1. Introduction

Social media (SM) have increasingly become a valuable platform for communication and facilitate knowledge sharing for personal and work-life (

Ahmed et al. 2019). Organizations have widely adopted it for work-related purposes (

Chu 2020). Apart from individual usage, SM has been progressively embedded in the work environment. Organizations have been implementing SM tools in new management practices, starting from creating innovative business models to facilitating knowledge sharing, communication, and collaboration (

Cao and Yu 2019). In addition, companies have been deliberately using such social media tools to support their employees in enhancing team and employee performance, as well as improving their business activities (

Song et al. 2019;

Braojos et al. 2019).

Due to the digital era, scholars have argued that face-to-face interaction in the organization was replaced by online interaction, specifically through social media, resulting in new online social capital (

Park et al. 2013). Thus, several studies have explored the consequences of SM use on social capital in employees’ social network ties (

Huang and Liu 2017;

Park et al. 2013;

Sheer and Rice 2017;

Yen et al. 2020). Hence, social capital has become a key variable in understanding the use and implication of SM, especially in an organizational setting.

Social capital has provided a foundation for SM usage and employees’ social relations in organizations by focusing on its unique benefits on job performance. This framework was extensively used and well established, and has been widely adapted in SM-related studies e.g., (

Ali-Hassan et al. 2015;

Cao et al. 2016;

Ghorbanzadeh et al. 2021;

Kwon 2014;

Tijunaitis et al. 2019). Moreover, the three dimensions of social capital by

Nahapiet and Ghoshal (

1998) align well with the complexity of SM usage in organizations due to its multi-faceted conceptualization.

Ali-Hassan et al. (

2015) mentioned that the cognitive and relational dimensions describe a person’s ability, while the structural dimension focuses on the availability of resources. In fact, these three dimensions are obtained through employees’ relational networks (

Yan and Guan 2018).

Generally, findings from the link between SM use and job performance have been somewhat inconclusive and even contradictory. For instance, some researchers found SM usage in the workplace to be significantly associated with positive outcomes in employees’ job performance (

Eid and Al-Jabri 2016;

Jafar et al. 2019;

Lee and Lee 2020;

Song et al. 2019), while other studies state that SM use has led to a deterioration in employee performance (

Brooks 2015;

Yu et al. 2018;

Zhang et al. 2015). Hence, the inconsistent and uncertain findings of the existing studies do not explain the real impact of SM use at the workplace, whether SM usage improves or harms the employees’ innovative job performance. Furthermore, the relevance of SM usage in the workplace has been hotly debated by scholars; whether the use of SM during work time, either for personal or work-related purposes, should be allowed, disallowed, or tolerated (

Chu 2020).

Central to the present study,

Yen et al. (

2020) stated that studies of the exact mechanism of social capital and job performance through SM use for interaction between workers and coworkers are still scarce. The understanding of social media as social capital is still constrained by some persisting gaps in the social media literature, especially in innovative job performance (

Chen et al. 2019;

Ali-Hassan et al. 2015). In addition, the scope of generalizing research findings based on previous research is limited due to sample bias, affordances of SM platforms (

Sheer and Rice 2017;

Yen et al. 2020), and cultural differences (

Cao et al. 2016). Due to the limitations, the present study aimed to explore the benefits of SM use at work on employees’ innovative performance by utilizing social capital theory (SCT), and the objective of the present study is suited to the purpose of SCT.

Therefore, this study extends the model of previous studies (

Ali-Hassan et al. 2015) by incorporating work engagement in order to gain a deeper understanding of how SM use at work can foster a deep connection with social capital that directly enhances work engagement and consequently, affect employees’ innovative job performance. As

Gibbs (

1990) stated, social capital theory aims to explain the influence of people’s interaction in obtaining psychological and tangible benefits. In addition, social capital is relevant to collectivistic cultures due to the emphasis on social relationships in daily interactions, including during working hours (

Sheer and Rice 2017). Furthermore, the addition in this study of a new variable, work engagement, can be a good predictor of an employee, team, and organizational outcomes (

Bakker and Albrecht 2018).

Clausen et al. (

2019) stressed that social capital is an essential element in developing employee engagement, specifically work engagement. In addition, lack of studies on SM use and its influence on employee job performance in Malaysia (

Radhakrishnan et al. 2018), social capital is one of the critical variables in understanding the impact and outcome of SM use at work (

Sheer and Rice 2017). Consequently, the integration of SCT and work engagement will contribute to the existing body of literature in the area of SM usage and job performance from the perspective of Malaysian culture, as Malaysians in general are more collectivistic in nature (

Sumaco et al. 2014;

Jayasingam et al. 2021).

5. Results

5.1. Demographic Information

Table 2 presents the demographic information of the 291 respondents. In terms of gender, 40.5 percent (118) were male and 59.5 percent (173) were female. For the level of education, most respondents (59.5 percent) were degree holders and Masters’s degrees (23.0 percent). 28.2 percent of respondents had worked for more than 11–15 years, and 20.3 percent for 6–10 years. For SM platforms, WhatsApp (87.3 percent) and Facebook (7.6 percent) were frequently used by respondents for work-related purposes.

5.2. Common Method Bias

A statistical remedy was employed in this study to manage common method bias, which is common in behavioural research (

Podsakoff et al. 2003;

Podsakoff et al. 2012). In PLS-SEM, a full collinearity test was used to assess common method bias, and a variance inflation value (VIF) below 5.0 (

Kock 2015) and below 3.3 (

Kock and Lynn 2012) indicated the dataset did not suffer common method bias. From the test, there was no significant issue in the dataset, as the VIF values of all constructs were lower than 3.30, as shown in

Table 3.

5.3. Measurement Model

The measurement model is the first stage of using PLS-SEM that specifies the relations between the latent variable (construct) and its indicator (manifest variable). The purpose of measurement model analysis is to ensure all the required relationships between the latent variables and their indicators are met by the model assessment (

Hair et al. 2017). For construct reliability and validity, the convergent validity was evaluated by assessing the factor loadings and average variance extracted (AVE), and Cronbach alpha and composite reliability for the internal consistency reliability (

Fauzi 2021;

Chin 2010).

Table 4 shows that all the factor loadings exceed the minimum of required value 0.6 for an exploratory study (

Hair et al. 2017). The Cronbach alpha and composite reliability for all constructs were higher than the required value of 0.7 (

Hair et al. 2017).

Table 4 presents the construct validity of the measurement model for the reliability and validity analysis.

Discriminant validity is essential to ensure that each variable is distinct and not supposed to be related to each other (

Chin 2010). This study applied the Heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlation, which has a better performance for measuring the discriminant validity in variance-based SEM than the cross loadings and Fornell Larcker criterion (

Henseler et al. 2015).

Franke and Sarstedt (

2019) stated that to establish the discriminant validity that reliably distinguishes between those pairs of latent variables, a cut-off value of HTMT for conceptually dissimilar constructs should be less than 0.85, while for conceptually similar constructs, it should be less than 0.9, depending on the study context.

Table 5 shows that none of the respective constructs violates the cut-off HTMT value of 0.85, suggesting that the variables of this study possess satisfactory discriminant validity.

5.4. Structural Model

Before proceeding with the structural model assessment, the normality of data was measured by implementing Mardia’s multivariate kurtosis. The online tool available at

http://webpower.psychstat.org/models/kurtosis/ (accessed on 15 September 2022) was used to calculate univariate/multivariate skewness and kurtosis, as suggested by

Cain et al. (

2017). The results indicate that data was not multivariate normal, as shown by the skewness (

β = 5.479,

p < 0.01) and kurtosis (

β = 49.476,

p < 0.01). As suggested by

Hair et al. (

2019), this calls for a nonparametric analysis tool to perform bootstrapping.

A 5000 bootstrapping re-sampling technique was performed to assess the structural model based on the path coefficient and statistical significance (

Banjanovic and Osborne 2016). The SmartPLS 3 Version 3.6.8 bootstrapping function was used to explore the path coefficient (

β–value) of exogenous to endogenous variables, t-values, squared multiple correlation (R

2) values of explained variance on the endogenous variable, and to assess the predictive relevance of the model.

Table 6 shows the results of R

2, f

2 and Q

2, and

Table 7 displays the structural analysis results and decision on hypotheses.

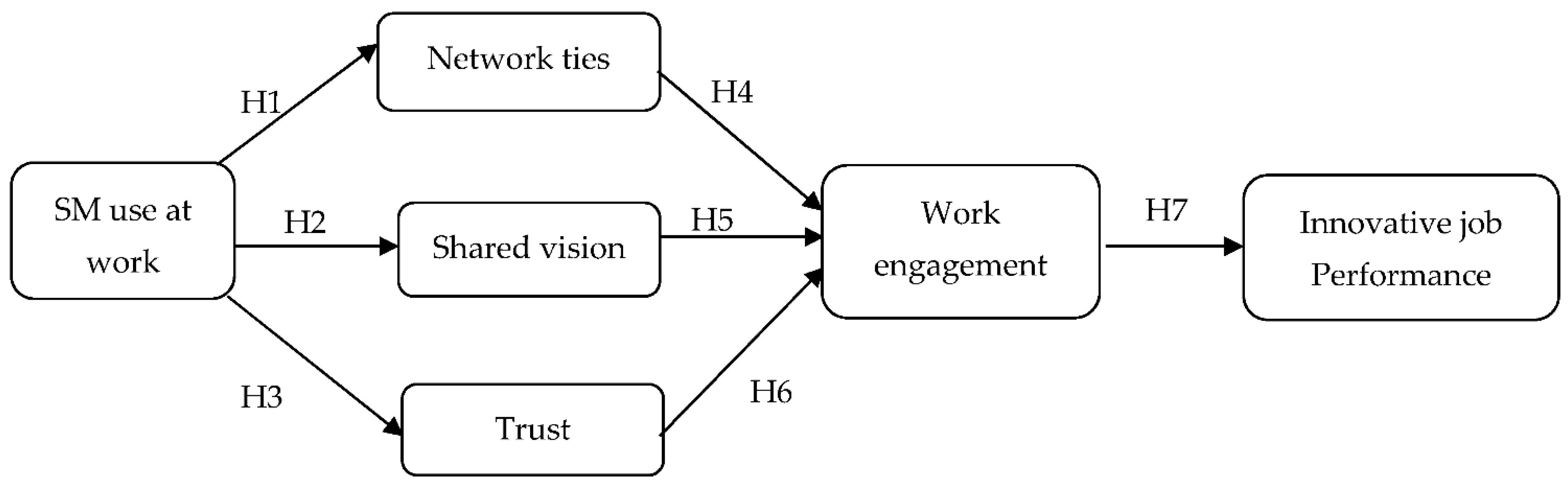

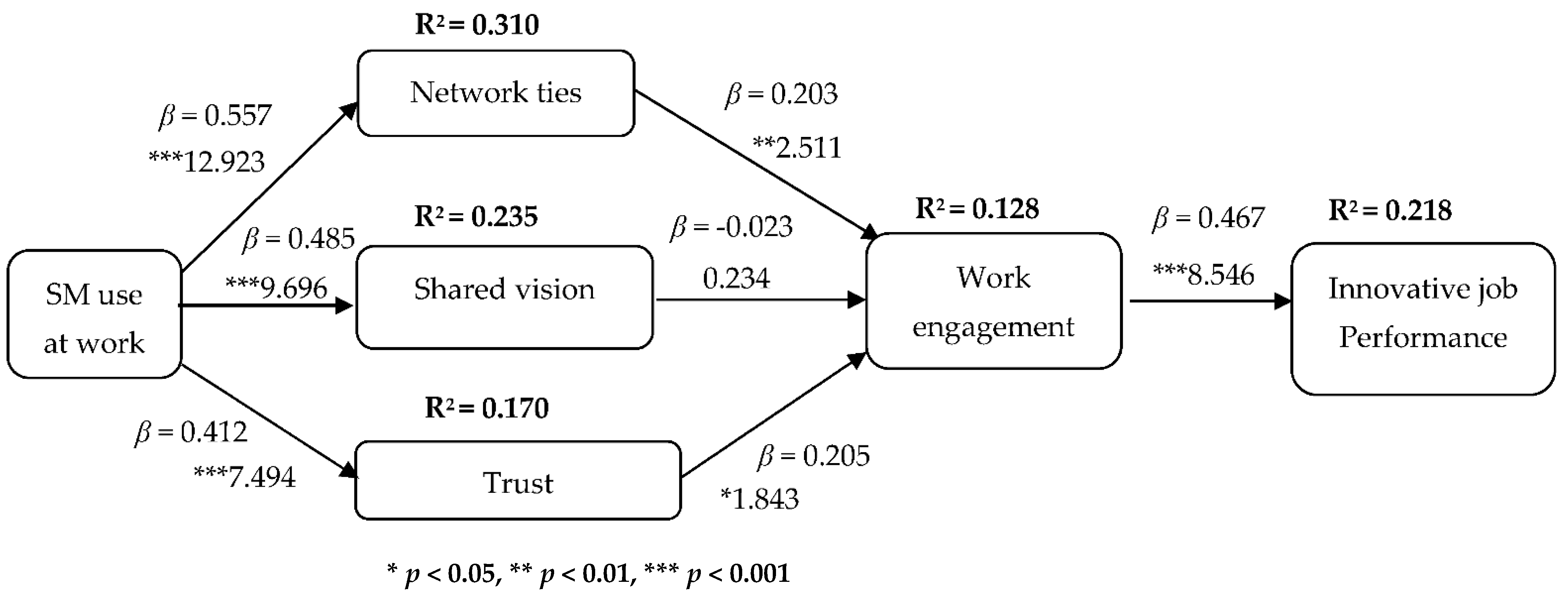

Figure 2 illustrates

β–value, t-value and R

2 of hypotheses in the structural path.

The result shows that five of the seven proposed hypotheses were supported. As hypothesized, H1, H2, and H3 were supported, as SM use at work has a positive influence on network ties (β = 0.557, t = 12.923), shared vision (β = 0.485, t = 9.696) and trust (β = 0.412, t = 7.494). The R2 of the three variables are 0.310, 0.235 and 0.170, denoting that SM use at work explained 31%, 23.5% and 17% of the variance, respectively. Next, H4 and H6 were accepted, which posited that network ties (β = 0.203, t = 2.511) and trust (β = 0.205, t = 1.843) showed a significant positive effect on employees’ work engagement, but the effect of shared vision on employees’ work engagement was not significant (β = −0.023, t = 0.234), thus rejecting H5. The R2 was 0.128, indicating that the three predictors explained 12.8% of the variance in work engagement. Lastly, H7 (β = 0.467, t = 8.546) demonstrated that work engagement was found to be significant for innovative job performance among employees, with an R2 of 0.218 indicating 21.8% of the variance in innovative job performance.

A guideline by

Cohen (

1988) has provided benchmarks in reporting effect size (f

2), which are small = 0.02, medium = 0.15 and large = 0.35.

Table 6 presents that the effect size varies from 0.000 to 0.450. This study discovered that the path of H1 has a large effect of social media use at work on network ties; meanwhile, the effect size of the path of H2, H3 and H7 are medium. However, the study discovered the insignificant path of H5, which indicated no effect of a shared vision on work engagement.

6. Discussion

The study utilized the social capital theory to explore how SM use at work predicts social capital (network ties, shared vision & trust), which affects work engagement and, subsequently, relationships on innovative job performance. Firstly, the study discovered the new outcomes of SM use and social capital in the workplace and found SM use at work predicts network ties, shared vision, and trust among Malaysian employees. Based on the findings, H1 (t = 12.923), H2 (t = 9.696), and H3 (t = 7.494) showed a t-value of more than 1.65, and these hypotheses were supported. These findings are congruent with previous studies (

Babu et al. 2020;

Huang and Liu 2017;

Cao et al. 2016;

Tijunaitis et al. 2019;

Louati and Hadoussa 2021;

Ali-Hassan et al. 2015), SM has become a platform to create network ties within an organization. The integration of SM into work-life allows employees to develop and maintain social relationships, besides becoming a supportive tool in giving support or advice to colleagues. Furthermore, the deployment of SM in the workplace helps employees exchange work-related knowledge that enhances their shared vision in executing work tasks. In addition, SM use at work can assist in spreading social information with other members of organizations, which can help develop and reinforce network ties and trust among them.

Second, the findings of this study revealed that network ties and trust promoted work engagement among Malaysian employees. The H4 (t = 2.511) and H6 (t = 1.843) were accepted as a t-value of more than 1.65, positing network ties and trust encouraged employees’ work engagement. These findings align with previous studies and emphasize that employees foster high work engagement and more satisfaction with their work when network ties and trust among colleagues are connected through SM (

Oksa et al. 2020;

Hauser et al. 2016). In structural social capital, individuals’ interactions with social networks provide them with various resources, such as advice, information, social support and other supports (

Jutengren et al. 2020). SM’s ability to provide employees with a range of benefits and resources from colleagues might enhance network ties and mutual trust with each other when they feel their relationships with colleagues are mutually supportive, resulting in high work engagement.

Meanwhile, this study found that a shared vision on employees’ work engagement was not significant as t = 0.234, t-value < 1.65, thus rejecting H5. The results indicate that a shared vision did not promote the employees’ work engagement. This finding is inconsistent with past studies (

Babu et al. 2020;

Tijunaitis et al. 2019;

Ali-Hassan et al. 2015;

Cao et al. 2016). Basically, the main components in work engagement consist of behavioral, emotional and cognitive elements, which are strongly directed toward individual work performance (

Saks 2006;

Zhang et al. 2019). Employees with high work engagement tend to immerse themselves in their work tasks cognitively, emotionally, and physically. In addition, a shared vision facilitates employees to share common collective goals and aspirations of an organization that can quickly be achieved through collaboration (

Berraies et al. 2020). In this study, employees might feel that a shared vision could not promote work engagement due to the specific job scope already assigned to them. Also, the employees understand and share a common goal and aspiration; however, they might not feel enthusiastic and inattentive with their work activities due to years of work experience. Based on the demographic information, most of the employees had long-term work experience, between 11–20 years in their field, thus influencing their motivation and level of energy to engage with their work. Furthermore, long-term work experience may lead to boredom and a repetitive routine in completing work tasks subsequently, decreasing work engagement (

van Hooff and van Hooft 2017).

Lastly, this study ascertained that work engagement was significantly associated with employees’ innovative job performance, indicating H7 (t = 8.546) t-value > 1.65. As expected, this result is in line with previous studies (

Gawke et al. 2017;

Orth and Volmer 2017). This result suggests that work engagement is a significant force that leads employees to perform with a strong focus on work. They can show their creative and critical thinking to produce, adopt, promote, and implement novel ideas. Engaged employees are associated with better task performance, high levels of creativity, client satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behavior (

Bakker et al. 2014).

7. Implication

By employing the social capital theory, this study contributes to the theoretical understanding of the role of SM use among employees in government departments. The present study provides an essential extension of current research by offering a detailed theoretical understanding of the social relationship as resources underlying employees’ work behavior, specifically in innovative job performance. In addition, this study replicates and extends SCT and research on the area of SM within the organizational context, which is essential to understand in today’s technology-driven workplaces. The outcome provides a meaningful theoretical contribution to the literature on social relations within the organization and the effects of SM use on employee outcomes at the workplace.

Employees who use SM at work may be unaware of the consequences of SM usage. They view SM as an integral part of their daily life. The importance of understanding communication needs is essential for ensuring that employees literally engage with the information. Considering the fact that SM use has become an integral part of employees’ work life, they need to have greater insight into the role of SM usage in executing the work tasks at the workplace. In addition, this study is ground-breaking in causing employees to consider SM’s usefulness as an innovative tool that can enhance their work engagement through information delivery, knowledge sharing, and facilitating relationships.

Last, the findings of this study offer management a guide to adopting an emerging and popular technology, SM, as a medium for facilitating employees’ communication, work engagement, and job performance. Such measures can effectively provide practical insights for management to create new strategies for establishing and maintaining social interaction ties that are likely to result in even more successful job performance and better decision-making. In addition, management can strengthen existing guidelines or policies regarding the terms of SM use, which may further ensure the productive and consistent use of communication channels to generate better routines and innovative performance.

8. Limitation and Future Work

Although this study offers valuable insights, certain limitations should also be acknowledged and addressed in future studies. Given the pervasiveness of SM use at work and its effects on employees’ innovative job performance, our findings imply that future research should pay closer attention to social capital, its antecedents, and its outcomes in the other type of organizational settings (i.e., private, large corporate organization) or specific industry such as manufacturing, services, and education. Different contexts would provide a detailed and diverse understanding of adapting to SM usage that may influence employees’ job performance.

Second, this study highlighted only the positive consequences of SM use in the workplace. Future studies should explore the harmful and benefits of SM use at work by integrating two theories/models (e.g., the SSO model and social capital theory). We believe that researchers in other disciplines can improve the understanding of SM use at work and employees’ outcomes from another perspective through a combination of theories.

Third, this study collected data from a single source by obtaining the responses from an internet survey only. Although the statistical result showed no issues in common method bias, respondents might be unable to inform the actual situation or condition in answering the sensitive questions related to personal relation, trust, and vision. Future scholars should consider applying a mixed-method design by adding interview sessions or observation to measure employees’ social ties and innovative job performance accurately.