5. Discussion and Conclusions

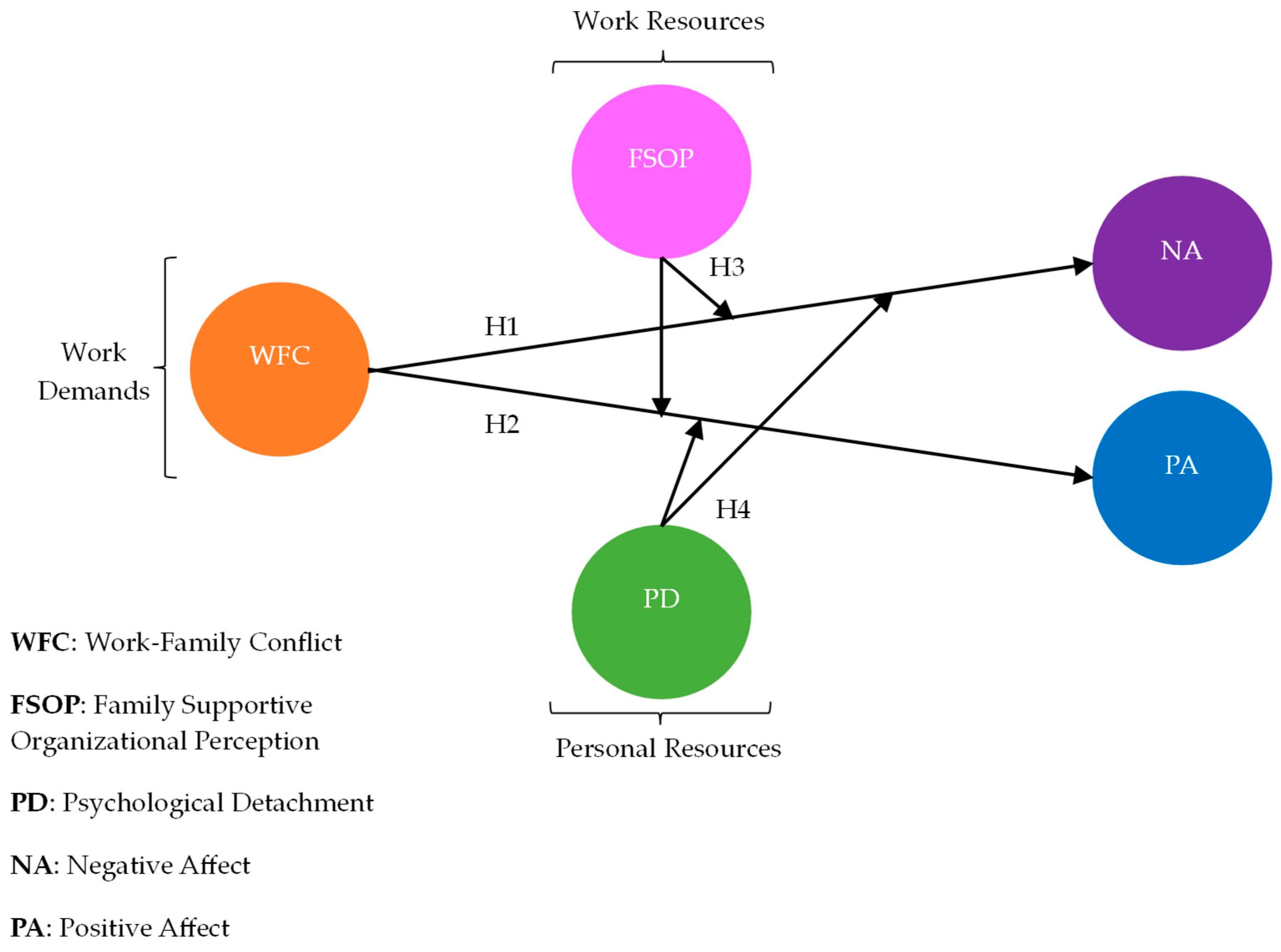

The primary objective of this study was to investigate the psychological mechanisms underlying the health impairment process in the JD-R model. Given the significance of positive and negative affect in the workplace and home settings, the study examined the relationships between these affect states, work–family conflict, and the moderating roles of family-supportive organizational perceptions and psychological detachment.

The pattern of correlations was rather similar between men and women. The correlations between FSOP and PA, however, diverge between genders, being non-significant for men and positively correlated for women. These differences can be discussed in light of the Boundary Theory (

Clark 2000), which suggests a greater tendency for women to integrate both domains of their adult life. In the case of men, as their social roles are more separated, there may be less conflict, and thus, the availability of supportive resources may be perceived as less essential.

Our findings supported our initial two hypotheses. Specifically, we found that high levels of work–family conflict were associated with an increase in negative affect and a decrease in positive affect. These results align with the JD-R model and are consistent with previous research highlighting the connections between work–family conflict and negative affect (

Cetin et al. 2021;

French and Allen 2020;

Gryzwacz et al. 2004;

Judge et al. 2006). Furthermore, our findings contribute to the relatively limited literature demonstrating a relationship between positive affect and work–family conflict (

Cetin et al. 2021;

Davis et al. 2016;

Sandrin et al. 2020).

Another objective of our study was to examine the role of family-supportive organizational perceptions as a job resource and psychological detachment as a personal resource in our previously confirmed relationships. However, our third hypothesis, which posited that the perception of a family-supportive organization would mitigate the impact of work–family conflict on positive and negative affect, was not supported. This was somewhat unexpected as it contradicts the JD-R model and previous studies that established this relationship (e.g.,

George et al. 1993;

Mauno et al. 2007). In line with the conservation of resources theory (

Hobfoll 1989), it would be expected that during periods of heightened tension and personal resource investment, the disposition to regain, replace, and acquire resources would be amplified (

Salanova et al. 2006). Consequently, organizational support should have been perceived as an avenue for resource acquisition. This raises the prospect that FSOP may not be acknowledged as a valuable resource in managing the work–family conflict relationship and its affective consequences.

Other explanations can be considered for these results. One potential justification relates to our sample composition. Our participants, both men and women, primarily work for small companies compared to medium and large organizations. The literature suggests that the perception of organizational support tends to be higher in larger organizations (

Ortiz-Isabeles and García-Avitia 2022). Larger companies typically have more comprehensive feedback systems, better employee tracking, and a greater sense of recognition, likely due to their superior financial resources and resource allocation capabilities (

Hayton et al. 2012;

Hutchison and Garstka 1996). Consequently, in smaller-sized companies, the perception of family-friendly support may not be robust enough to buffer the effects of work–family conflict on affect.

Another interpretation pertains to the implications of receiving support from the professionals’ perspective. According to

Walsh and Cormack (

1994), while professionals often express their support needs, receiving support can generate feelings of inequity, vulnerability, and powerlessness, posing a threat to self-esteem (

Buunk and Hoorens 1992;

Coyne and DeLongis 1986;

Fisher et al. 1982;

Stewart 1989). Therefore, receiving support may also adversely affect individuals, hindering the reduction in the negative impact of work–family conflict on affect.

It is worth noting that the moderation effect for men was nearly significant, raising questions about the power of our analyses. As a result, future research may benefit from replicating this study to provide further insights into these relationships.

Our final hypothesis (H4) posited that psychological detachment would mitigate the impact of work–family conflict on positive and negative affect. Our findings partially supported this hypothesis, as psychological detachment was found to buffer the effect of work–family conflict on negative affect for women.

The Boundary Theory (

Allen and French 2023;

Ashforth et al. 2000;

Clark 2000) offers insight into these gender differences observed in our results. This theory suggests that individuals establish and maintain temporal, physical, and psychological boundaries to simplify and structure their environment. The gender disparities in our study may be attributed to the greater tendency among women to integrate both their work and family roles, leading to blurred boundaries between these domains (

Kossek et al. 1999). This inclination is influenced by differing societal expectations regarding how work and family responsibilities should be jointly managed for men and women. While gender roles have evolved to become more balanced over time, women continue to bear a heavier load in the family domain, including household responsibilities. This increased responsibility results in women’s roles being more intertwined, making the boundaries between work and family more permeable and flexible in terms of time and physical space. As a result, women are better equipped to meet the demands of both roles (

Ghislieri et al. 2017;

Nsair and Piszczek 2021). Consequently, women may place more value on the ability to psychologically detach from work, seeing it as a more critical need than men.

Conversely, the observed gender differences in our study may also be attributed to variations in emotional regulation strategies. Various theoretical models have identified specific strategies as either adaptive or maladaptive over time (

Aldao et al. 2010). Following Gross’s model (1995), response-focused strategies concentrate on regulating emotions after the initial trigger has occurred, in this case, WFC. It is common for individuals to engage in rumination, a phenomenon characterized by repetitive focus on the emotional experience, its causes, and consequences and often stems from individuals’ intentions to understand and resolve their concerns. However, in distressing situations, rumination has been shown to hinder effective problem-solving, which, oppositely, would be an adaptive response-focused strategy (

Aldao and Nolen-Hoeksema 2010). Thus, rumination, a maladaptive coping mechanism, is often more prevalent among women (

Ando et al. 2020;

Calderwood et al. 2018;

Demsky et al. 2019). The existing literature has consistently highlighted that women tend to engage in negative rumination about work, which can disrupt the restoration of psychophysiological systems during non-working hours (

Demsky et al. 2019;

Calderwood et al. 2018). In this context, psychological detachment may serve as an opportunity for women to interrupt these rumination processes, promoting better recovery.

Furthermore, our results indicate that the number of hours worked per week significantly affects men, not women. This can be explained by the fact that men, compared to women, may be better able to compartmentalize their work and family domains, largely due to experiencing fewer family demands (

Nsair and Piszczek 2021;

Rothbard 2001). Men’s capacity to segment these domains may be strained when they work longer hours, which, in turn, can diminish their positive affect. It is essential to acknowledge that societal gender norms also play a role in shaping these dynamics. Men often face social expectations that prioritize work over family commitments, making it less socially acceptable for them to prioritize their family roles over work responsibilities (

Rothbard 2001). Consequently, they might endure the demands of their jobs due to these societal pressures, ultimately leading to a reduction in their positive affect.

Incorporating individual strategies into the JD-R theory holds theoretical and practical significance, shedding light on behaviors that facilitate optimal functioning in specific work contexts. This insight can guide organizations in promoting or training these behaviors (

Bakker and Demerouti 2017). Therefore, organizations must recognize the significance of psychological detachment. This can be achieved through adjustments to work schedules, the provision of more breaks, offering leisure opportunities and activities, imparting emotional management skills to employees (

Moreno-Jiménez et al. 2009), and fostering a culture that supports the differentiation between work and non-work life (

Sonnentag et al. 2008). These practices are particularly important for female workers, as highlighted by our study.

These findings hold important theoretical implications as well. By encouraging the integration of different psychological mechanisms, such as affect, into the relationship between job demands and strain, we contribute to the refinement and advancement of the JD-R model. Affective experiences have a profound impact on both psychological and physical well-being. When specific emotions are triggered due to the associated physiological arousal, they can also drive behavioral tendencies, a concept of great interest in organizational psychology theory (

Galinha et al. 2014;

Weiss and Cropanzano 1996) and work–family conflict theory.

This study also yields practical implications. As previously established, the JD-R model posits that each profession possesses distinct working characteristics, categorizable as demands or resources (

Bakker and Demerouti 2007). This makes it an applicable model to a wide array of occupational contexts, with particular relevance to professions where work–family conflict is a well-established demand (e.g., police officers, firefighters, health professionals). Moreover, the escalating prevalence of work–family conflict (WFC), propelled by multifaceted factors and its impact on well-being, points to potential effects on both positive and negative affect. Understanding these associations may help shape interventions, policies, practices, and organizational cultures that enable employees to navigate the core domains of their lives (

Davis et al. 2016;

Kossek et al. 2011a). Additionally, the affective states of workers are highly pertinent to their behavior in the organizational context. Therefore, the study of affect is crucial in understanding the relationships between affect, work attitudes, and workplace behaviors (

Fritz et al. 2010).

All organizations must proactively support their workforce to navigate these demands and develop resources for emotional regulation, promoting both mental well-being and optimal performance. This entails recognizing the importance of emotion regulation, which, as previously mentioned, encompasses conscious and unconscious processes through which individuals modulate their emotions to adaptively respond to environmental demands. Within this framework, reappraisal and problem-solving strategies are regarded as adaptive approaches to managing emotions across diverse contexts, with reappraisal involving generating positive interpretations of stressful situations, aiming to reduce distress, and problem-solving entailing conscious efforts to alter or mitigate stressors. Moreover, mindfulness, the practice of non-judgmental acceptance of emotions, has emerged as a promising regulatory strategy associated with positive outcomes, emphasizing the need for organizations to incorporate such strategies into their support systems (

Aldao et al. 2010;

Aldao and Nolen-Hoeksema 2010;

Pico et al. 2024).

The current investigation presents certain limitations that merit consideration. As most participants hold a conventional 9 h to 17 h work schedule, this may limit the applicability of our findings to settings involving non-traditional work hours, such as shift-based work. This circumstance overlooks additional challenges associated with schedules that more directly conflict with family life. Subsequent research endeavors should strive to encompass a broader spectrum of work schedules, thereby fostering a more comprehensive understanding of the explored relationships.

Moreover, most of our participants have educational qualifications equivalent to or lower than the mandated twelve years of schooling. This may signal that our sample is involved in low-skilled jobs, thus experiencing limited access to psychological support and work resources. Consequently, alternative moderators beyond organizational support or the capacity to psychologically detach from work may hold relevance. Hence, these findings may not readily extrapolate to individuals possessing higher educational attainments and qualifications.

Additionally, our data do not allow for the inference of causality between variables, particularly regarding the circular relationships between affect and perceptions of conflict. For instance, emotions exhibited at home could also influence the perception of negative work–life balance. Longitudinal studies are a valuable tool to explore these dynamics further. Furthermore, the reliance on self-reported measures might introduce common method bias. Finally, our affect measurement focused on five negative affect and three positive affect items; incorporating a more diverse array of emotional states could be beneficial to attain a broader scope.

Work–family conflict is a bidirectional concept, and to gain a more complete understanding on this phenomenon, future research should explore both directions of this conflict and their relationships with personal and work resources. Considering the impact of teamwork and examining perceptions of work characteristics at the team and department levels may also contribute to a more nuanced understanding of work–family conflict. Thus, several variables should be considered in future research, such as other forms of support. Examples encompass support derived from direct supervisors and colleagues. Direct supervisors have a more immediate influence on team conflict resolution and workload management. The perceived support from supervisors could correlate strongly with individuals’ affective states. Conversely, the team and work environment are intricately linked to the formal and informal relationships among coworkers. Thus, the support extended by peers may significantly impact an employee’s affective states. Additionally, other contextual factors necessitate consideration, such as work hours, potential time zone disparities, monthly workload variations, the families’ financial resources, and the size and accessibility of support networks. These factors often represent commonplace constraints in the interface between work and family life. Their potential to either exacerbate or alleviate an employee’s affective states may depend on the support available across these dimensions. Additionally, further research into the concept of working from home could yield valuable insights into practices that either alleviate or exacerbate work–family conflict.

In conclusion, despite the aforementioned limitations, our study contributes to the existing literature on the JD-R health-impairment process. Understanding the potential mechanisms that link work–family conflict to health is crucial for improving policies and designing targeted interventions to alleviate this source of stress in adults’ lives. Enhancing our knowledge of work practices, support systems, and organizational policies can have a positive impact on employee well-being as they navigate the intricate balance between their work and family roles (

Eng et al. 2010). By incorporating the concept of psychological detachment, we have made a valuable addition to the existing literature on recovery experiences within the context of work–family conflict and organizational psychology.