Efficacy of an Acupressure Mat in Association with Therapeutic Exercise in the Management of Chronic Low Back Pain: A Prospective Randomized Controlled Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

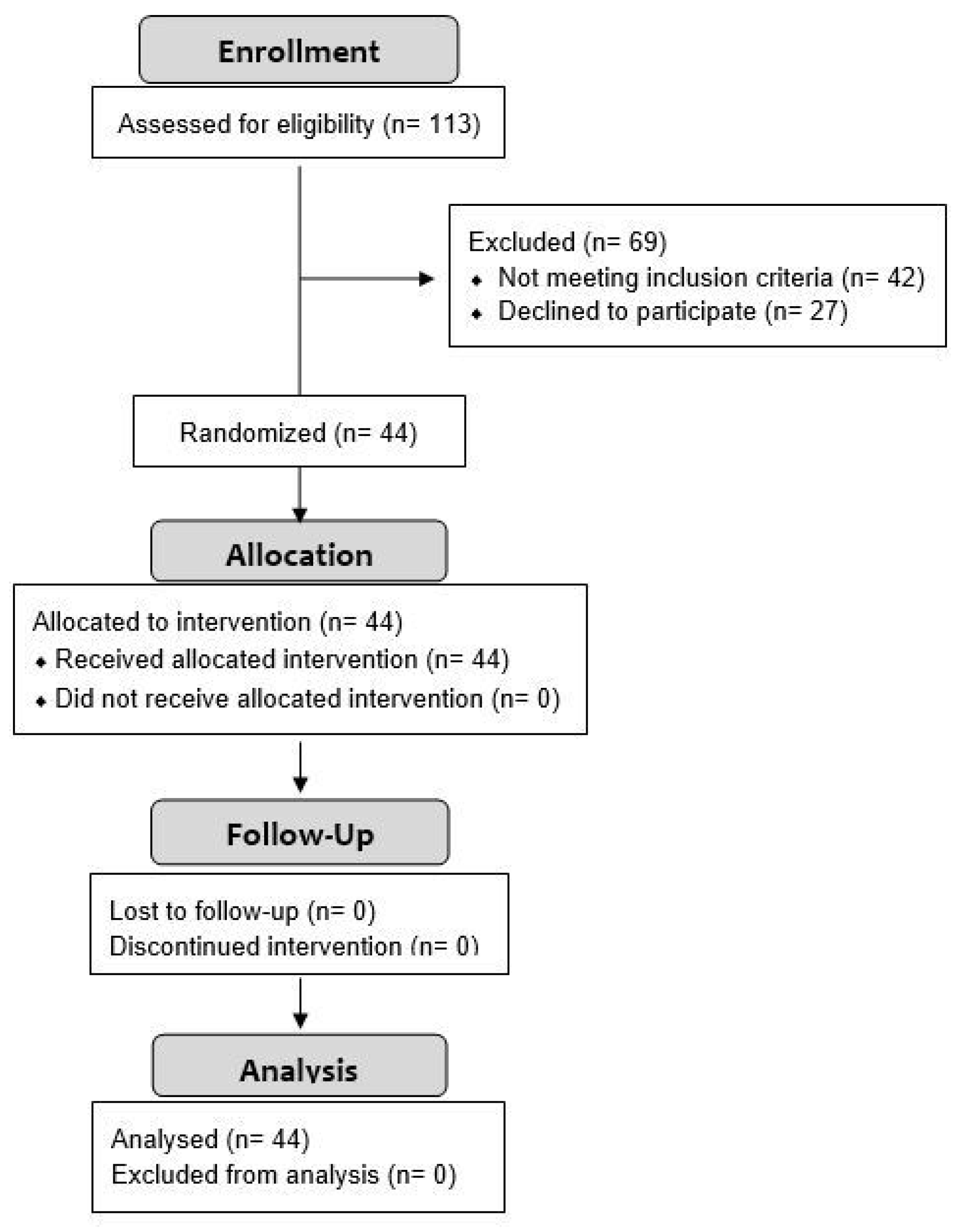

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Intervention

2.4. Outcome Measures

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

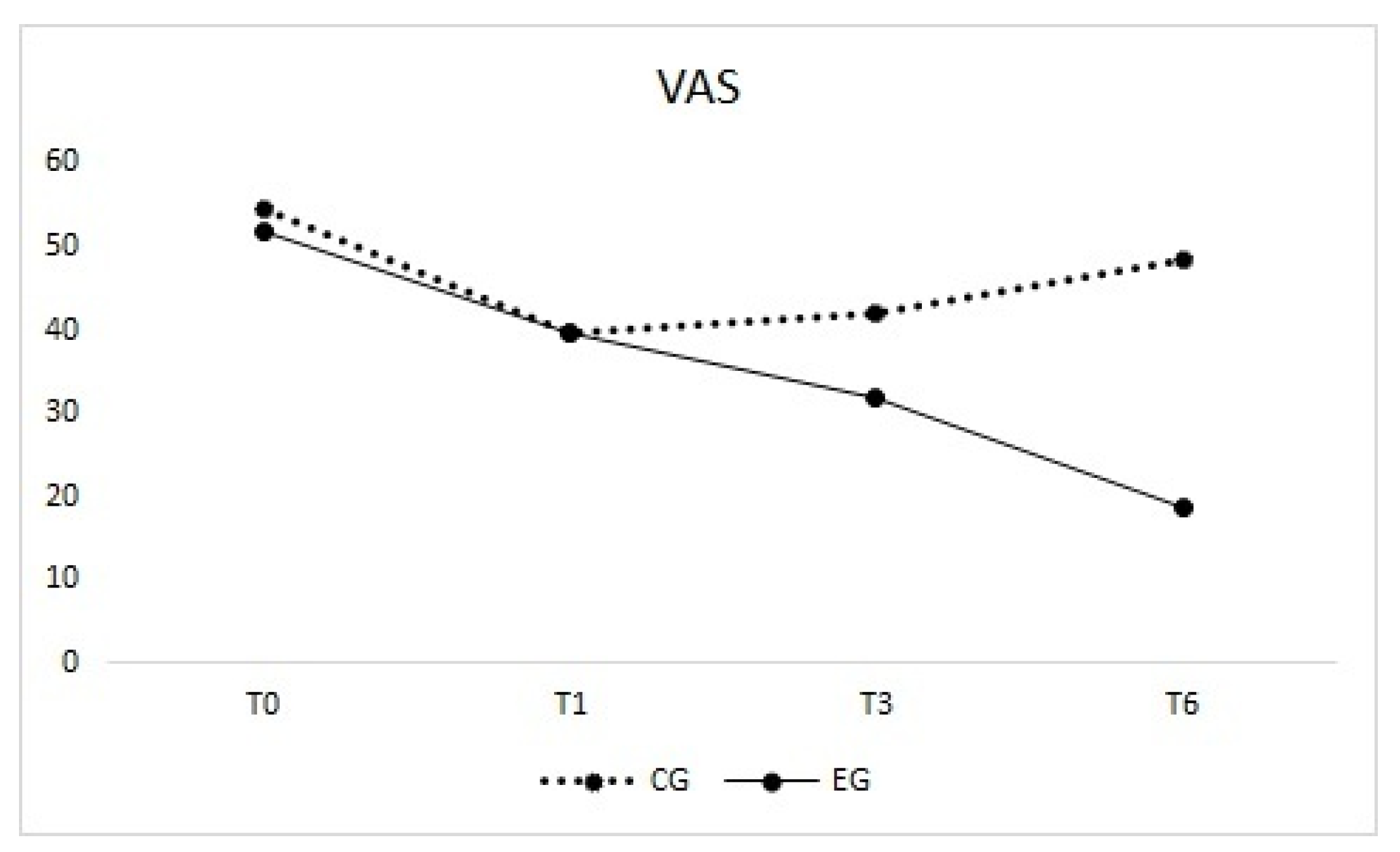

3.1. Visual Analogue Scale (Primary Outcome)

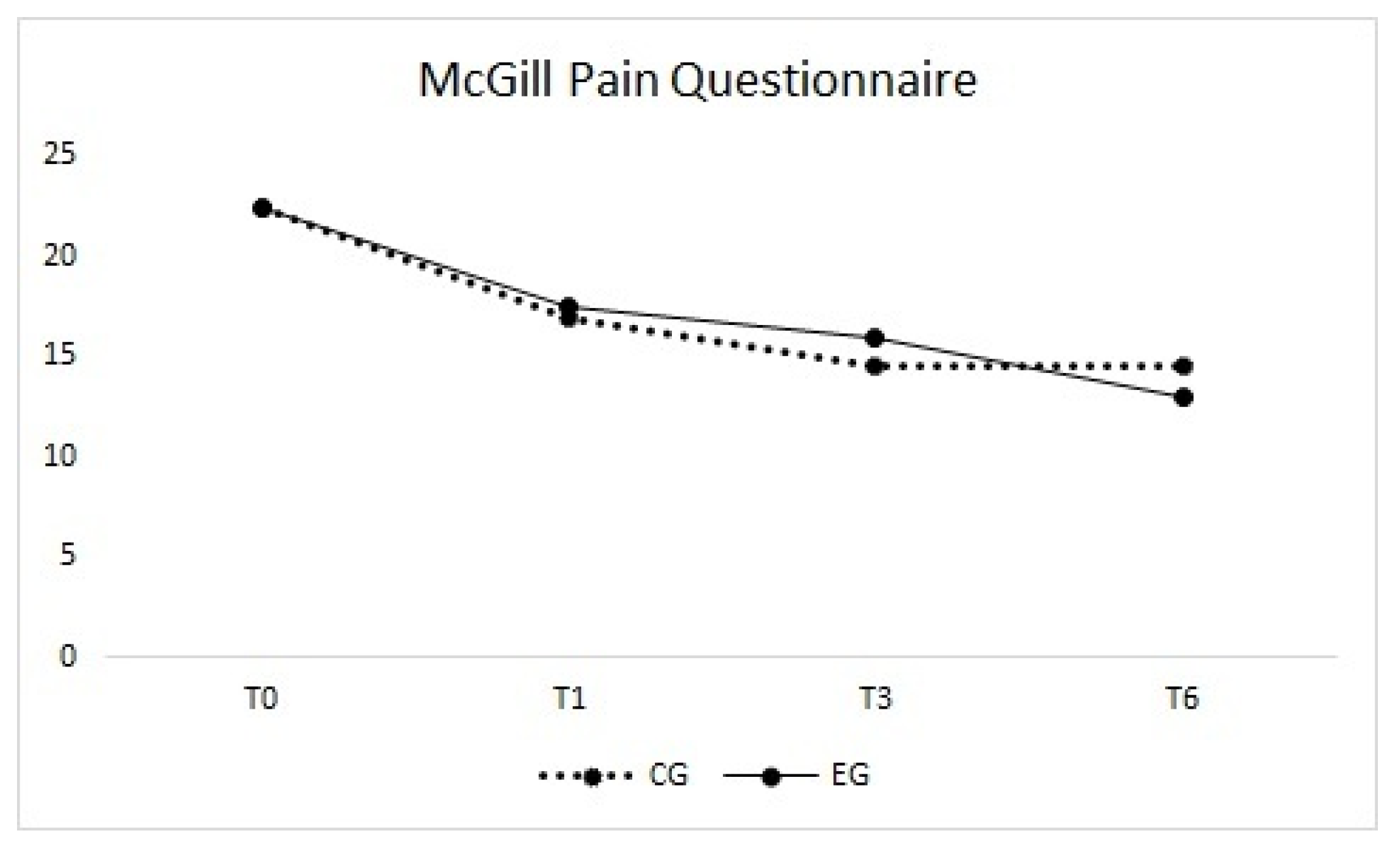

3.2. McGill Pain Questionnaire

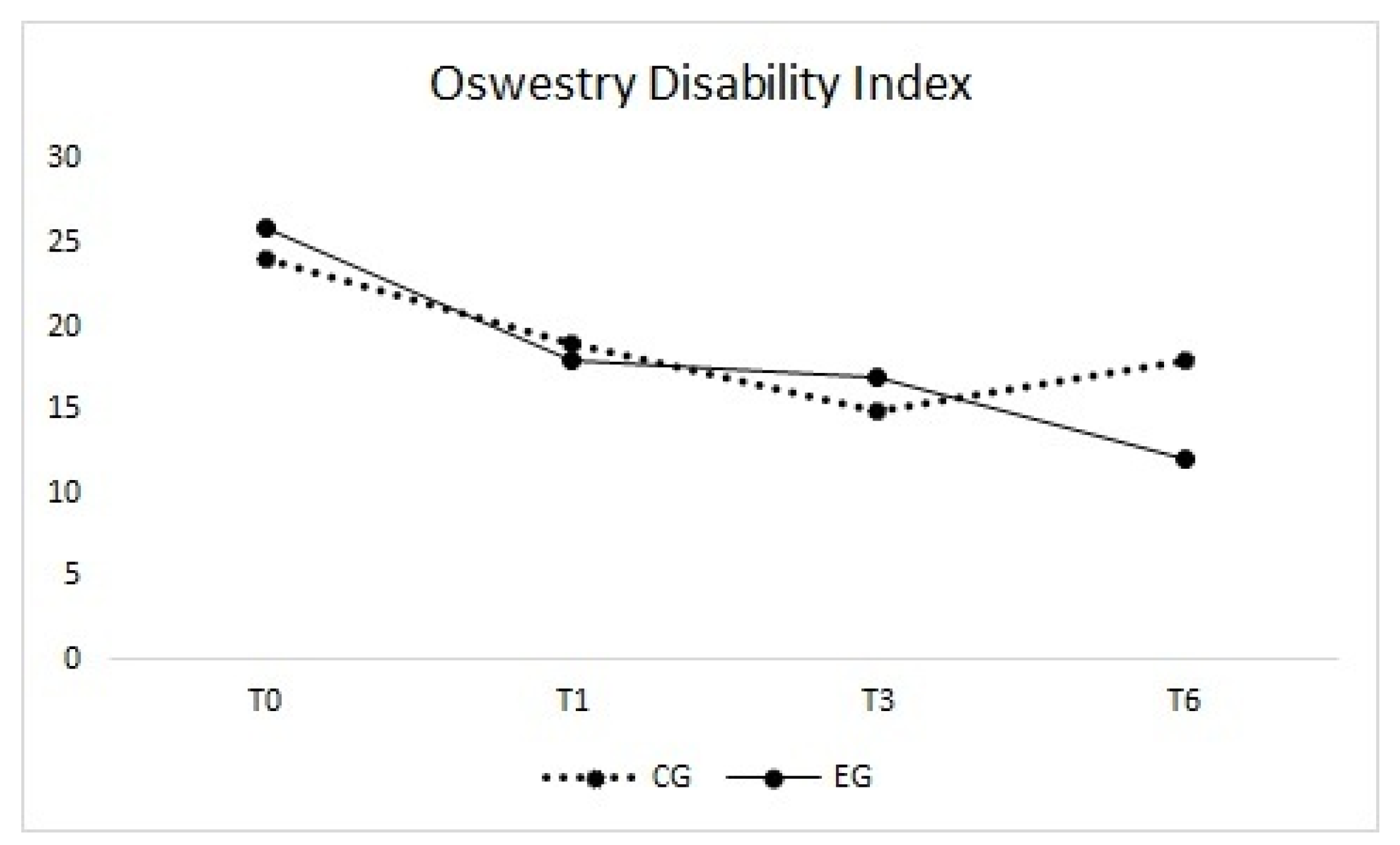

3.3. Oswestry Disability Index

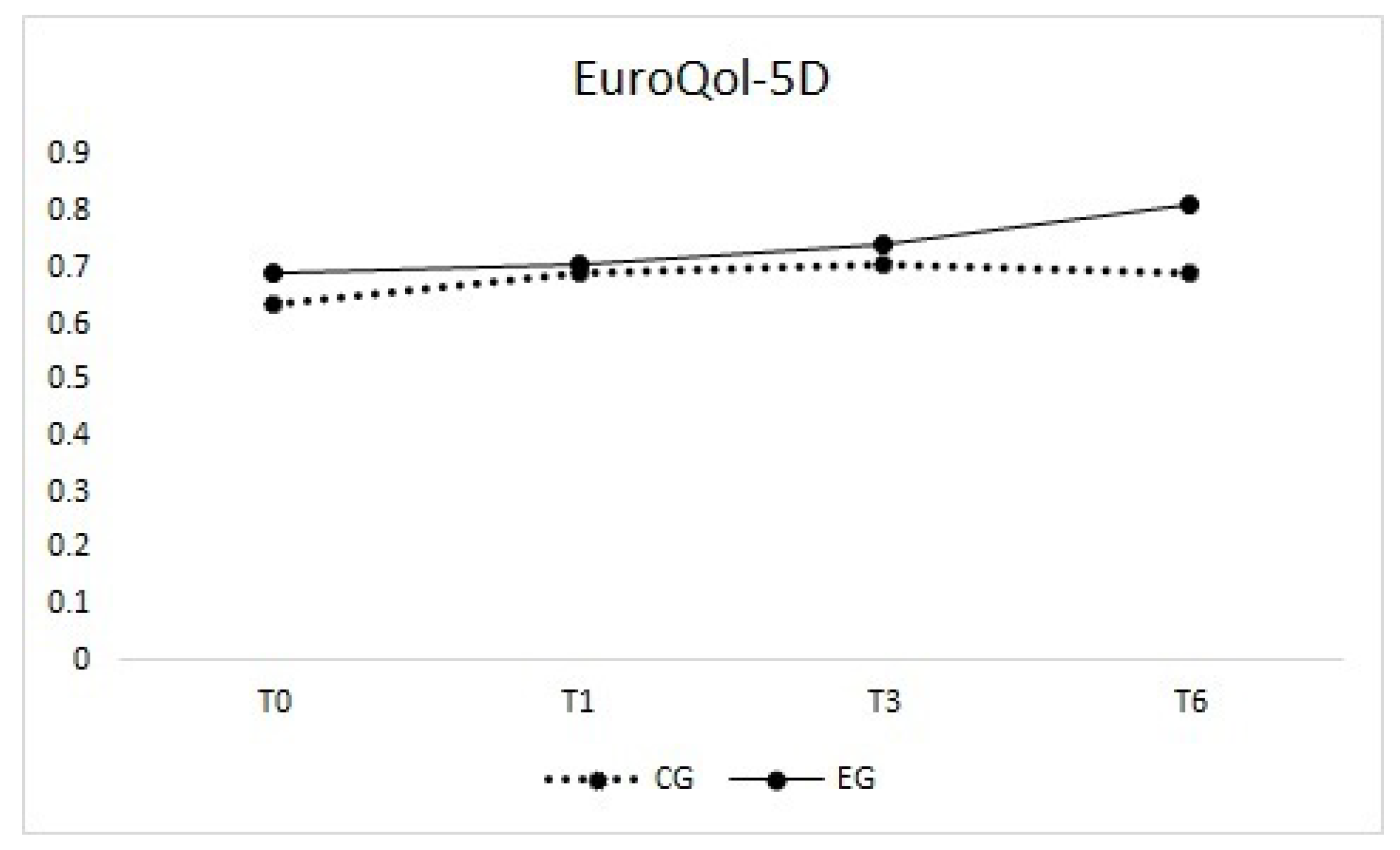

3.4. EuroQol-5D

3.5. Adverse Effects

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andersson, G.B. Epidemiological features of chronic low-back pain. Lancet 1999, 354, 581–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strine, T.W.; Hootman, J.M. US national prevalence and correlates of low back and neck pain among adults. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 57, 656–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchmanowicz, I.; Kołtuniuk, A.; Stępień, A.; Uchmanowicz, B.; Rosińczuk, J. The influence of sleep disorders on the quality of life in patients with chronic low back pain. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2019, 33, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snekkevik, H.; Eriksen, H.R.; Tangen, T.; Chalder, T.; Reme, S.E. Fatigue and depression in sick-listed chronic low back pain patients. Pain Med. 2014, 15, 1163–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boden, S.D.; Davis, D.O.; Dina, T.S.; Patronas, N.J.; Wiesel, S.W. Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic subjects. A prospective investigation. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 1990, 72, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkayam, O.; Ben Itzhak, S.; Avrahami, E.; Meidan, Y.; Doron, N.; Eldar, I.; Keidar, I.; Liram, N.; Yaron, M. Multidisciplinary approach to chronic back pain: Prognostic elements of the outcome. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 1996, 14, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hayden, J.A.; Wilson, M.N.; Stewart, S.; Cartwright, J.L.; Smith, A.O.; Riley, R.D.; van Tulder, M.; Tom Bendix, T.; Cecchi, F.; Costa, L.O.P.; et al. Chronic Low Back Pain IPD Meta-Analysis Group. Exercise treatment effect modifiers in persistent low back pain: An individual participant data meta-analysis of 3514 participants from 27 randomised controlled trials. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1277–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frizziero, A.; Pellizzon, G.; Vittadini, F.; Bigliardi, D.; Costantino, C. Efficacy of Core Stability in Non-Specific Chronic Low Back Pain. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2021, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martell, B.A.; O’Connor, P.G.; Kerns, R.D.; Becker, W.C.; Morales, K.H.; Kosten, T.R.; Fiellin, D.A. Systematic review: Opioid treatment for chronic back pain: Prevalence, efficacy, and association with addiction. Ann. Intern. Med. 2007, 146, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airaksinen, O.; Brox, J.I.; Cedraschi, C.; Hildebrandt, J.; Klaber-Moffett, J.; Kovacs, F.; Mannion, A.F.; Reis, S.; Staal, J.B.; Ursin, H.; et al. Chapter 4. European guidelines for the management of chronic nonspecific low back pain. Eur. Spine J. Off. Publ. Eur. Spine Soc. Eur. Spinal Deform. Soc. Sect. Cerv. Spine Res. Soc. 2006, 15 (Suppl. 2), S192–S300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, P.M.; Szczurko, O.; Cooley, K.; Mills, E.J. Cost-effectiveness of naturopathic care for chronic low back pain. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2008, 14, 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Musial, F.; Michalsen, A.; Dobos, G. Functional chronic pain syndromes and naturopathic treatments: Neurobiological foundations. Forsch. Komplement. 2008, 15, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, A.; Eschman, J.; Ge, W. Acupressure for chronic low back pain: A single system study. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2017, 29, 1416–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chen, Y.W.; Wang, H.H. The effectiveness of acupressure on relieving pain: A systematic review. Pain Manag. Nurs. Off. J. Am. Soc. Pain Manag. Nurses 2014, 15, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monson, E.; Arney, D.; Benham, B.; Bird, R.; Elias, E.; Linden, K.; McCord, K.; Miller, C.; Miller, T.; Ritter, L.; et al. Beyond Pills: Acupressure Impact on Self-Rated Pain and Anxiety Scores. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2019, 25, 517–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godley, E.; Smith, M.A. Efficacy of acupressure for chronic low back pain: A systematic review. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2020, 39, 101146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsson, E.M.; von Schéele, B. Relaxing on a bed of nails: An exploratory study of the effects on the autonomic, cardiovascular, and respiratory systems, and saliva cortisol. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2011, 17, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hohmann, C.; Ullrich, I.; Lauche, R.; Choi, K.E.; Lüdtke, R.; Rolke, R.; Cramer, H.; Saha, F.J.; Rampp, T.; Michalsen, A.; et al. The benefit of a mechanical needle stimulation pad in patients with chronic neck and lower back pain: Two randomized controlled pilot studies. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. eCAM 2012, 2012, 753583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, T.M.; Gharaibeh, B.; Huard, J. Stem cells, angiogenesis and muscle healing: A potential role in massage therapies? Br. J. Sports Med. 2013, 47, 556–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musial, F.; Spohn, D.; Rolke, R. Naturopathic reflex therapies for the treatment of chronic back and neck pain—Part 1: Neurobiological foundations. Forsch. Komplement. 2013, 20, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graven-Nielsen, T.; Arendt-Nielsen, L. Assessment of mechanisms in localized and widespread musculoskeletal pain. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2010, 6, 599–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, A.; Hoggart, B. Pain: A review of three commonly used pain rating scales. J. Clin. Nurs. 2005, 14, 798–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melzack, R. The McGill Pain Questionnaire: Major properties and scoring methods. Pain 1975, 1, 277–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbank, J.C.; Pynsent, P.B. The Oswestry Disability Index. Spine 2000, 25, 2940–2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balestroni, G.; Bertolotti, G. L’EuroQol-5D (EQ-5D): Uno strumento per la misura della qualità della vita (EuroQol-5D (EQ-5D): An instrument for measuring quality of life). Monaldi Arch. Chest Dis. Arch. Monaldi Mal. Torace 2012, 78, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akritas, M.G.; Brunner, E. A unified approach to rank tests for mixed models. J. Stat. Plan. Inference 1997, 61, 249–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, D.A.; Madden, L.V. Nonparametric analysis of ordinal data in designed factorial experiments. Phytopathology 2004, 94, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Guideline Centre (UK). Low Back Pain and Sciatica in over 16s: Assessment and Management; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Koes, B.W.; van Tulder, M.; Lin, C.W.; Macedo, L.G.; McAuley, J.; Maher, C. An updated overview of clinical guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care. Eur. Spine J. Off. Publ. Eur. Spine Soc. Eur. Spinal Deform. Soc. Eur. Sect. Cerv. Spine Res. Soc. 2010, 19, 2075–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupeyron, A.; Ribinik, P.; Gélis, A.; Genty, M.; Claus, D.; Hérisson, C.; Coudeyre, E. Education in the management of low back pain: Literature review and recall of key recommendations for practice. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2011, 54, 319–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, D.S.; Moseley, G.L. Explain Pain, 2nd ed.; Noigroup Publications: Adelaide, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Searle, A.; Spink, M.; Ho, A.; Chuter, V. Exercise interventions for the treatment of chronic low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Clin. Rehabil. 2015, 29, 1155–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, N.E.; Anema, J.R.; Cherkin, D.; Chou, R.; Cohen, S.P.; Gross, D.P.; Ferreira, P.H.; Fritz, J.M.; Koes, B.W.; Peul, W.; et al. Prevention and treatment of low back pain: Evidence, challenges, and promising directions. Lancet 2018, 391, 2368–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urits, I.; Burshtein, A.; Sharma, M.; Testa, L.; Gold, P.A.; Orhurhu, V.; Viswanath, O.; Jones, M.R.; Sidransky, M.A.; Spektor, B.; et al. Low Back Pain, a Comprehensive Review: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2019, 23, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, P.J.; Miller, C.T.; Mundell, N.L.; Verswijveren, S.; Tagliaferri, S.D.; Brisby, H.; Bowe, S.J.; Belavy, D.L. Which specific modes of exercise training are most effective for treating low back pain? Network meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1279–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, P.B. Lumbar segmental ‘instability’: Clinical presentation and specific stabilizing exercise management. Man. Ther. 2000, 5, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodges, P.W.; Richardson, C.A. Inefficient muscular stabilization of the lumbar spine associated with low back pain. A motor control evaluation of transversus abdominis. Spine 1996, 21, 2640–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannion, A.F.; Helbling, D.; Pulkovski, N.; Sprott, H. Spinal segmental stabilisation exercises for chronic low back pain: Programme adherence and its influence on clinical outcome. Eur. Spine J. Off. Publ. Eur. Spine Soc. Eur. Spinal Deform. Soc. Eur. Sect. Cerv. Spine Res. Soc. 2009, 18, 1881–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarán-Peñarrocha, G.A.; Lara Palomo, I.C.; Antequera Soler, E.; Gil-Martínez, E.; Fernández-Sánchez, M.; Aguilar-Ferrándiz, M.E.; Castro-Sánchez, A.M. Comparison of efficacy of a supervised versus non-supervised physical therapy exercise program on the pain, functionality and quality of life of patients with non-specific chronic low-back pain: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2020, 34, 948–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfort, G.; Maiers, M.J.; Evans, R.L.; Schulz, C.A.; Bracha, Y.; Svendsen, K.H.; Grimm, R.H., Jr.; Owens, E.F., Jr.; Garvey, T.A.; Transfeldt, E.E. Supervised exercise, spinal manipulation, and home exercise for chronic low back pain: A randomized clinical trial. Spine J. Off. J. N. Am. Spine Soc. 2011, 11, 585–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjellgren, A.; Erdefelt, K.; Werngren, L.; Norlander, T. Does relaxation on a bed of nails (spike mat) induce beneficial effects? A randomized controlled pilot study. Altern. Med. Stud. 2011, 1, e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purepong, N.; Channak, S.; Boonyong, S.; Thaveeratitham, P.; Janwantanakul, P. The effect of an acupressure backrest on pain and disability in office workers with chronic low back pain: A randomized, controlled study and patients’ preferences. Complement. Ther. Med. 2015, 23, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilberter, T.; Roman, J. Reflexo-therapy with mechanical skin stimulation: Pilot study. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Integrative Medicine, New York, NY, USA, 26–28 May 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Treede, R.D.; Kenshalo, D.R.; Gracely, R.H.; Jones, A.K. The cortical representation of pain. Pain 1999, 79, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moseley, L.G.; Zalucki, N.M.; Wiech, K. Tactile discrimination, but not tactile stimulation alone, reduces chronic limb pain. Pain 2008, 137, 600–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moseley, L.G. I can’t find it! Distorted body image and tactile dysfunction in patients with chronic back pain. Pain 2008, 140, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.S.; Cholewicki, J.; Reeves, N.P.; Zazulak, B.T.; Mysliwiec, L.W. Comparison of trunk proprioception between patients with low back pain and healthy controls. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2010, 91, 1327–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morone, G.; Iosa, M.; Paolucci, T.; Fusco, A.; Alcuri, R.; Spadini, E.; Saraceni, V.M.; Paolucci, S. Efficacy of perceptive rehabilitation in the treatment of chronic nonspecific low back pain through a new tool: A randomized clinical study. Clin. Rehabil. 2012, 26, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | CG | EG |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 16 (72.7%) | 15 (68.2%) |

| Male | 6 (27.3%) | 7 (31.8%) |

| Age (years) | ||

| Mean ± SD | 58.9 ± 15.2 | 56.6 ± 15.8 |

| Median (min–max) | 57.0 (22.0–80.0) | 59.5 (26.0–80.0) |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | ||

| Mean ± SD | 26.4 ± 3.4 | 25.3 ± 3.7 |

| Median (min–max) | 27.3 (18.7–29.8) | 24.9 (18.1–29.8) |

| Years since the onset of symptoms | ||

| Mean ± SD | 15.2 ± 12.7 | 14.4 ± 15.3 |

| Median (min–max) | 14.0 (1.0–40.0) | 8.5 (0.5–60.0) |

| VAS at T0 | ||

| Mean ± SD | 52.5 ± 27.7 | 50.0 ± 21.9 |

| Median (min–max) | 54.5 (3.0–98.0) | 52.0 (12.0–98.0) |

| McGill Pain Questionnaire at T0 | ||

| Mean ± SD | 25.4 ± 14.9 | 24.7 ± 12.2 |

| Median (min–max) | 22.5 (3.0–54.0) | 22.5 (7.0–51.0) |

| Oswestry Disability Index at T0 | ||

| Mean ± SD | 28.4 ± 15.0 | 28.6 ± 13.9 |

| Median (min–max) | 24.0 (4.0–52.0) | 26.0 (10.0–66.0) |

| EuroQol-5D at T0 | ||

| Mean ± SD | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.3 |

| Median (min–max) | 0.6 (−0.2 to 0.8) | 0.7 (−0.1 to 0.8) |

| Variable | Time | Control Group (CG) | Experimental Group (EG) | Median of Delta (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Median (Min-Max) | Mean ± SD | Median (Min–Max) | |||

| Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) | T0 | 52.5 ± 27.7 | 54.5 (3.0–98.0) | 50.0 ± 21.9 | 52.0 (12.0–98.0) | −2 (−20;11) |

| T1 | 44.6 ± 29.6 | 39.5 (3.0–94.0) | 39.3 ± 23.8 | 39.5 (8.0–95.0) | −5 (−24;11) | |

| T3 | 42.0 ± 27.0 | 42.0 (2.0–92.0) | 33.2 ± 24.2 | 32.0 (2.0–96.0) | −8.5 (−26;6) | |

| T6 | 42.8 ± 27.3 | 48.5 (5.0–91.0) | 25.8 ± 23.5 | 18.5 (0.0–82.0) | −17.5 (−37;0) | |

| McGill Pain Questionnaire | T0 | 25.4 ± 14.9 | 22.5 (3.0–54.0) | 24.7 ± 12.2 | 22.5 (7.0–51.0) | 0 (−10;8) |

| T1 | 19.5 ± 14.0 | 17.0 (3.0–50.0) | 19.4 ± 10.0 | 17.5 (6.0–47.0) | 2 (−7;8) | |

| T3 | 16.5 ± 11.8 | 14.5 (2.0–52.0) | 17.9 ± 12.1 | 16.0 (0.0–46.0) | 2 (−5;8) | |

| T6 | 17.5 ± 12.9 | 14.5 (1.0–51.0) | 14.0 ± 11.1 | 13.0 (0.0–47.0) | −2 (−9;4) | |

| Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) | T0 | 28.4 ± 15.0 | 24.0 (4.0–52.0) | 28.6 ± 13.9 | 26.0 (10.0–66.0) | 0 (−8;10) |

| T1 | 23.2 ± 14.2 | 19.0 (2.0–56.0) | 22.1 ± 12.8 | 18.0 (6.0–58.0) | 0 (−8;6) | |

| T3 | 21.4 ± 14.5 | 15.0 (4.0–56.0) | 18.7 ± 13.8 | 17.0 (0.0–54.0) | −2 (−10;6) | |

| T6 | 22.8 ± 14.6 | 18.0 (6.0–54.0) | 15.7 ± 13.5 | 12.0 (0.0–46.0) | −6 (−16;0) | |

| EuroQol−5D | T0 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 0.6 (−0.2 to 0.8) | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 0.7 (−0.1 to 0.8) | 0.03 (−0.07;0.11) |

| T1 | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 0.7 (−0.2 to 0.9) | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.7 (−0.0 to 0.9) | 0.00 (−0.09;0.12) | |

| T3 | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 0.7 (−0.2 to 0.9) | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 0.7 (0.1–0.9) | 0.09 (0.00;0.18) | |

| T6 | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 0.7 (−0.2 to 0.9) | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 0.8 (0.3–1.0) | 0.12 (0.00;0.24) | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Frizziero, A.; Finotti, P.; Scala, C.L.; Morone, G.; Piran, G.; Masiero, S. Efficacy of an Acupressure Mat in Association with Therapeutic Exercise in the Management of Chronic Low Back Pain: A Prospective Randomized Controlled Study. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5211. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11115211

Frizziero A, Finotti P, Scala CL, Morone G, Piran G, Masiero S. Efficacy of an Acupressure Mat in Association with Therapeutic Exercise in the Management of Chronic Low Back Pain: A Prospective Randomized Controlled Study. Applied Sciences. 2021; 11(11):5211. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11115211

Chicago/Turabian StyleFrizziero, Antonio, Paolo Finotti, Cinzia La Scala, Giovanni Morone, Giovanni Piran, and Stefano Masiero. 2021. "Efficacy of an Acupressure Mat in Association with Therapeutic Exercise in the Management of Chronic Low Back Pain: A Prospective Randomized Controlled Study" Applied Sciences 11, no. 11: 5211. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11115211

APA StyleFrizziero, A., Finotti, P., Scala, C. L., Morone, G., Piran, G., & Masiero, S. (2021). Efficacy of an Acupressure Mat in Association with Therapeutic Exercise in the Management of Chronic Low Back Pain: A Prospective Randomized Controlled Study. Applied Sciences, 11(11), 5211. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11115211