Abstract

There is limited theoretical understanding and empirical evidence for how international new ventures legitimate. Drawing from legitimation theory, this study fills in this gap by exploring how international new ventures legitimate and strive for survival in the face of critical events during the process of their emergence. It is a longitudinal, multiple-case study research that employs critical incident technique for data collection, analysis, and interpretation. Following theory driven sampling, five international new ventures were selected that were operating in the software sector in the UK, and had internationalized and struggled for survival during the dotcom era. Grounded in data, this study corroborates a number of legitimation strategies yielded by prior research and refutes others. It further contributes to our understanding of international new venture legitimation by suggesting new types of legitimation strategies: technology, operating, and anchoring. Studying international new ventures through theoretical lenses of legitimation is a promising area of research that would contribute to the advancement of international entrepreneurship theory.

1. Introduction

We view international new ventures (INVs) as ventures that have no prior corporate history in the industry and no prior presence in international markets [1]. During the process of their emergence, INVs usually experience three types of liabilities—newness, smallness, and foreignness—that either individually, or in combination, can increase the risk of INVs’ potential failure [2]. Such ventures overcome these kinds of liabilities when they become legitimate [3,4,5,6,7].

Legitimacy is approached as “a generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, beliefs, and definitions” ([8], p. 574). Undertaking activities to generate legitimacy both enhances new venture survival and facilitates the transition to other forms of organizing activities [9]. The acquisition of legitimacy or the failure to legitimate has a differentiated effect on INVs that is expressed as legitimacy threshold “… below which the new venture struggles for existence and probably will perish and above which the new venture can achieve further gains in legitimacy and resources” ([6], p. 427).

A number of reviews have been recently conducted that provide an excellent account of the status of the emerging field of international entrepreneurship [10,11,12,13,14]. The findings from these reviews highlight, inter alia, the importance of overcoming liabilities of newness, smallness, and foreignness for INVs, and point to the scarcity of extant research on INV legitimation. With this paper we fill in this gap by furthering our understanding of INV legitimation by exploring in depth how INVs acquire legitimacy and strive for survival in the face of critical events during the process of their emergence. In this quest, we draw from legitimation theory.

Driven by the nature of the research question, as well as by the urge to advance our theoretical understanding of INV legitimation, we adopt a longitudinal multiple-case study methodology [15]. To capture the above-mentioned differentiated effects, we employ the critical incident technique to collect, analyze, and interpret the data [16,17,18]. We define an event as critical when it deviates significantly, either positively or negatively, from what is normal or expected [19].

Grounded in data, we corroborate a number of legitimation strategies yielded by prior research and refute others. At the same time, we further contribute to our understanding of INV legitimation by suggesting new types of legitimation strategies, mainly technology, operating, and anchoring. Additionally, we develop a set of tools and techniques to research critical incidents in INVs.

We continue the paper by positioning INVs within legitimation theory. We then present the methodology and methods employed to address the research question. Findings are presented and discussed next. We conclude the paper by proposing an agenda for future research to advance international entrepreneurship literature in the area of INV legitimation.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Positioning and Contextualizing the Research

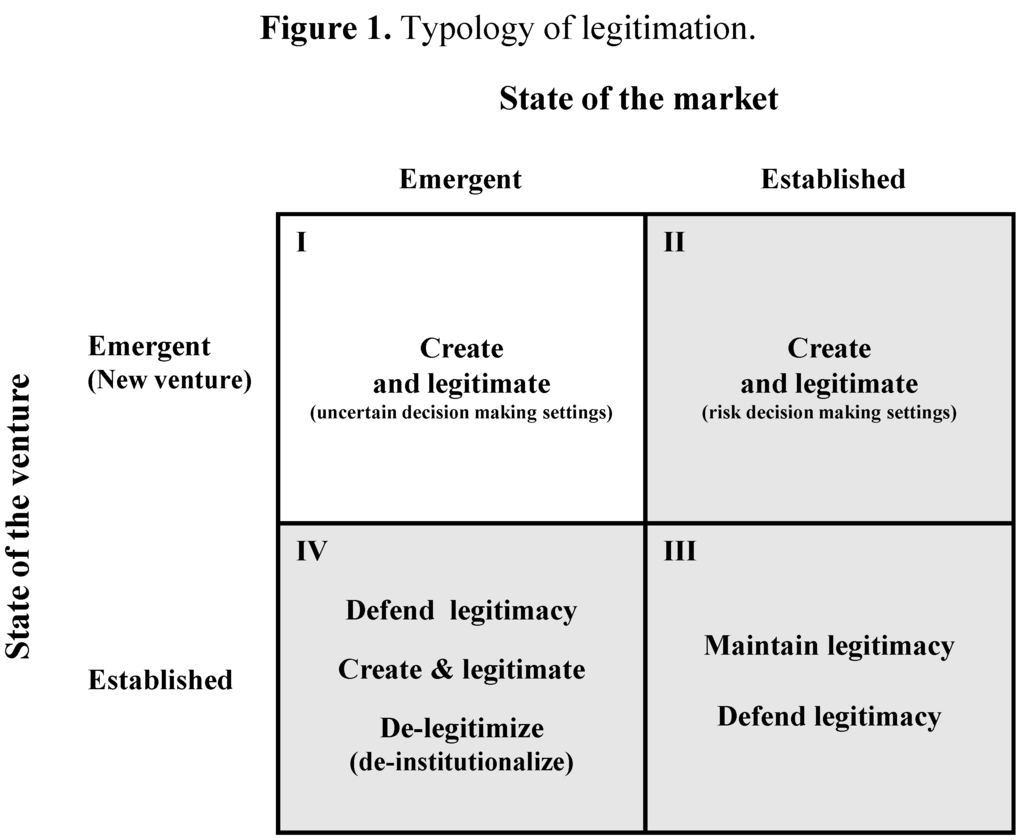

We draw from legitimation theory in order to position INV legitimation research. We put forward a typology of legitimation (Figure 1) by cross-tabulating two research streams that emerge from legitimation literature. The typology of legitimation is built following the method of constructing typologies by reduction [20]. According to Glaser [20], all typologies are based on differentiating criteria, e.g., being internal or external to a concept, or being delineated by its dimensions or degrees. Constructing a typology by reduction is achieved by cross-tabulating the internal or external distinction of a concept. For example, one dimension might represent the life continuum of a firm: young vs. old; start-up vs. established; success vs. failure; or still in business vs. out of business. The other dimension might be related to a unit of analysis and represent its continuum by using appropriate coding families [20] or logical simplification [21], e.g., total vs. partial; dependent vs. independent; or uncertainty vs. risk. One research stream deals with the state of the venture—emergent vs. established, hence, the creation and legitimation of new ventures, and the maintenance of legitimacy in already established ventures [22]. Another research stream looks at the state of the industry the venture operates in—emergent vs. established, hence, legitimation of ventures in emergent and established industries [4].

Figure 1.

Typology of legitimation.

The research on INV legitimation is positioned within quadrants I and II (Figure 1). Researchers doing research in quadrant I and II may delve into how these ventures (be these independent start-ups or intrapreneurship ventures) create and legitimate themselves in an attempt to reach the legitimacy threshold. The research in quadrant I is characterized by uncertain decision-making settings, whereas the research in quadrant II—by risk decision-making settings. The difference between the two is that in the former, the possible outcomes of decisions to pursue an opportunity, and the probability of those outcomes, are unknown [23]. An example of such uncertain decision-making settings is the dotcom era, during which decisions were made under conditions of technology and market uncertainty as well as goal ambiguity [24,25,26,27].

Researchers conducting research in quadrant III are concerned with how established ventures maintain their legitimacy or the status quo [22], or defend their legitimacy [28]. For example, well-established ventures may build legitimacy-based barriers to entry into their domain by changing the relative importance of legitimacy dimensions, raising the legitimacy threshold, and altering the perceptions of competitors’ performance. In quadrant IV, researchers might inquire into how established ventures defend their legitimacy when the market they operate in is in a state of emergence, for example, when it is disrupted by the introduction of radical innovation or new organizational forms, or a new social order. In the face of such threats, such ventures have the options of trying to defend their status quo [28] or to de-legitimize [29] their existing practices to conform to new realities. Researchers here may also study how established ventures create and legitimate their products or services in international emerging markets, or even how new industries or sectors of an economy are created.

The focus of the present study is on how INVs create and legitimate themselves in markets that are also in the process of emergence; hence, this study is positioned within quadrant I of Figure 1. A representative example of such uncertain decision-making settings is the dotcom period [27] that provides the context for the present study.

During the dotcom boom, the future prospects, sometimes even exaggerated [25], of a technology, an innovation, a market, or a product gave birth to several myths regarding the new economy, including the business cycle is dead or business decisions could ignore old rules about the marketplace [30,31]. Many believed that the Internet would have major impact on global business by 2001 [32]. Visionary predictions of the e-business, like brands will die, prices will fall, and middlemen will die were driving the valuation of virtual firms to the level of an Internet Bubble [24] that burst in 2000.

In such environments as dotcom, entrepreneurs and their stakeholders have difficulties in understanding the nature of INVs, in making realistic predictions about the growth potential of the markets, and in learning and adjusting their behaviors as industries emerge. Moreover, entrepreneurs’ concerns are not only about legitimizing their international ventures, but also about contributing to the creation and the establishment of new technical norms and new cognitive patterns of behavior [33].

2.2. International New Venture Legitimation

The extant research on INV legitimation is in its embryonic stage. Recent attempts to explore this intersection highlighted a number of challenges that await entrepreneurs in the process of INV legitimation [7,33,34,35]. How legitimacy and identity are constructed over time, and whether the legitimacy threshold is ever reached are considered major challenges in INVs research [7]. During their lifetime, INVs go through various types of behavior, and recurrent activities and patterns of interaction, in order to legitimize, as well as undergo a changing context within which the venture struggles to reach the legitimacy threshold. For example, INVs’ members may use their position in the venture to promote their preferred agendas, thereby exposing them to both opportunities and risks [7]. On one hand, the diversity of different behaviors may lead to consent over the identity of the venture and an alignment of internal and external legitimacy; on the other hand, it may lead to contested identities and a misalignment of the legitimation process. Drori et al. ([7], p. 734) conclude that internal legitimacy is critical to construct a sufficiently robust nascent organizational culture and to enhance creative activity, while external legitimacy is necessary for the acquisition of resources and the attraction of customers and clients.

INVs seek to mitigate liabilities of newness, smallness and foreignness by partnering or affiliating with highly regarded organizations [34,35]. Such partnerships or alliances allow INVs to enter international markets, enhance their market position and authority, acquire resources and skills, as well as mitigate the risks associated with rapid internationalization—eventually leading to INV legitimation and legitimation threshold. However, such partnerships are not always successfully implemented, as Groen et al. [34] found, due to tensions within the entrepreneurial team, disappointments and inefficiencies in running the venture, loss of application opportunities due to the alliance breakdown, delay in bringing the technology to the market due to insufficient funding, or lack of support from the network. By forming such partnerships or alliances, INVs may find themselves in captivity as a captive industry supplier, captive dyadic partner, or captive market leader [35]—a state that may decrease the likelihood INV survivability. According to Turcan [35], the dynamics in the relationship between the captive INV and its reputable partner may also change when INV potential is realized, i.e., legitimacy threshold is reached: INV may exit the partnership and continue on its own, including through an IPO; it can be internalized by its partner, or acquired by another organization.

Recently, Turcan and Fraser [33] explored the process of emergence of an INV from an emerging economy and the effect such venture has on the process of industry creation in that economy. Turcan and Fraser [33] found that in order for an INV to achieve legitimacy in an emerging industry located in an emerging economy, and successfully internationalize, it shall design a robust business model targeting both internal and external stakeholders, engage in persuasive argumentation invoking familiar cues and scripts, engage in political negotiations promoting and defending incentive and operating mechanisms, and overcome the country-of-origin effect by legitimating their technology. In the context of new industry emergence, such INV legitimation efforts are also directed towards changing and creating new structural meanings that helped the new, emerging industry reach what Turcan and Fraser [33] call industry legitimation threshold.

2.3. New Venture Legitimation

Given that the extant knowledge regarding the legitimation process in INVs is relatively scant, we turn to the literature on new venture legitimation in an attempt to identify concepts and theoretical perspectives that might be applicable to INV legitimation (within quadrants I and II, Figure 1); for a comprehensive review of legitimation strategies literature, please refer to Turcan et al. [36].

The process of new venture emergence can be understood and predicted by viewing it as a quest for legitimacy [37] during which a new venture seeks different strategies to establish or build legitimacy [4]. Zott and Huy [38] suggest grouping legitimation strategies of new ventures into four symbolic legitimation strategies: credibility, defined as personal capability and personal commitment to the venture; professional organizing, defined as professional structures and processes; organizational achievement, defined as partially-working products and technologies, venture age, and number of employees; and quality of stakeholder relationships, defined as prestigious stakeholders, and personal attention.

Hargadon and Douglas [39] introduce the notion of robust design and argue that robust design mediates between legitimized design and technical innovation, reduces the uncertainty linked to the new activity, and ensures that the main stakeholders would consider the new activity legitimate. According to Hargadon and Douglas [39], the major challenge for the entrepreneurs lies in finding familiar cues that locate and describe new ideas without binding the new venture’s stakeholders too closely to the old ways of doing things. That is, as new technologies emerge, entrepreneurs and innovators must find the balance between novelty and familiarity, between impact and acceptance. An interesting finding emerged in the research by Wilson and Stokes [40] who found that the most appropriate legitimation strategy available to new ventures is the manipulation strategy.

The extant research on legitimation points to external and internal legitimacy, and suggests the positive effect of external and internal legitimacy on new ventures’ growth and survival [9,41,42,43]. It also points to the fact that external and internal legitimacy are interdependent, rather than independent [41]. New ventures can acquire external legitimacy by associating or partnering with successful and established external entities. Extant research suggests that new ventures that acquire legitimacy externally by forming alliances with established firms gain more from their new products than new ventures that did not form such alliances [42].

Internal legitimacy can be acquired by new ventures through four types of actions: market, scientific, locational, and historical [42]. It has to be noted that, in their paper, Rao et al. [42] apply the concept of ‘new venture’ to ‘new product introduction’, that is, the emergence of a new venture in an established market (quadrant II, Figure 1); in spite of this, for the purpose of this paper, their model of legitimation strategies is an informative one. Through market legitimacy, new ventures are trying to convey to their stakeholders that they have the market-based capabilities to operate effectively in their market. This could be achieved, for example, by appointing a non-executive director with prior experience in this or similar industries. Scientific legitimacy is about signaling to the stakeholders that the new venture has the technology-based capabilities needed to operate in the industry. Here, recruiting eminent scientists could be one of the options. Locational legitimacy conveys to the stakeholders that the new venture is capable of deriving a differential advantage from its geographical location. Finally, through historical legitimacy, new ventures are trying to communicate the prospects of future performance on the basis of their past performance to their stakeholders. As per our definition of INVs provided above, this type of legitimacy has limited applicability to INVs as these ventures have no prior (corporate) history.

In their efforts to gain legitimacy, new ventures’ ideas change under various external pressures, such as customers, competitors, investors, suppliers, and incubators [42]. Davidsson et al. [44] found that that the amount of change and the external pressure to change is greater after the start-up phase than in the pre-start-up, formative stage. These authors further suggest that more changes of the venture idea are also to be expected in situations when these new ventures depend on external finance, rely on a dominant player, and are located in incubators.

Such legitimation activities become critical, since, in their pursuit for legitimacy, entrepreneurs face conflicting expectations about fitting in with the established rules on one hand, and the need to stand out as a rule breaker in order to differentiate themselves on the other [45]. However, there is a lack of empirical research regarding the examination of the process taking place in INVs in terms of the rapid and short life span, as well as how the initial conditions of their founding generate external and internal legitimacy [7]. This paper aims to address this gap by exploring how INVs acquire legitimacy during the process of their emergence.

3. Research Methodology

Given the limited theory and evidence for how INVs legitimate, we adopted a longitudinal multiple-case study methodology for the purpose of theory building [15]. We explore how INVs acquire legitimacy and strive for survival in the face of critical events during the process of their emergence. Following a theory driven sampling (quadrant I, Figure 1), we purposefully selected five INVs for the study. Table 1 provides a brief summary of the cases; for confidentiality reasons, interviewees’ and companies’ names are disguised throughout the paper.

Further sampling criteria were developed in order to select case companies as well as the empirical setting of the study. First, quadrant I in Figure 1 informed us of the need to look for INVs that were emerging in a new, emerging industry. Second, we used the internationalization gap to define an international new venture. The internationalization gap is the time that elapses from the emergence of a new venture until the moment of its internationalization; e.g., an internationalization gap of zero would denote instant internationalization. Third, since three out of five case companies have ceased trading, it became imperative to control for attribution errors, which are defined as a pattern whereby people tend to take credit for positive outcomes and attribute negative outcomes to external factors [46]. Indeed, one of the challenges when researching critical events, especially those that deviate negatively from what is normal or expected, is to control for such attribution errors.

In the present study, we controlled for attribution errors by confining the study to a homogeneous empirical context. By doing so, it allowed us to control for the effect of the external environment on selected cases, such as legislation, market size, market structure across industries and countries, and the effect of time. In the present study, the sampled INVs were operating in the software sector in the UK, and had internationalized and struggled for survival during the dotcom era between 1999 and 2003, inclusive. The potential effect of resource bias was also controlled for by defining a small venture as a venture having less than 100 employees [47]. To further minimize the potential effect of attribution errors, data collected from entrepreneurs were corroborated by data collected from their stakeholders and secondary sources; data collection and triangulation are summarized in Table 2.

Data Collection and Analysis

Data were collected from entrepreneurs/owners, and corroborated by data collected from their stakeholders, such as investors, strategic advisors, liquidators, policy makers, and business journalists, in four phases from 2000 through 2005. On average, an interview lasted approximately sixty minutes. All interviews were recorded with the interviewee’s permission, and transcribed verbatim immediately afterward. The interviews were semi-structured in the form of guided conversations; to ensure some comparativeness between the responses, and allow sufficient control over the interview in order to ensure that the research objectives were met, an interview guide was designed. Twenty-four semi-structured, in-depth interviews were conducted yielding approximately 150 pages of interview data.

Databases were created for each case with the aim of organizing and documenting the data collected, including primary and secondary data, thus enhancing the reliability of the research. The use of secondary data was primarily seen as a means to thoroughly prepare for the fieldwork, especially when studying critical events. Such an opportunity to get access to an entrepreneur with such (perceived as negative) experience was seen as potentially unique; therefore, it was deemed that as much as possible should be learned about the entrepreneur and the company before the interview. Secondary data were also used to detect potential cases on the bases of sampling selection criteria, to identify potential stakeholders who could corroborate the consistency of the information reported by interviewees, and to compare and cross-check written and published evidence with what interview respondents had reported.

Table 1.

Summary of case companies.

| Case Company | Business Description | Founded (Year) | Mode of Founding | Emergence of New Business Idea | Gone International | Growth Path | Number of Employees (at its Peak) | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finance-Software | B2B platforms for financial service industry | 1996 | Management buy-out | 1998 | 1998 | Organic growth | 60 | Product at least 12 months to soon to the market Ceased trading in 2004 |

| Project-Software | Tools to estimate project costs | 1992 | Start-up | 1995 | 1997 | VC backed | 12 | Liquidated in 2001; bought IP from liquidator Resurrected as Phoenix in 2001 |

| Tool-Software | Tools to estimate and test smart cards | 1985 | Start-up | 1993 | 1995 | Organic growth | 130 | Smart-card technology adopted globally in 1995 Moved to profitability in 1995 |

| Mobile-Software | Platform to integrate mobile workforce data to HQ | 2000 | Start-up | 2000 | 2000 | VC backed | 105 | Were behind revenues and platform development in 2001 Ceased trading in 2002 |

| Data-Software | Data warehouse to convert data into information | 1998 | Spin-out | 1998 | 1999 | VC backed | 40 | The strategic partner announced similar market development plans in 2000 Ceased trading in 2001 |

Table 2.

Data collection and triangulation.

| Phase 1 1 2000 | Phase 2 2001–2003 | Phase 3 2004 | Phase 4 2005 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

1 Interviewees are listed in the order they were interviewed; 2 The internationalization team at Scottish Trade International was assisting small and medium companies in their internationalization efforts; 3 The software team at Scottish Trade International focused on coordinating the internationalization efforts of Scottish software firms; 4 This business correspondent was working for the ‘Business a.m.’ newspaper and was responsible for tracking the evolution of nineteen ‘next generation’ entrepreneurs who were involved in various high-technology start-ups. The case companies were among those nineteen; 5 This liquidator was appointed as a receiver to Project-Software; 6 This venture capitalist invested in Project-Software and Data-Software and rejected funding to Tool-Software; 7 Scottish Enterprise is the Scotland’s economic, enterprise, innovation and investment agency; 8 This business strategy consultant consulted Tool-Software.

Data were collected and analyzed following the critical incident technique (CIT) that has its origins in the research undertaken by Flanagan [16]. CIT is defined as “... a qualitative interview procedure that facilitates the investigation of significant occurrences (events, incidents, processes, or issues) identified by respondents, the way they are managed, and the outcomes in terms of perceived effects” ([17], p. 56). CIT guidelines for in-depth interviewing were followed in all interviews [16,17]. The first step in the data analysis process, according to CIT, is to describe the incidents [16]. As maintained by Dubin [21], the very essence of description is to name the properties of things, and the more adequate the description, the greater the likelihood that the concepts derived from the description will be useful in subsequent theory building.

The exploration and description of each case were centered on critical events and had the inception of the company as a point of departure. The summaries of critical events for each case are presented in the Appendix. The process of coding was driven by the constructs derived from the literature, such as, market legitimacy and technology legitimacy, as well as by open, substantive coding. Quotes from interviews were used extensively to illustrate the events, incidents, processes and issues that had, to various degrees, had an impact on the process of legitimization. In parallel, theoretical memos were developed while transcribing and coding in NVivo.

The second step in the data analysis as per CIT is to choose a frame of reference so that it makes it easier and more accurate to classify and analyze the data. Initially, the locale of events [48] was identified, namely the entrepreneur, firm, home market, and international market levels. Then, four distinct time periods were identified that helped mapping the chronological flow of critical events, namely the emergence of new international business ideas, international expansion, a critical juncture, and beyond it.

The above frames were structured in NVivo around the event-listing matrix format that allowed a good look at what led to what, when, and why [48]. The content of the event-listing matrix emerged after the initial ‘free coding’ or open coding [20] for each case was completed, and each case was explored and described in detail. The third step in the data analysis is category formulation, which represents an induction of categories from the basic data in the form of incidents [16]. During this process, the analysis moved from open codes through to theoretical codes.

The last step in data analysis, according to CIT, is to determine the most appropriate level of specificity-generality to use in reporting the data. In this study, middle-range theorizing helped manage the complexity of data. According to Weick ([49], p. 521), middle-range theories are solutions to problems that contain a limited number of assumptions and considerable accuracy and detail in the problem specification. This approach led to the emergence of a framework of INV legitimation presented in Table 3. Grounded in data, six legitimation strategies emerged that INVs pursue in their quest for legitimacy (Table 3). Four of these, namely market, technology, locational, and operating legitimation strategies, relate to the process of acquiring internal legitimacy, whereas the remaining two, anchoring and alliance, relate to the process of gaining external legitimacy.

Table 3.

International new venture legitimation.

| Technology Legitimation Strategy | Market Legitimation Strategy | Operating Legitimation Strategy | Locational Legitimation Strategy | Alliance Legitimation Strategy | Anchoring Legitimation Strategy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aim | To validate the innovation/know-how | To better understand the target market | To have an optimal organizational gestalt | To overcome the disadvantage of foreignness | To mitigate the risk of newness and smallness | To intentionally misrepresent the facts |

| Target | Large enterprise players | Board of directors Potential customers | Potential investors (chiefly) | Potential customers Potential investors | Large enterprise players | Potential investors |

| Means | ‘Built-in’ capability Certification Recruiting key personnel | Non-executive directors Strategic advisors Large consulting firms VCs Referrals (weak ties) | Establish an office Hire employees Develop internal policy and operating procedures Develop incentive mechanisms Attract customers Generate first sale Get business education Procedural justice | Locate venture’s office abroad | International cooperative agreements Partnerships Joint-ventures | Asymmetry of information Hype business plans Accentuate positive and downplay negative Stretching the rules |

| (Perceived) benefits | Recognition Credibility Capability | Market-related capabilities | Efficient Professional | Local venture Potential for very high gains Possibility of early exit strategies Look big | Increased visibility, reputation, image, and prestige Likelihood to attract various types of investors Look big | Increased likelihood to attract venture funding |

| Challenges | To find early adopters willing to try new technology | Loss of control Goal misalignment | To set and commit to long-term outcome goals To develop performance benchmarks Risk of goal misalignment | Services do not travel, hence the need to develop a product-based business Internationalization dimension imposed by investors | Loss of control over own fate (as large enterprise players, alliance partners demand exclusive partnerships, hence captive partnership) | Ethical considerations Diminishing funding |

4. Findings

4.1. Technology Legitimation Strategy

During the process of opportunity emergence, entrepreneurs are primarily concerned with technology legitimacy, which pertains to how to validate an innovation that has been created to meet a need or solve a problem. This is in line with Johnson et al.’s [22] view of the legitimation process whereby the first stage in this process is concerned with the process of the emergence of an innovation. According to the data, technology legitimacy is, in a way, ‘built-in’ to the INV as owners/entrepreneurs have the technological, engineering, and scientific capability and credibility required to successfully research and develop the product. As entrepreneurs explained:

“… technical credibility really; we have one key developer; my co-owner and I are involved in the product architecture development.”—CEO of Project-Software.

“We span-out; prior to that we built advanced systems for a number of multinational companies, and in the meantime developed an IP. I left that company with a small team and IP and set up Data-Software. It was a service-based business. My ambition was to create a product-based business from that.”—CEO of Data-Software

Owners’/entrepreneurs’ capability and credibility are enhanced in situations where INVs emerge out of service-led businesses, thus bringing earlier success from a service-led business to the forefront of a newly emerging product-led or hybrid business model-based venture. In addition to the above, the data point to the recruitment of key personnel as another way of legitimizing new technology or innovation:

“When we adopted new technology, we did have to bluff quite a lot. We recruited people from banks and insurance companies; so, we gradually brought in the industry knowledge that we ourselves did not have. But when our potential customers decided to use this new technology, the fact that we did not come from financial service was less important to them; important to them was that we knew this technology.”—CEO of Finance-Software

“We did a project for a large computer and mobile manufacturer, and we were left with the software, and decided to do something with it, for example develop it as a tool. We created a tool, the next step then was to see where it can be used, and started hunting out key players.”—CEO of Tool-Software

The data further point to certification by large organizations as another activity aimed at validating the new technology. Through certification, INVs achieve two primary goals. One, they acquire recognition and credibility as being capable of successfully applying the new technology in the marketplace. And two, they gain hands-on experience in how to design, develop and implement the new technology, as was the case of Finance-Software:

“We became an authorized [technology] center, which was actually quite nice, as it started to make us look a lot bigger than we were. Because it was an early adopted technology, you could not be a smaller organization, because people would expect early adopters to be big organizations. Up until then we’d just been a group of R&D engineers which did not differentiate us; but as soon as we became an authorized [technology] center, we had the classic USP.”—Marketing Director of Finance-Software

As a result, a perception is constructed among INV’s outside stakeholders as being a large and important player in the newly created market, and at the same time it gives that INV a source for differentiation.

4.2. Market Legitimation Strategy

With an IP and with the understanding of the need and/or desire to develop a product-led business, entrepreneurs are then faced with the quest to better understand the target market, and how to get the product to that market; as some entrepreneurs put it: “who is going to use [our product]?” (CEO of Finance-Software), or “where can [our product] be used?” (CEO of Tool-Software); hence, the issue of market legitimacy arises. Market legitimacy is about conveying to stakeholders that the INV has the market-related capabilities to operate effectively in its industry [42]. According to the data, in order to acquire market legitimacy, entrepreneurs may bring in non-executives, and/or advisors with rich experience in marketing and sales to serve on the board or as marketing or sales operating officers:

“We had experience in selling our consulting services, backed up by our technical credibility; selling a product was a completely different thing. We did not have any background in that; that is why we looked for a non-exec in that particular area; someone who actually sold products worldwide.”—CEO of Project-Software

“Getting advisors on board helps companies to get the money; but partly would be to fill in the expertise gaps; also they would be called in to demonstrate a kind of endorsement: the bigger the name of the adviser, the bigger the impression they would make on VCs, kind of window dressing if you like.”—Business Strategy Consultant

At the same time, entrepreneurs engage large consulting companies or strategic advisors with intimate knowledge of the local investor community to aid them in the process of fund raising. The acquisition of venture capital, hence the presence of a VC or VC syndicate on the board, enhances the INV market legitimacy. Grounded in data, there also emerged the referral from powerful enterprises as a means to endorse the INV and its innovation.

“The key to raising venture capital money is to make sure you bring people on board who actually help the company. I liked working with investors and when we opened the office in the US we got all the support we could get.”—CEO of Data-Software

“The key things that make people buy, particularly in B2B market, are if they can refer to somebody else who’s bought from you, and that reference would normally be within the same sector.”—CEO of Finance-Software

“We signed up [a large consulting company] to assist us in raising funds from three venture capitalists. We also have as a sales and marketing director the former vice-president of sales of a large enterprise player, and, as a chairman, the former general manager of another large enterprise player.”—CEO of Mobile-Software

The data further point to external factors that are beyond an entrepreneur’s control, but which contribute to market legitimation, for example, regulative or normative pressures [50]. To illustrate, an opportunity might be regulatory driven, rather than economically driven when increased regulation in the financial sector forces financial institutions to continuously adopt e- and internet-based solutions for their businesses; as one of the interviewees put it:

“There are two ways to make a donkey to move, i.e., either to flutter an herb in front of it or hit it with a stick from the back… We found that stick and it worked.”—Marketing Director of Finance-Software

The findings also reveal several challenges that await entrepreneurs in the pursuit of market legitimacy, especially when non-execs, advisors, or investors are sought and later brought on board. The most challenging for an entrepreneur is to sell his or her idea to new business partners, and to justify the best course of action as perceived by the entrepreneur. This is due to the fact that decisions related to starting an INV, or investing in such a venture, were made under conditions of technology and market uncertainty, that is, when the possible outcomes of such decisions and the probability of those outcomes were unknown [23], and market signals were not reliable [24,25,26]. Such uncertain decision-making settings have a snowball, most of the time negative, effect on the process of developing congruence between entrepreneurs’ and new business partners’ goals [51]. This is how entrepreneurs described their experiences in the pursuit of market legitimacy: gut feeling, loss of control, loss of agility, stifle the growth, imposed their agenda [of rapid internationalization] on us, possible collision between advisors and investors, to name a few.

4.3. Operating Legitimation Strategy

To mitigate this kind of challenges, the data suggest that entrepreneurs should turn their attention to the acquisition of operating legitimacy. Through operating legitimacy, entrepreneurs aim to convey to their stakeholders that the INV has, given the circumstances, an optimal organizational gestalt, which consists of mutually supportive organizational system elements combined with appropriate resources and behavioral patterns [52]. This might be the toughest legitimation strategy to acquire for the high-technology entrepreneurs; as the liquidator explained:

“Technology businesses might be very good at generating sales, but a lot of them are not; a lot of them are operating on the expectations for the future; and what they do is they create a structure that in my view is too ambitious; it is ahead of itself in terms of the maturity of the business. In some ways entrepreneurs are a lot more amateur in their management style. They can be extremely naïve about how they have to deal with their new ventures.”

In the process of acquiring operating legitimacy, entrepreneurs are concerned, inter alia, with establishing an office, hiring employees, developing internal policies and operating procedures, developing incentive mechanisms to stimulate efficiency, attracting customers and generating first sales, as well as getting business and management education – all these being a new realm for most entrepreneurs as the quotes below illustrate:

“We felt there was a need to establish more of a real company; we had to hire full time development staff, establish an office. The fact that we had to hire staff brought all these issues of how to motivate staff: we got the best out of them, treated them properly, and did all the things you have to do professionally to have staff; and taking on board the office and other additional overheads.”—CEO of Project-Software

“For our employees that was not a difficult transition; it was something that they grew up with to some extent from universities when this technology started to emerge… We had a profit scheme where we shared some of our profits with all the staff. What we started thinking about was how we could actually develop a market focused proposition... Changing in thinking was also promoted in some way by two of the key executives by getting an MBA.”—CEO of Finance-Software

“I often wondered whether we went to too many markets. Customer base was very important; product was quite important, because while we were building our own platform, we could still deploy their existing products; it meant that we had revenues; so acquiring customer base was good; acquiring the legacy product was good; and the knowledge of customer needs; the development skills were not good; and actually their sales, in terms of scale were not good.”—CEO of Mobile-Software

“We raised more money than we actually needed… I think if we had fewer resources, we would have made better decisions. The pressure was to invest it and the objective was not to do it as cheaply as possible; but to move as quickly as possible... As a relatively new company, when recruiting so many people so quickly and in so many different parts, you have to make sure that everybody understood the vision of what we were trying to accomplish. It was also quite difficult when your customers are in US, but your product development team was back in UK.”—CEO of Data-Software

The emergent nature of the market an INV operates in makes the acquisition of operational legitimacy more imperative (quadrant I, Figure 1), and more challenging. In such uncertain decision-making settings, values and norms, and binding expectations are also in the process of emergence, and entrepreneurs and their key stakeholders (e.g., VCs) learn as they go. Moreover, such an emerging environment dominated by information asymmetry is conducive to mistrust and goal misalignment between entrepreneurs and VCs [51]. Having the right management team becomes critical to the success of the venture, as the venture capitalist reiterated:

“In the round one VCs are looking for pre-product; round two is the product, and some reference customers; round three is you’ve got revenue of millions of pounds. If you have pre-product, pre-customer and your management is weak, you won’t get a funding. VCs need an excellent management team when there is no product or customers.”

4.4. Locational Legitimation Strategy

Through locational strategy entrepreneurs aim to achieve several legitimation objectives. One, by locating their offices abroad, entrepreneurs aim to overcome the disadvantage of foreignness [53] so that their ventures are perceived as a venture from a target market, e.g., an American company or a European player and/or as a venture that conforms to similar rules, norms and values [8], e.g., by locating in Silicon Valley, California or Silicon Glen, Scotland. As interviewed entrepreneurs explained:

“We opened an office in Silicon Valley so that we can make the company look like an American company to the American market. We also opened two other in different US locations; now we’re just two miles away from our strategic partner.”—CEO of Data-Software

“To enter the enterprise market we had to be perceived as a European, not UK player. And we designed the company that way from day one.”—CEO of Mobile-Software

“One of the keys to the enterprise market was that it was very much populated by very big players so we had to look big.”—Marketing director of Finance-Software

Two, by locating abroad or at least by explicitly stating their intentions to locate abroad, entrepreneurs send a signal to prospective investors that a venture has a potential for very high gains in combination with the availability of early exit strategies. At the end of the day, by locating abroad, entrepreneurs increase the likelihood of receiving venture funding; as one VC explained it:

“Businesses that we typically backed are businesses which need to sell internationally. We will not typically back a business if it is not addressing the world market.”

4.5. Alliance Legitimation Strategy

Alliance legitimation strategy emerged as a paradox, with conflicting findings. On one side, the findings are consistent with those from the literature, whereby INVs mitigate the risk of newness by entering international cooperative agreements, partnerships, and joint-ventures [54] with larger, well-established companies, with the aim of increasing their visibility, reputation, image, and prestige [55,56,57,58]. Such business connections with large firms are likely to mitigate the liability of outsidership [59] and eventually increase the probability of attaining the legitimacy threshold [60] as the quotes below show:

“The funny thing is that nothing was actually signed with [our strategic partner]; it was almost a gentlemen’s agreement. Wanting to go ahead of the game, they were trying to adopt and launch additional SIM capability and they needed tools to test it on mobile phones.”—CEO of Tool-Software

“The goal really was to find out partners that could help us to break into the US. Because we had fairly new technology, we tried to get some help from some of the big enterprise players, like Microsoft, and Oracle. We talked to some of them, and decided to partner with [our strategic partner] with whom we had more tractions than we did with [the other]; we felt we could co-exist alongside [our strategic partner].”—CEO of Data-Software

“Ultimately to really get the product somewhere you have to sell it through a US company; we sell now to a large defense company; we have a good image, even perceived by our clients as a big company.”—CEO of Project-Software

“We wanted to go into enterprise space; we needed a bit of track record and credibility. We had to get into some relationships with a big player.”—Marketing director of Finance-Software

“We could’ve done more to develop relationships with [our strategic partner]; but if we succeeded, we would’ve been just swallowed up, or kicked in one side. So, we could not have grown the business to the extent that we wanted to independently. It was a tradeoff.”—CEO of Mobile-Software

On the other side, the data point to the opposite effect that the alliance legitimation strategy has on the process of international new venture legitimation. For example, what entrepreneurs discovered was that large enterprise players demand exclusive partnerships, thus making them captive to such relationships, with no practicable alternative but to sell their products via a single enterprise player [35]. This effect questions Johanson and Vahlne’s ([59], p. 1411) conjecture that “… insidership in relevant network(s) is necessary for successful internationalization”. This is how entrepreneurs described such (insidership) relationships: spooking, lot of clouds, seriously bad company, bandits, and Venus flytrap.

4.6. Anchoring Legitimation Strategy

Anchoring as a type of legitimation strategy emerged later in the coding process. Initially, during the process of open coding, hype as In Vivo code was used to conceptualize this kind of behavior, as the following quotes demonstrate:

“When I look at the business plan at forecasts to get the initial funding, I can say straight away: this is ridiculous, absolutely ridiculous, there is no way the company could grow at that pace… The whole trust… if a young technology business is to create large expectations about sales and profits levels, it is kind of hyping and this is how entrepreneurs generate VC money.”—Liquidator

“The hype is important as it creates fashion; hype is driven by fashion. If you like, hype and fashion are the two sides of the same coin. So, if everyone is doing what is fashionable, then by definition, everybody is doing it. The hype releases the investment decisions because they reduce the pain of failure.”—Strategic advisor

Going back to the literature helped identify anchoring as a theoretical code [20]. Anchoring is viewed as being one of the strongest and most prevalent of cognitive biases [46]. It refers to a situation in which decision makers, under organizational pressures, and when forecasts are critical in attracting funding, have big incentives to accentuate the positive and downplay the negative in laying out prospective outcomes [46]. Entrepreneurs, in the attempt to attain a legitimacy threshold, may tell “legitimacy lies that are intentional misrepresentations of the facts” ([61], p. 950). Such cognitive bias is amplified under uncertain decision-making settings that are largely characterized, inter alia, by the asymmetry of information, as the following quotes exemplify:

“We always felt it was very important to build up our brand. So, we kind of played the press game. To get into papers, you have to give them something. And therefore, you tend to, I would say, make up things; you have to exaggerate things... It is like building people’s expectations.”– CEO of Finance-Software

“Our business plan was a bit ambitious, not to say the least, is the reality of it. We knew it was a bit ambitious as well, but you have to pitch in that fashion in order to secure any investment at all. VCs themselves encouraged this approach and this type of statements.”—CEO of Project-Software

“…the second round funding will support our rapid expansion in a sector currently valued at $10 billion; however, it is estimated that by 2003 the sector will be worth $150bn… Hype, for us, was about timing. At a time people were grossly exaggerating things.”—CEO of Data-Software

“We had to construct the business plan that would give the investors the rates of return to buy them into; so, we had to construct something that would say that we could do it for 15 million. And in the hindsight, that may not have been the best way of going about it.”—CEO of Mobile-Software

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This study explored in depth how INVs acquire legitimacy during the process of their emergence. It employed critical incident technique in order to capture critical events that entrepreneurs faced during the legitimation process. Grounded in data, the study makes several contributions to INV legitimation theory on one hand, and to legitimation theory on the other. First, the study supports a number of legitimation strategies yielded by prior research, namely market, locational, and alliance legitimation strategies. At the same time, the study found no support for other legitimation strategies suggested by the extant literature, namely historical and scientific legitimation strategies [42]. This latter result should be treated with caution, since the sample selected for this study was confined to INVs in which the emergence of the international opportunity coincided with the emergence of a venture as a legal/operational entity. In other words, the legitimation process starts before or immediately after the inception of a new venture, that is, when an entrepreneur has identified and commenced the pursuit of a new (international) opportunity, and the new venture, for the most part, has neither internal nor external legitimacy. Should the focus of research have been on INVs from an intrapreneurship perspective, scientific and historical legitimation strategies would have played an important role in the process of INV legitimation along with the other legitimation strategies.

Second, the study further contributes to our understanding of INV legitimation by suggesting new types of legitimation strategies, mainly technology, operating, and anchoring. Technology legitimation strategy aims to validate an innovation or technology that has been created to meet a need or solve a problem, and targets large enterprise players on the assumption that they could become early adopters of that technology. Technology legitimation could be achieved by recruiting key technical or engineering personnel, via certification, and/or development of built-in capability [62]. The biggest challenge in the pursuit of this legitimacy is to find early adopters that are willing to try the new technology.

Through operating legitimacy, INVs aim to convey to their stakeholders, especially potential investors, that these ventures have optimal organizational gestalt, are efficient and professional. This could be achieved, inter alia, by registering a legal entity, establishing an office, hiring employees, developing internal policy and operating procedures (including incentives mechanisms), fostering business education among entrepreneur-owners and top management, and completing a business plan [9]. Given that these INVs emerge in an uncertain environment (quadrant I, Figure 1), the key challenge entrepreneurs face in this endeavor is to set up and commit to long-term outcome goals, respectively, and to develop performance benchmarks that, however, may lead to goal misalignment between entrepreneurs and their backers [51,63]. Entrepreneurs may mitigate such issues in uncertain decision-making settings by developing and pursuing just procedures that are valued by VCs and other key stakeholders that are associated with long-term venture performance [64,65].

Anchoring legitimation strategy aims to increase the likelihood of attracting venture funding and other resources by intentionally misrepresenting the facts about the INV potential. In an uncertain decision-making setting, asymmetry of information is created as entrepreneurs are the only ones who posse intimate knowledge about the technology or INV potential. Anchoring legitimation strategy could be achieved by hyping the business plan, accentuating the positive while downplaying the negative [46], stretching the rules [66], or telling legitimacy lies [61]. In addition to the risk of getting less funding as stakeholders learn more about the INV potential, there is an ethical issue associated with this legitimation strategy. From the legitimation theory perspective, the findings related to the anchoring legitimation strategy raise interesting research questions, for example, do ethical considerations or stretching the rules moderate the process of legitimation or do they set the (ethical) boundaries of the legitimation theory?

As this study was concerned with INV legitimation in emerging industries (quadrant I, Figure 1), it is conjectured that these legitimation strategies are time dependent. That is, with elapsed time and with growing experience and knowledge, INVs and industries they operate in transition from an uncertain decision-making setting (quadrant I, Figure 1) to a risk decision-making setting (quadrant II, Figure 1). In other words, the main sources of uncertainty, such as technical uncertainty, market uncertainty, and goal ambiguity, fade away or are lessened with elapsed time, as the following quote from a VC exemplifies:

“…the market was extremely bullish, and investors were willing to take very large risks; also, we had an inflated idea of what companies might be worth. The big thing that we’ve been working on quite hard to improve was to get the views on the size and trends of the markets. For example, in [the] case of Project-Software, we did not have that level of information and found out the market was actually much smaller than we thought.”

Following from the above, uncertainty could be seen as a boundary-determining criterion [21,67] of INV legitimation that emerged as a dynamic, at times belligerently so, non-linear process (Table 3). Following Dubin ([21], p. 96), who argues that “… empirically relevant theory in the behavioral and social sciences is built upon the acceptance of the notion of relationship rather than of the notion of causality”, future theory-building research is suggested to improve our understanding of relationship between the legitimation strategies and then to seek to improve prediction.

Third, the study makes an attempt to further our understanding of the legitimacy threshold concept that extant literature refers to as a tipping point [68], or a certain ceiling [22], or as a made it feeling [60] at which the INV can achieve further gains in legitimacy and resources [6], or at which legitimacy is no longer an issue, with competition being the primary concern [22]. The actual lack of extant research on legitimacy threshold may suggest that it is an elusive phenomenon that “… exists [but] … is difficult to identify and probably unique to each new venture” ([6], p. 428).

The findings that emerged in this study in relation to legitimation strategies suggest several pointers for future scholarly discussion about, and research on, the legitimacy threshold. The study findings suggest that the legitimacy threshold is rather a summative unit of the legitimation theory, a unit that draws “… together a number of different properties of a thing” and has “the property that derives from the interaction among a number of other properties” ([21], p. 66). The proposed view on the summative unit of the theory of legitimation builds on the assumption that legitimacy is continuously constructed and reconstructed in an attempt to maintain an alignment with the changing institutional environment [69]. It is, thus, conjectured that the legitimacy threshold emerges as a result of interaction among a number of legitimation strategies, seen as an effect of several tipping points, e.g., the technology legitimacy threshold, market legitimacy threshold, or operating legitimacy threshold. From the latter conjecture it follows that the legitimacy threshold is a process rather a clear-cut dichotomous phenomenon. It may further be argued that, during this process, critical events play an important role as they contribute to the acquisition of a certain type of legitimacy, be it technology, operating, or alliance legitimacy. The above inferences clearly will have an impact on the way the levels and units of analysis are defined in an attempt to empirically investigate the process of the emergence of the legitimacy threshold. For example, cross sectional or longitudinal research may be conducted across and/or within various types of legitimation strategies.

Fourth, the study, in the tradition of contextualizing theory-building research [70], delineates the domain of scholarly research on legitimation (Figure 1) and positions within it the research on INVs (quadrants I and II, Figure 1). This intersection between legitimation theory and INV theory opens up a promising research agenda. For example, researchers may explore not only how and why INVs acquire legitimacy, but also how INVs contribute to the creation and legitimation of the new, emerging sector of an economy (quadrant I) or how INVs change and shape the legitimation of an existing sector of an economy (quadrant II).

Researchers may delve into how INVs transition from one quadrant to another. Here the velocities with which INVs and markets emerge play an important role. For example, if an INV legitimates faster than the market it operates in, a longitudinal research would observe that INV moving from quadrant I to quadrant IV would be primarily concerned, for example, with how to defend its legitimacy in an attempt to contribute to further legitimation of the industry it operates in, to de-legitimize, or leave that market. If a new sector legitimates faster than an INV from that sector, then, from quadrant I, the INV will move to quadrant II where it should instead continue its legitimation efforts in the risk decision-making setting that distinguishes quadrant II from quadrant I.

Concurrent legitimation of an INV and the sector it operates in will allow researchers to observe how INVs move from quadrant I to quadrant III where INVs will be concerned with maintaining their legitimacy and/or defending it against newcomers. By mapping various INVs (e.g., low tech vs. high tech, or from developed countries vs. from emerging countries) onto Figure 1, researchers could develop theory about different trajectories that INVs may follow in their attempts to legitimize. This would allow researchers and practitioners to delve deeper into how each type of legitimation strategy operates. Researchers may also study how established international ventures further create and legitimate their products or services in international (emergent) markets, or even how new industries or sectors of an economy are created. Mapping INVs onto Figure 1 would also allow international entrepreneurship researchers develop much needed contextualized definitions of INVs [71].

Given the case study nature of the study, which is based on a small number of observations, the above-identified directions for future research at the intersection of legitimation theory and INV emerging theory would further our understanding of the INV legitimation process. Studying INVs through the theoretical lenses of legitimation is a promising area of research that would contribute to the advancement of international entrepreneurship theory.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Fan, T.; Phan, P. International new ventures: Revisiting the influences behind the ‘born-global’ firm. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2007, 38, 1113–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S. The theory of international new ventures: A decade of research. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2005, 36, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinchcombe, A. Social Structure and Organizations. In Handbook of Organizations; March, J., Ed.; Rand McNally: Chicago, IL, USA, 1965; pp. 142–193. [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich, H.; Fiol, C. Fools rush in? The institutional context of industry creation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1994, 19, 645–670. [Google Scholar]

- Zaheer, S. Overcoming the liability of foreignness. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 341–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, M.; Zeitz, G. Beyond survival: Achieving new venture growth by building legitimacy. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 414–431. [Google Scholar]

- Drori, I.; Honig, B.; Sheaffer, Z. The life cycle of an internet firm: Scripts, legitimacy, and identity. Ent. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 715–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, M. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar]

- Delmar, F.; Shane, S. Legitimating first: Organizing activities and the survival of new ventures. J. Bus. Ventur. 2004, 19, 385–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rialp, A.; Rialp, J.; Knight, G. The phenomenon of early internationalizing firms: What do we know after a decade (1993–2003) of scientific inquiry? Int. Bus. Rev. 2005, 14, 147–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, J.; Sadrieh, F.; Annavarjula, M. Two decades of international entrepreneurship research: What have we learned—where do we go from here? Int. J. Ent. 2009, 13, 23–64. [Google Scholar]

- Keupp, M.; Gassmann, O. The past and the future of international entrepreneurship: A review and suggestions for developing the field. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 600–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.; Coviello, N.; Tang, Y. International entrepreneurship research (1989–2009): A domain ontology and thematic analysis. J. Bus. Ventur. 2011, 26, 632–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S. State-of-the-art current research in international entrepreneurship: A citation analysis. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 5, 1020–1038. [Google Scholar]

- Dyer, G.; Wilkins, A. Better stories, not better constructs, to generate better theory: A rejoinder to Eisenhardt. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 613–619. [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan, J. The critical incident technique. Psychol. Bull. 1954, 51, 327–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chell, E. Critical Incident Technique. In Qualitative Methods and Analysis in Organizational Research: A Practical Guide; Symon, G., Cassell, C., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 1998; pp. 51–72. [Google Scholar]

- Butterfield, L.; Borgen, W.; Amundson, N.; Maglio, A.-S. Fifty years of the critical incident technique: 1954–2004 and beyond. Qual. Res. 2005, 5, 475–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edvardsson, B. Service breakdowns: A study of critical incidents in an airline. Int. J. Ser. Ind. Manag. 1992, 3, 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B. Theoretical Sensitivity; Sociology Press: Mill Valley, CA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Dubin, R. Theory Development; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, C.; Dowd, T.; Ridgeway, C. Legitimacy as a social process. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2006, 32, 53–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, S.; Barney, J. How do entrepreneurs organize firms under conditions of uncertainty? J. Manag. 2005, 31, 776–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coltman, T.; Devinney, T.; Latukefu, A.; Midgley, D. E-business: Revolution, evolution, or hype. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2001, 44, 57–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). The New Economy: Beyond the Hype; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Turcan, R.V. Toward a theory of international new venture survivability. J. Int. Ent. 2011, 9, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dholakia, N.; Turcan, R.V. Bubbles: Towards a typology. Foresight 2013, 15, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitektine, A. Legitimacy-based entry deterrence in inter-population competition. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2008, 11, 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, C. The antecedents of deinstitutionalization. Org. Stud. 1992, 13, 563–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassanini, A.; Scarpetta, S. Growth, technological change, and ICT diffusion: Recent evidence from OECD countries. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2002, 18, 324–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilat, D. Digital economy: Going for growth. OECD Obs. 2003, 237, 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Booz-Allen & Hamilton. Competing in the Digital Age: How the Internet will Transform Global Business; EIU: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Turcan, R.V.; Fraser, N.M. The Emergence of an International New Software Venture from an Emerging Economy. In Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing: Software Business: Third International Conference; Cusumano, M., Iyer, B., Venkatraman, N., Eds.; Springer Publishing Company: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 114–127. [Google Scholar]

- Groen, A.; Wakkee, I.; Weerd-Nederhof, P. Managing tensions in a high-tech start-up: An innovation journey in social system perspective. Int. Small Bus. J. 2006, 26, 57–81. [Google Scholar]

- Turcan, R.V. External legitimation in international new ventures: Toward the typology of captivity. Int. J. Ent. Small Bus. 2012, 15, 262–283. [Google Scholar]

- Turcan, R.V.; Marinova, S.T.; Rana, M.B. Empirical studies on legitimation strategies: A case for international business research extension: Institutional theory in international business and management. Adv. Int. Manag. 2012, 25, 425–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornikoski, E.; Newbert, S. Exploring the determinants of organizational emergence: A legitimacy perspective. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 311–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zott, C.; Huy, Q. How entrepreneurs use symbolic management to acquire resources. Adm. Sci. Q. 2007, 52, 70–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargadon, B.; Douglas, Y. When innovations meet institutions: Edison and the design of the electric light. Adm. Sci. Q. 2001, 46, 476–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, N.C.; Stokes, D. Laments and serenades: Relationship marketing and legitimation strategies for the cultural entrepreneur. Qual. Market Res. 2004, 7, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.W.; Xu, D. Growth and survival of international joint ventures: An external-internal legitimacy perspective. J. Manag. 2006, 32, 426–448. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, R.S.; Chandy, R.; Prabhu, J. The fruits of legitimacy: Why some new ventures gain more from innovation than others. J. Mark. 2008, 72, 58–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.E.; Pennings, J.M. Innovation and strategic renewal in mature markets: A study of the tennis racket industry. Org. Sci. 2009, 20, 368–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidsson, P.; Hunter, E.; Klofsten, M. Institutional forces: The invisible hand that shapes venture ideas? Int. Small Bus. J. 2006, 24, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, D.; Voronov, M. Toward a practice perspective of entrepreneurship: Entrepreneurial legitimacy as habitus. Int. Small Bus. J. 2009, 27, 395–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovallo, D.; Kahneman, D. Delusions of success: How optimism undermines executives’ decisions. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2003, 81, 56–73. [Google Scholar]

- Storey, D. Understanding the Small Business Sector; Routledge: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.; Huberman, M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook; Sage: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Weick, K. Theory construction as disciplined imagination. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 516–531. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, W. Institutions and Organizations; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Turcan, R.V. Entrepreneur-venture capitalist relationships: Mitigating post-investment dyadic tensions. Ventur. Cap: Int. J. Entr. Financ. 2008, 10, 281–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slevin, D.; Covin, J. Time, growth, complexity, and transitions: Entrepreneurial challenges for the future. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1997, 22, 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Cuervo-Cazurra, A.; Maloney, M.; Manrakhan, S. Causes of the difficulties in internationalization. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2007, 38, 709–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviatt, B.; McDougall, P. Toward a theory of international new ventures. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2004, 24, 45–64. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, S.; Barney, J. How entrepreneurial firms can benefit from alliances with large partners. Acad. Manag. Exec. 2001, 15, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barringer, B.; Harrison, J. Walking a tightrope: Creating value through interorganizational relationships. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 367–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, M.; Grilli, L.; Murtinu, S.; Piscitello, L.; Piva, E. Effects of international R&D alliances on performance of high-tech start-ups: A longitudinal analysis. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2009, 3, 346–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lounsbury, M.; Glynn, M. Cultural entrepreneurship: Stories, legitimacy, and the acquisitions of resources. Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 545–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, J.; Vahlne, J.-E. The Uppsala internationalization process model revisited: From liability of foreignness to liability of outsidership. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2009, 40, 1411–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutherford, M.; Buller, P. Searching for the legitimacy threshold. J. Manag. Inquiry 2009, 16, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutherford, M.; Buller, P.; Stebbins, J. Ethical considerations of the legitimacy lie. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 949–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E.; George, G.; Alexy, O. International entrepreneurship and capability development—qualitative evidence and future research directions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2010, 35, 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.; Latham, G. A Theory of Goal Setting and Task Performance; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Sapienza, H.; Korsgaard, M. The role of procedural justice in entrepreneur—venture capital relations. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 544–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busenitz, L.; Fiet, J.; Moesel, D. Reconsidering the venture capitalists’ value added proposition: An interorganizational learning perspective. J. Bus. Ventur. 2004, 19, 787–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuemmerle, W. A test for the fainthearted. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2002, 80, 122–127. [Google Scholar]

- Merton, R. Social Theory and Social Structure; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, P.; Powell, W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 47–160. [Google Scholar]

- Suddaby, R.; Greenwood, R. Rhetorical strategies of legitimacy. Adm. Sci. Q. 2005, 50, 35–67. [Google Scholar]

- Zhara, S. Contextualizing theory building in entrepreneurship research. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesinger, B.; Fink, M.; Madsen, T.; Kraus, S. Rapidly internationalizing ventures: How definitions can bridge the gap across contexts. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 1816–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Appendix. Critical Event Charts of Case Companies

Finance-Software

| Year | QI | QII | QIII | QIV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | Management buy-out of an R&D lab of multinational company | |||

| Internationalized instantly (USA, Brazil, Europe) | ||||

| 1998 | Realized they were operating without any focus; had incurred losses | Decided to focus on new, emerging technology | ||

| Identified the need to diversify and deliver tangible product | Trained staff in that new technology | |||

| Re-engineered the work for its parent company in this new technology | ||||

| 1999 | Decided to focus 100% on domestic financial services sector | Became authorized [new technology] development centre | ||

| Partnered with [MNE] to enter the financial service market | ||||

| 2000 | IT market in the US started to collapse | |||

| 2001 | Opened 3 offices throughout UK | IT market started worsening in the UK | Launched the 1st version of the product | |

| Announced as the fasted growing company of the year | ||||

| 2002 | Was still bullish about its growth | Forced to cut one sixth of staff | ||

| 2003 | Discovered that the product is 'at least 12 months to soon to the market' | Decided to 'cocoon' | ||

| Downsizing continued | Retained the IP and key personnel | |||

| Waits for the market to pick up |

Project-Software

| Year | QI | QII | QIII | QIV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 | Started-up as a consulting company | |||

| 1994 | Identified new market opportunity to diversify and deliver tangible product | |||

| 1995 | Started R&D activities | |||

| 1997 | Launched 1st version of the product via a deal with OEM | |||

| 1998 | Deal with OEM failed | Pitched to VCs to raise funds to market the product in UK | Changed the business plan as per VCs request [to market to US] | |

| 1999 | Received 1st round of funding | Had to agree with VCs on entering the European market | Initiated international expansion into Europe and the US | |

| Hired a marketing non-exec from the OEM they had deal with | Established a relationship with a master distributor to enter European market | |||

| 2000 | Started exporting the product to the US and Europe | IT market in the US started to collapse | Received 2nd round of funding | Marketing non-exec stepped down |

| Continued exporting efforts and making trips to the US | Continued exporting efforts and making trips to the US | Continued exporting efforts and making trips to the US | ||

| Abandoned hopes for Europe as no sales were realized | VCs appointed their own non-exec specializing in crisis management | |||

| 2001 | Signed in the US a joint-venture deal with a UK MNE that had a large US customer base | IT market started worsening in the UK Presented to VCs the plan to 'cocoon' | Bank reconsidered its position and offered new terms and conditions | Resurrected: registered as new company |

| Developed a 'dramatic plan to improve things' to be presented to VCs | The plan to 'cocoon' was accepted by all but one investor, the bank of the company | Decided that 'the game was over' | Bought over the IP from the liquidator, re-employed senior software engineer | |

| Were introduced to a liquidator in case the 'dramatic' plan is not backed up by VCs | Approached the liquidator to surrender | Was liquidated | Re-branded the software, launched its 1st version | |

| Re-internationalised |

Tool-Software

| Year | QI | QII | QIII | QIV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1985 | Started-up as a service-based company | |||

| 1991 | Won a project to develop a smart-card test application | |||

| Decided to develop that application into a tool | ||||

| 1992 | Reached a "gentlemen's agreement" with a large telecom operator to develop a test tool for mobile phones smart-cards | |||

| 1993 | Released its first version of the tool | Launched 1st version of the product via a deal with OEM | ||

| Took its first version of the tool to Europe | ||||

| 1994 | Tried to raise venture capital, but with no success | |||

| 1995 | Smart-card technology started being adopted globally | Took its products to the US | Moved to profitability | |

| 1999 | Opened its first overseas office in the US | Won a strategic contract with one of the largest software player in the world | ||

| 2000 | Recession of the IT market | That large software player withdrew from the smart-card market, and from that strategic partnership | The opportunity that was identified was not realizing | Laid-off half of its staff, and restructured its overseas offices |

| Grew out of the tool market | Decided to focus back on 2G tools and services business to generate tactical revenue | |||

| Spotted new opportunity to develop a 3G smart-card platform for telecom and finance sectors | ||||

| Received its first round of funding to develop the platform | ||||

| 2001 | Received its second round of funding | Opened its second overseas office: Japan | ||

| 2002 | Received its third round of funding | |||

| 2003 | Had ~ 220 customers in 33 countries | Released the platform |

Mobile-Software

| Year | QI | QII | QIII | QIV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | Market opportunity identified | IT market in the US started to collapse | Started-up | Started the fund raising process |

| Internationalized instantly via acquisitions (Europe, UK, Midle East) | Hyped' the business plan to 'buy the investors into' | |||