1. Introduction

Effective human resources management is fundamental to the success and sustainability of any organization, as it includes all decisions that directly affect employees (

Kurniadi et al. 2018). Human resource management needs to optimize using all available resources, developing quality human resources that possess skills and are highly competitive in global competition (

Edison et al. 2016). Within this context, retaining talent becomes a crucial strategic challenge, especially in a dynamic scenario where employee turnover is a phenomenon with a multifaceted impact. Organizations are less and less able to guarantee the security of their employees, which often culminates in their voluntary departure in search of stability and security (

Benson 2006). Employee turnover, as well as being an inherent reality of the contemporary corporate environment, triggers a series of profound implications beyond simply replacing human resources. Therefore, organizations must adapt their strategies to retain their best employees and, as a result, maintain the skills essential to their strategic plans (

Afiouni 2007).

Organizational culture should be considered one of the essential aspects of an organization’s sustainability, as it can optimize its functioning and ensure that the proposed objectives are achieved (

Indiyati et al. 2021). When an organization has a positive organizational culture that leads it to invest in its employees (

Indiyati et al. 2021), they reciprocate with positive attitudes and behaviors, such as affective commitment (

Pathan 2022), and their turnover intentions decrease, i.e., they stay with the organization (

Saripudin et al. 2023). This relationship can be interpreted based on the premise of social exchange, a theory developed by

Blau (

1964). According to this theory, through mutual and contingent exchanges, the interactions between employees and organizations allow us to understand the patterns formed to initiate, maintain or terminate a relationship.

This leads us to pose the following research question:

Are competence development and affective commitment the mechanisms that explain the relationship between organizational culture and exit intentions?

This study has two objectives: the first is to test the effect of organizational culture on turnover intentions, and the second is to test whether organizational competence development practices and affective commitment are the mechanisms explaining the relationship between organizational culture and turnover intentions.

The objectives were established to answer this research question, and seven hypotheses were formulated and tested using a quantitative methodology. The first six hypotheses were tested using multiple linear regressions in the SPSS Statistics 29 program. Hypothesis seven, which assumed a serial mediating effect, was tested using the Macro Process developed by

Hayes (

2013). The results showed that among the four dimensions of organizational culture, only support culture and goal culture significantly affect turnover intentions, and that organizational practices of competency development and affective commitment have a serial mediating effect on these relationships. These results indicate that organizations should be concerned with implementing a type of organizational culture that fosters the development of competencies and the affective commitment of employees to reduce their turnover intentions.

3. Method

3.1. Data Collection Procedure

This study involved 369 individuals, all of whom worked in organizations based in Portugal, belonging to diversified sectors. The sampling process was non-probabilistic, convenience and intentional snowball sampling (

Trochim 2000). This is a cross-sectional study, as the data were collected at a single point in time.

The questionnaire was created online on the Google Forms platform, and its link was sent via email and LinkedIn. As soon as they accessed the questionnaire link, participants were given access to the informed consent form, which guaranteed the confidentiality of their answers. After reading the informed consent, the participants had to answer a question about whether they agreed to take part in the study. If they answered no, they were taken to the end of the questionnaire; if they answered yes, they were taken to the next section. Of the 374 participants, 369 said yes and participated in the study.

To characterize the sample, the questionnaire included the following socio-demographic questions: age, gender, length of service in the organization, educational qualifications, marital status, sector of activity and type of contract. In addition to these questions, the participants answered three scales: organizational culture, organizational skills development practices, affective commitment and turnover intentions.

3.2. Participants

The study sample consisted of 369 participants aged between 19 and 70 (M = 38.39; SD = 11.80), 202 (54.7%) female and 167 (54.3%) males. In terms of educational qualifications, 82 (22.2%) had a 12th-grade degree or less, 174 (47.2%) had a bachelor’s degree and 113 (30.6%) had a master’s degree or higher. As for marital status, 152 (42%) are single, 183 (49.6%) are married or in a civil partnership and 31 (8.4%) are divorced. Regarding the length of service in the organization, 65 (17.6%) had been there for less than a year, 61 (16.5%) for between one and two years, 89 (24.1%) for between two and five years, 57 (15.4%) for between five and ten years, 45 (12.2%) for between ten and 20 years and 52 (14.1%) for more than 20 years. About the type of contract, 49 (13.3%) have an uncertain term contract, 45 (12.2%) have a fixed-term contract, 247 (66.9%) have an open-ended contract and 28 (7.6%) have another type of contract.

3.3. Data Analysis Procedure

Once data collection was complete, it was imported into SPSS Statistics software 29 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The first step was to test the metric qualities of the instruments used in this study. AMOS Graphics software for Windows 29(IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used to test the validity of the instruments. The procedure followed a ‘model generation’ logic (

Jöreskog and Sörbom 1993). Six fit indices were combined, as recommended by

Hu and Bentler (

1999). The fit indices calculated were as follows: chi-squared ratio/degrees of freedom (χ

2/gl); Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI); Goodness-of-fit Index (GFI); Comparative Fit Index (CFI); Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA); Root Mean Square Residual (RMSR). The chi-square/degrees-of-freedom ratio (χ

2/gl) must be less than 5. The CFI, GFI and TLI values must equal or exceed 0.90. As for the RMSEA, for it to be considered a good fit, its value must be less than 0.08 (

McCallum et al. 1996). The lower the RMSR, the better the fit (

Hu and Bentler 1999). With the data obtained from the confirmatory factor analysis, the construct reliability was calculated for each of the dimensions of the scales and the respective convergent validity (by calculating the AVE value). The construct reliability values should be greater than 0.70, and the AVE value should be equal to or greater than 0.50 (

Fornell and Larcker 1981). However, according to

Hair et al. (

2011), if the reliability is higher than 0.70, AVE values equal to or higher than 0.40 are acceptable. The internal consistency of each of the dimensions of the scales was also tested by calculating Cronbach’s alpha, whose value should be equal to or greater than 0.70 in organizational studies (

Bryman and Cramer 2003).

The items’ sensitivity was also tested by calculating the measures of central tendency and shape. The items should have responses at all points, not have asymmetry at one of the extremes and their absolute values of asymmetry and kurtosis should be below 2 and 7, respectively (

Finney and DiStefano 2013).

Descriptive statistics were then carried out on the variables under study, using Student’s

t-tests for independent samples. The association between the variables under study was tested using Pearson’s correlations. Hypotheses 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 were tested using simple and multiple linear regressions. Hypothesis 7, which assumes a serial mediating effect, was tested using Macro Process 4.2, developed by

Hayes (

2013).

3.4. Instruments

To measure organizational culture, we used the FOCUS instrument (first organizational culture unified search), validated and adapted for the Portuguese population (

Neves 2000), consisting of 35 items with a 6-point Likert-type response, with a variable score (

Table A1). Items 1 and 2 are categorized from 1 ‘None’ to 6 ‘All’. Items 3 to 15 are categorized from 1 ‘Never’ to 6 ‘Always’. Items 16 to 35 are categorized from 1 ‘Not at all’ to 6 ‘Very much’. This scale is made up of four dimensions that correspond to the four types of culture in the contrasting values model: innovation culture (items 2, 5, 6, 7, 9, 13, 14, 15, 16 and 33); support culture (items 1, 17, 20, 24, 25, 27, 28, 29, 31, 32 and 34); goals culture (items 3, 4, 8, 10, 11 and 12); rules culture (items 18, 19, 21, 22, 23, 26, 30 and 35). The confirmatory factor analysis showed that the fit indices were adequate or very close to adequate (χ

2/df = 2.01; GFI = 0.87; CFI = 0.94; TLI = 0.93; RMSEA = 0.052; SRMR = 0.088). It should be noted that item 30 had to be removed as it had a low factor weight. The composite reliability values vary between 0.87 (goal culture) and 0.94 (support culture). Convergent validity ranged from 0.48 (culture of innovation) to 0.58 (culture of support). Although the innovation culture has an AVE value of less than 0.50, as its Cronbach’s alpha value is higher than 0.70, it can be considered acceptable convergent validity. The internal consistency shows Cronbach’s alpha values between 0.87 (culture of goals and culture of rules) and 0.94 (culture of support).

The instrument developed by

De Vos et al. (

2011) and adapted for the Portuguese population by

Moreira and Cesário (

2022) was used to measure organizational skills development practices. It consists of 12 items spread across three dimensions: training (items 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 8), individualized support (items 7, 11 and 12) and functional rotation (items 9 and 10) (

Table A2). These items are classified on a 5-point Likert rating scale (from 1 ‘Never’ to 5 ‘Always’). When the CFA was carried out, all the adjustment indices were found to be adequate (χ

2/df = 2.58; GFI = 0.96; CFI = 0.95; TLI = 0.92; RMSEA = 0.066; SRMR = 0.077). Composite reliability ranges from 0.73 (individualized support) to 0.80 (training). Convergent validity varies between 0.40 (training) and 0.58 (functional rotation). The training and individualized support dimensions have AVE values below 0.50, but as their Cronbach’s alpha value is above 0.70, they can be considered acceptable convergent validity. As for internal consistency, Cronbach’s alpha values vary between 0.71 (individualized support) and 0.79 (training).

Turnover intentions were measured using the instrument developed by

Bozeman and Perrewé (

2001), translated and adapted for the Portuguese population by

Bártolo-Ribeiro (

2018). The instrument consists of 6 items classified on a 5-point rating scale (from 1 ‘Strongly Disagree’ to 5 ‘Strongly Agree’) (

Table A3). The confirmatory factor analysis showed that the fit indices were adequate (χ

2/df = 3.03; GFI = 0.99; CFI = 0.99; TLI = 0.98; RMSEA = 0.077; SRMR = 0.037). This instrument has a composite reliability of 0.92 and a convergent validity of 0.66. In terms of internal consistency, the Cronbach’s alpha value is 0.93.

To measure affective commitment, we used the affective commitment dimension of the instrument developed by

Meyer and Allen (

1997). This instrument consists of 6 items classified on a 7-point Likert rating scale (from 1 ‘Strongly Disagree’ to 5 ‘Strongly Agree’) (

Table A4). The confirmatory factor analysis showed that the fit indices were adequate (χ

2/df = 2.65; GFI = 0.99; CFI = 0.99; TLI = 0.98; RMSEA = 0.069; SRMR = 0.027). It has a composite reliability of 0.91 and a convergent validity of 0.63. As for internal consistency, the Cronbach’s alpha value is 0.92.

As for the sensitivity of the items, only item 5 of the exit intentions scale has a median close to the lower extremum. All the items have responses at all points, and their absolute asymmetry and kurtosis values are below 2 and 7, respectively.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to test the effect of organizational culture on turnover intentions and whether this relationship was mediated by organizational practices of development competencies and affective commitment.

Hypothesis 1 was partially proven, as only supportive and goal cultures negatively and significantly affected turnover intentions. These results go partly against what was expected that all the dimensions of organizational culture would have a negative and significant effect on turnover intentions, as in the view of

Said et al. (

2020), organizational culture has a negative and significant effect on turnover intentions. However, in a study by

Salvador et al. (

2022), the results were identical to those of this study since these authors only confirmed the negative and significant effect of supportive culture and goal culture on turnover intentions.

Hypothesis 2 was partially supported. The culture of innovation only has a positive and significant effect on training. It is natural for an organization with an innovation culture to boost the training of its employees, as they are required to have a high level of specialization (

Quinn and Cameron 1983). A culture of goals has a positive and significant effect on training, functional rotation and individualized support, which is natural given that this culture is characterized by a focus on goals and directed towards achieving the organization’s objectives (

Pinho et al. 2013). A supportive culture positively and significantly affects functional rotation and individualized support. These results are in line with

Niguse’s (

2019) recommendations, that to promote a supportive culture, an organization must offer strategies with open and transparent communication channels, offer mentoring and coaching programs and promote collaboration and teamwork, suggestions that fit in with job rotation and individualized support.

Hypothesis 3 was partially supported since only a supportive culture and a culture of objectives positively and significantly affect affective commitment. These results align with the literature because when an organization has a supportive culture, employees feel supported, valued and respected by the organization where they work, showing greater job satisfaction and feeling more committed to it (

Mashile et al. 2019). According to

Haffar et al. (

2023), a culture that promotes trust, transparency, collaboration and mutual support creates a working environment where employees feel valued, have a sense of belonging and are motivated to contribute to the change initiative for the organization’s success. It should be emphasized that the culture of support has the strongest effect on affective commitment. This result is in line with the findings of

Sarhan et al. (

2019), who found that a supportive culture is most strongly associated with affective commitment. Concerning a culture of objectives, as the focus of this type of culture is the organization’s goals and the achievement of its objectives, if the communication of these is effective, employees feel aligned with it, more motivated and more committed (

Pinho et al. 2013).

As expected, hypothesis 4 was supported. Organizational practices of development competencies (training, functional rotation and individualized support) negatively and significantly affect turnover intentions. These results are in line with the literature. From the perspective of

Syed et al. (

2023), training has a negative and significant effect on turnover intentions. According to

Indra et al. (

2023), the organization’s and the manager’s support reduces turnover intentions. In the study by

Moreira et al. (

2024), which used the same instrument as this study to measure organizational skills development practices, the authors concluded that training, job rotation and individualized support reduce turnover intentions. Moreover, in line with this study,

Moreira et al. (

2024) also concluded that the dimension with the weakest effect on turnover intentions is functional rotation.

As expected, hypothesis 5 was supported: organizational practices of development competencies (training, functional rotation and individualized support) positively and significantly affect affective commitment. These results align with the literature, which states that organizational practices of development competencies boost affective commitment (

Moreira et al. 2024). This relationship can be interpreted in the light of the social exchange theory (

Blau 1964), since when the organization invests in its employees, they reciprocate this investment by developing a greater affective commitment to the organization.

Sixthly, as expected, affective commitment significantly negatively affected turnover intentions. These results are also in line with the literature.

Indra et al. (

2023) state that affective commitment reduces turnover intentions. It should be noted that of all the variables used in this study, affective commitment proved to be the greatest reducer of turnover intentions.

Meyer and Allen (

1991) pointed out that the great interest in studying affective commitment may be related to the fact that it is the greatest reducer of turnover intentions.

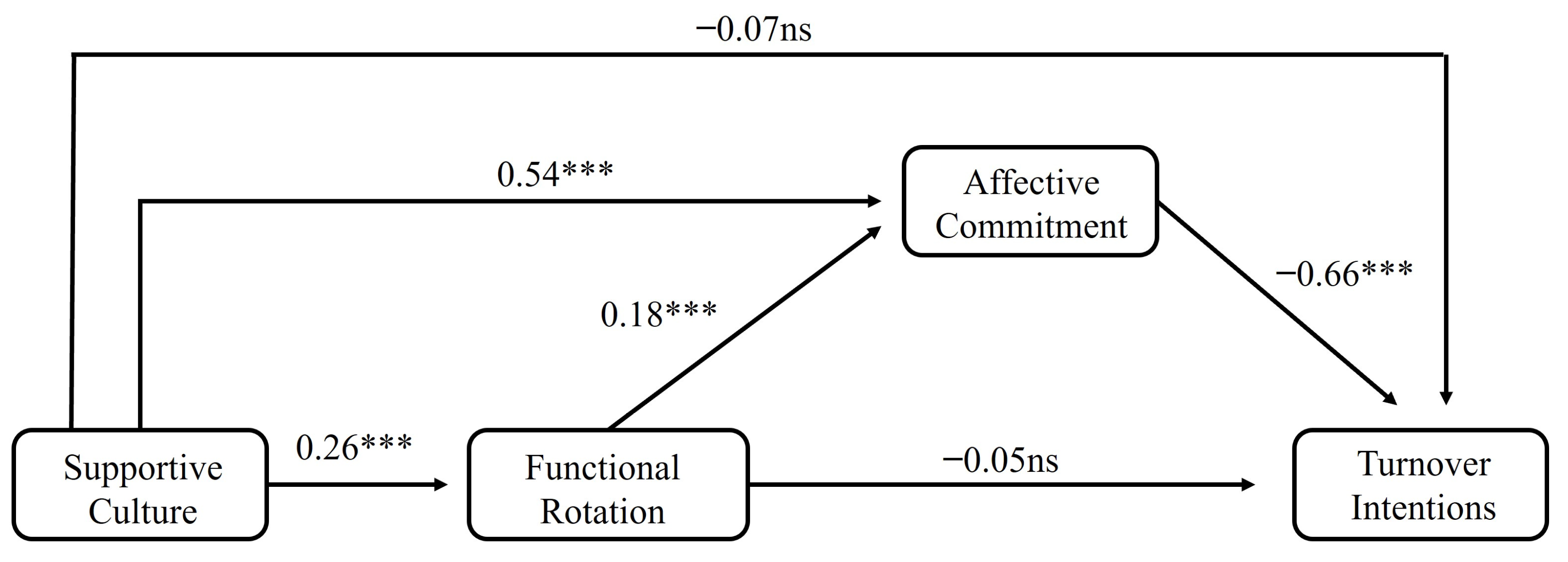

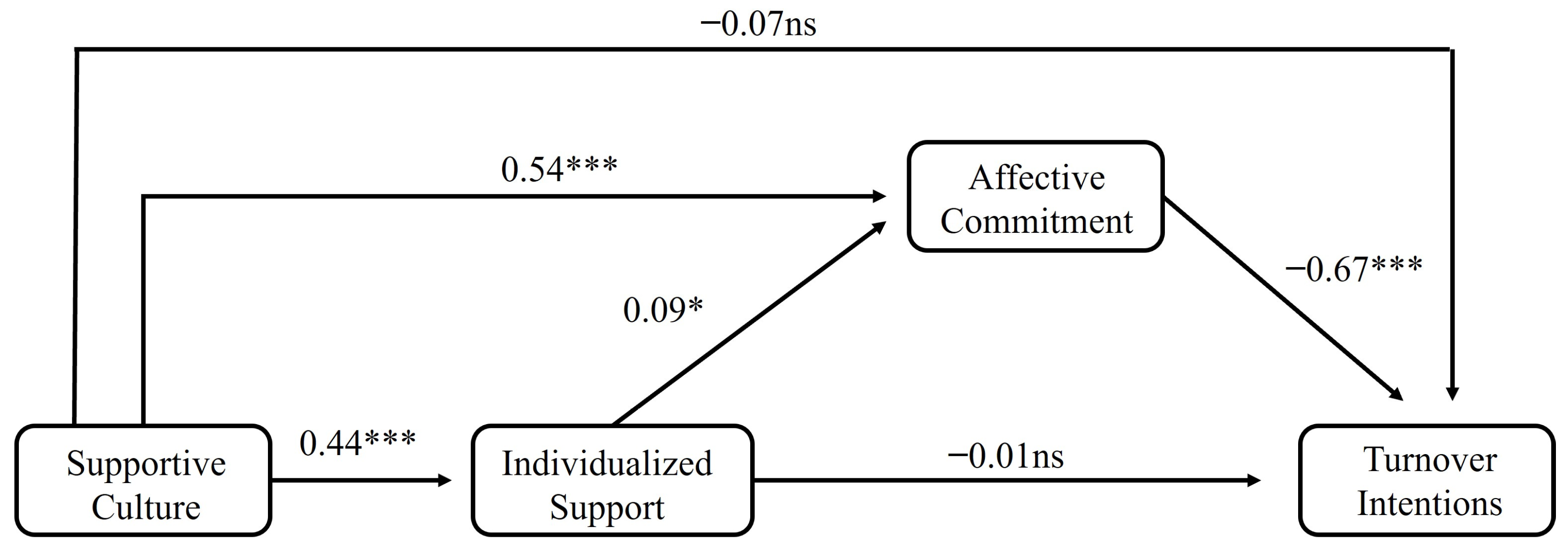

Finally, some serial mediating effects were confirmed. The serial mediating effect of functional rotation and affective commitment on the relationship between supportive culture and turnover intentions was proven, as was the serial mediating effect of individualized support and affective commitment on the relationship between supportive culture and turnover intentions. When an organization has a supportive culture, it boosts turnover and individualized support (

Niguse 2019), which in turn boosts affective commitment (

Moreira et al. 2024) and reduces turnover intentions (

Benson 2006;

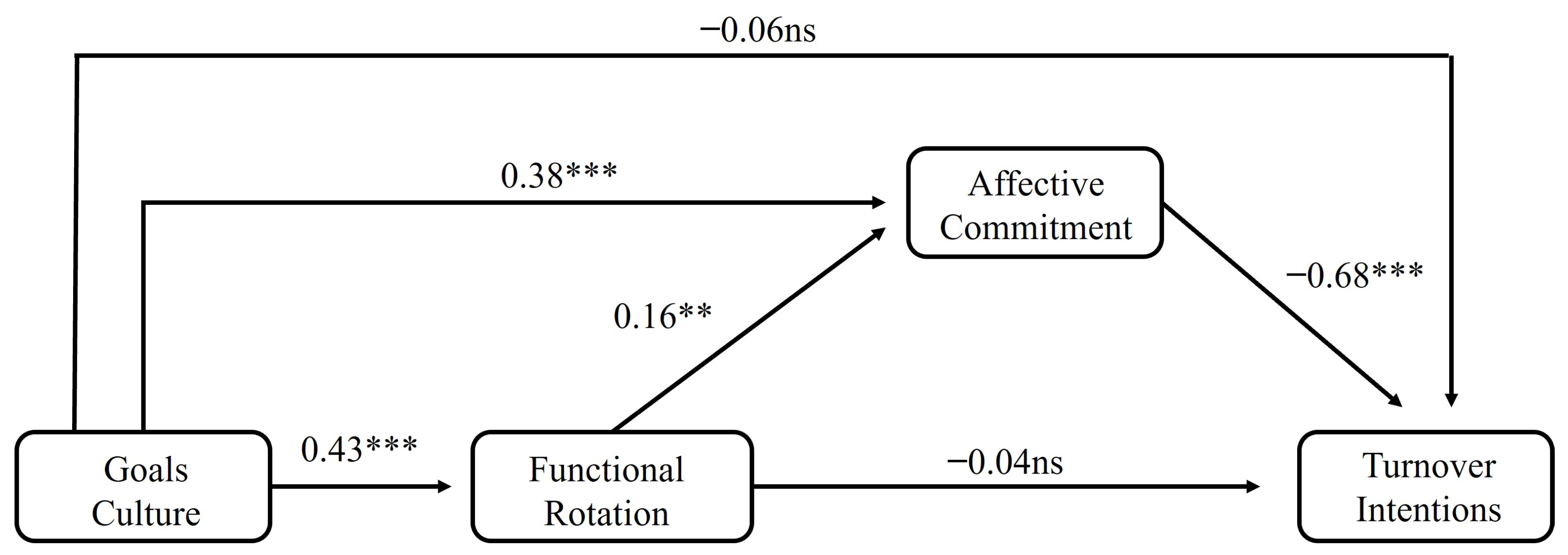

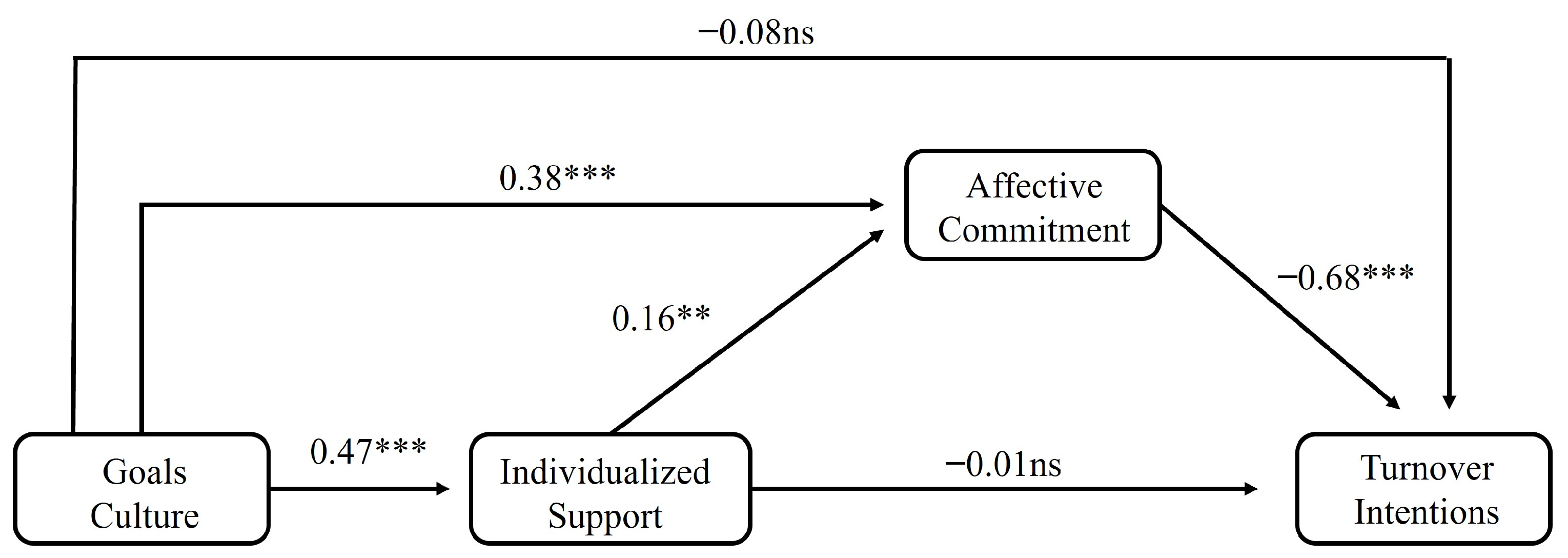

Meyer and Allen 1991). The serial mediating effect of the culture of organizational practices of development competencies (training, functional rotation and individualized support) on the relationship between goal culture and turnover intentions was also proven. When the predominant culture in an organization is one of objectives, there is a concern with developing the competencies of its employees so that they can achieve the objectives proposed by the organization (

Niguse 2019;

Pinho et al. 2013), which will cause levels of affective commitment to increase (

Moreira et al. 2024) and turnover intentions to decrease (

Benson 2006;

Mashile et al. 2019;

Meyer and Allen 1991).

Analyzing the position of the answers given by the participants in this study, the culture perceived to be the highest in Portugal is the culture of rules, followed by the supportive culture, goal culture and finally, the culture of innovation. These results are in line with the study carried out by

Salvador et al. (

2022). They are also in line with Hofstede’s study (1991), which states that Portugal is a country with high hierarchical distance, collectivism and a high aversion to uncertainty. The high hierarchical distance may be related to the culture of rules having the highest perception. In turn, the fact that we are collectivist may be related to the high levels of support culture and the aversion to uncertainty to the low perception of innovation culture.

As for the organizational practices of development competencies, the answers given by the participants are significantly below the central point of the scale, which indicates their low perception of the organizations’ concern with developing their competencies. This low perception of the organizational practices of development competencies is also in line with the results obtained by

Moreira et al. (

2024).

Whitener (

2001) states that sometimes, these practices exist in the organization but are not perceived by employees as they would like them to be. The practice with the highest perception is training, which may be related to the fact that it is the practice that organizations use most often (

Ludwikowski et al. 2018).

5.1. Limitations and Future Research

This study has some limitations. The first limitation is the data collection procedure, which was non-probabilistic, intentional and of a snowball nature, which does not allow us to generalize the data to the population. The second limitation is that this is a cross-sectional study, so it is impossible to establish causal relationships. As a third limitation, the fact that self-report questionnaires were used is another limitation of this study. To reduce the impact of common method variance, we followed several methodological recommendations from

Podsakoff et al. (

2003).

We must also consider the number of participants in this study (369). We suggest replicating it with a considerably larger number of participants.

It would be interesting to replicate this study by testing the moderating effects of certain variables on these relationships. Among the variables we could consider to test the moderating effect are the work regime (face-to-face, remote or hybrid), emotional intelligence and resilience. It would also be interesting to see if there are statistically significant differences depending on the area of the country where the employee works, as in the study by

Salvador et al. (

2022), the differences were significant. Another indication is that other variables should be considered, such as the sector of activity to which the organization belongs and its size.

Although this study has made a positive contribution to understanding the relationships between organizational culture, turnover intentions, organizational practices of competencies development and affective commitment, the limitations mentioned will be important for future research so that organizations can obtain more information and practical insights to apply to human resource management and improve their long-term success.

5.2. Practical Implications

The strength of this study is that it proved that the organizational practices of competencies development (training, functional rotation and individualized support) and affective commitment are the mechanisms that explain the relationship between goal culture and turnover intentions. It was also found that the organizational practices of competencies development (functional rotation and individualized support) and affective commitment are the mechanisms that explain the relationship between support culture and turnover intentions.

At a time when organizations are struggling with the high turnover of highly specialized employees, they should be concerned about retaining their best employees, as these are resources that are difficult to imitate and, according to the ‘Resource-Based View’ theory (

Afiouni 2007;

Barney 1991), are their competitive advantage in today’s labor market. Organizations should be concerned with fostering a greater culture of support and goals so that their perception that the organization cares about their skills development is higher (

Niguse 2019;

Pinho et al. 2013), thus boosting their affective commitment (

Moreira et al. 2024) and reducing their intentions to leave (

Benson 2006;

Mashile et al. 2019;

Meyer and Allen 1991).

This study significantly contributes to human resource management in an organization. It highlights the importance of a healthy, supportive work environment where employees are valued and promotes an organizational culture that strengthens employees’ affective commitment to the organization. The measures presented will reduce turnover intentions, minimize the costs associated with turnover and improve organizational performance.

Managers should focus on developing an inclusive and supportive culture where employees feel appreciated in their workplace and have opportunities to develop skills aligned with their professional growth. This will strengthen employees’ emotional commitment to the organization, their engagement, motivation and loyalty—all very important points for the organization’s long-term success.