Managing Your Brand for Employees: Understanding the Role of Organizational Processes in Cultivating Employee Brand Equity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Review of Literature

2.1. Services Branding and Brand Equity

2.2. Employee Based Brand Equity

2.3. Employee Based Brand Equity Process

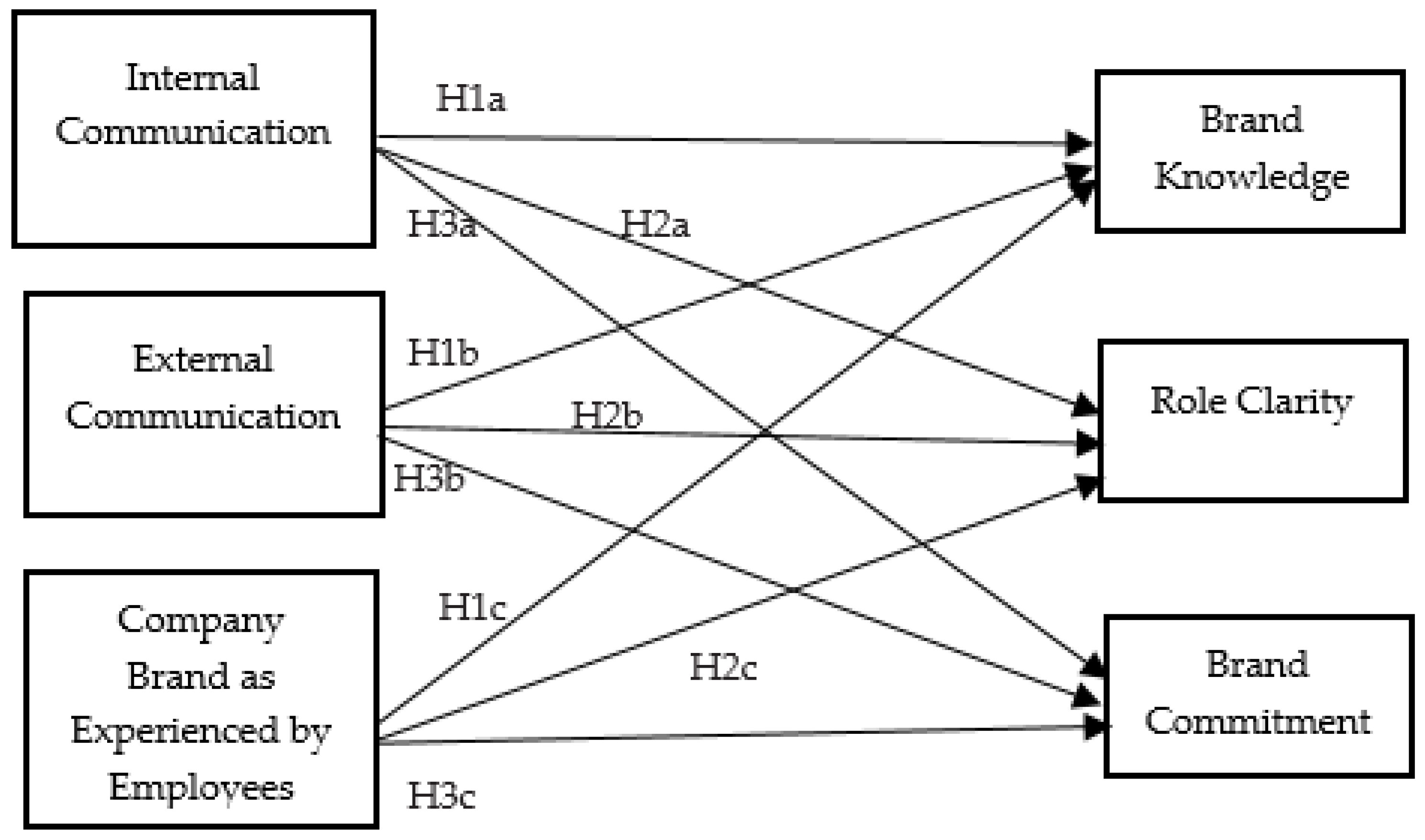

- H1a: Internal communication positively affects brand knowledge.

- H2a: Internal communication positively affects role clarity.

- H3a: Internal communication positively affects brand commitment.

- H1b: External communication positively affects brand knowledge.

- H2b: External communication positively affects role clarity.

- H3b: External communication positively affects brand commitment.

- H1c: Company brand as experienced by employees positively affects brand knowledge.

- H2c: Company brand as experienced by employees positively affects role clarity.

- H3c: Company brand as experienced by employees positively affects brand commitment.

3. Methods

3.1. Instrument and Measures

3.2. Sampling

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Profile of Respondents

4.2. Measurement and Structural Model

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Discussion of the Findings

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

5.3. Practical Implications

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aaker, David A. 1991. Managing Brand Equity. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ambler, Tim. 2003. Marketing and the Bottom Line: The Marketing Metrics to Pump up Cash Flow. London: Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, James C., and David W. Gerbing. 1988. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin 103: 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, Blake E., and Fred Mael. 1989. Social identity theory and the organization. Academy of Management Review 14: 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atilgan, Eda, Şafak Aksoy, and Serkan Akinci. 2005. Determinants of the brand equity: A verification approach in the beverage industry in Turkey. Marketing Intelligence amd Planning 23: 237–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurand, Timothy W., Linda Gorchels, and Terrence R. Bishop. 2005. Human resource management’s role in internal branding: An opportunity for cross-functional brand message synergy. Journal of Product & Brand Management 14: 163–69. [Google Scholar]

- Backhaus, Kristin, and Surinder Tikoo. 2004. Conceptualizing and researching employer branding. Career Development International 9: 501–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Thomas L., Adam Rapp, Tracy Meyer, and Ryan Mullins. 2014. The role of brand communications on front line service employee beliefs, behaviors, and performance. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 42: 642–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, Harvir S., and Peter A. Voyer. 2000. Word-of-mouth processes within a services purchase decision context. Journal of Service Research 3: 166–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstrom, Alan, Dannielle Blumenthal, and Scott Crothers. 2002. Why internal branding matters: The case of Saab. Corporate Reputation Review 5: 133–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, Leonard L. 2000. Cultivating service brand equity. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 28: 128–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, Roderick J., James R. M. Whittome, and Gregory J. Brush. 2009. Investigating the service brand: A customer value perspective. Journal of Business Research 62: 345–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmann, Christoph, and Sabrina Zeplin. 2005. Building brand commitment: A behavioral approach to internal brand management. Journal of Brand Management 12: 279–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmann, Christoph, Sabrina Zeplin, and Nicola Riley. 2009. Key determinants of internal brand management success: An exploratory empirical analysis. Journal of Brand Management 16: 264–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, Arjun. 1995. Brand equity or double jeopardy? Journal of Product & Brand Management 4: 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- De Chernatony, Leslie, and Susan Cottam. 2006. Internal brand factors driving successful financial services brands. European Journal of Marketing 40: 611–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Chernatony, Leslie, and Susan Segal-Horn. 2001. Building on services’ characteristics to develop successful services brands. Journal of Marketing Management 17: 645–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Chernatony, Leslie, Susan Drury, and Susan Segal-Horn. 2003. Building a services brand: Stages, people and orientations. Service Industries Journal 23: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Chernatony, Leslie, Susan Cottam, and Susan Segal-Horn. 2006. Communicating services brands’ values internally and externally. The Service Industries Journal 26: 819–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, William R., and Leonard L. Berry. 1981. Guidelines for the advertising of services. Business Horizons 24: 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, Rob. 2011. Using storytelling to maintain employee loyalty during change. International Journal of Business and Social Science 2: 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Gronroos, Christian. 2007. Service Management and Marketing: Customer Management in Service Competition. Chichester: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Hoogervorst, Jan, Henk van der Flier, and Paul Koopman. 2004. Implicit communication in organizations: The impact of culture, structure and management practices on employee behavior. Journal of Managerial Psychology 19: 288–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, Daire, Joseph Coughlan, and Michael Mullen. 2008. Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. The Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods 6: 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hur, Yoonkyung, and Howard Adler. 2011. Employees’ perceptions of restaurant brand image. Journal of Foodservice Business Research 14: 334–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, Rick. 2003. Turn employees into brand ambassadors. ABA Bank Marketing 35: 22. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, Kevin Lane. 1993. Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. The Journal of Marketing, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, Kevin Lane. 1998. Strategic Brand Management. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, Kevin Lane. 2003. Brand synthesis: The multidimensionality of brand knowledge. Journal of Consumer Research 29: 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Hong-Bumm, Woo Gon Kim, and Jeong A. An. 2003. The effect of consumer-based brand equity on firms’ financial performance. Journal of Consumer Marketing 20: 335–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimpakorn, Narumon, and Gerard Tocquer. 2009. Employees’ commitment to brands in the service sector: Luxury hotel chains in Thailand. Journal of Brand Management 16: 532–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Ceridwyn, and Debra Grace. 2005. Exploring the role of employees in the delivery of the brand: A case study approach. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal 8: 277–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Ceridwyn, and Debra Grace. 2008. Internal branding: Exploring the employee’s perspective. Journal of Brand Management 15: 358–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Ceridwyn, and Debra Grace. 2009. Employee based brand equity: A third perspective. Services Marketing Quarterly 30: 122–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Ceridwyn, and Debra Grace. 2010. Building and measuring employee-based brand equity. European Journal of Marketing 44: 938–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Ceridwyn, Debra Grace, and Daniel C. Funk. 2012. Employee brand equity: Scale development and validation. Journal of Brand Management 19: 268–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, Philip. 2003. Marketing Management. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Lencioni, Patrick M. 2002. Make your values mean something. Harvard Business Review 80: 113–17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lings, Ian, Amanda Beatson, and Siegfried Gudergan. 2008. The impact of implicit and explicit communications on frontline service delivery staff. The Service Industries Journal 28: 1431–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangold, W. Glynn, and Sandra Jeanquart Miles. 2007. The employee brand: Is yours an all-star? Business Horizons 50: 423–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, Sandra Jeanquart, and Glynn Mangold. 2004. A conceptualization of the employee branding process. Journal of Relationship Marketing 3: 65–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, Colin. 2002. Selling the brand inside. Harvard Business Review 80: 99–101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, Avinandan, and Neeru Malhotra. 2006. Does role clarity explain employee-perceived service quality? A study of antecedents and consequences in call centers. International Journal of Service Industry Management 17: 444–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piehler, Rico, Stephan Hanisch, and Christoph Burmann. 2015. Internal branding—Relevance, management and challenges. Marketing Review St. Gallen 32: 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punjaisri, Khanyapuss, and Alan Wilson. 2007. The role of internal branding in the delivery of employee brand promise. Journal of Brand Management 15: 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punjaisri, Khanyapuss, and Alan Wilson. 2011. Internal branding process: Key mechanisms, outcomes and moderating factors. European Journal of Marketing 45: 1521–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punjaisri, Khanyapuss, Heiner Evanschitzky, and Alan Wilson. 2009. Internal branding: An enabler of employees’ brand-supporting behaviors. Journal of Service Management 20: 209–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokeach, Milton. 1973. The Nature of Human Values. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Satorra, Albert, and Peter M. Bentler. 2001. A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika 66: 507–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalsvik, Hugo, and Bjørn Olsen. 2014. Service branding: Suggesting an interactive model of service brand development. Kybernetes 43: 1209–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, Kevin, and Ceridwyn King. 2010. When experience matters: Building and measuring hotel brand equity: The customers’ perspective. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 22: 589–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, Michael. 1973. Job market signaling. Uncertainty in Economics, 281–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, Henri, and John C. Turner. 1986. The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behaviour. u: Worchel S. i Austin WG (ur.) Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Chicago: Nelson Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, Kevin, Leslie de Chernatony, Lorrie Arganbright, and Sajid Khan. 1999. The buy-in benchmark: How staff understanding and commitment impact brand and business performance. Journal of Marketing Management 15: 819–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosti, Donald T., and Rodger D. Stotz. 2001. Brand: Building your brand from the inside out. Marketing Management 10: 28. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, Henry, Catherine Cheung, and Ada Lo. 2010. An exploratory study of the relationship between customer-based casino brand equity and firm performance. International Journal of Hospitality Management 29: 754–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, Mary, and Paul R. Jackson. 2007. Rethinking internal communication: A stakeholder approach. Corporate Communications: An International Journal 12: 177–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Lina, Ceridwyn King, and Rico Piehler. 2013. That’s not my job: Exploring the employee perspective in the development of brand ambassadors. International Journal of Hospitality Management 35: 348–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Jen-Te, Chin-Sheng Wan, and Chi-Wei Wu. 2015. Effect of internal branding on employee brand commitment and behavior in hospitality. Tourism and Hospitality Research 15: 267–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, Valarie, and Mary Jo Bitner. 1996. Services Marketing. New York: McGraw Hill. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 226 | 60.4 |

| Female | 148 | 39.6 | |

| Total | 374 | 100 | |

| Age | 18–25 | 147 | 39.3 |

| 26–35 | 129 | 34.5 | |

| 36–45 | 78 | 20.9 | |

| 46 or above | 20 | 5.3 | |

| Total | 374 | 100 | |

| Marital Status | Single | 216 | 57.8 |

| Married | 158 | 42.2 | |

| Total | 374 | 100 | |

| Education Level | High School | 132 | 35.3 |

| Pre-College | 47 | 12.6 | |

| Bachelor | 167 | 44.7 | |

| Graduate | 28 | 7.4 | |

| Total | 374 | 100 |

| Cross-Construct Correlations | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement Scale | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Internal communication | 1.00 | 0.428 | 0.384 | 0.219 | 0.475 | 0.126 |

| External communication | 1.00 | 0.546 | 0.489 | 0.248 | 0.401 | |

| Brand as experienced by employees | 1.00 | 0.236 | 0.274 | 0.265 | ||

| Role clarity | 1.00 | 0.541 | ||||

| Brand Commitment | 1.00 | |||||

| Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | 0.53 | 0.58 | 0.45 | 0.67 | 0.59 | 0.55 |

| Construct | Mean | SD | AVE | Composite Reliability | Standardized Factor Loadings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Communication | 0.53 | 0.82 | |||

| IC1 | 3.7080 | 0.9130 | 0.723 | ||

| IC2 | 3.6903 | 0.8246 | 0.638 | ||

| IC3 | 3.5487 | 0.8659 | 0.720 | ||

| IC4 | 3.0531 | 0.8539 | 0.678 | ||

| External Communication | 0.58 | 0.90 | |||

| EC1 | 3.8230 | 1.0956 | 0.739 | ||

| EC2 | 3.8142 | 1.0982 | 0.738 | ||

| EC3 | 3.5310 | 1.0109 | 0.707 | ||

| EC4 | 3.8407 | 1.0737 | 0.764 | ||

| EC5 | 3.8053 | 1.1008 | 0.672 | ||

| EC6 | 2.6903 | 0.6557 | 0.716 | ||

| EC7 | 2.7168 | 0.6334 | 0.629 | ||

| EC8 | 3.6195 | 0.6473 | 0.652 | ||

| EC9 | 2.7699 | 0.6815 | 0.669 | ||

| EC10 | 3.6018 | 0.8918 | 0.653 | ||

| Brand as Experienced by Employees | 0.45 | 0.89 | |||

| BE1 | 4.5752 | 0.4965 | 0.708 | ||

| BE2 | 4.5310 | 0.5012 | 0.621 | ||

| BE3 | 4.5575 | 0.4988 | 0.682 | ||

| BE4 | 4.5398 | 0.5006 | 0.649 | ||

| BE5 | 4.5221 | 0.5017 | 0.657 | ||

| BE6 | 4.0442 | 0.7949 | 0.586 | ||

| BE7 | 3.9292 | 0.7643 | 0.530 | ||

| BE8 | 3.1593 | 0.8608 | 0.585 | ||

| BE9 | 4.0088 | 0.8072 | 0.579 | ||

| BE10 | 4.4159 | 0.4950 | 0.647 | ||

| BE11 | 3.1416 | 0.4934 | 0.564 | ||

| BE12 | 4.5310 | 0.5012 | 0.606 | ||

| BE13 | 4.3178 | 0.7548 | 0.649 | ||

| BE14 | 4.4071 | 0.4934 | 0.576 | ||

| Brand Knowledge | 0.67 | 0.93 | |||

| BK1 | 3.1327 | 0.8399 | 0.548 | ||

| BK2 | 3.3009 | 0.7056 | 0.972 | ||

| BK3 | 3.3363 | 0.7147 | 0.764 | ||

| BK4 | 3.3540 | 0.6670 | 0.648 | ||

| BK5 | 3.3451 | 0.7412 | 0.767 | ||

| BK6 | 3.2478 | 0.7137 | 0.802 | ||

| BK7 | 3.2743 | 0.7588 | 0.917 | ||

| Role Clarity | 0.59 | 0.92 | |||

| RC1 | 4.4867 | 0.5020 | 0.800 | ||

| RC2 | 4.6549 | 0.4775 | 0.795 | ||

| RC3 | 4.4248 | 0.4965 | 0.771 | ||

| RC4 | 4.5929 | 0.4934 | 0.759 | ||

| RC5 | 4.4779 | 0.5017 | 0.768 | ||

| RC6 | 3.4425 | 0.4988 | 0.788 | ||

| RC7 | 3.5664 | 0.4977 | 0.753 | ||

| RC8 | 3.5221 | 0.5017 | 0.764 | ||

| Brand Commitment | 0.55 | 0.86 | |||

| BC1 | 3.5664 | 0.4977 | 0.753 | ||

| BC2 | 4.4956 | 0.4625 | 0.750 | ||

| BC3 | 4.4690 | 0.5012 | 0.763 | ||

| BC4 | 4.5044 | 0.5356 | 0.657 | ||

| BC5 | 4.4810 | 0.5012 | 0.720 |

| Path to | Path from | H0 | Std. Coeff. | t-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brand Knowledge | Internal Communication | H1a: Supported | 0.839 | 7.484 ** |

| Role Clarity | H2a: Supported | 0.799 | 8.363 ** | |

| Brand Commitment | H3a: Not Supported | 0.054 | 1.854 | |

| Brand Knowledge | External Communication | H1b: Not Supported | 0.098 | 1.281 |

| Role Clarity | H2b: Not Supported | 0.122 | 1.734 | |

| Brand Commitment | H3b: Supported | 0.379 | 4.145 ** | |

| Brand Knowledge | Brand as Experienced by Employees | H1c: Not Supported | 0.106 | 1.386 |

| Role Clarity | H2c: Not Supported | 0.086 | 1.295 | |

| Brand Commitment | H3c: Supported | 0.629 | 8.256 ** |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Erkmen, E. Managing Your Brand for Employees: Understanding the Role of Organizational Processes in Cultivating Employee Brand Equity. Adm. Sci. 2018, 8, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci8030052

Erkmen E. Managing Your Brand for Employees: Understanding the Role of Organizational Processes in Cultivating Employee Brand Equity. Administrative Sciences. 2018; 8(3):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci8030052

Chicago/Turabian StyleErkmen, Ezgi. 2018. "Managing Your Brand for Employees: Understanding the Role of Organizational Processes in Cultivating Employee Brand Equity" Administrative Sciences 8, no. 3: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci8030052

APA StyleErkmen, E. (2018). Managing Your Brand for Employees: Understanding the Role of Organizational Processes in Cultivating Employee Brand Equity. Administrative Sciences, 8(3), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci8030052