Next Level Quotas? Corporate and Public Support for Gender Quotas in Executive Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

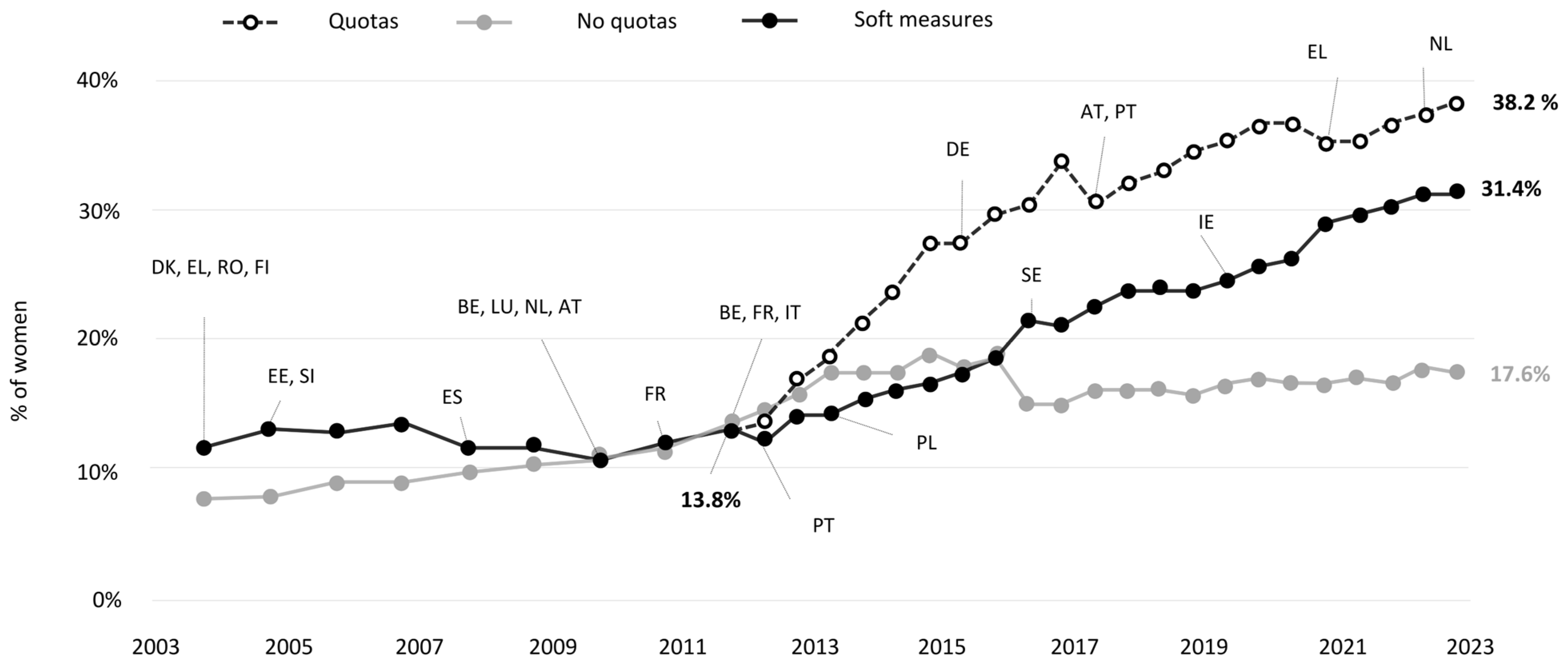

1.1. Gender Quota Laws and Company Boards

1.1.1. Introduction of Quotas, Their Objectives, and Effects

1.1.2. New European Union Legislation

1.2. Attitudes toward Gender Quotas

1.3. Spillover Effect

2. Methods

2.1. Interviews with Women and Men Sitting on the Boards of All Listed Companies

2.2. Online Panel for the General Public

3. Results

3.1. Qualitative Results: Interviews with Women and Men on Corporate Boards

3.1.1. A Temporary EGQ Is Necessary

I was very much against gender quotas for boards until I turned forty. Because I was somehow just: I’m doing well, everything is going great, and if I work as hard as the boys, I get the same rewards. Then, when I was like forty, then suddenly like, oh!?! Looking around, yes, it’s obvious, you know, even if I’m doing great, not everyone is doing great. My view just switched, just like that.

I think this legislation has been thoroughly validated, and it’s incredibly good that it was enacted. You can just see what has changed […] I think this idea sounds just as weird as the idea of gender quotas on boards sounded at the time, but why not? You know, what happened is that when this law was passed for the boards, it became much clearer that it was necessary to look for people of both genders. Then it was, like, “We need a candidate with this experience, and based on what the board looks like now, it would be best that it was a woman.” I mean, otherwise, it would just not have been done. Because, of course, they also do exist, they do have this competence, and so on. So, I think it would be just fine. There’s nothing wrong with that.

I think the gender quota was just such a necessary tipping point for the board seats […] I envision that a gender quota for the executive management teams would encourage people to choose much more carefully […] I think it just needs to be done. Naturally I am a person who just thinks that businesses should have certain freedoms and so on. A tipping point is just needed because this is a kind of market failure that just needs to be remedied by legislation for some years. Because you remember how big an issue it was before the board gender quota. I feel that no one worries about that today. I don’t think so; I think that this market failure just needs to be fixed.

3.1.2. Opposition to EGQs

I think it is not actually a problem like people are trying to make it […] there was a period when there were fewer women in the stock exchange. But now there are a few […] and just a nice balance today […] the advancement of men will become a concern in about 20 years.

I haven’t noticed anything but quite a strong will to do so […] There is a lot of impatience […] I would think that over the next three to five years you can expect that this will become more balanced.

I think it’s sort of humiliating that there must be a quota. […] two employee representatives were appointed and then […] two women, and then the men just formed their club separate from this. I didn’t feel that the board was really in charge. It just was like this. It looked quite good from the outside, but on the inside, it wasn’t good.

I wasn’t in favor of gender quotas for boards. I somehow just felt like, you know … the most qualified should just be selected. But then it dawns on you: hey, the most qualified isn’t being selected! So, it’s just bullshit, you know. I just made a U-turn.

3.2. Quantitative Results: Online Panel for the General Public

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adams, Renée B., and Tom Kirchmaier. 2013. From Female Labour Force Participation to Boardroom Gender Diversity. Financial Markets Group Discussion Paper, No. 715. Available online: https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/119038/1/DP715.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Amendments to the Act on Public Limited Companies, and the Act on Private Limited Companies Bill No. 71/2009-2010. n.d. Available online: http://www.althingi.is/altext/138/s/0071.html (accessed on 28 May 2024). (In Icelandic).

- Arnardóttir, Auður Arna, and Þröstur Olaf Sigurjónsson. 2022. Impact of Gender Quotas on Board Dynamics According to Board Members. Research in Applied Business and Economics 19: 75–94. (In Icelandic). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atinc, Guclu, Saurabh Srivastava, and Sonia Taneja. 2022. The Impact of Gender Quotas on Corporate Boards: A Cross-Country Comparative Study. Journal of Management and Governance 26: 685–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelsdóttir, Laufey, Þorgerður J. Einarsdóttir, and Guðbjörg Linda Rafnsdóttir. 2023. Justice and Utility: Approval of Gender Quotas to Increase Gender Balance in Top-Level Management—Lessons from Iceland. Gender, Work, and Organization 30: 1218–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennouri, Moez, Chiara De Amicis, and Sonia Falconieri. 2020. Welcome on Board: A Note on Gender Quotas Regulation in Europe. Economics Letters 190: 109055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, Marianne, Sandra E. Black, Sissel Jensen, and Adriana Lleras-Muney. 2019. Breaking the Glass Ceiling? The Effect of Board Quotas on Female Labour Market Outcomes in Norway. The Review of Economic Studies 86: 191–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilimoria, Diana. 2006. The Relationship Between Women Corporate Directors and Women Corporate Officers. Journal of Managerial Issues 18: 47–61. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, Pallab Kumar, Larelle Chapple, Helen Roberts, and Kevin Stainback. 2023. Board Gender Diversity and Women in Senior Management. Journal of Business Ethics 182: 177–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaca, Sara Falcao, Maria Joao Guedes, Susana Ramalho Marques, and Nuno Paço. 2022. Shedding Light on the Gender Quota Law Debate: Board Members’ Profiles Before and After Legally Binding Quotas in Portugal. Gender in Management 37: 1026–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, Silvana. 2023. Women on Boards Quotas, Targets, and Their Unintended Effects: Evidence from the United Kingdom. The Journal of Business Diversity 23: 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, Jannick Friis, and Sara Louise Muhr. 2019. H(a)unting Quotas: An Empirical Analysis of the Uncanniness of Gender Quotas. Ephemera: Theory & Politics in Organization 19: 77–105. Available online: http://www.ephemerajournal.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/contribution/19-1christensenmuhr%20%281%29.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2024).

- Christiansen, Þóra H., Ásta Dís Óladóttir, Erla S. Kristjánsdóttir, and Sigrún Gunnarsdóttir. 2021. CEO Hiring in Public Interest Entities: Biased, Exclusionary and Unprofessional Hiring Processes? Icelandic Review of Politics and Administration 17: 107–30. (In Icelandic). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, Alison, and Christy Glass. 2015. Diversity Begets Diversity? The Effects of Board Composition on the Appointment and Success of Women CEOs. Social Science Research 53: 137–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, Juliet, and Anselm Strauss. 1998. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Creditinfo. 2024. Kynjakvóti í Stjórnum Íslenskra Fyrirtækja. Creditinfo. March 1. Available online: https://blogg.creditinfo.is/kynjakvoti-i-stjornum-islenskra-fyrirtaekja/ (accessed on 18 July 2024). (In Icelandic).

- Dahlerup, Drude. 2006. Introduction. In Women, Quotas and Politics. Edited by Drude Dahlerup. London: Routledge, pp. 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Piña, María Isabel, Óscar Rodríguez-Ruiz, Antonio Rodríguez-Duarte, and Miguel Ángel Sastre-Castillo. 2020. Gender Diversity in Spanish Banks: Trickle-Down and Productivity Effects. Sustainability 12: 2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte. 2022. Progress at a Snail’s Pace: Women in the Boardroom—A Global Perspective, 7th ed. London: Deloitte Global Boardroom Program. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/nl/Documents/AtB/deloitte-nl-women-in-the-boardroom-seventh-edition.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- De Vita, Luisa, and Antonella Magliocco. 2018. Effects of Gender Quotas in Italy: A First Impact Assessment in the Italian Banking Sector. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 38: 673–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolgin, Elie. 2017. Gender Tokenism and Bias Prevail in Biotech Boardrooms. Nature Biotechnology 35: 185–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsdóttir, Þorgerður J., Guðbjörg Linda Rafnsdóttir, and Margrét Valdimarsdóttir. 2020. Structural Hindrances or Less Driven Women? Managers’ Views on Corporate Quotas. Politics & Gender 16: 285–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Morgan, and Meggin T. Eastman. 2018. Women on Boards: Progress Report 2018. New York: MSCI. Available online: https://www.msci.com/documents/10199/36ef83ab-ed68-c1c1-58fe-86a3eab673b8 (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- Esterberg, Kristin G. 2002. Qualitative Methods in Social Research. London: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE). 2023. Largest Listed Companies: Presidents, Board Members and Employee Representatives. Available online: https://eige.europa.eu/gender-statistics/dgs/indicator/wmidm_bus_bus__wmid_comp_compbm/datatable (accessed on 2 April 2024).

- European Union. 2023. 2023 Report on Gender Equality in the EU. Brussels: European Union. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2023-04/annual_report_GE_2023_web_EN.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2024).

- Ferrari, Giulia, Valeria Ferraro, Paola Profeta, and Chiara Pronzato. 2022. Do Board Gender Quotas Matter? Selection, Performance, and Stock Market Effects. Management Science 68: 5618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, Uwe. 2004. Triangulation in Qualitative Research. In A Companion to Qualitative Research. Edited by Uwe Flick, Ernst von Kardoff and Ines Steinke. London: Sage, pp. 178–83. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Blandon, Josep, Josep Maria Argilés-Bosch, Diego Ravenda, and David Castillo-Merino. 2023. Direct and Spillover Effects of Board Gender Quotas: Revisiting the Norwegian Experience. Business Ethics, the Environment & Responsibility 32: 1297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geletkanycz, Martha A. 2020. Social Movement Spillover: Barriers to Board Gender Diversity Posed by Contemporary Governance Reform. Leadership Quarterly 31: 101438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GemmaQ. 2024. The Proportion of Women in Managerial Positions Decreases, GemmaQ in March 2024: The Number of Female Executives Declines. March 26. Available online: https://gemmaq.co/gemmaqiceland?fbclid=IwZXh0bgNhZW0CMTAAAR0Yu6Cdt9Dg_Hw9dZFVAj-U9cp-el9jjoeCUXaKjF-SrMTXvgIcMs3UJss_aem_C_SPlA6RkUQDEiNcPCxgAQ (accessed on 10 July 2024). (In Icelandic).

- Gibert, Anna, and Alexandra Fedorets. 2024. Lifting Women Up: Gender Quotas and the Advancement of Women on Corporate Boards. Corporate Governance: An International Review, Epub ahead of printing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, Jill A., Carol T. Kulik, and Shruti R. Sardeshmukh. 2018. Trickle-Down Effect: The Impact of Female Board Members on Executive Gender Diversity. Human Resource Management 57: 931–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halrynjo, Sigtona, and Mari Teigen. 2024. Gender Quotas for Corporate Boards: Do They Lead to More Women in Senior Executive Management? Gender in Management 39: 761–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humbert, Anne Laure, Elisabeth K. Kelan, and Kate Clayton-Hathway. 2019. A Rights-Based Approach to Board Quotas and How Hard Sanctions Work for Gender Equality. European Journal of Women’s Studies 26: 447–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R. Burke, and Anthony J. Onwuegbuzie. 2004. Mixed Methods Research: A Research Paradigm Whose Time Has Come. Educational Researcher 33: 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavalieraki-Foka, Dimitra, Sofia Asonitou, Chara Kottara, Fragkiskos Gonidakis, and George Giannopoulos. 2024. Corporate Boards and Gender Quotas: A Review of Literature. In Strategic Innovative Marketing and Tourism. Edited by Androniki Kavoura, Teresa Borges-Tiago and Flavio Tiago. Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics. Cham: Springer, pp. 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Hyondong, and Yongsang Kim. 2023. The Effects of Gender Diversity in Boards of Directors on the Number of Female Managers Promoted. Baltic Journal of Management 18: 122–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsch, Anja. 2021. Women on Boards Policies in Member States and the Effects on Corporate Governance. Brussels: European Parliament. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2021/700556/IPOL_STU(2021)700556_EN.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Latura, Audrey, and Ana Catalano Weeks. 2023. Corporate Board Quotas and Gender Equality Policies in the Workplace. American Journal of Political Science 67: 606–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandatory Insurance of Pension Rights and the Operation of Pension Funds Act No. 156/2011. n.d. Available online: https://www.stjornartidindi.is/Advert.aspx?ID=11d81b49-236b-4868-80b1-12d0d4dc688b (accessed on 16 January 2024). (In Icelandic).

- Matsa, David A., and Amalia R. Miller. 2011. Chipping Away at the Glass Ceiling: Gender Spillovers in Corporate Leadership. The American Economic Review 101: 635–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensi-Klarbach, Heike, and Cathrine Seierstad. 2020. Gender Quotas on Corporate Boards: Similarities and Differences in Quota Scenarios. European Management Review 17: 615–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam, Sharan B., and Elizabeth J. Tisdell. 2016. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation, 4th ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Óladóttir, Ásta Dís. 2023. Við töpum öll á einsleitninni, jafnrétti er ákvörðun. FKA. October 12. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=701Sx9KSM74&t=1861s (accessed on 4 December 2023).

- Óladóttir, Ásta Dís, Þóra H. Christiansen, and Gylfi Dalmann Aðalsteinsson. 2021. If Iceland Is a Gender Paradise, Where Are the Women CEOs of Listed Companies? In Exploring Gender at Work: Multiple Perspectives. Edited by Joan Marques. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 317–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Óladóttir, Ásta Dís, Thora H. Christiansen, Sigrún Gunnarsdóttir, and Erla S. Kristjánsdóttir. 2024. Closing the Gap—TMT Quotas, Investment Strategies, and Succession Policies for Gender Equality. In Encyclopedia of Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Spirituality. Edited by Joan Marques. Cham: Springer, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, Aaron, Ruth Sealy, Andrew Parker, and Oliver Hauser. forthcoming. Regulation and the Trickle-Down Effect of Women in Leadership Roles. Leadership Quarterly, in press. [CrossRef]

- Private Limited Companies Act no. 13/2010. n.d. Available online: https://www.althingi.is/altext/stjt/2010.013.html (accessed on 5 December 2023). (In Icelandic).

- Rafnsdóttir, Gudbjörg Linda, and Margrét Þorvaldsdóttir. 2012. Gender Quotas and Possible Barriers to Women’s Path to Top Management”. The Icelandic Society 3: 57–76. Available online: https://ojs.hi.is/index.php/tf/article/view/3747 (accessed on 5 December 2023). (In Icelandic).

- Rafnsdóttir, Gudbjörg Linda, Thorgerdur Einarsdóttir, and Jón Snorri Snorrason. 2014. Gender Quotas on the Boards of Corporations in Iceland. In Gender Quota for the Boards. Edited by Marc De Vos and Philippe Culliford. Cambridge: Intersentia, pp. 147–57. [Google Scholar]

- Rebérioux, Antoine, and Gwénaël Roudaut. 2019. The Role of Rookie Female Directors in a Post-Quota Period: Gender Inequalities within French Boards. IDEAS Working Paper Series from RePEc 58: 423–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamon, Lester M. 2002. The Tools of Government: A Guide to the New Governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Seierstad, Cathrine, Geraldine Healy, Eskil Sonju Le Bruyn, and Hilde Fjellvær. 2021. A ‘Quota Silo’ or Positive Equality Reach? The Equality Impact of Gender Quotas on Corporate Boards in Norway. Human Resource Management Journal 31: 165–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaggs, Sheryl, Kevin Stainback, and Phyllis Duncan. 2012. Shaking Things up or Business as Usual? The Influence of Female Corporate Executives and Board of Directors on Women’s Managerial Representation. Social Science Research 41: 936–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics Iceland. 2023. Gender of CEOs and Board Members by Company Size 1999–2022 [Data]. Reykjavík: Statistics Iceland. Available online: https://hagstofa.is (accessed on 18 January 2024).

- Statistics Norway. 2024. Board and Management in Limited Companies. April 29. Available online: https://www.ssb.no/en/virksomheter-foretak-og-regnskap/eierskap-og-roller/statistikk/styre-og-leiing-i-aksjeselskap (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Storvik, Aagoth, and Mari Teigen. 2010. Women on Board: The Norwegian Experience. Bonn and Berlin: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung. Available online: https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/id/ipa/07309.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2023).

- Sustainable Development Goals. 2024. Ensure Women’s Full and Effective Participation and Equal Opportunities for Leadership at All Levels of Decision-Making in Political, Economic, and Public Life. April 28. Available online: https://www.heimsmarkmidin.is/default.aspx?pageid=60627105-3f21-4a9f-8f88-def1241557ec (accessed on 3 June 2024).

- Teigen, Mari. 2003. Kvotering til Styreverv: Mellom Offentlig Regulering og Privat Handlefrihet. Tidskrift for Samfunnsforskning 43: 73–104. (In Norwegian). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teigen, Mari. 2015. The Making of Gender Quotas for Corporate Boards in Norway. In Cooperation and Conflict the Nordic Way. Edited by Fredrik Engelstad and Anniken Hagelund. Berlin: De Gruyter Open, pp. 96–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teigen, Mari. 2022. Gender Quotas for Corporate Boards: A Qualified Success in Changing Male Dominance in the Boardroom. In Successful Public Policy in the Nordic Countries: Cases, Lessons, Challenges. Edited by Caroline de la Porte, Guðný Björk Eydal, Jaakko Kauko, Daniel Nohrstedt, Paul t‘ Hart and Bent Sofus Tranøy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teigen, Mari, and Liza Reisel. 2017. Kjønnsbalanse på Toppen? Sektorvariasjon i Næringsliv, Akademia, Offentlig Sektor og Organisasjonsliv. Oslo: Institutt for samfunnsforskning. Available online: https://samfunnsforskning.brage.unit.no/samfunnsforskning-xmlui/bitstream/handle/11250/2473133/Rapport_11-17_web.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2024). (In Norwegian)

- Terjesen, Siri, Ruth V. Aguilera, and Ruth Lorenz. 2015. Legislating a Woman’s Seat on the Board: Institutional Factors Driving Gender Quotas for Boards of Directors. Journal of Business Ethics 128: 233–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Economist. 2014. The Spread of Gender Quotas for Company Boards. The Economist. March 25. Available online: https://www.economist.com/the-economist-explains/2014/03/25/the-spread-of-gender-quotas-for-company-boards (accessed on 13 June 2024).

- The World Bank. 2024. Women, Business and the Law 2024. Washington, DC: The World Bank. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstreams/9bc44005-2490-41f8-b975-af35cbae8b9a/download (accessed on 4 July 2024).

- World Economic Forum. 2024. Global Gender Gap Report 2024. Cologny: World Economic Forum. Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2024.pdf (accessed on 6 July 2024).

- Zattoni, Alessandro, Stergios Leventis, Hans Van Ees, and Sara De Masi. 2023. Board Diversity’s Antecedents and Consequences: A Review and Research Agenda. Leadership Quarterly 34: 101659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | Approved | Minimum Rate | “Comply or Explain” or Mandatory | Sanctions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 2018 | 30% | Mandatory | Yes |

| Belgium | 2011 | 33% | Mandatory | Yes |

| Denmark | 2013 | 40% | Comply or explain | No |

| Finland | 2008 | At least one woman | Comply or explain | No |

| France | 2017 | 40% | Mandatory | Yes |

| Germany | 2015 | 30% | Mandatory | Yes |

| Greece | 2021 | 25% | Mandatory | Yes |

| Iceland | 2010 | 40% | Mandatory | No |

| Italy | 2019 | 40% | Mandatory | Yes |

| Netherlands | 2021 | 33% | Mandatory | Yes |

| Norway | 2003 | 40% | Mandatory | Yes |

| Portugal | 2018 | 33% | Mandatory | Yes |

| Spain | 2020 | 40% | Comply or explain | No |

| Switzerland | 2021 | 30% | Mandatory | No |

| M | SD | Min | Max | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men and women have equal opportunities to obtain CEO or senior management positions in Icelandic companies. | 3.25 | 1.38 | 1 | 5 | |

| The government should impose gender quota laws on the executive management teams of companies with more than 50 employees. | 3.00 | 1.29 | 1 | 5 | |

| Gender quota laws for executive management teams reduce the likelihood of the most qualified individuals being selected for executive management teams. | 3.19 | 1.27 | 1 | 5 | |

| It is taking too long to achieve gender balance in the top management level in Icelandic business. | 3.55 | 1.20 | 1 | 5 | |

| In politics, how would you rank yourself on a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 is furthest to the left and 10 is furthest to the right in politics? | 4.72 | 2.24 | 0 | 10 | |

| Age | |||||

| 18–25 years | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0 | 1 | |

| 26–35 years | 0.20 | 0.40 | 0 | 1 | |

| 36–45 years | 0.18 | 0.39 | 0 | 1 | |

| 46–55 years | 0.16 | 0.37 | 0 | 1 | |

| 56–65 years | 0.15 | 0.36 | 0 | 1 | |

| 66–75 years | 0.11 | 0.31 | 0 | 1 | |

| 76 years old or older | 0.07 | 0.26 | 0 | 1 | |

| Highest educational level | |||||

| Primary school | 0.25 | 0.44 | 0 | 1 | |

| Secondary school | 0.38 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 | |

| University | 0.37 | 0.48 | 0 | 1 | |

| Residence | |||||

| Rural areas | 0.35 | 0.48 | 0 | 1 | |

| Capital region | 0.65 | 0.48 | 0 | 1 | |

| Female | Male | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | N | M | SD | N | |

| Men and women have equal opportunities to obtain CEO or senior management positions in Icelandic businesses | 2.84 | 1.38 | 490 | 3.66 | 1.26 | 497 |

| The government should impose gender quota laws on the executive management teams of companies with more than 50 employees | 3.47 | 1.11 | 470 | 2.54 | 1.28 | 478 |

| Gender quota laws for executive management teams reduce the likelihood of the most qualified individuals being selected for executive management teams | 2.85 | 1.21 | 467 | 3.53 | 1.24 | 483 |

| It is taking too long to achieve gender balance at the top management level in Icelandic companies | 4.00 | 0.95 | 485 | 3.12 | 1.26 | 499 |

| b | β | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 3.17 | <0.001 | |

| Female | 0.26 | 0.10 | <0.001 |

| Age | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.414 |

| Highest educational level | |||

| Secondary school | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.827 |

| University | −0.19 | −0.07 | 0.016 |

| Capital region | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.822 |

| Political ranking from left to right | −0.06 | −0.10 | <0.001 |

| Men and women have equal opportunities to obtain CEO or senior management positions in Icelandic businesses | −0.06 | −0.07 | 0.019 |

| Gender quota laws for executive management teams reduce the likelihood of the most qualified individuals being selected for executive management teams | −0.38 | −0.37 | <0.001 |

| It is taking too long to achieve gender balance at the top management level in Icelandic companies | 0.41 | 0.39 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Óladóttir, Á.D.; Christiansen, T.H.; Gylfason, H.F.; Benediktsson, H.C.; Thorarinsdottir, F.V. Next Level Quotas? Corporate and Public Support for Gender Quotas in Executive Management. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14090209

Óladóttir ÁD, Christiansen TH, Gylfason HF, Benediktsson HC, Thorarinsdottir FV. Next Level Quotas? Corporate and Public Support for Gender Quotas in Executive Management. Administrative Sciences. 2024; 14(9):209. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14090209

Chicago/Turabian StyleÓladóttir, Ásta Dís, Thora H. Christiansen, Haukur Freyr Gylfason, Haukur C. Benediktsson, and Freyja Vilborg Thorarinsdottir. 2024. "Next Level Quotas? Corporate and Public Support for Gender Quotas in Executive Management" Administrative Sciences 14, no. 9: 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14090209

APA StyleÓladóttir, Á. D., Christiansen, T. H., Gylfason, H. F., Benediktsson, H. C., & Thorarinsdottir, F. V. (2024). Next Level Quotas? Corporate and Public Support for Gender Quotas in Executive Management. Administrative Sciences, 14(9), 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14090209