Board Gender Diversity and Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Disclosure in Developed Countries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis Development

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample and Data Sources

3.2. Measurement of Variables

3.3. Methods

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Correlation Analysis

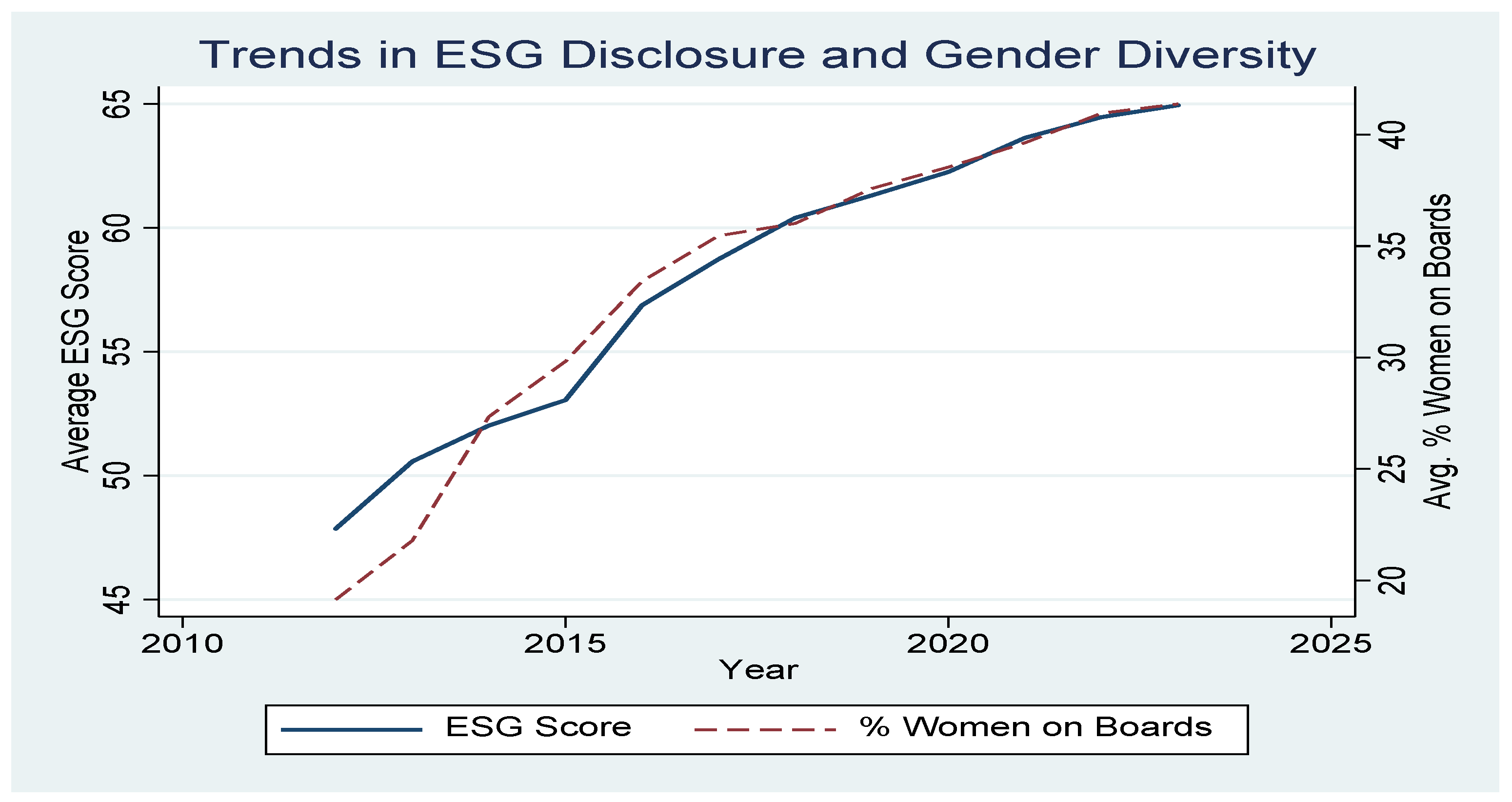

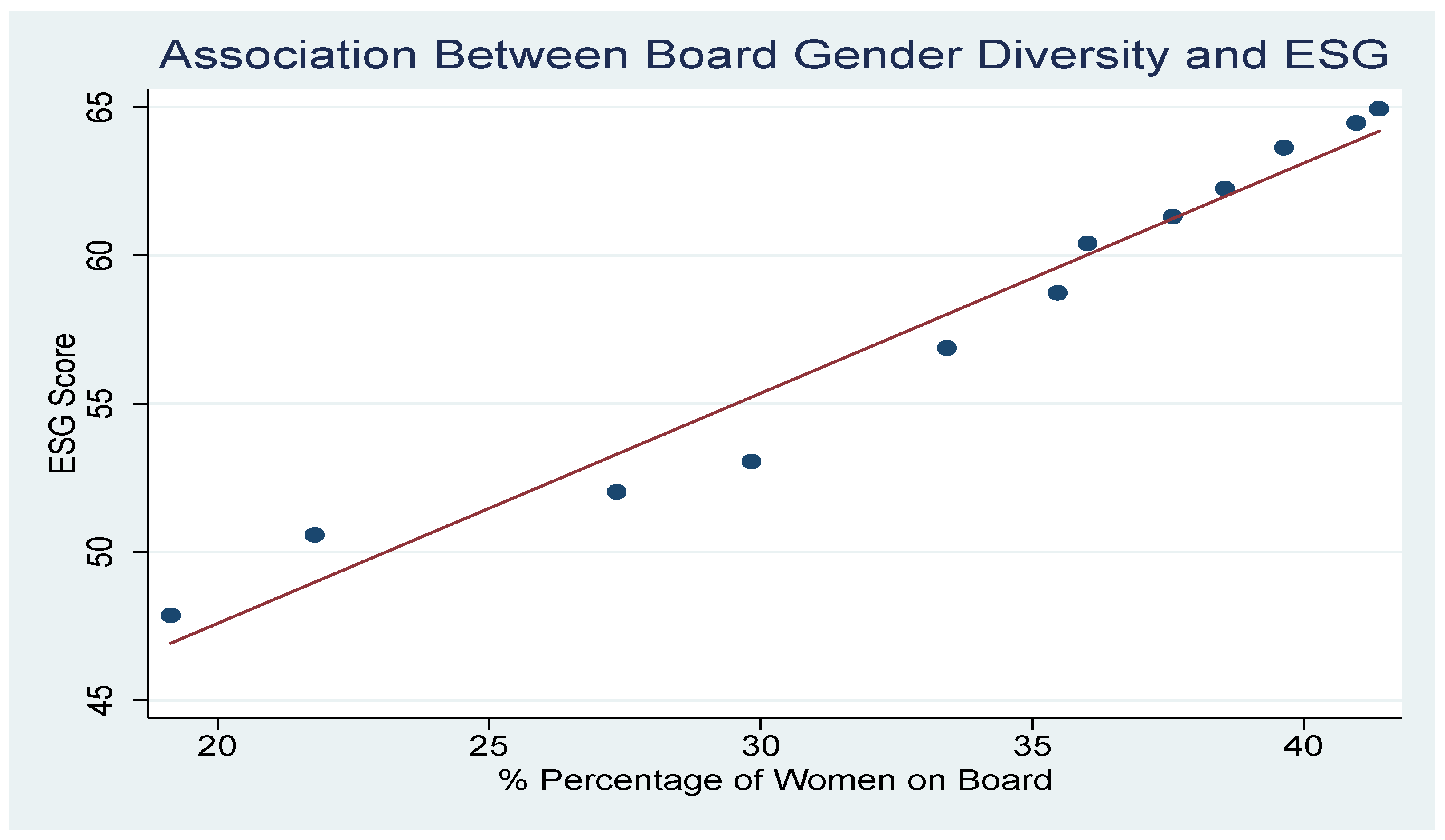

Graphical Analysis

4.3. Regression on the Impact of Board Gender Diversity on ESG Score

4.4. Robustness Checks

4.4.1. Alternative Board Gender Diversity Measures

4.4.2. Cross-Industry Comparison of Gender Diversity and ESG Disclosure

4.4.3. Alternative Sample (UK FSTE 100)

4.4.4. Inverse Probability Weighting (IPW) Regression

5. Conclusions

Study Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdelkader, M. G., Gao, Y., & Elamer, A. A. (2024). Board gender diversity and ESG performance: The mediating role of temporal orientation in South Africa context. Journal of Cleaner Production, 440, 140728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alareeni, B. A., & Hamdan, A. (2020). ESG impact on performance of US S&P 500-listed firms. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 20(7), 1409–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazzani, A., Hassanein, A., & Aljanadi, Y. (2017). Impact of gender diversity on social and environmental performance: Evidence from Malaysia. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 17(2), 266–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albitar, K., Abdoush, T., & Hussainey, K. (2023). Do corporate governance mechanisms and ESG disclosure drive CSR narrative tones? International Journal of Finance & Economics, 28(4), 3876–3890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A., Rehman, R. U., Ali, R., & Ntim, C. G. (2022). Does gender diversity on the board reduce agency costs? Evidence from Pakistan. Gender in Management an International Journal, 37(2), 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorelli, M., & García-Sánchez, I. (2021). Trends in the dynamic evolution of board gender diversity and corporate social responsibility. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 28(2), 537–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arayssi, M., Dah, M., & Jizi, M. (2016). Women on boards, sustainability reporting, and firm performance. Sustainability Accounting Management and Policy Journal, 7(3), 376–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arhinful, R., Mensah, L., & Owusu-Sarfo, J. S. (2024). Board governance and ESG performance in Tokyo stock exchange-listed automobile companies: An empirical analysis. Asia Pacific Management Review, 29(4), 397–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atif, M., Alam, M. S., & Hossain, M. (2020). Firm sustainable investment: Are female directors greener? Business Strategy and the Environment, 29(8), 3449–3469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldini, M., Maso, L. D., Liberatore, G., Mazzi, F., & Terzani, S. (2018). Role of country-and firm-level determinants in environmental, social, and governance disclosure. Journal of Business Ethics, 150(1), 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltagi, B. H. (2005). Econometric analysis of panel data (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Bamahros, H. M., Alquhaif, A., Qasem, A., Wan-Hussin, W. N., Thomran, M., Al-Duais, S. D., Shukeri, S. N., & Khojally, H. M. A. (2022). Corporate governance mechanisms and ESG reporting: Evidence from the Saudi Stock Market. Sustainability, 14(10), 6202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bart, C., & McQueen, G. (2013). Why women make better directors. International Journal of Business Governance and Ethics, 8(1), 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, C. F., Schaffer, M. E., & Stillman, S. (2003). Instrumental Variables and GMM: Estimation and testing. The Stata Journal Promoting Communications on Statistics and Stata, 3(1), 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beji, R., Yousfi, O., Loukil, N., & Omri, A. (2021). Board diversity and corporate social responsibility: Empirical evidence from France. Journal of Business Ethics, 173, 133–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, S. J., & Biswas, P. (2019). Board gender composition, dividend policy and COD: The implications of CEO duality. Accounting Research Journal, 32(3), 454–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, J. K., Pfeffer, J., & Salancik, G. R. (1978). The external control of organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 23(2), 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S., & Marwaha, D. (2022). The influence of board factors and gender diversity on the ESG disclosure Score: A study on Indian companies. Global Business Review, 23(6), 1544–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birindelli, G., Dell’Atti, S., Iannuzzi, A. P., & Savioli, M. (2018). Composition and activity of the Board of Directors: Impact on ESG performance in the banking system. Sustainability, 10(12), 4699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bit, N. E. a. A., & Pasaribu, P. (2024). The Relationship between macroeconomic variables and ESG index: Evidence from six emerging markets. Quantitative Economics and Management Studies, 5(6), 1218–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahma, S., Nwafor, C., & Boateng, A. (2021). Board gender diversity and firm performance: The UK evidence. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 26(4), 5704–5719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. C., & Roberts, R. W. (2010). Toward a more coherent understanding of the organization–society relationship: A theoretical consideration for social and environmental accounting research. Journal of Business Ethics, 97(4), 651–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, A., & Glass, C. (2018). Women on corporate boards: Do they advance corporate social responsibility? Human Relations, 71(7), 897–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cragg, J. G., & Donald, S. G. (1993). Testing identifiability and specification in instrumental variable models. Econometric Theory, 9(2), 222–240. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3532477 (accessed on 5 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Cucari, N., De Falco, S. E., & Orlando, B. (2018). Diversity of board of directors and environmental social governance: Evidence from Italian listed companies. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 25(3), 250–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, C. M., & Dalton, D. R. (1994). Bankruptcy and corporate governance: The impact of board composition and structure. Academy of Management Journal, 37(6), 1603–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vasconcelos, I. F. F. G., Alves, M. A., & Pesqueux, Y. (2012). Responsabilidade social corporativa e desenvolvimento sustentável: Olhares habermasianos. Revista De Administração De Empresas, 52(2), 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eissa, A. M., Hamdy, A., & Diab, A. (2024). Governmental Ownership, board gender diversity, and ESG performance: Evidence from an emerging market. Sustainability, 16(16), 6963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament. (2020). Corporate social responsibility (CSR) and its implementation into EU company law. Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs, Directorate General for Internal Policies. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2020/658541/IPOL_STU(2020)658541_EN.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Pitman Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R. E., Dmytriyev, S. D., & Phillips, R. A. (2021). Stakeholder theory and the resource-based view of the firm. Journal of Management, 47(7), 1757–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannarakis, G. (2014). Corporate governance and financial characteristics affect the extent of corporate social responsibility disclosure. Social Responsibility Journal, 10(4), 569–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, F. A., Srinidhi, B., & Ng, A. C. (2011). Does board gender diversity improve the informativeness of stock prices? Journal of Accounting and Economics, 51(3), 314–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harjoto, M. A., & Wang, Y. (2020). Board of Directors network centrality and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance. Corporate Governance, 20(6), 965–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, A. J., Cannella, A. A., & Paetzold, R. L. (2000). The resource dependence role of corporate directors: Strategic adaptation of board composition in response to environmental change. Journal of Management Studies, 37(2), 235–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, A. J., Withers, M. C., & Collins, B. J. (2009). Resource dependence theory: A review. Journal of Management, 35(6), 1404–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, C. (2005). Why panel data? The Singapore Economic Review, 50(02), 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, C., Pesaran, M. H., & Tahmiscioglu, A. K. (2002). Maximum likelihood estimation of fixed effects dynamic panel data models covering short time periods. Journal of Econometrics, 109(1), 107–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husted, B. W., & de Sousa-Filho, J. M. (2019). Board structure and environmental, social, and governance disclosure in Latin America. Journal of Business Research, 102, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imbens, G., & Wooldridge, J. (2009). Recent developments in the econometrics of program evaluation. Journal of Economic Literature, 47(1), 5–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, A., & Hanaysha, J. R. (2023). Breaking the glass ceiling for a sustainable future: The power of women on corporate boards in reducing ESG controversies. International Journal of Accounting and Information Management, 31(4), 623–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, A., & Zaid, M. A. (2021). Boardroom gender diversity and corporate environmental performance: A multi-theoretical perspective in the MENA region. International Journal of Accounting & Information Management, 29(4), 603–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M., & Zhang, Z. (2012). Critical mass of women on BODs, multiple identities, and corporate philanthropic disaster response: Evidence from privately owned chinese firms. Journal of Business Ethics, 118(2), 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jizi, M. I., Salama, A., Dixon, R., & Stratling, R. (2014). Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility disclosure: Evidence from the US banking sector. Journal of Business Ethics, 125(4), 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanter, R. (1977a). Men and women of the corporation. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Kanter, R. M. (1977b). Some effects of proportions on group life: Skewed sex ratios and responses to token women. American Journal of Sociology, 82(5), 965–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khemakhem, H., Arroyo, P., & Montecinos, J. (2023). Gender diversity on board committees and ESG disclosure: Evidence from Canada. Journal of Management & Governance, 27(4), 1397–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoiriawati, N., & Nuswantara, D. A. (2021). Board characteristics and disclosure of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) Matters: Evidence from Asean countries. Review of business. Accounting, & Finance, 1(4), 374–391. [Google Scholar]

- Konrad, A. M., Kramer, V., & Erkut, S. (2008). Critical mass: The impact of three or more women on corporate boards. Organizational Dynamics, 37(2), 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulich, C., Ryan, M. K., & Haslam, S. A. (2007). Where is the romance for women leaders? The effects of gender on leadership attributions and performance-based pay. Applied Psychology, 56(4), 582–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurebwa, J., & Ndlovu, S. (2017). The critical mass theory and quota systems debate. International Journal of Advanced Research and Publications, 1(1), 48–55. Available online: http://www.ijarp.org/online-papers-publishing/july2017.html (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Kyaw, K., Olugbode, M., & Petracci, B. (2017). Can board gender diversity promote corporate social performance? Corporate Governance, 17(5), 789–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, L. L., & Heracleous, L. (2010). Rethinking agency theory: The view from law. Academy of Management Review, 35(2), 294–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P. M., & James, E. H. (2007). She’-e-os: Gender effects and investor reactions to the announcements of top executive appointments. Strategic Management Journal, 28(3), 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewellyn, K., & Muller-Kahle, M. (2023). ESG leaders or laggards? A configurational analysis of ESG performance. Business & Society, 63(5), 1149–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Gong, M., Zhang, X., & Koh, L. (2018). The impact of environmental, social, and governance disclosure on firm value: The role of CEO power. The British Accounting Review, 50(1), 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., & Fan, Y. (2023). Biased-sample empirical likelihood weighting for missing data problems: An alternative to inverse probability weighting. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B: Statistical Methodology, 85(1), 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Wei, Z. B., & Xie, F. X. (2014). Do women directors improve firm performance in China? Journal of Corporate Finance, 28, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, M., Mura, M., & Bonoli, A. (2005). Corporate social responsibility and corporate performance: The case of Italian SMEs. Corporate Governance, 5(4), 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y., Ahmad, M. I., & Torelli, R. (2024). Board gender diversity and ESG disclosure: The moderating role of audit committee. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 31(6), 5971–5983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, C., Koschnick, C., Brown, M., Ritschel, J. D., & Lucas, B. (2024). A panel data regression model for defense merger and acquisition activity. Journal of Defense Analytics and Logistics, 6(2), 122–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manita, R., Bruna, M. G., Dang, R., & Houanti, L. (2018). Board gender diversity and ESG disclosure: Evidence from the USA. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 19(2), 206–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, M. L., & Westphal, J. D. (2013). Access denied: Low mentoring of women and minority first-time directors and its negative effects on appointments to additional boards. Academy of Management Journal, 56(4), 1169–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, A., Hajdini, J., Iaia, L., De Luca, F., & Sakka, G. (2023). Stakeholder engagement and SDGs: The role of social media in the European context. EuroMed Journal of Business, 18(1), 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menicucci, E., & Paolucci, G. (2024). Board gender equality and ESG performance. Evidence from European banking sector. Corporate Governance, 24(8), 147–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, H., & Migliori, S. (2023). Effects of board gender diversity and sustainability committees on environmental performance: A quantile regression approach. Journal of Management & Organization, 29(6), 1051–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muoneke, O. B., Okere, K. I., & Egbo, O. P. (2023). Does political conflict tilt finance-renewable energy dynamics in Africa? Accounting for the multi-dimensional approach to financial development and threshold effect of political conflict. Heliyon, 9(3), e14155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T., Locke, S., & Reddy, K. (2015). Does boardroom gender diversity matter? Evidence from a transitional economy. International Review of Economics & Finance, 37, 184–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V. C., & Huynh, T. N. T. (2023). Characteristics of the board of directors and corporate financial performance—Empirical evidence. Economies, 11(2), 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S., & Huse, M. (2010). The contribution of women on boards of directors: Going beyond the surface. Corporate Governance an International Review, 18(2), 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orazalin, N., & Mahmood, M. (2021). Toward sustainable development: Board characteristics, country governance quality, and environmental performance. Business strategy and the environment, 30(8), 3569–3588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco, L. A., Vargas, J., & Galindo-Dorado, R. (2018). Trends on the relationship between board size and financial and reputational corporate performance. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, 27(2), 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagan, A. R., & Hall, A. D. (1983). Diagnostic tests as residual analysis. Econometric Reviews, 2(2), 159–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, C., Rahman, N., & McQuillen, C. (2015). From board composition to corporate environmental performance through sustainability-themed alliances. Journal of Business Ethics, 130(2), 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucheta-Martínez, M. C., & Bel-Oms, I. (2019). What have we learnt about board gender diversity as a business strategy? The appointment of board subcommittees. Business Strategy and the Environment, 28(2), 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, R., & Rajendran, C. (2020). Relating environmental, social, and governance scores and sustainability performances of firms: An empirical analysis. Business Strategy and the Environment, 29(3), 1247–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, P. R., & Rubin, D. B. (1983). The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika, 70(1), 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samara, G., Jamali, D., & Lapeira, M. (2019). Why and how should SHE make her way into the family business boardroom? Business Horizons, 62(1), 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz-Ziv, M. (2017). Gender and board activeness: The role of a critical mass. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 52(2), 751–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W. R., & Meyer, J. W. (1994). Institutional environments and organizations: Structural complexity and individualism. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Shaukat, A., Qiu, Y., & Trojanowski, G. (2016). Board attributes, corporate social responsibility strategy, and corporate environmental and social performance. Journal of Business Ethics, 135(3), 569–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, S. (2020). CEO inside debt and corporate social responsibility. International Journal of Managerial Finance, 16(4), 525–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, P., Chiang, S., & Wu, T. (2024). Board network and ESG performance: Evidence from China. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 31(6), 5709–5729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sila, V., Gonzalez, A., & Hagendorff, J. (2016). Women on board: Does boardroom gender diversity affect firm risk? Journal of Corporate Finance, 36, 26–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, J. H., & Yogo, M. (2005). Testing for weak instruments in linear IV regression. In D. W. K. Andrews, & J. H. Stock (Eds.), Identification and inference for econometric models: Essays in honor of Thomas Rothenberg (pp. 80–108). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Suttipun, M. (2021). The influence of board composition on environmental, social and governance (ESG) disclosure of Thai listed companies. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance, 18(4), 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terjesen, S., Sealy, R., & Singh, V. (2009). Women directors on corporate boards: A review and research agenda. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 17(3), 320–337. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10871/24385 (accessed on 5 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Toerien, F., Breedt, C., & De Jager, P. G. (2023). Does board gender diversity improve environmental, social and governance disclosure? Evidence from South Africa. South African Journal of Business Management, 54(1), 3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torchia, M., Calabrò, A., & Huse, M. (2011). Women directors on corporate boards: From tokenism to critical mass. Journal of Business Ethics, 102(2), 299–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasiuzzaman, S., & Subramaniam, V. (2023). Board gender diversity and environmental, social and governance (ESG) disclosure: Is it different for developed and developing nations? Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 30(5), 2145–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasiuzzaman, S., & Wan Mohammad, W. M. (2020). Board gender diversity and transparency of environmental, social and governance disclosure: Evidence from Malaysia. Managerial and Decision Economics, 41(1), 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R. J. (2003). Women on corporate boards of directors and their influence on corporate philanthropy. Journal of Business Ethics, 42(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wintoki, M. B., Linck, J. S., & Netter, J. M. (2012). Endogeneity and the dynamics of internal corporate governance. Journal of Financial Economics, 105(3), 581–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, J. M. (2012). Introductory econometrics: A modern approach. Nelson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q., Shahbaz, M., & Bigerna, S. (2024). Does board gender diversity benefit for corporate ESG performance: Evidence from Germany. Journal of Environmental Management, 372, 123304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P., & Prashar, A. (2022). Board gender diversity: Implications for environment, social, and governance (ESG) performance of Indian firms. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 72(9), 2654–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarram, S. R., & Adapa, S. (2021). Board gender diversity and corporate social responsibility: Is there a case for critical mass? Journal of Cleaner Production, 278, 123319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoder, J. D. (1991). Rethinking tokenism: Looking beyond numbers. Gender and Society, 5(2), 178–192. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/189483 (accessed on 5 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Yurtseven, C. (2015). The causes of electricity theft: An econometric analysis of the case of Turkey. Utilities Policy, 37, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaichkowsky, J. L. (2014). Women in the board room: One can make a difference. International Journal of Business Governance and Ethics, 9(1), 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, M. a. A., Wang, M., Adib, M., Sahyouni, A., & Abuhijleh, S. T. F. (2020). Boardroom nationality and gender diversity: Implications for corporate sustainability performance. Journal of Cleaner Production, 251, 119652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, R., Jain, T., Samara, G., & Jamali, D. (2020). Corporate governance meets corporate social responsibility: Mapping the interface. Business & Society, 61(3), 690–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y., & Chen, J. (2024). How does board gender diversity shape ESG performance? Finance Research Letters, 74, 106717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name of Variable | Definition | A Priori Expectation |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | ||

| ESG disclosure score | A combined disclosure score of an individual firm’s overall ESG transparency. It comprises the Environmental, Social, and Governance scores. | |

| Independent Variables | ||

| Critical mass | The dummy variable equals one if boards have at least three women directors on board and zero otherwise. | Positive |

| Token | The dummy variable is equal to 1 if the number of women directors on the board is 1 or 2 and 0 otherwise. | Negative |

| Blau index | Gender diversity on the board ranges from 0 to 0.5. | Positive |

| Shannon index | Gender diversity on the board ranging from 0 to 0.6. | Positive |

| Control variables | ||

| Board size | Board size is the total number of directors. | Positive |

| Board meetings per year | Number of board meetings per year. | Positive |

| Pct of independent directors | Percentage of independent or outside directors on the board. | Positive/Negative |

| CEO duality (CEO) | A dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the chairperson is also the CEO and 0 otherwise. | Positive/Negative |

| Financial leverage (FILV) | Financial leverage is the total debt divided by the firm’s total assets. | Positive |

| Tobin Q ratio | Tobin’s Q is calculated as the sum of the market value of equity, total liabilities, preferred equity, and minority interest divided by the value of total assets. | Positive/Negative |

| Firm size | Firm size is the natural log of the total assets of the firm. | Positive |

| GDP growth annual | Gross domestic product annual growth rate. | Positive/Negative |

| Industry dummies | A dummy variable for each industry to account for industry-specific fixed effects. One industry is established as the standard to circumvent the dummy variable trap. | |

| Year dummies | A dummy variable for each year from 2012 to 2023 to account for time-invariant effects. The year 2012 is chosen as the reference point to circumvent the dummy variable trap. | |

| Variables | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | p1 | p99 | Skew. | Kurt. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESG disclosure score | 534 | 58.108 | 10.083 | 18.408 | 83.613 | 36.133 | 80.223 | −0.0571 | 3.104 |

| Critical mass | 540 | 0.815 | 0.389 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | −1.621 | 3.627 |

| Token | 540 | 0.067 | 0.25 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3.474 | 13.071 |

| Blau index | 540 | 0.416 | 0.098 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 | −2.114 | 8.304 |

| Shannon index | 540 | 0.564 | 0.143 | 0 | 0.693 | 0 | 0.693 | −1.839 | 6.772 |

| Board size | 537 | 14.229 | 3.834 | 2 | 21 | 7 | 20 | −0.141 | 2.282 |

| Board meetings per year | 532 | 10.066 | 4.722 | 3 | 34 | 4 | 26 | 1.581 | 6.179 |

| Pct of independent directors | 524 | 65.67 | 21.216 | 20 | 100 | 20 | 100 | 0.193 | 2.226 |

| CEO duality | 537 | 0.251 | 0.434 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1.146 | 2.314 |

| Financial leverage | 536 | 7.053 | 8.478 | 1.355 | 70.363 | 1.388 | 32.072 | 3.055 | 17.51 |

| Tobin Q ratio | 535 | 1.826 | 1.51 | 0.831 | 12.032 | 0.899 | 7.453 | 3.05 | 13.876 |

| Firm size | 538 | 11.488 | 1.552 | 8.133 | 14.809 | 8.278 | 14.557 | 0.053 | 2.217 |

| GDP growth annual | 540 | 3.947 | 6.62 | −11.167 | 23.655 | −8.712 | 21.879 | 0.218 | 2.991 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) ESG disclosure score | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| (2) Token | −0.175 * | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| (0.000) | |||||||||||||

| (3) Critical mass | 0.338 * | −0.561 * | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | ||||||||||||

| (4) Blau index | 0.271 * | −0.281 * | 0.549 * | 1.000 | |||||||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |||||||||||

| (5) Shannon index | 0.283 * | −0.292 * | 0.556 * | 0.998 * | 1.000 | ||||||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | ||||||||||

| (6) Board_size | 0.075 | −0.304 * | 0.216 * | 0.077 | 0.071 | 1.000 | |||||||

| (0.085) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.075) | (0.102) | |||||||||

| (7) Firm size | 0.153 * | −0.107 * | 0.061 | 0.110 * | 0.115 * | 0.310 * | 1.000 | ||||||

| (0.000) | (0.013) | (0.161) | (0.011) | (0.007) | (0.000) | ||||||||

| (8) Financial leverage | −0.152 * | −0.040 | −0.042 | 0.045 | 0.044 | 0.050 | 0.585 * | 1.000 | |||||

| (0.000) | (0.361) | (0.331) | (0.298) | (0.305) | (0.247) | (0.000) | |||||||

| (9) Percentage of independent directors | −0.043 | 0.069 | −0.051 | 0.012 | 0.009 | −0.259 * | −0.062 | 0.059 | 1.000 | ||||

| (0.330) | (0.113) | (0.240) | (0.781) | (0.845) | (0.000) | (0.159) | (0.178) | ||||||

| (10) CEO duality | 0.090 * | −0.035 | 0.054 | 0.071 | 0.070 | −0.066 | −0.231 * | −0.258 * | −0.225 * | 1.000 | |||

| (0.038) | (0.416) | (0.211) | (0.101) | (0.104) | (0.126) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |||||

| (11) Board meetings | 0.203 * | 0.048 | −0.036 | 0.039 | 0.049 | −0.057 | 0.409 * | 0.312 * | 0.028 | −0.210 * | 1.000 | ||

| (0.000) | (0.272) | (0.402) | (0.366) | (0.260) | (0.190) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.522) | (0.000) | ||||

| (12) Tobin Q ratio | −0.070 | 0.036 | 0.045 | 0.067 | 0.066 | −0.246 * | −0.568 * | −0.289 * | −0.120 * | 0.093 * | −0.334 * | 1.000 | |

| (0.106) | (0.412) | (0.300) | (0.122) | (0.127) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.006) | (0.031) | (0.000) | |||

| (13) GDP growth annual | 0.180 * | 0.053 | −0.038 | 0.026 | 0.035 | −0.516 * | −0.104 * | −0.019 | 0.005 | 0.243 * | −0.026 | 0.182 * | 1.000 |

| (0.000) | (0.215) | (0.378) | (0.553) | (0.410) | (0.000) | (0.016) | (0.665) | (0.914) | (0.000) | (0.553) | (0.000) |

| Variables | VIF | 1/VIF |

|---|---|---|

| Firm size | 2.534 | 0.395 |

| Board size | 1.844 | 0.542 |

| Tobin Q ratio | 1.691 | 0.591 |

| Financial leverage | 1.627 | 0.615 |

| GDP growth annual | 1.488 | 0.672 |

| Board meetings per year | 1.337 | 0.748 |

| CEO duality | 1.289 | 0.776 |

| Percentage of independent directors | 1.246 | 0.803 |

| Token | 1.128 | 0.887 |

| Mean VIF | 1.576 | . |

| Variables | POOLED OLS | FIXED EFFECT | IV-GMM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Token | −3.1141 *** | −1.4666 | −8.83 *** | |||

| (−3.4744) | (−1.3946) | (3.229) | ||||

| Critical Mass | 2.8139 *** | 1.7514 ** | 10.31 *** | |||

| (2.6616) | (1.9742) | (3.345) | ||||

| Board Size | 0.4719 *** | 0.4872 *** | −0.3345 | −0.3307 | 0.241 | 0.348 |

| (3.5701) | (3.6526) | (−1.5955) | (−1.5857) | (0.223) | (0.220) | |

| Firm Size | 2.8203 *** | 2.8311 *** | 8.8968 *** | 8.8573 *** | 3.130 *** | 3.091 *** |

| (5.6371) | (5.6600) | (9.0636) | (9.0622) | (0.689) | (0.685) | |

| Financial Leverage | 0.0157 | 0.0153 | −0.0621 | −0.0663 | −0.131 | −0.0643 |

| (0.1574) | (0.1559) | (−0.8165) | (−0.8733) | (0.169) | (0.165) | |

| Percentage of Independent Directors | 0.0411 ** | 0.0412 ** | −0.0026 | −0.0035 | 0.0415 * | 0.0546 ** |

| (2.3593) | (2.3599) | (−0.1184) | (−0.1602) | (0.0238) | (0.0241) | |

| CEO Duality | 1.2523 | 1.1449 | −1.8830 * | −1.9274 ** | 1.498 | 2.015 * |

| (1.5125) | (1.3851) | (−1.9338) | (−1.9833) | (1.185) | (1.192) | |

| Board Meetings Per Yr | 0.4172 *** | 0.4234 *** | 0.0149 | 0.0072 | 0.451 *** | 0.502 *** |

| (5.5000) | (5.6261) | (0.1856) | (0.0897) | (0.106) | (0.103) | |

| Tobin Q Ratio | 0.5446 ** | 0.5608 ** | 1.7438 *** | 1.7568 *** | 0.557 * | 0.842 *** |

| (2.2049) | (2.2753) | (4.5376) | (4.5799) | (0.318) | (0.325) | |

| GDP Growth Annual | 0.3038 *** | 0.3098 *** | 0.4477 *** | 0.4231 ** | 0.261 *** | 0.218 ** |

| (4.1666) | (4.3001) | (2.6509) | (2.4975) | (0.100) | (0.102) | |

| Constant | 13.3993 ** | 10.0771 * | −42.172 *** | −43.219 *** | 14.46 ** | 1.920 |

| (2.5856) | (1.9137) | (−3.7794) | (−3.9303) | (6.935) | (7.567) | |

| Observations | 519 | 519 | 519 | 519 | 442 | 442 |

| R-squared | 0.5025 | 0.5031 | 0.4746 | 0.4768 | 0.426 | 0.410 |

| Industry dummies | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year dummies | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| First stage F-stat | 18.38 | 29.59 | ||||

| Kleibergen–Paap rk LM statistic | 18.56 | 23.90 | ||||

| Cragg–Donald Wald F statistic | 105.6 | 129.8 | ||||

| Hansen | 0.399 | 19.70 | ||||

| Hansen p-value | 0.528 | 9.06 × 10⁻⁶ | ||||

| Endogeneity test | 4.434 | 6.144 | ||||

| Endogeneity test p-value | 0.0352 | 0.0132 | ||||

| Number of cids | 45 | 45 | ||||

| Variables | FIXED EFFECT | IV-2SLS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Blau index | 15.5683 *** | 16.1782 *** | ||

| (4.4583) | (4.7633) | |||

| Shannon index | 11.1650 *** | 11.0177 *** | ||

| (4.6337) | (5.0319) | |||

| Board_size | −0.3617 * | −0.3495 * | −0.0611 *** | −0.0625 *** |

| (−1.8311) | (−1.7721) | (−2.625) | (−2.6452) | |

| Firm size | 7.0398 *** | 6.9277 *** | 0.0145 | 0.0136 |

| (7.3351) | (7.2065) | (0.9637) | (0.8862) | |

| Financial leverage | −0.0420 | −0.0399 | 0.0081 ** | 0.0079 ** |

| (−0.5809) | (−0.5541) | (2.3577) | (2.2864) | |

| Percentage of independent directors | −0.0049 | −0.0048 | −0.2803 | −0.3077 |

| (−0.2403) | (−0.2326) | (−1.4059) | (−1.5253) | |

| CEO duality | −1.7038 * | −1.6768 * | −0.0541 *** | −0.0544 *** |

| (−1.8433) | (−1.8167) | (−4.7669) | (−4.7205) | |

| Board meetings per year | −0.0232 | −0.0252 | −0.1847 *** | −0.1894 *** |

| (−0.3032) | (−0.3304) | (−3.3617) | (−3.3936) | |

| Tobin Q ratio | 1.7331 *** | 1.7293 *** | 0.0203 | 0.0164 |

| (4.7572) | (4.7556) | (0.2861) | (0.2284) | |

| GDP growth annual | 0.3813 ** | 0.3826 ** | −0.0099 | −0.0103 |

| (2.3862) | (2.3988) | (−0.8589) | (−0.8826) | |

| Constant | −26.1700 ** | −24.9049 ** | −1.7343 | −1.1432 |

| (−2.4258) | (−2.3101) | (−1.1405) | (−0.8159) | |

| Observations | 519 | 519 | 384 | 384 |

| Number of cid | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 |

| Country FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Durbin (score) chi2(1) | 19.8783 (p = 0.0000) | 23.9178 (p = 0.0000) | ||

| Wu–Hausman F (1364) | 19.8717 (p = 0.0000) | 24.178 (p = 0.0000) | ||

| First-stage F(1365)—Minimum eigenvalue statistic | 56.8606 (p = 0.0000) | 59.9802 (p = 0.0000) | ||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Industry: Consumer Discretionary | Industry: Consumer Staples | Industry: Energy | Industry: Financial | Industry: Health Care | Industry: Industrial | Industry: Information Technology | Industry: Utilities |

| Percentage of women on board | 0.147 ** | 0.122 ** | 0.414 * | 0.265 *** | 0.573 *** | 0.127 * | 0.420 *** | 0.073 |

| (2.276) | (2.295) | (1.885) | (4.416) | (4.054) | (1.724) | (3.304) | (0.644) | |

| Board size | 0.817 | −0.204 | 1.623 | −0.715 ** | 0.518 | −0.106 | 1.258 | −2.606 |

| (1.625) | (−0.430) | (0.730) | (−2.141) | (0.505) | (−0.206) | (1.521) | (−0.786) | |

| Firm size | 8.308 *** | 11.804 *** | 17.130 | 9.383 *** | 0.778 | 17.746 *** | −2.748 | 14.889 * |

| (3.434) | (4.249) | (0.961) | (2.847) | (0.244) | (5.488) | (−0.730) | (1.861) | |

| Financial leverage | −1.449 *** | −1.777 | 12.420 | 0.214 ** | 3.957 | −0.379 * | −3.725 | −4.09 *** |

| (−5.149) | (−0.658) | (1.032) | (2.467) | (0.917) | (−1.775) | (−1.612) | (−3.064) | |

| Percentage of independent directors | 0.041 | 0.035 | −0.419 | −0.007 | −0.054 | 0.192 *** | 0.180 | 0.085 |

| (1.090) | (0.219) | (−1.491) | (−0.154) | (−0.603) | (3.955) | (1.502) | (0.533) | |

| CEO duality | 3.992 | 1.907 | 10.886 | −5.035 ** | 0.478 | 0.307 | 9.181 | 2.606 |

| (0.904) | (1.003) | (1.112) | (−2.108) | (0.156) | (0.167) | (1.190) | (1.095) | |

| Board meetings per year | 0.292 * | 0.392 | −0.351 | −0.017 | −0.140 | 0.016 | −0.031 | −0.206 |

| (1.985) | (1.366) | (−0.329) | (−0.135) | (−0.302) | (0.059) | (−0.093) | (−1.049) | |

| Tobin Q ratio | 0.946 | 3.447 *** | 45.519 | 87.715 *** | −1.374 | 1.234 | 1.673 * | 7.044 |

| (1.479) | (2.769) | (0.961) | (2.826) | (−0.864) | (0.762) | (1.982) | (0.902) | |

| GDP growth annual | 3.236 *** | 0.610 | 0.048 | 0.326 * | −0.019 | −0.640 | 4.979 * | 4.880 ** |

| (3.195) | (1.499) | (0.066) | (1.670) | (−0.004) | (−1.653) | (1.999) | (2.509) | |

| Constant | −60.796 *** | −82.323 *** | −226.979 | −162.321 ** | 24.857 | −148.81 *** | 38.462 | −121.492 |

| (−2.808) | (−2.762) | (−1.033) | (−2.600) | (0.500) | (−4.326) | (1.267) | (−1.129) | |

| Observations | 104 | 59 | 24 | 131 | 36 | 94 | 47 | 24 |

| R-squared | 0.741 | 0.584 | 0.612 | 0.497 | 0.753 | 0.631 | 0.672 | 0.951 |

| Number of cids | 10 | 5 | 2 | 11 | 3 | 8 | 4 | 2 |

| Variables | FIXED EFFECT | IV 2SLS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Blau index | 8.629 *** | 34.326 *** | ||

| (4.231) | (4.839) | |||

| Shannon index | 5.673 *** | 23.457 *** | ||

| (4.011) | (4.975) | |||

| Board size | 0.329 *** | 0.333 *** | 0.250 * | 0.256 * |

| (2.855) | (2.879) | (1.648) | (1.692) | |

| Board average tenure | 0.276 ** | 0.277 ** | 0.348 ** | 0.359 ** |

| (2.108) | (2.117) | (2.028) | (2.094) | |

| Percentage of independent directors | 0.015 | 0.015 | −0.075 ** | −0.075 *** |

| (0.755) | (0.778) | (−2.558) | (−2.577) | |

| Financial leverage | −0.017 | −0.018 | −0.364 ** | −0.365 *** |

| (−0.408) | (−0.417) | (−9.721) | (−9.742) | |

| Firm size | 3.161 *** | 3.213 *** | 3.160 *** | 3.166 *** |

| (6.284) | (6.401) | (13.810) | (13.887) | |

| CEO duality | 0.818 | 0.712 | 2.458 | 2.104 |

| (0.552) | (0.480) | (1.012) | (0.876) | |

| Tobin Q ratio | 0.932 *** | 0.955 *** | 0.207 | 0.206 |

| (3.014) | (3.090) | (1.051) | (1.049) | |

| Constant | 7.161 | 6.884 | 11.552 *** | 12.374 *** |

| (1.473) | (1.416) | (3.808) | (4.179) | |

| Industry dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| F (1944) (Prob > F) | 242.079 (0.0000) | 262.046 (0.0000) | ||

| Cragg and Donald’s statistic | 242.079 | 242.079 | ||

| Durbin (score) chi2(1) (p-value) | 5.97392 (p = 0.0145) | 6.15837 (p = 0.0131) | ||

| Wu–Hausman F (1943) | 5.88022 (p = 0.0155) | 6.06294 (p = 0.0140) | ||

| Pagan–Hall general test (p-value) | 75.800 (0.0000) | 77.229 (0.0000) | ||

| Observations | 964 | 964 | 964 | 964 |

| R-squared | 0.632 | 0.631 | 0.480 | 0.481 |

| T-values are in parentheses. | ||||

| ESG Disclosure Score | Coefficient | Standard Error | Z-Statistics | p > |z| |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATET Female CEO or equivalent | ||||

| (1 vs. 0) | 2.752011 | 1.016004 | 2.71 | 0.007 |

| POmean Female CEO or equivalent | ||||

| 0 | 53.68396 | 0.6528433 | 82.23 | 0.000 |

| Number of obs = 964 Outcome model: weighted mean Treatment model: logit |

| Test Description | Change Applied | Key Finding | Table Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative Board Gender Diversity Measures | Employed various metrics to measure gender diversity (Blau and Shannon index) | Finding remains consistent | Table 6 |

| Cross-Industry Comparison | Analysed gender diversity and ESG disclosures across several industries | Finding remains consistent across all industries | Table 7 |

| Alternative Market Sample | Focused on UK FSTE 100 (2012–2023) | Main finding persists | Table 8 |

| Alternative technique | Applied inverse probability weighting (IPW) regression | Results are robust to methodological change | Table 9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Omenihu, C.M.; Abdrakhmanova, M.; Koufopoulos, D.N. Board Gender Diversity and Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Disclosure in Developed Countries. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15040141

Omenihu CM, Abdrakhmanova M, Koufopoulos DN. Board Gender Diversity and Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Disclosure in Developed Countries. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(4):141. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15040141

Chicago/Turabian StyleOmenihu, Chinonyerem Matilda, Madina Abdrakhmanova, and Dimitrios N. Koufopoulos. 2025. "Board Gender Diversity and Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Disclosure in Developed Countries" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 4: 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15040141

APA StyleOmenihu, C. M., Abdrakhmanova, M., & Koufopoulos, D. N. (2025). Board Gender Diversity and Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Disclosure in Developed Countries. Administrative Sciences, 15(4), 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15040141