Abstract

The present study consists of a systematic literature review, based on the PRISMA model, with the objective of analyzing the relationship between organizational support and career self-management in order to address the gaps in the existing literature. Specifically, it seeks to answer whether organizational support influences career self-management behaviors and whether the inverse also occurs. To systematize the scientific knowledge on this topic over the past 13 years (2010–2023), three databases were consulted: Web of Science, Scopus, and Core. This research resulted from the combination of the keywords “career self-management” and “organizational support: and involved the screening of 353 studies. For the systematic literature review, a total of six studies were identified that met the established eligibility criteria. The main conclusions of this study are that organizational support, in the form of perceived organizational support, human resource management practices/perception of human resource management practices, and leader–member exchanges, appears to positively influence career self-management, as well as the inverse. Such evidence can be observed through the direct and indirect relationships established between the variables. This relationship leads, for example, to workers being more satisfied with their careers while also becoming more committed to the organization. Overall, this systematic literature review provides practical implications for organizations and their workers. It is suggested that future research should explore the relationship between career self-management and organizational support, as well as other potential mediators of this relationship.

1. Introduction

In the course of the Fourth Industrial Revolution or Industry 4.0, with rapid technological advancement leading to the elimination of several jobs and changes in the skills required for many others, careers will become increasingly volatile, uncertain, ambiguous, and complex (WEF 2020; Wilhelm and Hirschi 2019). Due to growing job and career insecurity, workers must engage in self-directed career behaviors to survive in the job market (Yogalakshmi and Suganthi 2020). Simultaneously, the conception of a career has changed, and a career is now considered as a process of personal development (e.g., Brown and Lent 2021; Barroso 2016) instead of a linear path where growth occurs vertically in the hierarchy of an organization (e.g., Barroso 2016; Gerber et al. 2009).

In this context, career self-management emerges as essential for professionals, with organizational support potentially serving as a supporting mechanism in this process. Considering the reviewed literature, this study aims to analyze the relationship between organizational support and career self-management through a systematic literature review. Specifically, it seeks to answer the following questions: Does organizational support influence career self-management behaviors? Conversely, does the inverse occur? To this end, organizational support will be examined through perceived organizational support, perception of human resource management practices, and leader–member exchange. On the other hand, career self-management will be addressed through its concept or career self-management behaviors. With the systematization of scientific knowledge on this topic over the past 13 years (2010–2023), the aim is to unveil the theoretical foundations of this relationship and present its effectiveness for both organizations and individuals. In contemporary times, the need for strategies that benefit both parties is crucial. The need for this study stems from the importance of investing in scientific studies on the impact of organizational support on career self-management, and vice versa, to address the current gaps in the existing literature on this topic, as this is an emerging area of research. Thus, conducting a systematic literature review is essential to understand the state of the art on this topic. Furthermore, there is currently no systematic literature review that addresses the relationship between these two concepts.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Career Self-Management

The contemporary conception of a career is, therefore, related to current challenges, requiring resources such as career adaptability (e.g., Barroso 2016; Paradnike et al. 2016) and mechanisms for self-actualization and career self-management (Paradnike et al. 2016). According to Wilhelm and Hirschi (2019), career self-management is a process of managing personal and contextual resources through processes such as goal setting and planning, among others, that lead to positive career outcomes. On the other hand, according to authors such as Akkermans et al. (2012) and Kossek et al. (1998), career self-management concerns the proactive behavior of an individual, aiming at managing their career. Thus, although the definition of career self-management is not unanimous among various researchers, all point to its dynamic, self-directed, and proactive nature, with cognitive and behavioral components (Hirschi and Koen 2021). In order to include the aforementioned aspects, Hirschi and Koen (2021) adopt in their study the definition from Greenhaus et al. (2010, p. 12), which conceptualizes career self-management as ‘a process by which individuals develop, implement, and monitor career goals and strategies’.

In summary, it is evident that career self-management is characterized by a strong emphasis on the individual, as they take control of this entire process (Wilhelm and Hirschi 2019). Therefore, a worker should develop self-awareness regarding their career aspirations and interests as well as develop self-efficacy beliefs and engage in career planning, goal setting, networking, generating opportunities, and exploring their own career (Coetzee and Schreuder 2018; Hirschi and Koen 2021).

Jung and Takeuchi (2018) consider career self-management as one of the most influential personal resources in achieving career satisfaction, having corroborated this significant relationship with empirical evidence. Career satisfaction is directly or indirectly associated not only with individual outcomes (Jung and Takeuchi 2018), such as happiness (Pan and Zhou 2013) and subjective well-being (Joo and Lee 2017), but also with organizational outcomes (Jung and Takeuchi 2018), such as professional performance (Trivellas et al. 2015), decreased intention of individuals to leave the organization, and consequently low turnover (Chan and Mai 2015). The effect of career self-management in organizations can therefore be extremely beneficial and become an asset, both for the worker and for the organization, and how the organization handles this process is crucial (Wilhelm and Hirschi 2019). Despite its importance, the study of career self-management and organizational management practices in encouraging career self-management is incipient and therefore deserves more attention and research.

2.2. Organizational Support

In the 21st century, the topic of organizational support has gained increasing relevance (Dursun 2015), although its concept dates back to the previous century. According to organizational support theory, workers personify the organization, and, therefore, the actions of those who represent it are understood by workers as being those of the organization itself (Eisenberger et al. 2020; Ciliato et al. 2019). As a consequence, perceived organizational support is defined by the worker’s perception of the organization, ranging from the appreciation of their contributions to concern for their well-being (Eisenberger et al. 1986). Eisenberger et al. (1986) consider that worker interactions with the organization are characterized by expectations of reciprocity, invoking Blau’s social exchange theory (1964) and Gouldner’s norm of reciprocity (1960) as bases for their rationale.

According to Blau (1964), social exchanges involve actions taken by individuals with the expectation of return and typically result from other returns. This theory presupposes that positive and beneficial exchanges between the worker and the organization strengthen their relationship (Tavares 2021). Blau’s (1964) social exchange theory converges with Gouldner’s (1960) norm of reciprocity. This latter infers that workers reciprocate favorable treatment made by those who represent the organization (Settoon et al. 1996; Tavares 2021). Thus, it can be concluded that when workers feel valued and perceive favorable treatment from organizations, they also respond positively (Eisenberger et al. 2020; Kurtessis et al. 2017).

Organizational support is associated with a variety of positive outcomes for the individual and the respective organization. For example, organizational support is positively related to trust in the organization, organizational commitment (Dursun 2015; Kurtessis et al. 2017), work engagement (Kurtessis et al. 2017), performance (Ciliato et al. 2019), job satisfaction, and intention to stay in the organization (Kurtessis et al. 2017), among others. On the other hand, it is negatively related to work stress, burnout (Kurtessis et al. 2017), absenteeism (Ciliato et al. 2019), and turnover (Kurtessis et al. 2017).

In current career contexts, organizational support involves supporting the process of workers’ career self-management. This includes offering opportunities for work and career autonomy, supporting and structuring skills development, continuous training and qualification of workers, incentives for exploration and the establishment of networking and relationships, and formative and results-based evaluation across a variety of dimensions over time (Taveira 2022).

2.3. Career Self-Management and Organizational Support

Yogalakshmi and Suganthi (2020) demonstrated that perceived organizational support positively influences career self-management. Organizational support is characterized not only by general support for the employee, such as concern for their well-being (Wilhelm and Hirschi 2019), but also by the support provided for career development, including career guidance and counseling, development opportunities, mentoring programs, career workshops, career planning, and performance feedback (Baruch 1999; Wilhelm and Hirschi 2019). In this regard, it is ideal for organizations to encourage their employees to proactively manage their careers while providing support for their career development. This relationship will possibly translate into increased organizational productivity as well as improved worker well-being (Wilhelm and Hirschi 2019). For this relationship to function effectively, organizations need to provide career development support tailored to the organizational culture as well as offer personalized career opportunities, which do not necessarily imply advancement to a higher hierarchical level but rather the development of career opportunities within and between individual job functions (Wilhelm and Hirschi 2019). However, the current reality of the organizational world requires that individuals take control of their careers (Coetzee 2018), and, therefore, we should not place this responsibility solely on organizations. In the same way that organizational support influences career self-management, the inverse also occurs, as self-directed career behaviors, such as networking, help justify the provision of, for example, impartial career counseling services, which consequently reinforce these behaviors, creating a “virtuous circle” (Sturges et al. 2002). In light of the reciprocal relationship between organizational support and career self-management (Wilhelm and Hirschi 2019), it becomes evident that career management should be a joint responsibility between the worker and the organization (Orpen 1994).

3. Methods

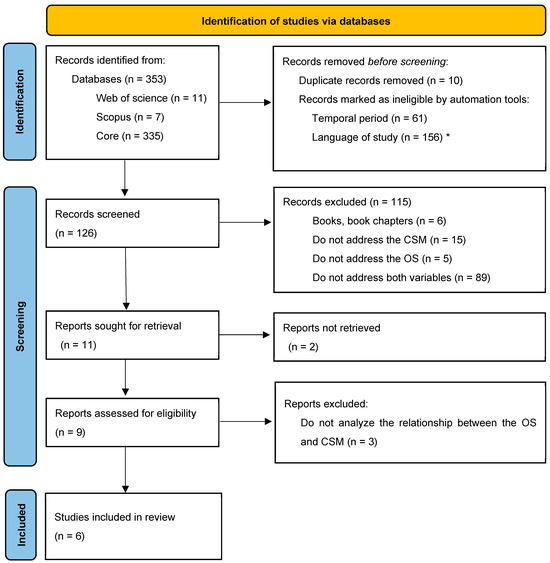

Considering the nature of the problem under study, a systematic literature review was conducted to analyze the relationship between organizational support and career self-management over the past 13 years (2010–2023). This approach allowed for an in-depth exploration of the topic under analysis through the collection, analysis, description, and interpretation of the viewpoints of various authors (Zawacki-Richter et al. 2020). This systematic review was based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) model, which consists of a checklist of twenty-seven items considered essential for transparent communication of a systematic review and a four-phase flow diagram named identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion (Selçuk 2019). This tool aims to assist researchers during the review process, with the PRISMA flow diagram used to document the search strategy, providing a clear graphical representation of the entire process. It includes details on the number of studies identified and included or excluded for review and provides an explanation for each excluded article, eligibility verification, and the final selection of articles included in the systematic literature review (Pati and Lorusso 2018).

The bibliographic search was conducted on 20 March 2023 through three databases: Web of Science, Scopus, and Core. The first two were chosen because they are reference databases in the field of psychology, a discipline that addresses the topic. The third was selected after testing various dissertation/thesis databases to address the insufficient number of articles found. This research was conducted with the aim of completing a master’s thesis in 2023 (Martins 2023).

3.1. Eligibility Criteria

The evaluation of the studies was conducted according to the following inclusion criteria: (a) studies published in English or Portuguese; (b) publications in scientific articles, dissertations, or theses; (c) studies published between 2010 and 2023; (d) studies that analyze the relationship between organizational support and career self-management. In turn, the exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) studies not in English or Portuguese; (b) books, book chapters; (c) studies published before 2010; (d) duplicate studies; (e) studies not accessible in full text; (f) studies that do not analyze the relationship between organizational support and career self-management.

3.2. Procedure

To initiate the process underlying a systematic literature review, an independent bibliographic search was conducted to gain an idea of the keywords that should be used. Concomitantly, various databases were tested. Initially, the chosen databases were Web of Science and Scopus. However, due to the insufficient number of articles, it was necessary to consult a database of dissertations or theses. After testing several databases, the choice fell on Core for being a more comprehensive database.

The bibliographic search for this systematic literature review was conducted independently by a researcher on 20 March 2023 using three databases: Web of Science, Scopus, and Core. The keywords used in the search were “career self-management” and “organizational support”, which effectively filtered the literature focused on the central theme, without the need to add others. The search identified a total of 353 studies: 11 from Web of Science, 7 from Scopus, and 335 from Core. Additionally, the following automated tools were applied: temporal period (2010–2023) and language of study (Portuguese and English). The temporal period was defined based on the publication year of one of the pioneering studies in this field (Sturges et al. 2010) and the search date cutoff (18 March 2023). By restricting the temporal period to “2010–2023”, 292 studies were selected: 9 from Web of Science, 7 from Scopus, and 276 from Core, while 61 studies were discarded. It should be noted that the Core database only included studies published up to 2021 (limit up to research date). Subsequently, the search was limited to studies in Portuguese and English, resulting in 139 studies selected: 9 from Web of Science, 7 from Scopus, and 123 from Core, with 153 studies discarded. Due to the use of automated tools, the identified studies were verified manually by the researcher to address potential gaps, leading to the exclusion of three studies that did not meet the language criteria.

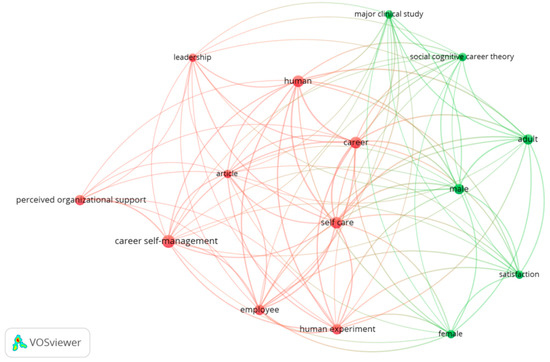

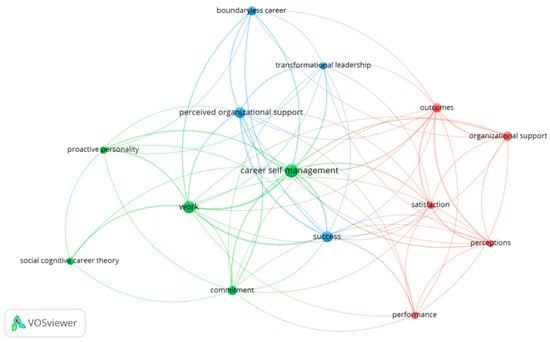

To illustrate the network of keywords used in the articles identified from the Web of Science and Scopus databases, the VOSviewer software tool (version 1.6.19) was employed. To this end, the RIS file was extracted from both databases, selecting the information related to the keywords. Subsequently, the VOSviewer tool was used, where the data from the RIS file were processed, and a map was created based on bibliographic data, specifically focusing on the occurrence of keywords. It should be noted that this was not possible for the Core database. The network analysis of the keywords used in the articles identified by the Scopus and Web of Science databases can be observed in Figure 1 and Figure 2, respectively. In Figure 1, the bibliometric analysis presents two groups of keywords: (1) career self-management, career, self-care, human, employee, human experiment, perceived organizational support, leadership, article; (2) adult, male, female, major clinical study, social cognitive career theory and satisfaction. In Figure 2, the bibliometric analysis presents three groups of keywords: (1) career self-management, work, commitment, proactive personality, social cognitive career theory; (2) organizational support, outcomes, perceptions, satisfaction, performance; (3) success, perceived organizational support, boundaryless career and transformational leadership. The bibliometric analysis conducted using VOSviewer aimed to explore the occurrence of keywords in the initial phase of the research, serving as an exploratory step in this systematic literature review.

Figure 1.

Keyword network of studies identified by Scopus, generated by VOSviewer.

Figure 2.

Keyword network of studies identified by the Web of Science, generated by VOSviewer.

After identifying the studies, 10 duplicate studies were discarded, leaving a total of 126 studies for title and abstract analysis. The titles and abstracts of the studies were then reviewed, and based on the exclusion and inclusion criteria, 11 studies were identified as relevant and 115 were discarded (6 were books or book chapters; 15 did not address career self-management; 5 did not address organizational support; and 89 did not address both variables of interest). The relevant articles were subsequently read and analyzed to assess their eligibility, resulting in six studies being selected and five studies being discarded (three did not analyze the relationship between organizational support and career self-management; two were not accessible in full text).

Throughout the entire process of selecting and analyzing the articles, the aforementioned inclusion and exclusion criteria were consistently checked. The selection process can be observed through the PRISMA flow diagram below (Figure 3). The process was monitored using Microsoft Excel and reviewed by two independent researchers. Any disagreements were resolved through discussions between the two researchers, ensuring that all eligibility criteria were met. Microsoft Excel was a significant facilitator in this process, as it was used for two distinct purposes: firstly, to document the study selection process, and secondly, to extract data from the studies included in this systematic literature review. The data from the studies included in this review were extracted into Microsoft Excel, highlighting their fundamental characteristics such as year of publication, authors, title, hypotheses, methodology, study design, sample population and eligibility criteria, sample size, gender, age, education level, tenure in the organization, main results, and limitations.

Figure 3.

PRISMA flow diagram. Note. Use of the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram (Page et al. 2021); CSM = career self-management; OS = organizational support. * 3 studies were removed based on researcher verification.

The quality and risk of bias of the studies were assessed using the Appraisal tool for Cross-Sectional Studies (AXIS) (Downes et al. 2016). This tool contains 20 items and evaluates aspects such as (1) clarity of study objectives, (2) appropriateness of study design, and (3) sample size justification, among others. The Appraisal tool for Cross-Sectional Studies (AXIS) developed by Downes et al. (2016) is accompanied by an informative guide and was selected solely because its question typology is aligned with all studies included in this review.

Based on an assessment of their quality and relevance, the data were interpreted, and comparisons were made. That is, whenever a result referred to the relationship between organizational support, in the form of perceived organizational support, perception of human resource management practices, and leader–member exchange, and career self-management, in the form of specific career self-management behaviors or the concept itself, it was included. The information from the studies selected for this systematic literature review was synthesized into three tables. It should be noted that both positive and negative results from the studies were presented, as publishing these aspects enhances understanding of the effectiveness of organizational support in career self-management and vice versa, as well as their potential limitations. Upon completing this systematic literature review, its quality was assessed using the PRISMA 2020 checklist (Page et al. 2021).

4. Results

4.1. Study Characteristics

The conducted research identified a total of six studies being eligible for inclusion in the systematic literature review. All studies met the proposed inclusion criteria, focusing on the analysis of the relationship between career self-management and organizational support. The studies included for analysis consisted of four articles (66.7%) and two master’s theses (33.3%). Considering the publication year of the six studies, with the exception of one study, all others were published between 2016 and 2022 (83.3%), indicating a growing interest in this topic among researchers in recent years. Regarding methodology, all studies opted to use questionnaires (100%). However, four studies administered them at a single time point (66.7%), while two studies administered different questionnaires at two different time points (33.3%).

The six included studies covered samples of workers from various organizations located in Portugal (33.3%), the United Kingdom (16.7%), Japan (16.7%), India (16.7%), and China (16.7%). Samples ranged from 257 (minimum) to 664 (maximum) workers. Concerning participants, in the majority of studies (66.7%), the female sample exceeded the male sample. Regarding participants’ age and tenure in the organization, studies differ or fail to provide this information, making it impossible to accurately analyze their means and standard deviations. Regarding participants’ educational background, although the study by Polanska (2016) does not make any reference to it, looking at the remaining studies, it is possible to deduce that the majority of participants attended higher education.

On average, the studies included in this systematic literature review identified approximately 2.67 limitations, with the most reported being the method used (100%) and the selection of participant samples (83.3%). In Table 1, the main characteristics of the studies are represented, including the authors, year and type of publication, method used, and participant sample (population, size (N), gender of participants (N and/or %), age, education level, and tenure in the organization).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included in the systematic literature review.

4.2. Instruments

Regarding the studies included in this systematic literature review, it is important to understand the instruments used to evaluate the variables, particularly the variables of interest: career self-management/career self-management behaviors (CSM/CSMBs), human resource management practices/perception of human resource management practices (HRMPs/PHRMP), perceived organizational support (POS), and leader–member exchange (LMX).

The six studies included in this systematic literature review evaluated CSM/CSMBs. Three of the studies (50%) selected items from the instrument by Sturges et al. (2000, 2002, 2005), two studies (33.3%) opted for the Career Aspirations Scale by Tharenou and Terry (1998), and only one study (16.7%) preferred items from the Career Self-Management Scale by Ma and Cheng (2010).

Regarding the instruments used to evaluate HRMPs/PHRMP, two of the four studies that assessed this variable (50%) used a customized measure with items representing HRMPs, one study (25%) opted for items from the High-Performance Work Systems (HPWS) developed by Takeuchi et al. (2007), while another (25%) preferred the Developmental HR Practices Scale developed by Kuvaas (2008). In turn, all four studies that evaluated POS (100%) used items from Eisenberger et al. (1986, 2001, 2020). The only study that evaluated LMX used the seven-item LMX scale (Liden and Graen 1980; Scandura and Graen 1984).

Table 2 presents the instruments used to evaluate the variables in the six studies, specifically the aforementioned variables of interest.

Table 2.

Instruments used in the studies included in the systematic literature review to assess their respective variables.

Table 3 below presents the main results obtained from the six studies included in this systematic literature review.

Table 3.

Principal findings of the studies included in the systematic literature review.

4.3. Studies on Career Self-Management and Organizational Support

The relationship between organizational support and career self-management was the focus of investigation in the six studies included in this systematic literature review. Organizational support was mentioned in the various studies through the terms perceived organizational support (POS) and/or human resource management practices/perception of human resource management practices (HRMPs/PHRMP) and/or leader–member exchanges (LMX), while career self-management was approached through the concept/behaviors of career self-management (CSM/CSMBs).

4.3.1. Career Self-Management and Human Resource Management Practices

The relationship between human resource management practices and career self-management was explored in four of the six studies analyzed. The results of the three studies that examined the direct relationship between the variables indicated that HRMPs were positively related to CSM, suggesting that the adoption of human resource management practices by organizations promotes employees’ engagement in career self-management behaviors (Liu et al. 2022; Polanska 2016; Varela 2018).

Regarding indirect relationships, two studies observed the mediating effect of different variables in the relationship between PHRMP and CSM. Varela (2018) demonstrated that the relationship between PHRMP and CSM can be mediated either by leaders’ emotional regulation or by work engagement. These results suggest that workers’ positive PHRMP leads to higher levels of work engagement, which promotes the adoption of CSM. Similarly, HRMPs influence leaders’ emotional regulation; consequently, emotionally intelligent leaders project a ‘role model’ image, exerting a positive influence on workers, resulting in their engagement in CSM (Varela 2018). In line with this idea, Liu et al. (2022) found that the relationship between HRMPs and CSM can be partially mediated by transformational leadership. These results suggest that HRMPs influence transformational leadership; consequently, the latter has a significant influence on workers and may contribute to the adoption of CSM (Liu et al. 2022).

One study evaluated the mediating effect of CSM on the relationship between HRMPs and other variables. Polanska (2016) revealed the mediating effect of CSM in the relationship between HRMPs and organizational commitment. The results suggest that the adoption of HRMPs by organizations promotes workers’ engagement in CSM, which in turn enhances workers’ commitment to the organization. According to Polanska (2016), CSM accounted for 20% of the effect of HRMPs on organizational commitment. This author also demonstrated that the relationship between HRMPs and perceived employability was partially mediated by CSMBs. The results suggest that the adoption of HRMPs by organizations encourages employees’ engagement in CSM; consequently, these behaviors lead to gains that promote employability and subsequently the perceived employability of workers. According to Polanska (2016), CSMBs accounted for 28% of the effect of HRMPs on perceived employability.

Another study investigated the mediating effect of HRMPs on the relationship between CSM and career satisfaction in young and middle-aged workers (Jung and Takeuchi 2018). The results determined that the relationship between CSM and career satisfaction in young workers was strengthened when there were high levels of PHRMP. On the other hand, the relationship between CSM and career satisfaction in middle-aged workers was strengthened when there were low levels of PHRMP. Regarding direct relationships, researchers demonstrated that CSM and HRMPs were positively related to career satisfaction (Jung and Takeuchi 2018).

4.3.2. Career Self-Management and Perceived Organizational Support

The relationship between perceived organizational support and career self-management was explored in four of the six articles analyzed. However, only two studies addressed the direct relationship between these two variables.

Yogalakshmi and Suganthi (2020) concluded that POS was positively related to CSM. In other words, when workers perceive support from the organization, they tend to engage in CSMBs. In contrast to the findings of Yogalakshmi and Suganthi (2020), Sturges et al. (2010) did not find evidence that POS was positively related to CSMBs oriented to career advancement within the organization (networking and visibility behaviors). However, the same researchers found that POS was negatively related to CSMBs oriented to career advancement outside the organization (mobility behaviors).

Two studies investigated POS as a moderating variable. Liu et al. (2022) observed that the mediating effect of transformational leadership in the relationship between HRMPs and CSM, highlighted earlier, can be moderated by POS, with the strongest effect observed for higher levels of POS. In other words, for workers who perceive higher levels of POS, the effect of transformational leadership can function as a signal of support from the organization, resulting in engagement in CSM. Similarly, Sturges et al. (2010) found evidence of POS as a moderating variable but in the relationship between CSM and other variables (gender and locus of control). Sturges et al. (2010) demonstrated that the relationship between locus of control and CSM can be moderated by POS, where individuals with an internal locus of control were more favorable to networking and visibility behaviors at higher levels of POS compared to those with an external locus of control. On the other hand, the relationship between gender and CSM was moderated by POS in the opposite direction to that expected by the researchers; that is, women were more favorable than men to engage in networking and visibility behaviors at lower levels of POS (Sturges et al. 2010). It should be noted that no significant evidence was found for interactions between locus of control * POS and gender * POS regarding mobility-directed behaviors (Sturges et al. 2010).

One study assessed the mediating effect of CSM and concluded that it partially mediates the relationship between POS and affective commitment (Yogalakshmi and Suganthi 2020). The results indicate that, through social exchange theory and the norm of reciprocity, the perception of organizational support motivates employees to engage in CSM, which in turn enhances the opportunity to receive support from the organization, leading to increased affective commitment of the employee towards the organization (Yogalakshmi and Suganthi 2020).

Another study investigated the mediating effect of POS on the relationship between CSM and career satisfaction in young workers and middle-aged workers (Jung and Takeuchi 2018). The results determined that the relationship between CSM and career satisfaction in young workers was strengthened when there were high levels of POS. On the other hand, the relationship between CSM and career satisfaction in middle-aged workers was strengthened when there were low levels of POS. In terms of direct relationships, researchers demonstrated that CSM and POS were positively related to career satisfaction (Jung and Takeuchi 2018).

4.3.3. Career Self-Management and Leader–Member Exchange

The relationship between leader–member exchange and career self-management was explored in only one of the six articles analyzed.

Sturges et al. (2010) concluded that LMX was positively related to CSM oriented towards career advancement within the organization, specifically regarding visibility behaviors but not regarding networking behaviors and negatively related to CSM oriented towards career advancement outside the organization (mobility-directed behaviors).

The same study investigated LMX as a moderating variable. Sturges et al. (2010) found evidence of LMX as a moderating variable in the relationship between CSM and other variables (gender and locus of control). The authors demonstrated that the relationship between gender and CSM can be moderated by LMX, with women being more favorable than men to engage in networking behaviors at higher levels of LMX; however, no evidence was found regarding visibility behaviors. On the other hand, the relationship between locus of control and CSM appeared to be moderated by LMX in the opposite direction expected, with individuals with an internal locus of control being more inclined than those with an external locus of control to engage in networking behaviors at lower levels of LMX (Sturges et al. 2010). It should be noted that no evidence was found for interactions between gender * LMX and locus of control * LMX regarding mobility-directed behaviors (Sturges et al. 2010).

5. Discussion

The present review aims to analyze the relationship between career self-management and organizational support and to synthesize the information available over the past 13 years. It should be noted that only six studies were found for analysis, making it difficult to draw generalizations based on such limited evidence. However, the main conclusions of this study are that organizational support, in the form of perceived organizational support, human resource management practices/perception of human resource management practices, and leader–member exchange, appears to positively influence career self-management, as well as the inverse. Such evidence can be observed through the direct and indirect relationships established between the variables. These results are consistent with the notion of a ‘virtuous circle’ proposed by Sturges et al. (2002), where the adoption of career self-management behaviors by workers promotes organizational support, which in turn intensifies workers’ involvement in career self-management behaviors, and so on. This phenomenon can be explained through Blau’s social exchange theory (1964) and Gouldner’s norm of reciprocity (1960), highlighting the positive impact of advantageous exchanges between the worker and the organization and their reciprocal nature.

The empirical evidence seems to corroborate Wilhelm and Hirschi’s (2019) prediction that the relationship between organizational support and career self-management translates into increased organizational outcomes, as well as individual outcomes. Therefore, the results provide support for the reciprocal relationship between the two variables, reinforcing Orpen’s (1994) understanding that responsibility for career management should be shared by the worker and the organization.

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

This study contributes to the state-of-the-art knowledge on career self-management, specifically on the existing knowledge regarding the effect of organizational support on career self-management and vice versa. Therefore, the present systematic literature review can be relevant to guide future research.

Its results can also be useful for human resources professionals, as it presents strategies to achieve the interests of both the organization and its workers. On one hand, at the organizational level, these practices appear to promote the development of more committed and motivated teams to achieve better results. On the other hand, at the individual level, they seem to stimulate the development of skills and potentials of the worker and consequently contribute to greater career satisfaction. Furthermore, career satisfaction is negatively associated with turnover intention (Chan and Mai 2015); thus, this study enables the understanding of two factors that contribute to career satisfaction (Jung and Takeuchi 2018) and, consequently, employee retention in organizations. In this context, it is essential that the organization pays attention to its workers and offers support in managing their careers to ensure their fulfillment. To maximize individuals’ career satisfaction, the organization should encourage career self-management behaviors and provide support and resources for career development, thereby aligning the interests of both parties. This can be achieved through initiatives such as career workshops, career counseling, training opportunities, and performance evaluations, among others (Taveira 2022). For example, performance evaluations should be conducted at regular intervals rather than being spaced too far apart, and they should encompass a broader range of characteristics, including individuals’ competencies in career self-management, to provide valuable feedback (Taveira 2022).

However, the responsibility for career management should not solely rest on organizations. Considering that in career self-management, workers take control of their careers (Wilhelm and Hirschi 2019), they should focus on proactivity and engagement in career self-management behaviors, such as networking (Coetzee and Schreuder 2018). This proactive approach will enhance individuals’ engagement in their careers and, consequently, result in personal benefits. Furthermore, in line with Sturges’ virtuous circle logic (Sturges et al. 2002), such a proactive attitude may encourage organizations to respond by offering resources and organizational support.

The effect of organizational support on career self-management, as well as the inverse, proves to be extremely beneficial for both parties, resulting in increased organizational outcomes as well as individual outcomes. In this sense, we emphasize the relevance of these two practices and their competitive advantage in today’s organizational world. Moreover, we emphasize the importance of investing in scientific studies on the impact of organizational support on career self-management and vice versa in order to overcome current gaps in the literature.

5.2. Limitations

The present systematic literature review presents some limitations. Firstly, what was once the motivation for conducting this review has now become its major limitation, as the reduced number of studies found may compromise the accuracy of the results. Despite the initial number of articles being 353, many articles address only one or none of the variables. This occurs because the number of articles addressing both career self-management and organizational support is limited, attributable to the incipience of the topic. Secondly, assuming the possibility of unidentified studies due to the eligibility criteria used, and especially due to the use of the Core database which, compared to the other two, appeared not to filter studies as effectively. Thirdly, the heterogeneity of the studies made comparative analysis difficult.

Nevertheless, some limitations arise from elements of the reviewed studies, such as the lack of information on issues related to the methodology stage, namely specifics of the instruments used and the participant sample.

5.3. Future Research

Future research should explore the relationship between career self-management and organizational support, and potential mediators of this relationship, in order to address gaps in the existing literature. It would be valuable for these studies to include a diverse range of sectors, utilizing robust and representative samples, in order to generate solid data on the benefits of this relationship and its practical implications for individuals and organizations. Moreover, the study of career self-management on an individual basis is essential given the incipient nature of its research and the need to understand its dynamics with other variables.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, it is evident that the constant and rapid changes in the work environment foster feelings of insecurity regarding careers. The reviewed studies reinforce an idea already supported in the literature that career self-management benefits employees and organizations in today’s work environment. Additionally, organizational support can function as a support mechanism for the career self-management process, and vice versa. This emphasizes that the responsibility for career management should be shared between workers and organizations, rather than resting solely on one party. Furthermore, some variables have been identified as central aspects of the dynamic between career self-management and organizational support, such as managers’ emotion regulation, transformational leadership, work engagement, organizational commitment, perceived employability, and career satisfaction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M., M.d.C.T. and A.D.S.; methodology, M.M., M.d.C.T. and A.D.S.; validation, M.d.C.T., A.D.S. and F.M.; formal analysis, M.M. and A.D.S.; investigation, M.M., M.d.C.T. and A.D.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M.; writing—review and editing, M.M., M.d.C.T., A.D.S. and F.M.; supervision, M.d.C.T. and A.D.S.; funding acquisition, M.d.C.T., A.D.S. and F.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was conducted at the Psychology Research Centre (PSI/01662) of University of Minho, financially supported by the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) through the Portuguese State Budget (UIDB/01662/2020), and funds by Project Place coordinated by the Portuguese Military Academy Research Center (CINAMIL).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Akkermans, Jos, Veerle Brenninkmeijer, Marthe Huibers, and Roland W. B. Blonk. 2012. Competencies for the contemporary career: Development and preliminary validation of the Career Competencies Questionnaire. Journal of Career Development 40: 245–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachrach, Daniel G., Hui Wang, Elliot Bendoly, and Shuoyang Zhang. 2007. Importance of organizational citizenship behaviour for overall performance evaluation: Comparing the role of task interdependence in China and the USA. Management and Organization Review 3: 255–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso, Paula C. F. 2016. Gestão Pessoal de Carreira: Um Estudo com Adultos Portugueses. Master’s thesis, University of Minho, Braga, Portugal. Available online: http://repositorium.uminho.pt/handle/1822/42287 (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Baruch, Yehuda. 1999. Integrated career systems for the 2000s. International Journal of Manpower 20: 432–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, Peter M. 1964. Exchange and Power in Social Life. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Steven D., and Robert W. Lent. 2021. Career Development and Counseling: Putting Theory and Research to Work. New Jersey: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Sow H. J., and Xin Mai. 2015. The relation of career adaptability to satisfaction and turnover intentions. Journal of Vocational Behavior 89: 130–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciliato, Samia C., Lucas A. dos Santos, Vânia M. F. Costa, Carlos E. L. dos Santos, and Jaqueline C. Guse. 2019. O suporte organizacional como precedente para o comprometimento dos colaboradores. Revista Eletrônica Científica do CRA-PR-RECC 5: 64–84. Available online: https://revista.crapr.org.br/index.php/recc/article/view/158 (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Coetzee, Melinde. 2018. Career development and organizational support. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Business and Management. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzee, Melinde, and Dries Schreuder. 2018. Proactive career self-management: Exploring links among psychosocial career attributes and adaptability resources. South African Journal of Psychology 48: 206–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downes, Martin J., Marnie L. Brennan, Hywel C. Williams, and Rachel S. Dean. 2016. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open 6: e011458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dursun, Egriboyun. 2015. The relation between organizational trust, organizational support and organizational commitment. African Journal of Business Management 9: 134–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, Robert, Linda Rhoades Shanock, and Xueqi Wen. 2020. Perceived organizational support: Why caring about employees counts. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 7: 101–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, Robert, Robin Huntington, Steven Hutchison, and Debora Sowa. 1986. Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology 71: 500–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, Robert, Stephen Armeli, Barbara Rexwinkel, Patrick D. Lynch, and Linda Rhoades. 2001. Reciprocation of perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology 86: 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerber, Marius, Anette Wittekind, Gudela Grote, Neil Conway, and David Guest. 2009. Generalizability of career orientations: A comparative study in Switzerland and Great Britain. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 82: 779–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouldner, Alvin W. 1960. The Norm of Reciprocity: A Preliminary Statement. American Sociological Review 25: 161–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, Jeffrey H., Gerard A. Callanan, and Veronica M. Godshalk. 2010. Career Management. New York: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhaus, Jeffrey H., Saroj Parasuraman, and Wayne M. Wormley. 1990. Effects of race on organizational experiences, job performance evaluations, and career outcomes. Academy of Management Journal 33: 64–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, Andreas, and Jessie Koen. 2021. Contemporary career orientations and career self-management: A review and integration. Journal of Vocational Behavior 126: 103505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, Maddy, Luc Sels, and Inge Van den Brande. 2003. Multiple types of psychological contracts: A six-cluster solution. Human Relations 56: 1349–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, Baek-Kyoo, and Insuk Lee. 2017. Workplace happiness: Work engagement, career satisfaction, and subjective well-being. Evidence-Based HRM 5: 206–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Yuhee, and Norihiko Takeuchi. 2018. A lifespan perspective for understanding career self-management and satisfaction: The role of developmental human resource practices and organizational support. Human Relations 71: 73–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, Ellen E., Karen Roberts, Sandra Fisher, and Beverly Demarr. 1998. Career self-management: A quasi-experimental assessment of the effects of a training intervention. Personnel Psychology 51: 935–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtessis, James N., Robert Eisenberger, Michael T. Ford, Louis C. Buffardi, Kathleen A. Stewart, and Cory S. Adis. 2017. Perceived organizational support: A meta-analytic evaluation of organizational support theory. Journal of Management 43: 1854–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuvaas, Bård. 2008. An exploration of how the employee-organization relationship affects the linkage between perception of developmental human resource practices and employee outcomes. Journal of Management Studies 45: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Chaoping, and Kan Shi. 2005. The structure and measurement of transformational leadership in China. Acta Psychologica Sinica 37: 803–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, Robert C., and George B. Graen. 1980. Generalizability of the vertical dyad linkage model of leadership. Academy of Management Journal 23: 451–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Xin, Yilan Sha, and Xuan Yu. 2022. The impact of developmental HR practices on career self-management and organizational citizenship behavior: A moderated mediation model. Psychology Research and Behavior Management 15: 1193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Yueru, and Weibo Cheng. 2010. Differences between the dimensions of career self-management structure and demographic variables. Science and Technology Management Research 30: 130–33. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Martins, Mariana. 2023. O Suporte Organizacional na Gestão Pessoal da Carreira: Uma Revisão Sistemática da Literatura. Master’s thesis, unpublished. University of Minho, Braga, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, John P., and Natalie J. Allen. 1984. Testing the “side-bet theory” of organizational commitment: Some methodological considerations. Journal of Applied Psychology 69: 372–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, John P., Natalie J. Allen, and Catherine A. Smith. 1993. Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. Journal of Applied Psychology 78: 538–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orpen, Christopher. 1994. The effects of organizational and individual career management on career success. International Journal of Manpower 15: 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, Matthew, Joanne E. McKenzie, Patrick M. Bossuyt, Isabelle Boutron, Tammy C. Hoffmann, Cynthia D. Mulrow, Larissa Shamseer, Jennifer M. Tetzlaff, Elie A. AKL, Sue E. Brennan, and et al. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International Journal of Surgery 372: 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Jingzhou, and Wenxia Zhou. 2013. Can success lead to happiness? The moderators between career success and happiness. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 51: 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradnike, Kristina, Auksé Endriulaitiene, and Rita Bandzeviciene. 2016. Career self-management resources in contemporary career frameworks: A literature review. Organizacijø Vadyba: Sisteminiai Tyrimai 76: 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pati, Debajyoti, and Lesa N. Lorusso. 2018. How to write a systematic review of the literature. HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal 11: 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlin, Leonard I., and Carmi Schooler. 1978. The structure of coping. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 19: 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polanska, Marta A. 2016. An Empirical Investigation of Carrer Self-Management Behaviours: Test of a Theoretical Model. Master’s thesis, University Institute of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal. Available online: https://repositorio.iscte-iul.pt/handle/10071/13784 (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Scandura, Terri A., and George B. Graen. 1984. Moderating effects of initial leader-member exchange status on the effects of a leadership intervention. Journal of Applied Psychology 69: 428–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selçuk, Ayse A. 2019. A guide for systematic reviews: PRISMA. Turkish Archives of Otorhinolaryngology 57: 57–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settoon, Randall P., Nathan Bennett, and Robert C. Liden. 1996. Social exchange in organizations: Perceived organizational support, leader–member exchange, and employee reciprocity. Journal of Applied Psychology 81: 219–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, Gretchen M. 1995. Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Academy of Management Journal 38: 1442–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturges, Jane, David Guest, and Kate Mackenzie Davey. 2000. Who’s in charge? Graduates’ attitudes to and experiences of career management and their relationship with organizational commitment. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 9: 351–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturges, Jane, David Guest, Neil Conway, and Kate M. Davey. 2002. A longitudinal study of the relationship between career management and organizational commitment among graduates in the first ten years at work. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior 23: 731–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturges, Jane, Neil Conway, and Andreas Liefooghe. 2010. Organizational support, individual attributes, and the practice of career self-management behavior. Group & Organization Management 35: 108–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturges, Jane, Neil Conway, David Guest, and Andreas Liefooghe. 2005. Managing the career deal: The psychological contract as a framework for understanding career management, organizational commitment and work behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior 26: 821–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, Riki, David P. Lepak, Heli Wang, and Kazuo Takeuchi. 2007. An empirical examination of the mechanisms mediating between high-performance work systems and the performance of Japanese organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology 92: 1069–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavares, Rodrigo D. D. 2021. A perceção de suporte organizacional, conciliação vida profissional-extraprofissional e satisfação laboral: Um estudo multigeracional. Master’s thesis, Portuguese Catholic University, Porto, Portugal. Available online: https://repositorio.ucp.pt/handle/10400.14/34961 (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Taveira, Maria do Céu. 2022. Seminário Desenvolvimento de Competências na Gestão de Pessoas do Exército Português, Porto Business School, Matosinhos, Portugal. Apreciação e análise de competências para o plano de desenvolvimento individual. Personal communication. [Google Scholar]

- Tharenou, Phyllis, and Deborah J. Terry. 1998. Reliability and validity of scores on scales to measure managerial aspirations. Educational and Psychological Measurement 58: 475–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivellas, Panagiotis, Nikolaos Kakkos, Nikos Blanas, and Ilias Santouridis. 2015. The impact of career satisfaction on job performance in accounting firms. The mediating effect of general competencies. Procedia Economics and Finance 33: 468–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, Andreia F. T. 2018. Perceived Human Resources Management Practices and Career Self-Management Behaviours: Test of a Theoretical Model. Master’s thesis, University Institute of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal. Available online: https://repositorio.iscte-iul.pt/handle/10071/19736 (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Wilhelm, Francisco, and Andreas Hirschi. 2019. Career self-management as a key factor for career wellbeing. In Theory, Research and Dynamics of Career Wellbeing: Becoming Fit for the Future. Edited by Ingrid L. Potgieter, Nadia Ferreira and Melinde Coetzee. Cham: Springer, pp. 117–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Chi-Sum, and Kenneth S. Law. 2002. Wong and Law Emotional Intelligence Scale. The Leadership Quarterly. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. 2020. The Future of Jobs Report 2020. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/publications/the-future-of-jobs-report-2020/ (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Yogalakshmi, J. A., and L. Suganthi. 2020. Impact of perceived organizational support and psychological empowerment on affective commitment: Mediation role of individual career self-management. Current Psychology 39: 885–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawacki-Richter, Olaf, Michael Kerres, Svenja Bedenlier, Melissa Bond, and Katja Buntins. 2020. Systematic Reviews in Educational Research: Methodology, Perspectives and Application. Wiesbaden: Springer VS. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).