Abstract

As sustainability and Corporate Social Responsibility gained increasing importance in agriculture, several impact assessment methodologies have been proposed. Social Return on Investment (SROI), a methodology used for understanding, measuring, and reporting the social, economic, and environmental value created by an organization, emerged as a promising approach to quantify and monetize social and environmental impacts. However, research on SROI application within the wine industry remains limited, despite the sector’s global relevance and unique economic, social, and cultural dimensions. This study addresses this gap by evaluating the potential and limitations of SROI in assessing the social impact of a wine cellar’s products, services, and activities on its stakeholders. Indeed, we find confirmation that, as in other sectors, this methodology can support sustainability reporting and strategic decision-making. Applying the SROI methodology, stakeholder outcomes were analyzed, and the results indicate that for every EUR 1 invested, approximately EUR 1.44 of social value is generated, demonstrating SROI’s effectiveness in capturing social contributions beyond financial metrics. This study highlights SROI’s advantages, while also acknowledging challenges. Findings suggest that, despite some limitations, SROI can enhance wineries’ sustainability strategies and offers a robust framework to guide wineries—and potentially other agricultural sectors—toward socially responsible and sustainable practices. Future research should focus on developing industry-specific proxies and integrating SROI with other sustainability assessment tools, particularly in support of ESG reporting. This study contributes to academic discourse on impact evaluation methodologies and provides practical implications that aim to balance economic performance with social responsibility.

1. Introduction

During recent years, citizens have been increasingly concerned about the social and environmental impact generated by companies (Wekesa, 2024; Deep, 2023; Hsu & Bui, 2022). Specifically, they are becoming more conscious and see the act of consuming as not only a financial transaction, but an interaction in which personal principles increasingly influence consumption choices (Duarte et al., 2024).

Thus, today’s consumers have integrated sustainable, environmental, and social considerations into their lifestyle choices (Phan-Le et al., 2024), which are based not only on the satisfaction of their needs but also on how these products affect society and the environment on a global scale (Kour, 2024; Johnston et al., 2001), affecting inequality and climate change (White et al., 2019; Ashenfelter & Storchmann, 2016; Dumre et al., 2025).

Hence, impact assessment has become a crucial process for firms, defined as the process of identifying and evaluating the effects of an intervention on the factors or objectives that the intervention is designed to affect (Kirkpatrick, 2002).

Specifically, impact assessment is relevant to evaluate the substantive intervention of firms that contribute along the three dimensions of economic, social, and environmental value creation (Trautwein, 2021; Haski-Leventhal & Mehra, 2016; Matsali et al., 2025) and bring longer-term changes in social, technical, or natural systems (Fichter et al., 2023; Dijkstra-Silva et al., 2022). In particular, social impact is generally referred to as the process of analyzing, monitoring, and managing the intended and unintended social consequences, both positive and negative, of planned interventions such as policies, programs, plans, and projects, with the primary purpose to bring about a more sustainable and equitable human and social environment (Vanclay, 2003).

In order to overcome the imperfection of accounting solely for the strictly financial results of companies, several methodologies have been developed for measuring and accounting for this broader concept of value (Vanclay, 2006; Gionfriddo & Piccaluga, 2024). Among these, the Social Return On Investment (SROI) has internationally emerged as a viable approach to measure the extent to which social impacts are being achieved (Cagarman et al., 2023).

SROI is an impact evaluation technique explicitly designed to include social and environmental effects in the assessment of an organization’s activities (Corvo et al., 2022). Also, this technique offers a standardized methodology that allows for the collection of relevant impact data with a low administrative burden (Cagarman et al., 2023).

Through SROI, the generated impact can be measured as a collective value reflecting the economic, social, and environmental impacts, with positive impacts referred to as benefits and negative impacts as costs (Yates & Marra, 2017). It captures the economic value of social and environmental outcomes by translating qualitative objectives into financial measures and focuses on the most important sources of value as defined by stakeholders (Maier et al., 2015). This type of analysis helps organizations understand and manage the social, environmental, and economic value that they create (Maldonado & Corbey, 2016).

Even though some articles have examined the application of the SROI methodology to agricultural and farming practices (Basset, 2023) and the existing literature about this field of research will be presented in the following sections, there is still a research gap about the functionality and distinctiveness of the application of the SROI methodology to evaluate the effects of specific agricultural sectors. In particular, its applicability to wine cellar products, services, and activities on its stakeholders, i.e., clients, service users, suppliers, and employees, has not yet been evaluated. The evaluation of the SROI applicability in this field addresses this gap and is particularly relevant since it provides wineries with a structured tool to quantify and communicate their societal value creation, enabling them to align sustainability initiatives with stakeholder expectations and regulatory reporting needs.

As one of the oldest activities, wine production has a high relevance in the economic, cultural, social, and environmental dynamics in several regions worldwide, particularly across Italy, which is a global leader in wine production (Bandinelli et al., 2020). Several factors contribute to Italy’s success: a millennia-long winemaking tradition, a wide diversity of grape varieties, quality-oriented vinification techniques, and a favorable climate and terrain conditions (Pomarici et al., 2021). The global wine industry plays a crucial role in both economic and cultural contexts, with a market valued at over USD 350 billion worldwide (Roma Business School, 2024). Italy, as a leading producer and exporter of wine, holds a significant position in shaping sustainable practices within the sector (Pomarici et al., 2021). Indeed, the Italian wine industry is not only central to the country’s economic structure but also deeply intertwined with its cultural heritage and environmental stewardship (Conto et al., 2014), aligning closely with the multidimensional focus of the SROI methodology. By focusing on the Italian context, this study aims to provide insights that are both locally grounded and transferable to other wine-producing regions seeking to align sustainability practices with comprehensive impact assessment.

Today, the wine industry has a leading role in the development of production practices that aim to minimize environmental impact (Guerra et al., 2024; Nunes & Loureiro, 2016). The growing awareness among consumers of the negative effects that traditional cultivation practices have on both human and environmental health (Valdelomar-Muñoz & Murgado-Armenteros, 2024) has led to increased demand for natural products, which are safer for the environment (Marozzo et al., 2024).

Sustainability in wine production, however, is not limited to environmental impacts (Baiano, 2021), and consumers have embraced a wider definition of sustainability, demanding supply chain transparency and evidence of strong social performance from companies (Wagner et al., 2023; Lovrinčević et al., 2025). In addition, due to its distinctive characteristics, the wine industry can serve as a reference point for other agricultural industries that aim to integrate sustainability into their business models.

Therefore, the research aims to answer the following research questions:

- RQ1: What are the main impact evaluation frameworks (e.g., SROI, etc.) and other sustainability practices adopted by Italian wineries?

- RQ2: What are the potential and limitations of SROI when evaluating the effects of a winery’s products, services, and activities on its stakeholders?

In order to answer these research questions, this article presents an analysis of the current state of the impact assessment and sustainability practices within the Italian wine industry, based on a questionnaire administered to a sample of 18 Italian wine cellars from various regions. Additionally, it includes a single case study of the Duca di Salaparuta wine cellar, located in Sicily, in which an impact assessment was conducted using the SROI methodology.

This paper is organized as follows. The next section provides a theoretical background by discussing the SROI framework and the existing literature on the application of SROI to agricultural and farming practices. The third section describes the analysis conducted on the overall situation of the Italian wine industry, in order to offer a comprehensive overview of the current landscape. The fourth section presents the SROI case study performed on the Duca di Salaparuta wine cellar. The analysis will document results and discuss the benefits that the organization has achieved from the SROI analysis. The fifth section discusses the findings and answers the research questions. The final section puts forward conclusions, outlines new research avenues, and identifies the limitations of this study.

2. Theoretical Framework and Literature Review

2.1. The Social Return on Investment

The Social Return on Investment is a framework used for understanding, measuring, and reporting the social, economic, and environmental values created by an organization (Gosselin et al., 2020) and it can be a valuable tool in demonstrating the financial and social value of enterprises, helping them attract investment and enhance credibility among stakeholders (Flockhart, 2005). The framework measures and accounts for a broad concept of value, not limited to the economic dimension, and seeks to reduce inequality and environmental degradation by incorporating social, environmental, and economic costs and benefits (Banke-Thomas et al., 2015).

SROI has a strong stakeholder orientation (Maier et al., 2015), where stakeholders are defined as those who experience change, whether positive or negative, as a result of the investment being analyzed. Thus, stakeholder engagement is crucial for identifying relevant outcomes and assigning value to them (Bux et al., 2024). Involving stakeholders can help the organization better understand the strengths and weaknesses of its activities, and may also provide useful information to support organizational improvement (Jonas et al., 2018).

As presented in the Guidelines for Social Return On Investment by Lingane and Olsen (2004), SROI uses monetization of social impacts in order to assess value. In particular, a monetary value is assigned to the qualitative changes generated, so that this value can be compared with the costs of required inputs, monetizing social benefits and costs. It captures the non-measurable impacts that a company creates and seeks to assess and quantify them. Therefore, it measures the significant intended and unintended outcomes of any organization and applies a monetary value to those outcomes.

In SROI, outcomes and investment amounts may be measured in non-monetary units, but all values in SROI should be conveyed in a common unit (Arvidson et al., 2013). This allows for the calculation of a benefits-to-costs ratio, which represents the final result of an SROI analysis: the ratio states how much social value (in EUR) is created for every EUR 1 of investment (Rotheroe & Richards, 2007). The SROI ratio is an estimate, not a precise figure: in order to estimate the value of the outcomes—including non-traded, non-market goods—SROI relies on financial approximations, known as proxies (Damtoft et al., 2023).

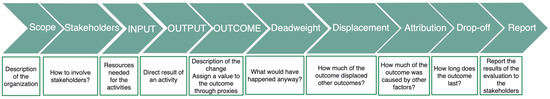

SROI analysis is the rigorous process of performing an SROI calculation. The approach is focused on attributing financial value to inputs and outputs, culminating in the calculation of the SROI ratio (Lingane & Olsen, 2004). Specifically, conducting an SROI analysis involves six stages (U.K. Social Value, 2012) (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

The SROI analysis process.

- Establishing scope and identifying key stakeholders: Before starting an SROI analysis, it is necessary to clarify what will be measured and what stakeholders will be involved;

- Mapping outcomes: This step involves developing an Impact Map, which shows the relationship between inputs (resources or activities), outputs (direct and tangible results from the activity), and outcomes (changes experienced by stakeholders as a result of the activity);

- Evidencing outcomes and assigning them a value: This stage involves valuing the mapped outcomes through indicators, which may be both qualitative and quantitative. Indicators clarify whether the outcome has occurred and to what extent. In an SROI analysis, financial proxies are used to estimate the social value of non-traded goods. This valuation process, often referred to as monetization, is considered a sensitive aspect of SROI, as all value is ultimately subjective. By estimating value through financial proxies and combining these valuations, an estimate of the total social value created by an intervention is obtained;

- Establishing impact: This step assesses whether the analyzed outcomes can be attributed to the organization’s activities or would have occurred regardless. Aspects of change that would have happened anyway or are the result of other factors are excluded from consideration. These are expressed as percentages and include deadweight, displacement, attribution, and drop-off. Establishing impact is essential to reduce the risk of over-claiming;

- Calculating the SROI: This stage outlines how to summarize the financial information recorded in the previous steps to calculate the SROI ratio. The ratio is calculated as follows:SROI = Net Impact Value/Net present Value of Investment;

- Reporting, using, and embedding: The final step involves sharing findings with stakeholders and integrating the successful outcomes into organizational practices.

While various methods exist for assessing organizational impacts, such as Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and other ESG frameworks, these often focus only on specific dimensions of sustainability or provide qualitative insights without monetization (Baiano, 2021). LCA, for instance, is widely adopted in the wine sector for evaluating environmental impacts but lacks the ability to account for social or economic contributions systematically (Curran, 2014). In contrast, the SROI methodology explicitly quantifies social and environmental outcomes in monetary terms, enabling the calculation of a ratio that reflects the social value generated per Euro invested (Corvo et al., 2022; Cagarman et al., 2023). This aligns with the wine industry’s need to demonstrate value creation across different dimensions and to enhance transparency, stakeholder engagement, and strategic alignment with sustainability goals.

2.2. The Role of SROI for the Impact Assessment in the Agricultural and Wine Sector

Agriculture is undergoing a transformation due to growing environmental concerns, increasing pressure for social responsibility, and the need for long-term economic viability (Dönmez et al., 2024; Wollni et al., 2025). As a result, sustainability and impact assessment methods have been developed to measure the environmental, economic, and social impacts of agricultural activities (Zhang, 2024; Maciel Pinto et al., 2024; Bernetti et al., 2012).

These methodologies aim to move beyond traditional financial accounting and provide a more holistic evaluation of the true costs and benefits of farming practices (Baiano, 2021). The sustainability of production systems has also been evaluated based on their interactions with biodiversity (Rabeschini et al., 2025).

Historically, sustainability in agriculture has typically been evaluated through three interconnected dimensions (Wagner et al., 2023): (a) Environmental sustainability, which includes carbon footprint assessments, water usage efficiency, biodiversity preservation, and chemical input reduction; (b) Social sustainability, which includes the evaluation of fair labor practices, rural development, and community well-being; and c) Economic sustainability, which assesses cost-efficient resource management and market competitiveness.

One of the most widely used sustainability assessment methods is Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), which quantifies environmental impact throughout the entire production chain (Baiano, 2021). However, LCA is often limited to environmental factors and does not fully capture social and economic benefits (Marsh et al., 2025; Martínez-Ramón et al., 2025; Curran, 2014; Fauzi et al., 2019).

Therefore, alternative frameworks such as SROI are increasingly used to evaluate the broader value generated by agricultural projects (Tulla et al., 2018; Klemelä, 2016). In particular, the existing literature shows how SROI has been applied to Community-Supported Agriculture (CSA) initiatives (Medici et al., 2023) and to Social Farming, a practice that integrates agricultural activities with social services for marginalized groups (Basset, 2023).

A case study in Catalonia, Spain, examined 161 social farming projects using SROI analysis (Tulla et al., 2018). Key findings included that SROI ratios ranged from EUR 2 to EUR 3 per EUR 1 invested, demonstrating high social returns. The greatest impacts were observed in employment opportunities, mental health improvements, and community cohesion, confirming that stakeholder engagement played a crucial role in ensuring the effectiveness of SROI.

Recent studies have also suggested that combining non-exclusively environmental methodologies with environmental assessment tools can improve their applicability (Zamagni et al., 2013; Vázquez-Rowe et al., 2021), paving the way for the integration of SROI with other methodologies.

Despite its advantages, the existing literature also shows that applying SROI in agricultural sustainability faces several challenges (Pathak & Dattani, 2014). These include the complexity of measuring and monetizing environmental impacts (Feor et al., 2023); the variability in stakeholder expectations and priorities (Basset, 2023); and the lack of standardized methodologies, as many SROI studies use different indicators, making comparative analysis difficult (Baiano, 2021).

Moreover, the applications of SROI in agriculture examined in the existing literature have predominantly focused on outcomes related to food security, employment generation, and rural development. Such a focus, while important, often overlooks the complex intersections of economic, environmental, and cultural dimensions inherent in wine production, which extends beyond farming to include tourism, hospitality, and regional identity (Gilinsky et al., 2016). Furthermore, the proxies commonly used in agricultural SROI studies tend to generalize social value, making it difficult to capture intangible benefits such as consumer experience, cultural heritage preservation, and brand reputation, which are integral to the wine sector’s societal contributions.

These limitations suggest that, while SROI is a promising framework, its application in agriculture has not sufficiently addressed the unique characteristics and value creation processes specific to the wine industry. Consequently, there is a need for studies that critically examine and adapt the SROI methodology to account for the multidimensional nature of the wine sector, incorporating experiential, cultural, and environmental impacts alongside economic indicators. This study responds to that gap by exploring the potential and limitations of SROI within the wine industry, aiming to refine the methodology to better align with the sector’s complexity and to support wineries in quantifying and communicating their comprehensive contributions to sustainability and stakeholder well-being.

3. Materials and Methods

The wine industry is not only a driver of rural development but also a key player in the transition toward environmentally responsible production (Marshall et al., 2005). Wineries operate within highly regulated markets that increasingly emphasize Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and environmental sustainability (Bandinelli et al., 2020). By evaluating its triple-bottom-line impact, the wine industry can serve as a benchmark for other agricultural industries looking to integrate sustainability into their business models (Gilinsky et al., 2016; Mariani & Vastola, 2015).

In order to obtain a comprehensive overview of the current landscape of the Italian wine industry, a questionnaire (Supplementary Materials) comprising 16 sections was created according to the existing literature on the topic (Pizzol et al., 2021; Corbo et al., 2014), covering both descriptive business characteristics (e.g., company size, production volume, business model) and sustainability, impact assessment and social responsibility practices (e.g., stakeholder engagement, environmental impact reduction strategies, circular economy initiatives, and corporate communication channels). The survey also explored the role of innovation, the perception of territorial identity in wine production, and the effects of certification constraints on experimentation. The final sections addressed the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on corporate well-being and resilience strategies. Categorical questions were used to ensure clarity and consistency across a diverse sample, facilitating higher response rates from stakeholders. Moreover, categorical questions were chosen to mitigate the risks related to stakeholder self-reporting, which, although it enables direct insight into perceived outcomes, also introduces limitations such as social desirability bias, recall error, and over- or underestimation of impact. This limitation is inherent to most participatory SROI assessments and should be considered when interpreting results (Arvidson et al., 2013).

The data collected were analyzed using descriptive statistical methods, providing a quantitative summary of industry-wide trends and sustainability efforts. Responses were aggregated to identify patterns in social and environmental responsibility, assessing the degree of adoption of CSR strategies and sustainability certifications. Additionally, qualitative responses were examined to capture insights into perceived challenges and opportunities within the sector. Overall, the analysis of the scientific and grey literature, along with the analysis of the questionnaire results, contributed to answering the first Research Question. Informed consent for participation in this study was obtained verbally from all participants. Verbal consent was chosen because this study involved minimal risk to participants, and all data were collected anonymously.

Afterward, the findings from this preliminary research served as a contextual foundation for the subsequent SROI case study, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of the broader industry dynamics that shape the social impact of wine cellars. The SROI case study was conducted on the wine cellar called Duca di Salaparuta, a Sicilian wine group, which is a part of a larger group controlled by the Reina Family. The stakeholders of the wine cellar, divided into 5 categories, were engaged through interviews and four questionnaires (Supplementary Materials Sections B–E), resulting in a total of 50 responses collected.

According to the SROI methodology, specific outcomes were identified for each stakeholder’s category through the interviews and the questionnaires, describing what actually changes for them as a result of the firm’s activities. Afterward, for each stakeholder group, the respective impact amount was calculated by assigning value to outcomes through indicators and attributing monetary value via financial proxies, which are used to estimate the social value of non-traded goods. In order to assign a monetary value to the outcomes for different stakeholder categories, in particular, the financial proxies are intended as estimates which represent the economic worth of non-traded goods, that are calculated by identifying a real-world good, service, or cost that closely reflects the value of the outcome through sources that include government databases, academic studies, economic evaluations, willingness-to-pay surveys, or stakeholder consultations. In particular, each proxy was estimated based on publicly available and sector-specific market data and, where possible, validated through triangulation comparing values across at least two independent sources and testing for local relevance through stakeholder consultation, to reduce bias and ensure context-appropriate valuation. For instance, one proxy used was the monetary value of online courses (e.g., on corporate communication or problem-solving) to represent the value of social and cognitive skills development for employees. This proxy was calculated using average costs of online courses from major platforms (Coursera, Udemy, edX, etc.) and resulted in a proxy value of EUR 200 per stakeholder. This value was then compared against the relevant investment costs to calculate the SROI ratio.

The raw impact value is then adjusted for impact factors: deadweight, attribution, displacement, and drop-off. This yields a net impact value for each outcome, which—after the application of a discount rate of 3.5% as recommended by the methodology—provides the total social value generated by the intervention. Finally, the SROI index is calculated by dividing the net impact value by the net present value of the firm’s investments.

4. Results

4.1. Impact Assessment and Sustainability Practices in the Italian Wine Industry

The questionnaire aimed at providing an overview of the sustainability trends, impact assessment practices, and Corporate Social Responsibility initiatives undertaken by the Italian wine industry was administered to a sample of 18 Italian wine cellars from different Italian Regions. The objective was to analyze industry characteristics, sustainability initiatives, and correlation trends.

The findings indicate that most wineries (72.22%) are small firms with more than 10 employees and annual revenues below EUR 10 M, while 22.22% are micro-enterprises and 5.56% are large firms with revenues exceeding EUR 50 M. A strong correlation was found between firm size and production volume, as larger wineries tend to produce more bottles annually. Additionally, older wineries tend to be larger, suggesting gradual expansion over time. The degree of vertical integration also correlates with firm size, with smaller wineries handling fewer production stages, whilst larger firms tend to integrate multiple stages internally.

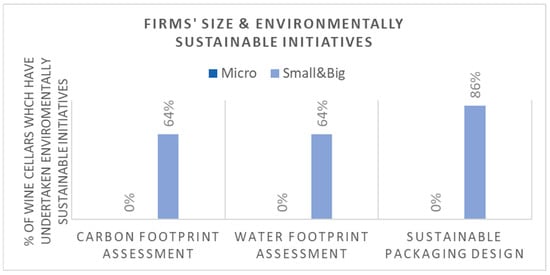

Sustainability practices vary by size (Figure 2). Micro-enterprises do not engage in carbon or water footprint assessments, whereas 64% of small and large wineries do. Similarly, 86% of larger wineries use sustainable packaging, reflecting a higher adoption of environmentally responsible practices. A comparable trend is observed in social initiatives, where 79% of small and large wineries engage in ethical and educational community programs, while micro firms do not.

Figure 2.

Firms’ size and environmentally sustainable initiatives.

The analysis also reveals a negative correlation between service diversification and both production volume and vertical integration. Wineries focused on bottle sales and traditional winemaking are less likely to offer additional services such as wine tastings, guided tours, or hospitality offerings. Conversely, wineries with lower production volumes tend to diversify their business by offering multiple services.

Finally, regarding the adoption of impact assessment practices, the positive correlation between vertical integration and sustainability efforts suggests that wineries controlling more stages of production actively manage their environmental impact. Less attention is currently given to social and governance aspects of the sustainability spectrum. Moreover, most wineries have not adopted any formal impact evaluation framework (SROI or any other framework), while only 11% have implemented LCA.

Table 1 summarizes the main findings of the analysis aimed at identifying the current key trends within the wine industry regarding sustainability practices and CSR initiatives.

Table 1.

Key trends about sustainability practices and impact assessment initiatives in the Italian wine industry.

4.2. Potential and Limitations of SROI in the Wine Industry: Results from a Wine Cellar Case Study

Duca di Salaparuta is the largest private wine group in Sicily, classified as an SME, with three estates and three wine brands. The company operates across two markets, selling high-quality wines to restaurants and lower-quality wines to large retailers. It fully integrates the wine production process, with its Palermo plants handling still and sparkling wines, while its Marsala facility produces fortified wines.

Beyond wine production, the company offers wine tastings and seasonal events. Its main sustainability efforts include water and energy consumption optimization, with initiatives such as a recycled rinse water system and an energy consumption assessment to set future improvement goals. A dedicated interview confirmed the correlations observed in the questionnaire results, showing that older and larger wineries tend to be more vertically integrated and engaged in sustainability initiatives, as demonstrated by Duca di Salaparuta’s water footprint assessment efforts.

The Duca di Salaparuta wine cellar was the subject of an SROI analysis. Five relevant stakeholder categories were identified:

- Bottle clients;

- Wine-testing service clients;

- Employees;

- Suppliers;

- Shareholders.

These stakeholders were engaged through an interview with the Quality Manager and questionnaires (Supplementary Materials Sections B–E) with the aim of identifying the outcomes that reflect how the firm impacts them and to what extent. The number of responses received was 20 for questionnaires B and C and 5 for questionnaires D and E, for a total of 50 responses. The inputs included all operating costs reported in the firm’s income statement, amounting to approximately EUR 46.32 M (Net Present Value of Investments).

Table 2 reports the outcomes identified for each stakeholder category through the interviews and questionnaires, describing what actually changes for them as a result of the firm’s activities. Moreover, for each stakeholder, the corresponding impact amount is reported in Table 2, calculated by assigning value to the outcomes via indicators and applying monetary values through financial proxies.

Table 2.

Impact Map of the SROI Analysis.

Next, deadweight, displacement, attribution, and drop-off were taken into account to compute the actual impact delivered. In order to calculate the present value, the resulting net impact value was discounted using a rate of 3.5%. This resulted in a total of approximately EUR 66.5 M (Table 3), representing the Total Social Value delivered by the Duca di Salaparuta wine cellar. The estimated SROI ratio is 1.44 (Table 3), indicating that for each Euro invested by the firm, EUR 1.44 of social value was generated.

Table 3.

Result of the SROI Analysis.

Moreover, a sensitivity analysis (Table 4) was carried out in order to enhance the reliability of the SROI analysis. In particular, when calculating the impact on clients who purchased bottles, the number of these clients was a fundamental data point. Since the figure provided by the Quality Manager also included large retailers, the number of final clients was estimated as a percentage of the total number of bottles produced, which is 8.5 M.

Table 4.

Sensitivity analysis.

Thus, the sensitivity analysis was based on the variation in the assumption regarding the number of final clients who purchase the wine bottles. The company continues to generate positive social value up to the fourth scenario, which assumes that only 50% of the bottles produced during the year reach final consumers. Eventually, the scenario chosen to estimate the SROI ratio is the third, which applies a cautious percentage of wine bottles, acknowledging that some may be stocked by retailers and that a single client may purchase more than one bottle. This scenario assumes 5.1 M final clients and, as a result, yields an SROI ratio of 1.44.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to identify the main sustainability trends, impact assessment practices, and CSR initiatives, and examined the use of SROI, highlighting its potential to capture the social and environmental value created by wineries alongside their economic contributions. The findings indicate that applying SROI in the wine sector can yield meaningful insights into sustainability practices and stakeholder impacts, aligning with broader calls for holistic sustainability assessment in agri-food industries (Baiano, 2021; Gilinsky et al., 2016).

Similar to previous studies that have identified the utility of SROI in agricultural contexts (Tulla et al., 2018; Basset, 2023), the findings provide key insights into the applicability, advantages, and limitations of SROI in the wine industry, with potential applications to other sectors as well.

In particular, the findings of this study are broadly consistent with prior applications of SROI in agri-food contexts. Tulla et al. (2018) demonstrated that SROI can effectively capture multidimensional value, including environmental and cultural benefits, through stakeholder engagement and outcome monetization, similar to our identification of non-economic impacts within the wine industry. However, unlike Tulla’s urban agriculture case, where inclusion and social cohesion were dominant outcomes, our study found a higher relative emphasis on cultural preservation and ecosystem value. Basset (2023) highlighted persistent challenges in standardizing outcomes and validating proxies, issues our study also encountered when assigning consistent value to intangible benefits such as heritage and brand identity. Nevertheless, both studies confirm that, despite methodological limitations, SROI provides a valuable framework for uncovering and quantifying benefits often excluded from conventional economic metrics.

The main theoretical contributions of this study are that, while the application of SROI is still underexplored in the current literature, its implementation in the wine sector presents unique characteristics and opportunities compared to its use in other agricultural and service industries. The literature review highlighted that the most recurrent impact assessment methodologies in the Italian wine industry remain Life Cycle Assessment and Water Footprint (WF). However, as presented in Table 5, unlike conventional agriculture—where impact assessment focuses primarily on food production, land use, and environmental sustainability—the wine industry extends beyond farming to tourism, culture, and hospitality. This multidimensional nature makes SROI particularly relevant, as it enables wineries to capture the broader social and economic value they generate, from consumer experiences to rural economic development.

Table 5.

What differentiates the application of SROI in the wine sector from the application of SROI in other sectors?

Moreover, one of the main challenges of applying SROI in the wine industry is the monetization of experiential and cultural value. Unlike service industries, where social impact often follows more standardized financial metrics, wineries must quantify intangible benefits such as wine tourism, brand reputation, and consumer engagement. This makes the development of financial proxies particularly critical in SROI applications for wineries. Another fundamental characteristic of SROI is its strong stakeholder engagement component, which ensures that the perspectives of key actors—such as employees, customers, suppliers, and business owners—are systematically integrated into the impact assessment process. The participatory nature of this methodology, as evidenced by the interviews and questionnaires conducted in this study, facilitates a holistic evaluation of stakeholder experiences, making it possible to identify both tangible and intangible benefits derived from the winery’s operations. In doing so, SROI not only quantifies impact but also provides meaningful insights that can be leveraged to improve organizational strategies and enhance the company’s contribution to its broader socio-economic environment.

Another key distinction of SROI in the context of wine production, which emerged from this study, is its ability to assess the social impact of sustainable winemaking. As wineries adopt environmentally responsible practices, such as organic viticulture and carbon footprint reduction, SROI provides a framework to monetize these efforts, reinforcing the alignment between sustainability, business strategy, and stakeholder expectations. Unlike traditional sustainability assessments like LCA, which focus primarily on environmental indicators, SROI integrates economic, environmental, and social dimensions, offering a more holistic impact evaluation.

Regarding the main practical recommendations of this study, it explains why wineries should assess the impact of their sustainability efforts not only in environmental terms (e.g., organic viticulture, biodiversity conservation, circular economy models) but also in their economic and cultural contributions to regional development.

Moreover, this study confirms that SROI is a functional and viable methodology for assessing a winery’s social impact, offering a structured framework for quantifying social and environmental value in financial terms. Unlike traditional financial assessments, which primarily focus on economic indicators, SROI facilitates a more comprehensive evaluation by incorporating a triple-bottom-line perspective. The case study illustrates how SROI captures a broad spectrum of impacts beyond direct financial transactions, enabling the assessment of economic benefits for employees and suppliers, improvements in social well-being for consumers and communities, and environmental responsibility through sustainability initiatives.

One of the key strengths of SROI lies in its ability to provide a quantitative metric for social value, allowing organizations to express their social impact in monetary terms. This is particularly relevant for wineries, where the interplay between business performance and social contributions is increasingly scrutinized. The SROI ratio estimated in this study, which indicates that for every Euro invested, EUR 1.44 of social value is generated, demonstrates the potential of the methodology to offer concrete and measurable insights into the overall value created by a winery. The capacity of SROI to translate qualitative social benefits into financial metrics further enhances its utility for decision-making, stakeholder communication, and strategic planning.

Nonetheless, while a 1.44 SROI ratio indicates a positive return, it is relatively modest compared to other SROI ratios reported in social farming projects, which often exceed 2.0 due to strong community or employment-related outcomes (Tulla et al., 2018; Basset, 2023). This difference may be attributed to the more diffuse and intangible nature of cultural and environmental impacts in the wine sector. Additionally, the analysis revealed that larger wineries tended to report higher ratios, possibly due to greater capacity for structured sustainability programs, stakeholder engagement, and reporting practices, whereas smaller wineries may lack the resources to fully document or leverage their social contributions.

Moreover, it is important to note that direct comparisons across SROI ratios of different projects or organizations are discouraged (Banke-Thomas et al., 2015), due to the methodological subjectivity involved in selecting outcomes and financial proxies, as well as contextual variability such as stakeholder composition, local socio-economic conditions, and the scope of impact measured. As a result, SROI ratios are most meaningful when interpreted within the specific context of the project, rather than as absolute benchmarks across cases (Cooney & Lynch-Cerullo, 2014).

Based on the main findings of this study, we propose in Table 6 a set of practical steps to support the adoption of SROI in the wine industry, with tailored recommendations for both wineries and policymakers to enhance methodological rigor, stakeholder engagement, and strategic integration.

Table 6.

Recommendations for enhancing SROI adoption in the wine industry.

The application of SROI in this case study also highlighted its potential as a tool for organizational learning and development. The analysis process enabled Duca di Salaparuta to gain a deeper understanding of how its activities contribute to sustainability and stakeholder well-being, reinforcing the importance of integrating impact assessment into corporate decision-making. The findings suggest that, by adopting SROI, wineries can refine their business strategies, strengthen their communication about social responsibility, and enhance their positioning in an increasingly competitive and sustainability-driven market. Thus, the results of this study underscore the practical relevance of SROI in helping wineries systematically evaluate their social contributions, supporting a shift toward more responsible and transparent business practices in the wine industry.

Unlike traditional agricultural enterprises, wine cellars engage in activities that extend beyond farming, such as wine tourism, tasting experiences, and cultural events, all of which contribute to community engagement and economic development. The application of SROI in this context enables the quantification of these intangible benefits, offering a more comprehensive understanding of a winery’s impact.

By bridging the gap between traditional agricultural assessments and social impact evaluation, SROI presents a valuable tool for wineries to quantify and communicate their contributions to regional development, employment, and sustainability. As consumer expectations shift toward greater transparency and social responsibility, SROI enhances a winery’s ability to demonstrate its multifaceted value, reinforcing its role as a driver of sustainable economic and social progress.

6. Conclusions

The Social Return on Investment (SROI) methodology offers a comprehensive alternative to conventional investment evaluations by capturing social and environmental value alongside financial performance. It provides a structured framework to quantify diverse outcomes from a stakeholder perspective, making it especially relevant in an era when businesses are increasingly expected to align with sustainable and equitable goals.

This study applied SROI to the wine sector through a case study of Duca di Salaparuta, supported by a broader analysis of Italian wineries. The results show that every EUR 1 invested yields approximately EUR 1.44 in social value, demonstrating SROI’s potential to measure and communicate societal contributions effectively. It also enhances corporate transparency, stakeholder trust, and informed decision-making.

Moreover, the research underscores how the wine industry presents unique SROI challenges and opportunities. Unlike conventional agriculture, wineries also deliver cultural, experiential, and hospitality-related value, which are harder to monetize. Thus, applying SROI in this context requires the development of suitable proxies for intangible benefits like brand reputation, consumer engagement, and heritage preservation. Additionally, as wineries adopt environmentally responsible practices, such as organic viticulture, biodiversity conservation, and carbon footprint reduction, SROI enables them to monetize these sustainability efforts, reinforcing alignment with corporate strategy and stakeholder expectations.

Despite its benefits, SROI has limitations, particularly the subjectivity of proxies and challenges in cross-company benchmarking. Specifically, the use of financial proxies inherently involves a degree of subjectivity, as assigning monetary values to intangible outcomes (e.g., cultural heritage, brand identity) depends on assumptions and available data. While this can be mitigated by using validated sources and triangulating proxy values where possible, variation in interpretation remains a methodological constraint.

Other limitations of this study concern the relatively small sample size, which limits the generalizability of the findings across the broader Italian wine industry. Although participants represented diverse winery types and sizes, the sample may not capture the full heterogeneity of practices. Furthermore, both interviews and questionnaires relied on self-reported data, which introduces potential bias due to recall error, social desirability, or selective reporting. While this was partially controlled through clear question design and cross-checking between data sources, these biases are common in participatory methodologies and should be considered when interpreting the results.

Notwithstanding its limitations, the SROI methodology enables valuable internal comparisons over time and encourages organizations to refine sustainability strategies. The findings also suggest that SROI can drive innovation and help wineries enhance their market positioning by better communicating their impact to stakeholders.

Beyond these methodological challenges, this study also highlights the broader implications of SROI adoption in the wine sector. The results suggest that implementing SROI assessments can serve as a catalyst for innovation, fostering greater awareness among businesses regarding their social and environmental footprint. By systematically measuring their impact, wineries can refine their strategies, identify areas for improvement, and enhance their sustainability credentials, which is particularly critical in an industry increasingly shaped by ethical consumption trends and investor expectations. Furthermore, from a managerial perspective, integrating SROI into corporate practices can facilitate more transparent communication with stakeholders, improve Corporate Social Responsibility initiatives, and strengthen market positioning in an era where sustainability is a competitive advantage.

Future research should focus on standardizing SROI metrics within the wine industry, establishing sector-specific benchmarks that would enhance comparability across different wineries and regions. Additionally, exploring hybrid methodologies, such as integrating SROI with LCA and other environmental impact assessment tools, could provide a more comprehensive sustainability evaluation framework. Given the growing regulatory emphasis on ESG reporting, further studies could also investigate how SROI findings can be effectively incorporated into corporate sustainability disclosures and decision-making processes at an institutional level. Moreover, the development of industry-specific proxies, particularly for cultural and experiential benefits, should be taken into consideration as a future research avenue, ensuring a more accurate valuation of the wine sector’s social contributions.

In conclusion, while methodological challenges remain, this study confirms that SROI is a robust tool for evaluating and communicating the social impact of wineries. It supports the transition to impact-driven business models in agriculture, particularly in sectors like wine production that blend tradition, innovation, and sustainability. Wineries adopting SROI can strengthen their accountability, foster innovation, and contribute to more inclusive rural development, setting a benchmark for other agri-food and consumer-focused industries striving to balance profitability with social responsibility.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/admsci15090346/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.L.; methodology, A.M. and P.L.; validation, P.L.; data curation, P.L.; writing—original draft, A.M. and P.L.; writing—review and editing, A.M. and P.L.; supervision, P.L.; visualization, A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

According to the policies of University, studies involving human participants that pose only minimal risk and involve fully anonymous data collection do not require prior approval from the ethics committee. As our study meets these criteria (minimal risk and complete anonymity of the data) ethical approval was not required.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation in the study was obtained verbally from all the participants. The verbal consent was chosen because the study involved minimal risk to participants and all data were collected anonymously.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contribution of Elena Manno, Nader Tayser, and Giovanni Lombardo in the data collection phase.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CSA | Community-Supported Agriculture |

| CSR | Corporate Social Responsibility |

| ESG | Environment, Social, and Governance |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| RQ | Research Question |

| SROI | Social Return on Investment |

| WF | Water Footprint |

References

- Arvidson, M., Lyon, F., McKay, S., & Moro, D. (2013). Valuing the social? The nature and controversies of measuring social return on investment (SROI). Voluntary Sector Review, 4(1), 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashenfelter, O., & Storchmann, K. (2016). Climate change and wine: A review of the economic implications. Journal of Wine Economics, 11(1), 105–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiano, A. (2021). An overview on sustainability in the wine production chain. Beverages, 7(1), 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandinelli, R., Acuti, D., Fani, V., Bindi, B., & Aiello, G. (2020). Environmental practices in the wine industry: An overview of the Italian market. British Food Journal, 122(5), 1625–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banke-Thomas, A. O., Madaj, B., Charles, A., & van den Broek, N. (2015). Social Return on Investment (SROI) methodology to account for value for money of public health interventions: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 15, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basset, F. (2023). The evaluation of social farming through social return on investment: A review. Sustainability, 15(4), 3854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernetti, I., Menghini, S., Marinelli, N., Sacchelli, S., & Sottini, V. A. (2012). Assessment of climate change impact on viticulture: Economic evaluations and adaptation strategies analysis for the Tuscan wine sector. Wine Economics and Policy, 1(1), 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bux, H., Zhang, Z., & Ali, A. (2024). Corporate social responsibility adoption for achieving economic, environmental, and social sustainability performance. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 10, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagarman, K., Fajga, K., & Kratzer, J. (2023). Capturing the sustainable impact of early-stage business models: Introducing esSROI. Highlights of Sustainability, 2, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conto, F., Vrontis, D., Fiore, M., & Thrassou, A. (2014). Strengthening regional identities and culture through wine industry cross border collaboration. British Food Journal, 116(11), 1788–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooney, K., & Lynch-Cerullo, K. (2014). Measuring the social returns of nonprofits and social enterprises: The promise and perils of the SROI. In Nonprofit policy forum (Vol. 5, pp. 367–393). De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Corbo, C., Lamastra, L., & Capri, E. (2014). From environmental to sustainability programs: A review of sustainability initiatives in the Italian wine sector. Sustainability, 6(4), 2133–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corvo, L., Pastore, L., Mastrodascio, M., & Cepiku, D. (2022). The social return on investment model: A systematic literature review. Meditari Accountancy Research, 30(7), 49–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, M. A. (2014). Strengths and limitations of life cycle assessment. In Background and future prospects in life cycle assessment (pp. 189–206). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Damtoft, N. F., Lueg, R., van Liempd, D., & Nielsen, J. G. (2023). A critical perspective on the measurement of social value through SROI. In Social Value, Climate Change and Environmental Stewardship: Insights from Theory and Practice (pp. 13–32). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Deep, G. (2023). The influence of corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. Magna Scientia Advanced Research and Reviews, 9(2), 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra-Silva, S., Schaltegger, S., & Beske-Janssen, P. (2022). Understanding positive contributions to sustainability. A systematic review. Journal of Environmental Management, 320, 115802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dönmez, D., Isak, M. A., İzgü, T., & Şimşek, Ö. (2024). Green horizons: Navigating the future of agriculture through sustainable practices. Sustainability, 16(8), 3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, P., E Silva, S. C., Mangei, I., & Dias, J. C. (2024). Exploring ethical consumer behavior: A comprehensive study using the ethically minded consumer behavior-scale (EMCB) among adult consumers. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 21, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumre, A., Kolady, D., Grebitus, C., & Ishaq, M. (2025). Drivers of likelihood to consume carbon-friendly beef and plant-based meat in the United States. Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 50(1), 39–61. [Google Scholar]

- Fauzi, R. T., Lavoie, P., Sorelli, L., Heidari, M. D., & Amor, B. (2019). Exploring the current challenges and opportunities of life cycle sustainability assessment. Sustainability, 11(3), 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feor, L., Clarke, A., & Dougherty, I. (2023). Social impact measurement: A systematic literature review and future research directions. World, 4(4), 816–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichter, K., Lüdeke-Freund, F., Schaltegger, S., & Schillebeeckx, S. J. D. (2023). Sustainability impact assessment of new ventures: An emerging field of research. Journal of Cleaner Production, 384, 135452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flockhart, A. (2005). Raising the profile of social enterprises: The use of social return on investment (SROI) and investment ready tools (IRT) to bridge the financial credibility gap. Social Enterprise Journal, 1(1), 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilinsky, A., Jr., Newton, S. K., & Vega, R. F. (2016). Sustainability in the global wine industry: Concepts and cases. Agriculture and agricultural Science Procedia, 8, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gionfriddo, G., & Piccaluga, A. (2024). Startups’ contribution to SDGs: A tailored framework for assessing social impact. Journal of Management & Organization, 30, 545–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosselin, V., Boccanfuso, D., & Laberge, S. (2020). Social return on investment (SROI) method to evaluate physical activity and sport interventions: A systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerra, M., Ferreira, F., Oliveira, A. A., Pinto, T., & Teixeira, C. A. (2024). Drivers of environmental sustainability in the wine industry: A life cycle assessment approach. Sustainability, 16(13), 5613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haski-Leventhal, D., & Mehra, A. (2016). Impact measurement in social enterprises: Australia and India. Social Enterprise Journal, 12(1), 78–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y., & Bui, T. H. G. (2022). Consumers’ perspectives and behaviors towards corporate social responsibility—A cross-cultural study. Sustainability, 14(2), 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, R. J., Wessells, C. R., Donath, H., & Asche, F. (2001). Measuring consumer preferences for ecolabeled seafood: An international comparison. Journal of Agricultural and resource Economics, 26, 20–39. [Google Scholar]

- Jonas, J. M., Boha, J., Sörhammar, D., & Moeslein, K. M. (2018). Stakeholder engagement in intra-and inter-organizational innovation: Exploring antecedents of engagement in service ecosystems. Journal of Service Management, 29(3), 399–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, C. (2002). Sustainability Impact Assessment (SIA): A methodology for assessing the impact of development projects and programmes. Transformation, 19(2), 118–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemelä, J. (2016). Licence to operate: Social Return on Investment as a multidimensional discursive means of legitimating organisational action. Social Enterprise Journal, 12(3), 387–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kour, M. (2024). Understanding the drivers of green consumption: A study on consumer behavior, environmental ethics, and sustainable choices for achieving SDG 12. SN Business & Economics, 4(9), 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingane, A., & Olsen, S. (2004). Guidelines for social return on investment. California Management Review, 46(3), 116–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovrinčević, M., Škokić, V., & Bilić, I. (2025). Assessing the impact of social media on family business performance: The case of small wineries in split-dalmatia county. Administrative Sciences, 15(6), 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel Pinto, D., Bin, A., Ferré, M., Turner, J. A., Stachetti Rodrigues, G., Costa, M. M., Pereiro, M. S., Mechelk, J., de Romemont, A., & Heanue, K. (2024). Data-driven R&D&I management for societal impacts: Introduction and application of AgroRadarEval. Journal of Technology Management & Innovation, 19(4), 89–112. [Google Scholar]

- Maier, F., Schober, C., Simsa, R., & Millner, R. (2015). SROI as a method for evaluation research: Understanding merits and limitations. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 26, 1805–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, M., & Corbey, M. (2016). Social Return on Investment (SROI): A review of the technique. Maandblad Voor Accountancy en Bedrijfseconomie, 90, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, A., & Vastola, A. (2015). Sustainable winegrowing: Current perspectives. International Journal of Wine Research, 7, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marozzo, V., Costa, A., & Abbate, T. (2024). The relationship between the perceived product sustainability of organic food and willingness to buy: A parallel mediation effect of product traceability and consumers’ environmental concerns. Italian Journal of Marketing, 2024(4), 375–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, E., Hattam, L., & Allen, S. (2025). A method to create weighted-average life cycle impact assessment results for construction products, and enable filtering throughout the design process. Journal of Cleaner Production, 491, 144467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, R. S., Cordano, M., & Silverman, M. (2005). Exploring individual and institutional drivers of proactive environmentalism in the US wine industry. Business Strategy and the Environment, 14(2), 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Ramón, V., Bromwich, T., Modernel, P., Poore, J., & Bull, J. W. (2025). Alternative life cycle impact assessment methods for biodiversity footprinting could motivate different strategic priorities: A case study for a dutch dairy multinational. Business Strategy and the Environment, 34(2), 2128–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsali, C., Skordoulis, M., Papagrigoriou, A., & Kalantonis, P. (2025). ESG scores as indicators of green business strategies and their impact on financial performance in tourism services: Evidence from worldwide listed firms. Administrative Sciences, 15(6), 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medici, M., Canavari, M., & Castellini, A. (2023). An analytical framework to measure the social return of community-supported agriculture. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 47(9), 1319–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, P. A., & Loureiro, M. L. (2016). Economic valuation of climate-change-induced vinery landscape impacts on tourism flows in Tuscany. Agricultural Economics, 47(4), 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, P., & Dattani, P. (2014). Social return on investment: Three technical challenges. Social Enterprise Journal, 10(2), 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan-Le, N. T., Brennan, L., & Parker, L. (2024). An integrated model of the sustainable consumer. Sustainability, 16(7), 3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzol, L., Luzzani, G., Criscione, P., Barro, L., Bagnoli, C., & Capri, E. (2021). The role of corporate social responsibility in the wine industry: The case study of Veneto and Friuli Venezia Giulia. Sustainability, 13(23), 13230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomarici, E., Corsi, A., Mazzarino, S., & Sardone, R. (2021). The Italian wine sector: Evolution, structure, competitiveness and future challenges of an enduring leader. Italian Economic Journal, 7(2), 259–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabeschini, G., Persson, U. M., West, C., & Kastner, T. (2025). Choosing fit-for-purpose biodiversity impact indicators for agriculture in the Brazilian Cerrado ecoregion. Nature Communications, 16(1), 1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roma Business School. (2024). Italy in the global wine market: Evolution and prospects. Roma Business School. [Google Scholar]

- Rotheroe, N., & Richards, A. (2007). Social return on investment and social enterprise: Transparent accountability for sustainable development. Social Enterprise Journal, 3(1), 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trautwein, C. (2021). Sustainability impact assessments of start-ups—Key insights on relevant assessment challenges and approaches based on an inclusive, systematic literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 281, 125330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulla, A. F., Vera, A., Valldeperas, N., & Guirado, C. (2018). Social return and economic viability of social farming in Catalonia: A case-study analysis. European Countryside, 10(3), 398–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.K. Social Value. (2012). A guide to social return on investment. Institute for Social Value, London. [Google Scholar]

- Valdelomar-Muñoz, S., & Murgado-Armenteros, E. M. (2024). Environmental concerns of Agri-food product consumers: Key factors. Agriculture, 14(7), 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanclay, F. (2003). International principles for social impact assessment. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal, 21, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanclay, F. (2006). Principles for social impact assessment: A critical comparison between the international and US documents. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 26(1), 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Rowe, I., Córdova-Arias, C., Brioso, X., & Santa-Cruz, S. (2021). A method to include life cycle assessment results in choosing by advantage (Cba) multicriteria decision analysis. A case study for seismic retrofit in peruvian primary schools. Sustainability, 13(15), 8139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M., Stanbury, P., Dietrich, T., Döring, J., Ewert, J., Foerster, C., Freund, M., Friedel, M., Kammann, C., Koch, M., Owtram, T., Schultz, H. R., Voss-Fels, K., & Hanf, J. (2023). Developing a sustainability vision for the global wine industry. Sustainability, 15(13), 10487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wekesa, J. (2024). Impact of CSR (corporate social responsibility) on consumer behavior. International Journal of Marketing Strategies, 6(2), 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K., Habib, R., & Hardisty, D. J. (2019). How to shift consumer behaviors to be more sustainable: A literature review and guiding framework. Journal of Marketing, 83(3), 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollni, M., Bohn, S., Ocampo-Ariza, C., Paz, B., Santalucia, S., Squarcina, M., Umarishavu, F., & Wätzold, M. Y. L. (2025). Sustainability standards in agri-food value chains: Impacts and trade-offs for smallholder farmers. Agricultural Economics, 56, e70005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, B. T., & Marra, M. (2017). Introduction: Social return on investment (SROI). Evaluation and Program Planning, 64, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamagni, A., Pesonen, H. L., & Swarr, T. (2013). From LCA to life cycle sustainability assessment: Concept, practice and future directions. The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 18, 1637–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q. F. (2024). From sustainable agriculture to sustainable agrifood systems: A comparative review of alternative models. Sustainability, 16(22), 9675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).