Abstract

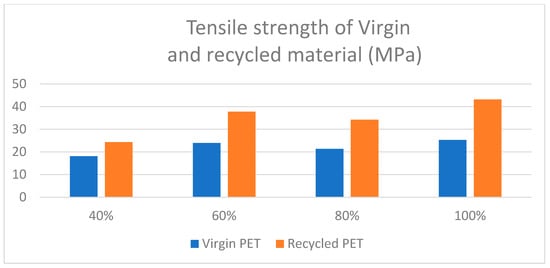

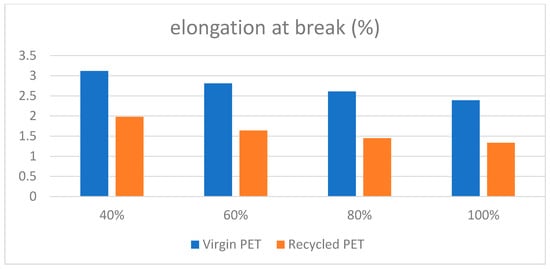

Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM) is the most common 3D printing technology. An object formed through continuous layering until completion is known as an additive process while other processes with different methods are also relevant. In this paper, mechanical properties were analysed using two distinct kinds of printed polyethylene terephthalate (PET) as tensile test specimens. The materials used consist of recycled PET and virgin PET. An assessment of all the forty test pieces of both kinds of PET was undertaken. A comparison of the test samples’ tensile strength values, difference in stress-strain curves, and elongation at break was also carried out. The reasoning behind the fracturing of test pieces that printed with different settings is presented in part by the depiction of the fractured specimens following the tensile test. An optimal route was revealed to be 3D printing with recycled PET, as per the mechanical testing. The hardness of the recycled filament decreased to 6%, while the tensile strength and shear strength increased to 14.7 and 2.8%, respectively. Nonetheless, no changes occurred to the tensile modulus elasticity. Despite notable differences being observed in the results of the recycled PET filament, no substantial differences were found prior or post-recycling in the mechanical properties of the PET filament. In conclusion, the demand for improved recycled 3D printing filament technologies is heightened due to the comparable mechanical features of the specimens of both the 3D printed recycled and virgin materials. With tensile strength figures reaching as high as 43.15MPa at Recycled PET and 3.12% being the greatest elongation at 40% Recycled PET, 100% Recycled is the ideal printing setting.

1. Introduction

Waste components produced in the additive process reveal various phenotypes. Low cost, rapid, and stellar accessibility are among the strengths of additive manufacturing. Additionally, parts that are usually disposed can be utilized, as well. Acrylonitrile butadiene styrene is one of the ingredients within plant material or petroleum that is used in 3D thermoplastic [1,2,3,4].

The easy-to-use nature of the technology is one of its greatest strengths, where the general production process and layering of materials using a computer-guided tool is made simple. By streamlining the processes, tools, and parts involved, needless effort and toil by the user is averted while giving an ample scope for designers to create. These improvements profoundly impact production costs within mechanization and line production, elevating the profit margin by USD 5 billion by mitigating inflated production costs. From the opening quarter of 2020, 3D printing was forecasted to increase to between USD 7 and 23 billion [5,6], while the global market of 3D printing is predicted to jump to USD 51.77 billion by 2026. In addition, 200 million users are forecasted to be reached due to the demand of injection moulding plastic. The continuously evolving technology and adaptability of 3D printing has seen it grow in the present market, contrasting with injection moulding [7].

Nevertheless, regarding quality and the standardization of the finished product, the injection moulding process remains superior to 3D printing. While 3D printing can create roughly 5000 distinct sizes and shapes for components, it is typically used for small production units in competitive settings. The standard practices and technology implemented by a specific organisation or country determine which materials are used for 3D printing. Whether making bottle caps, jugs or plumbing pipes, using HDPE or bottle manufacturing and fiber using PET, plastic wastes are usually recyclable. PET is considered the optimal recyclable material when 3D printing. Prior to the extrusion process, the PET is dried. HDPE, ABS, and PET are moulded into pellets after being shredded when a plastic pellet formation is sought. While sheets are frequently constructed using injection moulds, the creation of 3D printers occurs through laments being formed after additional processing of the pellets. Similar to any manufacturing technology, difficulties and obstacles persist, yet the various methods mentioned to recycle plastics are both affordable and easy to use [8]. Through the presence of polylactic acid, losses to the tensile strength were found, yet were negligible after the extruded PET was recycled over 10 times. A marginal loss in the mechanical properties of polypropylene (PP) and polybutylene terephthalate (PBT) was found after mixing the polymers at distinct ratios. Prior to use in component fabrication, the mechanical properties of a 3D printed PET filament remained unaffected after being recycled five times, as per a study in the field. Nonetheless, at the fracture point, a 10% reduction in elongation was observed [9].

Gases are released at high temperatures due to 3D printing thermoplastic. Hydrogen cyanide, carbon monoxide, and other instable organics were identified as outputs when using ABS [10]. There are potential health risks when using ABS which emits a higher quantity of ultrafine particles than the PET filament. Contaminates and pollutants linked to health risks are a principal cause of this. Prior to further research, these risks should be taken into account. Thus, the process of 3D printing must include an adequate ventilation system to avert these risks. Presently, the next generations of 3D printers may include HEPA filters to mitigate these risks, as these filters are tried and tested within desktops in the current market [11].

Sixty percent of plastic materials stemming from synthetic fibers meet the world-wide requirement of 30%. Polyethene (PE) and polypropylene (PP) are the largest usable polymers, while PET comes third, also known as polyester, making up 18% of the global polymer production [12]. In 1973, Nathaniel Wyeth removed the patent of the first PET bottle. Solar cells and thin films are additional materials made using PET [13].

Evaluating the mechanical properties of the samples created from the virgin PET filament is the aim of this paper. The original printed 3D samples are recycled to produce the specimens made by the PET filament which, in turn, are compared with the results of the study. The pliancy of PET when recycled was the determining factor leading to its selection in this paper.

2. Materials and Methods

The plastic PET bottles were grinded in order to prepare the accumulated waste of PET plastic. Three principal stages mark the grinding of PET plastic accumulation. The first involves collecting the plastic waste, the second consists of drying the bottles, and the third involves grinding and shredding the bottles to a particular particle size. FKF Zrt, a Budapest-based plastic recycling company carried out the process of grinding. The distinct kinds of selective waste recycled by the company are illustrated in Table 1 below. The monthly sorting of incoming waste serves as the basis for the statistics.

Table 1.

Ratio and types of collected selective waste during the first trimester 2018.

For the experimental work, coloured and clean PET materials were chosen. The Department of Mechanical Engineering at Szent Istvan University carried out the mechanical strength testing of 3D printed parts. Prior to the extrusion process, the sample was dried and thermal properties of the material are indicated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Thermal properties of PET.

After obtaining the samples from the 3D printing Free Dee printing solutions, the laboratory of mechanical engineering in Szent Istvan University carried out the test.

Prior to the drying and shredding of the material using an extrusion machine as shown in Figure 1, the PET was also dried for extrusion, in order to adequately prepare the sample. Extrusion then occurred once thoroughly dry. The extrusion of the PET was enabled through the use of the next filament extruder.

Figure 1.

Sample of extrusion machine during the preparation of the specimens.

The speed of the fan and temperature remained constant, while the shredding of the material occurred using three distinct diameters. Once three tests were completed, the measurement was ready. The features of the daily test are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Setting and parameters used during the preparation.

The test commences with measuring the filaments in intervals of 1 m as well as the diameter of the recycled PET. This allows an examination of the filament quality control. Subsequently, the thermal properties are examined after identifying the melting points and the cross-section and surface of the materials are tested. The tensile testing for the raw materials is part of the second test.

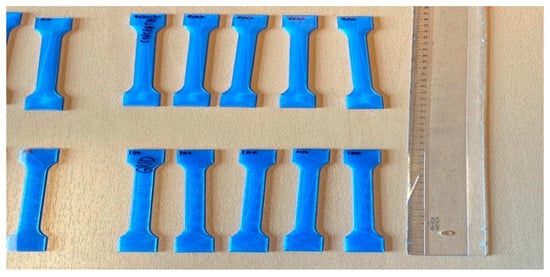

In line with the Iso 527–1:2012 standard of the American Society of Testing Materials (ASTM), the tensile specimens were created (as illustrated in Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Testing materials standard for the specimens.

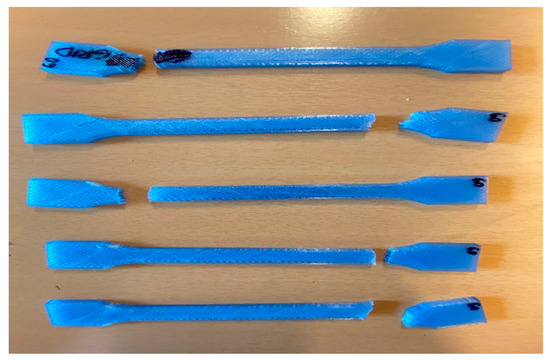

The virgin PET filament with a diameter of 1.75 mm enabled the manufacturing of the original test samples. A digital micrometer with 0.01 mm accuracy was used to assess the length and width of the shear specimens after the specimens were generated at 210 °C with a nozzle of 0.4 mm. At a head travel speed of 5 mm per min, the Testometrinc Zwick/Roel Z100 was used to carry out the tensile testing, as seen in Figure 3, after the tensile test, a sample of final shape of virgin Pet specimen is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Testing tensile specimens, Testometric.

Figure 4.

Sample of specimens after the tensile test (virgin PET).

Tensile properties including tensile yield strength and tensile modulus of elasticity were cited in Table 4.

Table 4.

Tensile properties of virgin versus recycled polyethylene terephthalate 3D printed specimens.

3. Results

3.1. Tensile Properties for Virgin and Recycled Polyethylene Terephthalate

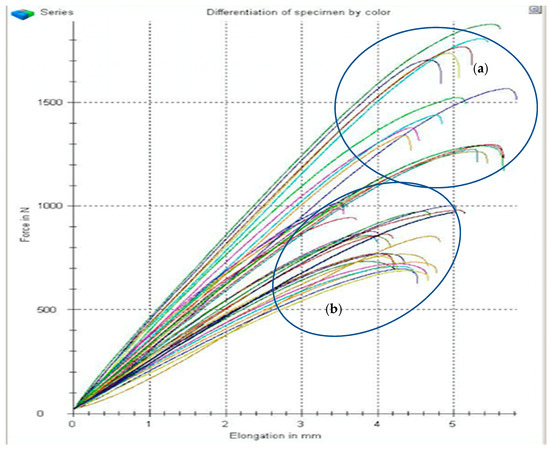

Extensometers for polyethylene material were not needed as the extension/strain ratio was sufficient to estimate strain. The PET tensile specimens’ strain/extension ratio was 0.243 after plotting the strain from extensometers against the crosshead extension. The strain from the crosshead extension, which forms part of the modulus calculations, were estimated via the aforementioned method. Figure 5 show the curves of the relation between force and elongation of both recycled and virgin material. The average tensile strength and elongation at break of the virgin and recycled materials were illustrated in Table 5 and Table 6 and presents in Figure 6 for the recycled material and Figure 7 for the virgin one.

Figure 5.

Tensile elongation of a recycled (a) and virgin (b) 3D printed PET.

Table 5.

Tensile strength and elongation at break of virgin PET filament.

Table 6.

Tensile strength and elongation at break of recycled PET filament.

Figure 6.

Tensile strength of a recycled and virgin 3D printed PET.

Figure 7.

Elongation at a break of a recycled and virgin 3D printed PET.

Distinct extensometers were not used and the elongation and load were not recorded. The hardness of the middle shear samples was evaluated using the shore D digital durometer. Due to the chance that the needle could fall into a small depression in the surface, the highest value was documented and the hardness was measured on four occasions.

3.2. Shear Strength Properties for Virgin and Recycled Polyethylene Terephthalate

The properties of shear, tensile, and hardness served as the parameters for both the recycled and virgin test samples, and the results were obtained with this focus. The tensile modulus of the elasticity and the yield strength of the 40 virgin specimens and 40 recycled specimens were examined. Table 7 and Table 8 illustrates the results. Establishing an offset value of 0.11 mm enabled the analysis of the yield point. The tensile specimens were used to form a pre-set relationship between the strain and the crosshead extension which, in turn, allowed the tensile modulus to be measured. An estimate of the strain can be deduced without the extensometer use by analysing the extension/strain ratio and utilizing the reference.

Table 7.

Shear strength of virgin versus recycled polylactic acid 3D printed specimens.

Table 8.

The hardness of virgin versus recycled polylactic acid 3D printed specimens.

3.3. Hardness Properties for Virgin and Recycled Polyethylene Terephthalate

While the variance between the recycled and original is evident, the results are very encouraging. However, it is important to note the 3–9% decrease in the average mechanical properties of the recycled samples in comparison with the virgin samples. Additionally, the increase in standard deviation signifies an increased variability of the recycled material’s results.

The capacity to mix plastic wastes and require less energy are two areas that must be improved upon within chemical recycling in order to become more sustainable. The use, technological development, and demand of polymers that cannot be recycled should also lessen. Plastic solid waste can only be recycled via mechanical recycling, as per a review of the literature. Through melting, shredding, and re-moulding after washing, organic residue is removed from the polymer and the resultant material becomes ready for manufacturing again once it is compatible with virgin plastic. Chemical recycling refers to the method distinct from standard mechanical recycling which selectively produces fuels, gases or waxes using catalyst, otherwise known as pyrolysis. The present technologies involved in this process exact at high energy cost, which impedes prevalent use. The burning of materials and the resultant collection of energy is another option known as incineration. The inability to reuse or recapitalize are drawbacks of this method, yet its strengths lie in its convenience as mixed wastes require no sorting. While sophisticated laboratories test recycled plastic waste, incineration is not energy efficient.

A majority of tests taking place in laboratories occurred in co-operation with the FKF Zrt, of note to the context of this research project. The organisation owns a sophisticated laboratory for testing of recycled plastic waste and closely co-operates with the faculty of mechanical engineering. The impressive properties of the conductive antistatic ABS were highlighted in the previous test, demonstrating its exceptional resistance to high and low temperatures, its impact resistance with dimensional stability, exceptional mechanical strength, and high flow creep resistance. Better even than the ABS was the PET filament. The stoppage of the material flow was found to be the principal issue linked to the rPET extrusion. The HDPE filament would thin and then fracture as the extrudate gradually failed to come out of the die in the middle of the extrusion. Thus, complications were present in the HDPE extrusion.

Various elements caused the reduction in hardness, tensile strength, and other properties. One such element could be the recycled filament’s properties degrading and other factors include the limit in the inter-layer adhesion and the extrusion interruptions when 3D printing. This paper does not include the individual filament properties as they could not be examined. Flaws in the samples and recycled filament could also be caused by nozzles clogging. The potential presence of microscopic impurities in the filament is the principal problem regarding filament re-extrusion as the process was carried out without a filter.

There was a lack of coherence in the results that illustrated that the recycled average shear strength was roughly 6.8% higher than the virgin equivalent. Possible explanations could be that due to the extruded recycled PET being laid down, changes at the microscopic level occurred when interlocking. Another potential cause is a change in the ratio of the poison which resulted in the sample being compressed against the sides of the shear jig. The risk of increased emissions of ultrafine particles is a disadvantage of using recycled filaments.

4. Discussion

The literature on mechanical property degradation is scarce. Further studies have much to cover, yet would do well to take into account the risks associated with particle emission and inadequate ventilation and act accordingly. Performance enhancement can be boosted by studies that involve recycled and virgin filaments alike [14]. Future studies should also add to and streamline the data on elastic modulus through the use of extensometers. Decreased properties can be attributed to printing problems or filament strength through further testing of filament strands. The mechanical properties of samples fabricated through 3D printing with recycled filaments were the foci of this paper. The results were very encouraging for the field of recycling technology linked to 3D printing as the properties did not vary greatly from the virgin material. Data found in the literature for 3D printed PET and PET reflected the mechanical properties of the virgin material used in this study. While the generated samples were highly usable, slight complications were present when working with the recycled filament. This is the first study that uses a large sample size of around 20 to 32 of both recycled and virgin 3D printed PET, highlighting the shear, the harness, and the tensile of the specimens. This demonstrates that used 3D printer components can be generated that have comparable properties to that of original components.

5. Conclusions

The value of 0.003 was not exceeded by the p-value which, in fact, was substantially lower. A notable variance was present in the printing process using recycled filaments which can be attributed to ineffective filtering in the extrusion process and clogging impurities. This, in turn, led to the increase in variation, principally found in the recycled filament. Comparing the mechanical properties of virgin and 3D printed recycled PET revealed that there is no noteworthy difference in their properties, and this study puts forward novel data on this matter and in the area of 3D recycling. Therefore, this paper supports the reduction of CO2 emissions through the efficient recycling of plastic and environmentally sustainable initiatives. The principal accomplishment and validity of the proposed hypothesis is demonstrated by reaching the 0.003 value. The results bode well for the area of 3D recycling technologies whose evolution and continuous development could lead to recycling 3D printed waste at the local level of small businesses and homes. However, a possible health risk must be considered despite the numerous advantages of this method. These advantages include recycling filaments, reduced use of landfills, and a decrease in carbon dioxide emissions. Through community and small business engagement, costs could be reduced through local recycling and investments around USD 3000 in recycling equipment. Once a hundred pools of filament are generated, a full return on the investment can occur. While mechanical property degradation, increased particle emission, and recycling nozzle clogs, are recycling risks, further studies and initiatives can do much work to mitigate them, such as using high forming temperatures and large nozzles.

The encouraging results seen in this study regarding the recycled PET filament should be reproduced and expanded upon, examining the advantages of filament recycling in tandem with 3D printing and the strengths and feasibility of plastics such as ABS.

Author Contributions

A.O. the main author, wrote the paper, collected the data, and performed the analysis; Z.B. conceived and designed the analysis as well as supervising; L.K. contributed data and analysis tools as well as supervising. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Stipendium Hungaricum and the Hungarian University of Agriculture and life sciences (former Szent Istvan University).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gibson, I.; Rosen, B.; Stucker, B. Additive manufacturing technologies: 3D printing, rapid prototyping, and direct digital manufacturing, 2nd Edition. Johns. Matthey Technol. Rev. 2015, 59, 193–197. [Google Scholar]

- Berman, B. 3D printing: The new industrial revolution. Bus. Horiz. 2012, 55, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, T.; Williams, C.; Ivanova, O.; Garrett, B. Could 3D Printing Change to World? Technologies, Potential, and Implications of Additive Manufacturing; Atlantic Council: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; Strategic Foresight Report; Available online: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/could-3d-printing-change-the-world/ (accessed on 29 December 2018).

- Turner, B.N.; Strong, R.; Gold, S.A. A review of melt extrusion additive manufacturing processes: Process design and modeling. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2014, 20, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Liu, P.; Mokasdar, A. Additive manufacturing and its societal impact: A literature review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2013, 67, 1191–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kira. Wohlers Report 2016 Reveals $1 Billion Growth in 3D Printing Industry. 3D Printing Technology. Wohlers Associates, Inc. 2016. Available online: www.3ders.org/articles/20160405-wohlers-report-2016-reveals-1-billion-growth-in-3d-printing-industry.html (accessed on 2 May 2020).

- Columbus, Louis. 2015 Roundup of 3D Printing Market Forecasts and Estimates Online Blog Posting. Available online: www.forbes.com/sites/louiscolumbus/2015/03/31/2015-roundup-of-3d-printing-market-forecasts-and-estimates/#482faf951dc6 (accessed on 29 December 2020).

- Al-Salem, S.M.; Lettieri, P.; Baeyens, J. Recycling and recovery routes of plastic solid waste (PSW): A review. Waste Manag. 2009, 29, 2625–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Community for Plastics Professionals. Plastic Today. Available online: https://www.plasticstoday.com/packaging/ (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- ASTM D638-14. Standard Test Method for Tensile Properties of Plastics; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2014; Available online: www.astm.org (accessed on 25 March 2020). [CrossRef]

- Rutkowski Joseph, V.; Barbara, C. Levin. Acrylonitrile- Butadiene-Styrene Copolymers (ABS): Pyrolysis and combustion products and their toxicity—A review of the literature. Fire Mater. 1986, 10, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stephens, B.; Azimi, P.; Orch, Z.; Ramos, T. Ultrafine particle emissions from desktop 3D printers. Atmos. Environ. 2013, 79, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, L.; Lobo, H. Cornell University and Datapoint Labs. A Novel Technique to Measure Tensile Properties of Plastics at High Strain Rates. Available online: www.datapointlabs.com/testpaks/antec2005.htm (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- Anderson, I. Mechanical properties of specimens 3D printed with virgin and recycled Polyactic Acid. 3D Print. Addit. Manuf. 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).