Finite Element Analysis of the Milling of Ti6Al4V Titanium Alloy Laser Additive Manufacturing Parts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Finite Element Model

2.1. J-C Constitutive Model

2.2. Modified Coulomb Friction Stress Model

2.3. Chip Separation Guidelines

2.4. Basic Settings of the Finite Element

- (1)

- Ti6Al4V titanium alloy material is isotropic;

- (2)

- set the tool to a rigid body, only consider the heat conduction of the tool, and ignore the deformation and friction loss of the tool;

- (3)

- during the milling process, the vibration of the tool and workpiece caused by environmental factors is not considered.

3. The Results of the Numerical Experiment

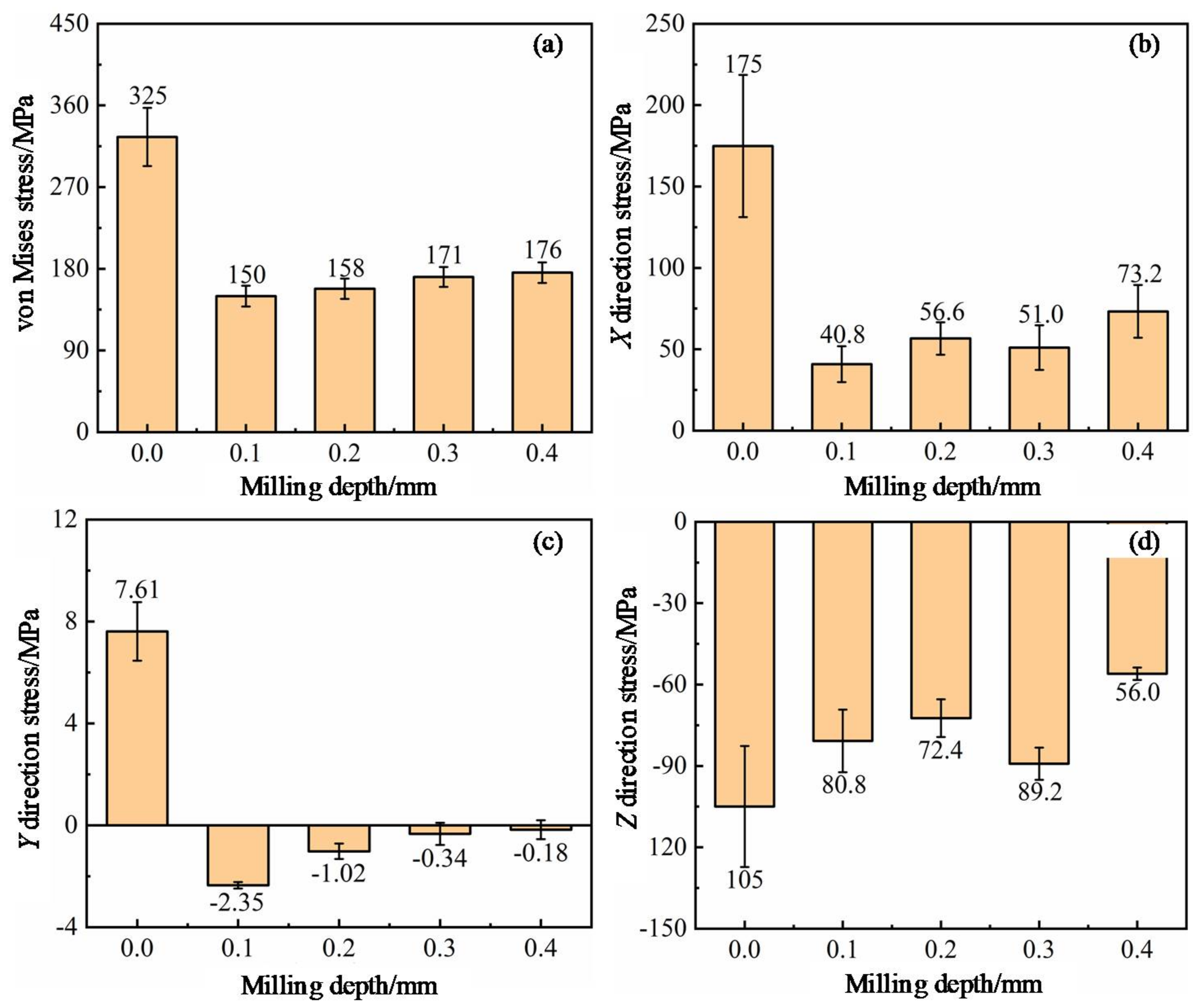

3.1. Residual Stress Analysis

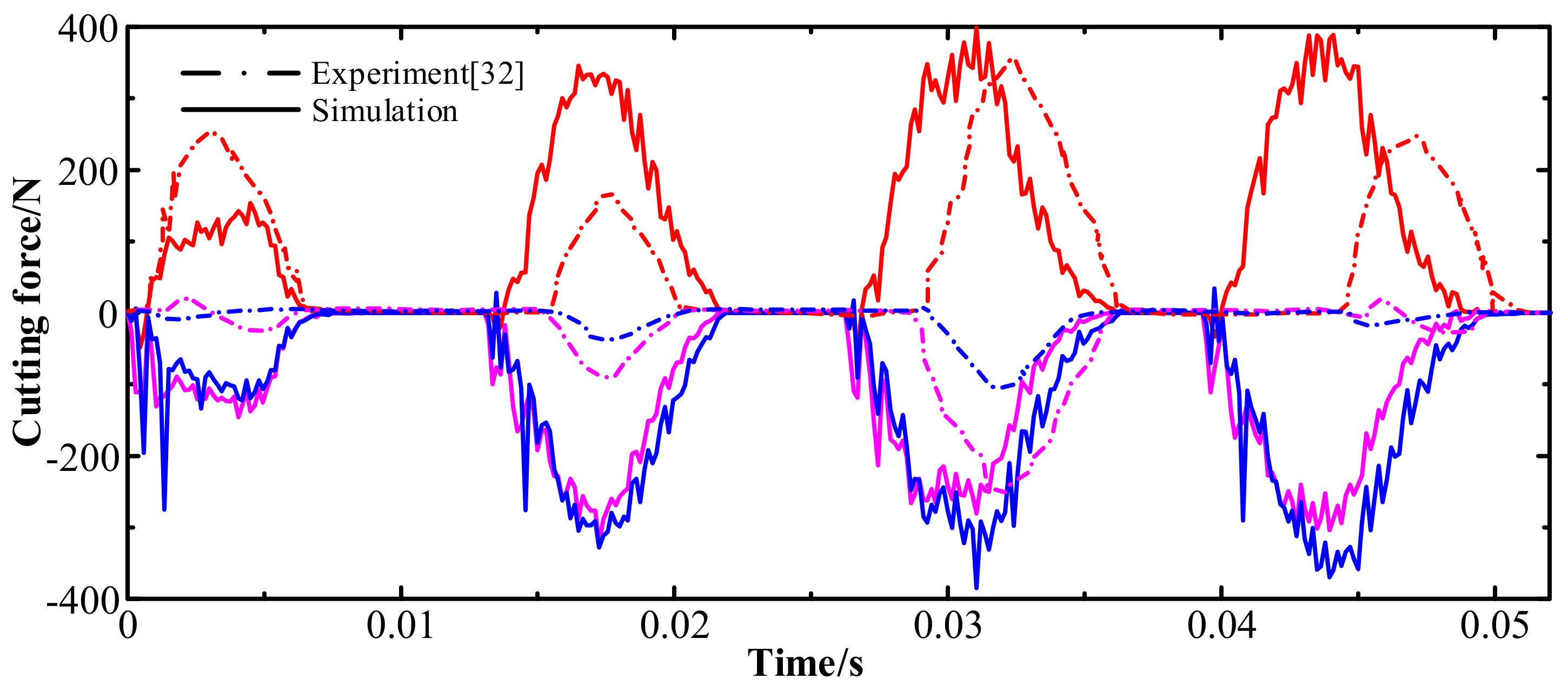

3.2. Model Validity Verification

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Milling processes change the distribution state of residual stress in the cladding layer, which can reduce the tensile stress generated by additive manufacturing processes and even change it into compressive stress. Meanwhile, the residual stress distribution on the surface of the milling layer is more uniform, and the anisotropy is greatly improved. The equivalent Mises stress is reduced by 47% on average compared with that of the original forming surface.

- (2)

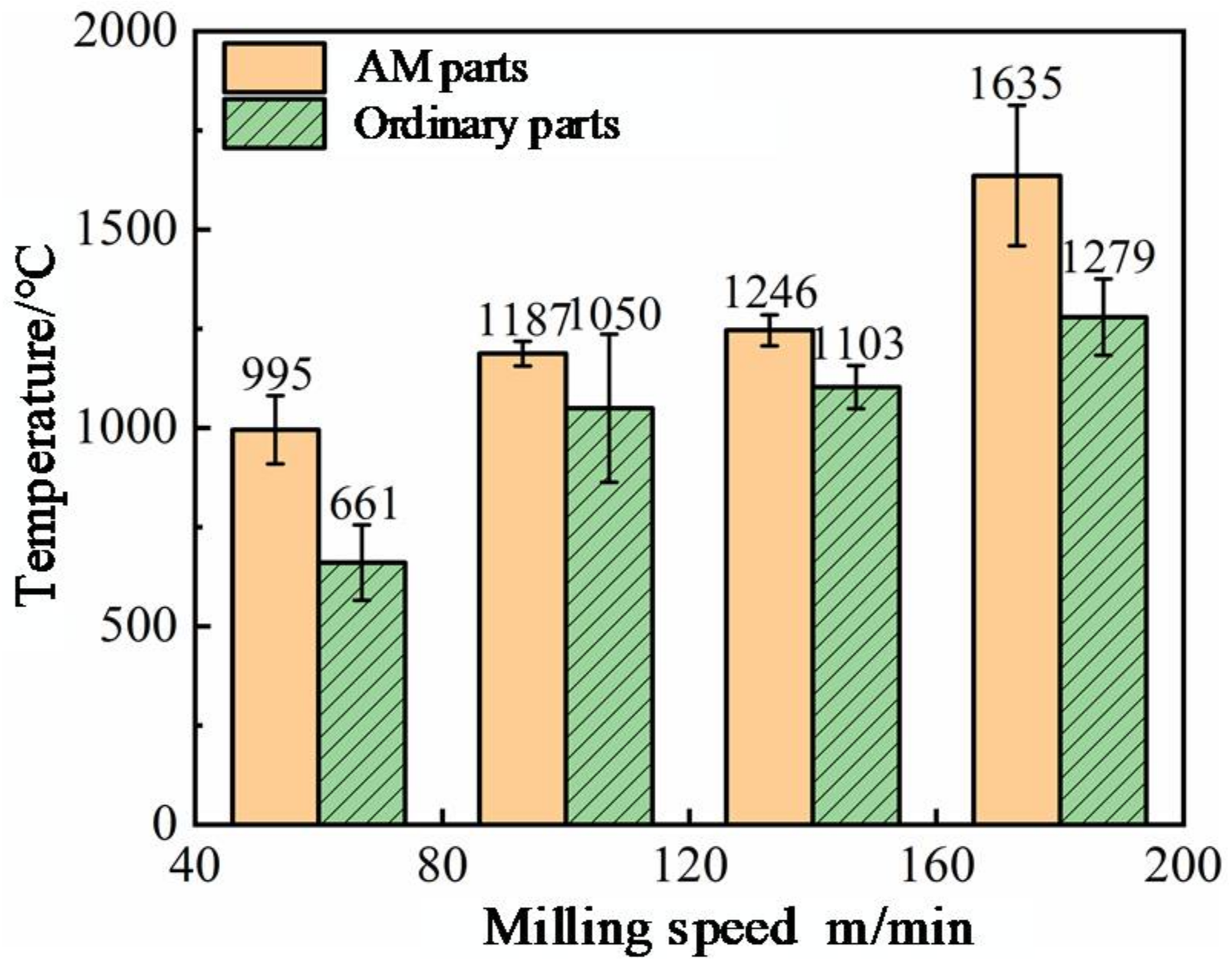

- At different milling speeds, the milling peak temperature of additive manufacturing parts is higher than that of forging parts, and the milling temperature gradually increases when the milling speed increases. Under the same processing conditions, the milling peak temperature of the additive manufacturing Ti6Al4V titanium alloy milling model increases by about 26.2%.

- (3)

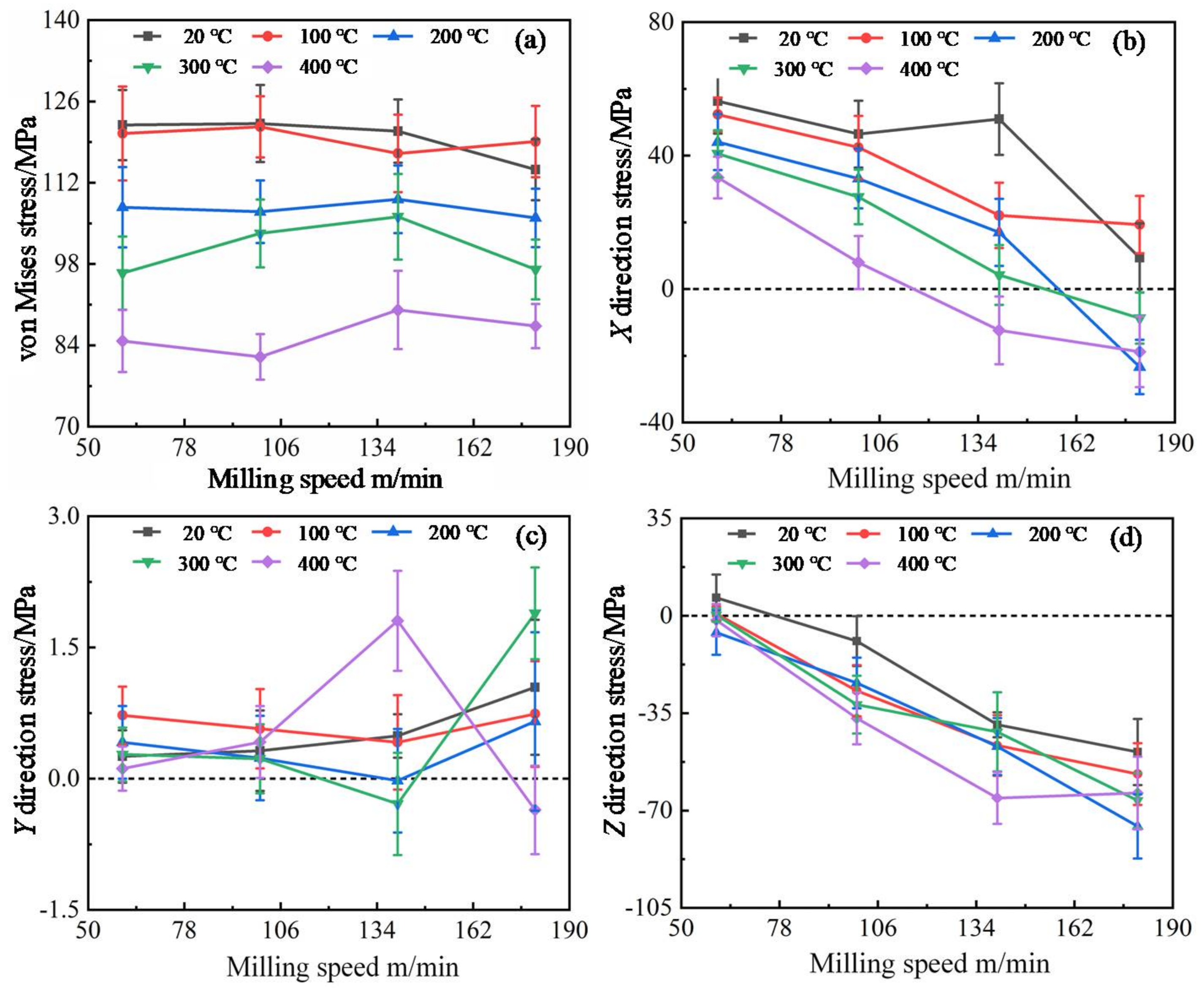

- The residual stress on the milling surface decreases with an increase in the initial temperature. When the initial temperature increases from room temperature to 400 °C, the maximum Mises stress of the milling surface decreases by 26% on average, the X direction stress decreases by 136.5% on average, and the residual tensile stress decreases significantly.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| SLM | Selective laser melting |

| EBM | Electron beam melted |

| DMLS | Direct metal laser sintering |

| J-C | Johnson-Cook constitutive model |

| A | Initial yield stress |

| B | Strain hardening parameter |

| C | Strain rate hardening parameter |

| n | Hardening index |

| m | Thermal softening index |

| Equivalent plastic strain rate | |

| Reference strain rate | |

| Tr | Ambient temperature |

| Tm | Ti6Al4V melting point |

| τf | Friction stress |

| μ | Friction coefficient |

| τs | Ultimate shear stress of the material |

| σn | Normal stress on the contact surface |

| Equivalent plastic strain coefficient increment | |

| Equivalent strain when the material fails | |

| Reference strain rate | |

| σm | Average normal stress |

| Equivalent stress | |

| vc | Milling speed |

| ae | Cutting depth |

References

- Zhang, Q.S.; Li, C.G.; Li, S.; Sui, S.; Wang, E.T. Research status and prospect of laser additive manufacturing technology for titanium alloy. Hot Work. Tech. 2018, 47, 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Aremu, A.; Ashcroft, I.; Wildman, R.; Hague, R.; Tuck, C.; Brackett, D. The effects of bidirectional evolutionary structural optimization parameters on an industrial designed component for additive manufacture. Proc. Ins. Mech. Eng. 2013, 227, 794–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maskery, I.; Aremu, A.; Simonelli, M.; Tuck, C.; Wildman, R.; Ashcroft, I.; Hague, R. Mechanical properties of Ti-6Al-4V selectively laser melted parts with body-centred-cubic lattices of varying cell size. Exp. Mech. 2015, 55, 1261–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.D.; Liu, R.H. Research development of 3D printing for large complex metal parts. Ordnan. Ind. Auto. 2017, 36, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Mok, S.H.; Bi, G.; Folkes, J.; Pashby, I. Deposition of Ti-6Al-4V using a high power diode laser and wire, Part I: Investigation on the process characteristics. Surf. Coat. Tech. 2008, 202, 3933–3939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimenov, D.Y.; Mia, M.; Gupta, M.K.; Machado, A.R.; Tomaz, Í.V.; Sarikaya, M.; Wojciechowski, S.; Mikolajczyk, T.; Kapłonek, W. Improvement of machinability of Ti and its alloys using cooling-lubrication techniques: A review and future prospect. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 11, 719–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, A.K.; Zhang, X.; Davis, A.E.; Kennedy, J.R.; Martina, F.; Ding, J.; Williams, S.; Prangnell, P.B. Effect of deposition strategies on fatigue crack growth behaviour of wire + arc additive manufactured titanium alloy Ti–6Al–4V. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 814, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, H.; Jiang, Y.S.; Wang, Q.; Wu, Y.; Xiong, J.; Dong, S.Y. Research progress in stress and deformation control in laser additive manufacturing for high-performance metals. J. Mater. Eng. 2019, 47, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, T.A.; Duarte, V.; Miranda, R.M.; Santos, T.G.; Oliveira, J.P. Current Status and Perspectives on Wire and Arc Additive Manufacturing (WAAM). Materials 2019, 12, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, L.; Yin, J.; Zhu, H.; Peng, G.; Sun, J.; Chen, C.; Wang, G.; Li, Z.; Zeng, X. Numerical simulation of stress evolution of thin-wall titanium parts fabricated by selective laser melting. Acta Metall. Sin. 2020, 56, 374–384. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, X.H.; Zhang, H.O.; Wang, G.L. Metal direct prototyping by using hybrid plasma deposition and milling. J. Mater. Process. Tech. 2009, 209, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Tian, H.; Chen, S.; Li, F. Review on precision control technologies of additive manufacturing hybrid subtractive process. Acta Metall. Sin. 2020, 56, 83–98. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Y.W.; Zhao, Q.; Li, X.L. The key technology and development of the compound processing of adding and reducing materials. MW Met. Cut. 2016, 13, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Du, W.; Bai, Q.; Zhang, B. A novel method for additive/subtractive hybrid manufacturing of metallic parts. In Proceedings of the 44th North American Manufacturing Research Conference, Virginia Polytechnic & State University, Blacksburg, VA, USA, 27 June–1 July 2016; pp. 1018–1030. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.J.; Song, B.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, L.C.; Wei, Q.S.; Shi, Y.S. Aisi 420 stainless steel fabricated by laser selective melting additive and machining: Evolution of surface roughness and residual stress. J. Mech. Eng. 2018, 54, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, J.; Machado, C.M.; Duarte, V.R.; Rodrigues, T.A.; Santos, T.G.; Oliveira, J. Effect of milling parameters on HSLA steel parts produced by Wire and Arc Additive Manufacturing (WAAM). J. Manuf. Process. 2020, 59, 739–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordin, A.; Imbrogno, S.; Rotella, G.; Bruschi, S.; Ghiotti, A.; Umbrello, D. Finite element simulation of semi-finishing turning of electron beam melted Ti6Al4V under dry and cryogenic cooling. In Proceedings of the 15th CIRP Conference on Modelling of Machining Operations, Karlsruhe, Germany, 11–12 June 2015; pp. 551–556. [Google Scholar]

- Imbrogno, S.; Rinaldi, S.; Raso, A.; Bordin, A.; Bruschi, S.; Umbrello, D. 3D FE simulation of semi-finishing machining of Ti6Al4V additively manufactured by direct metal laser sintering. In Proceedings of the 21st International ESAFORM Conference on Material Forming, Palermo, Italy, 23–25 April 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bordin, A.; Bruschi, S.; Ghiotti, A.; Bucciotti, F.; Facchini, L. Comparison between wrought and EBM Ti6Al4V machinability characteristics. In Proceedings of the 17th Conference of the European-Scientific-Association-on-Material-Forming, Espoo, Finland, 7–9 May 2014; pp. 1186–1193. [Google Scholar]

- Shunmugavel, M.; Polishetty, A.; Goldberg, M.; Singh, R.; Littlefair, G. A comparative study of mechanical properties and machinability of wrought and additive manufactured (selective laser melting) titanium alloy-Ti-6Al-4V. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2017, 23, 1051–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milton, S.; Morandeau, A.; Chalon, F.; Leroy, R. Influence of finish machining on the surface integrity of Ti6Al4V produced by selective laser melting. Proc. CIRP 2016, 45, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polishetty, A.; Shunmugavel, M.; Goldberg, M.; Littlefair, G.; Singh, R.K. Cutting force and surface finish analysis of machining additive manufactured titanium alloy Ti-6A1-4V. Proc. Manuf. 2017, 7, 284–289. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, G.R.; Cook, W.H. A constitutive model and data for metals subjected to large strains, high rates and high temperatures. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Symposium on Ballistics, The Hague, The Netherlands, 1 January 1983; pp. 541–547. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, G.R.; Cook, W.H. Fracture characteristics of three metals subjected to various strains, strain rates, temperatures and pressures. Eng. Fract. Mech. 1985, 21, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.F.; Zeng, X.G.; Liao, Y. Thermal-viscoplastic constitutive relation of Ti-6Al-4V alloy and numerical simulation by modified Johnson-Cook modal. Chin. J. Nonferr. Metal. 2017, 27, 1419–1425. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.B.; Zhang, S.J. 3D FEM simulation of milling process for titanium alloy Ti-6Al-4V. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Tech. 2014, 71, 1319–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.X.; Tian, X.G.; Gan, C.; Wei, B.H. Dynamic mechanical behavior of U75V steel under uniaxial compression and its modified J-C constitutive model. Trans. Mater. Heat Treat. 2019, 40, 156–164. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z. Numerical Simulation of Additive Manufacturing and Milling Performance of Titanium Alloy Laser Fuse. Master’s Thesis, Northeastern University, Shenyang, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ozel, T. The influence of friction models on finite element simulation of machining. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2006, 46, 518–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackerle, J. Finite element analysis and simulation of machining: A bibliography (1976–1996). J. Mater. Process. Technol. 1999, 86, 17–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratap, T.; Patea, K.; Dyakonov, A.A. Modeling cutting force in micro-milling of Ti-6Al-4V titanium alloy. Proc. Eng. 2015, 129, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.X.; Xu, T.; Yang, J. Finite element simulation of titanium alloy milling process. Mech. Drive 2012, 36, 33–37. [Google Scholar]

| Material | A(MPa) | B(MPa) | n | m | C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti6Al4V | 1000 | 780 | 0.47 | 1.02 | 0.033 |

| Chemical Element | Al | Si | Fe | V | C | O | N | Ti |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt% | 5.4 | 0.15 | 0.30 | 3.41 | 11.0 | 0.15 | 0.15 | Bal |

| Modulus of Elasticity (MPa) | Poisson’s Ratio | Coefficient of Linear Expansion (°C) | Specific Heat (J/kg·°C) | Coefficient of Thermal Conductivity (W/m·°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6.4 × 105 | 0.22 | 4.5 × 10−6 | 220 | 75.4 |

| D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | D5 | Tm | T0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −0.09 | 0.25 | −0.5 | 0.014 | 3.87 | 1668 °C | 20 °C |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ren, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, Z. Finite Element Analysis of the Milling of Ti6Al4V Titanium Alloy Laser Additive Manufacturing Parts. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4813. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11114813

Ren Z, Zhang X, Wang Y, Li Z, Liu Z. Finite Element Analysis of the Milling of Ti6Al4V Titanium Alloy Laser Additive Manufacturing Parts. Applied Sciences. 2021; 11(11):4813. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11114813

Chicago/Turabian StyleRen, Zhaohui, Xingwen Zhang, Yunhe Wang, Zhuhong Li, and Zhen Liu. 2021. "Finite Element Analysis of the Milling of Ti6Al4V Titanium Alloy Laser Additive Manufacturing Parts" Applied Sciences 11, no. 11: 4813. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11114813

APA StyleRen, Z., Zhang, X., Wang, Y., Li, Z., & Liu, Z. (2021). Finite Element Analysis of the Milling of Ti6Al4V Titanium Alloy Laser Additive Manufacturing Parts. Applied Sciences, 11(11), 4813. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11114813