Abstract

As the relevant European Union directives require in-depth sustainability reporting from large institutions, banks are among the concerned with disclosure obligations. Several institutions prepare self-structured recommendations by which companies are indirectly fostered to make their operation more sustainable through reporting and to help compliance with the upcoming Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) regulations. However, in the preparation period, differences can be found in the actual sustainability disclosure practices across Europe (primarily by a western–eastern European relation). To examine this issue, this study aimed to investigate if there was any variation in the reporting compliance with aspects (key performance indicators—KPIs) of three reporting guidelines (Global Reporting Initiative—G4, Financial Services Sector Disclosures—GRI; Alliance for Corporate Transparency—ACT; ISO 26000:2010—ISO) between top European and Hungarian banks according to their 2021 sustainability/ESG reports, using content analysis-based disclosure scoring. The results revealed no significant differences among the general (aspect-pooled) scores for different guidelines, while the differences were significant for each guideline between the two bank groups. In the aspect-level evaluation, the European banks had higher scores in most cases, with the Hungarian banks receiving higher scores in 4 of 49 GRI, 1 of 16 ACT, and 2 of 37 ISO aspects. Significant correlations were indicated in disclosure score values between the two bank groups, which suggested similar preferences for the aspects demonstrated; however, elaboration levels differed. These findings showed that the European and Hungarian banks could be differentiated by their sustainability disclosure patterns. The results suggest a better CSRD-level preparedness of the top European banks than of the Hungarian ones, with the latter being introduced as a model group of the region. This reflects the need for more efficient adoption of best practices by financial institutions in the eastern parts of Europe.

1. Introduction

The transition toward a more sustainable economy requires a complex approach from stakeholders in which the company actors and the members of society play a vital role (Söderholm 2020). Most people are more or less tightly connected with banking institutions; thus, the requirements set and responses given by these institutions are commonly visible on a daily basis. As legal and non-legal compliance pressure on European Union banks continuously increases, institutions include increasingly more disclosure schemes in their reporting practices, giving even more importance to sustainability/ESG (environment–social–governance) issues (Dinh et al. 2023). Besides being a multi-level requirement, ESG reporting can—directly and indirectly—contribute to the company’s progress by enhancing financial performance and mitigating risk (Lopez de Silanes et al. 2019). To keep up with the latest requirements along with the milestone deadlines determined by the European Union and the national policymakers, financial institutions face various challenges depending on their micro- and macroeconomic opportunities and determined by an increasing number of crises (Borowski 2022; Loewen 2022). Some authors found that even though banking performance in Europe has not been significantly affected during the COVID-19 crisis, it has forced companies to immediately implement digital transformations for their business models (Miklaszewska et al. 2021; Agoraki et al. 2023). However, through the results of the net-of-market return approach, the energy crisis caused a decline in bank stocks in Europe by 1.4%, which hindered the evolution of previously launched transition efforts (Boubaker et al. 2023).

To foster sustainability initiatives on multiple scales, the European Union designated the road to accomplishing the 2050 goals by implementing several legal documents (e.g., directives) subordinated to Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) initiatives (Zetzsche and Anker-Sørensen 2022). As one of the first dedicated steps to give an influential reporting framework to economic stakeholders, the European Parliament and the Council implemented the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (Directive 2014/95/EU) (NFRD 2014). With the NFRD, the EU requested the concerned scope of companies to publish non-financial, ESG-related information on their operation, enabling a transparent external evaluation of their performance dedicated to sustainability. To tighten and deepen the scope of reported information, the bodies of the EU created the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (Directive 2022/2464/EU) (CSRD 2022). Through the regulations of this directive, all companies beneath its scope become obliged to report on sustainability aspects according to the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS), by which current voluntary disclosure practices will be dismissed. Listed companies have been expected to make reports since 2017; however, the adoption of the CSRD for all large companies is due on 1 January 2024. Further, the progressive involvement of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) also materializes. Following specifying the requirements for a sector with huge potential indirect environmental influence, the EU prepared the Sustainable Finance Disclosures Regulation (Directive 2020/852/EU) for financial market participants (SFDR 2020). According to the SFDR, members in the scope must include sustainability disclosures based on their products to shed light on the risks and negative environmental, social, and economic impacts these inherently pose for investors.

In close association with sustainability reporting requirements, several theories underline the importance of interconnection and communication in economic operation. For instance, the legitimacy theory is the company’s intention to focus on societal limitations and manage positive interactions (Deegan 2019). Further, the stakeholder theory addresses all the internal and external parties affected by the company’s operation, thereby recognizing its effects on multiple scales (Freeman et al. 2021; Yin et al. 2023). Additionally, on a more economic plane with some societal aspects, signaling theory is based on the fact that companies offer long-term products on the stock market, an activity that is evaluated differently in cases of bond and share issuance by potential investors, resulting in assumptions from the investors regarding the actual situation of the company (Connelly et al. 2011). As can be seen, the company management of the processes related to the stakeholders and these theories, as well as the relevant reporting schemes, are integrated parts of the everyday operation and thus highly influence the assessment and performance of the company (Habib 2023). Due to the intense attention focused on the problems of sustainability, various reporting guidelines have been developed. However, there is only a relatively limited level of knowledge regarding their relationship and the satisfaction of the criteria determined in these documents by various financial institutions.

This article is structured as follows: in the first part, we give a broad overview of the current state of the art in theory and practice of application of various ESG-reporting guidelines; then, hypotheses are formulated to understand better the practical applicability, similarities, and specific features of various reporting systems. The methodology part describes the workflow of data collection and analysis. Results and discussion are summarized in one section, and conclusions and policy applications are formulated.

2. Relevant Literature

Considering the significant changes called forth by the CSRD, the period to the end of 2023 was designated as a preparation period. Within this interval, an extensive situation assessment and the determination of gaps were intended; this was supposed to facilitate compliance with the novel expectations even in the initial phases (Nieto and Papathanassiou 2023). The guidance of these directives provides definite steps toward a transparent (in association with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs)), sustainable, and circular economy (Opferkuch et al. 2022); the issue of non-compliance, however, raises several questions. It is yet unknown if there will be a joint penalty scheme for EU countries instead of the recent various policies and, if so, to what extent the financial institutions non-compliant with the regulations will be sanctioned (European Financial Reporting Advisory Group 2021). It also cannot be assessed how sham measures (e.g., greenwashing) can efficiently be recognized and repelled to foster actual and practical implementations (Khan et al. 2021). Further, it remains unknown if most companies will be able to allocate enough resources to high-priority sustainability aspects during the preparation period and how the deadlines of execution will, in cases of unforeseeable inconveniences (e.g., future economic and societal crises), be influenced and reconsidered by the liable authorities (Broadstock et al. 2021; Hassan et al. 2021). Although action plans cannot be assigned to all possible future scenarios, recent efforts should be subordinated to global sustainability goals as the road paved by actions that enhance the resilience of financial institutions (Primec and Belak 2022).

To assist the transition and mitigate the risks highlighted, in addition to the above directives, many sustainability-related standards and guidelines (hereinafter: reporting guidelines) with different disclosure preferences and depths have been published (Makarenko and Makarenko 2023). This paper includes three of these guidelines because their strengths can be found in different segments of core importance in the banking sector. One group of the documents studied the most frequently are the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) Standards, due primarily to the in-depth elaboration of the three (economic, environmental, and social) dimensions and the versatile applicability for a wide range of companies (Ferreira Quilice et al. 2018). In 2013, the GRI G4 Financial Services Sector Disclosures (hereinafter, this concept will be abbreviated as GRI) was published to guide financial institutions in preparing their sustainability reports by introducing a set of sector-relevant key performance indicators (KPIs). This reporting guideline was based on the general GRI disclosure criteria set supplemented by new, sector-specific aspects (product portfolio, audit, active ownership) that were highly relevant for the banks, giving a total of 49 aspects (Global Reporting Initiative 2013). For a slightly different perspective, the Alliance for Corporate Transparency (hereinafter: ACT) presented research findings on 1000 companies following the NFRD regulations. The ACT is based on 16 main aspects to enhance companies’ compliance with the recent sustainability endeavor (Alliance for Corporate Transparency 2019). Unlike the GRI, which is considered a deep methodology description, the ACT document is focused instead on the research results, complemented by a brief outline of how the data were gathered. Due to this complex presentation, its implementation in banks’ reporting schemes can be easily performed with simultaneous visualization, for which the ACT document serves as a practical tool. Another guideline supporting the use of a detailed list and their itemized exposition during the preparation of company sustainability reports is the ISO 26000:2010 (hereinafter: ISO) standard (International Standard 2010). In addition to giving instructions on assessing operations even on a small scale, the ISO standard is considered a set of recommendations rather than mandatory guidance; thereby, its strict implementation is sporadic (Licandro et al. 2019). Nevertheless, the 37 aspects it presents are well associated with companies from any sector, including others from the banking sector, by assessing the whole supply chain and the range of stakeholders.

Based on the high level of recognition and a strong correlation with the NFRD and CSRD regulations, bank compliance with the GRI Standard is widely assessed in the literature; however, with scoring procedures using various methods (Smit and van Zyl 2016; Masud et al. 2018; Doğan and Kevser 2021). Along with its general acceptance and the existence of bank-specific guidelines tailored for the thorough evaluation of members in the financial sector, the representation of scoring by GRI guidelines in the literature highly outnumbers that performed by the ACT and ISO guidelines. Unlike the GRI G4 Financial Services Sector Disclosures and ISO 26000:2010, the ACT guideline assigns a scoring table to the assessment, consisting of a three-level scale referring to the thorough specification (2), identification (1), and absence (0) of aspect demonstration (Alliance for Corporate Transparency 2019). It enables the concerned companies to assess which aspects they need to address and—by proper interpretation—allows a self-evaluation that points to the strengths and weaknesses of their reporting practices.

Based on this previous work, from the researchers’ and investors’ points of view, companies’ sustainability reporting practices can be easily monitored by assessing the information presented in these documents. By studying compliance with regulations and standards, content analysis is a frequently used method. In several instances, scoring (numerical rating) is applied to determine the presence and quality of disclosure in sustainability reports (Roca and Searcy 2012; Şahin et al. 2016). Specific software (e.g., Leximancer) is also available to analyze and extract the content material (Jayarathna et al. 2022). Besides these methods, other approaches, such as expert opinion assessment and combined research methodologies, are also in use (Guthrie and Abeysekera 2006; Leszczynska 2012). As the spectrum of procedures and the diversity in different sustainability reports are broad, exclusive, universally efficient solutions for content analysis cannot be set since different text analysis techniques offer different conclusions (Aureli 2017). However, if timespan and labor intensity are not considered, manual analysis after thorough search and reading serves reliable outcomes (Ananzeh et al. 2023).

Across the member states of the European Union, differences in disclosure quality usually do not arise from the nature of the text analysis used. Still, they are consequences of actual variation in the companies’ operation (Rezaee et al. 2023). Especially in countries in the eastern region of Europe, the economic transition is burdened by difficulties of various natures (Gyura 2020). For instance, from the Hungarian perspective, it can be highlighted that financial institutions are actively developing their corporate strategies, sometimes at the expense of their ESG-related plan of action, which, on the macro scale, delays or hinders the completion of the UN SDGs (Desalegn et al. 2022). Therefore, as guidance for banks in Hungary or countries with similar challenges, relying on EU directives and any of the guidelines above could have a leading role in closing up. It was reported earlier that following global reporting guidelines enhances market value (Gerged et al. 2023), while it was also emphasized that adopting GRI standards results in better economic performance and reputation enhancement for institutions (Michelon et al. 2015). Knowing these findings, the Hungarian banks have already taken the initial significant steps: the proportion of reporting banks has been increasing, while most institutions prepare their sustainability-related reports by the GRI standards (Tamásné Vőneki and Lamanda 2020). In Hungary, the reporting improvement is widely supported by the Central Bank of Hungary (MNB), which supervises the green transition of the banking sector by providing technical guidance, initiating sustainability-related programs, and launching green financial instruments, along with an active attitude formation for the population (Boros et al. 2023).

Regarding the reporting practices of banks, all the KPIs addressed are in association with the core findings of UN SDGs; thereby, their representation in the periodic reports is becoming uniformly desired, along with a progressive improvement in reporting quality (Darnall et al. 2022; Delgado-Ceballos et al. 2023). Added, restricted or shallow ESG activities of banks could have severe adverse effects: it was previously revealed that there exists a strong positive correlation between the institutions’ sustainability reporting level and their economic performance, due mainly to the higher trust induced in the customers (Carnevale and Mazzuca 2014; Buallay 2019; Nizam et al. 2019). As the expectations and interests promote the publication of an increasing range of sustainability aspects (Wen et al. 2022), the preparedness and versatility of banks can be well monitored with a disclosure level comparison, including the three different guidelines. Moreover, such comparisons between the top European and Hungarian banks are still lacking, so the relative performances and differences have not yet been recontextualized.

As we have seen, a rapidly increasing knowledge base offers a convenient way to apply the various KPI systems to evaluate the performance of different states. We have set up a system consisting of three hypotheses by which we will be able to determine how these reporting systems can be used to evaluate the performance of various countries and analyze the similarities of these systems. We have applied the average of the analyzed European banks as benchmarks, and we have chosen Hungary—this small, open economy characterized by a rather heterogeneous banking sector—as a “test state” for comparison. We hypothesized that (i) there are significant differences in general compliance with reporting guidelines between the two bank groups (European and Hungarian), and (ii) there are also significant differences in compliance between the bank groups regarding disclosure aspects. As any or more of the three guidelines are considered by banks when compiling their reports, (iii) significant correlations were hypothesized in the disclosure compliance (scores) for the aspects between the European and Hungarian institutions within the GRI reporting guideline.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. General Compliance with Reporting Guidelines

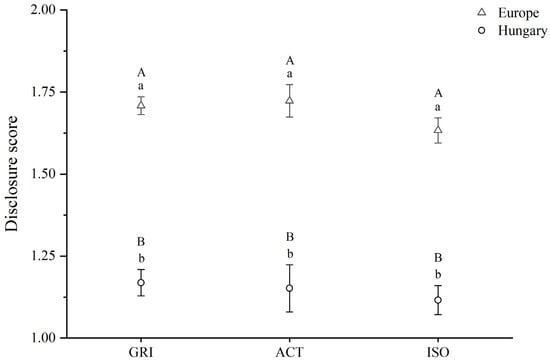

The preliminary assessment results on the overall compliance of the bank groups to the different reporting guidelines are shown in Figure 1. As presented, in the first place, significant (p < 0.05) differences were not indicated in the disclosure compliance among the three guidelines for the European and Hungarian banks. In the order of compliance, minor differences were found between the two groups: scores decreased in the order ACT > GRI > ISO for the European and in the order GRI > ACT > ISO for the Hungarian institutions.

Figure 1.

Disclosure score values of bank groups for aspects according to the three reporting guidelines (mean ± SE; n = 102). Notation: capital letters indicate significant (p < 0.05) differences in disclosure level among reporting guidelines within the selected bank group; small letters indicate significant differences in disclosure level for the chosen guideline between the bank groups.

In contrast, when comparing the two bank groups, significant differences were reported between the disclosure levels of the European and Hungarian institutions, with the European institutions having higher values in each guideline. The difference in mean scores was highest for ACT (0.57), followed by GRI (0.54), and lowest for ISO (0.52).

The European Union banks focus not only on reporting on the aspects in a tightly considered manner but rather on detailing several other issues connected more or less directly to the issue. However, Mio and Venturelli (2013) evidenced that differences in general compliance existed between the states within the European Union, interpreting the comparison results as not as uniform as presented here. Ersoy et al. (2022) found that many potential reasons for the differences in economic opportunities—and thus indirectly in allocating capacities for issues such as broadening the disclosure spectrum—are size- and revenue-based. From the reverse perspective, ESG performance was found to have various effects on the bank value. Azmi et al. (2021) drew a weak relationship between ESG operations and the institute value, while Di Tommaso and Thornton (2020) found a positive influence of ESG scores on the banks’ value. In their paper, Carnini Pulino et al. (2022) demonstrated a positive correlation between disclosures in the three ESG pillars and firm performance. Further, Andrieș and Sprincean (2023) emphasized that positive consequences of ESG activities manifest themselves mainly in large banks from economically advanced countries, with the rest having an imbalance between ESG efforts taken and the benefits yielded, which could indirectly be a reason for the relatively lower scores of the Hungarian banks.

As another proof of the importance of feedback mechanisms, according to Carnevale and Mazzuca (2014), investors set a high value on banks that disclose additional aspects compared to the ones specified in the reporting guideline taken as a basis. Considering this, along with the results presented here, the European banks were proven to be more versatile and favor the preferences of investors more than the Hungarian banks. However, the high degree of similarity in aspects among the reporting guidelines resulted in cross-compliance, which seems to mask the actual differences in such aspect-pooled analyses. This does not mean that the European banks’ reporting compliance covers all the major areas that need to be addressed in light of climate and carbon-related goals: the mean disclosure score values presented here remain below 1.75 for each guideline. This latter finding is in accordance with the observation of Friedrich et al. (2023), who studied banks’ compliance with the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures and stated that European banks usually fail to elaborate bank-specific aspects appropriately, indicating space for development in future reports. However, if subsequent ESG/sustainability reports of banks are considered, recent challenges such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the energy crises gave diverse impulses to the ESG performance of institutions, as observed by Li et al. (2022) and Al Amosh and Khatib (2023). It means that, among others, scenarios for the future that are practical to be included in reports are burdened with uncertainty, the degree of which can be mitigated with a good chance only by resilient companies having an extensive ESG approach covering a progressively increasing number of aspects (Dudás and Naffa 2021; Chiaramonte et al. 2022; Cardillo et al. 2023).

3.2. Compliance with the Aspects of Guidelines

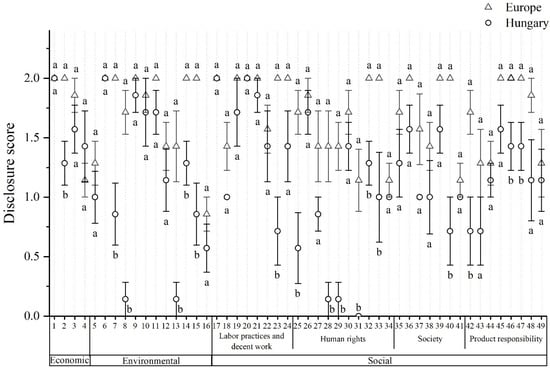

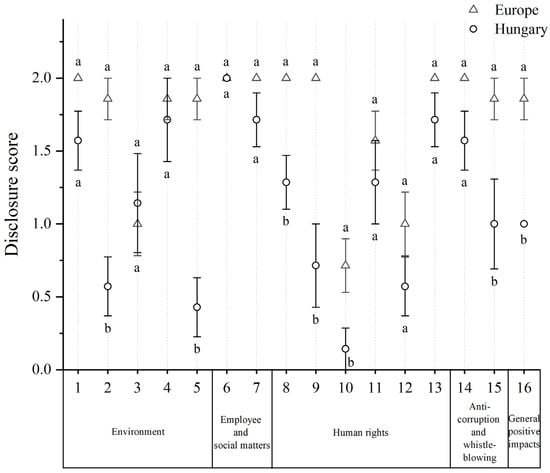

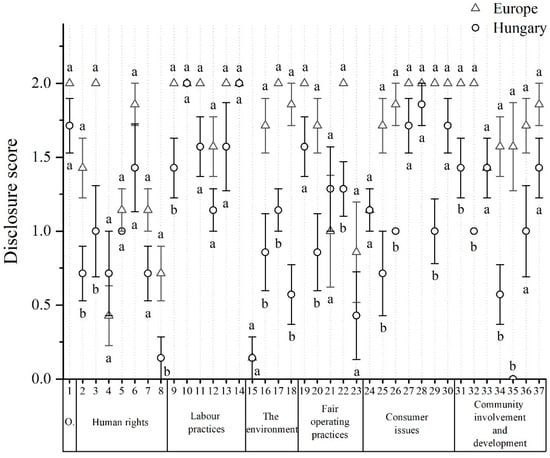

The detailed analyses performed by reporting guidelines resulted in significant differences for each guideline. The results are presented in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4, while the interpretation of the numbers assigned to aspects is shown in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Disclosure score values of bank groups for aspects according to GRI G4 Financial Services Sector Disclosures categories and sub-categories (mean ± SE; n = 7). Notation: letters above and below the error bars or directly next to the mean values indicate significant (p < 0.05) differences between bank groups within the selected aspect. For the interpretation of aspects, see Table 1.

Figure 3.

Disclosure score values of bank groups for aspects according to Alliance for Corporate Transparency (ACT) categories (mean ± SE; n = 7). Notation: letters above and below the error bars or directly next to the mean values indicate significant (p < 0.05) differences between bank groups within the selected aspect. For the interpretation of aspects, see Table 1.

Figure 4.

Disclosure score values of bank groups for aspects according to ISO 26000:2010 core subjects (mean ± SE; n = 7). Notation: letters above and below the error bars or directly next to the mean values indicate significant (p < 0.05) differences between bank groups within the selected aspect; O. = organizational governance. For the interpretation of aspects, see Table 1.

In assessing the disclosure compliance with the GRI guideline, significant differences were indicated between the two bank groups in 18 out of the 49 studied aspects (Figure 2). It was found that differences were the most significant in the aspects of biodiversity (Nr. 8, difference: 1.57), transport (Nr. 13, 1.29), supplier assessment for labor practices (Nr. 23, 1.29), child labor (Nr. 28, 1.29), forced and compulsory work (Nr. 29, 1.29), supplier assessment for impacts on society (Nr. 40, 1.29), water (Nr. 7, 1.14), supplier environmental assessment (Nr. 15, 1.14), investment (Nr. 25, 1.14), and indigenous rights (Nr. 31, 1.14); all cases favored European institutions. There were 22 aspects in which all the European banks received the highest possible score. In comparison, that was given to all the Hungarian banks in 4 aspects of economic performance (1), energy (6), employment (17), and training and education (20). In one aspect (Nr. 4, procurement practices), the Hungarian institutions performed insignificantly better, with a mean score that was 0.28 higher.

The study of compliance with the ACT guideline resulted in significant differences for 7 out of the total number of 16 aspects, with the European banks receiving the higher scores in each case (Figure 3). The difference in mean scores between the two groups was highest in the aspect of biodiversity and ecosystem conservation (Nr. 5, 1.43), followed by the use of natural resources (Nr. 2, 1.29), and human rights in supply chains (Nr. 9, 1.29). The European institutions had the highest possible score in seven aspects, while the Hungarian ones in one aspect (employees and workforce, Nr. 6). Interestingly, the mean score for pollution discharges (Nr. 3) was higher for the Hungarian than for the European banks.

For the ISO standard, a significant difference between the bank groups was detected in 16 out of the 37 aspects, all higher for the European banks (Figure 4). The difference in mean scores was the most significant for wealth and income creation (Nr. 35, 1.57), followed by protection of the environment, biodiversity, and restoration of natural habitats (Nr. 18, 1.29), human rights risk situations (Nr. 3, 1.0), protecting consumers’ health and safety (Nr. 25, 1.0), access to essential services (Nr. 29, 1.0), education and culture (Nr. 32, 1.0), and technology development and access (Nr. 34, 1.0). The European institutions received the highest possible score in 16 aspects, and the Hungarian institutions in 2 aspects (Nr. 10: employment and employment relationships; Nr. 14: human development and training in the workplace). In the aspects of avoidance of complicity (Nr. 4) and fair competition (Nr. 21), the Hungarian institutions performed better, with mean scores that were 0.29 higher.

Among the reporting guidelines, most of the papers put efforts into GRI compliance evaluations. Focusing on the progress of the ESG reporting of French firms, Chauvey et al. (2015) observed an improvement in the role of such disclosures; however, the information level in some aspects remained poor. Menicucci and Paolucci (2022) demonstrated in the Italian banking platform that compliance with different aspects of the ESG pillars had various effects on the performance of banks, with successful waste and emission reduction triggering financial indicators and higher product responsibility decreasing accounting performance. Moreover, Smit and van Zyl (2016) highlighted the shortcomings of non-European banks, naming the social segment as one with much space for development. This comparative paper did not find any salient lags in the major aspect categories within any bank group; thus, a more comprehensive analysis is needed to reveal the differences on a smaller scale.

Considering other disclosure analysis methods, Nosratabadi et al. (2020) studied the sustainability of the business model of 16 European banks from 8 countries, including Hungary, from each region of the continent. Based on the self-assessment performed by bank managers and employees, the authors found that in terms of sustainability, the included Hungarian institutions outperformed, among others, the British and French banks. These findings cannot directly be associated with the sustainability reporting performance of the banks; however, one can evaluate another perspective from the employees’ point of view. Even though the results in our paper do not confirm the outcomes presented by Nosratabadi et al. (2020), in individual cases and certain aspects, better-performing Hungarian institutions can have higher scores than those from worse-performing European banks when contrasting only one or two banks from a different origin. Cosma et al. (2020) performed a content analysis on the non-financial reports of European banks to evaluate their disclosure compliance with the 17 UN SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals). Different from our findings, the authors found by the country-wise comparison that the Hungarian banks reported on 11 out of the 17 SDGs, attaining a notable fifth place for the country among the 22 studied states. As another research with high relevancy, Tamásné Vőneki and Lamanda (2020) performed a content analysis on the ESG-related materials of nine Hungarian banks published for 2019, adopting a set of relevant questions targeting all the major fields of sustainability issues. Similar to the findings of our paper, the authors found low overall disclosure performance for the institutions, which increased slightly only when the publications of the parent banks were considered as they were made by the Hungarian subsidiary. Having a vital role in giving context to more in-depth future reporting, Tamásné Vőneki and Lamanda (2020) emphasized the implementation of ESG frameworks, which is still in the development stage for many Hungarian banks. This latter finding was also confirmed during the preparations of this paper, identifying institutions that did not present such documents.

3.3. Correlation in Compliance between the Bank Groups

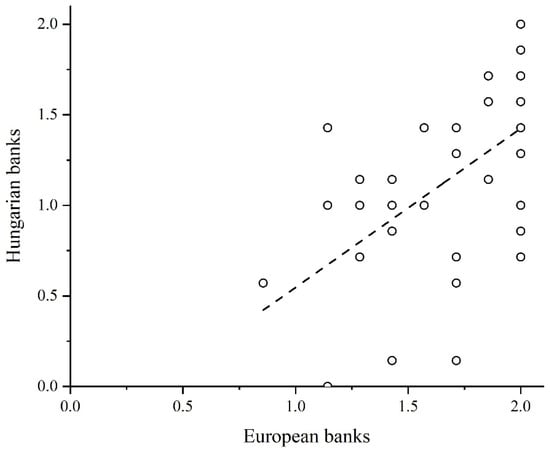

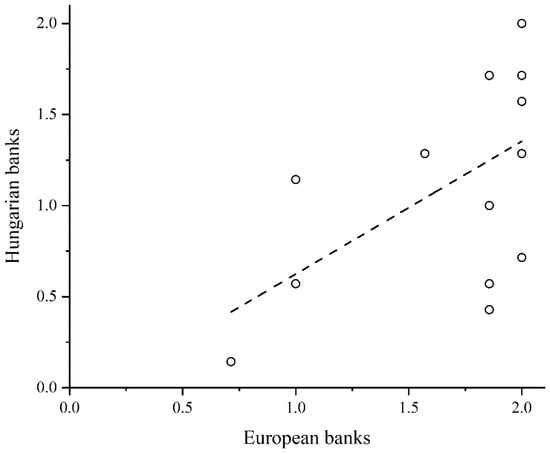

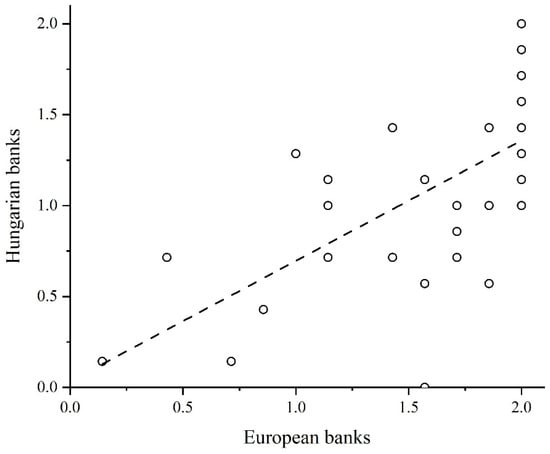

An analysis was performed to determine if there were any significant differences in compliance with the aspects of the two bank groups within each reporting guideline. In other words, it was investigated whether the high disclosure score values for the European banks were paired with those or the opposite scores for the Hungarian institutions. The results showed significant differences in the cases of all three studied guidelines, indicating a significant positive correlation by reporting on the disclosure aspects between the Hungarian and European banking institutions (Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7).

Figure 5.

Correlation between the disclosure score values of the bank groups for aspects according to GRI (n = 49, r = 0.5456, F = 19.9239, p < 0.001).

Figure 6.

Correlation between the disclosure score values of the bank groups for aspects according to ACT (n = 16, r = 0.56563, F = 6.5864, p = 0.022).

Figure 7.

Correlation between the disclosure score values of the bank groups for aspects according to ISO (n = 37, r = 0.6374, F = 23.9488, p < 0.001).

Studies evaluating the compliance of the same institution with different disclosure guidelines are scarce. When assessing compliance in a similar framework, Helfaya and Whittington (2019) studied the disclosure quality of companies through seven environmental measures and found a significant correlation between them based on the fact that all the measures focused on assessing primarily environmental aspects. Likewise, a high degree of overlapping in the disclosure topics was found in this paper, which explains the similarity in trends among the three reporting guidelines. Bruno and Lagasio (2021) reported that large European banks that profoundly adopt comprehensive reporting guidelines could be considered best practice realizers, namely catalyst exemplars for institutions that are behind in the transition progress. The results here, with significant positive relationships between the European and Hungarian banks, confirmed this previously described mechanism. Further, Ahmad et al. (2023) concluded that smaller firms cannot invest as much in ESG reporting as larger ones, resulting in different reporting levels. However, this gap can be narrowed by monitoring and adopting best practices from segments requiring workforce rather than financial investments; in the case of the Hungarian banks, the authors of this paper attribute a vital role to this phenomenon, indicating the importance not only of following a designated reporting guideline but also its adaptations by leading European institutions.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Collection

To compare the front-ranked financial institutions between an economic–political union and one of its member states, ten of the most successful banks were listed in the European Union (outside of Hungary; + United Kingdom) and Hungary by their net revenue booked for 2021. In terms of the inclusion criteria in the analyses, institutions had to feature a publication (or a well-separable section within a report) dedicated directly to their ESG/sustainability performance based on the data from the year 2021; institutions having no such publications were removed from the analyses, regardless of having a position in the list of the top banks. To collect the relevant documents, the official web pages of the 20 institutions were scanned. As the bottleneck was set by the Hungarian institutions and, simultaneously, to warrant the statistically reliable comparison of the two groups with similar sample sizes, seven of the top European (Barclays plc 2022; Citigroup Inc. 2022; Deutsche Bank AG 2022; HSBC Holdings plc 2022; Intesa Sanpaolo S.p.A. 2022; Lloyds Banking Group plc 2022; Santander Bank, N.A. 2022) and seven of the top Hungarian (CIB Bank Zrt 2022; Fundamenta Lakáskassza Lakás-takarékpénztár Zrt 2022; K&H Bank Zrt 2022; Magyar Fejlesztési Bank Zrt 2022; MKB Bank Nyrt 2022; OTP Bank Nyrt 2022; Takarék Jelzálogbank Nyrt 2022) banking institutions were included in the study (Supplementary Materials Table S1).

In the reports obtained, a comprehensive conceptual content analysis was performed to assess whether these publications (the whole document for dedicated stand-alone reports and only the ESG sections for integrated reports) report or process the topics elevated in three of the most common regulative and suggestive documents (hereinafter: reporting guidelines) that guide for the European banking institutions to aid reporting on ESG/sustainability issues. To do so, the presence and elaboration of 49 issues by GRI (GRI G4 Financial Services Sector Disclosures) (Global Reporting Initiative 2013), 16 by ACT (Alliance for Corporate Transparency) (Alliance for Corporate Transparency 2019), and 37 by ISO (ISO 26000:2010) (International Standard 2010) were studied (Table 1). The search was conducted manually, applying the aspect terms in Table 1 as search words for the English language reports; their related Hungarian terms were used for Hungarian language reports. Following the methodology presented in ACT, compliance with each issue in each banking report was rated with a whole number between 0 and 2. The assignment of the scores to the disclosure characteristics was performed according to Table 2.

Table 2.

Disclosure level scores and their interpretations used in the analyses (according to the Alliance for Corporate Transparency; in italics: specification to the interpretation, used for policies, risks, and outcomes).

Table 1.

Aspects from the three reporting guidelines evaluated in the analyses.

Table 1.

Aspects from the three reporting guidelines evaluated in the analyses.

| GRI | ACT | ISO | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Economic performance | Climate change | Organizational governance |

| 2 | Market presence | Use of natural resources | Due diligence |

| 3 | Indirect economic impact | Polluting discharges | Human rights risk situations |

| 4 | Procurement practices | Waste | Avoidance of complicity |

| 5 | Materials | Biodiversity and ecosystem conservation | Resolving grievances |

| 6 | Energy | Employees and workforce | Discrimination and vulnerable groups |

| 7 | Water | Social matters | Civil and political rights |

| 8 | Biodiversity | General human rights reporting criteria | Economic, social, and cultural rights |

| 9 | Emissions | Human rights in supply chains | Fundamental principles and rights at work |

| 10 | Effluent and waste | High risk areas for civil and political rights | Employment and employment relationships |

| 11 | Products and services | Impacts on indigenous and local communities | Conditions of work and social protection |

| 12 | Compliance | Conflict resources | Social dialogue |

| 13 | Transport | Data protection | Health and safety at work |

| 14 | Overall | Anti-corruption | Human development and training in the workplace |

| 15 | Supplier environmental assessment | Whistleblowing channels | Prevention of pollution |

| 16 | Environmental grievance mechanisms | General and sectorial positive impacts by products/sources of opportunity | Sustainable resource use |

| 17 | Employment | Climate change mitigation and adaptation | |

| 18 | Labor/management relations | Protection of the environment, biodiversity, and restoration of natural habitats | |

| 19 | Occupational health and safety | Anti-corruption | |

| 20 | Training and education | Responsible political involvement | |

| 21 | Diversity and equal opportunity | Fair competition | |

| 22 | Equal remuneration for women and men | Promoting social responsibility in the value chain | |

| 23 | Supplier assessment for labor practices | Respect for property rights | |

| 24 | Labor practices grievance mechanisms | Fair marketing, factual and unbiased information and fair contractual practices | |

| 25 | Investment | Protecting consumers’ health and safety | |

| 26 | Non-discrimination | Sustainable consumption | |

| 27 | Freedom of association and collective bargaining | Consumer service, support, and complaint and dispute resolution | |

| 28 | Child labor | Consumer data protection and privacy | |

| 29 | Forced and compulsory labor | Access to essential services | |

| 30 | Security practices | Education and awareness | |

| 31 | Indigenous rights | Community involvement | |

| 32 | Assessment | Education and culture | |

| 33 | Supplier human rights assessment | Employment creation and skills development | |

| 34 | Human rights grievance mechanisms | Technology development and access | |

| 35 | Local communities | Wealth and income creation | |

| 36 | Anti-corruption | Health | |

| 37 | Public policy | Social investment | |

| 38 | Anti-competitive behavior | ||

| 39 | Compliance | ||

| 40 | Supplier assessment for impacts on society | ||

| 41 | Grievance mechanisms for impacts on society | ||

| 42 | Customer health and safety | ||

| 43 | Product and service labeling | ||

| 44 | Marketing communications | ||

| 45 | Customer privacy | ||

| 46 | Compliance | ||

| 47 | Product portfolio | ||

| 48 | Audit | ||

| 49 | Active ownership |

Sources: International Standard (2010), Global Reporting Initiative (2013), and Alliance for Corporate Transparency (2019).

4.2. Statistical Analysis

After gathering relevant data, mean ± standard error (SE) values were calculated for each (n = 102) aspect for the European and Hungarian banks to compare the overall (aspect-pooled) compliance according to the different reporting guidelines and also by aspects within each reporting guideline between the two groups. To assess the overall compliance, scores were tested for statistical significance (p < 0.05) with a t-test. Within this sub-analysis, the existence of a significant difference among the three guidelines’ disclosure scores for the selected bank group was tested using one-way ANOVA, while the detailed nature of the difference was determined by performing the Tukey HSD post hoc test. Individual t-tests were performed to assess the differences by aspects.

As direct dependency was not supposed between the reporting practices (e.g., the scope and elaborateness of aspects) of the European and Hungarian banks, the disclosure scores by aspects for the two bank groups were analyzed using a correlation coefficient (Pearson’s r) for each reporting guideline separately. Then, the significance of the correlation was tested with linear fitting and one-way ANOVA at the p < 0.05 level.

Statistical analyses and the graphical presentation of the results were performed in OriginPro, Version 2018 (Origin(Pro) 2018), and IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 28.0, IBM Corp 2021).

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Our results highlight that the system applied in various ESG-reporting guidelines is suitable for determining a coherent picture of the ESG-related performance of different states. On this basis, various benchmarking analyses can be performed. This was well proven in the case of benchmark analysis of EU and Hungary banks by the first hypothesis. The second hypothesis was proven by a significant difference between the EU and Hungarian banks in compliance with the key performance indicators of the three reporting guidelines. Most institutions structured their sustainability-related reports according to the GRI guidelines; however, differences in ACT and ISO compliance were also similar. In the aspect-level assessment, the Hungarian banks were awarded higher scores than the European ones in 4 of 49 GRI, 1 of 16 ACT, and 2 of 37 ISO aspects. In addition, to confirm the third hypothesis, a significant correlation was shown in the disclosure score values between the two bank groups for each reporting guideline, which indicated similar preferences for the studied aspects, although at different reporting levels.

These findings showed a gap between European and Hungarian banks regarding sustainability/ESG disclosure levels. In some respects, signs of the closing up from the Hungarian banks could be identified, in which designating and following specific reporting guidelines had a major role. It is worth mentioning that the authors do not believe the presented EU–Hungarian bank relation to be an individual pattern; similar manifestations are supposed in a relevant EU-paired comparison for other countries from the eastern European regions as well; therefore, these conclusions should be handled as bases for further analyses that aim to reveal potential shortcomings in bank practices at national levels. As major steps, the implementation of extensive reporting requires much effort and time, and as there appear to be distinct requirements from the European Union toward increasing the technical quantity and quality of sustainability-related disclosures, a specific increase in the disclosure scores is expected from the banks of Hungary and countries with similar perspectives to comply with the future CSRD-level reporting requirements.

Limitations and Further Research Directions

As for each analysis, this study also has some limitations to consider. First, the scoring method used to assess the disclosure compliance of banks is based on a three-level scale (from 0 to 2) (Makarenko and Makarenko 2023). It is acknowledged that several scoring systems are adopting multi-level evaluation ranges, which provide a more in-depth insight into the sustainability reporting characteristics of companies (Thomson Reuters 2017; Helfaya and Whittington 2019; Beck et al. 2021; Refinitiv 2022). However, these mainly focus on distinguishing among companies with good disclosure performance and emphasizing the less major differences after reaching a certain aspect reporting level. Considering the previous features of more extensive scoring methods, using any of them seemed not to support the main goals of this study; as low to moderate disclosure scores were presumed in several aspects for the Hungarian banks, the differences among aspects and between the two bank groups could more apparently and comparably be presented with the scoring method used.

Another point to be raised is the relatively low sample sizes of the banks analyzed. As mentioned earlier, the sustainability-related reporting practice of large companies in the European Union is progressively more regulated; however, major deficiencies exist not only in the depth of disclosure but also before, even by more elemental steps (e.g., issuance of a relevant stand-alone or integrated report). Regarding this latter factor—thus the existence of a report for a specific year—as a prerequisite, the classification by European and Hungarian banks (and keeping the statistical consistency) did not enable the inclusion of more than seven institutions in either group, as in Hungary, these criteria were fulfilled only by seven banks. Of course, more data related to sustainability/ESG issues are available on different websites and publications and in materials presented by the parent companies of these institutions. Still, including these data would distort the actual activity performed by the local bank itself. At the same time, it is also recognized that collecting all the available data from each accessible source would provide the opportunity for comparison (Michelon et al. 2015), but rather among individual institutions.

Further, it should also be highlighted that the performance of banks was assessed for only one year, 2021. Related partly to the explanations behind the selection of the sample sizes, the study’s timespan could not be extended due to data shortage. Before 2021, the presentation of sustainability/ESG information in reports was realized only by a few Hungarian banking institutions; therefore, the analyses of preceding years would have provided insufficient sample sizes. Additionally, concerned reports for the year 2022 were not published by all the studied banks until the preparation of this paper. By that time, the involvement of more recent data was not possible. Consequently, the comparative temporal progress in related reporting practices is considered the subject of future investigations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/admsci14030058/s1, Table S1: Financial institutions and reports included in the analyses (see references below).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.T. and A.B.; methodology, D.T. and Z.L.; formal analysis, D.T.; investigation, D.T.; resources, D.T.; data curation, D.T.; writing—original draft preparation, D.T., Z.L., N.A.S. and A.B.; writing—review and editing, D.T., Z.L., N.A.S. and A.B.; visualization, D.T. and N.A.S.; supervision, Z.L. and A.B.; project administration, A.B.; funding acquisition, D.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financed by the NRDI (National Research, Development and Innovation Office) Fund [grant number 138806].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors highly appreciate the contribution of Mária Farkasné Fekete throughout the manuscript preparation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Agoraki, Maria-Eleni K., Georgios P. Kouretas, and Francisco Nadal De Simone. 2023. The performance of the euro area banking system: The pandemic in perspective. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Hadiqa, Muhammad Yaqub, and Seung Hwan Lee. 2023. Environmental-, social-, and governance-related factors for business investment and sustainability: A scientometric review of global trends. Environment, Development and Sustainability 26: 2965–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Amosh, Hamzeh, and Saleh F. A. Khatib. 2023. ESG performance in the time of COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-country evidence. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 30: 39978–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alliance for Corporate Transparency. 2019. The Alliance for Corporate Transparency Research Report 2019: An Analysis of the Sustainability Reports of 1000 Companies Pursuant to the EU Non-Financial Reporting Directive. Available online: https://www.sustentia.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/2019-Research-Report-Alliance-for-Corporate-Transparency_compressed.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Ananzeh, Husam, Mohannad Obeid Al Shbail, Hamzeh Al Amosh, Saleh F. A. Khatib, and Shadi Habis Abualoush. 2023. Political connection, ownership concentration, and corporate social responsibility disclosure quality (CSRD): Empirical evidence from Jordan. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance 20: 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrieș, Alin Marius, and Nicu Sprincean. 2023. ESG performance and banks’ funding costs. Finance Research Letters 54: 103811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aureli, Selena. 2017. A comparison of content analysis usage and text mining in CSR corporate disclosure. The International Journal of Digital Accounting Research 17: 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmi, Wajahat, M. Kabir Hassan, Reza Houston, and Mohammad Sydul Karim. 2021. ESG activities and banking performance: International evidence from emerging economies. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money 70: 101277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclays plc. 2022. Barclays PLC Annual Report 2021. Available online: https://home.barclays/content/dam/home-barclays/documents/investor-relations/reports-and-events/annual-reports/2021/Barclays-PLC-Annual-Report-2021.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Beck, A. Cornelia, David Campbell, and Philip J. Shrives. 2021. Content analysis in environmental reporting research: Enrichment and rehearsal of the method in a British–German context. The British Accounting Review 42: 207–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boros, Anita, Csaba Lentner, Vitéz Nagy, and Dávid Tőzsér. 2023. Perspectives by green financial instruments—A case study in the Hungarian banking sector during COVID-19. Banks and Bank Systems 18: 116–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowski, Piotr F. 2022. Mitigating climate change and the development of green energy versus a return to fossil fuels due to the energy crisis in 2022. Energy 15: 9289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boubaker, Sabri, Nga Nguyen, Vu Quang Trinh, and Thanh Vu. 2023. Market reaction to the Russian Ukrainian war: A global analysis of the banking industry. Review of Accounting and Finance 22: 123–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadstock, David C., Kalok Chan, Louis T. W. Cheng, and Xioawei Wang. 2021. The role of ESG performance during times of financial crisis: Evidence from COVID-19 in China. Finance Research Letters 38: 101716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruno, Michelangelo, and Valentina Lagasio. 2021. An overview of the European policies on ESG in the banking sector. Sustainability 13: 12641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buallay, Amina. 2019. Is sustainability reporting (ESG) associated with performance? Evidence from the European banking sector. Management of Environmental Quality 30: 98–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardillo, Giovanni, Ennio Bendinelli, and Giuseppe Torluccio. 2023. COVID-19, ESG investing, and the resilience of more sustainable stocks: Evidence from European firms. Business Strategy and the Environment 32: 602–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnevale, Concetta, and Maria Mazzuca. 2014. Sustainability report and bank valuation: Evidence from European stock markets. Business Ethics 23: 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnini Pulino, Silvia, Mirella Ciaburri, Barbara Sveva Magnanelli, and Luigi Nasta. 2022. Does ESG disclosure influence firm performance? Sustainability 14: 7595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauvey, Jean-Noël, Sophie Giordano-Spring, Charles H. Cho, and Dennis M. Patten. 2015. The normativity and legitimacy of CSR disclosure: Evidence from France. Journal of Business Ethics 130: 789–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaramonte, Laura, Alberto Dreassi, Claudia Girardone, and Stefano Piserà. 2022. Do ESG strategies enhance bank stability during financial turmoil? Evidence from Europe. The European Journal of Finance 28: 1173–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIB Bank Zrt. 2022. A CIB Csoport 2021. évi Üzleti és vezetőségi jelentése. Available online: https://www.cib.hu/document/documents/CIB/kommunikacio/evesjelentesek/IFRS_2021_CIB-Group__HU-220325.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Citigroup Inc. 2022. 2021 Environmental, Social & Governance Report. Available online: https://www.citigroup.com/rcs/citigpa/akpublic/storage/public/Global-ESG-Report-2021.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Connelly, Brian L., S. Trevis Certo, R. Duane Ireland, and Christopher R. Reutzel. 2011. Signaling theory: A review and assessment. Journal of Management 37: 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosma, Simona, Andrea Venturelli, Paola Schwizer, and Vittorio Boscia. 2020. Sustainable development and European banks: A non-financial disclosure analysis. Sustainability 12: 6146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CSRD. 2022. Directive (EU) 2022/2464 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2022 Amending Regulation (EU) No 537/2014, Directive 2004/109/EC, Directive 2006/43/EC, and Directive 2013/34/EU, as Regards Corporate Sustainability Reporting. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32022L2464 (accessed on 27 June 2023).

- Darnall, Nicole, Hyunjung Ji, Kazuyuki Iwata, and Toshi H. Arimura. 2022. Do ESG reporting guidelines and verifications enhance firms’ information disclosure? Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 29: 1214–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deegan, Craig Michael. 2019. Legitimacy theory: Despite its enduring popularity and contribution, time is right for a necessary makeover. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 32: 2307–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Ceballos, Javier, Natalia Ortiz-De-Mandojana, Raquel Antolín-López, and Ivan Montiel. 2023. Connecting the Sustainable Development Goals to firm-level sustainability and ESG factors: The need for double materiality. BRQ Business Research Quarterly 26: 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desalegn, Goshu, Mária Fekete-Farkas, and Anita Tangl. 2022. The effect of monetary policy and private investment on green finance: Evidence from Hungary. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 15: 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsche Bank AG. 2022. Non-Financial Report 2021. Available online: https://investor-relations.db.com/files/documents/annual-reports/2022/Non-Financial_Report_2021.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Di Tommaso, Caterina, and John Thornton. 2020. ESG scores effect bank risk taking and value? Evidence from European banks. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 27: 2286–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, Tami, Anna Husmann, and Gaia Melloni. 2023. Corporate sustainability reporting in Europe: A scoping review. Accounting in Europe 20: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, Mesut, and Mustafa Kevser. 2021. Relationship between sustainability report, financial performance, and ownership structure: Research on the Turkish banking sector. Istanbul Business Research 50: 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudás, Fanni, and Helena Naffa. 2021. Do ESG metrics reflect crisis resilience of equities during the COVID-19 pandemic? Economy and Finance 8: 371–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersoy, Ersan, Beata Swiecka, Simon Grima, Ercan Özen, and Inna Romanova. 2022. The impact of ESG scores on bank market value? Evidence from the U.S. banking industry. Sustainability 14: 9527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG). 2021. Appendix 4.6: Stream A6 Assessment Report. Current Non-Financial Reporting Formats and Practices. Available online: https://www.efrag.org/Assets/Download?assetUrl=%2Fsites%2Fwebpublishing%2FSiteAssets%2FEFRAG%2520PTF-NFRS_A6_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Ferreira Quilice, Thiago, Luciana Oranges Cezarino, Marlon Fernandes Rodriguez Alves, Lara Bartocci Liboni, and Adriana Christina Ferreira Caldana. 2018. Positive and negative aspects of GRI reporting as perceived by Brazilian organizations. Environmental Quality Management 27: 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R. Edward, Sergiy D. Dmytriyev, and Robert A. Phillips. 2021. Stakeholder Theory and the Resource-Based View of the Firm. Journal of Management 47: 1757–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, Tim Jan, Patrick Velte, and Inge Wulf. 2023. Corporate climate reporting of European banks: Are these institutions compliant with climate issues? Businsess Strategy and the Environment 32: 2817–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fundamenta Lakáskassza Lakás-takarékpénztár Zrt. 2022. Fenntarthatósági jelentés 2022. Available online: https://fundamenta.hu/documents/fundamenta-zold-jelentes-2021/ (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Gerged, Ali Meftah, Rami Salem, and Eshani Beddewela. 2023. How does transparency into global sustainability initiatives influence firm value? Insights from Anglo-American countries. Business Strategy and the Environment 32: 4519–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Reporting Initiative. 2013. GRI G4 Financial Services Sector Disclosures. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/search/?query=Financial+services (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Guthrie, James, and Indra Abeysekera. 2006. Content analysis of social, environmental reporting: What is new? Journal of Human Resource Costing & Accounting 10: 114–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyura, Gábor. 2020. ESG and bank regulation: Moving with the times. Economy and Finance 7: 366–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, Ahmed Mohamed. 2023. Do business strategies and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance mitigate the likelihood of financial distress? A multiple mediation model. Heliyon 9: e17847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, Abeer, Ahmed A. Elamer, Suman Lodh, Lee Roberts, and Monomita Nandy. 2021. The future of non-financial businesses reporting: Learning from the Covid-19 pandemic. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 28: 1231–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfaya, Akrum, and Mark Whittington. 2019. Does designing environmental sustainability disclosure quality measures make a difference? Business Strategy and the Environment 28: 525–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HSBC Holdings plc. 2022. HSBC Holdings plc Annual Report and Accounts 2021. Available online: https://www.hsbc.com/-/files/hsbc/investors/hsbc-results/2021/annual/pdfs/hsbc-holdings-plc/220222-annual-report-and-accounts-2021.pdf?download=1 (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- IBM Corp. 2021. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 28.0. Armonk: IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- International Standard (ISO). 2010. ISO 26000:2010. Guidance on Social Responsibility. Available online: https://www.iso.org/iso-26000-social-responsibility.html (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Intesa Sanpaolo S.p.A. 2022. 2021 Consolidated Non-financial Statement. Available online: https://group.intesasanpaolo.com/content/dam/portalgroup/repository-documenti/sostenibilt%C3%A0/dcnf-2021/eng/DCNF_2021_EN.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Jayarathna, Chamari, Duzgun Agdas, Les Dawes, and Marc Miska. 2022. Exploring sector-specific sustainability indicators: A content analysis of sustainability reports in the logistics sector. European Business Review 34: 321–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K&H Bank Zrt. 2022. K&H Csoport fenntarthatósági jelentés 2021. Available online: https://www.kh.hu/documents/20184/490492/K%26H+Csoport+fenntarthat%C3%B3s%C3%A1gi+jelent%C3%A9s+2021.pdf/60598a8d-3bd5-c611-4a5c-8e6a8f1dc0fa?t=1650548503079 (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Khan, Habib Zaman, Sudipta Bose, Abu Taher Mollik, and Harun Harun. 2021. “Green washing” or “authentic effort”? An empirical investigation of the quality of sustainability reporting by banks. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 34: 338–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leszczynska, Agnieszka. 2012. Towards shareholders’ value: An analysis of sustainability reports. Industrial Management & Data Systems 112: 911–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licandro, Oscar Daniel, Adán Guillermo Ramírez García, Lisandro José Alvarado-Peña, Luis Alfredo Vega Osuna, and Patricia Correa. 2019. Implementation of the ISO 26000 guidelines on active participation and community development. Social Sciences 8: 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Zengfu, Liuhua Feng, Zheng Pan, and Hafiz M. Sohail. 2022. ESG performance and stock prices: Evidence from the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 9: 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewen, Bradley. 2022. Coal, green growth and crises: Exploring three European Union policy responses to regional energy transitions. Energy Research & Social Science 93: 102849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez de Silanes, Florencio, Joseph A. McCahery, and Paul C. Pudschedl. 2019. ESG Performance and Disclosure: A Cross-Country Analysis. Singapore Journal of Legal Studies 2020: 217–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyds Banking Group plc. 2022. Lloyds Banking Group ESG Report 2021. Available online: https://www.lloydsbankinggroup.com/assets/pdfs/who-we-are/responsible-business/downloads/2021-reporting/lbg-esg-report-2021-interactive-final.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Magyar Fejlesztési Bank Zrt. 2022. Fenntarthatósági jelentés 2021. Available online: https://www.mfb.hu/backend/documents/MFB_fenntarthatosagi_jelentes_2021_0102.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Makarenko, Inna, and Serhiy Makarenko. 2023. Multi-level benchmark system for sustainability reporting: EU experience for Ukraine. Accounting and Financial Control 4: 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masud, Md. Abdul Kaium, Mohammad Sharif Hossain, and Jong Dae Kim. 2018. Is green regulation effective or a failure: Comparative analysis between Bangladesh Bank (BB) Green Guidelines and Global Reporting Initiative Guidelines. Sustainability 10: 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menicucci, Elisa, and Guido Paolucci. 2022. ESG dimensions and bank performance: An empirical investigation in Italy. Corporate Governance 23: 563–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelon, Giovanna, Silvia Pilonato, and Federica Ricceri. 2015. CSR reporting practices and the quality of disclosure: An empirical analysis. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 33: 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miklaszewska, Ewa, Krzysztof Kil, and Marcin Idzik. 2021. How the COVID-19 Pandemic Affects Bank Risks and Returns: Evidence from EU Members in Central, Eastern, and Northern Europe. Risks 9: 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mio, Chiara, and Andrea Venturelli. 2013. Non-financial information about sustainable development and environmental policy in the annual reports of listed companies: Evidence from Italy and the UK. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 20: 340–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MKB Bank Nyrt. 2022. Fenntarthatósági jelentés 2021. Available online: https://www.mbhbank.hu/sw/static/file/mkb_esg_jelentes_20221116_APPROVED.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- NFRD. 2014. Directive 2014/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2014 Amending Directive 2013/34/EU as Regards Disclosure of Non-Financial and Diversity Information by Certain Large Undertakings and Groups. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32014L0095 (accessed on 27 June 2023).

- Nieto, María J., and Chryssa Papathanassiou. 2023. Financing the orderly transition to a low carbon economy in the EU: The regulatory framework for the banking channel. Journal of Banking Regulation. in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizam, Esma, Adam Ng, Ginanjar Dewandaru, Ruslan Nagayev, and Malik Abdulrahman Nkoba. 2019. The impact of social and environmental sustainability on financial performance: A global analysis of the banking sector. Journal of Multinational Financial Management 49: 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosratabadi, Saeed, Gergo Pinter, Amir Mosavi, and Sandor Semperger. 2020. Sustainable banking; Evaluation of the European business models. Sustainability 12: 2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opferkuch, Katelin, Sandra Caeiro, Roberta Salomone, and Tomás B. Ramos. 2022. Circular economy disclosure in corporate sustainability reports: The case of European companies in sustainability rankings. Sustainable Production and Consumption 32: 436–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Origin(Pro), Version 2018. 2018. Origin(Pro), Version 2018. Northampton: OriginLab Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- OTP Bank Nyrt. 2022. Fenntarthatósági jelentés 2021. Available online: https://www.otpbank.hu/static/portal/sw/file/OTP_Csoport_Fenntarthatosagi_jelentes_2021.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Primec, Andreja, and Jernej Belak. 2022. Sustainable CSR: Legal and managerial demands of the new EU legislation (CSRD) for the future corporate governance practices. Sustainability 14: 16648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refinitiv. 2022. Environmental, Social and Governance Scores from Refinitiv. Available online: https://www.refinitiv.com/content/dam/marketing/en_us/documents/methodology/refinitiv-esg-scores-methodology.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- Rezaee, Zabihollah, Saeid Homayoun, Ehsan Poursoleyman, and Nick J. Rezaee. 2023. Comparative analysis of environmental, social, and governance disclosures. Global Finance Journal 55: 100804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, Laurence Clément, and Cory Searcy. 2012. An analysis of indicators disclosed in corporate sustainability reports. Journal of Cleaner Production 20: 103–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, Zeynep, Fikret Çankaya, and Züleyha Yilmaz Soğuksu. 2016. Content analysis of sustainability reports: A practice in Turkey. Paper presented at 7th European Business Research Conference, Rome, Italy, December 15–16. [Google Scholar]

- Santander Bank, N.A. 2022. ESG Report 2021. Available online: https://www.santander.com/content/dam/santander-com/en/contenido-paginas/nuestro-compromiso/reports/doc-informe-BR-polonia-2021.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- SFDR. 2020. Regulation (EU) 2020/852 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 June 2020 on the Establishment of a Framework to Facilitate Sustainable Investment, and Amending Regulation (EU) 2019/2088. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32020R0852 (accessed on 27 June 2023).

- Smit, Anet M., and Johan van Zyl. 2016. Investigating the extent of sustainability reporting in the banking industry. Banks and Bank Systems 11: 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Söderholm, Patrik. 2020. The green economy transition: The challenges of technological change for sustainability. Sustainable Earth Reviews 3: 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takarék Jelzálogbank Nyrt. 2022. Fenntarthatósági jelentés 2021. Available online: https://bet.hu/newkibdata/128775836/TJB_ESG_jelentes_2021_pub.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Tamásné Vőneki, Zsuzsanna, and Gabriella Lamanda. 2020. Content analysis of bank disclosures related to ESG risks. Economy and Finance 7: 412–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson Reuters. 2017. Thomson Reuters ESG Scores. Available online: https://www.esade.edu/itemsweb/biblioteca/bbdd/inbbdd/archivos/Thomson_Reuters_ESG_Scores.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- Wen, Hui, Ken C. Ho, Jijun Gao, and Li Yu. 2022. The fundamental effects of ESG disclosure quality in boosting the growth of ESG investing. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money 81: 101655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Xiao-Na, Jing-Ping Li, and Chi-Wei Su. 2023. How does ESG performance affect stock returns? Empirical evidence from listed companies in China. Heliyon 9: e16320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zetzsche, Dirk A., and Linn Anker-Sørensen. 2022. Regulating sustainable finance in the dark. European Business Organization Law Review 23: 47–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).