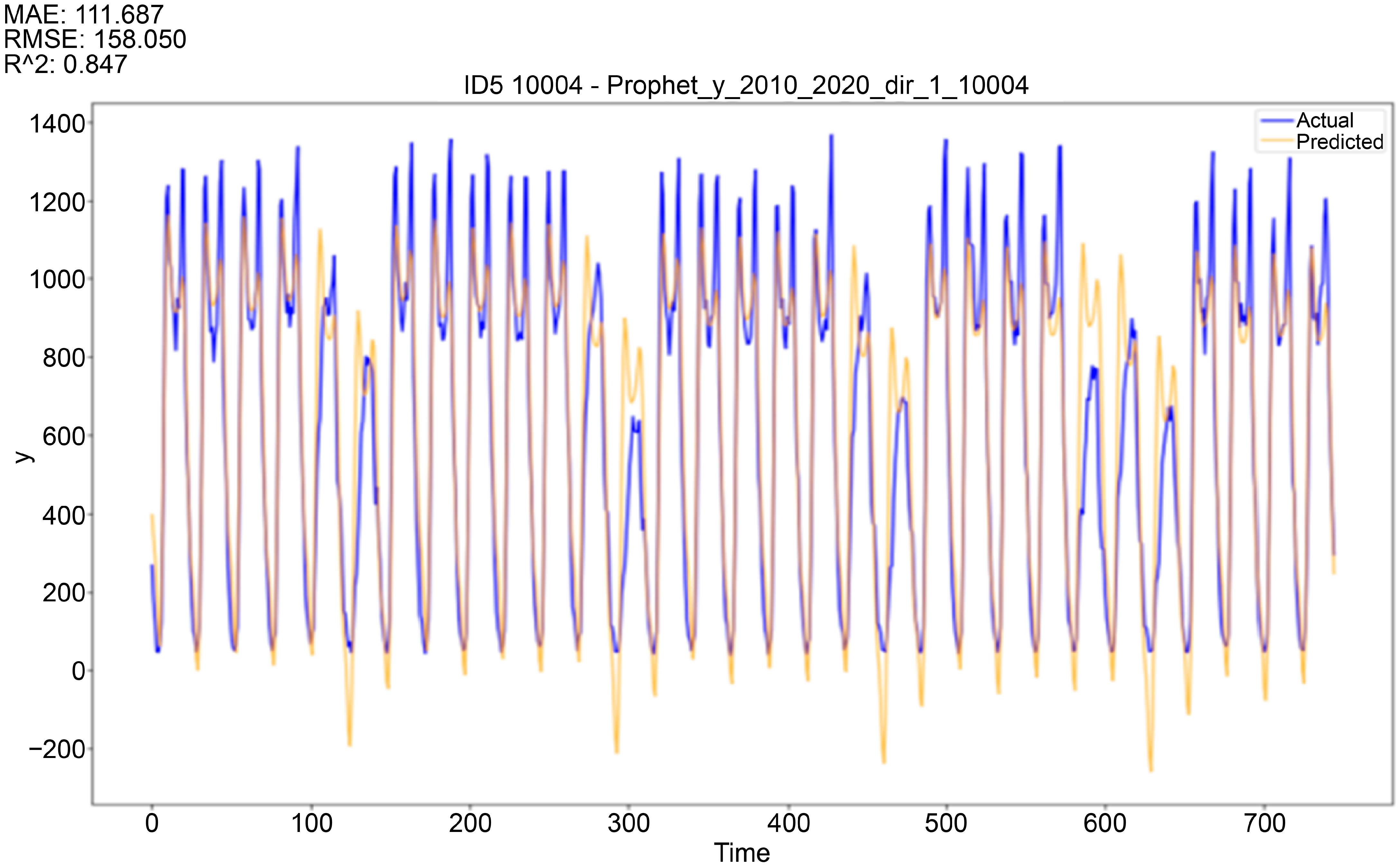

Figure 5 presents the results of predicting the hourly traffic volume at point 10004 using the Prophet model. The blue line represents the actual traffic values, and the yellow line represents the predicted values. For point 10001, the regularity in the past time series patterns (seasonality, periodicity) was confirmed, leading to a high predictive performance, with an MAE of 0.117 and an RMSE of 0.147.

However, for point 10004, irregular past time series patterns presented lower predictive performance, with an MAE of 111.687, an RMSE of 158.050, and an R2 of 0.847, when compared to point 10001. This indicates the presence of uncertainties that are not recognized by the data. To address these limitations, analyses utilizing deep-learning-based models were conducted.

- (3)

LSTM Model

The LSTM model was utilized to evaluate the predictive power of the proposed LSTM model, which incorporates a power function. The predictive accuracy of the LSTM model varies based on the time point, as shown in

Figure 6. Owing to the structural limitations of the algorithm, a linear transformation layer is incorporated between the input values (inputs) and the predicted outputs (predictions). This architecture lacks densely nonlinear hidden layers between the input and output layers, which, while enhancing the computational speed, considerably diminishes the predictive performance.

Furthermore, the model predicts the subsequent time step based solely on the values and characteristics of the immediately preceding time step (t = 0). This approach does not adequately capture the long-term trends and characteristics inherent in the data.

- (4)

Proposed LSTM Model Based on Power Function

Previous efforts to modify the LSTM architectures have aimed at enhancing the inference capabilities for data characterized by long-term trends, typically yielding similar performance levels. However, our analysis identified inconsistencies in the LSTM performance. In particular, within the forget gate, the memory cell,

, which stores past data, is described by Equation (8):

Despite the superior performance of the LSTM models with forget gates over the standard LSTM or RNN models, they frequently suffer significant information loss during the decay process, where non-essential information is discarded using a Sigmoid function. Shivangi et al. [

23] suggested an improved decay function using exponential functions to address this issue. However, exponential functions still led to excessive information loss in datasets with pronounced long-term trends. This effect was notably severe in data with substantial long-term dependencies, such as the hourly traffic volume data. Therefore, this study proposes an LSTM model that employs a power function as the decay function within the forget gate, designed to accommodate long-term patterns and reduce unnecessary information decay in the time series data with significant long-term dependencies.

The memory cell in the forget gate is redefined by the power function to reduce the rate of information decay:

To evaluate the absolute predictive performance of the proposed LSTM model, it was compared against those of linear combination models, multi-step combination models, and convolution neural networks.

Figure 7 depicts the comparative prediction performance of the power-function-based LSTM model against that of the traditional LSTM model, demonstrating enhanced prediction accuracy for the traffic volume.

To further substantiate these findings,

Table 5 presents the prediction performance metrics, demonstrating that the LSTM model achieves an MAE of 0.1288, whereas the power-function-based LSTM model significantly improves this with an MAE of 0.0733. This confirms that the LSTM model developed with the power function exhibits superior predictive performance when compared to the standard LSTM model.

- (5)

Traffic Volume Prediction Using the Power-Function-Based LSTM

Figure 8 depicts the 24 h traffic volume predictions at various random points and times using the power-function-based LSTM model developed in this study.

Table 6 presents the evaluation results of the LSTM model at point 10001 under two scenarios, each assuming different data missing rates. The analysis indicated that scenario 2, with a higher missing rate, outperformed scenario 1, which had a lower missing rate. This suggests that the power-function-based LSTM model can effectively capture long-term trends and uncertainties in the traffic volume data. However, a higher missing rate does not universally ensure better predictions. If the points or times with significant missing data are randomly selected, the prediction performance at a 50% missing rate might actually deteriorate.

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 present the results for each scenario.

5. Model Prediction Performance Verification Results

This study aimed to develop an optimal model to address the missing traffic volume data by comparing and analyzing statistical learning, machine learning, and deep learning models. The SARIMA model was employed to account for seasonality in the traffic volume data, the Prophet model was used for univariate predictions specializing in time series estimation, such as traffic volume, and the LSTM model was utilized to address long-term trends and uncertainties.

Table 7 presents the prediction results based on MAE for the analyzed statistical learning, machine learning, and deep learning models. The verification results indicated that the deep learning models performed the best in predicting traffic volume, followed by machine learning models and statistical learning models. Notably, the LSTM model in deep learning exhibited a higher MAE than the Prophet model in machine learning.

To address this problem, this study proposed the power-function-based LSTM model. This modified LSTM model, utilizing the developed power function, achieved superior performance in correcting and predicting traffic volume compared to the existing models.

Table 8 compares the error rates among the statistical learning, machine learning, and deep learning models, revealing that the power-function-based LSTM model demonstrated lower errors when compared to SARIMA (84.18%), Prophet (78.63%), and LSTM (80.47%). The power-function-based LSTM model recorded an MAE of 0.025, indicating the best performance among all evaluated models.

To further verify the prediction accuracy of the proposed power-function-based LSTM model, the AADT at point 10001 was assumed to have a 50% missing rate when compared to the actual values. The verification results demonstrated a difference of approximately 24 vehicles/day using the existing methods, with an error rate of 0.164%. The power-function-based LSTM model exhibited a difference of approximately four vehicles/day, with an error rate of 0.025%.

The accuracy verification for the AADT indicated a difference of 20 vehicles/day and 8760 vehicles/year, demonstrating that the proposed model significantly outperformed existing methods in correcting traffic volume based on actual values.

Table 9 presents the accuracy verification results of the power-function-based LSTM model.

6. Conclusions

The challenge of uncertainty in traffic volume data persists as an unavoidable issue for next-generation traffic systems. In particular, sensor-based time series traffic volume data, which accumulate vast amounts of real-time information, consistently exhibit anomalies and missing values despite the sophistication of the collection equipment. Therefore, it is crucial to accurately assess the uncertainty of the collected data and execute appropriate correction tasks.

This study applied statistical learning, machine learning, and deep learning models—all primarily utilized for time series algorithms—to develop and evaluate methods that accurately reflect the characteristics of the traffic volume data and enhance the accuracy of correcting and predicting the missing traffic volume data. The key findings of this study are summarized as follows.

First, a statistical learning model, SARIMA (4,1,3)(4,0,3) 12 [

9], effectively captured the periodicity, seasonality, trend, and residual characteristics of traffic volume data. Predictions were also obtained using the Prophet model, a machine-learning-based additive algorithm that performs iterative computations. The SARIMA model predicted traffic volume with an average accuracy of 85%; a comparison of actual values to predicted values exhibited a variation ranging from a minimum of 3.28% to a maximum of 14.59%. For the Prophet model, the performance was evaluated by deleting 10% of the data arbitrarily, revealing an MAE of 0.117, an RMSE of 0.147, and an R

2 of 0.914 for point 10001 and an MAE of 111.687, an RMSE of 158.050, and an R

2 of 0.847 for point 10004.

Second, to address the long-term trends and data uncertainties evident in SARIMA and Prophet models, the performance of the LSTM model—a deep learning approach—was assessed for traffic volume prediction. The results indicated that the LSTM model outperformed the SARIMA model but was less accurate than the Prophet model. To enhance the LSTM model’s performance, this study introduced an improved LSTM model using a power-function-based forget gate memory cell. This adaptation aims to reduce information loss over time and more accurately reflect long-term patterns in time series data with high dependencies.

Third, the traffic volume prediction performance of the proposed power-function-based LSTM model was compared with those of the statistical learning model SARIMA, the machine learning model Prophet, and the deep learning model LSTM. The results confirmed that the proposed model achieved the lowest MAE for correcting and predicting the missing traffic volume.

Therefore, the proposed power-function-based LSTM model is expected to significantly contribute to enhancing the efficiency of traffic surveys and statistics. By improving traffic volume corrections and predictions, it can help prepare accurate and reliable road traffic statistics, which are imperative for national planning and decision making. Moreover, its ability to handle time series data collected in various formats from diverse sources demonstrates its versality and potential applications beyond traffic volume analysis, which is another significant achievement of this study.