Pharmaceuticals in Wastewater Treatment Plants: A Systematic Review on the Substances of Greatest Concern Responsible for the Development of Antimicrobial Resistance

Abstract

:Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Eligibility Criteria and Information Sources

2.2. Search Strategy

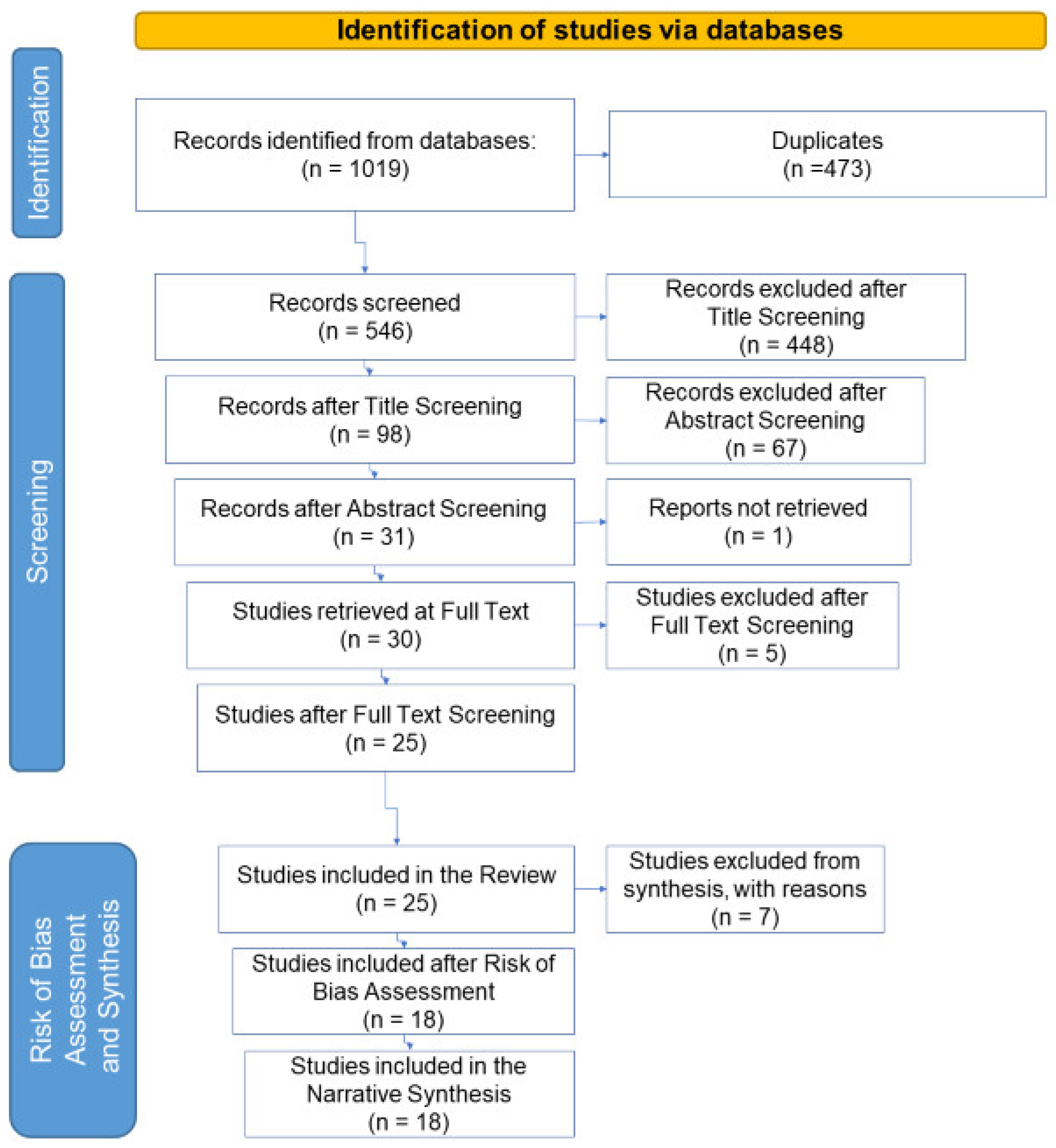

2.3. Selection Process

2.4. Study Risk of Bias Assessment

2.5. Data Collection and Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Study Characteristics

- 17 did not meet the criteria for the key element PRs since dealing with non-pharmaceutical compounds or PRs non-relevant to AMR (Supplementary Material, Data_extraction.xlsx, Sheet PRs List).

- 29 analysed surface water, drinking water or sludge samples and therefore did not satisfy the requirements for WW.

- 256 were off-topic since they investigated specifically resistant organisms or removal treatments.

- 17 were overviews, reviews, global perspectives or insights.

- 2 studies written in Portuguese, a language not included in the list (Table S1).

- 127 were considered not relevant for other reasons not covered in the pre-set criteria: these dealt with metagenomic or metatranscriptomic analyses, bacterial population dynamics, disinfection systems, phages or viruses in WW, bacteria in the aerosol or indicators of pollution.

- 7 focused on one PR only (triclosan, amoxicillin, vancomycin) and therefore did not meet the requirements for the key element PH.

- 5 investigated the PRs concentrations in surface water and not in WW.

- 1 analysed the samples deriving from the WW of a nursing home and not from a municipal or hospital WWTPs.

- 27 did not comply with the criteria defined for the topic, as they investigated resistant bacteria or genes, or new removal treatments in small conditions.

- 13 were reviews or similar.

- 1 was written in Slovenian, a language not included in the list (Table S1).

- 1 was unavailable.

- 13 were excluded based on criteria set during the screening phase (metagenomic or metatranscriptomic, the dynamic of bacterial populations, disinfection systems, phages or virus in WW, bacteria in the aerosol, and indicators of pollutions).

- 2 papers investigated the presence of PRs in WW of pharmaceutical factories, regarded as insignificant since the concentrations and types of antimicrobial substances identified at such plants are not comparable with PRs discharges of hospital or municipal facilities (subject of discussion in this review). Moreover, although pharmaceutical factories are a hotspot for the presence of PRs, usually, antimicrobial substances in their treatment facilities, these are largely and efficiently removed [34].

- 1 study examined sludge and not aqueous WW samples.

- 1 researched antimicrobial substances in biofilms in water environments after WW discharge.

- 1 study developed an analytical method for the quantification of fluoroquinolones antibiotics in WW.

3.2. Risk of Bias in Studies

- 1 did not specify the dates of the sampling campaign. This information is essential to compare studies on seasonal variations of PRs in WW [38].

- 6 showed the PRs concentrations in bar charts only and did not provide tables with single concentration values for each PR and sampling point.

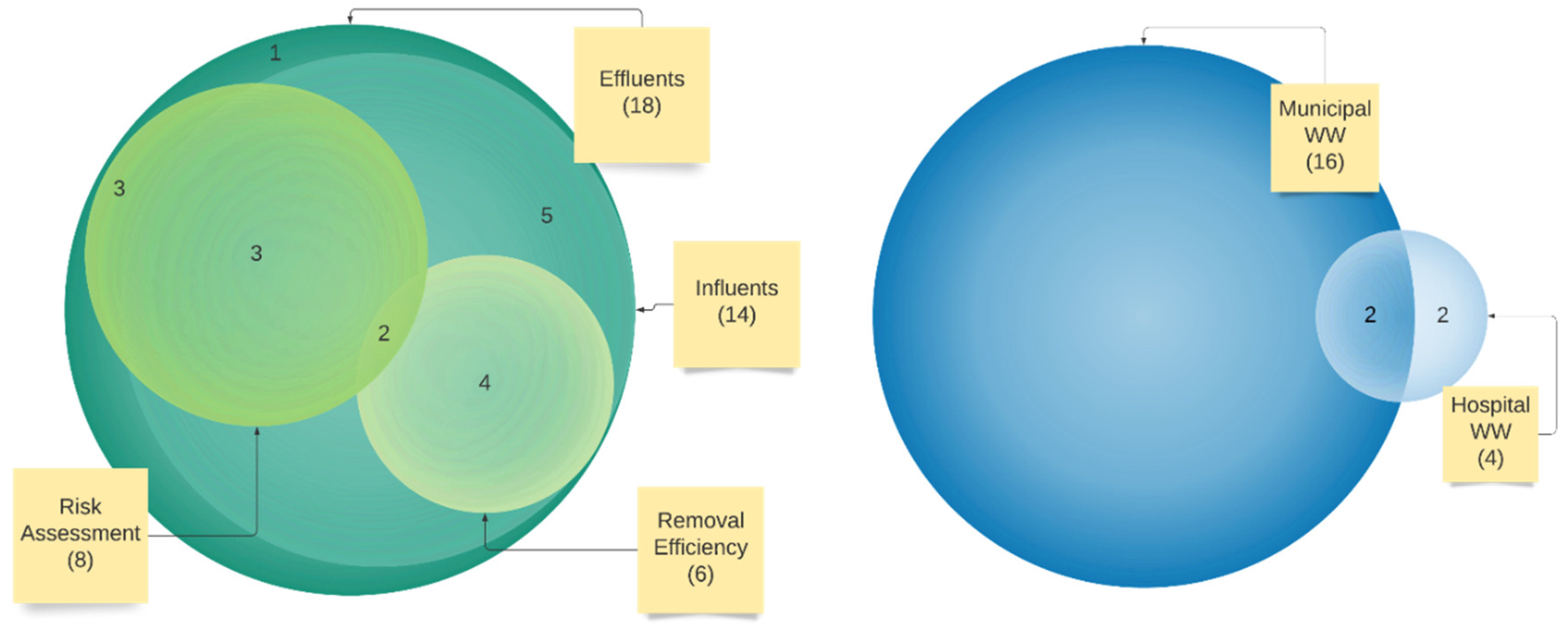

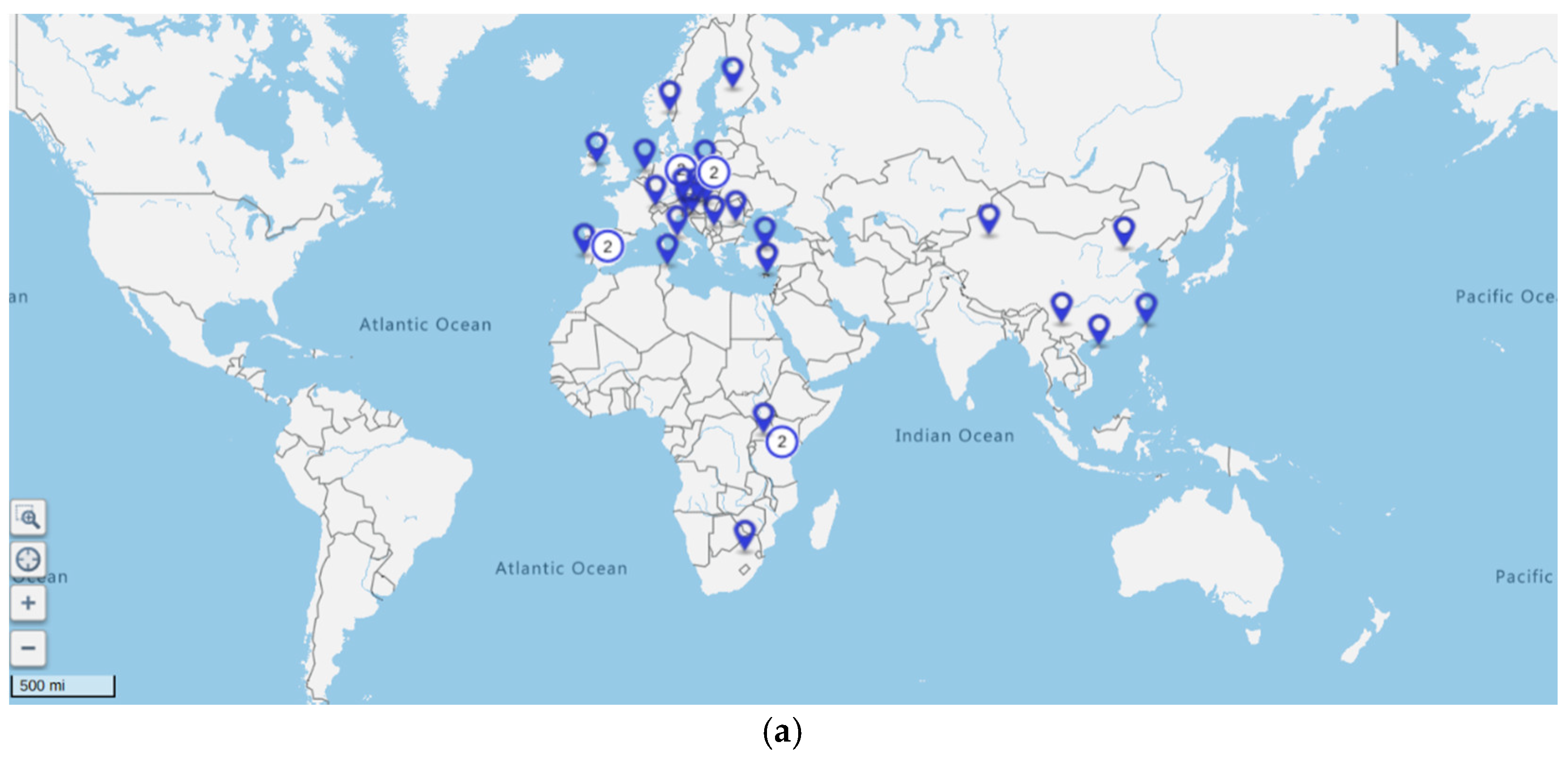

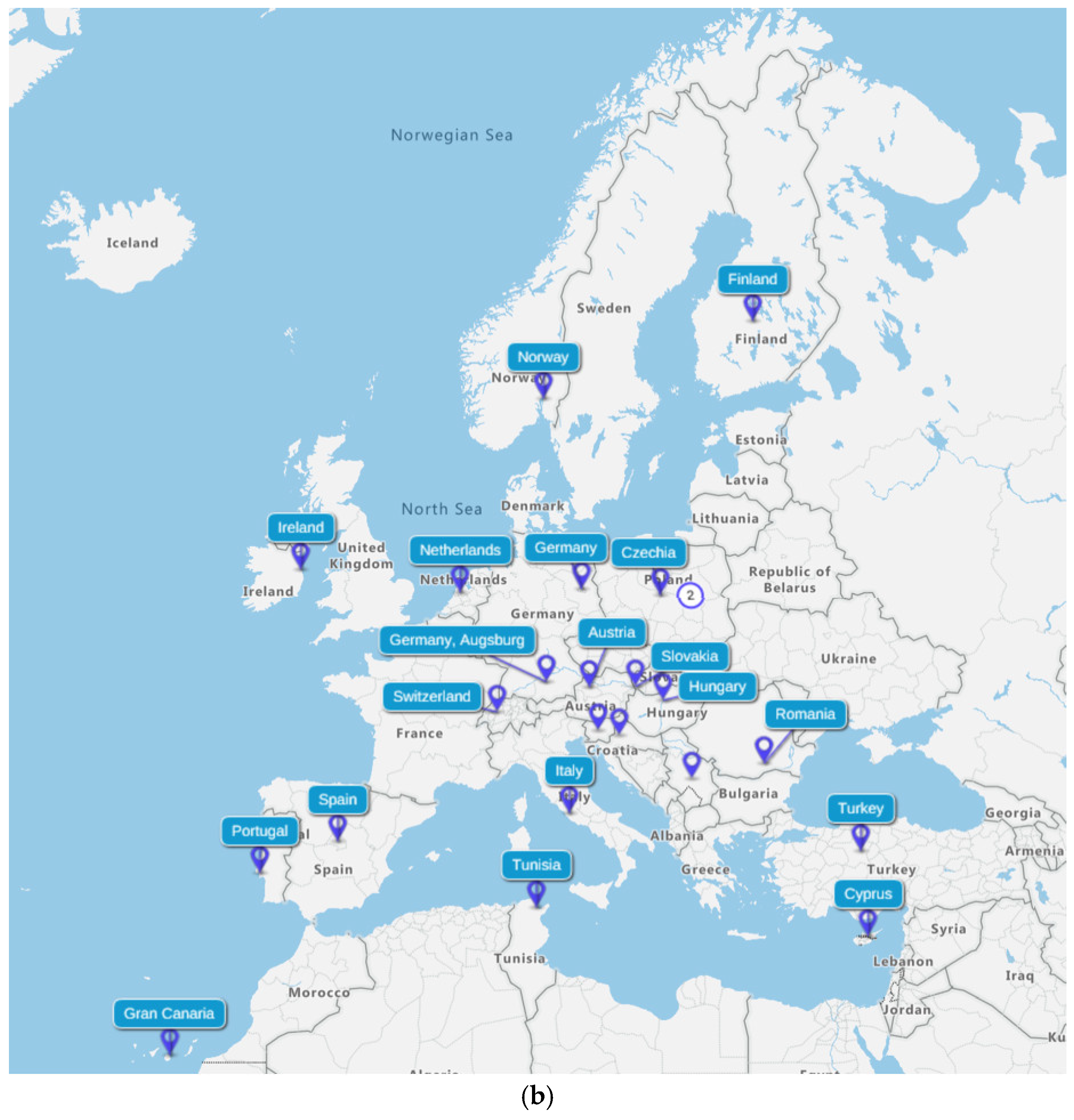

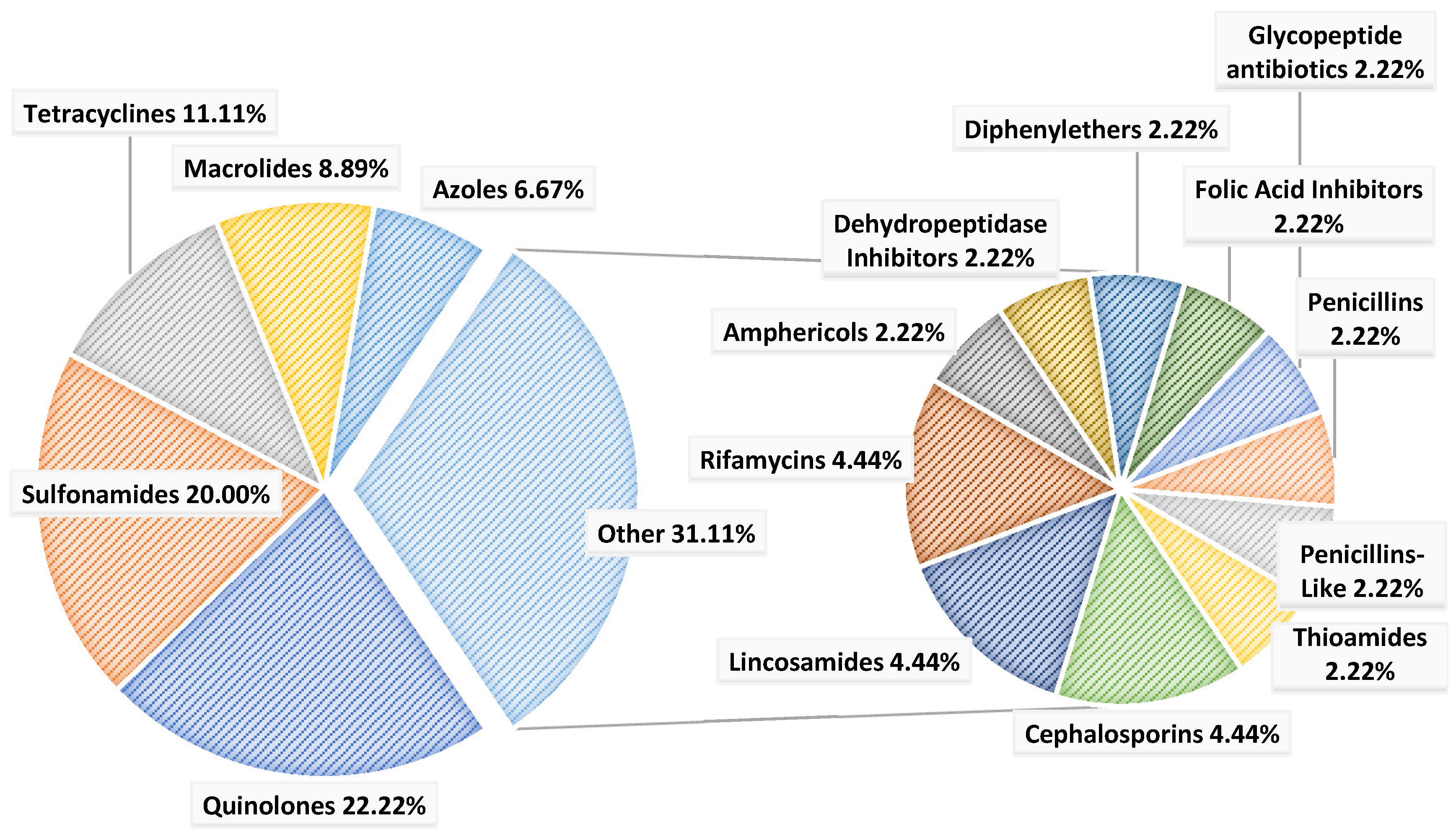

3.3. Characteristics of Studies

4. Discussion

4.1. Concentrations of Pharmaceuticals in Influents and Effluents Wastewater

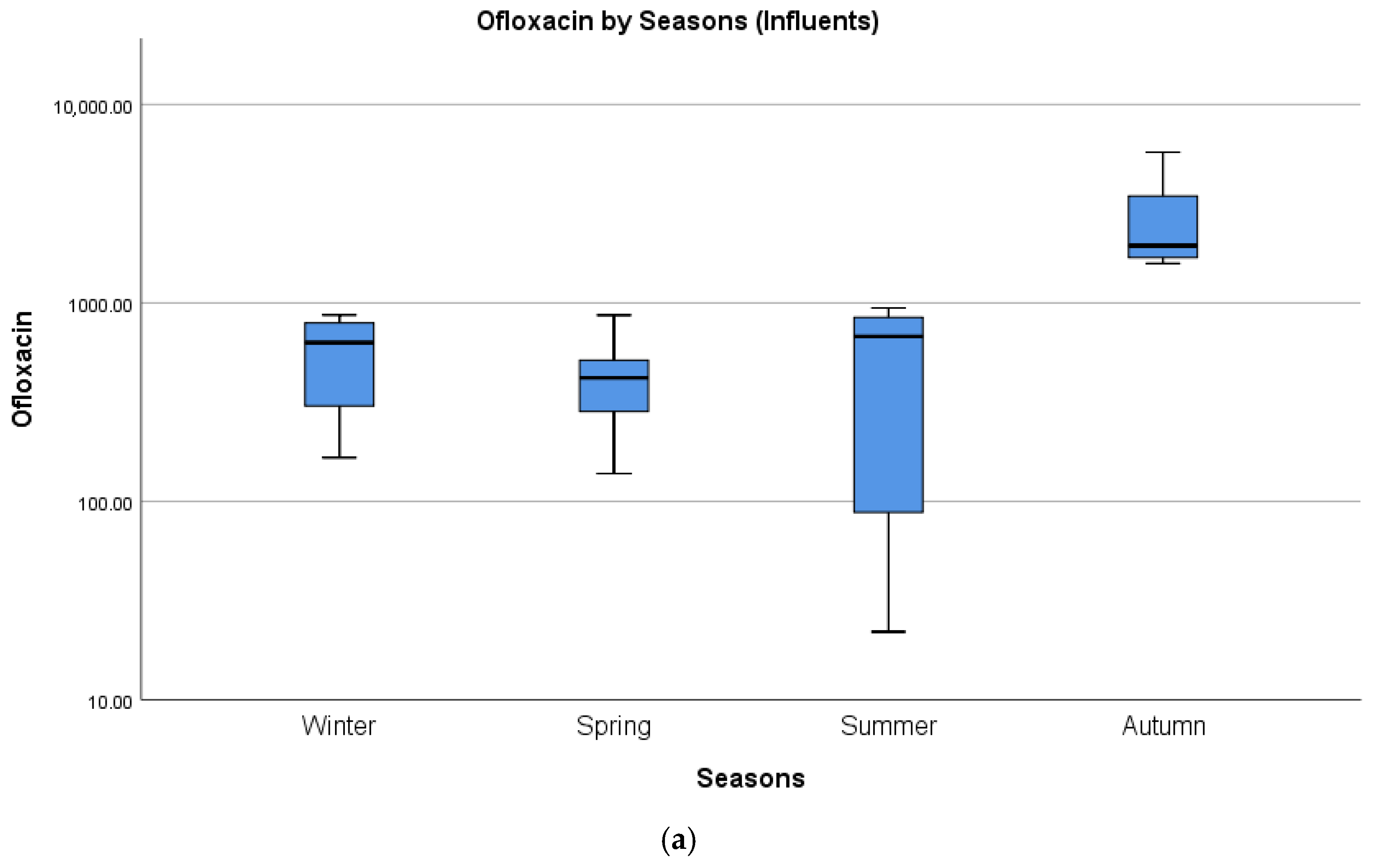

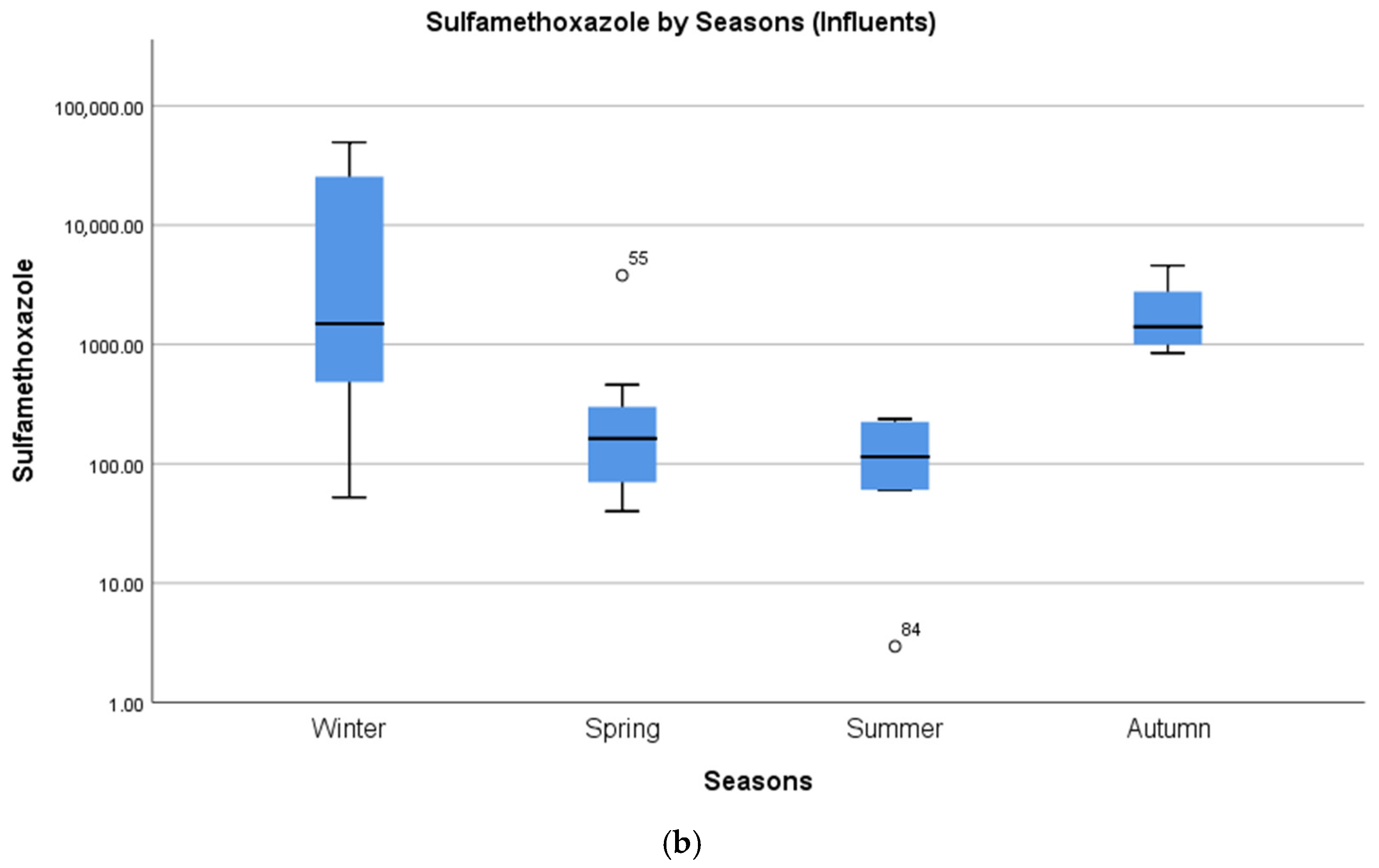

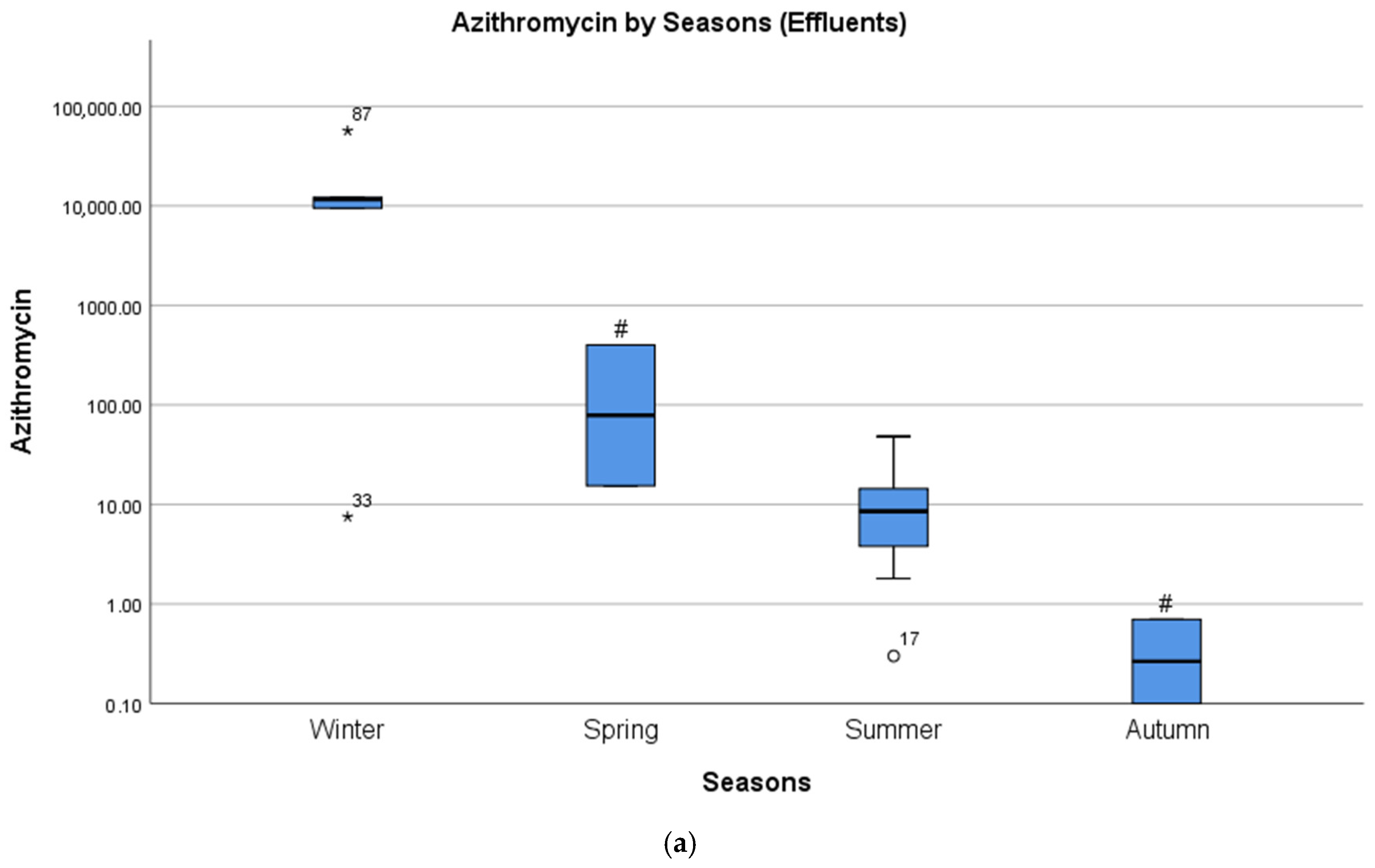

4.2. Seasonal Differences in Concentrations of Pharmaceuticals

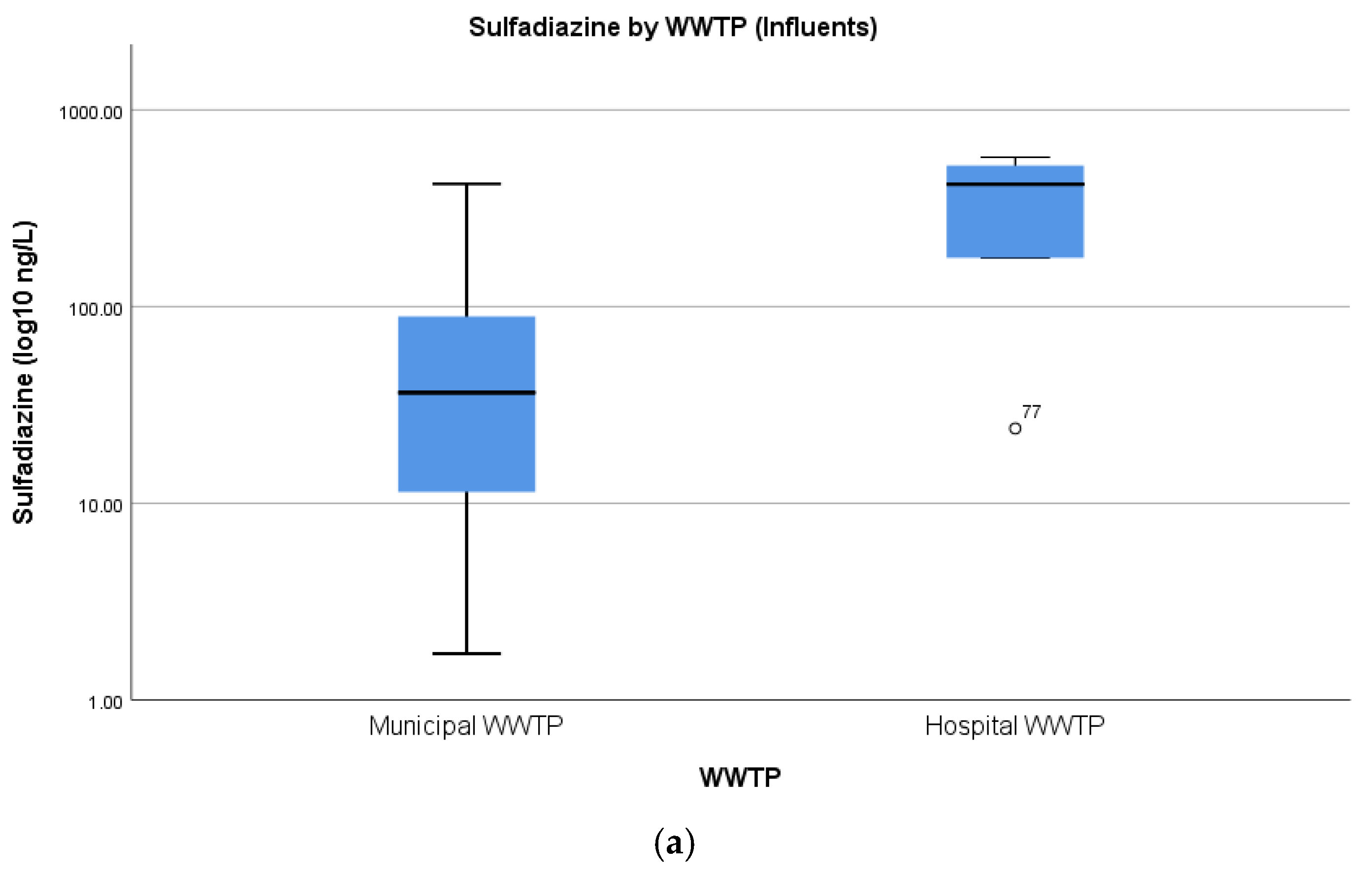

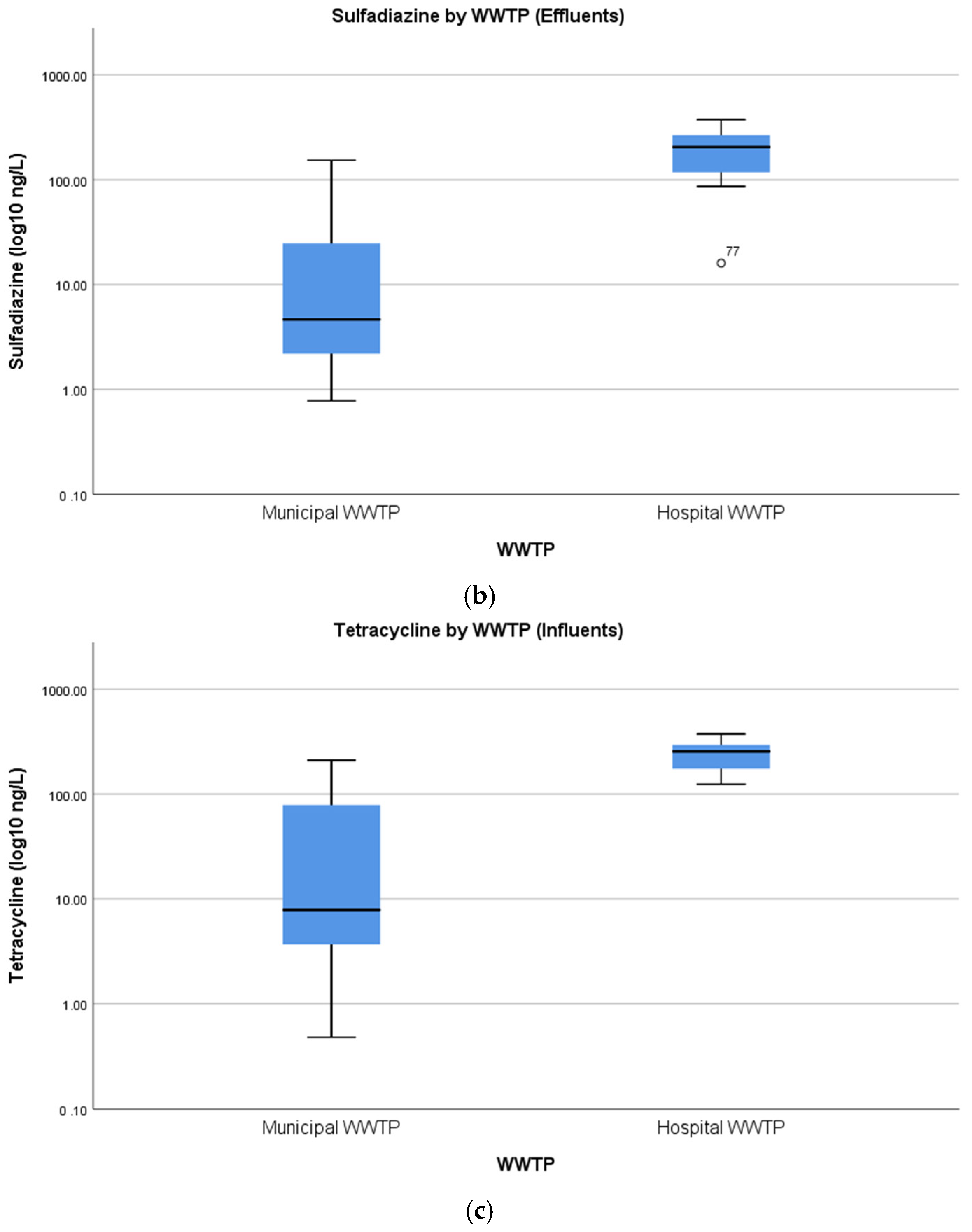

4.3. Concentrations of Pharmaceuticals in Hospital Wastewater

4.4. Environmental Risk Assessment

4.5. Removal Efficiencies of Wastewater Treatment Plants

4.6. Classification of the Pharmaceuticals of Greatest Concern

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

- The reliability of study outcomes must be improved through the implementation of standardised guidelines for the suitable selection of analytical procedures, data representation, and statistical analysis. The experiments should not be based on daily campaigns composing of a singular grab sample, but instead, values for concentrations should be the result of the mean of at least three replicates.

- The need remains for time-weighted screenings to capture seasonal variations in both the influent levels of pharmaceuticals and the effluent levels discharged into aquatic matrices to better assess the impact of wastewater treatment plants on the environment.

- The necessity of studies dealing specifically with the presence of antimicrobial substances in hospital wastewater or correlating the removal efficiencies of wastewater treatment plants with treatments used is stressed.

- Call for awareness about the problem of pharmaceuticals compounds in wastewater and the related spread of antimicrobial resistance: the research in this field needs to be expanded to a global level.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Antimicrobial resistance | AMR |

| European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control | ECDC |

| High-performance liquid chromatography | HPLC |

| Hospital wastewater treatment plants | HWWTPs |

| Hospitals wastewater | HWW |

| Limit of detection | LOD |

| Limit of quantification | LOQ |

| Measured environmental concentration | MEC |

| Method detection limit | MDL |

| Method quantification limit | MQL |

| Minimal inhibitory concentrations | MIC |

| Minimal selective concentration | MSC |

| Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development | OECD |

| Pharmaceutical residues | PRs |

| Predicted environmental concentration | PEC |

| Predicted no-effect concentration | PNEC |

| Risk quotient | RQ |

| Solid-phase extraction | SPE |

| Ultra-performance liquid chromatography | UPLC |

| Wastewater treatment plants | WWTPs |

| Wastewater | WW |

References

- Radjenović, J.; Petrović, M.; Barceló, D. Fate and distribution of pharmaceuticals in wastewater and sewage sludge of the conventional activated sludge (CAS) and advanced membrane bioreactor (MBR) treatment. Water Res. 2009, 43, 831–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gros, M.; Petrović, M.; Ginebreda, A.; Barceló, D. Removal of pharmaceuticals during wastewater treatment and environmental risk assessment using hazard indexes. Environ. Int. 2010, 36, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, P.H.; Thomas, K.V. The occurrence of selected pharmaceuticals in wastewater effluent and surface waters of the lower Tyne catchment. Sci. Total Environ. 2006, 356, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Baig, S.A.; Chen, H.; Cheng, W.; Jiao, Y.; Xu, L. Occurrence and removal of antibiotics and the corresponding resistance genes in wastewater treatment plants: Effluents’ influence to downstream water environment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 6826–6835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, W.; Singer, H.; Berg, M.; Mueller, B.; Pernet-Coudrier, B.; Liu, H.; Qu, J. Elimination of polar micropollutants and anthropogenic markers by wastewater treatment in Beijing, China. Chemosphere 2015, 119, 1054–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dalahmeh, S.; BjöRnberg, E.; Elenström, A.; Komakech, A.J.; Niwagaba, C.B. Pharmaceutical pollution of water resources in Nakivubo wetlands and Lake Victoria, Kampala, Uganda. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 710, 136347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaén-Gil, A.; Hom-Diaz, A.; Llorca, M.; Vicent, T.; Blánquez, P.; Barceló, D.; Rodríguez-Mozaz, S. An automated online turbulent flow liquid-chromatography technology coupled to a high resolution mass spectrometer LTQ-Orbitrap for suspect screening of antibiotic transformation products during microalgae wastewater treatment. J. Chromatogr. A 2018, 1568, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, H.O.A.; Voulvoulis, N.; Lester, J.N. Human pharmaceuticals in wastewater treatment processes. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 35, 401–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lu, J.; Engelstädter, J.; Zhang, S.; Ding, P.; Mao, L.; Yuan, Z.; Bond, P.L.; Guo, J. Non-antibiotic pharmaceuticals enhance the transmission of exogenous antibiotic resistance genes through bacterial transformation. ISME J. 2020, 14, 2179–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Mozaz, S.; Vaz-Moreira, I.; Varela Della Giustina, S.; Llorca, M.; Barceló, D.; Schubert, S.; Berendonk, T.U.; Michael-Kordatou, I.; Fatta-Kassinos, D.; Martinez, J.L.; et al. Antibiotic residues in final effluents of European wastewater treatment plants and their impact on the aquatic environment. Environ. Int. 2020, 140, 105733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, G.; Kaya, Y.; Vergili, I.; Beril Gönder, Z.; Özhan, G.; Ozbek Celik, B.; Altinkum, S.M.; Bagdatli, Y.; Boergers, A.; Tuerk, J. Characterisation and toxicity of hospital wastewaters in Turkey. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2017, 189, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alygizakis, N.A.; Besselink, H.; Paulus, G.K.; Oswald, P.; Hornstra, L.M.; Oswaldova, M.; Medema, G.; Thomaidis, N.S.; Behnisch, P.A.; Slobodnik, J. Characterisation of wastewater effluents in the Danube River Basin with chemical screening, in vitro bioassays and antibiotic resistant genes analysis. Environ. Int. 2019, 127, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giebułtowicz, J.; Nałęcz-Jawecki, G.; Harnisz, M.; Kucharski, D.; Korzeniewska, E.; Płaza, G. Environmental Risk and Risk of Resistance Selection Due to Antimicrobials’ Occurrence in Two Polish Wastewater Treatment Plants and Receiving Surface Water. Molecules 2020, 25, 1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Castiglioni, S.; Zuccato, E.; Fattore, E.; Riva, F.; Terzaghi, E.; Koenig, R.; Principi, P.; Di Guardo, A. Micropollutants in Lake Como water in the context of circular economy: A snapshot of water cycle contamination in a changing pollution scenario. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 384, 141441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kairigo, P.; Gachanja, A.; Ngumba, E.; Sundberg, L.; Tuhkanen, T. Occurrence of antibiotics and risk of antibiotic resistance evolution in selected Kenyan wastewaters, surface waters and sediments. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 720, 137580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimosop, S.J.; Getenga, Z.M.; Orata, F.; Okello, V.A.; Cheruiyot, J.K. Residue levels and discharge loads of antibiotics in wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), hospital lagoons, and rivers within Lake Victoria Basin, Kenya. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2016, 188, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, B.; Geng, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, P. Emission and ecological risk of pharmaceuticals and personal care products affected by tourism in Sanya City, China. Environ. Geochem. Health 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. The 2019 WHO AWaRe Classification of Antibiotics for Evaluation and Monitoring of Use; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://www.who.int/medicines/news/2019/WHO_releases2019AWaRe_classification_antibiotics/en/ (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- CDC. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States; US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2019. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/threats-report/2019-ar-threats-report-508.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- CDC. Antifungal Resistance. Atalanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/antifungal-resistance.html#what-causes (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- NHS. Antifungal Medicines; National Health System: London, UK, 2020; Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/antifungal-medicines/ (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- Yadav, S.; Jadeja, N.B.; Dafale, N.D.; Purohit, H.; Kapley, A. 17-Pharmaceuticals and personal care products mediated antimicrobial resistance: Future challenges. In Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products: Waste Management and Treatment Technology; Prasad, M.N.V., Vithanage, M., Kapley, A., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 409–428. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, E.D.; Wright, G.D. Antibacterial drug discovery in the resistance era. Nature 2016, 529, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. EU Health Ministerial Meeting—Next Steps towards Making the EU a Best Practice Region in Combating AMR. Bucharest, Romania. 2019. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/health/health-systems/AMR-Tackling-the-Burden-in-the-EU-OECD-ECDC-Briefing-Note-2019.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- Directive 2008/105/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2008/105/oj (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- Carvalho, R.; Ceriani, L.; Ippolito, A.; Lettieri, T. Development of the First Watch List under the Environmental Quality Standards Directive, 2015. Report EUR 27142. Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/bitstream/JRC95018/lbna27142enn.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- Leimu, R.; Koricheva, J. What determines the citation frequency of ecological papers? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2005, 20, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayliss, H.R.; Beyer, F.R. Information retrieval for ecological syntheses. Res. Synth. Methods 2015, 6, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Parekh, S.; Hooper, L.; Loke, Y.K.; Ryder, J.; Sutton, A.J.; Hing, C.; Kwok, C.S.; Pang, C.; Harvey, I. Dissemination and publication of research findings: An updated review of related biases. Health Technol. Assess. 2010, 14, 1–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickersin, K. Publication Bias: Recognising the Problem, Understanding Its Origins and Scope, and Preventing Harm. Chapter 2. In Publication Bias in Meta-Analysis: Prevention, Assessment and Adjustments; Rothstein, H.R., Sutton, A.J., Borenstein, M., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 9–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahimi, S.M.; Dehghanzadeh Reyhani, R.; Asghari-Jafarabadi, M.; Fathifar, Z. Diversity of antibiotics in hospital and municipal wastewaters and receiving water bodies and removal efficiency by treatment processes: A systematic review protocol. Environ. Evid. 2020, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2020, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Jüni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savović, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A.C. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, L.; Guo, C.; Fan, S.; Lv, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Xu, J. Dynamic transport of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes under different treatment processes in a typical pharmaceutical wastewater treatment plant. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 30191–30198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, G.K.; Hornstra, L.M.; Alygizakis, N.; Slobodnik, J.; Thomaidis, N.; Medema, G. The impact of on-site hospital wastewater treatment on the downstream communal wastewater system in terms of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2019, 222, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moslah, B.; Hapeshi, E.; Jrad, A.; Fatta-Kassinos, D.; Hedhili, A. Pharmaceuticals and illicit drugs in wastewater samples in north-eastern Tunisia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 18226–18241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afonso-Olivares, C.; Sosa-Ferrera, Z.; Santana-Rodriguez, J.J. Occurrence and environmental impact of pharmaceutical residues from conventional and natural wastewater treatment plants in Gran Canaria (Spain). Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 599, 934–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlicchi, P.; Al Aukidy, M.; Zambello, E. Occurrence of pharmaceutical compounds in urban wastewater: Removal, mass load and environmental risk after a secondary treatment—A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 429, 123–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faleye, A.C.; Adegoke, A.A.; Ramluckan, K.; Fick, J.; Bux, F.; Stenström, T.A. Concentration and reduction of antibiotic residues in selected wastewater treatment plants and receiving waterbodies in Durban, South Africa. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 678, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.R.; Angeles, L.F.; Butryn, D.M.; Metch, J.W.; Garner, E.; Vikesland, P.J.; Aga, D.S. Towards a harmonised method for the global reconnaissance of multi-class antimicrobials and other pharmaceuticals in wastewater and receiving surface waters. Environ. Int. 2019, 124, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barancheshme, F.; Munir, M. Strategies to combat antibiotic resistance in the wastewater treatment plants. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scott, G.; Porter, D.; Norman, R.; Scott, C.; Uyaguari-Diaz, M.; Maruya, K.; Weisberg, S.; Fulton, M.; Wirth, E.; Moore, J.; et al. Antibiotics as CECs: An Overview of the Hazards Posed by Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance. Front. Mar. Sci. 2016, 3, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wallace, J.; Youngblood, J.; Port, J.; Cullen, A.; Smith, M.; Workman, T.; Faustman, E. Variability in metagenomic samples from the Puget Sound: Relationship to temporal and anthropogenic impacts. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, M.; Pruden, A.; Chen, C.; Heath, L.; Xia, K.; Zhang, L. MetaCompare: A computational pipeline for prioritising environmental resistome risk. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2018, 94, fiy079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paiva, M.C.; Reis, M.P.; Costa, P.S.; Dias, M.F.; Bleicher, L.; Scholte, L.L.S.; Nardi, R.M.D.; Nascimento, A. Identification of new bacteria harboring qnrS and aac (6′)-Ib/cr and mutations possibly involved in fluoroquinolone resistance in raw sewage and activated sludge samples from a full-scale WWTP. Water Res. 2017, 110, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conte, D.; Palmeiro, J.K.; Nogueira, K.D.S.; Lima, R.; Marenda, T.; Cardoso, M.A.; Pontarolo, R.; Degaut Pontes, F.L.; Dalla-Costa, L.M. Characterisation of CTX-M enzymes, quinolone resistance determinants, and antimicrobial residues from hospital sewage, wastewater treatment plant, and river water. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2017, 136, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santoro, D.O.; Cardoso, A.M.; Coutinho, F.H.; Pinto, L.H.; Vieira, R.P.; Albano, R.M.; Clementino, M.M. Diversity and antibiotic resistance profiles of Pseudomonads from a hospital wastewater treatment plant. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2015, 119, 1527–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Lu, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, G.; Tong, Y.; Ma, N. Exploring the correlations between antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in the wastewater treatment plants of hospitals in Xinjiang, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 15111–15121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Zeng, S.; Dong, X.; Li, D.; Zhang, Y.; He, M.; Du, P. Diverse and abundant antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in an urban water system. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 231, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kot-Wasik, A.; Jakimska, A.; Śliwka-Kaszyńska, M. Occurrence and seasonal variations of 25 pharmaceutical residues in wastewater and drinking water treatment plants. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2016, 188, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson-Palme, J.; Larsson, D.G.J. Concentrations of antibiotics predicted to select for resistant bacteria: Proposed limits for environmental regulation. Environ. Int. 2016, 86, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khan, S.; Beattie, T.K.; Knapp, C.W. The use of minimum selectable concentrations (MSCs) for determining the selection of antimicrobial resistant bacteria. Ecotoxicology 2017, 26, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, Y.; Shen, W.; Wang, B.; Zhao, X.; Su, L.; Kong, M.; Li, H.; Zhang, S.; Li, J. Occurrence and fate of antibiotics, antimicrobial resistance determinants and potential human pathogens in a wastewater treatment plant and their effects on receiving waters in Nanjing, China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 206, 111371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topal, M.; Topal, E.I.A. Occurrence and fate of tetracycline and degradation products in municipal biological wastewater treatment plant and transport of them in surface water. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2015, 187, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, K. Occurrence of a Wide Range of Antibiotics, Estrogenic Hormones, and UV-Filters in Engineered and Natural Systems: Development of Analytical Methods and Investigation of Ecological Effects. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fries, E.; Mahjoub, O.; Mahjoub, B.; Berrehouc, A.; Lions, J.; Bahadir, M. Occurrence of contaminants of emerging concern (CEC) in conventional and nonconventional water resources in Tunisia. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2016, 25, 3317–3339. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Lam, J.C.W.; Li, W.; Yu, H.; Lam, P.K.S. Spatial distribution and removal performance of pharmaceuticals in municipal wastewater treatment plants in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 586, 1162–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Meng, J.; Zhang, M.; Chen, S.; He, B.; Zhao, H.; Li, Q.; Zhang, S.; Wang, T. Which type of pollutants need to be controlled with priority in wastewater treatment plants: Traditional or emerging pollutants? Environ. Int. 2019, 131, 104982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbhuiya, N.H.; Adak, A. Determination of antimicrobial concentration and associated risk in water sources in West Bengal state of India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bias | Study | Bias | Bias |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domain | Parameter | Assessment | Score |

| Selection Bias | PRs sampling | Authors attempted to analyse all the PRs in WW samples (wide-scope screenings preceded the detection and quantification of examined PRs) | Yes = 2, No = 0, Unclear = 1 |

| If not, the number of PRs analysed was less or more than 10 | ≤10 = 0, ≥10 = 1, ≥50 = 2 | ||

| Authors explained reasons for their selection of PRs, WW, WWTPs | Yes = 2, No = 0, Unclear = 1 | ||

| PRs detection | Period of sampling campaigns | ≤1 week = 0, ≥1 week = 1, | |

| ≥1 year = 2 | |||

| Composite samples | Yes = 2, No = 0, Unclear = 1 | ||

| Volume analysed during the detection phase | ≤50 mL = 0, >50 mL = 1, | ||

| ≥250 mL = 2 | |||

| Performance Bias | Sampling and analytical techniques | Samples stored on ice and in dark conditions | Yes = 2, No = 0, Unclear = 1 |

| Samples stored for less or more than 24 h before the analytical phase | ≤24 h = 2, >24 h/unclear = 1, ≥72 h = 0 | ||

| Description and correct preparation and preservation of reagents and solutions | Yes = 2, No = 0, Unclear = 1 | ||

| Detection Bias | Sample pre-treatment | Solid-phase extraction (SPE) during the extraction phase | Yes = 2, No = 0, Unclear = 1 |

| PRs detection technique | Gas or Liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry | Yes = 2, No = 0, Unclear = 1 | |

| Sampling and detection technique | Validation of the analytical method (MDL or LOD, MQL or LOQ *, recovery) | Yes = 2, No = 0, Unclear = 1 | |

| Attrition Bias | Data analysis | Missing data | Yes = 0, No = 2, Unclear = 1 |

| If so, the authors explained with appropriate reasons the lack of data | Yes = 2, No = 1, Unclear = 1 | ||

| Reporting Bias | Data presentation | Presentation and description of Statistical Analyses | Yes = 2, No = 0, Unclear = 1 |

| Authors reported only statistically significant data | Yes = 0, No = 2, Unclear = 1 | ||

| Standard Deviation values represented | Yes = 2, No = 0, Unclear = 1 | ||

| Authors selectively reported only a part of the results | Yes = 0, No = 2, Unclear = 1 | ||

| Risk assessment of PRs (Risk quotient: RQ) | Yes = 2, No = 0, Unclear = 1 | ||

| Other Bias | Sponsor | Status of funding | Clear = 2, Unclear = 1 |

| Database | No. of References after 2015 | No. of References before 2015 |

|---|---|---|

| (Percentage) | (Percentage), Year of the First Publication | |

| Web of Science | 170 (68.0%) | 80 (32.0%), 2000 |

| PubMed/Medline | 195 (62.3%) | 118 (37.7%), 2001 |

| ProQuest 1st search | 2544 (66.5%) | 1280 (33.5%), 1992 |

| ProQuest 2st search | 618 (68.4%) | 286 (31.6%), 1992 |

| BASE | 36 (66.7%) | 18 (33.3%), 2009 |

| Total | 1019 (mean 67.0%) | 502 (mean 33.0%) |

| Study | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| Score | 67.5 | 45 | 77.5 | 62.5 | 60 | 70 | 65 | 65 | 75 | 65 | 55 | 65 | 62.5 |

| Study | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | |

| Score | 70 | 55 | 52.5 | 60 | 70 | 45 | 45 | 77.5 | 65 | 80 | 70 | 52.5 |

| Pharmaceutical | Max. Average Conc. (ng/L) Detected in Influents | City (Country) | Ref. | Mean across Studies (ng/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azithromycin | 115,413 | Sanya City (China) | [17] | 12,856 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 88,012 | Durban (South Africa) | [39] | 8706 |

| Clarithromycin | 6917 | Sanya City (China) | [17] | 732 |

| Clindamycin | 134 | Warsaw (Poland) | [13] | 53 |

| Erythromycin | 1193 | Choutrana (Tunisia) | [36] | 295 |

| Metronidazole | 20,656 | Durban (South Africa) | [39] | 2002 |

| Norfloxacin | 2800 | Kangemi (Kenya) | [15] | 454 |

| Ofloxacin | 5742 | Durban (South Africa) | [39] | 764 |

| Oxytetracycline | 1531 | Sanya City (China) | [17] | 241 |

| Roxithromycin | 19,135 | Sanya City (China) | [17] | 2045 |

| Sulfadiazine | 574 | Xinjiang (China) | [48], H | 179 |

| Sulfamethoxazole | 49,300 | Machakos (Kenya) | [15] | 4434 |

| Tetracycline | 374 | Xinjiang (China) | [48], H | 115 |

| Trimethoprim | 8430 | Kampala (Uganda) | [6] | 982 |

| Class | Pharmaceutical | No. of Studies in Which the PR Was Detected (% of the Total) | Max. Average Conc. (ng/L) Detected in Effluents | Min. Average Conc. (ng/L) Detected in Effluents * | Mean across Studies (ng/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amphericols | Chloramphenicol | 3 (16.7) | 97 [12] | 5.9 [50] | 50 |

| Azoles | Fluconazole | 3 (16.7) | 170 [5] | 3 [35], H | 73 |

| Metronidazole | 10 (55.6) | 3000 [11], H | 1.2 [39] | 330 | |

| Tinidazole | 1 (5.6) | 12 [49] | 9.1 [49] | 10 | |

| Cephalosporins | Cefalexin | 2 (11.1) | 308 [10] | 5.0 [35] | 117 |

| Ceftazidime | 1 (5.6) | 1600 [11], H | 1600 [11], H | 1600 | |

| Dehydropeptidase Inhibitors | Cilastatin | 1 (5.6) | 4100 [11] | 4100 [11], H | 4100 |

| Diphenylethers | Triclosan | 1 (5.6) | 7.4 [12] | 0.9 [12] | 4.2 |

| Folic Acid Inhibitors | Trimethoprim | 14 (77.8) | 26,100 [6] | 1.6 [17] | 1979 |

| Glycopeptide antibiotics | Vancomycin | 2 (11.1) | 162 [13] | 81 [14] | 119 |

| Lincosamides | Clindamycin | 5 (27.8) | 290 [13] | 0.5 [39] | 71 |

| Lincomycin | 4 (22.2) | 56 [13] | 1.5 [12] | 26 | |

| Macrolides | Azithromycin | 8 (44.4) | 56,666 [17] | 0.1 [39] | 4387 |

| Clarithromycin | 12 (66.7) | 15,000 [11], H | 0.2 [39] | 750 | |

| Erythromycin | 11 (61.1) | 1187 [36] | 0.1 [39] | 304 | |

| Roxithromycin | 6 (33.3) | 6272 [17] | 3.6 [17] | 882 | |

| Penicillins | Ampicillin | 4 (22.2) | 790 [16], H | 60 [16] | 254 |

| Penicillins-Like | Amoxicillin | 4 (22.2) | 1600 [15] | 40 [12] | 463 |

| Quinolones | Ciprofloxacin | 15 (83.3) | 24,000 [11], H | 0.6 [17] | 1137 |

| Flumequine | 3 (16.7) | 63 [12] | 3.0 [35], H | 28 | |

| Lomefloxacin | 2 (11.1) | 4.6 [17] | 0.3 [17] | 1.6 | |

| Marbofloxacin | 1 (5.6) | <LOD [35] | <LOD [35] | <LOD | |

| Nalidixic Acid | 2 (11.1) | 50 [10] | 7.8 [49] | 24 | |

| Norfloxacin | 8 (44.4) | 2900 [15] | 0.5 [39] | 221 | |

| Ofloxacin | 12 (66.7) | 200,000 [11], H ** | 2.7 [17] | 7405 | |

| Oxolinic Acid | 3 (16.7) | 60 [12] | 4.6 [12] | 19 | |

| Sparfloxacin | 1 (5.6) | <LOD [6] | <LOD [6] | <LOD | |

| Sulfamerazine | 1 (5.6) | 28 [17] | 0.3 [17] | 8.0 | |

| Rifamycins | Rifampicin | 1 (5.6) | 2.9 [13] | 2.9 [13] | 2.9 |

| Rifaximin | 2 (11.1) | 12 [12] | 3.8 [12] | 7.0 | |

| Sulfonamides | Sulfadiazine | 8 (44.4) | 373 [48], H | 0.8 [17] | 53 |

| Sulfadimidine | 2 (11.1) | 106 [12] | 3 [12] | 54 | |

| Sulfadoxine | 1 (5.6) | <LOD [35] | <LOD [35] | <LOD | |

| Sulfamethazine | 4 (22.2) | 21 [17] | 0.8 [17] | 7.0 | |

| Sulfamethizole | 2 (11.1) | 19 [17] | 0.04 [23] | 3.6 | |

| Sulfamethoxazole | 16 (88.9) | 21,400 [15] | 1.0 [35], H | 1217 | |

| Sulfamoxole | 1 (5.6) | <LOD [35] | <LOD [35] | <LOD | |

| Sulfathiazole | 1 (5.6) | 138 [17] | 0.9 [17] | 21 | |

| Sulfisoxazole | 1 (5.6) | 20 [17] | 1.6 [17] | 8.1 | |

| Tetracyclines | Chlortetracycline | 2 (11.1) | 12 [48], H | 0.5 [17] | 4.0 |

| Doxycycline | 3 (16.7) | 1500 [15] | 0.4 [17] | 191 | |

| Minocycline | 1 (5.6) | 210 [12] | 21 [12] | 116 | |

| Oxytetracycline | 5 (27.8) | 416 [17] | 0.1 [13] | 65 | |

| Tetracycline | 6 (33.3) | 231 [10] | 0.6 [17] | 41 | |

| Thioamides | Ethionamide | 1 (5.6) | 9.3 [39] | 0.2 [39] | 4.8 |

| Pharmaceutical | No. of Studies in Which the PRs Exceeded the High-Risk Level (% of the Total) | Risk Quotient (RQ) a for PRs in Effluent WW (Countries) | Highest Detected Average Conc. in WWTPs Effluents (ng/L) | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amoxicillin | 1 (12.5) | 6.4 (Kenya) | 1600 | [15] |

| Azithromycin | 3 (37.5) | 0.02–377.8 (China) | 56,666 | [17] |

| 3.6–56.9 * (Cyprus, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Portugal, Spain) | 598 | [10] | ||

| 1.3–34.2 (Poland) | 650 | [13] | ||

| Cefalexin | 1 (12.5) | 1.2–17.0 * (Cyprus, Ireland, Portugal, Spain, Finland) | 308 | [10] |

| Ciprofloxacin | 3 (37.5) | 40.6 (Kenya) | 2600 | [15] |

| 24.212 a (Spain) | 89 | [37] | ||

| 1.6–19.6 * (Cyprus, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Portugal, Spain) | 589 | [10] | ||

| Clarithromycin | 3 (37.5) | 16.7 (Switzerland) | 234 | [14] |

| 1.9–4.0 (Poland) | 160 | [13] | ||

| 1.8–4.6 * (Germany, Ireland, Portugal, Spain) | 313 | [10] | ||

| Ofloxacin | 2 (14.29) | 2.6 (Danube river basin) b | 3051 | [12] |

| 0.02–1.3 (China) | 180 | [17] | ||

| Norfloxacin | 1 (12.5) | 5.8 (Kenya) | 2900 | [15] |

| Roxithromycin | 1 (12.5) | 0.1–98.2 (China) | 6272 | [17] |

| Sulfathiazole | 1 (12.5) | 0–3.2 (China) | 134 | [17] |

| Sulfamethoxazole | 3 (37.5) | 12.7 (Spain) | 977 | [37] |

| 3.5 (Kenya) | 21,400 | [15] | ||

| 1.1–1.3 (Poland) | 770 | [13] | ||

| Trimethoprim | 1 (12.5) | 1.0 (Kenya) | 500 | [15] |

| Pharmaceutical | No. of Studies in Which the PRs Occur (% of the Total) | Max Removal Efficiency (%) | Min Removal Efficiency (%) | Average Removal Efficiency among the Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erythromycin | 5 (83.3) | 99.9 [37] | −193.0 [39] | 10.3 |

| Sulfamethoxazole | 5 (83.3) | 100.0 [39] | −504.2 [37] | 22.2 |

| Metronidazole | 3 (50.0) | 99.9 [37] | −320.0 [5] | 28.5 |

| Trimethoprim | 5 (83.3) | 99.9 [37] | −23.0 [17] | 54.0 |

| Clarithromycin | 4 (66.7) | 100.0 [36,39] | −22.0 [5] | 68.1 |

| Ofloxacin | 5 (83.3) | 100.0 [39] | 7.0 [36] | 79.9 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 4 (66.7) | 100.0 [36,39] | 44.5 [17] | 88.4 |

| Bengtsson-Palme and Larsson Study | This Study | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceutical | No. of Different Species with Reported MIC | Size-Adjusted Lowest MIC a (ng/L) | PNEC b Resistance Selection (ng/L) | % > MIC c (No. of Studies) [Ref.] | % > PNEC d (No. of Studies) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 70 | 1000 | 64 | 16.67 (2), [2,16] | 75.0 (9) |

| Clarithromycin | 15 | 2000 | 250 | 9.09 (1), [11] | 45.5 (5) |

| Ofloxacin | 26 | 4000 | 500 | 9.09 (1), [11] * | 45.5 (5) |

| Trimethoprim | 22 | 8000 | 500 | 7.69 (1), [6] | 30.8 (4) |

| Metronidazole | 6 | 2000 | 125 | 12.50 (1), [11] | 25.0 (2) |

| Erythromycin | 39 | 8000 | 1000 | 0.00 (0) | 22.2 (2) |

| Sulfamethoxazole | 8 | 125,000 | 16,000 | 0.00 (0) | 6.7 (1) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Frascaroli, G.; Reid, D.; Hunter, C.; Roberts, J.; Helwig, K.; Spencer, J.; Escudero, A. Pharmaceuticals in Wastewater Treatment Plants: A Systematic Review on the Substances of Greatest Concern Responsible for the Development of Antimicrobial Resistance. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6670. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11156670

Frascaroli G, Reid D, Hunter C, Roberts J, Helwig K, Spencer J, Escudero A. Pharmaceuticals in Wastewater Treatment Plants: A Systematic Review on the Substances of Greatest Concern Responsible for the Development of Antimicrobial Resistance. Applied Sciences. 2021; 11(15):6670. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11156670

Chicago/Turabian StyleFrascaroli, Gabriele, Deborah Reid, Colin Hunter, Joanne Roberts, Karin Helwig, Janice Spencer, and Ania Escudero. 2021. "Pharmaceuticals in Wastewater Treatment Plants: A Systematic Review on the Substances of Greatest Concern Responsible for the Development of Antimicrobial Resistance" Applied Sciences 11, no. 15: 6670. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11156670

APA StyleFrascaroli, G., Reid, D., Hunter, C., Roberts, J., Helwig, K., Spencer, J., & Escudero, A. (2021). Pharmaceuticals in Wastewater Treatment Plants: A Systematic Review on the Substances of Greatest Concern Responsible for the Development of Antimicrobial Resistance. Applied Sciences, 11(15), 6670. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11156670