BlocklyXR: An Interactive Extended Reality Toolkit for Digital Storytelling

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Motivation and Research Aim

- provide an interactive visual programming environment in which users can create a VR/AR application;

- help users to examine their proposed WebXR with visual previewing content;

- support generating WebXR storytelling applications by providing a real-world 3D map context;

- enable users to control 3D animations in the WebXR application;

- allow users to share their work with others through exporting the WebXR application;

- demonstrate the applicability of BlocklyXR by recreating an existing AR application in geographic information science through the visual programming interface; and

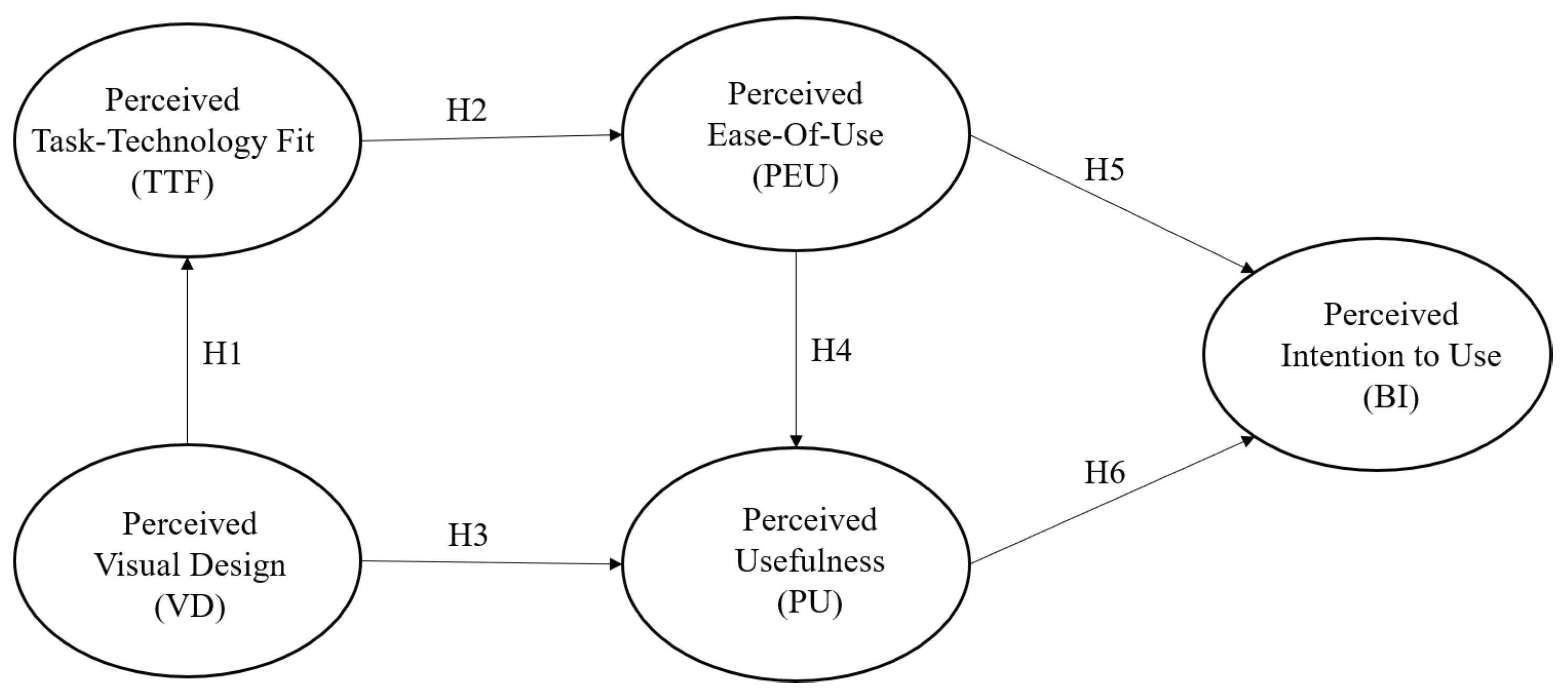

- evaluate BlocklyXR toolkit using the technology acceptance model (TAM) with the following hypotheses:

- -

- Hypotheses 1 (H1).Perceived visual design positively influences perceived task technology fit.

- -

- Hypotheses 2 (H2).Perceived task technology fit positively influences perceived ease of use.

- -

- Hypotheses 3 (H3).Perceived visual design positively influences perceived usefulness.

- -

- Hypotheses 4 (H4).Perceived ease of use positively influences perceived usefulness.

- -

- Hypotheses 5 (H5).Perceived ease of use positively influences intention to use.

- -

- Hypotheses 6 (H6).Perceived usefulness positively influences intention to use.

3. Related Work

4. Materials and Methods

- Task 1 (T1). Enable general users to create VR/AR applications with minimal effort.

- Task 2 (T2). Support users to retrieve and generate real-world data.

- Task 3 (T3). Allow users to examine and control 3D model animations.

- Task 4 (T4). Enable users to test their coding scheme on the visual interface.

- Task 5 (T5). Allow users to share VR/AR apps they have developed with others.

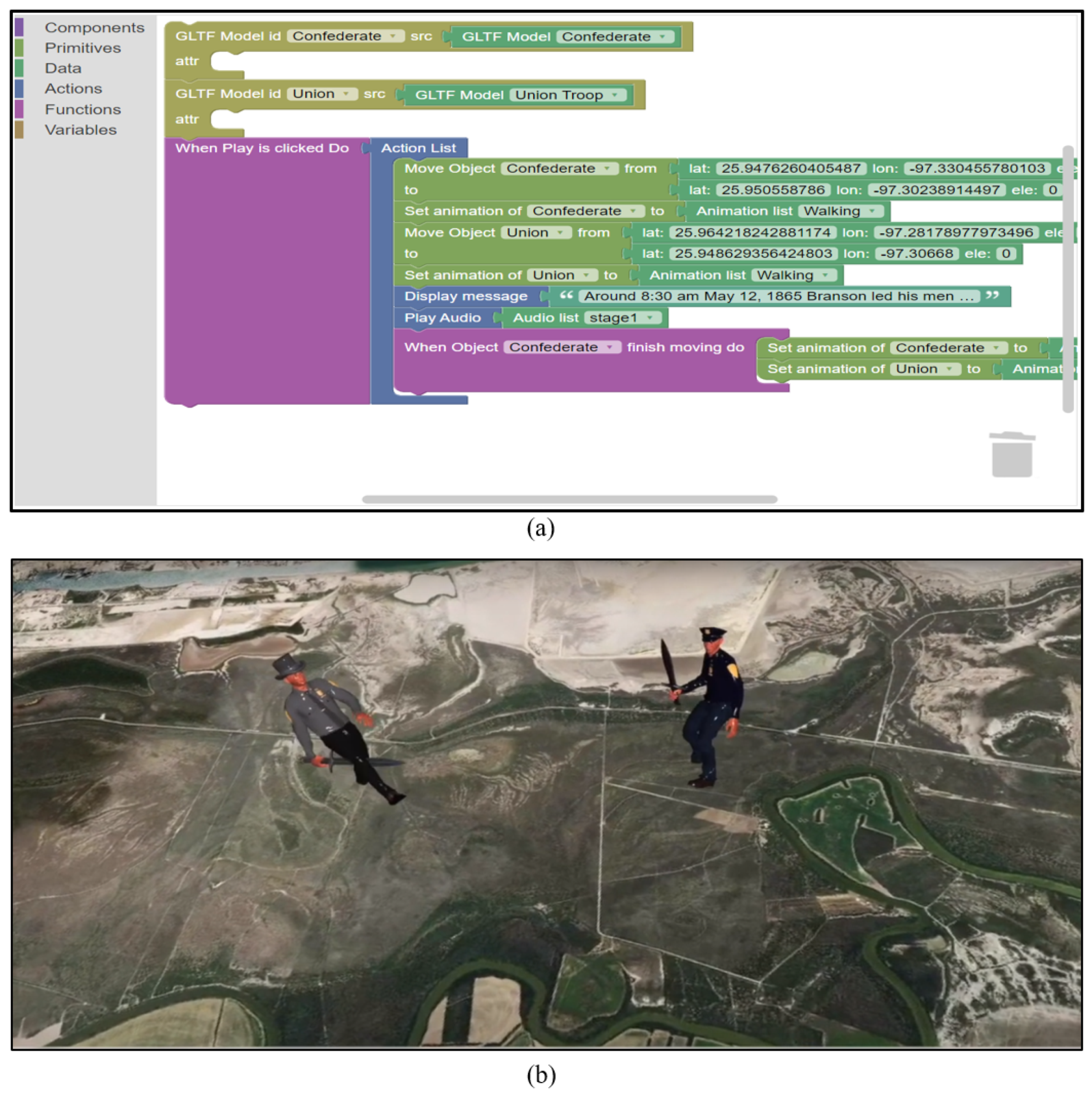

4.1. The Design Editor

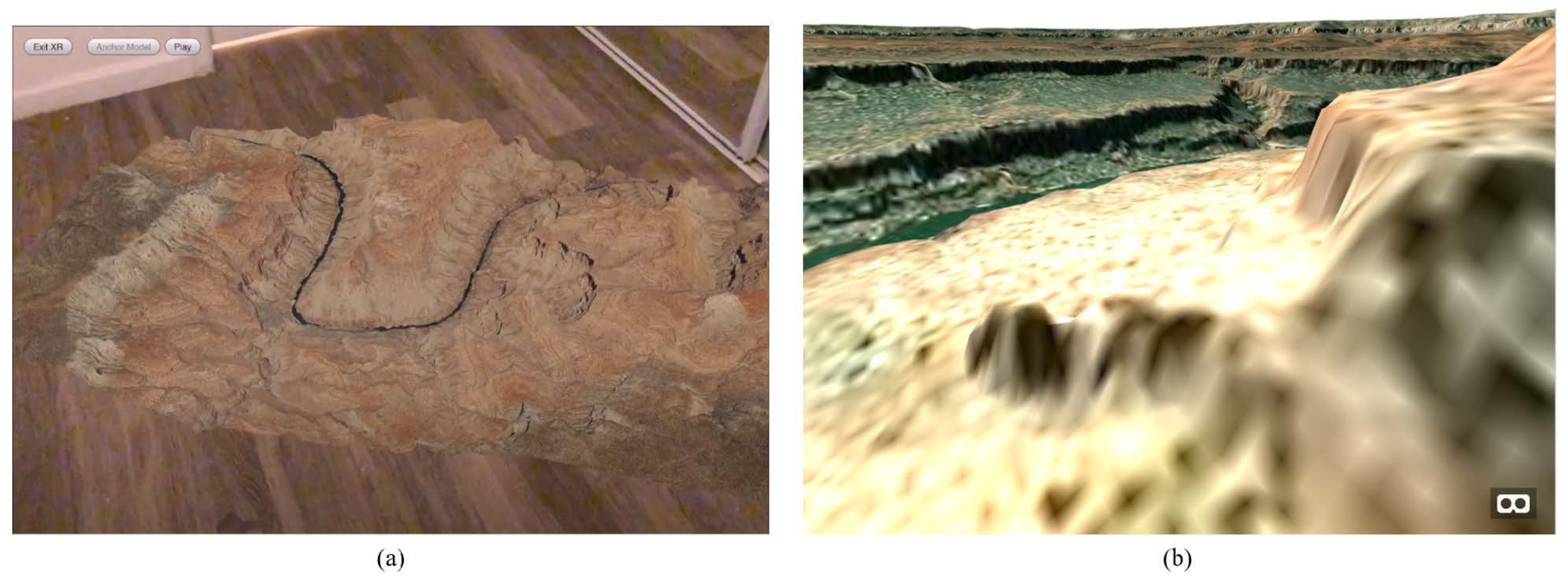

4.2. The Preview Component

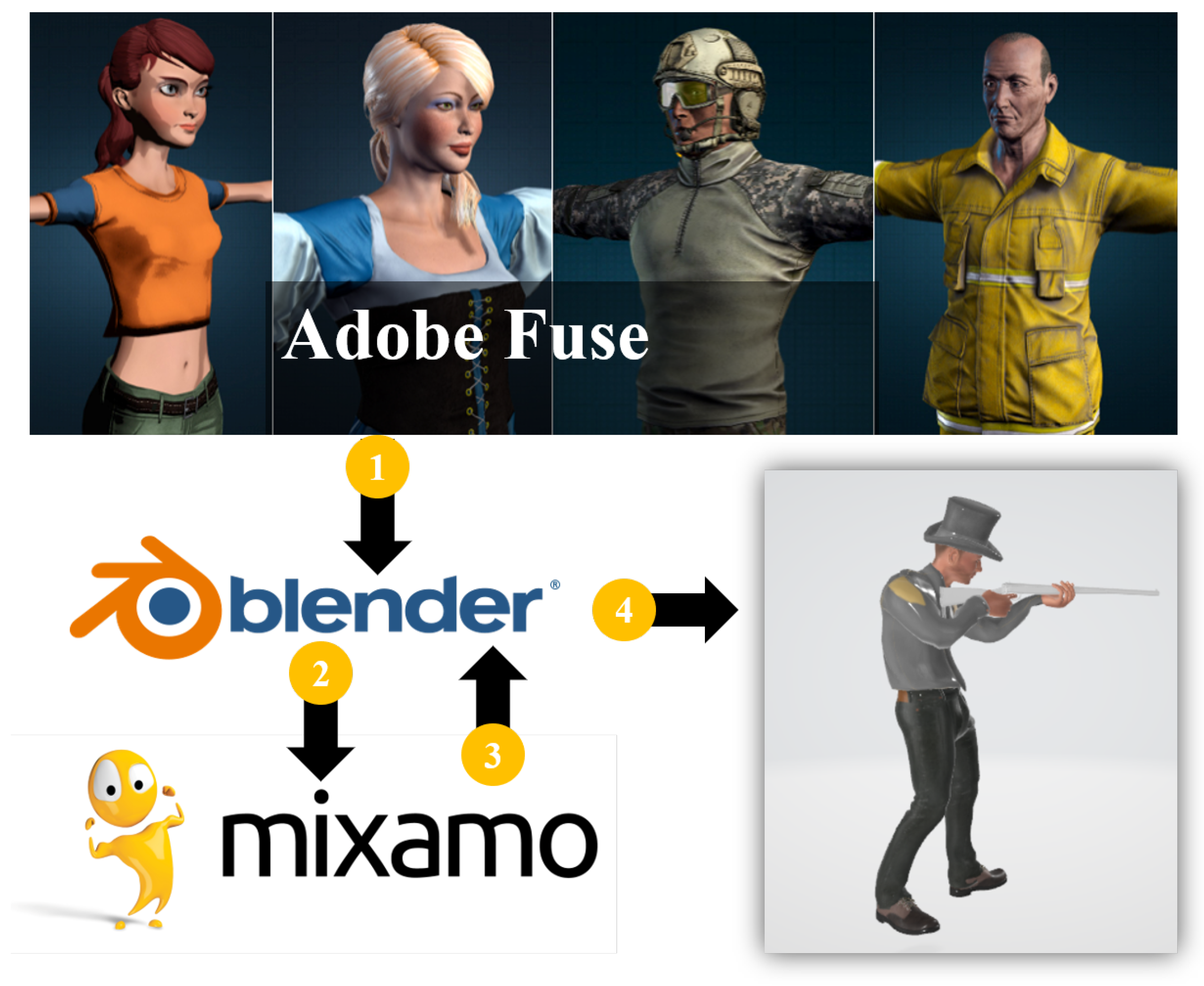

4.3. The Utility Component

4.4. A Use Case

4.5. Evaluation

4.6. Research Model

4.7. Data Collection and Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Qualitative Analysis

5.2. Quantitative Analysis

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arnaldi, B.; Guitton, P.; Moreau, G. Virtual Reality and Augmented Reality: Myths and Realities; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, S.K.; Nee, A.Y.C. Virtual and Augmented Reality Applications in Manufacturing; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, H.; Kim, Y.O. Virtual reality and augmented reality in plastic surgery: A review. Arch. Plast. Surg. 2017, 44, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherman, W.R.; Craig, A.B. Understanding Virtual Reality; Morgan Kauffman: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Carmigniani, J.; Furht, B.; Anisetti, M.; Ceravolo, P.; Damiani, E.; Ivkovic, M. Augmented reality technologies, systems and applications. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2011, 51, 341–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; LaFemina, P.; Wallgrün, J.O.; Oprean, D.; Klippel, A. iVR for the geosciences. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Virtual Reality Workshop on K-12 Embodied Learning through Virtual & Augmented Reality (KELVAR), Los Angeles, CA, USA, 19 March 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Moody, L.; Waterworth, A.; McCarthy, A.D.; Harley, P.J.; Smallwood, R.H. The feasibility of a mixed reality surgical training environment. Virtual Real. 2008, 12, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y. Application of the Architectural Animation Virtual Technology in the Landscape Architecture Design. Cyber Secur. Intell. Anal. 2019, 928, 339. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S.; Devreaux, P.; Scribner, D.; Grynovicki, J.; Grazaitis, P. Megacity: A Collaborative Virtual Reality Environment for Emergency Response, Training, and Decision Making. Electron. Imaging 2017, 2017, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanco, F.; Tanasi, D.; Allegra, D.; Milotta, F.L.M.; Lamagna, G.; Monterosso, G. Virtual anastylosis of Greek sculpture as museum policy for public outreach and cognitive accessibility. J. Electron. Imaging 2017, 26, 011025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Hou, G.; Wang, Z. Virtual reality and its application in military. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2018; Volume 170, p. 032155. [Google Scholar]

- Bruno, F.; Barbieri, L.; Marino, E.; Muzzupappa, M.; D’Oriano, L.; Colacino, B. An augmented reality tool to detect and annotate design variations in an Industry 4.0 approach. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 105, 875–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.; Nguyen, V.T.; Yoo, S.C.; Kim, S.; Park, S.; Currie, M. PalmitoAR: The Last Battle of the US Civil War Reenacted Using Augmented Reality. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norouzi, N.; Bruder, G.; Belna, B.; Mutter, S.; Turgut, D.; Welch, G. A systematic review of the convergence of augmented reality, intelligent virtual agents, and the internet of things. In Artificial Intelligence in IoT; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Linowes, J.; Babilinski, K. Augmented Reality for Developers: Build Practical Augmented Reality Applications with Unity, ARCore, ARKit, and Vuforia; Packt Publishing Ltd.: Birmingham, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardes, S.; Madden, M.; Knight, A.; Neel, N.; Morgan, N.; Cameron, K.; Knox, J. A multi-component system for data acquisition and visualization in the geosciences based on uavs, augmented and virtual reality. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2018, XLII-4, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavish, N.; Gutiérrez, T.; Webel, S.; Rodríguez, J.; Peveri, M.; Bockholt, U.; Tecchia, F. Evaluating virtual reality and augmented reality training for industrial maintenance and assembly tasks. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2015, 23, 778–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.T.; Hite, R.; Dang, T. Learners’ technological acceptance of vr content development: A sequential 3-part use case study of diverse post-secondary students. Int. J. Semant. Comput. 2019, 13, 343–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, H. ARToolKit: Library for Vision-Based augmented reality. IEICE PRMU 2002, 6, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Danchilla, B. Three.js framework. In Beginning WebGL for HTML5; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 173–203. [Google Scholar]

- Mozilla. A Web Framework for Building Virtual Reality Experiences. 2019. Available online: https://aframe.io (accessed on 23 January 2020).

- Moreau-Mathis, J. Babylon. js Essentials; Packt Publishing Ltd.: Birmingham, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, V.T.; Hite, R.; Dang, T. Web-Based Virtual Reality Development in Classroom: From Learner’s Perspectives. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Virtual Reality (AIVR), Taichung, Taiwan, 10–12 December 2018; pp. 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.T.; Jung, K.; Dang, T. Creating Virtual Reality and Augmented Reality Development in Classroom: Is it a Hype? In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Virtual Reality (AIVR), San Diego, CA, USA, 9–11 December 2019; pp. 212–2125. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, V.T.; Zhang, Y.; Jung, K.; Xing, W.; Dang, T. VRASP: A Virtual Reality Environment for Learning Answer Set Programming. In International Symposium on Practical Aspects of Declarative Languages; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 82–91. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, K.; Nguyen, V.T.; Diana, P.; Seung-Chul, Y. Meet the Virtual Jeju Dol Harubang—The Mixed VR/AR Application for Cultural Immersion in Korea’s Main Heritage. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinet, F.; Arnaud, R.; Parisi, T.; Cozzi, P. gltf: Designing an open-standard runtime asset format. GPU Pro 2014, 5, 375–392. [Google Scholar]

- Radu, I.; MacIntyre, B. Augmented-reality scratch: A children’s authoring environment for augmented-reality experiences. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Interaction Design and Children, Como, Italy, 3–5 June 2009; pp. 210–213. [Google Scholar]

- CoSpaces. Make AR & VR in the Classroom. 2020. Available online: https://cospaces.io/edu/ (accessed on 5 April 2020).

- Mota, J.M.; Ruiz-Rube, I.; Dodero, J.M.; Arnedillo-Sánchez, I. Augmented reality mobile app development for all. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2018, 65, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnick, M.; Maloney, J.; Monroy-Hernández, A.; Rusk, N.; Eastmond, E.; Brennan, K.; Millner, A.; Rosenbaum, E.; Silver, J.; Silverman, B.; et al. Scratch: Programming for all. Commun. ACM 2009, 52, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology. MIT App Inventor. 2020. Available online: http://appinventor.mit.edu/ (accessed on 19 June 2020).

- Inc, G. Blockly: A JavaScript Library for Building Visual Programming Editors. 2020. Available online: https://developers.google.com/blockly (accessed on 5 April 2020).

- Clarke, N.I. Through the Screen and into the World: Augmented Reality Components with MIT App Inventor. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Rube, I.; Mota, J.M.; Person, T.; Corral, J.M.R.; Dodero, J.M. Block-based development of mobile learning experiences for the Internet of Things. Sensors 2019, 19, 5467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, A.; Shapiro, R.B.; de Halleux, J.; Ball, T. ARcadia: A rapid prototyping platform for real-time tangible interfaces. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 21–26 April 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, V.T.; Jung, K.; Dang, T. BlocklyAR: A Visual Programming Interface for Creating Augmented Reality Experiences. Electronics 2020, 9, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schez-Sobrino, S.; Vallejo, D.; Glez-Morcillo, C.; Redondo, M.Á.; Castro-Schez, J.J. RoboTIC: A serious game based on augmented reality for learning programming. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2020, 79, 34079–34099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rienow, A.; Lindner, C.; Dedring, T.; Hodam, H.; Ortwein, A.; Schultz, J.; Selg, F.; Staar, K.; Jürgens, C. Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality Applications Based on Satellite-Borne and ISS-Borne Remote Sensing Data for School Lessons. Pfg-J. Photogramm. Remote. Sens. Geoinf. Sci. 2020, 88, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersten, T.P.; Tschirschwitz, F.; Deggim, S. Development of a virtual museum including a 4D presentation of building history in virtual reality. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2017, 42, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfahlani, S.S. Mixed reality and remote sensing application of unmanned aerial vehicle in fire and smoke detection. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2019, 15, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapbox. Mapbox GL JS. 2020. Available online: https://docs.mapbox.com/mapbox-gl-js/api/ (accessed on 18 June 2020).

- W3C Immersive Web Working Group. WebXR Device API. 2020. Available online: https://immersive-web.github.io/webxr/ (accessed on 18 June 2020).

- Anonymous. BlocklyXR: Create a Storytelling with the Visual Mixed Reality Toolkit. 2020. Available online: https://youtu.be/Gj2NmmL0hc4 (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Munzner, T. Visualization Analysis and Design; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, V.T.; Jung, K.; Yoo, S.; Kim, S.; Park, S.; Currie, M. Civil War Battlefield Experience: Historical Event Simulation using Augmented Reality Technology. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Virtual Reality (AIVR), San Diego, CA, USA, 9–11 December 2019; pp. 294–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. A Technology Acceptance Model for Empirically Testing New End-User Information Systems: Theory and Results. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Marangunić, N.; Granić, A. Technology acceptance model: A literature review from 1986 to 2013. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2015, 14, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost, H. A review of technology acceptance and adoption models and theories. Procedia Manuf. 2018, 22, 960–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodhue, D.L.; Thompson, R.L. Task-technology fit and individual performance. MIS Q. 1995, 19, 213–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dishaw, M.T.; Strong, D.M. Extending the technology acceptance model with task–technology fit constructs. Inf. Manag. 1999, 36, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.M.; Yeh, Y.S. Increasing trust in mobile commerce through design aesthetics. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 673–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhagen, T.; Feldberg, F.; van den Hooff, B.; Meents, S.; Merikivi, J. Understanding users’ motivations to engage in virtual worlds: A multipurpose model and empirical testing. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 484–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, D. Acceptance of mobile mental health treatment applications. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2016, 98, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.; Takane, Y. Generalized Structured Component Analysis: A Component-Based Approach to Structural Equation Modeling; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, H.; Takane, Y.; Jung, K. Generalized structured component analysis with uniqueness terms for accommodating measurement error. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, H.; Cho, G.; Jung, K.; Falk, C.; Flake, J.; Jin, M. An Approach to Structural Equation Modeling with Both Factors and Components: Integrated Generalized Structured Component Analysis. 2020. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2020-51893-001 (accessed on 22 July 2020).

- Hwang, H.; Malhotra, N.K.; Kim, Y.; Tomiuk, M.A.; Hong, S. A comparative study on parameter recovery of three approaches to structural equation modeling. J. Mark. Res. 2010, 47, 699–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.; Panko, P.; Lee, J.; Hwang, H. A comparative study on the performance of GSCA and CSA in parameter recovery for structural equation models with ordinal observed variables. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, K.; Lee, J.; Gupta, V.; Cho, G. Comparison of Bootstrap Confidence Interval Methods for GSCA Using a Monte Carlo Simulation. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, H.; Jung, K.; Kim, S. WEB GESCA. 2019. Available online: http://sem-gesca.com/webgesca (accessed on 22 July 2020).

- Rese, A.; Baier, D.; Geyer-Schulz, A.; Schreiber, S. How augmented reality apps are accepted by consumers: A comparative analysis using scales and opinions. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 124, 306–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauschnabel, P.A.; Felix, R.; Hinsch, C. Augmented reality marketing: How mobile AR-apps can improve brands through inspiration. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 49, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilken, T.; de Ruyter, K.; Chylinski, M.; Mahr, D.; Keeling, D.I. Augmenting the eye of the beholder: Exploring the strategic potential of augmented reality to enhance online service experiences. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 884–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.; Xu, X. Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.D.; Rana, N.P.; Dwivedi, Y.K. The unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT): A literature review. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2015, 28, 443–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google. Google Maps Platform. 2020. Available online: https://cloud.google.com/maps-platform (accessed on 25 July 2020).

- OSM Foundation. OpenStreetMap. 2020. Available online: https://www.openstreetmap.org/about (accessed on 25 July 2020).

- Cesium. Changing How the World Views 3D. 2020. Available online: https://cesium.com/ (accessed on 25 July 2020).

- Mapbox. Tabletop AR. 2020. Available online: https://docs.mapbox.com/unity/maps/examples/tabletop-ar/ (accessed on 5 April 2020).

- Maher, M.M. Lining Up Data in ArcGIS: A Guide to Map Projections; Esri Press: Redlands, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- WebAssembly. World Wide Web Consortium. 2020. Available online: https://webassembly.org/ (accessed on 25 July 2020).

- Nguyen, V.T.; Dang, T. Setting up Virtual Reality and Augmented Reality Learning Environment in Unity. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality (ISMAR-Adjunct), Nantes, France, 9–13 October 2017; pp. 315–320. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, J.H.; Murray, J.H. Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, H. Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Forte, M.; Kurillo, G. Cyberarchaeology: Experimenting with teleimmersive archaeology. In Proceedings of the 2010 16th International Conference on Virtual Systems and Multimedia, Seoul, Korea, 13–20 October 2010; pp. 155–162. [Google Scholar]

- Liarokapis, F.; Greatbatch, I.; Mountain, D.; Gunesh, A.; Brujic-Okretic, V.; Raper, J. Mobile augmented reality techniques for geovisualisation. In Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Information Visualisation (IV’05), London, UK, 6–8 July 2005; pp. 745–751. [Google Scholar]

- Ocampo, A.; Palaoag, T. Improving Tourism Experiences in Open Data Environment with Mobile Augmented Reality: Needs and Challenges. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Technology and Digital Applications, Istanbul, Turkey, 16–17 April 2019; Volume 483, p. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Heijden, H. User acceptance of hedonic information systems. MIS Q. 2004, 28, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Source |

|---|---|

| Perceived Task Technology Fit | [54] |

| (TTF1) BlocklyXR (A visual programming interface) is adequate for a visual programming toolkit to create extended reality experiences. | |

| (TTF2) BlocklyXR is compatible with the task of controlling virtual objects. | |

| (TTF3) BlocklyXR fits the task well (i.e., visual programming to create extended reality experiences). | |

| (TTF4) BlocklyXR is sufficient for a visual programming toolkit to create extended reality experiences. | |

| Perceived Visual Design | [53] |

| (VD1) The visual design of BlocklyXR is appealing. | |

| (VD2) The size of the 3D virtual objects is adequate. | |

| (VD3) The layout structure is appropriate. | |

| Perceived Usefulness | [55] |

| (PU1) Using BlocklyXR would improve my knowledge in visual programming skills to create extended reality experiences. | |

| (PU2) Using BlocklyXR, I would accomplish tasks more quickly (i.e., visual programming to create extended reality experiences). | |

| (PU3) Using BlocklyXR would increase my interest in a visual programming toolkit to create extended reality experiences. | |

| (PU4) Using BlocklyXR would enhance my effectiveness on the task (i.e., visual programming to create extended reality experiences). | |

| (PU5) Using BlocklyXR would make it easier to do my task (i.e., visual programming to create extended reality experiences). | |

| Perceived Ease of Use | [55] |

| (PEU1) Learning to use the visual programming toolkit would be easy for me. | |

| (PEU2) I would find it easy to get the visual programming toolkit to do what I want it to do. | |

| (PEU3) My interaction with the visual programming toolkit would be clear and understandable. | |

| (PEU4) I would find the visual programming toolkit to be flexible to interact with. | |

| (PEU5) It would be easy for me to become skillful at using the visual programming toolkit. | |

| (PEU6) I would find the visual programming toolkit easy to use. | |

| Intention to Use | [55] |

| (BI1) I intend to use the visual programming toolkit in the near future. | |

| (BI2) I intend to check the availability of the visual programming toolkit in the near future. |

| Variable | Category | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 54 | 73.97 |

| Female | 19 | 26.03 | |

| English as a First Language | Yes | 54 | 73.97 |

| No | 19 | 26.03 | |

| Ethnic heritage | Asian | 42 | 57.53 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 2 | 2.74 | |

| Caucasian/White | 22 | 30.14 | |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 2 | 2.74 | |

| African American/Black | 4 | 5.48 | |

| Total | 73 | 100 |

| Construct | Item | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Task Technology Fit | TTF1 | 4.195 | 0.466 |

| TTF2 | 4.260 | 0.764 | |

| TTF3 | 4.178 | 0.903 | |

| TTF4 | 4.014 | 0.979 | |

| Perceived Visual Design | VD1 | 4.096 | 0.945 |

| VD2 | 4.151 | 0.892 | |

| VD3 | 4.110 | 0.936 | |

| Perceived Usefulness | PU1 | 4.055 | 1.066 |

| PU2 | 4.055 | 0.970 | |

| PU3 | 4.041 | 1.060 | |

| PU4 | 4.178 | 0.991 | |

| PU5 | 4.123 | 1.013 | |

| Perceived Ease of Use | PEU1 | 4.068 | 0.933 |

| PEU2 | 3.863 | 0.962 | |

| PEU3 | 4.068 | 1.045 | |

| PEU4 | 3.904 | 0.974 | |

| PEU5 | 4.068 | 0.918 | |

| PEU6 | 3.918 | 1.010 | |

| Intention to Use | BI1 | 3.658 | 1.157 |

| BI2 | 3.671 | 1.281 |

| Construct | Item | Dillon-Goldstein’s Rho | Average Variance Extracted |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Task Technology Fit (TTF) | 4 | 0.881 | 0.652 |

| Perceived Visual Design (VD) | 3 | 0.790 | 0.566 |

| Perceived Usefulness (PU) | 5 | 0.925 | 0.713 |

| Perceived Easy of Use (PEU) | 6 | 0.883 | 0.561 |

| Intention to Use (BI) | 2 | 0.920 | 0.852 |

| Estimate | SE | 95% CI_LB | 95% CI_UB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TTF1 | 0.855 | 0.051 | 0.733 | 0.924 |

| TTF2 | 0.655 | 0.079 | 0.486 | 0.778 |

| TTF3 | 0.850 | 0.046 | 0.738 | 0.906 |

| TTF4 | 0.852 | 0.035 | 0.766 | 0.900 |

| VD1 | 0.885 | 0.027 | 0.816 | 0.920 |

| VD2 | 0.530 | 0.162 | 0.167 | 0.756 |

| VD3 | 0.795 | 0.068 | 0.666 | 0.882 |

| PU1 | 0.836 | 0.049 | 0.723 | 0.898 |

| PU2 | 0.784 | 0.070 | 0.615 | 0.866 |

| PU3 | 0.898 | 0.031 | 0.815 | 0.934 |

| PU4 | 0.827 | 0.057 | 0.658 | 0.888 |

| PU5 | 0.872 | 0.034 | 0.790 | 0.925 |

| PEU1 | 0.732 | 0.112 | 0.512 | 0.899 |

| PEU2 | 0.857 | 0.059 | 0.686 | 0.924 |

| PEU3 | 0.782 | 0.056 | 0.648 | 0.866 |

| PEU4 | 0.762 | 0.067 | 0.607 | 0.871 |

| PEU5 | 0.578 | 0.163 | 0.196 | 0.787 |

| PEU6 | 0.756 | 0.075 | 0.568 | 0.880 |

| BI1 | 0.897 | 0.032 | 0.807 | 0.938 |

| BI2 | 0.948 | 0.017 | 0.903 | 0.977 |

| Estimates | Std.Error | 95% CI_LB | 95% CI_UB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VD → TTF | 0.715 * | 0.064 | 0.616 | 0.831 |

| TTF → PEU | 0.597 * | 0.109 | 0.340 | 0.767 |

| VD → PU | 0.492 * | 0.118 | 0.215 | 0.656 |

| PEU → PU | 0.319 * | 0.120 | 0.094 | 0.560 |

| PEU → BI | 0.195 | 0.167 | −0.111 | 0.554 |

| PU → BI | 0.604 * | 0.140 | 0.317 | 0.856 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jung, K.; Nguyen, V.T.; Lee, J. BlocklyXR: An Interactive Extended Reality Toolkit for Digital Storytelling. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1073. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11031073

Jung K, Nguyen VT, Lee J. BlocklyXR: An Interactive Extended Reality Toolkit for Digital Storytelling. Applied Sciences. 2021; 11(3):1073. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11031073

Chicago/Turabian StyleJung, Kwanghee, Vinh T. Nguyen, and Jaehoon Lee. 2021. "BlocklyXR: An Interactive Extended Reality Toolkit for Digital Storytelling" Applied Sciences 11, no. 3: 1073. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11031073

APA StyleJung, K., Nguyen, V. T., & Lee, J. (2021). BlocklyXR: An Interactive Extended Reality Toolkit for Digital Storytelling. Applied Sciences, 11(3), 1073. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11031073