Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Internationalisation Strategies: A Descriptive Study in the Spanish Context

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. CSR and Internationalisation

2.1. CSR: Concept and Characteristics

2.2. Internationalization: Concept and Characteristics

2.3. Strategic Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility and Internationalisation

Higher Visibility

Risk Mitigation

Availability of Funds

Learning and Maximisation of Skills Valuable for Meeting the Expectations of the Stakeholders

- Good Reputation Associated with CSR

- Adapting to New Environments

3. Descriptive Analysis

3.1. Sample

3.2. Measuring Variables

3.3. Methodology

3.4. Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aguilera-Caracuel, Javier, Mª Ángeles Escudero Torres, Nuria Esther Hurtado Torres, and María Dolores Vidal Salazar. 2011. La influencia de la diversificación y experiencia internacional en la estrategia medioambiental proactiva de las empresas. Investigaciones Europeas de Dirección y Economía de la Empresa 17: 75–91. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilera-Caracuel, Javier, Blanca Luisa Delgado Márquez, Vidal Salazar, and María Dolores. 2014. Influencia de la internacionalización en el desempeño social de las empresas. Cuadernos de Gestión 14: 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera-Caracuel, Javier, Jaime Guerrero-Villegas, María Dolores Vidal-Salazar, and Blanca L. Delgado-Márquez. 2015. International cultural diversification and corporate social performance in multinational enterprises: The role of slack financial resources. Journal Management International Review 55: 323–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allouche, José, and Patrice Laroche. 2005. A meta-analytical investigation of the relationship between corporate social and financial performance. Revue de Gestion dess Ressources Humaines 57: 18–41. [Google Scholar]

- Antonacopoulou, Elena P., and Jérôme Meric. 2005. From power to knowledge relationships: Stakeholder interactions as learning partnerships. In Stakeholders and Corporate Social Responsibility: European Perspectives. Edited by M. Bonnafous-Boucher and Y. Pesqueux. London: Macmillan, pp. 125–47. [Google Scholar]

- Aw, B-Y., and Amy Ruey-meng Hwang. 1995. Productivity and the export market: A firm-level analysis. Journal of Development Economics 47: 313–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aw, Bee Yan, Sukkyun Chung, and Mark J. Roberts. 2000. Productivity and turnover in the export market: Micro evidence from Taiwan and South Korea. The World Bank Economic Review 14: 65–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagnoli, Mark, and Susan G. Watts. 2003. Selling to socially responsible consumers: Competition and the private provision of public goods. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy 12: 419–45. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal, Pratima. 2005. Evolving sustainably: A longitudinal study of corporate sustainable. Strategic Management Journal 26: 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkema, Harry G., and Freek Vermeulen. 1998. International expansion through start-up or acquisition: A learning perspective. Academy of Management Journal 41: 7–26. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, Michael L. 2007. Stakeholder influence capacity and the variability of financial returns to corporate social responsibility. Academy of Management Review 32: 794–816. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, Michael L. 2016. The business case for corporate social responsibility. A critique and an indirect path forward. Business & Society, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, Jay. 1991. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management 17: 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, Andrew B., and J. Bradford Jensen. 1999. Exceptional exporter performance: Cause, effect, or both? Journal of International Economics 47: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, Andrew B., and Joachim Wagner. 1997. Exports and success in German manufacturing. Weltwirtshaftliches Archiv 133: 134–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, Andrew B., J. Bradford Jensen, and Robert Z. Lawrence. 1995. Exporters, jobs and wages in US Manufacturing, 1976–1987. The Brooking Papers on Economic Activity: Microeconomics 1995: 67–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besley, Timothy, and Maitreesh Ghatak. 2007. Retailing public goods: The economics of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Public Economics 91: 1645–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondy, Krista, Jeremy Moon, and Dirk Matten. 2012. An institution of corporate social responsibility (CSR) in multi-national companies (MNCs): Form and implications. Journal of Business Ethics 111: 281–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camisón, César, and Ana Villar-López. 2010. Effect of SMEs’ international experience on foreign intensity and economic performance: The mediating role of internationally exploitable assets and competitive strategy. Journal of Small Business Management 48: 116–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Joanna Tochman, Lorraine Eden, and Stewart R. Miller. 2012. Multinationals and corporate social responsibility in host countries: Does distance matter? Journal of International Business Studies 43: 84–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrión Maroto, Juan. 2007. Estrategia: De la Visión de Acción. Madrid: ESIC editorial. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, Archie B. 1991. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Business Horizons 34: 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, Archie B. 1999. Corporate social responsibility: Evolution of a definitional construct. Business and Society 38: 268–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, Archie, and Ann Buchholtz. 2006. Business and Society: Ethics and Stakeholder Management, 6th ed. Mason: Thomson South-Western. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Ricky YK, and Katherine HY Ma. 2016. Environmental Orientation of Exporting SMEs from an Emerging Economy: Its Antecedents and Consequences. Management International Review 56: 597–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, Wing S., and Yang Chen. 2012. Corporate sustainable development: Testing a new scale based on the mainland Chinese context. Journal of Business Ethics 105: 519–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, Max E. 1995. A stakeholder framework for analyzing and evaluating corporate social performance. Academy of Management Review 20: 92–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, Philip L. 2007. The evolution of corporate social responsibility. Business Horizons 50: 449–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta, Patricia, Sergio Contreras, Liliana Pedraja, and José Navas. 2015. Influencia del grado de internacionalización sobre los resultados empresariales. Revista de Ciencias Estratégicas 24: 53–71. [Google Scholar]

- Correa-López, M., and R. Doménech. 2012. La internacionalización de las empresas españolas. Documentos de Trabajo BBVA Research, December 29. [Google Scholar]

- Crouch, Colin. 2006. Modelling the firm in its market and organizational environment: Methodologies for studying corporate social responsibility. Organization Studies 27: 1533–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahan, Nicolas, Jonathan Doh, and Terrence Guay. 2006. The role of multinational corporations in transnational institution building: A policy network perspective. Human Relations 59: 1571–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlsrud, Alexander. 2008. How corporate social responsibility is defined: An analysis of 37 definitions. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 15: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, Catherine M., S. Trevis Certo, and Dan R. Dalton. 2000. International experience in the executive suite: The path to prosperity? Strategic Management Journal 21: 515–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, John D., and Jeffrey Bracker. 1989. Profit performance: Do foreign operations make a difference? Management International Review 29: 46–56. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, Miguel A., Jose C. Farinas, and Sonia Ruano. 2002. Firm productivity and export markets: A non parametric approach. Journal of International Economics 57: 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, Thomas, and Lee E. Preston. 1995. The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Academy of Management Review 20: 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, Kathleen M., and Jeffrey A. Martin. 2000. Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strategic Management Journal 21: 1105–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escuela de Estrategia Empresarial. 2014. Qué es la Internacionalización de las Empresas? Available online: https://www.escueladeestrategia.com/que-es-la-internacionalizacion-de-empresas/ (accessed on 8 April 2018).

- European Parliament. 2013. Report of the Committee on Employment and Social Affairs on Corporate Social Responsibility: Promoting society’s interests and a route to sustainable and inclusive recovery (2012/2097(INI)). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2013:0207:FIN:EN:PDF (accessed on 29 September 2018).

- Farinas, José C., and Ana Martín-Marcos. 2007. Exporting and economic performance: Firm-level evidence of Spanish manufacturing. The World Economy 30: 618–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández López, María. 2016. Responsabilidad Social Corporativa Estratégica de los Recursos Humanos Basada en alto Compromiso y Resultados Organizativos: Un Modelo Integrador. Ph.D. thesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain. Available online: http://eprints.ucm.es/40615/1/T38184.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2018).

- Fernández, Zulima, and María J. Nieto. 2005. Internationalization strategy of small and medium-sized family businesses: Some influential factors. Family Business Review 18: 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, Charles, and Mark Shanley. 1990. What’s in a name? Reputation building and corporate strategy. Academy of Management Journal 33: 233–58. [Google Scholar]

- Forética. 2015. Informe Forética 2015 Sobre el Estado de la RSE en España. Ciudadano Consciente, Empresas Sostenibles. Available online: http://foretica.org/informe_foretica_2015.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2018).

- Freeman, R. Edward. 1984. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Boston: Pitman. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R. Edward, Jeffrey S. Harrison, Andrew C. Wicks, Bidhan L. Parmar, and Simone De Colle. 2010. Stakeholder Theory: The State of the Art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Galbreath, Jeremy. 2006. Does primary stakeholder management positively affect the bottom line? Some evidence from Australia. Management Decision 44: 1106–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, Francisco, and Lucía Avella Camarero. 2008. La influencia de la exportación sobre los resultados empresariales: Análisis de las pymes manufactureras españolas en el período 1990–2002. Revista Europea de Dirección y Economía de la Empresa 17: 85–104. [Google Scholar]

- García-Canal, Esteban, Mauro Guillén, and Ana Valdés-Llaneza. 2012. La internacionalización de la empresa española. Perspectivas empíricas. Papeles de Economía Española 132: 64–81. [Google Scholar]

- Garriga, Elisabet, and Domènec Melé. 2004. Corporate social responsibility theories: Mapping the territory. Journal of Business Ethics 53: 52–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geppert, Mike, Dirk Matten, and Peter Walgenbach. 2006. Transnational institution building and the multinational corporation: An emerging field of research. Human Relations 59: 1451–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geringer, Michael J., Paul W. Beamish, and Richard C. DaCosta. 1989. Diversification strategy and internationalization: Implications for MNE performance. Strategic Management Journal 10: 109–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, Belén, Cristina López-Duarte, and Marta María Vidal-Suárez. 2013. Cooperación e internacionalización: El caso de ALSA. Revista de Historia Industrial 55: 170–72. [Google Scholar]

- Gregorio, Raúl. 2013. Herramientas de Gestión para la Responsabilidad Social Corporativa. Trabajo fin de Máster. Universidad de Valladolid. Available online: https://uvadoc.uva.es/bitstream/10324/6500/1/TFM-P-109.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2018).

- Guerras, Luis Ángel, and José Emilio Navas. 2015. La Dirección Estratégica de la Empresa: Teoría y Aplicaciones, 5th ed. Madrid: Thomson Reuters-Civitas. [Google Scholar]

- Hah, Kristin, and Susan Freeman. 2013. Multinational enterprise subsidiaries and their CSR: A conceptual framework of the management of CSR in smaller emerging economies. Journal of Business Ethics 122: 125–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, Amy J., and Gerald D. Keim. 2001. Source shareholder value, stakeholder management, and social issues: What’s the bottom line? Strategic Management Journal 22: 125–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husted, Bryan W., and David B. Allen. 2007. Strategic corporate social responsibility and value creation among large firms. lessons from the Spanish experience. Long Range Planning 40: 594–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infante, Rivas H. 2015. Responsabilidad Social Corporativa o Empresarial. Gestiopolis. Available online: https://www.gestiopolis.com/responsabilidad-social-corporativa-o-empresarial/ (accessed on 9 April 2018).

- Jamali, Dima. 2010. The CSR of MNC subsidiaries in developing countries: Global, local, substantive or diluted. Journal of Business Ethics 93: 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Thomas M. 1995. Instrumental stakeholder theory: A synthesis of ethics and economics. Academy of Management Review 20: 404–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keinert, Christina. 2008. Corporate Social Responsibility as an International Strategy. Contributions to Economics. Berlin: Springer Company. [Google Scholar]

- Key, Susan. 1999. Toward a new theory of the firm: A critique of stakeholder “theory”. Management Decision 37: 317–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Andrew A., and Christopher L. Tucci. 2002. Incumbent entry into new market niches: The role of experience and managerial choice in the creation of dynamic capabilities. Management Science 48: 171–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laudal, Thomas. 2011. Drivers and barriers of CSR and the size and internationalization of firms. Social Responsibility Journal 7: 234–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Ho-Uk, and Jong-Hun Park. 2006. Top team diversity, internationalization and the mediating effect of international alliances. British Journal of Management 17: 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Duarte, Cristina, and Esteban García-Canal. 2007. Stock market reaction to foreign direct investments: Interaction between entry mode and FDI attributes. Management International Review 47: 393–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhok, Anoop. 1997. Cost, value and foreign market entry mode: The transaction and the firm. Strategic Management Journal 18: 39–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maignan, Isabelle, and David A. Ralston. 2002. Corporate social responsibility in Europe and the US: Insights from businesses self-presentations. Journal of International Business Studies 33: 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majocchi, Antonio, and Antonella Zucchella. 2005. Internationalization and performance. International Small Business Journal 21: 249–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, Naresh K. 1981. A scale to measure self-concepts, person concepts and product concepts. Journal of Marketing Research 18: 456–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manner, Mikko H. 2010. The impact of CEO characteristics on corporate social performance. Journal of Business Ethics 93: 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, Joshua D., Hillary Anger Elfenbein, and James P. Walsh. 2007. Does It Pay to Be Good? A Meta-Analysis and Redirection of Research on the Relationship between Corporate Social and Financial Performance. Working Paper, Harvard Business School, Boston, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Matten, Dirk, and Jeremy Moon. 2008. ‘Implicit’ and ‘explicit’ CSR: A conceptual framework for a comparative understanding of corporate social responsibility. Academy of Management Review 33: 404–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, Abagail, and Donald Siegel. 2001. Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Academy of Management Review 26: 117–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishina, Yuri, Emily S. Block, and Michael J. Mannor. 2012. The path dependence of organizational reputation: How social judgment influences assessments of capability and character. Strategic Management Journal 33: 459–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, Ronald K., Bradley R. Agle, and Donna J. Wood. 1997. Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Academy of Management Review 22: 853–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mithani, Murad A. 2017. Liability of foreignness, natural disasters, and corporate philanthropy. Journal of International Business Studies 48: 941–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nummela, Niina, Kaisu Puumalainen, and Sami Saarenketo. 2005. International growth orientation of knowledge-intensive SMEs. Journal of International Entrepreneurship 3: 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlitzky, Marc, Frank L. Schmidt, and Sara L. Rynes. 2003. Corporate social and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Organization Studies 24: 403–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, Anirvan, and J. Ramachandran. 2017. Navigating identity duality in multinational subsidiaries: A paradox lens on identity claims at Hindustan Unilever 1959–2015. Journal of International Business Studies 48: 664–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrero, Y. 2014. La estrategia de Internacionalización: Análisis Comparativo de los Mecanismos de Entrada en Mercados Exteriores de seis Empresas que Operan en Diferentes Sectores de la Economía. Trabajo fin de Master. Universidad de Barcelona. pp. 31–35. Available online: http://diposit.ub.edu/dspace/bitstream/2445/66261/1/TFM_MOI_Pedrero-Yolanda-jun2015.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2018).

- Peng, Mike W., and Andrew Delios. 2006. What determines the scope of the firm over time and around the world? An Asia Pacific Perspective. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 23: 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pla, José, and A. Cobos. 2002. La aceleración del proceso de internacionalización de la empresa: El caso de las international new ventures. ICE Sector Exterior Español 802: 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Pla, José, and Fidel León. 2004. Dirección de Empresas Internacionales. Madrid: Pearson Educación, p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, Michael E., and Mark R. Kramer. 2006. The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harvard Business Review 84: 78–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Porter, Michael E., and Mark R. Kramer. 2011. Creating Shared Value. Harvard Business Review 89: 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Becerra, Puerto, and Doria Patricia. 2010. La globalización y el crecimiento empresarial a través de estrategias de internacionalización. Pensamiento & Gestión 28: 171–95. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Aleson, Marisa, and Manuel Antonio Espitia-Escuer. 2001. The effect of international diversification strategy on the performance of Spanish-Based firms during the period 1991–1995. Management International Review 41: 291–315. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas, Jose Luis, Monika Hamori, and Margarita Mayo. 2009. Board composition and firm internationalization. Academy of Management Proceedings 1: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, Andrea. 2015. Estrategias de Crecimiento en Empresas Multinacionales. Trabajo fin de Grado, Universidad de León. Available online: https://buleria.unileon.es/bitstream/handle/10612/4050/71520095P_GCI_Diciembre14.pdf.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 7 April 2018).

- Sánchez, Leticia A. Pérez-Calero, María del Mar Villegas Periñán, and Carmen Barroso Castro. 2013. El consejo de administración y la toma de decisiones internacionales. Esic Market Economics and Business Journal 44: 83–107. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, WM Gerard, and Mason A. Carpenter. 1998. Internationalization and firm governance: The roles of CEO compensation, top team composition and board structure. Academy of Management Journal 41: 158–78. [Google Scholar]

- Santonja, Aldo Olcese, Juan Alfaro, and Míguel Ángel Rodríguez. 2008. Manual de la Empresa Responsable y Sostenible. Conceptos y Herramientas de la Responsabilidad Social Corporativa o de la Empresa. Madrid: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, Sankar, Chitra Bhanu Bhattacharya, and Daniel Korschun. 2006. The role of corporate social responsibility in strengthening multiple stakeholder relationships: A field experiment. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 34: 158–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Suparn, Joity Sharma, and Arti Devi. 2009. La responsabilidad social de las empresas: El papel clave de la gestión de recursos humanos. Business Intelligence Journal 2: 205–13. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Katherine Taken, Murphy Smith, and Kun Wang. 2010. Does brand management of corporate reputation translate into higher market value? Journal of Strategic Marketing 18: 201–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, A. M. 1974. Market Signaling: Information Transfer in Hiring and Related Processes. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, Daniel. 1994. Measuring the degree of internationalization of a firm. Journal of International Business Studies 25: 325–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surroca, Jordi, Josep A. Tribó, and Sandra Waddock. 2010. Corporate responsibility and financial performance: The role of intangible resources. Strategic Management Journal 31: 463–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, Douglas E., and Lorraine Eden. 2004. What is the shape of the, multinationality-performance relationship? Multinational Business Review 12: 89–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, Jou-ying, and Chwo-Ming Joseph Yu. 1991. Export of industrial goods to Europe: The case of large Taiwanese firms. European Journal of Marketing 25: 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oosterhout, Hans, and Pursey P. M. A. R. Heugens. 2009. Much ado about nothing: A conceptual critique of corporate social responsibility. In The Oxford Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility. Edited by Andrew Crane, Dirk Matten, Abagail McWilliams, Jeremy Moon and Donald S. Siegel. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 197–223. [Google Scholar]

- Vila, Natalia, and Inés Küster. 2015. Conduce la internacionalización al éxito de una empresa familiar? Aplicación al sector textil. INNOVAR. Revista de Ciencias Administrativas y Sociales 25: 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallin Andreassen, Tor, and Bodil Lindestad. 1998. Customer loyalty and complex services: The impact of corporate image on quality, customer satisfaction and loyalty for customers with varying degrees of service expertise. International Journal of Service Industry Management 9: 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Taiyuan, and Pratima Bansal. 2012. Social responsibility in new ventures: Profiting from a long-term orientation. Strategic Management Journal 33: 1135–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Qian, Junsheng Dou, and Shenghua Jia. 2016. A meta-analytic review of corporate social responsibility and corporate financial performance: The moderating effect of contextual factors. Business & Society 55: 1083–121. [Google Scholar]

- Wan-Jan, Wan Saiful. 2006. Defining corporate social responsibility. Journal of Public Affairs 6: 176–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernerfelt, Birger. 1984. A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal 5: 171–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, Donna J. 2010. Measuring corporate social performance: A review. International Journal of Management Reviews 12: 50–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Meng-Ling. 2005. Corporate social performance, corporate financial performance and firm size: A meta-analysis. Journal of American Academy of Business 8: 163–71. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Fue, Ji Li, Hong Zhu, Zhenyao Cai, and Pengcheng Li. 2013. How international firms conduct societal marketing in emerging markets an empirical test in China. Management and International Review 53: 841–68. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | In spite of its relevance, Carroll’s model has been rationally criticised by several authors including Key (1999) and van Oosterhout and Heugens (2009), among others. |

| Does your company offer information about CSR on its website? |

| Does your company produce a report on CSR or sustainability? |

| Does the report follow the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) guidelines? |

| Is your company a signatory to the Principles of the United Nations Global Compact? |

| Is there a specific CSR department at your company? |

| Does your company have a code of ethical conduct? |

| Does your company have a permanent, bidirectional channel of communication with all interest groups or stakeholders? |

| Does your company have training programmes for employees? |

| Does your company offer work-family balance programmes? |

| Does your company have an equal opportunity and diversity plan? |

| Does your company have an internal channel for complaints so that employees can report unethical behaviour they may know about? |

| Does your company have corporate volunteer programmes? |

| Does your company have a supplier code of ethics? |

| Does your company make any type of donations or sponsor projects or activities that contribute to the general wellbeing of society? |

| Does your company have a foundation that oversees these initiatives? |

| ISO 9000 family of norms (Quality management systems) |

| ISO 14000 family of norms (Environmental management systems) |

| ISO 50001 norm (Energy management systems) |

| OHSAS 18001 standard (Occupational health and safety management system) |

| CSR_Employees | Does your company have training programmes for employees? |

| Does your company offer work-family balance programmes? | |

| Does your company have an equal opportunity and diversity plan? | |

| Does your company have an internal channel for complaints so that employees can report unethical behaviour they may know about? | |

| Does your company have corporate volunteer programmes? | |

| OHSAS 18001 standard (Occupational health and safety management system) | |

| CSR_Shareholders | Does your company offer information about CSR on its website? |

| Does your company produce a report on CSR or sustainability? | |

| Does the report follow the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) guidelines? | |

| Is your company a signatory to the Principles of the United Nations Global Compact? | |

| Does your company have a code of ethical conduct? |

| Variable | Mean | S.D. | % a | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

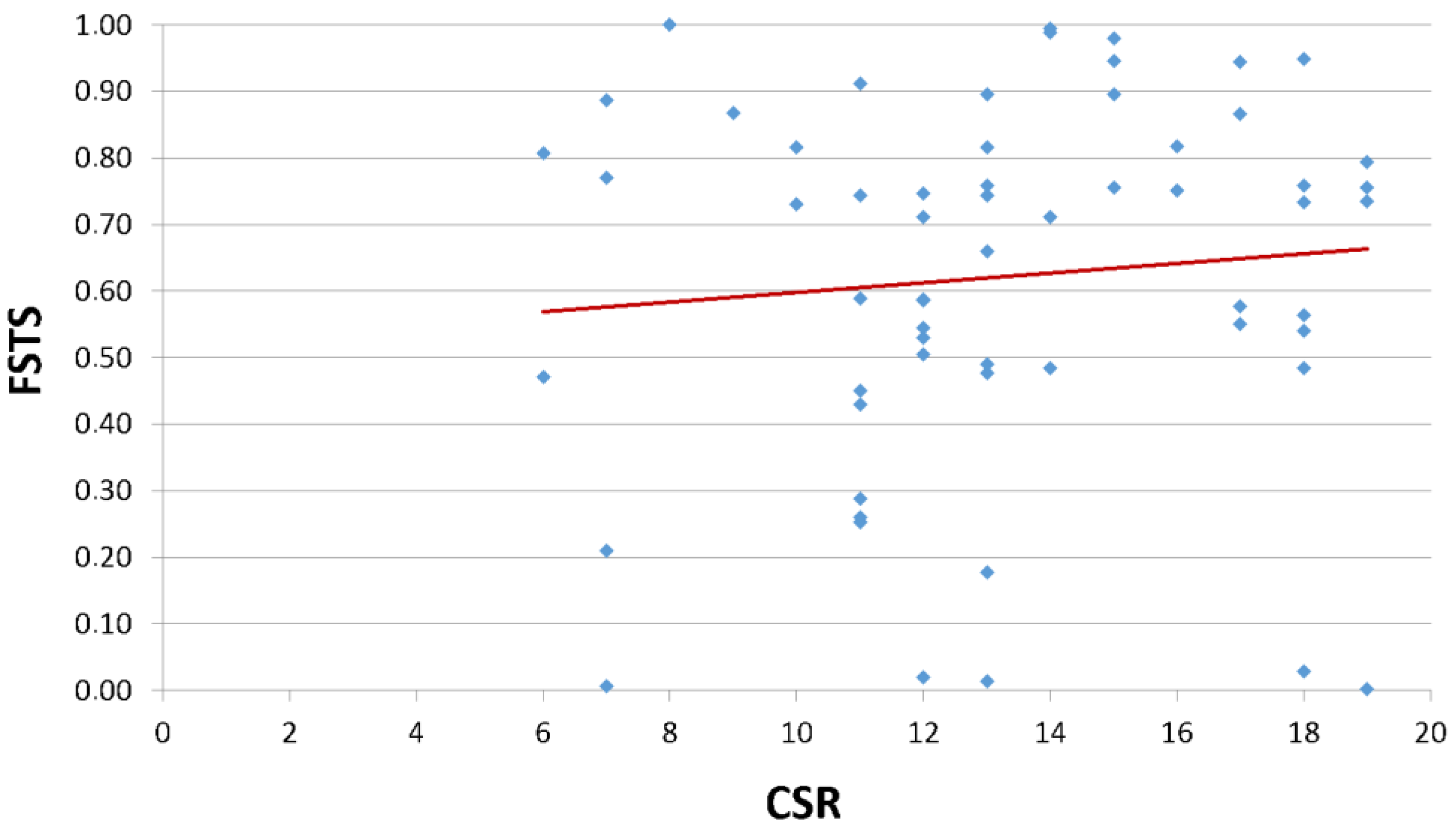

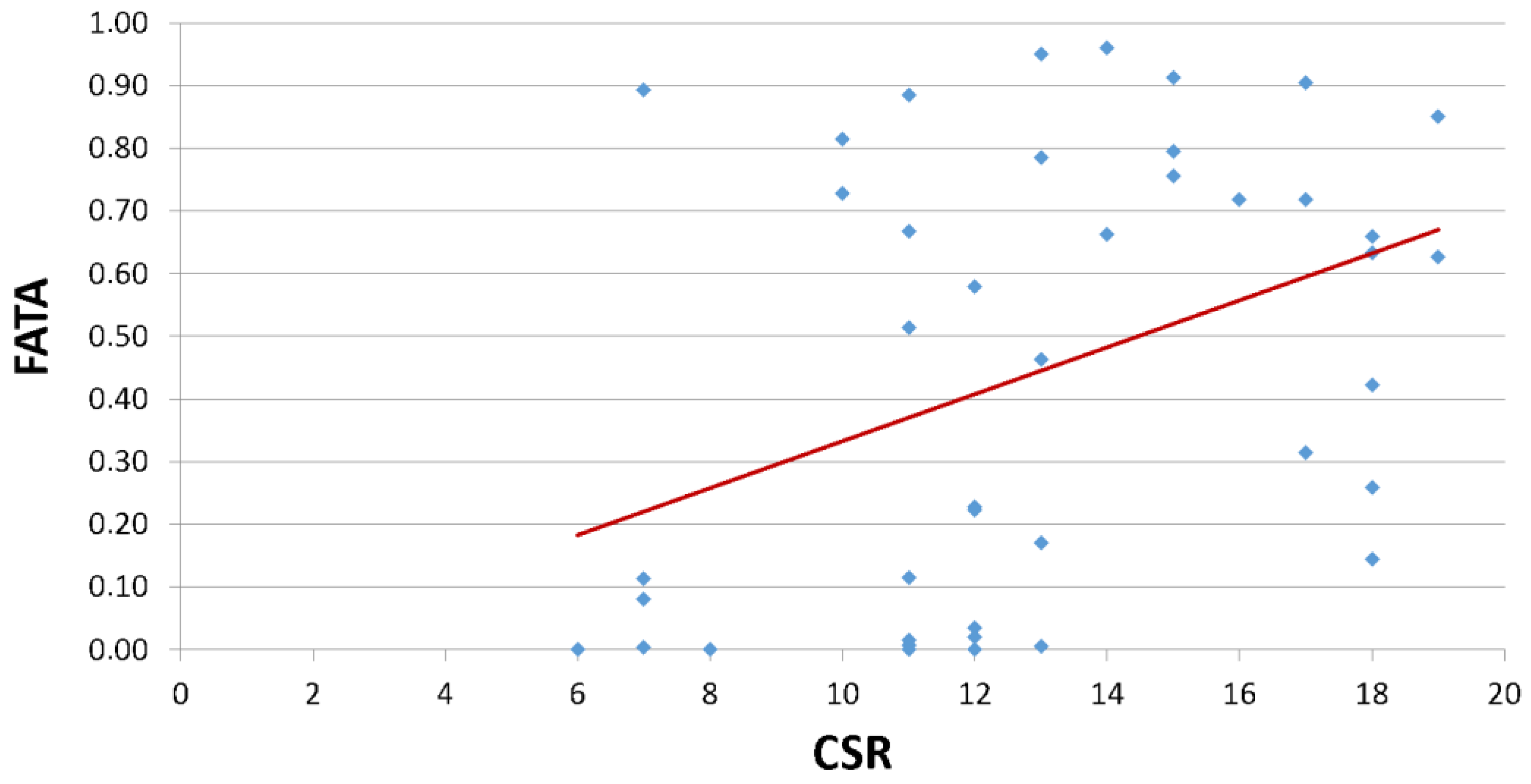

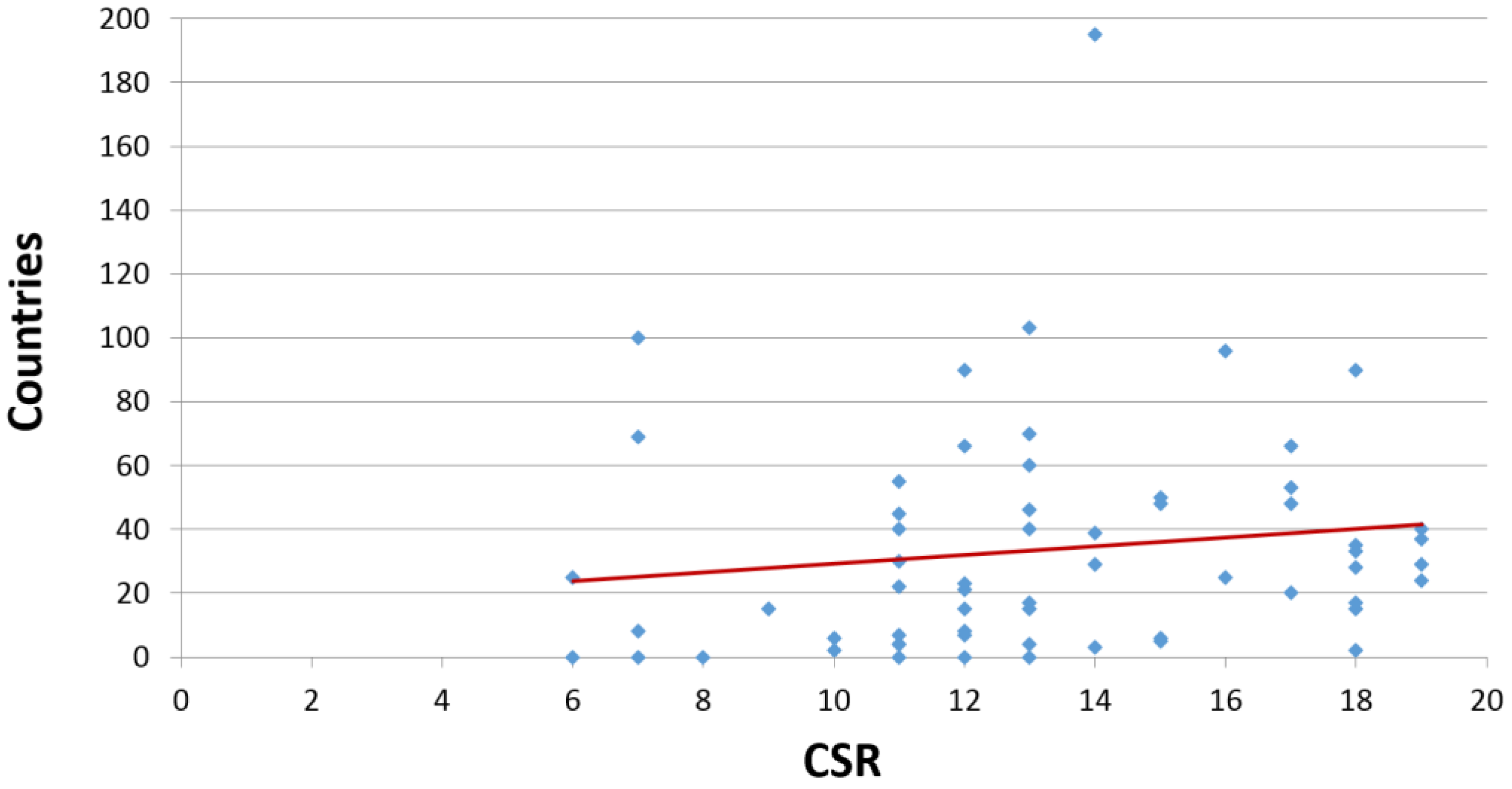

| 1. CSR | 13.23 | 3.57 | 1 | |||||

| 2. FSTS | 0.62 | 0.27 | 0.09 | 1 | ||||

| 3. FATA | 0.44 | 0.34 | 0.38 * | 0.52 ** | 1 | |||

| 4. COUNTRIES | 33.61 | 34.91 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.02 | 1 | ||

| 5. EXPORT_ACT | 90.16 | 0.35 ** | 0.30 * | 0.34 * | 0.32 * | 1 |

| Panel A: Internationalisation as % Sales (FSTS) | |||||||

| Variables | High Internationalisation | Low Internationalisation | Mann-Whitney U | ||||

| Mean | Median | AR a | Mean | Median | AR a | ||

| CSR N = 21, N = 24 | 13.76 | 15 | 26.00 | 12.29 | 12 | 20.38 | 189.00 |

| Panel B: Internationalisation as % Assets (FATA) | |||||||

| CSR N = 21, N = 24 | 14.05 | 14 | 26.71 | 12.04 | 12 | 19.75 | 174.00† |

| Panel A: Internationalisation as Number of Countries (COUNTRIES) | |||||||

| Variables | High Internationalisation | Low Internationalisation | Mann-Whitney U | ||||

| Mean | Median | AR a | Mean | Median | AR a | ||

| CSR N = 29, N = 32 | 14.31 | 14 | 36.62 | 12.25 | 12 | 25.91 | 301.00 * |

| Panel B: Internationalisation as Export Activity (EXP_ACT) | |||||||

| CSR N = 55, N = 6 | 13.64 | 13.60 | 32.86 | 9.50 | 9.50 | 13.92 | 62.50 * |

| Panel A: Internationalisation as % Assets (FATA) | |||||||

| Variables | High Internationalisation | Low Internationalisation | Mann-Whitney U | ||||

| Mean | Median | AR a | Mean | Median | AR a | ||

| Employees N = 21, N = 24 | 4.90 | 5 | 25.71 | 4.25 | 5 | 20.63 | 195.00 |

| Shareholders N = 21, N = 24 | 3.90 | 4 | 27.10 | 3.21 | 3 | 19.42 | 166.00 * |

| Panel B: Internationalisation as Number of Countries (COUNTRIES) | |||||||

| Employees N = 29, N = 32 | 4.86 | 5 | 35.71 | 4.25 | 5 | 26.73 | 327.50 * |

| Shareholders N = 29, N = 32 | 3.76 | 4 | 33.52 | 3.41 | 3 | 28.72 | 391.00 |

| Panel C: Internationalisation as Export Activity (EXP_ACT) | |||||||

| Employees N = 55, N = 6 | 4.65 | 5 | 32.31 | 3.50 | 3.50 | 19.00 | 93.00 † |

| Shareholders N = 55, N = 6 | 3.60 | 3 | 31.28 | 3.33 | 3.50 | 28.42 | 149.50 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Godos-Díez, J.-L.; Cabeza-García, L.; Fernández-González, C. Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Internationalisation Strategies: A Descriptive Study in the Spanish Context. Adm. Sci. 2018, 8, 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci8040057

Godos-Díez J-L, Cabeza-García L, Fernández-González C. Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Internationalisation Strategies: A Descriptive Study in the Spanish Context. Administrative Sciences. 2018; 8(4):57. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci8040057

Chicago/Turabian StyleGodos-Díez, José-Luis, Laura Cabeza-García, and Cristina Fernández-González. 2018. "Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Internationalisation Strategies: A Descriptive Study in the Spanish Context" Administrative Sciences 8, no. 4: 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci8040057

APA StyleGodos-Díez, J.-L., Cabeza-García, L., & Fernández-González, C. (2018). Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Internationalisation Strategies: A Descriptive Study in the Spanish Context. Administrative Sciences, 8(4), 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci8040057