1. Introduction

Supply chain management (SCM) has emerged as a strategic approach to enhancing organizational performance (OP) and gaining a competitive advantage in an era where global business competition has shifted from individual firms to entire supply chains (

Attia & Salama, 2018). This shift is driven by factors such as global sourcing, increasing quality and time-based competition, and growing environmental uncertainty (

Dahinine et al., 2024). Additionally, heightened concerns over climate change and sustainability have influenced customer preferences, compelling corporations to adopt environmentally sustainable practices and comply with global environmental standards (

De et al., 2020;

Iqbal et al., 2022;

Jum’a et al., 2021). Scholars have emphasized that organizations with strong environmental sustainability performance (ESP) benefit from improved reputations, brand equity, and market positioning, reinforcing the importance of integrating sustainability into SCM strategies (

Al-Sheyadi et al., 2019;

Rasheed et al., 2023).

To achieve efficient SCM, firms must implement effective supply chain management practices (SCMPs), which include a set of coordinated activities aimed at optimizing supply chain efficiency and performance (

Li et al., 2006). Prior studies highlight that SCMPs enhance logistics operations, supply chain (SC) efficiency, and overall firm performance (

Fredendall et al., 2016;

Gandhi et al., 2017). Additionally, SCMPs contribute positively to ESP by fostering resource optimization and minimizing environmental footprints (

Jum’a et al., 2021;

Rasheed et al., 2023).

Consequently, SCMPs should be designed to achieve dual objectives: strengthening OP by enhancing supply chain competitiveness and addressing environmental responsibilities through sustainable business practices (

Le, 2020). Moreover, stakeholders’ concerns regarding the environmental impact of production activities have driven firms to integrate green initiatives into their supply chains (

Jum’a et al., 2023). With increasing consumer awareness of issues such as resource depletion and carbon emissions, companies are adopting sustainable practices, including a reduced reliance on fossil fuels and greener supply chain strategies (

Yosef et al., 2023;

Jum’a, 2023).

In dynamic business environments, supply chains must adapt to external pressures, such as legal, social, economic, and political changes, to maintain competitiveness. Supply chain resilience, characterized by flexibility and responsiveness, plays a crucial role in achieving this adaptability (

Boute et al., 2012;

Isnaini et al., 2020). Contingency theory posits that firms face varying degrees of uncertainty and must tailor their strategies accordingly, emphasizing the importance of context-specific SCMP implementation (

Gingersberg & Venkatraman, 1985;

Lee et al., 2016). Among the factors influencing SC effectiveness, supply chain dynamism (SCD) is particularly relevant, as it represents the rate of unpredictable changes within supply chain elements (

Billah et al., 2023). Understanding the moderating role of SCD in SCM-performance relationships can provide deeper insights into how firms navigate external uncertainties.

Despite the recognized benefits of SCM, research on SCMPs has been largely concentrated in developed economies, overlooking their impact in developing countries where SCM adoption is still evolving (

M. G. M. Yang et al., 2011;

Yosef et al., 2023;

Jum’a et al., 2024). Many multinational corporations have relocated their manufacturing operations to developing nations to capitalize on lower labor costs and tax incentives (

Coyle et al., 2015;

Tukamuhabwa et al., 2017). However, while these regions contribute significantly to global supply chains, studies on SCMPs in these contexts remain limited (

Lautier, 2024;

Wan et al., 2022). Addressing this research gap is crucial for developing tailored SCM strategies that account for the specific challenges and opportunities faced by firms in these regions.

The manufacturing sector is a key pillar of Jordan’s economy, contributing approximately 17.3% of GDP and serving as the second-largest economic driver after the service sector (

Jordan Chamber of Industry, 2023). Export-oriented firms, particularly those in the Garment, Textile, and Leather (GTL) sector, play a critical role in the country’s economic growth (

Ramadhani et al., 2018). Despite competition from other industries, such as chemicals, mining, and agriculture, the GTL sector has remained a dominant force, surpassing JOD 1.4 billion in export value in recent years (

Jordan Chamber of Industry, 2023). Moreover, the sector aligns with green trade principles, enhancing its attractiveness to investors. Government-driven initiatives, such as the establishment of Qualified Industrial Zones (QIZs), have further pressured firms to adopt improved SCMPs to maintain competitiveness (

Holzberg, 2023). However, research indicates that SCM adoption in Jordan remains limited, with many firms lacking awareness and the implementation of effective SCMPs (

Alzubi & Akkerman, 2022). Furthermore, studies on sustainability improvements highlight the need for policies that promote sustainable manufacturing technologies, particularly in developing economies (

Montiel-Hernández et al., 2024;

Jum’a et al., 2024;

Yosef et al., 2023).

Given this context, there is a critical need to examine how SCMPs contribute to both OP and ESP in Jordan’s GTL sector. This study fills a significant research gap by investigating the effectiveness of SCMPs in a developing economy, offering insights into how these practices influence performance outcomes under varying levels of SCD. Specifically, this research addresses the following research questions: (1) How do SCMPs influence OP? (2) How do SCMPs impact ESP? (3) Does SCD moderate the relationship between SCMPs and OP/ESP?

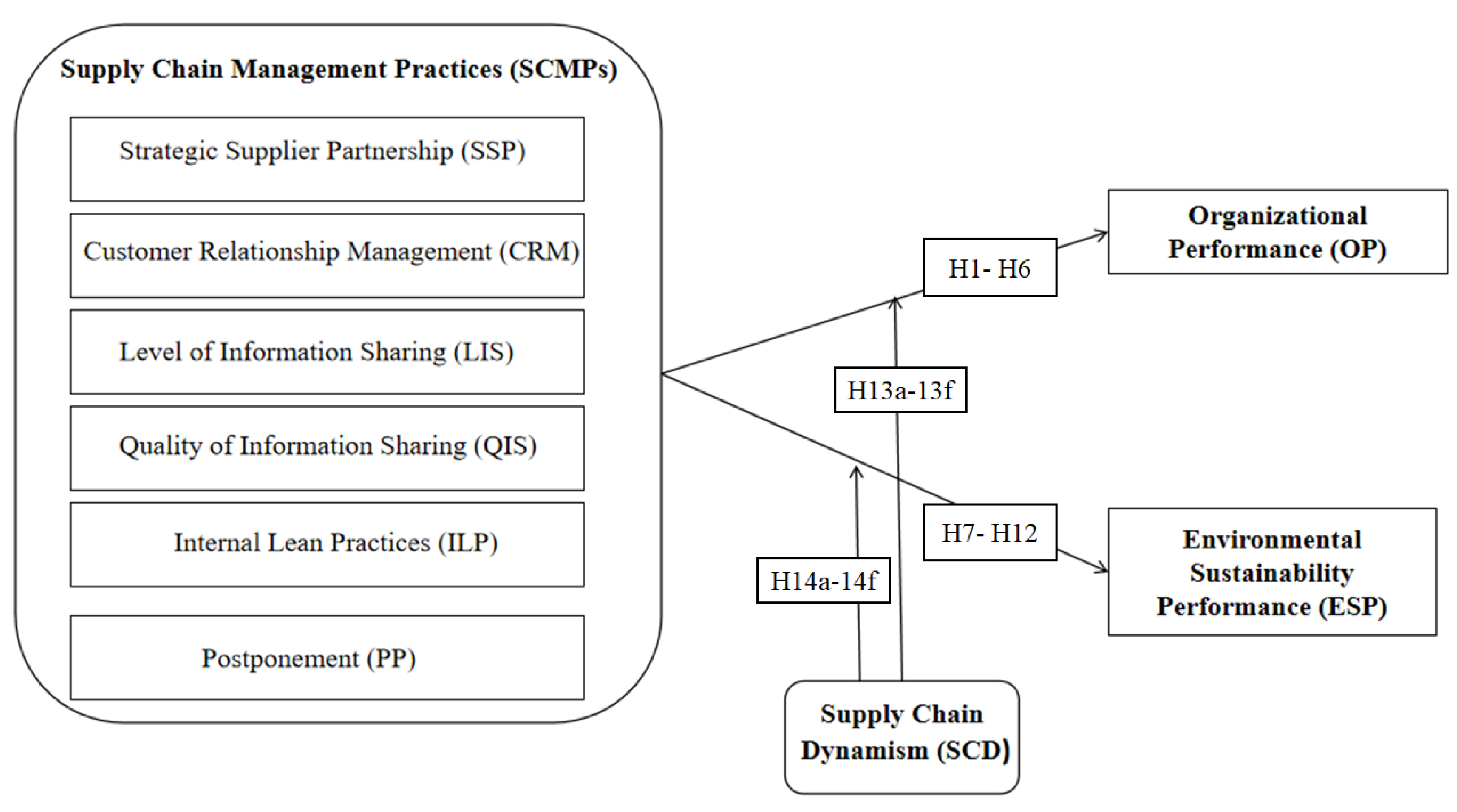

This study’s novelty lies in its examination of six key SCMPs—strategic supplier partnership (SSP), customer relationship management (CRM), internal lean practices (ILPs), level of information sharing (LIS), quality of information sharing (QIS), and postponement (PP)—within Jordan’s export-oriented GTL sector. By integrating SCD as a moderating variable, this research extends contingency theory and provides empirical evidence on how external uncertainties shape SCM–performance relationships.

Unlike previous studies that primarily focus on developed economies, this study contextualizes SCM practices in a developing market, offering a holistic framework for building resilient and sustainable supply chains. The findings contribute to both the academic literature and managerial practice, equipping supply chain professionals with actionable strategies to optimize performance in dynamic business environments.

This paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 represents a literature review from which the research objectives, questions, hypotheses, and conceptual model were developed.

Section 3 includes the research methodology, whereas the findings and discussion are represented in

Section 4. Finally, in

Section 5, the study’s conclusion, future recommendations, and limitations are represented.

4. Results and Discussion

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was conducted using SmartPLS version 4 to evaluate the proposed conceptual model and hypotheses, as detailed by

Sarstedt et al. (

2021) and

Richter et al. (

2016). The measurement model analysis stage involved employing various techniques, including a demographic analysis, descriptive statistics, validity and reliability assessments, and tests for multicollinearity.

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

To analyze the data, composite scores were calculated for each latent construct by combining the responses to their respective measurement items, as shown in

Table 5. CRM recorded the highest mean score (M = 4.03; SD = 0.794), as shown in

Table 5, reflecting strong positive feedback. Conversely, SCD had the lowest mean score (M = 3.16; SD = 0.980). The remaining variables reported mean scores falling between these two extremes.

4.2. Multicollinearity Diagnosis

Multicollinearity develops when one predictor variable has a direct relationship with another set of predictor variables. The variance inflation factor (VIF) is a metric used to detect multicollinearity in independent variables. According to

Hair et al. (

2019), the VIF should be less than 5. The findings confirm that all VIF values met these criteria, indicating the absence of significant multicollinearity, as demonstrated in

Table 6.

4.3. Scale Validity and Reliability

Factor loadings and the Average Variance Extracted (AVE), along with Discriminant Validity, assessed through the Fornell and Larcker criterion, were utilized to validate the constructs. Internal reliability was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha and Composite Reliability (CR). According to

Hair et al.’s (

2019) guidelines, factor loading values for the measurement items should exceed 0.70, and AVE values should be above 0.50 for the constructs to be considered valid. Additionally, all Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability values must surpass the 0.70 threshold to be deemed acceptable. As demonstrated in

Table 7, the independent variables used in this study were confirmed to be both valid and reliable. Discriminant validity is confirmed when the square root of AVE exceeds the corresponding inter-construct correlations. The results, as shown in

Table 8, validate the discriminant validity of the constructs, demonstrating that each construct is distinct and measures a unique aspect of the model.

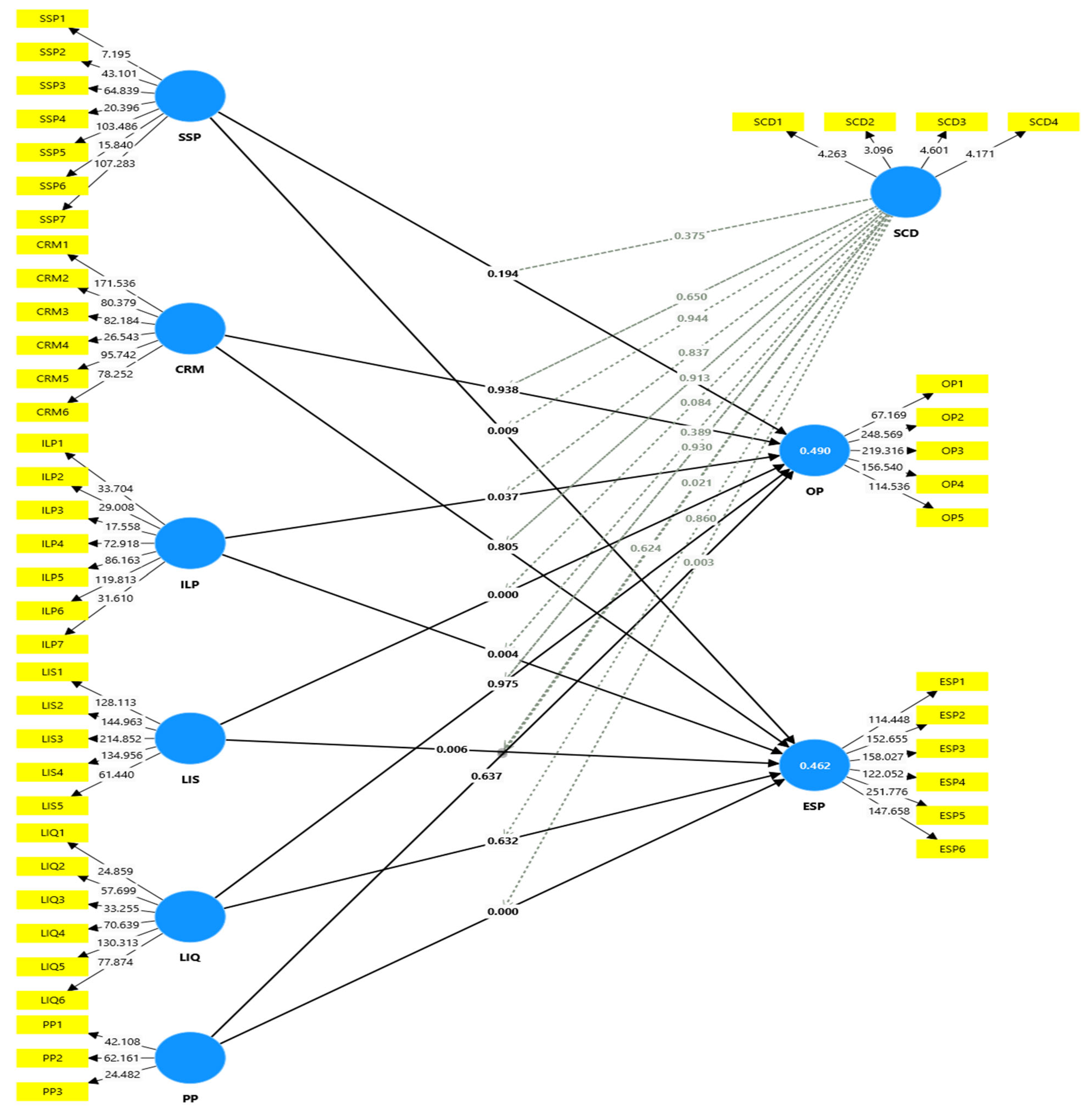

The findings indicate an SRMR of 0.063 and an NFI of 0.819, indicating that the model was well-fitted, as SRMR values less than 0.09 and NFI values greater than 0.80 are generally considered acceptable (

Hair et al., 2019). The links between the constructs’ hypotheses and predictive ability assessments are being studied. The structural model in SmartPLS was executed using the bootstrapping method with 5000 sub-samples, as shown in

Figure 2. The analysis determined that the model is responsible for approximately 59% of the variance in OP and 56.2% of the variance in ESP.

This figure illustrates the structural relationships between SCMPs, OP, ESP, and the moderating role of SCD. The path coefficients and significance levels highlight that LIS and ILPs have the strongest positive effects on both OP and ESP, while PP is significantly moderated by SCD. These results visually reinforce the statistical findings, providing a clearer understanding of the key relationships within the model.

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

The findings from the direct and indirect hypotheses of the conceptual model are presented in

Table 9. Among the hypotheses tested, several were accepted based on their statistically significant

p-values (≤0.05). Specifically, hypotheses H3 (LIS -> ESP;

p = 0.006); H5 (ILPs -> OP;

p = 0.037); H7 (SSP -> ESP;

p = 0.009); H9 (LIS -> ESP;

p = 0.006); H11 (ILPs -> ESP;

p = 0.004); and H12 (PP -> ESP;

p = 0.000) demonstrated significant relationships between their respective constructs. Conversely, hypotheses H1 (SSP -> OP;

p = 0.194); H2 (CRM -> ESP;

p = 0.805); H4 (QIS -> OP;

p = 0.975); H6 (PP -> OP;

p = 0.637); H8 (CRM -> OP;

p = 0.938); and H10 (QIS -> ESP;

p = 0.632) were rejected due to non-significant

p-values. Furthermore, this study revealed that among all SCMPs, LIS had the most substantial impact on OP, evidenced by a T statistic of 6.935. Additionally, PP emerged as having the most significant impact on ESP among SCM practices, with a T statistic of 3.727.

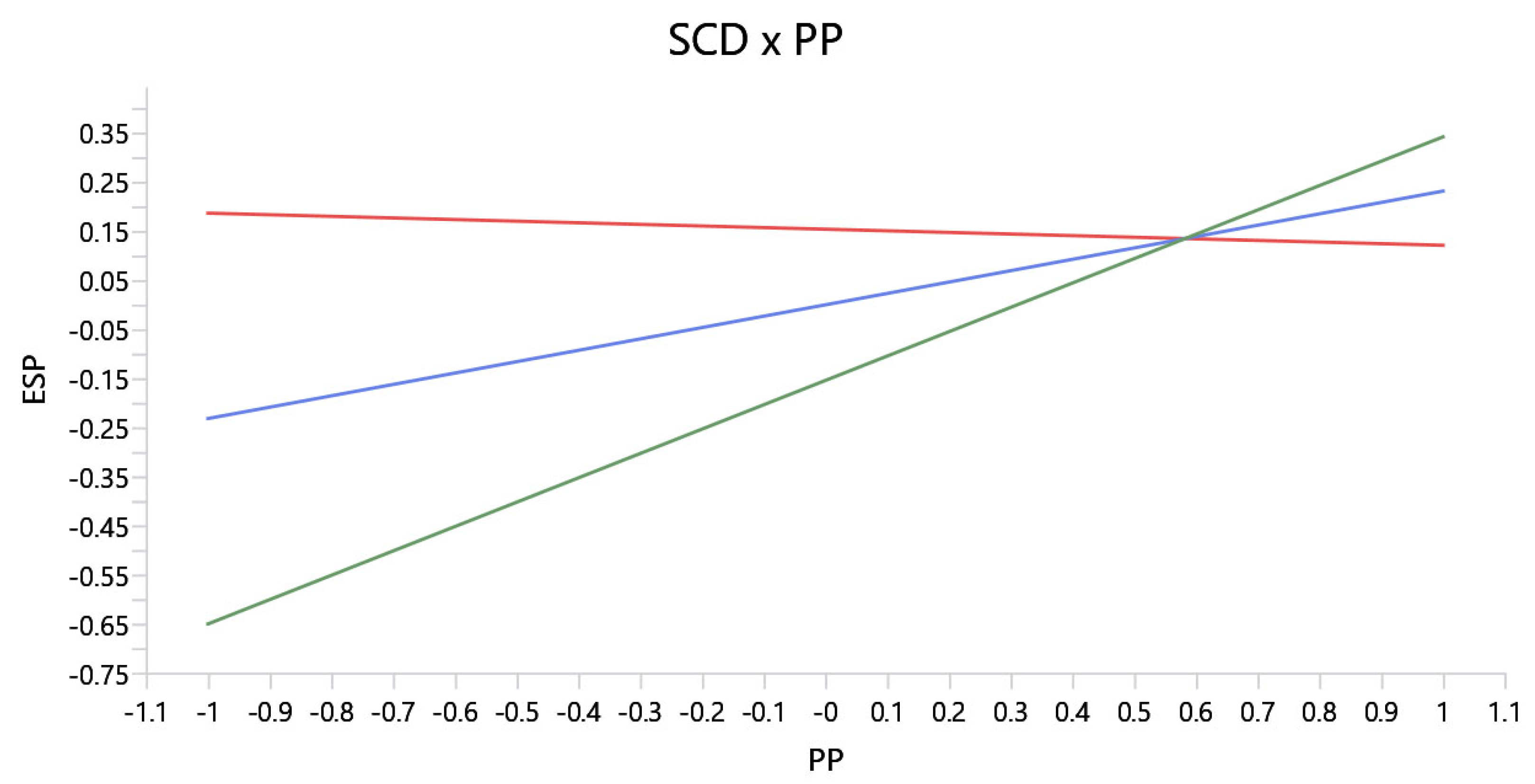

Regarding the moderation impact, SCD was tested between overall SCM practices and OP/ESP. Results show that hypotheses H13f (p = 0.021) and H14f (p = 0.003) were accepted due to significant p-values. Therefore, this study revealed a significant moderation effect of SCD on the relationship between PP and OP/ESP.

The moderation analysis revealed that SCD had a significant moderating effect only on the relationship between PP and both OP and ESP, while its interaction with other SCMPs did not yield significant results. A slope analysis for the moderating effect of SCD on the relationship between PP and both OP and ESP revealed that at higher levels of SCD, the positive impact of PP on performance outcomes is more pronounced. This suggests that in highly dynamic supply chain environments, firms that adopt PP strategies experience greater improvements in OP and ESP compared to those operating in more stable conditions, as shown in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4.

4.5. Discussion

The results show that SSP and CRM, as proposed in H1 and H2, respectively, did not significantly affect OP, contradicting the findings of several prior studies. For instance,

Hejazi (

2022) emphasized that OP is positively influenced by both SSP and CRM. Similarly,

Al-Madi et al. (

2021),

Hashim et al. (

2020), and

Utami et al. (

2019) reported these practices as critical contributors to OP success.

The differing results for SSP and CRM on OP may stem from the nature of the export-oriented firms operating under the QIZ agreements in Jordan, where key decisions are heavily influenced by foreign purchasers. This limits firms’ autonomy in SSP and CRM, potentially restricting their impact on OP. Additionally, according to

Danese and Romano (

2011) and

Yusuf and Shehu (

2017), the impact of customer integration on organizational performance may vary, depending on the amount of supplier integration. This comment stresses this study’s findings, which reveal a negligible association between SSP and OP.

In contrast, the results show that OP is significantly influenced by LIS, as formulated in H3. This finding aligns with those of

Jum’a et al. (

2021) and

Salleh (

2017), who concluded that higher levels of information sharing enhance supply chain visibility, enable better planning, and optimize resources, thereby contributing to better business performance and a competitive advantage. Although OP was positively influenced by the quantity aspect of information (LIS), the results show that QIS, as claimed in H4, did not exhibit a significant impact on OP, deviating from the findings of

Hassan (

2023) and

Keawkunti et al. (

2020). This suggests that when firms lack access to high-quality, timely, and reliable data, their ability to drive operational improvements may be reduced, thereby diminishing the impact of QIS on performance.

Regarding the impact of internal practices on OP, ILPs, as claimed in H5, demonstrated positive performance outcomes, aligning with the findings of

Hashim et al. (

2020) and

Khalil et al. (

2019). In contrast, PP, as predicted in H6, showed no significant impact on OP. Although postponement is designed to manage risks by delaying final product assembly until customer orders are received, this approach did not lead to performance improvements. One possible explanation for this result is the need for higher levels of education and expertise for effective implementation, as highlighted by

Hussain et al. (

2014). Moreover, since firms operate under rigid buyer-driven models, the potential benefits of postponement may not be translated into improvements in organizational performance.

In the context of ESP, the results show that SSP, as claimed in H7, revealed a significant positive relationship with ESP. SSP can reduce waste, save energy, and enhance environmental outcomes through effective collaboration and knowledge sharing, as claimed by the findings of

Bandehnezhad et al. (

2012) and

Iranmanesh et al. (

2019).

CRM, as proposed in H8, was found to have no significant impact on ESP in this study. These findings are inconsistent with those of

Jum’a et al. (

2021) and

Iranmanesh et al. (

2019), who identified CRM as a significant contributor to ESP. This could be attributed to the fact that sustainability policies are dictated by buyers and enforced externally through supplier selection rather than direct customer engagement, thereby limiting the impact of CRM on sustainability efforts.

This study also found that LIS, as predicted in H9, significantly influences environmental outcomes. These results are consistent with

Jum’a et al. (

2021), who concluded that LIS facilitates accurate demand forecasting, reducing waste and overproduction, thereby contributing to improved environmental performance.

QIS, as claimed in H10, was found to have an insignificant impact on ESP. According to

Li et al. (

2006), longer and more complex supply chains are prone to information distortion, which can negatively impact information quality. This complexity in the GTL supply chain could also explain the discrepancies in QIS’s influence on ESP observed in this study.

This study reveals that ESP is positively influenced by both ILPs and PP, as predicted in H11 and H12, respectively. The findings align with those of

Bandehnezhad et al. (

2012) and

Iranmanesh et al. (

2019), who emphasized that adopting lean practices is critical for achieving environmental benefits. While firms may not experience performance improvements from PP in terms of OP, this practice can still enhance ESP by ensuring compliance with global sustainability requirements and reducing environmental impacts. The positive effect of PP is further supported by

B. Yang et al. (

2005), who highlighted that postponement minimizes excessive inventory in the early supply chain stages, preventing overproduction, reducing waste, conserving energy, and aligning with sustainable business practices.

This study shows insignificant results for supply chain dynamism on organizational or environmental performance in the Jordanian GTL sector. The SCD items capture volatility in customer preferences, process changes, and competitive dynamics. Unlike industries with greater autonomy, many strategic decisions for major export-oriented enterprises operating under QIZ agreements are heavily influenced by the specifications and criteria of foreign purchasers, limiting the direct influence of supply chain dynamism on performance outcomes. Therefore, these fluctuations do not necessarily lead to improved performance. The absence of a significant link between SCD and ESP further suggests that environmental sustainability efforts in this sector are not internally driven.

The indirect impact of SCD as a moderator between SCMPs and both OP and ESP showed inconsistent results compared to previous studies (

Ali et al., 2024;

Isnaini et al., 2020;

Lee et al., 2016;

Billah et al., 2023). Among the six practices, only PP was moderated by SCD, influencing both OP and ESP, as claimed in H13f and H14f, respectively. This suggests that in the GTL sector, not all SCMPs benefit from dynamism. Instead, practices that inherently offer flexibility, like PP, become more critical as supply chain uncertainty increases.

The findings indicate that as SCD rises, flexible practices, like PP, become more important. PP enhances OP and ESP in dynamic environments by allowing firms to delay production and final assembly based on real-time demands. Despite this sector’s nature, PP serves as an adaptive mechanism, helping firms manage external uncertainties while maintaining compliance with buyer expectations. This explains why SCD strengthens PP’s impact on performance, even though SCD alone does not directly improve OP or ESP.

5. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This study makes several important theoretical contributions to the field of SCM by providing a nuanced understanding of how SCMPs influence both ESP and OP, particularly in the context of a developing economy. While prior research has predominantly focused on developed markets, this study addresses a critical gap by examining SCMPs within Jordan’s export-oriented GTL sector, offering valuable insights into the unique challenges and opportunities faced by firms in this setting. By analyzing six key SCMPs, this study enhances theoretical perspectives on their differential impact on performance outcomes, revealing that not all practices contribute equally to OP and ESP.

Additionally, this study advances contingency theory by exploring the moderating role of SCD in shaping the effectiveness of SCMPs. The findings indicate that SCD significantly moderates the relationship between PP and both OP and ESP, highlighting the importance of adaptability in highly dynamic supply chain environments. This contributes to the theoretical discourse on supply chain resilience, demonstrating that firms operating in volatile markets can achieve greater performance benefits by strategically leveraging postponement. This study also challenges conventional assumptions by showing that SCD does not significantly moderate other SCMPs, suggesting that some practices remain stable in their impact regardless of environmental uncertainty.

Moreover, this research extends the literature on sustainable SCM by emphasizing the dual objectives of economic competitiveness and environmental responsibility. It reinforces the growing recognition that integrating sustainability into supply chain strategies is not only a regulatory or ethical necessity but also a performance-enhancing factor within the GTL sector in Jordan.

5.2. Practical Implications

SC managers must actively drive firms toward stronger environmental sustainability commitments by integrating structured implementation strategies. The findings highlight that LIS significantly enhances both OP and ESP, emphasizing the need for firms to establish real-time data-sharing mechanisms and transparent communication channels across the supply chain. To achieve this, firms should invest in digital solutions, such as cloud-based SCM platforms, blockchain for traceability, and AI-driven analytics, ensuring seamless and accurate information flow. Additionally, training programs for employees on data management and digital tools should be prioritized to enhance LIS capabilities and improve decision-making efficiency.

ILPs also play a crucial role in improving OP and ESP by streamlining internal processes and minimizing waste. Manufacturers should adopt lean methodologies, such as JIT inventory systems, kaizen initiatives, and cross-functional team collaboration, to optimize production efficiency and sustainability. Implementing energy-efficient production techniques, automation in material handling, and waste reduction initiatives will further enhance operational performance while supporting environmental goals.

Moreover, PP was found to significantly influence OP and ESP when moderated by SCD, suggesting its effectiveness in high-velocity, high-uncertainty industries, like fast-moving consumer goods. To leverage PP effectively, managers should implement flexible production systems, late-stage customization, and demand-driven inventory replenishment strategies to minimize risks associated with market volatility. Investing in modular production systems and digital twins for real-time scenario planning can further enhance firms’ ability to adapt to fluctuating demand conditions.

In addition, the negative impact of SSP on OP suggests that while sustainable supplier partnerships can drive long-term environmental benefits, they may not immediately enhance operational outcomes. Firms should engage suppliers in joint sustainability initiatives, such as green material sourcing, waste reduction programs, and carbon footprint monitoring, to ensure that sustainability efforts align with supply chain efficiency. Supplier evaluation metrics should incorporate ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) compliance standards, ensuring that sustainability-driven partnerships also contribute to long-term performance improvements.

Furthermore, the findings indicate that CRM and QIS do not significantly impact OP or ESP, suggesting that these practices require strategic realignment. Firms should redefine their CRM strategies to better integrate sustainability objectives, focusing on customer engagement initiatives that promote eco-friendly products and responsible consumption. For QIS, firms must enhance data accuracy and relevance through advanced data validation techniques and AI-driven quality assessments, ensuring that shared information adds real value to supply chain decision-making.

Finally, firms must move beyond viewing SCD as merely a performance determinant and instead adopt adaptive supply chain strategies to mitigate environmental volatility. Given the moderating role of SCD on PP, firms should develop resilient supply chain models incorporating predictive analytics, scenario-based risk management, and agile response systems. Leveraging IoT-enabled monitoring, digital supply networks, and responsive logistics strategies will allow companies to proactively adjust to environmental uncertainties, improve decision-making, and align supply chain operations with sustainability goals.

6. Conclusions, Future Research, and Limitations

The results of this research indicate that two dimensions, LIS and ILPs, have a dual positive and significant impact on organizational and environmental outcomes. These findings suggest that manufacturing firms aiming to excel in both economic and environmental aspects should focus on prioritizing these practices into their operations. Based on the findings, given the enormous benefits of ILPs and LIS for OP, future research should investigate the specific processes by which these activities improve performance in various circumstances. Furthermore, PP requires more flexibility in response to external changes, as its effectiveness in enhancing organizational and sustainability performance was moderated in a highly dynamic environment.

Future research should enhance the generalizability of the findings by adopting probability sampling methods, such as simple random sampling, stratified sampling, or cluster sampling, to ensure a more representative sample of firms across different sectors and regions. This approach would provide a broader perspective on the impact of SCMPs on OP and ESP, making the results more applicable to diverse business environments. Additionally, given that this study relies solely on quantitative data, future research should incorporate qualitative approaches, such as in-depth interviews or case studies, to explore the contextual factors influencing SCMP adoption and effectiveness. This mixed-methods approach could uncover managerial perspectives, industry-specific challenges, and best practices that are not easily captured through survey data.

Moreover, while this study focuses on environmental outcomes within ESP, sustainability is a multidimensional construct that also includes social and economic factors. Future research should consider integrating these dimensions to provide a more holistic view of sustainability performance. For instance, examining how SCMPs contribute to social responsibility initiatives, fair labor practices, or economic resilience would offer a more comprehensive understanding of their long-term impact. Researchers could also explore the role of government policies, market regulations, and industry-specific sustainability standards in shaping firms’ supply chain strategies.

Furthermore, longitudinal studies could provide valuable insights into the long-term effects of SCMPs on performance outcomes, allowing researchers to track changes over time and assess the sustainability of implemented practices. Future research should also examine the moderating role of technological advancements, such as artificial intelligence, blockchain, and the Internet of Things (IoT), in optimizing supply chain processes and enhancing sustainability performance. These practical recommendations would help bridge the gap between theory and real-world applications, offering valuable insights for both academics and practitioners in the field of supply chain management.