Abstract

This paper evaluates current payment schemes employed by the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps) in the Philippines using six assessment criteria: transaction cost, security/risks, speed and timeliness, acceptability, resilience and flexibility. Employing data collected at the regional level, we establish four main findings: (1) all 4Ps payment conduits present trade-offs; (2) a payment approach that uses mainstream financial infrastructure is beneficial if cost, speed and simplicity of the payment system are critical; (3) competition for 4Ps contracts for Payment Service Providers (PSPs) has improved the quality of payment services and minimized costs; and (4) the efficiency of the program is greatly influenced by the commitment of the PSP to deliver the cash benefits to the recipients in a timely manner rather than by maximizing conduit branches.

1. Introduction

Cash transfers are a form of social assistance, delivered to secure various developmental, humanitarian or emergency objectives. These kinds of transfers are emerging in many developing countries as potentially effective social interventions or protection initiatives for tackling poverty. Cash transfers are critical to alleviating poverty because they reinforce inclusive growth by providing resources to the most vulnerable groups in a society. While cash transfers can either be conditional or unconditional, conditional cash transfers (CCTs) have become increasingly popular since they transfer money to poor households conditional upon actively fulfilling stipulated commitments in education, health, nutrition and the like. Empirical evidence from the evaluation of existing social transfers in developing countries suggests that they can help tackle hunger, poverty, educational depravation and the health of poor families, promote gender equality and contribute to empowering people [1,2,3]. Consequently, even if cash transfers are not a universal panacea, they will continue to perform an important role in a social policy context.

While there is extensive literature on the impact of cash transfer programs in various operational respects, little attention has focused on program design, specifically on the evaluation of the different payment mechanisms used by cash transfer programs [4]. Moreover, program operators seldom enjoy choice between different mechanisms [5]. Political and other pressures usually imply that program operators have limited opportunities to assess alternative options except in terms of their relative costs and feasibility [6].

An important aspect of the design of a CCT program is the delivery of payments and evaluating the efficacy of current and alternative distribution mechanisms. An effective payment system implies low transaction costs incurred by the program and minimal opportunity costs borne by beneficiaries. Inefficiencies in payment mechanisms may diminish the net value obtained by the recipients.

In the Philippines, the payment mechanism of the cash transfer program—locally known as Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps)—uses account-linked cards provided by the Land Bank of the Philippines (LBP). The LBP serves as the disbursing institution of the 4Ps [7]. It is responsible for managing payments and reporting to the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD)—the primary Philippine government agency mandated to develop, implement and coordinate social protection and poverty-reduction solutions for poor people.

However, as a result of the expansion of the coverage of the program within its first year of operation, there was a need for more effective and efficient payment mechanisms. This is primarily because of the limited capacity of LBP to pay recipients in remote areas. Accordingly, LBP was only kept as sole conduit for two years and other methods were then introduced. Some of the pressing challenges surrounding the payment mechanism of the 4Ps include: (1) accuracy; (2) timeliness; (3) remoteness; and (4) an absence of banking institutions [8]. Currently, in addition to the service provided by LBP, payment services are also supplied by rural banks, postal services and private lending and telephone companies.

The present paper seeks to build on work by Harvey [9], Devereux and Vincent [10], and Murray and Hove [11]. In particular, this study seeks to answer the following research questions: (a) how best to assess the choices between different cash delivery options; (b) how to establish if operating constraints restrict the choice of available payment mechanisms; and (c) whether or not to consider recipients in the design stage of programs. These research questions are consistent with Harvey [9] who indicated the need for further attention to these aspects with regards to choosing appropriate cash delivery options. Similarly, Murray and Hove [11] stressed that the operating environment and program design play a significant role in the cost-efficiency of humanitarian programs. However, in this paper, we will not select a particular payment scheme since this would require much more data as well as the involvement of different stakeholders.

Given the scope and complexity of the program implementation, it is imperative to have an understanding of the efficacy and effectiveness associated with the different payment schemes. Accordingly, in this paper we conduct an evaluation of the various payment mechanisms of the 4Ps. More specifically, our paper aims to:

- (a)

- Assess the strengths and weaknesses of the different cash transfer schemes of 4Ps.

- (b)

- Estimate the differences in cost and time required to deliver cash assistance through the different 4Ps payment schemes.

- (c)

- Assess if a competitive procurement process (by way of bidding) of engaging Payment Service Providers (PSPs) is effective in securing the lowest price with the best service.

- (d)

- Identify indicators of outcome and cost efficiency for different payment schemes.

The remainder of the paper is divided into five main parts. Section 2 provides a brief description of the institutional background underlying the 4Ps and its payment system. Section 3 offers a review of the scholarly literature on payment systems of cash transfer programs and the evaluation of these payment systems. The methods of analysis used in the evaluation of the various 4Ps payment schemes are outlined in Section 4. The findings of the paper are presented in Section 5. The paper ends with some brief concluding comments in Section 6.

2. Institutional Background

An overview of the cash transfer program in the Philippines, its design and the different payment mechanisms adopted by the program are presented below by way of institutional background as to how the program is designed, what its objectives are and how the delivery of cash transfers are implemented.

2.1. Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps)

The 4Ps is closely patterned on successful CCTs in Latin America, which seek improvement in social assistance and social development, both of which are central to the Philippine government’s poverty reduction and social protection strategy. To boost its prime focus of building human capital, the 4Ps provides short-term income support to extremely poor eligible households, contingent on their compliance with its conditions, such as enrolment in school (children 6–14 years old) and regular visits to health centers (by pregnant women and children 0–5 years old). A household can be an eligible recipient of 4Ps provided the following criteria are met: (a) resident in program areas of the 4Ps; (b) the household is identified as poor based on a proxy means test (PMT); and (c) the household should include at least one child below 15 years old at the time of enrolment in the program or it should include a pregnant woman. The maximum benefit per household is Php 1400.00 (around US$29.33). The amount paid is subject to the number of conditions being met and the number of children in question. Payment is bi-monthly and the timing of payments depends on the approved annual timeline, but is usually the last week of each month.

The 4Ps began as a pilot program of the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) in 2007 [7] and it was launched as a full-scale cash transfer program in 2008. As of August 2013, there were about four million recipients in all 17 regions of the Philippines, covering 79 provinces, 143 cities, 1484 municipalities and 40,978 barangays (also known as barrio which is the smallest administrative division in the Philippines and it is the native Filipino term for a district, ward or village) [5]. LBP has acted as the sole disbursing bank of the program.

2.2. 4Ps Payment System

At the start of the program, LBP remained the sole conduit for two years and cash grants were disbursed either through offsite payments or through LBP cash cards. Where offsite payments are made, the process is coordinated by the Municipal Social Welfare and Development Office (MSWDO) and municipal links and payments are done on a specific day and at a specific venue. Municipal links are casual DSWD workers to help in the implementation of 4Ps in a respective municipality. They are being assisted by the LGU link, which serves as the local counterpart of the LGU, as support services and manpower at the municipality level. In cases where some of the program recipients live in remote places, they had to travel to the specified venue thereby incurring transportation costs. The LBP’s main thrust is to disburse the cash payments to the beneficiaries in a timely and safe manner, regardless of program’s guidelines, which require that the cost of travel should be no more than Php100 (US$ 2.25). However, conducting an offsite payment is cumbersome to the LBP since the payment schedule has to be done either on weekends or on holidays, compelling bank employees to render overtime. Moreover, security risk is high for offsite payments when moving substantial amount of cash to remote areas, more often plagued with lawlessness.

By contrast, recipients who were given cash cards could withdraw their payments with some flexibility in the timing of payouts from any LBP automated teller machine (ATM), free of charge, or at any Bancnet/Megalink/Expressnet ATM, where the program covers up to Php20 (US$ 0.41) of the transaction fee. However, program recipients were required to travel to town centers where the nearest LBP ATM or other ATMs are located to withdraw the cash transfer.

The unexpected expansion of the program within its first year of implementation placed the LBP in difficulties, struggling to complete timely and accurate payments to all recipients in every two-month period. As a consequence, the LBP started engaging other payment conduits that can better service recipients in remote areas, where LBP facilities are not available. Additional payment service providers were evaluated, accredited and engaged in order to meet the program’s guidelines of timely and accessible payment facilities so that recipients were not required to spend Php100 (US$ 2.25) on transportation simply to collect their benefits with the flexibility in the timing of payouts. The additional service providers are PhilPost, Rural banks, cooperative banks, MLhuillier agents and GCash.

PhilPost is a publically owned and controlled corporation responsible for providing postal services in the Philippines. As a payment conduit, PhilPost serves in a temporary intermediary role in the more accessible municipalities by making payments to recipients who have not received their LBP cash cards. A good reason for choosing PhilPost as a conduit lies in the fact that it offers an existing network of post offices to deliver cash payments to recipients. GCash is the Globe’s mobile money service where it uses its mobile money platform as a mechanism in making payments to 4Ps beneficiaries. MLhuillier is a private financial services agent that leverages its branch networks to pay recipients, while rural banks are government-sponsored/assisted entities which are privately managed and largely privately owned. They provide credit facilities to farmers, merchants, cooperatives, and to people in rural communities. As a conduit, rural banks are provided with a line of credit by LBP every payout period. These providers all disbursed payments to recipients either over the counter (OTC) or manually.

3. Perspectives on Cash Transfer Program Efficacy

Several studies have been conducted to evaluate the efficacy and effectiveness of cash transfer programs. The focus of these studies encompasses different aspects such as the design and the relative costs of program delivery and the efficiency of delivery and implementations. In an analogous manner, there are also studies that have been conducted to assess the different payment mechanisms in terms of their advantages and disadvantages.

When planning, designing and implementing a payment system for cash transfer program, the main goal of the payment system is typically “to successfully distribute the correct amount of benefits to the right people at the right time and frequency while minimising costs to both the program and the beneficiary” [12]. According to Beswick [13], it is also important to understand the varying motivations of all stakeholders.

3.1. Payment System of Cash Transfer Program

Generally, most cash transfer programs employ various payment systems, including “cash-in-envelope”, voucher-based, pre-paid ATM cash cards, and mobile money transfer products. The most important aspect in the choice of the payment system is the consideration of the significant security risks that the payment methods pose, not only to the beneficiaries, but also to the payment staff as well. Forcier [14] emphasized that distribution can be difficult in regions with limited institutional capacity, lacking adequate financial structure, with frequent conflict and endemic corruption. The most preferred option is thus to make use of an existing financial system which can provide the requisite infrastructure. In recent years, distribution systems have greatly improved, especially with the use of bank debit cards. However, Nigenda and Gonzalez-Robledo [15] observed that even with the improvement in distribution systems, a problem still looms for beneficiaries living in far-flung areas, since they still need to incur additional expenses to go to towns to access benefits. By contrast, other systems, like distributing the money through community channels, can make transfers accessible, but nonetheless entail risks.

In identifying appropriate alternative delivery mechanisms for the cash transfers, Langhan et al. [16] argue that the critical success factor of a cash transfer program is the development and deployment of a reliable, auditable and cost effective disbursement and payment system which can deliver regular cash transfers. Even with the continued efforts of improving the cash transfer distribution systems, there are still potential shortcomings which must be addressed, such as accessibility and its attendant security risk.

Combinations of different delivery methods and delivery agents have often been used in various countries. Table 1 presents selected cash delivery options used by different cash transfer programs in various countries:

Table 1.

Selected cash delivery options.

| Delivery Agent | Delivery Method | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cash or Voucher | E-wallet | Bank Account | ||||||

| Direct (cash in envelopes or voucher) | Check or bank draft | Mobile phone | Smart card | Prepaid card | Debit card | Mobile phone | Smart card | |

| Aid Agency directly | Save the Children in Myanmar (Burma) | WFP (World Food Program in Syria) | Concern, Oxfam in Kenya | |||||

| Government | Kenya Hunger Safety Net (HSNP) | Indian and Pakistani governments | Kenya HSNP | |||||

| Bank | DRC in Chechnya | Red Cross in Indonesia | Concern in Malawi | |||||

| Post Office | Save the Children in Pakistan | Save the Children in Swaziland | Mercy Corps in Pakistan | |||||

| Micro-Finance institution | Action Aid in Myanmar (Burma) | |||||||

| Remittance company | Horn Relief in Somalia | |||||||

| Security company | WV in Lesotho | |||||||

| Local traders | Save the Children in Niger | Kenya HSNP | DRC ex-soldiers | |||||

Note: Source: Harvey [9].

3.2. Evaluation of Payment System of Cash Transfer Program

O’Brien [17] offered a guide to calculating the cost of delivering cash transfers in humanitarian emergencies using case studies in Kenya and Somalia. His guidelines focused on the following: (1) type of costing analysis to be undertaken; (2) dimensions of cash-transfer costing; and (3) common measures of cost-efficiency. Langhan et al. [16] studied the identification of appropriate alternative delivery mechanisms for the cash transfers in Malawi, but their study only focused on the advantages and disadvantages of the various payment mechanisms adopted.

Carrillo and Jarrin [18] examined the efficiency of the delivery of cash transfers to the poor and improving the design of a conditional cash transfer program in Ecuador. Using the Maximum Likelihood method, they specified and estimated the most basic version of a behavioral dynamic model that depicts the individual’s decision to collect the transfer. Considering the costs (i.e., transportation, opportunity and related costs) involved, they invoked two assumptions: (a) that rational beneficiaries choose between collecting the transfer in the current period or waiting to redeem the accumulated subsidy in the next period; and (b) households which are located closer to payment agencies or those that experience lower opportunity costs have stronger incentives to redeem transfers more often. They showed that—despite the simplicity of their behavioral model—it could nonetheless be a powerful tool for designing the delivery of payments for a CCT program.

Bold et al. [19] presented evidence gained from a comprehensive study of four different countries implementing cash transfer programs by comparing different payment approaches and assessing which were financially inclusive. They focused on the experience of governments, recipients and service providers and much of their assessment is descriptive. In an analogous vein, Zimmerman et al. [20] came up with a comparative analysis of program design and implementation on e-payment schemes linked to financial inclusion in four different countries adopting cash transfer programs. They focused on the development and evolution of programs, current delivery and payment processes, the costs and benefits to program providers of using e-payments, and the experience of e-payment recipients and staff at the field level.

O’Brien et al. [21] investigated the costs of using electronic payment mechanisms for emergency cash transfers. Focus fell on the cost-efficiency analysis of the payment mechanisms by comparing electronic transfers versus the traditional manual cash delivery method of seven emergency cash transfer programs. Similarly, Murray and Hove [11] compared three different cash transfer mechanisms used in one humanitarian program in the Democratic Republic of Congo and specifically looked into the differences in cost and time required to deliver cash assistance using three different payment mechanisms. Harvey [9] distilled lessons learned from experience and provided guidance for project managers of cash transfer programs to make choices about how best to deliver cash to people. Similarly, Barca [4] considered the best ways to transfer cash in cash transfers. Their study presents qualitative and quantitative evidence on three different payment systems being used in cash transfer programs in Kenya. Evaluation studies on ‘branchless banking’ mechanisms, like electronic delivery method or mobile money, were also conducted by Oberlander and Brossman [22], Chandy and Kharas [23] and Aker et al. [24].

It is also worth noting that evaluation studies on the payment mechanisms of the 4Ps have also been conducted. For example, Zimmerman and Bohling [5] and the Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP) [25] both focused on electronic payments. Gusto and Roque [26] examined two methods of dispensing cash grants to Indigenous People (IP) beneficiaries and how this select group of beneficiaries perceived money and financial technology.

Given this body of empirical work, which focuses on the overall theme of assessing different payment service providers (PSPs) in terms of various criteria, Table 2 outlines key criteria for assessing cash delivery options which serves as a basis for the framework of analysis in the present paper.

Table 2.

Key criteria for assessing cash delivery options.

| Criteria | Assessment questions |

|---|---|

| Objectives | What are the key objectives of the program? |

| Delivery options and existing infrastructure | What delivery options are available in the area (banks, postal service, mobile operators)? Is there mobile phone coverage? What are the motivations of potential providers (e.g., Financial gain, social mission, image-boosting)? |

| Cost | What are the costs of different options for the agency (provider charges, staff, transport security and training costs)? What are the costs for the recipient (charges, travel costs, waiting time)? |

| Security | What are the security risks associated with each delivery option for the agency and the recipients? |

| Controls/risks | What are the key risks that need to be managed? What corruption risks are associated with each delivery option? What fiscal controls and standards are in place? |

| Human Resources | How many staffs are required for each option? |

| Speed | How long is it likely to take to get each delivery option and running? What are the regulatory requirements for the recipients in respect of each option? |

| Resilience | How resilient are the potential options in the face of possible disruptions to communication and infrastructure following disaster? How reliable and stable are potential commercial providers? |

| Scale | What is the target population, how large are the payments and how frequently will they be made? How will each delivery mechanism be likely to cope? |

| Flexibility | How flexibly can the different options adjust the timing and amount of payments? |

Note: Source: Harvey [9].

4. Empirical Strategy

4.1. Analytical Framework

In assessing the payment system of 4Ps, we employ a series of program-level criteria drawn by Harvey [9]. We invoke the following criteria as the basis for comparative analysis of the various payment mechanisms and to justify the choice and design of the payment system currently employed by 4Ps: suitability for program objectives, existing infrastructures and options, costs, resilience, flexibility and minimization of the risk of fraud and corruption. From these criteria, the different advantages and disadvantages of different cash delivery options are presented in Table 3, which also serve as benchmarks in comparing the different 4Ps payment mechanisms.

Table 3.

Advantages and disadvantages of different cash delivery options.

| Cash Delivery Option | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Direct delivery (cash in envelopes) | Speed, simplicity and cost Flexible if recipients move location. | Security and corruption risks. Often labor intensive, especially in terms of staff time. For recipients a lack of flexibility in when they receive cash and possible long waiting times |

| Delivery using bank accounts | Reduced workload for agency staff. Corruption and security risks may be reduced if institutions have strong control systems. Flexibility and convenience for recipients who can choose when to withdraw cash and avoid queues. Access to financial system for previously unbanked recipients | Time needed to negotiate roles, contractual terms and establish systems. Reluctance to set up accounts for small amounts of money. Bank charges may be expensive. Recipients may be unfamiliar with financial institutions and have some fears in dealing with them. Possible exclusion of people without necessary documentation and children. |

| Without accounts using checks | As above and can avoid delays that can be caused by having to verify transfers. | As bank accounts are not opened, recipients do not gain access to the banking system. |

| Delivery using sub-contracted parties (remittance companies) | Sub-contracted parties accept some responsibility for loss. Security risks for agency reduced. Remittance companies may have greater access than agencies to insecure areas. Recipients may be familiar with these types of systems. Flexibility and access—these systems may be near to where recipients live and may offer greater flexibility in receiving their cash. | The system may require greater monitoring for auditing purposes. Reduced control over distribution time frame. Credibility could be at risk if the transfer company cannot provide the money to the agreed time schedule. Recipients may be more removed from aid agency and so less able to complain if things go wrong. |

| Delivery via pre-paid cards or mobiles | As with banks, possible reduced corruption and security risks, reduced workload for agency staff, greater flexibility for recipients. Greater flexibility in where cash can be collected (e.g. Mobile Points of Sale, local traders). A mobile phone (individual or communal) can be provided at low cost to those who do not already have them. | Systems may take time and be complex to establish. Risks of agents or branches running out money. Costs and risks of new technology such as smart cards. Recipients may be unfamiliar with new systems. Form of identity required to use payment instrument depends on local regulations and may exclude some people. |

Source: Harvey [9].

4.2. Data and Study Area

We used secondary administrative data collected from the four provinces of Davao Region: Davao del Sur, Davao del Norte, Compostela Valley and Davao Oriental. The Davao region located on the southeastern portion of Mindanao is designated as Region XI and consists of five provinces namely: Compostela Valley, Davao del Norte, Davao del Sur, Davao Oriental and the newly created Davao Occidental. For this study, the LGUs in Davao Occidental are still part of Davao del Sur. Davao City is the regional capital and also the largest city on Mindanao. 4Ps data were collected on a per set basis covering all 49 cities/municipalities of Davao region. Since the implementation of the 4Ps was done on a per set basiswhereby gradual implementation of the program done by phase of expansion, where Set 1 covered beneficiaries of the program in the poorest of the 20 provinces; the second expansion (Set 2) covered beneficiaries living in municipalities with poverty incidence above 60% and the subsequent phases covering other identified eligible beneficiaries. Because of this nature of implementation the data obtained were the different payment service providers (PSP) of 4Ps from Set 1 to Set 6. The periods covered for the study varies for each set as follows: Set 1 (2008–2013); Set 2 (2009–2013); Set 3 (2009–2013); Set 4 (2011–2013); Set 5 (2012–2013); and Set 6 (2013). This is because the start of program implementation for each set also varied.

Most of the data, like different payment schemes, total households served per payment scheme per set per year, and transaction fees per conduit, were obtained from the finance department of the DSWD.

5. Results and Discussion

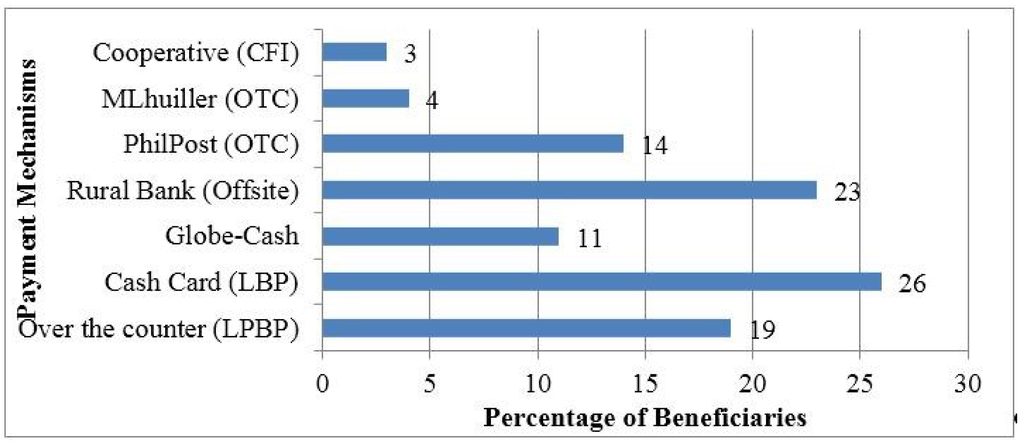

As shown in Figure 1, the breakdown per payment mechanism reveals that the highest percentage of beneficiaries served was through electronic payments for 26 % of the beneficiaries using the cash-card of the LBP. The combination of LBP’s over-the-counter (OTC) and cash cards (CC) mechanisms show a total of 45 % of beneficiaries served, which is expected, since LBP was the sole conduit for the first two years. Considering that some of the beneficiaries were located in areas where LBP’s ATM access fell outside of the 4Ps’ minimum distance for pay-points, other conduits/payment mechanisms were outsourced to deliver 4Ps payments. Rural banks ranked second in terms of the percentage of beneficiaries served, at 23 %, followed by PhilPost at 14 %. The cooperative bank and MLhuillier had the lowest percentage of beneficiaries served at three and four percent, respectively.

Figure 1.

Percentage of beneficiaries served per payment mechanism.

5.1. Comparison of Strengths and Weaknesses of Different Payment Schemes

A comparison of the current 4Ps payment schemes is illustrated in Table 4 showing various features of the program. Table 4 shows that for the first two years of 4Ps operation, only the LBP served as the sole PSP and manager of all 4Ps payments. This is consistent with what was stipulated by the Department of Finance that the DSWD should partner with only one PSP for 4Ps in order to simplify processes. Nonetheless, with the unforeseen scale-up of the program within the first year of implementation, the LBP was challenged to meet the payment demands of 4Ps on a bi-monthly schedule in an accurate and timely manner. Thus after two years, LBP engaged additional conduits, which could reach remote areas, beyond the capacity of LBP. In areas where there are no available ATMs, beneficiaries were assigned to collect payments from a rural bank, provided that these rural banks are situated within a Php100 (US$2.10) travel cost round trip for each beneficiary. In cases where the location of these rural banks did not meet program’s guidelines, 4Ps beneficiaries were assigned to other OTC conduits that schedule payouts in the nearest offsite areas and pay the beneficiaries over the counter or manually. These conduits include Globe G-cash, PhilPost and MLhuillier. Rural banks, cooperative association and PhilPost charged the same transaction fee per beneficiary; however, Globe G-cash charged the highest fee. Thus, after a year of being a conduit, Globe G-cash was replaced by MLhuillier since the latter offered a lower transaction fee for the same OTC service. This represents a consequence of vigorous competition to be 4Ps’ payment service provider contract by way of bidding.

Table 4.

Comparison of Current 4Ps Payment Mechanisms.

| LBP (OTC or offsite) | LBP (CC) | Globe G-Cash | Rural Bank (offsite) | Coop Bank (offsite) | PhilPost (OTC) | MLhuiller (OTC) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year PSP Started | 2008 | 2009 | 2011 | 2011 | 2012 | 2012 | 2013 |

| Transaction Fees* | Php24 (US$0.50) | Php24 (US$0.50); Inter branch transaction Php20 (US$0.42) | Php75 (US$ 1.57) | Php50 (US$ 1.05) | Php50 (US$ 1.05) | Php50 (US$ 1.05) | Php42 (US $0.88) |

| Pay Points | Designated venue (s) | Any LBP branch in region 11 (11 branches) or ATMs (58) | Offsite areas providing OTC payments | Offsite areas providing OTC payments | Offsite areas providing OTC payments | PhilPost locations in region 11 (50) | MLhuiller locations in region 11 (41) |

| Payment Instruments | OTC | Cash Cards | G-Cash 4Ps Payment Slips (similar to ARs) | AR Form | AR Form | AR Form | AR Form |

| Payment Device | OTC Teller | ATM | G-cash Agent | OTC Teller | OTC Teller | Post Office Teller | Offsite Agents |

| Authentication Process | ID card | PIN | ID card | ID card | ID card | ID card | ID card |

Notes: Source: DSWD Region XI. * Transaction fees—fees being charged by a conduit for each beneficiary per transaction. It is based on the amount proposed by the bidders for PSP contract.

Comparing the various payment mechanisms of 4Ps, all conduits contracted by LBP that deliver payments through direct delivery or cash in envelopes have the advantages of speed, simplicity and flexibility, but have to overcome trade-offs in terms of security and corruption risks (see Appendix A for a detailed assessment using the key criteria in Table 2). While these conduits offered the best alternative service to LBP’s payment scheme since they have greater access to insecure areas, they nevertheless charged a transaction fee that is 52% to 68% higher than the fee being charged by LBP to the program. PhilPost and MLhuillier locations are more frequent in the Davao region, with 50 and 41 branches, respectively.

By contrast, beneficiaries collecting the benefits through these modes of payment face a lack of flexibility in receiving the payments and the possibility of long queues compared with the LBP’s cash-card since the recipients can choose when to withdraw cash and avoid queues. In addition, the other advantages of these payment mechanisms to beneficiaries are accessibility and familiarity since these conduits may be close to where beneficiaries live. Moreover, they are familiar with these types of payment mechanisms (see Appendix B for the summary of the assessment based on the viewpoint of the recipients).

Most of the payment instruments are similar for the various payment mechanisms using the acknowledgement receipt (AR), except for the LBP’s cash-card. Similarly, for the authentication process, most of the payment mechanisms used an identification card, while a personal identification number (PIN) is used for the LBP cash-card.

5.2. Differences in Cost and Time Required to Deliver Cash Assistance and Competition of 4Ps Contracts to Deliver Cash Transfer

Table 5 sets out the percentage of transaction costs of delivering the cash benefits to beneficiaries on per payment scheme and a per province basis. Comparing the transaction costs for various payment schemes was done per province since the starting point of our analysis is the location and the numbers of LBP branches and ATMs for each province because these are the main considerations when LBP engages other payment conduits. Similarly, a yearly schedule of payment schemes engaged by the 4Ps for payment distribution was summarized on a per set, per municipality and per province basis in order to assess if the competitive procurement process of engaging PSPs is effective in getting the lowest price with the best service. A brief summary of this detailed report was added in Appendix C to complement this data with the size of the beneficiaries and the number of cities/municipalities served per payment scheme.

Table 5.

Percentage of transaction costs per payment scheme, per province (2008–2013).

| Province | LBP (OTC) | LBP (CC) | Globe G-Cash | Rural Bank | Cooperative | Phil. Postal | MLhuillier |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Davao Oriental | 8.95% | 9.33% | 7.01% | 74.26% | 0.00% | 0.40% | 0.05% |

| Davao del Norte | 6.93% | 20.37% | 2.66% | 53.30% | 0.01% | 15.19% | 1.53% |

| Davao del Sur | 11.97% | 24.74% | 17.16% | 8.60% | 8.04% | 29.01% | 0.48% |

| Compostela Valley | 6.28% | 18.44% | 17.30% | 49.53% | 0.00% | 8.22% | 0.22% |

Of the three provinces in the region, Davao del Sur has the most number of LBP branches (8) and ATMs (34), while the rest of the provinces have an average of one LBP branch and seven ATMs. This is not surprising since the capital city of Region XI is situated in Davao del Sur. Accordingly, financial entities are plentiful and it is thus to be expected that the LBP would be the dominant payment conduit (as evident in its percentage of transaction cost of about 36.71% (775,243 beneficiaries)).

In most municipalities in all four provinces, payouts for the first two years were conducted by LBP through offsite and over-the-counter payments due to remoteness of these municipalities from the LBP branch. It may be less costly for the program since the LBP charged the lowest transaction fees. However, there is a trade-off in the schedule of payments, which were only conducted during weekends and holidays. Accordingly, less costly delivery of payments does not match with timely manner of deliveries of cash transfers. With the remotest municipalities in each of the provinces requiring 3 to 5 hours travel by public transport, the LBP as a payment conduit is no longer a practical conduit, even if it charges the cheapest transaction rate per beneficiary. Consequently, in all three provinces, except Davao del Sur, rural banks served the greatest number of beneficiaries in the different municipalities. Rural banks are not available in most municipalities of Davao de Sur. Thus beneficiaries were assigned to PhilPost, making it the next conduit to LBP to have served the most beneficiaries. For the other three provinces, rural banks are strategically located in each province making it a feasible choice of payment conduit not only for the program itself, but also for beneficiaries as well.

Globe Telecom is the most flexible payment conduit to deliver cash assistance in a timely manner since its service network reaches the farthest municipalities in the region. However, it is also the most expensive payment conduit. It charges higher transaction fees but offers a reliable and efficient service. With the extensive pressure on 4Ps to show that it is efficient and cost effective, DSWD ensures that it holds multiple competitive bids to minimize transaction fees charged by PSPs.

Under the competitive procurement process for choosing payment conduits, MLhuillier replaced Globe Telecom as payment provider in areas previously served by the latter because it charged a lower transaction fee; much lower than rural banks and PhilPost. Furthermore, there is one PhilPost office for every municipality in all four provinces, but there is an average of 14 MLhuillier agents in each three provinces (Davao del Sur, Davao del Norte and Davao Oriental), but not one in Compostela Valley province. The majority of the municipalities of Compostela Valley province are closely situated near Davao del Norte.

It follows that—other than assigning beneficiaries to rural banks for practical reasons of cost and time required to deliver cash assistance—PhilPost and MLhuillier, which charged similar fees to rural banks, were also engaged by 4Ps since LBP had ceased to conduct OTC in 2012. This was developed after the request of LBP for exemption from certain regulatory requirements in rendering payout service to the 4Ps beneficiaries was granted by Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (Central Bank of the Philippines). This also explains why other conduits served beneficiaries in all capital cities and municipalities of each province even with the presence of LBP.

It is evident from Table 5 that competition for 4Ps contracts to deliver cash transfers is effective. Even with the flexibility of Globe Telecom’s service, because other PSPs can provide the same service at a lower cost, contracts were awarded to the lowest bidding PSPs.

5.3. Indicators of Outcome and Cost Efficiency

A synoptic account of the average number of beneficiaries served on a per set, per province, per municipality and on a per payment scheme (from 2008–2013) was undertaken in order to compare the performance outcome of the different PSPs engaged by 4Ps. Assessing the performance of the various payment schemes in terms of the average number of beneficiaries served during the research period demonstrated that—while the LBP served as the sole payment conduit for the first two years—the average number of beneficiaries served showed that rural banks posted the highest outcomes in serving the most number of beneficiaries in the most number of municipalities in Region 11. Of the 49 municipalities in the region, 22 municipalities were served by the rural banks (Davao Oriental (8); Davao del Norte (4); Davao del Sur (4); and Compostela Valley (6)), and most of these municipalities are located far away from the capital city of each province. The LBP ranked next in terms of the number of beneficiaries served, with a total of 16 municipalities covered, and these were mostly the capital city or municipality of each province and municipalities located near the capital center. The Globe G-cash and the PhilPost as payment conduits showed highest outcomes in the remotest areas of all four provinces. In terms of cost efficiency, it is expected that the LBP as a payment conduit is the most cost-efficient PSP since it charged the lowest transaction fee as compared with the other conduits. Even if LBP ranked second in terms of the average number of beneficiaries served during the period under review, it nonetheless had the lowest total transaction costs. MLhuillier ranked second in terms of cost efficiency since it charged lower transaction fees as compared to rural/coop banks and PhilPost. However, its service is only prevalent in Davao del Sur and Davao del Norte. Of the three PSPs which charged the same transaction fee, rural banks are the most cost-efficient, with the greatest number of beneficiaries served. The PhilPost ranked next to rural banks in terms of cost efficiency, except in Davao del Sur where it ranked next to LBP. While the Globe G-cash may be the least cost-effective payment scheme, it nevertheless delivered payment to beneficiaries in the farthest and most remote areas in the region.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we have assessed the different payment schemes engaged by the 4Ps in delivering the cash benefits to the recipients in terms of their advantages and disadvantages, the cost and time required to deliver the cash assistance, competition for 4Ps contracts, 4Ps outcomes, and cost efficiency. Four main findings emerge from this empirical analysis.

In the first place, the choice of payment conduits comes with trade-offs between different features of the payment system. If program managers consider reducing costs to recipients, then they should choose a payment scheme that can deliver cash directly to beneficiaries. However, this is costly and poses security and corruption risks. Payment schemes including offsite over-the-counter payments by the LBP, rural banks, PhilPost, cooperative association, Globe G-cash and MLhuillier have speed, simplicity and flexibility advantages, but at the expense of predictability and security. Conversely, if the program managers seek to reduce program cost and security and corruption risks, then they should employ payment schemes using bank accounts, like cash-cards issued by LBP. This is not only advantageous to the program and the payment service provider in terms of cost reduction, ease of tracking payments, reconciliation and workload of agency staff, but it is also beneficial for recipients in terms of flexibility and convenience since they can choose when to withdraw cash and avoid long queues. However, the disadvantage of this payment system is that recipients may be unfamiliar with financial institutions and often experience anxiety in dealing with them (see Appendix A and Appendix B). Thus, in the case of 4Ps, some observers have noted that it is not recipients who actually access the payments through the ATM but rather the bank security guards, relatives, financial agents where the cash-cards are pawned, or moneylenders owed money by recipients. This often comes with a fee that reduces the benefits received by the beneficiaries.

Second, it is advantageous for 4Ps to consider a payment approach that uses mainstream payment instruments, such as the LBP, rural banks and PhilPost. In this study, these payment schemes are dominant in most municipalities and hence there is no need to deploy a special payment infrastructure. Instead established infrastructure can be used. This is especially true of PhilPost agencies. The option to engage these payment schemes is less costly, compared to limited purpose instruments provided by mobile phone companies. Costs borne by mobile companies are passed on to the program. For example, Globe G-cash charges a service fee 68 percent higher than LBP.

Third, as we have seen, competition for 4Ps contracts by payment service providers has helped improve payment service quality and reduce costs. The LBP’s Procurement Management Committee conducts 4Ps bidding processes twice a year for competing PSPs. Payment conduits that are the lowest bidders and can provide timely and efficient delivery of payments are chosen. Thus, MLhuillier replaced Globe G-cash for these reasons.

Fourth, the program’s outcomes and cost efficiency of 4Ps in terms of the number of beneficiaries served is greatly influenced by the commitment of the PSP to deliver the cash benefits to the recipients in a timely manner. The presence of rural banks in Davao region are limited to only four branches, unlike PhilPost and MLhuillier, and yet it has served the greatest number of beneficiaries. Zimmerman et al. [20] found that while different PSPs may have different reasons for involvement in 4Ps, corporate social responsibility (CSR) was a common motivation. The LBP charged the lowest service fee since its core motivations are CSR and responding to a policy mandate and not to earn direct financial benefits from the program. Following personal communication from an LBP official, Landbank has carefully calculated the operating/administrative costs in the conduct of the cash transfer payment and the Php24.00 transaction fee is enough to cover all these costs. Another plausible reason for charging the lowest fee is the fact that DSWD is not only a partner agency but also a valued bank’s client. According to Zimmerman et al. [20], other payment conduits, such as PhilPost, MLhuillier, Globe G-cash and the rural banks, had varying reasons for involvement with the program. For instance, PhilPost joined 4Ps to improve its viability in the wake of a rapidly declining postal business. Similarly, MLhuillier competed for 4Ps payments for both strategic and financial reasons. Globe was motivated to join 4Ps as an opportunity to test and subsequently prove that its platform could be successful for government payment purposes. Rural banks chose to work with 4Ps primarily for the fees it earns and for potential new customers. All these conduits experienced the challenges of security in delivering payments, which also influenced their operational and cost efficiencies. Despite these difficulties, they continue involvement with the program on the basis of CSR.

The present practice of 4Ps of pursuing systems of mixed payments that can be adapted to the conditions and circumstances of the geographical areas where the payments are made is laudable. This addresses major challenges with the program in making precise payments on time. No single PSP seems to be optimal in all respects. It should be stressed that the choice of PSP rests not only on cost effectiveness, but also reliability and auditability. As Langhan et al. [16] have observed, cash transfer programs everywhere are critically dependent on the development and deployment of a reliable, auditable and cost effective disbursements and payment system.

Finally, our findings spawn suggestions for future research. These stem in part from the limitations of our study due to the unavailability of data. For instance, the use of more disaggregated data will provide a more comprehensive assessment of the efficacy of different payment schemes. Similarly, analogous research on other regions in the Philippines will shed light on whether the findings in our paper are unique to the provinces of Davao region or whether the findings apply more generally to provinces to other regions as well. Nevertheless, our paper has highlighted the importance of considering the needs of the intended beneficiaries in the design of payment options. In particular, policy design should take into account the transaction costs, security and risks, speed and timeliness, acceptability, resilience and flexibility of varying payment options.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the assistance extended by the staff of the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD), Region XI, Davao City, Philippines for our data collection. We would also like to thank three anonymous referees for insightful comments on an early draft of the paper.

Author Contributions

The lead author, Catubig did the majority of the tasks, including data collection, analysis and conceptualization and writing of the document. The co-authors, Villano provided inputs in the conceptualization of the paper, analysis and comments in the discussion of results; Dollery provided inputs in conclusions and editorial aspects.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A: Key Criteria for Assessing Cash Delivery Options—Viewpoint of Conduits

| Criteria | LBP (Over the Counter) | LBP (Cash Card) | PhilPost (Over the Counter) | Rural Banks (Over the Counter) | MLhuillier (OTC/Cash in Envelope) | Globe G-Cash (Cash in Envelope) | Cooperative (Cash in Envelope) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Program Objective | Distribute the correct amount of benefits to the right people at the right time at a minimum cost | Yes, low cost | Yes, low Cost | Yes, medium cost | Yes, medium cost | Yes, medium cost | Yes, high cost | Yes, medium cost |

| Delivery Options and Existing Infrastructure | Six delivery options in the area and good mobile phone coverage | Infra- Limited | Infra-Limited to city centers | Infra-Present in all municipalities | Infra- None | Infra- Limited | Infra- High coverage | Infra- None |

| Costs | Operating cost | High cost | Low cost | High cost | High cost | High cost | High cost | High cost |

| Security/Control/ Risks | Monitoring/Auditing | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | High risk | High risk | High risk | High risk |

| Corruptions/ Lawless elements/Loss | High risk | Low risk | High risk | High risk | High risk | High risk | High risk | |

| Human Resources | Number of Staff Required | More | Less | More | More | More | More | More |

| Speed | Time for delivery | Longer time | Longer time | Shorter time | Shorter time | Shorter time | Shorter time | Shorter time |

| Resilience | Possible Disruption | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Scale | Target Population | Assigned municipality | City centers and nearby areas | Each Municipality | Assigned municipality | Assigned municipality | Assigned municipality | Assigned municipality |

| Frequency of Payment | Bimonthly | Bimonthly | Bimonthly | Bimonthly | Bimonthly | Bimonthly | Bimonthly | |

| Flexibility | Timing | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Source: Authors’ own assessment.

Appendix B: Key Criteria for Assessing Cash Delivery Options: Viewpoint of Beneficiaries/Recipients

| Criteria | LBP (Over the Counter) | LBP (Cash Card) | PhilPost (Over the Counter) | Rural Banks (Over the counter) | Mlhuillier (OTC/Cash in Envelope) | Globe G-Cash (Cash in Envelope) | Cooperative (Cash in Envelope) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost | Opportunity costs | |||||||

| (Long queues) | High | Low | High | High | High | High | High | |

| Transportation cost | Low | High | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | |

| Security Risk | Lawless Elements | High | Low | High | High | High | High | High |

| Speed/Timeliness | In Terms of Accessibility | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Flexibility | Collecting the benefits | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Acceptability | Familiarity of Process | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| and types of payment | ||||||||

| schemes | ||||||||

Source: Authors’ own assessment.

Appendix C: Average Beneficiaries and Cities/Municipalities Served Per Payment Scheme

| Set | No. of Cities/Municipalities/Per Set | LBP (OTC) | LBP (CC) | Globe G-cash | Rural Bank | PhilPost | Mlhuillier | Coop |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Set 1 | 3 | 4949 (3) | 6441 (3) | 3603 (2) | 4818 (3) | 75 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Set 2 | 8 | 18,200 (8) | 29,036 (8) | 21,204 (6) | 10,657 (4) | 16,363 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Set 3 | 14 | 5944 (14) | 7019 (12) | 1680 (4) | 1857 (8) | 409 (3) | 2 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Set 4 | 21 | 22,479 (12) | 27,566 (8) | 13,698 (11) | 21,439 (19) | 2816 (7) | 315 (6) | 2223 (1) |

| Set 5 | 36 | 13,946 (14) | 19,530 (16) | 0 (0) | 20,826 (26) | 9822 (17) | 6872 (15) | 228 (2) |

| Set 6 | 44 | 0 (0) | 3133 (16) | 0 (0) | 4219 (25) | 13,006 (24) | 3777 (16) | 1006 (1) |

Notes: Source: Authors’ own summary; Average was taken using those who availed the services of the payment conduits. Figures in parentheses denote the number of cities/municipalities, which adopted the indicated payment scheme. Each city/municipality can adopt more than one payment conduits at a time.

References

- DFID. Social Transfers and Chronic Poverty: Emerging Evidence and the Challenge Ahead; Deparment for International Development: London and Glasgow, UK, 2005.

- Barrientos, A.; DeJong, J. Reducing Child Poverty with Cash Transfers: A sure Thing? Pol. Rev. 2006, 24, 537–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrington, J.; Slater, R. Introduction: Cash Transfers: Panacea for Poverty Reduction or Money Down the Drain? Dev. Pol. Rev. 2006, 24, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barca, V.; Hurrell, A.; MacAuslan, I.; Visram, A.; Willis, J. Paying Attention to Detail: How to Transfer Cash in Cash Transfers. Ent. Dev. Microfinance 2013, 24, 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, J.; Bohling, K. Striving for E-Payments at Scale. The Evolution of the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program in the Philippines; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- DFID. Scoping Report on the Payment of Social Transfers through the Financial System; Bankable Frontier Associates: Boston, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, L.; Olfindo, R. Overview of the Philippines’ Conditional Cash Transfer Program: The Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (Pantawid Pamilya); World Bank: Manila, the Philippines, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bangsal, N.; Asuncion, R. Accountability Mechanisms in the Implementation of Condtional Cash Transfer Program (CCTs): Policy Brief; Congressional Policy, Budget and Research Department (CPBRD): Quezon City, Philippines, 2011.

- Harvey, P.; Haver, K.; Hoffman, J.; Murphy, B. Delivering Money: Cash Transfer Mechanisms in Emergencies; The Cash Learning Partnership (CaLP): London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Devereux, S.; Vincent, K. Using Technology to Deliver Social Protection: Exploring Opportunities and Risks. Dev. Pract. 2010, 20, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, S.; Hove, F. Cheaper, Faster, Better? A Case Study of New Technologies in Cash Transfers from the Democratic Republic of Congo; Mercy Corps and Oxford Policy Management: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Grosh, M.; del Ninno, C.; Tesline, E.; Ouerghi, A. From Protection to Promotion: The Design and Implementation of Effective Safety Nets; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Beswick, C. Distributing Cash Through Bank Accounts: Save the Children's Drought Response in Swaziland; FinMarkTrust: Marshalltown, South Africa, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Forcier, N. Report on Cash Transfer Modalities for South Sudan. Available online: http://www.forcierconsulting.com/../uploads/2013/05/2012_Forcier-FAO-RSS-Report-on-Cash-Transfer (accessed on 8 February 2015).

- Nigenda, G.; Gonzalez-Robledo, J. Lessons Offered by Latin American Cash Transfer Programmes Mexico’s Oportunidades and Nicaraguas’ SPN: Implications for African countries; DFID Health Systems Response Centre: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Langhan, S.; Kilfoil, C.; Agar, J.; Murphy, B. Identification of Appropriate Alternative Delivery Mechanisms for the Cash Transfer in the Context of the Pilot Social Cash Transfer Scheme in Mchinji District, Malawi; UNICEF and Government of Malawi: Lilongwe, Malawi, 2010.

- O’ Brien, C. A Guide to Calculating the Cost of Delivering Cash Transfers in Humanitarian Emergencies with Reference to Case Studies in Kenya and Somalia; Oxford Policy Management: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo, P.; Ponce Jarrín, J. Efficient Delivery of Cash Transfers to the Poor: Improving the Design of a Conditional Cash Transfer Program in Ecuador; Institute for International Economic Policy, 2007. Available online: https://www.gwu.edu/~iiep/assets/docs/papers/Carrillo_IIEPWP8.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2015).

- Bold, C.; Porteous, D.; Rotman, S. Social Cash Transfers and Financial Inclusion: Evidence from Four Countries; The Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP): Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, J.; Bohling, K.; Parker, S. Electronic G2P Payments: Evidence from Four Lower-Income Countries; The Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP): Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, C.; Hove, F.; Smith, G. Factors Affecting the Cost-Efficiency of Electronic Transfers in Humanitarian Programmes; Oxford Policy Management: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Oberländer, L.; Brossman, M. Electronic Delivery Methods of Social Cash Transfers. [Discussion Papers on Social Protection]. Available online: https://www.giz.de/expertise/downloads/giz2014-en-electronic-delivery-methods-of-social-cash-transfers.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2015).

- Chandy, L.; Kharas, H. The Innovation of Revolution and Its Implications for Development; Brookings Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Aker, J.; Boumnijel, R.; McClelland, A.; Tierney, N. Zap it to Me: The Short-Term Impacts of a Mobile Cash Transfer Program; Center for Global Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- CGAP. Striving for E-Payments at Scale: The Evolution of the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program in the Philippines; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gusto, A.; Roque, E. Delivering Cash Grants to Indigenous Peoples Through Cash Cards Over-the-Counter Modalities: The Case of 4Ps Conditional Cash Transfer Program in Palawan, Philippines; Institute for Money Technology and Financial Inclusion (IMTFI): Irvine, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).