Abstract

To understand how telework is perceived among occupational groups with different work tasks within the same company, this qualitative study aimed to explore how managers and employees experience telework in relation to well-being, individual performance, and the work environment. This qualitative study used a phenomenographic approach. Fourteen online interviews, comprising seven managers and seven employees from the same industrial company, were conducted between February 2022 and September 2023. The data were analyzed inductively to capture variations in telework perceptions. The findings showed that telework is not universally beneficial or challenging; its effectiveness depends on contextual factors such as team setting, job role, type of work, and organizational culture. Telework benefits both employees and managers engaged in individual tasks (e.g., reading, drafting contracts, and preparing reports) or global collaborations, including improved well-being, work–life balance, and overall performance. However, starting with an office-based period that facilitated team cohesion, faster learning, and a deeper understanding of the organizational culture. Face-to-face onsite work could be time-consuming and, therefore, stressful for some, but it is time-saving for others. Onsite employees and managers faced increased workloads when colleagues teleworked, as employees tended to rely more on colleagues physically present in the office. This research highlights the need for tailored strategies to enhance the advantages of telework while reducing its challenges. It contributes to existing research by providing nuanced insights into the relationship between telework and occupational groups within an industrial setting and offering practical guidance for telework in this field.

1. Introduction

Telework is a work arrangement in which employees and managers are not located at a central work site but rather work at a distant location—for example, from home or shared office space (Eurostat, 2023; Lunde et al., 2022), and has become an essential work-related issue for organizations since the COVID-19 pandemic (Chu et al., 2022). In 2022, nearly 15 percent of employees in Sweden worked from home for at least 2.5 days per week (Statistikmyndigheten [Statitics Sweden], 2023). In comparison, approximately 11 percent of employees in Europe occasionally worked from home in 2022 (Eurostat, 2023). In the USA, approximately 40 percent of employees teleworked in 2022 (Barrero et al., 2023). Most of them followed a hybrid work arrangement: they worked some days at the workplace and some days at home (Barrero et al., 2023). The proportion and frequency of telework differ across occupational groups in Sweden (Statistikmyndigheten [Statitics Sweden], 2023). Telework is most common among professions requiring a high level of education (tertiary education), with 26 percent working from home at least 50 percent of their working time (Statistikmyndigheten [Statitics Sweden], 2023).

The shift to telework for many employees during the pandemic has now become a preference for most employees, with many opting for part-time or full-time telework (Predotova & Vargas Llave, 2021). According to a recent survey conducted in the USA (Reiter-Palmon et al., 2021), 75% of the respondents would rather work from home or in a hybrid setting, and one-third indicated that they might seek a new job if forced to return to the office full-time (Reiter-Palmon et al., 2021). The employees’ preference for telework highlights its potential to retain talent. Previous studies have shown that telework can contribute to a better focus with fewer distractions, increased job autonomy, flexibility to work around life commitments, and better well-being (Adamovic, 2022; Kaplan et al., 2018). According to Mutiganda et al. (2022) and Beckel and Fisher (2022), telework can improve individual and organizational performance and reduce employee turnover and costs for the organization. Telework and flexibility can also be sources of competitive advantages for organizations (Antunes et al., 2023).

According to Vayre et al. (2022), setting boundaries for work, work-based relationships, and socio-professional integration can be negatively affected by teleworking. Furthermore, teleworkers’ physical separation from work colleagues can lead to isolation and exclusion from the work organization, negatively affecting their job satisfaction and performance (Golden et al., 2008; Spilker & Breaugh, 2021). Despite the potential adverse effects of telework, employees want to telework—they like to have the opportunity to decide where to work (Chen, 2021; Korkeakunnas et al., 2023; Krajčík et al., 2023). Overall, telework can be perceived as having positive or negative associations with performance depending on the work-related circumstances, employees’ characteristics, or the work task’s type and size (Bao et al., 2022).

Previous studies indicate that specific tasks are carried out efficiently in a remote, home-based setting, whereas others are more suited for the traditional office environment (Korkeakunnas et al., 2023; Kowalski & Ślebarska, 2022). According to Golden and Gajendran (2019), tasks requiring focus and problem-solving, such as reading and writing contracts, are more effectively completed at home because of reduced distractions. They also reported that people with jobs requiring minimal collaboration with others perform better when teleworking, whereas for tasks that depend on close collaboration, telework has a neutral effect on performance. Recent research also shows that communication between teleworkers is more task-focused and less prone to distractions (Kowalski & Ślebarska, 2022). Communication devices that are available now have made it quicker and easier to perform tasks such as organizing and attending work meetings online than face-to-face contacts (Kowalski & Ślebarska, 2022). Overall, the nature of the job, for example, the type of work tasks and frequency of teamwork, is relevant when evaluating the impact of teleworking on job performance.

This qualitative study investigates how telework is perceived among occupational groups with different work tasks within the same company. It aims to explore how managers and employees experience telework in relation to well-being, individual performance, and the work environment. Managers, as an occupational group, have other responsibilities and, to some extent, different work tasks than employees do. For example, managers are responsible for the business’s development, finances, and personnel, i.e., leading employees to achieve set goals. This could require closer collaboration with employees to manage work tasks and perform at work. Employees, on the other hand, may have areas of responsibility or work tasks that they need to perform, such as meeting specific targets and goals or office management (i.e., planning, organizing, coordinating, and controlling office activities), with less time needed to interact with coworkers to be able to perform at work and contribute to overall progress. Since the types of work tasks and responsibilities differ between these two groups, deeper knowledge about the similarities and variations in their experiences with telework would lead to a better understanding of how telework affects well-being, individual performance, and the work environment.

Telework can be seen either as a resource or a demand, depending on the work tasks involved. Tasks that require focus and problem-solving tend to be completed more effectively in a telework setting, as they minimize distractions (Golden & Gajendran, 2019). Therefore, for employees and managers engaged in individual tasks, telework provides flexibility in terms of work hours and location, which can help manage job demands and reduce stress, especially by lowering commuting (Golden, 2009). Nonetheless, telework may hinder collaboration in teamwork-dependent tasks and tasks that need constant interaction, making it a challenge or a demand (Kowalski & Ślebarska, 2022). According to the job demands-resources theory, job demands refer to a job’s physical and psychological costs for the individual, whereas job resources help employees reach their work-related goals, reduce job demands, and stimulate personal growth and development (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007; Bakker et al., 2023). The job demands–resources (JD-R) model offers a framework for how the balance of job demands (e.g., workload, work-life boundaries) and resources (e.g., autonomy, flexibility) influences well-being and performance (Peiró et al., 2024). According to (Bakker et al., 2023), JD-R theory can be applied across different contexts and jobs; therefore, it is suitable for discussing the findings of this study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study used a phenomenographic research approach. Phenomenography aims to discover humans’ experiences with different objects and is used by researchers to identify potential variations in the collected data (Marton & Pong, 2005). It is important to consider the interrelationship between the subject (Interviewee) and the object (Telework) (Barnard et al., 1999), including the entire context and perspective, such as the company where the interviewees work, their work assignments, and their job roles. The method can provide valuable insights into how telework is perceived and practiced within the company, as perceptions may vary depending on the job role and type of work performed. Data were collected via semi-structured interviews. Questions were constructed inspired by previous studies and phrased to allow participants to reflect on their experiences (Bowden et al., 1992).

2.2. Participants

This study was conducted within the 6-year Forte program “Flexible Work—Opportunity and Challenge” (Svensson et al., 2022). Contact people from one of the organizations participating in the Forte program were asked to provide a list of names and contact information for managers and employees with telework experience. The list needed to contain managers and employees of different ages and tenures who had the opportunity to telework. One of the authors contacted the participants and sent an invitation for an online interview.

In total, 14 interviewees (i.e., seven employees and seven managers) working in a large industrial company in Sweden were included in the study. Their ages ranged between 27 and 60 years; 29% were women, and 71% were men. They worked in different departments: sales, IT, production, security, project management, design, and HR. Some of them worked globally; they were based in Sweden but had work colleagues, managers, and customers in other countries, which added complexity to their communication and collaboration. The sales, security, and production departments worked and had their work colleagues in Sweden. Most of them had no experience with teleworking before the COVID-19 pandemic. During the pandemic (2020–2022), employees in Sweden who could work from home were recommended to do so for a longer period, resulting in quick changes and new routines (Ludvigsson, 2023). A new teleworking policy was developed in the company after the pandemic in 2022. According to the interviewees, the new policy stipulated that the distribution of working time between the work site and teleworking would be 51/49 percent annually. The highest management level decided the policy, which covers all employees in the company. The new policy was valid during some of the interviews (approximately 40% of the interviews). Before the policy, most employees and managers teleworked approximately 50 percent of the time. Four interviewees had different work patterns: one manager and one employee teleworked over 90% of the time due to global responsibilities, while one manager worked mainly at the office for security reasons and another due to her work tasks at the production department. All managers and employees lived in Sweden and had worked in the company for two to thirty years. Most of the managers who participated in this study were middle managers (see Table 1). The names in the table are fictitious.

Table 1.

Descriptive information about the study participants.

2.3. Data Collection

The interview guide contained 21 open-ended questions, including background information about the interviewees and the company and questions about telework inspired by previous studies in the research field (see Supplementary Material for the interview guide). An example of a question brought up during the interview was, “How does telework affect the work environment?” All the interviewees were encouraged to speak openly about their experiences. Follow-up questions such as “In what way? Could you be more precise?” were used to clarify their answers. Managers and employees were asked to reflect on the same themes and questions, i.e., how they believed that telework affected well-being, individual performance, and the work environment, but the follow-up questions differed depending on the interview. One of the authors completed the interviews. All the interviews were conducted in relaxed and private settings.

The interviews were held between February 2022 and September 2023. The participants received information about the study and the consent form via e-mail and gave their written consent to participate in the study. The interviews were conducted individually and online via the Microsoft Teams® platform (version 1.6.00.4472). They were recorded with the participants’ permission. The interviews lasted between 40 and 60 min. This study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (2019-06220 and 2022-05554-02).

2.4. Analyses

The interviews were transcribed and exported to ATLAS. Ti Win (version 9.1.6.0) (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, 2022). The data analysis, or the path taken to build the results, was conducted in an inductive process based on empirical data, i.e., the content of the interviews (da Rocha-Pinto et al., 2019).

One of the authors analyzed all the transcripts and conducted the first coding of the material. Thereafter, all authors participated in the analysis process to ensure that no relevant information was excluded or that irrelevant information was included and to increase the credibility of the findings. The statements and codes were analyzed and discussed several times before the categories were built. A category represents a group of similar data organized together, allowing for comparison and contrast with other categories (Morse, 2008).

The analysis adopted the following process of phenomenography according to Marton (1994).

- Step 1: Identifying the Phenomenon

The phenomenon under investigation was the experience of telework among employees with different occupations in a large industrial company.

- Step 2: Selection of significant statements

Significant statements from the interviews were selected that reflected different ways of experiencing telework in relation to well-being, individual performance, and the work environment. Thereafter, codes were assigned to the different statements via ATLAS.ti.

- Step 3: Group Statements into Categories

The codes were grouped based on their similarities, forming groups of statements that were then organized into categories. In ATLAS.ti, memos were used to document thoughts, interpretations, and observations during data analysis. They helped build networks of related concepts, facilitating a more structured and coherent analysis, which allowed for a better understanding of relationships and emerging patterns in the interviews.

- Step 4: Analyzing the Categories for Structural Relationships

The final step included analyzing how these categories were related and establishing their structural relationships. The description of the categories highlights the increasing complexity of telework experiences as one moves from the individual level to the organizational level.

The results are presented in the form of an outcome space. It contains the different categories identified in the study, together with descriptions and significant statements. It also shows how the categories are organized (structural relationship).

3. Results

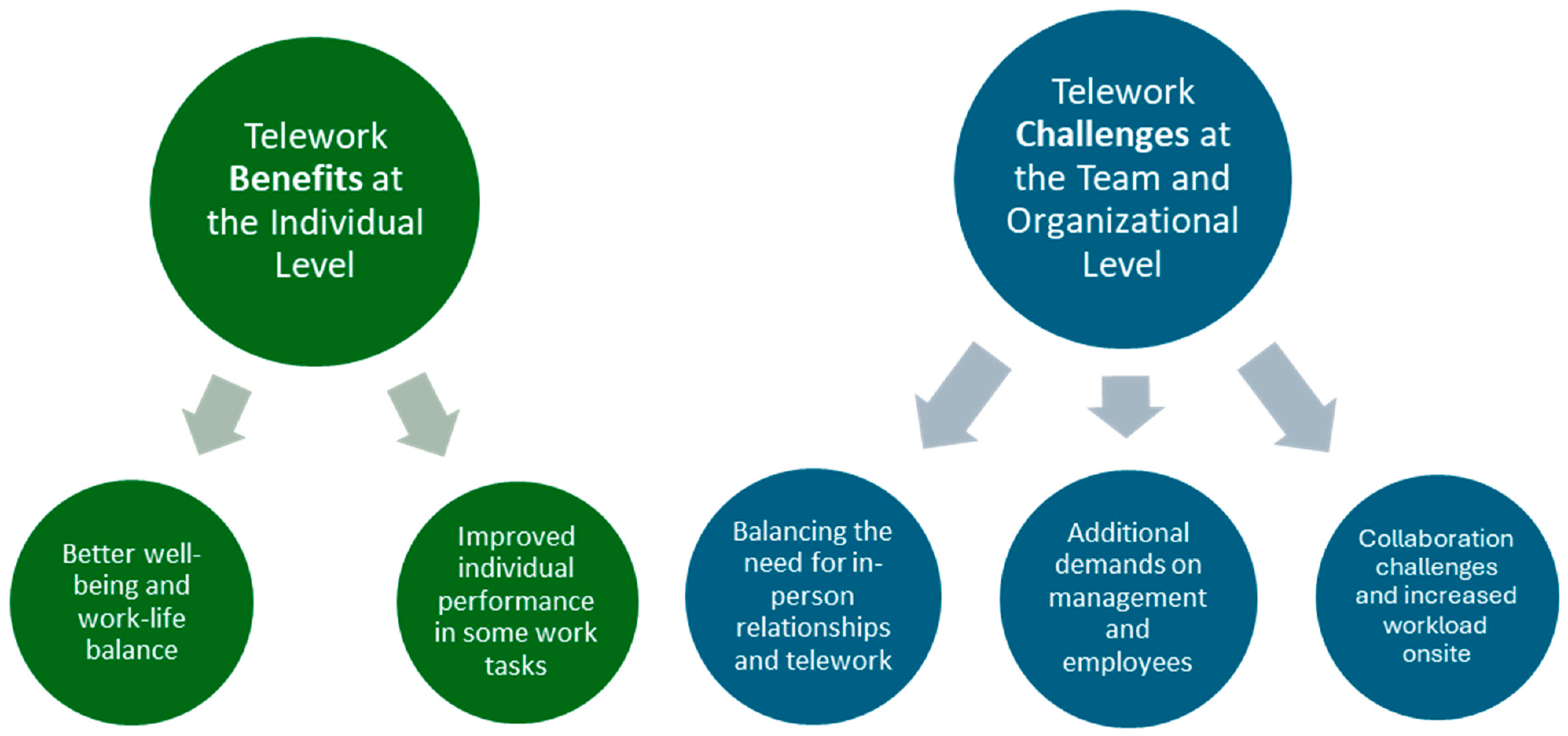

In total, five different categories were created based on the empirical data (Table 2). The categories are ordered hierarchically into three levels: individual level (categories 1 and 2), team level (categories 3 and 4), and organizational level (category 5), showing how telework affects each of these levels in different ways.

Table 2.

Structural relationship, category, description of the category, and associated quotations. Categories 1–2 refer to the individual level, categories 3–4 refer to the work team level, and category 5 refers to the organizational level.

3.1. Individual Level

3.1.1. Telework Promotes Well-Being and Work–Life Balance

Overall, telework enhances well-being by reducing stress and improving work–life balance for both employees and managers. The flexibility that came with telework allowed for a better balance between work and private life while maintaining the same level of professional engagement. Many of the respondents relied on having the opportunity to telework. They had built their lives around it since the COVID-19 pandemic, e.g., living miles away from the work site, dropping off and picking up children from school during the day, and doing other daily chores, as described by one male employee and one male manager (see Table 2, second quotation and third quotation in the table).

Telework was also perceived to reduce the physical strain and stress associated with frequent business travel, thereby enhancing well-being and work–life balance. Employees and managers also reported that telework allowed them to exercise more, was good for motivation, and enhanced their health and overall well-being, as one female employee (see Table 2, fourth quotation) and one male manager said:

I find it positive that this flexibility is available. As an employee, it’s reassuring to know that I have this option, and as a manager, I see its value—for instance, if something urgent comes up at home or if I feel that I’m not in the best shape to go into the office on a particular day—Lars.

3.1.2. Telework Improves Individual Performance in Some Work Tasks

In general, many managers and employees noted that telework increased their effectiveness and performance, particularly in more individual work tasks such as reading, drafting contracts, and preparing reports. It saves time and energy by reducing the need to travel for meetings locally and internationally. Additionally, many highlighted the benefits of a calm and quiet workspace when teleworking because it allowed work to be free from the distractions of coworkers discussing personal matters. Another benefit of telework was the ability to take advantage of high-productivity periods, allowing individuals to work when they felt most focused. This enhanced performance was closely tied to employees’ well-being; when they felt good, their performance improved (see Table 2, sixth quotation by a male employee and eighth quotation by a female employee).

In addition, one manager found it challenging to be physically present in the office and carry out work duties because employees were often seeking onsite managerial support or approached for small talk, particularly if he was not present frequently. He noted that meeting people in person comes with a different type of stress. Frequent engagement with colleagues could be demanding and time-consuming, leading to increased stress levels. In-person discussions could disrupt and extend the workday, making it challenging to complete tasks efficiently. He also reported that he could make more objective decisions because distance reduced the influence of close personal relationships (see Table 2, ninth quotation).

The perceptions of telework varied depending on job tasks and job roles, such as whether the individual was a manager or employee or held a more global job role. Telework was generally considered less effective in positions requiring constant interaction and immediate feedback, such as production or security, than in job roles involving individual tasks or global responsibilities, as one male manager said:

In terms of security, you lose far too much compared to being onsite—Karl.

Telework was found to be beneficial for those in global job roles. It facilitated collaboration between team members and clients across various regions, enhancing the availability and coordination between work colleagues and customers located in different locations and time zones. It provided more opportunities to connect with international clients on short notice, fostering a quicker workflow and saving time without traveling long distances to a meeting, as one male manager and male employee said (see Table 2, 10th and 11th quotation).

3.2. Team Level

3.2.1. Telework Challenges Collaboration in Some Work Tasks and Increases the Workload Onsite

Telework may lead to challenges with collaboration and team cohesion due to decreased face-to-face interactions. This observation was mainly seen in work tasks where frequent, immediate interactions were essential, such as in production departments and security, where telework can hinder effective teamwork. For example, demonstrating and explaining processes directly within the production department enhanced understanding and was conducted more efficiently in person at the workplace, as this made understanding between colleagues easier, as described by a female manager (see Table 2, 12th quotation).

Telework could also increase the workload for colleagues at the work site. For example, onsite employees had to take over some work tasks for teleworkers since people in the office tend to ask questions to physically present colleagues rather than contact colleagues who are teleworking and responsible for those tasks. This issue was observed within the production department, as one male employee described:

If someone is looking for a person who is teleworking, we (at the worksite) usually have to take care of that errand. It usually works out, but it becomes a moment of disturbance—James.

3.2.2. In-Person Relationships Make Telework Easier

According to some employees and managers, being in the office can help colleagues gain insight into each other’s work and facilitate cooperation. Face-to-face meetings helped build relationships, trust, and a strong culture, which eased communication and made telework functional. Most interviewees indicated that telework becomes more challenging when colleagues are unfamiliar with each other, especially newcomers. It is not easy to engage in conversations and seek help from colleagues if you do not know them, making telework more difficult. It can be challenging to reach out for guidance, making learning and adjusting to the job harder and leading to employee turnover. In contrast, being in an office setting with experienced coworkers allows employees to quickly ask questions and obtain the help that they need, making the learning process easier, as one female employee mentioned:

We had several new people who had joined the office, and ultimately, one ended up quitting after about two months because she wasn’t getting the support that she needed. We didn’t have a strong relationship with people (or culture) to know who to reach out to. If you’re sitting next to someone in the office and you can just say, hey, how do I do this, it makes the learning curve a lot less steep. It’s a lot easier to start in the office, and then you get to know the people, and then it’s easier to work with them remotely—Nora.

3.3. Organizational Level

Unclear Expectations of Telework Practices Create Additional Demands on Management and Employees

Although company policy officially supported telework, it was not always fully embraced in practice, as indicated by interviews. Some employees indicated that management’s tracking of office attendance increased due to telework. Some managers preferred that employees be in the office most of the time, valuing in-person interactions for spontaneous conversations and direct work monitoring. This preference may increase employee stress, as they may feel under constant observation, as described by a female employee (see Table 2, 15th quotation).

Some managers in production noted a reduction in their ability to oversee their teams in a teleworking environment. This situation raised concerns among managers regarding their lack of visibility of their team members’ engagement and well-being when they teleworked. According to one manager, increased autonomy can create difficulties for management in maintaining control and fostering team cohesion. Additionally, frequent teleworking can make individuals feel isolated or excluded from their colleagues, diminishing their sense of belonging within the team. It is crucial to actively engage teleworkers by inviting them to participate in discussions and encouraging their involvement in team activities, as one female manager said:

(When teleworking) You lose track of the pulse—how the staff is doing… When a person is teleworking a lot, it can create a sense of being left out or disconnected from others. It’s important to be proactive and engage that person in the group—Amanda.

Telework is positive for the staff—Amanda.

These findings highlight that perceptions of telework are influenced by an individual’s job role within the organization. Employees and managers often view telework through different lenses, with their own responsibilities shaping their perspectives on its benefits and challenges.

There were some notable differences in how employees and managers viewed managerial support for telework. Most managers believed that telework was fully accepted within the company and actively supported it, emphasizing that work location mattered less as long as employees fulfilled their job requirements. Trust and autonomy were crucial for both managers and employees, with trust being identified as a key factor that made telework possible, as pointed out by one male manager (see Table 2, 18th quotation).

3.4. Model/Summary

The findings revealed that telework is neither universally beneficial nor challenging, even though most benefits are found at the individual level, whereas most challenges are primarily found at the group or organizational level (see Figure 1). At the individual level, telework introduces benefits such as better well-being, enhanced work–life balance, and increased individual performance for both employees and managers engaged in individual work tasks or global collaborations. However, at the team and organizational levels, telework may lead to collaboration challenges and increased workloads for onsite workers. It may also create unclear expectations. These issues can place additional demands on both management and employees. Building in-person relationships before telework emerges as a key factor in addressing these challenges. In other words, achieving a balance between in-person relationships and telework remains a challenge when teleworking. In summary, telework effectiveness is influenced by contextual factors such as team dynamics, job roles, the nature of the work, and the organizational culture.

Figure 1.

Benefits and challenges of telework.

4. Discussion

This qualitative study investigated how telework is perceived among occupational groups with different work tasks within the same company. It aimed to explore how managers and employees experience telework in relation to well-being, individual performance, and the work environment. While managers and employees shared many similar experiences with telework, the experiences varied depending on their work tasks, job roles, and the team setting.

Telework provided benefits such as improved well-being, work–life balance, and individual performance for both employees and managers engaged in individual tasks (e.g., reading, drafting contracts, and preparing reports) or global collaborations. One key factor was beginning with an initial period in the office before shifting to telework. This office-based start could help foster team cohesion, and learning provided a deeper understanding of the organizational culture. The findings also showed that face-to-face onsite work could be time-consuming and, therefore, stressful for some but time-saving for others (e.g., easier problem-solving when fewer explanations were needed). Onsite employees and managers, especially in production, faced increased workloads, as employees tended to rely more on colleagues who were physically present in the office.

The preference for office presence could lead to stress among employees. Some managers emphasized that trust was a prerequisite for making telework functional and chose to focus more on performance than physical presence. Nevertheless, challenges remain, particularly in sustaining engagement and team cohesion. Frequent telework may lead to feelings of disconnection among employees, highlighting the need to actively include teleworkers in team activities to maintain cohesion and smooth collaboration, according to the study.

Although the company policy officially supported telework, interviews revealed a gap between policy intentions and actual practices. Telework policies, developed primarily by top management, may not be adaptable to all job roles or work tasks, which can lead to misunderstandings, increased stress, and hindered collaboration across teams. When telework policies are not collaboratively established and integrated across company operations, they may place additional demands on both managers and employees. These findings highlight the need for flexible policies that accommodate diverse tasks and job roles. Additionally, leaders play a key role in managing telework effectively, promoting inclusivity, and addressing biases to ensure that all employees—either teleworking or in the office—are treated equally and included in team activities.

4.1. Experiences: Benefits

The study indicates that telework benefits employees and managers working with individual tasks or in global job roles. It enhances flexibility, reduces commuting, and promotes well-being and work-life balance. Prior research also indicates that employees who benefit from telework reported greater work engagement, well-being, and work–life balance than employees who could not benefit or did not benefit from telework (Miglioretti et al., 2021). Both employees and managers working with individual tasks or in global roles reported improved well-being, with some also experiencing increased motivation and performance due to telework. According to the interviews, telework helped improve the quality of life, providing more time for physical activities and family time (Charalampous et al., 2019; Vacchiano et al., 2024).

Interestingly, many interviewees have structured their lives around telework, with some living over 500 km away from their workplaces. This level of dependency on telework shows that it is not just a temporary benefit but also necessary for some employees’ well-being and work–life balance. To our knowledge, this dependency on telework appears to be less frequently discussed in prior research, likely due to its increased prevalence following the COVID-19 pandemic, when telework became more widespread. However, this dependency on telework should be taken into consideration when planning future teleworking policies.

Our results also showed that telework can benefit from reducing pressure from direct interpersonal interactions. For example, one manager reported reduced stress and improved objectivity in decision-making while teleworking. His main challenge was that the employees were often seeking onsite managerial support or approached for small talk during his onsite days, which ultimately reduced his efficiency. It is possible that his limited office presence increased colleagues’ need for social contact when he was onsite. This may also reflect the organizational culture, suggesting that telework policies are not fully integrated across the entire organization. Nevertheless, it also raises questions about what is expected in terms of the manager’s performance and how it is evaluated. Should the focus be on the quality of outcomes (e.g., solving conflicts and empowering employees), the quantity of work completed (e.g., administrative tasks), or a balance of both?

Among the interviewees, telework was experienced to reduce physical stress from frequent travel. The findings also showed that well-being and a healthy work–life balance are important for employee performance. According to the interviews, when employees felt well, they performed better. Specifically, employees and managers in global job roles, or those with individual tasks, performed more efficiently when teleworking, benefiting from a distraction-free work environment and improved coordination across different time zones. Interestingly, flexible scheduling, which seemed to be tied to telework opportunities, increased physical activity for some individuals and reduced work–family conflicts. While some researchers, such as Ray and Pana-Cryan (2021), express concerns about blurred boundaries between work and personal life, the present study showed that employees and managers in global job roles viewed telework positively, as it allowed for more individual and family time while supporting both well-being and performance, making telework almost necessary in their work.

From an individual perspective, telework offers autonomy, reduced commuting time, and improved work–life balance, enhancing well-being and individual performance. However, its effectiveness depended on work tasks, job roles, and team settings, including the organizational or situational context. At the team level, telework was beneficial for globally distributed teams. Telework increased their efficiency, particularly in cross-border collaboration roles.

At the organizational level, some interviewees also noted a reduction in business travel, saving time and money for organizations, which in turn may increase overall organizational performance. Therefore, telework can be beneficial not only for individuals but also for organizations. When tasks are well suited for telework, employees are familiar with telework practices, and management provides support—telework can enhance performance and reduce costs across the organization.

4.2. Experiences: Challenges

The study revealed that work tasks requiring close collaboration benefit more from in-person work than from telework, which aligns with Behrens and Kret’s (2019) findings. Similarly, Van der Lippe and Lippényi (2020) reported that increased telework can reduce team performance. According to the interviews, the absence of regular physical interactions can hinder team cohesion, complicate learning, and potentially lead to higher employee turnover rates, which could negatively affect team performance, team dynamics, and overall organizational performance. According to our study, building in-person relationships before adopting telework could facilitate faster learning and cohesion within the team and culture, which might be a solution for handling these challenges. If new personnel join the company workforce regularly, this may require that all personnel regularly spend time at the office, suggesting that a hybrid work model would be beneficial (Silva-C et al., 2019).

Telework may also complicate certain managerial duties, particularly those involving attentive listening and addressing sensitive issues. In this study, some managers reported concerns about reduced visibility in team engagement and well-being (Korkeakunnas et al., 2023; Vitak & Zimmer, 2023). In addition, some employees felt that telework has led to increased monitoring in the workplace, which has led to heightened stress. A recent study showed that increased monitoring by supervisors may lead to negative perceptions among employees, potentially affecting their views on supervisory effectiveness and support, with employees tending to rate their supervisors less favorably (Peiró et al., 2024).

Our findings indicate that telework policies may fail if the company culture, specific job roles, or work tasks are not aligned with telework and if managers lack the skills to lead teleworking teams effectively. This can negatively affect both employee well-being and organizational performance (Urien, 2023). The study suggests that when collaboration is required to achieve results, telework should be an option only if it supports these outcomes. Certain tasks require people to work together in person, and coming into the office helps maintain productivity and team cohesion. Henke et al. (2022) concluded that managers and employees need a shared understanding of what is expected of telework to minimize fears and concerns about the unfair treatment of employees.

4.3. Job Demands–Resources (JD-R Theory)

4.3.1. Telework as a Resource in Independent Work Tasks and Global Collaboration

According to this study, telework serves as a job resource for employees engaged in independent work tasks. It allows concentrated work free from office distractions, thereby enhancing productivity in tasks such as writing, reading, drafting, data analysis, and research. Additionally, telework allows employees to schedule their work tasks during their most productive hours, contributing to improved performance outcomes and a better work–life balance. It is possible that telework can increase motivation by helping employees and managers with heavy workloads to better balance job demands and resources (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017; Schaufeli & Taris, 2014).

According to the interviews, telework can also be an important resource for work tasks that require global coordination or remote collaboration across different time zones. In these cases, our study suggests that telework may reduce the stress of business travel, increase physical activity, enhance work–life balance, and help maintain energy and focus. Above all, it makes it easier for employees to align their schedules with those of international colleagues.

4.3.2. Telework as a Demand in Interdependent Work Tasks, Relationship Building, and Support Tasks

The study shows that telework can make work more demanding for employees who rely on collaboration and team interdependence. In particular, tasks requiring face-to-face interaction, spontaneous problem-solving, or shared decision-making require more effort when teleworking. In essence, the benefits of telework in terms of fewer disruptions may come at the cost of less communication and reduced information sharing. The lack of immediate in-person feedback from colleagues can slow down task completion and lower efficiency, particularly in a fast-moving environment.

When physical presence is needed to coordinate tasks, employees may experience more stress when part of the team is teleworking. For example, in production, where tasks require onsite monitoring, telework can place an additional burden on employees who remain onsite. This increased workload may lead to a disconnection between teleworkers and onsite workers, creating friction that negatively impacts performance.

Telework can also pose challenges for relationship building, on-the-job training, and mentorship, which are crucial for new employees. These workers often rely on informal networks for guidance, but telework can lead to isolation and difficulty accessing support, causing disengagement and stress. Isolation stands out as a negative side of telework, “posing a potential risk to employees’ psychological well-being” (Miglioretti et al., 2021). Over time, limited personal contact can harm relationships, job satisfaction, and motivation, potentially leading to learning difficulties and employee turnover.

4.4. Practical Implications for Management

Telework is associated with both benefits and challenges for employers. Through a well-thought-out use of telework, employers can leverage the benefits while managing the negative consequences of the identified challenges.

Based on the findings in this study, employers are recommended to have an office-based period for new employees before transitioning to a hybrid work model. It promotes stronger team cohesion, faster learning, and a deeper understanding of organizational culture. It may even help reduce turnover.

Telework policies need to be flexible and accommodate contextual factors such as team setting, job role, type of work, and organizational culture. Individual work tasks or global collaboration are more efficiently conducted while teleworking. When collaboration is required to achieve results, coming into the office helps maintain productivity. Therefore, telework should be an option only if it supports the requested outcomes.

Telework increases demands on both managers and employees. If managers lack the skills to lead teleworking teams effectively, the identified challenges may not be managed, and benefits may not be utilized. It requires employees to lead themselves and take responsibility for organizing their work in a way that contributes to positive outcomes both for the organization and for themselves as individuals.

4.5. Limitations

This qualitative study aimed to gain a deeper understanding of how telework is perceived among occupational groups with different work tasks within the same company. More specifically, how do managers and employees experience telework in relation to well-being, individual performance, and the work environment?

On the one hand, participants’ unique experiences make it difficult to generalize and replicate the results (Gheondea-Eladi, 2014). On the other hand, the flexibility of the interviews encouraged participants to share more about their experiences, thereby enhancing the richness of the qualitative data (Alamri, 2019).

The sample for this study included male and female managers and employees from a Swedish industrial company. The findings may be applicable to other industrial organizations in Sweden and perhaps in other Nordic countries, but they should be applied with caution. Additionally, the sample consisted of fourteen interviews, which, although relatively small, appeared to have reached saturation (Morse, 1995). Most of the managers were middle managers, and a manager’s position in the organization could influence their perceptions of telework.

The interviews were carried out online, potentially limiting our ability to interpret body language and facial expressions (Graneheim & Lundman, 2004). Nonetheless, the interviewees were comfortable with the software. To increase the credibility of the findings, all the authors participated in the coding process, reformulating and revising the codes before final selection.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the findings showed that telework is not universally beneficial or challenging; its effectiveness depends on contextual factors such as team setting, job role, type of work, and organizational culture. While telework could benefit individual tasks or global collaboration, it could pose challenges in interdependent work tasks, relationship building, and support tasks. This study emphasizes the importance of both employees’ and managers’ understanding of how their telework might affect their team members, team dynamics, collaboration, and overall organizational performance. Even if telework policies are in place, they might be insufficient if the organizational culture or specific work tasks are not well suited for telework.

By showing variations in telework experiences across different occupational groups, this research highlights the need for tailored strategies to enhance the advantages of telework while reducing its challenges. It contributes to existing research by providing nuanced insights into the relationship between telework and occupational groups within an industrial context while also offering practical guidance for telework in this field.

Future research could focus on understanding how telework and work characteristics affect individual performance and consider their impact on the performance of other team members, for example, in quantitative studies of homogeneous populations who telework regularly, to identify patterns that are associated with high productivity. Additionally, further studies might investigate how virtual teams establish and maintain organizational culture without face-to-face interactions.

Supplementary Materials

The Supplementary Material can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/admsci15020056/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.K., M.L.-K., M.H. and K.R.; methodology, T.K., M.L.-K., M.H. and K.R.; software, T.K.; validation, T.K., M.L.-K., M.H. and K.R.; formal analysis, T.K.; investigation, T.K.; resources, T.K.; data curation, T.K. and M.H.; writing—original draft preparation, T.K.; writing—review and editing, T.K., M.L.-K., M.H. and K.R.; visualization, T.K., M.L.-K., M.H. and K.R.; supervision, M.L.-K., M.H. and K.R.; project administration, T.K. and M.H.; funding acquisition, M.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working life and Welfare—Forte, grant number 2019-01257.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (protocol code: 2019-06220/2022-05554-02; date of approval: 21 October 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Supporting data are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the informants for their contributions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funding body had no influence on the design, process, or conduct of this study.

References

- Adamovic, M. (2022). How does employee cultural background influence the effects of telework on job stress? The roles of power distance, individualism, and beliefs about telework. International Journal of Information Management, 62, 102437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamri, W. A. (2019). Effectiveness of qualitative research methods: Interviews and diaries. International Journal of English and Cultural Studies, 2, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, F., Pereira, L. F., Dias, Á. L., & da Silva, R. V. (2023). Flexible labour policies as competitive advantage. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 24(4), 563–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH. (2022, April 22). ATLAS.ti 22 Windows. Available online: https://atlasti.com (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Sanz-Vergel, A. (2023). Job demands–resources theory: Ten years later. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 10(1), 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, L., Li, T., Xia, X., Zhu, K., Li, H., & Yang, X. (2022). How does working from home affect developer productivity?—A case study of Baidu during the COVID-19 pandemic. Science China Information Sciences, 65(4), 142102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, A., McCosker, H., & Gerber, R. (1999). Phenomenography: A qualitative research approach for exploring understanding in health care. Qualitative Health Research, 9(2), 212–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrero, J. M., Bloom, N., & Davis, S. J. (2023). The evolution of working from home (No. 23-19). The Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR).

- Beckel, J. L. O., & Fisher, G. G. (2022). Telework and worker health and well-being: A review and recommendations for research and practice. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), 3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behrens, F., & Kret, M. E. (2019). The interplay between face-to-face contact and feedback on cooperation during real-life interactions. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 43(4), 513–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, J., Dall’Alba, G., Martin, E., Laurillard, D., Marton, F., Masters, G., Ramsden, P., Stephanou, A., & Walsh, E. (1992). Displacement, velocity, and frames of reference: Phenomenographic studies of students’ understanding and some implications for teaching and assessment. American Journal of Physics, 60(3), 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalampous, M., Grant, C. A., Tramontano, C., & Michailidis, E. (2019). Systematically reviewing remote e-workers’ well-being at work: A multidimensional approach. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 28(1), 51–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z. (2021). Influence of working from home during the COVID-19 crisis and HR practitioner response. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 710517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, A. M. Y., Chan, T. W. C., & So, M. K. P. (2022). Learning from work-from-home issues during the COVID-19 pandemic: Balance speaks louder than words. PLoS ONE, 17(1), e0261969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Rocha-Pinto, S. R., Jardim, L. S., De Souza Broman, S. L., Guimaraes, M. I. P., & Trevia, C. F. (2019). Phenomenography’s contribution to organizational studies based on a practice perspective. RAUSP Management Journal, 54(4), 384–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. (2023). Employed persons working from home as a percentage of the total employment, by sex, age and professional status (%). Eurostat. [Google Scholar]

- Gheondea-Eladi, A. (2014). Is qualitative research generalizable? Journal of Community Positive Practices, 3, 114–124. [Google Scholar]

- Golden, T. D. (2009). Applying technology to work: Toward a better understanding of telework. Organisation Management Journal, 6(4), 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, T. D., & Gajendran, R. S. (2019). Unpacking the role of a telecommuter’s job in their performance: Examining job complexity, problem solving, interdependence, and social support. Journal of Business and Psychology, 34(1), 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, T. D., Veiga, J. F., & Dino, R. N. (2008). The impact of professional isolation on teleworker job performance and turnover intentions: Does time spent teleworking, interacting face-to-face, or having access to communication-enhancing technology matter? Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(6), 1412–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graneheim, U. H., & Lundman, B. (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24(2), 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henke, J. B., Jones, S. K., & O’Neill, T. A. (2022). Skills and abilities to thrive in remote work: What have we learned. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 893895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, S., Engelsted, L., Lei, X., & Lockwood, K. (2018). Unpackaging manager mistrust in allowing telework: Comparing and integrating theoretical perspectives. Journal of Business and Psychology, 33(3), 365–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkeakunnas, T., Heiden, M., Lohela-Karlsson, M., & Rambaree, K. (2023). Managers’ perceptions of telework in relation to work environment and performance. Sustainability, 15(7), 5845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, G., & Ślebarska, K. (2022). Remote working and work effectiveness: A leader perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 15326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajčík, M., Schmidt, D. A., & Baráth, M. (2023). Hybrid work model: An approach to work–life flexibility in a changing environment. Administrative Sciences, 13(6), 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludvigsson, J. F. (2023). How Sweden approached the COVID-19 pandemic: Summary and commentary on the National Commission Inquiry. Acta Paediatrica, 112(1), 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lunde, L.-K., Fløvik, L., Christensen, J. O., Johannessen, H. A., Finne, L. B., Jørgensen, I. L., Mohr, B., & Vleeshouwers, J. (2022). The relationship between telework from home and employee health: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marton, F. (1994). Phenomenography. In The international encyclopedia of education (2nd ed., Vol. 8). Pergamon. [Google Scholar]

- Marton, F., & Pong, W. Y. (2005). On the unit of description in phenomenography. Higher Education Research & Development, 24(4), 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miglioretti, M., Gragnano, A., Margheritti, S., & Picco, E. (2021). Not all telework is valuable. Revista de Psicología Del Trabajo y de Las Organizaciones, 37(1), 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, J. M. (1995). The significance of saturation. Qualitative Health Research, 5(2), 147–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, J. M. (2008). Confusing categories and themes. Qualitative Health Research, 18(6), 727–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutiganda, J. C., Wiitavaara, B., Heiden, M., Svensson, S., Fagerström, A., Bergström, G., & Aboagye, E. (2022). A systematic review of the research on telework and organizational economic performance indicators. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1035310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiró, J. M., Bravo-Duarte, F., González-Anta, B., & Todolí-Signes, A. (2024). Supervisory performance in telework: The role of job demands, resources, and satisfaction with telework. Frontiers in Organizational Psychology, 2, 1430812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Predotova, K., & Vargas Llave, O. (2021). Workers want to telework but long working hours, isolation and inadequate equipment must be tackled. Eurofound. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, T. K., & Pana-Cryan, R. (2021). Work flexibility and work-related well-being. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiter-Palmon, R., Kramer, W., Allen, J. A., Murugavel, V. R., & Leone, S. A. (2021). Creativity in virtual teams: A review and agenda for future research. Creativity Theories–Research–Applications, 8(1), 165–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., & Taris, T. W. (2014). A critical review of the job demands-resources model: Implications for improving work and health. In Bridging occupational, organizational and public health (pp. 43–68). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-C, A., Montoya R, I. A., & Valencia A, J. A. (2019). The attitude of managers toward telework, why is it so difficult to adopt it in organizations? Technology in Society, 59, 101133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spilker, M. A., & Breaugh, J. A. (2021). Potential ways to predict and manage telecommuters’ feelings of professional isolation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 131, 103646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistikmyndigheten [Statitics Sweden]. (2023). Sex av tio jobbar inte alls hemifrån. [Six out of ten do not work from home at all]. Sveriges Företagshälsor [Swedish Occupational Health]. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson, S., Hallman, D. M., Mathiassen, S., Heiden, M., Fagerström, A., Mutiganda, J. C., & Bergström, G. (2022). Flexible work: Opportunity and challenge (FLOC) for individual, social and economic sustainability. Protocol for a prospective cohort study of non-standard employment and flexible work arrangements in Sweden. BMJ Open, 12(7), e057409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urien, B. (2023). Teleworkability, preferences for telework, and well-being: A systematic review. Sustainability, 15(13), 10631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacchiano, M., Fernandez, G., & Schmutz, R. (2024). What’s going on with teleworking? A scoping review of its effects on well-being. PLoS ONE, 19(8), e0305567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Lippe, T., & Lippényi, Z. (2020). Co-workers working from home and individual and team performance. New Technology, Work and Employment, 35(1), 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vayre, É., Morin-Messabel, C., Cros, F., Maillot, A.-S., & Odin, N. (2022). Benefits and risks of teleworking from home: The teleworkers’ point of view. Information, 13(11), 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitak, J., & Zimmer, M. (2023). Surveillance and the future of work: Exploring employees’ attitudes toward monitoring in a post-COVID workplace. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 28(4), zmad007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).