Effects of ESG Activity Recognition Factors on Innovative Organization Culture, Job Crafting, and Job Performance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. ESG Management and Innovative Organization Culture

2.2. Innovative Organization Culture, Job Crafting, and Job Performance

3. Research Method

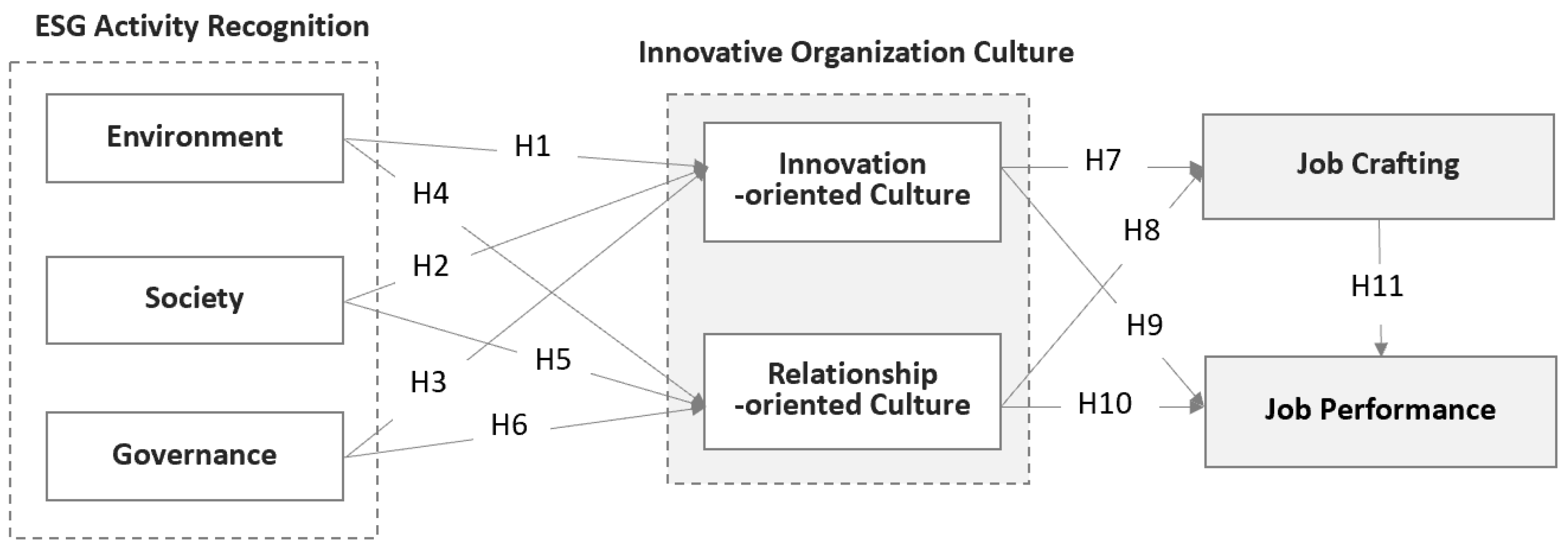

3.1. Research Model

3.2. Measurement Variables and Data Collection

3.3. Demographic Information of the Data

4. Results

4.1. Analysis Results of Reliability and Validity

4.2. Analysis Results of Structural Model and Hypothesis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Research Implications

6.2. Research Limitations and Future Plans

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Afsar, Bilal, Mariam Masood, and Waheed Ali Umrani. 2019. The role of job crafting and knowledge sharing on the effect of transformational leadership on innovative work behavior. Personnel Review 48: 1186–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsayegh, Maha Faisal, Rashidah Abdul Rahman, and Saeid Homayoun. 2020. Corporate economic, environmental, and social sustainability performance transformation through ESG disclosure. Sustainability 12: 3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aouadi, Amal, and Sylvain Marsat. 2018. Do ESG controversies matter for firm value? Evidence from international data. Journal of Business Ethics 151: 1027–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadori, Negar, Turhan Kaymak, and Mehdi Seraj. 2021. Environmental, social, and governance factors in emerging markets: The impact on firm performance. Business Strategy & Development 4: 411–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, Arnold B., Maria Tims, and Daantje Derks. 2012. Proactive personality and job performance: The role of job crafting and work engagement. Human Relations 65: 1359–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bani-Melhem, Shaker, Rachid Zeffane, and Mohamed Albaity. 2018. Determinants of employees’ innovative behavior. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 30: 1601–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, Michael L., and Robert M. Salomon. 2003. Throwing a curve at socially responsible investing research: A new pitch at an old debate. Organization & Environment 16: 381–89. [Google Scholar]

- Broadstock, David C., Roman Matousek, Martin Meyer, and Nickolaos G. Tzeremes. 2020. Does corporate social responsibility impact firms’ innovation capacity? The indirect link between environmental & social governance implementation and innovation performance. Journal of Business Research 119: 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Buccieri, Dominic, Raj G. Javalgi, and Erin Cavusgil. 2020. International new venture performance: Role of international entrepreneurial culture, ambidextrous innovation, and dynamic marketing capabilities. International Business Review 29: 101639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büschgens, Thorsten, Andreas Bausch, and David B. Balkin. 2013. Organizational culture and innovation: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Product Innovation Management 30: 763–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannas, Claudia, Maurizio Dallocchio, and Laura Pellegrini. 2022. Environmental, social, and governance issues: An empirical literature review around the world. Climate Change Adaptation, Governance and New Issues of Value 1: 107–124. [Google Scholar]

- Carmeli, Abraham, and Gretchen M. Spreitzer. 2009. Trust, connectivity, and thriving: Implications for innovative behaviors at work. The Journal of Creative Behavior 43: 169–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chams, Nour, Josep García-Blandón, and Khaled Hassan. 2021. Role reversal! Financial performance as an antecedent of ESG: The moderating effect of total quality management. Sustainability 13: 7026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, Jennifer D., and John L. Graham. 2010. Relationship-oriented cultures, corruption, and international marketing success. Journal of Business Ethics 92: 251–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chughtai, Aamir Ali, and Finian Buckley. 2011. Work engagement: Antecedents, the mediating role of learning goal orientation and job performance. Career Development International 16: 684–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornell, Bradford, and Alan C. Shapiro. 2021. Corporate stakeholders, corporate valuation and ESG. European Financial Management 27: 196–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crucke, Saskia, Tom Kluijtmans, Kenn Meyfroodt, and Sebastian Desmidt. 2022. How does organizational sustainability foster public service motivation and job satisfaction? The mediating role of organizational support and societal impact potential. Public Management Review 24: 1155–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Beer, Leon T., Maria Tims, and Arnold B. Bakker. 2016. Job crafting and its impact on work engagement and job satisfaction in mining and manufacturing. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences 19: 400–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, Manfred F. R. Kets, and Katharina Balazs. 1999. Transforming the mind-set of the organization: A clinical perspective. Administration & Society 30: 640–75. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, Edward L., and Richard M. Ryan. 2000. The” what” and” why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological inquiry 11: 227–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Yanqing, Guangming Cao, and John S. Edwards. 2020. Understanding the impact of business analytics on innovation. European Journal of Operational Research 281: 673–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernita, Firmansyah, and Tri Martial. 2020. Effect of manager entrepreneurship attitude and member motivation on organizational member participation. Management Science Letters 10: 2931–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friede, Gunnar, Timo Busch, and Alexander Bassen. 2015. ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment 5: 210–33. [Google Scholar]

- Gillan, Stuart L., Andrew Koch, and Laura T. Starks. 2021. Firms and social responsibility: A review of ESG and CSR research in corporate finance. Journal of Corporate Finance 66: 101889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillén, Arturo. 2020. Coronavirus crisis or a new stage of the global crisis of capitalism? Agrarian South: Journal of Political Economy 9: 356–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, Brage Bremset, Åshild Ønvik Pedersen, Bart Peeters, Mathilde Le Moullec, Steve D. Albon, Ivar Herfindal, Bernt-Erik Sæther, Vidar Grøtan, and Ronny Aanes. 2019. Spatial heterogeneity in climate change effects decouples the long-term dynamics of wild reindeer populations in the high Arctic. Global Change Biology 25: 3656–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, Salah, and Abeer A. Mahrous. 2019. Nation branding: The strategic imperative for sustainable market competitiveness. Journal of Humanities and Applied Social Sciences 1: 146–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, Ruth Ann, and Todd Lapidus. 2004. Collaboration, trust and innovative change. Journal of Change Management 4: 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, Suellen J., and Leonard V. Coote. 2014. Organizational culture, innovation, and performance: A test of Schein’s model. Journal of Business Research 67: 1609–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Danny Zhao-Xiang. 2021. Environmental, social and governance factors and assessing firm value: Valuation, signalling and stakeholder perspectives. Accounting & Finance 62: 1983–2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hwa Hsu, Shang, and Chun-Chia Lee. 2012. Safety management in a relationship-oriented culture. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics 18: 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jans, Nicholas A., and Anne McMahon. 1989. The comprehensiveness of the job characteristics model. Australian Journal of Psychology 41: 303–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, Frank, Alain Fayolle, and Amélie Wuilaume. 2018. Researching bricolage in social entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 30: 450–70. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Minsuck, and Boyoung Kim. 2022. The effects of ESG activity recognition of corporate employees on job performance: The case of South Korea. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 15: 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, Cheol-Keun. 2020. The Influence of innovation-oriented organizational culture on management performance-focusing on the mediating effect of proactive entrepreneurial behaviour and market orientation. Journal of Digital Convergence 18: 119–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kaštelan Mrak, Marija, and Sanda Grudić Kvasić. 2021. The mediating role of hotel employees’ job satisfaction and performance in the relationship between authentic leadership and organizational performance. Management: Journal of Contemporary Management Issues 26: 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerikmäe, Tanel, Thomas Hoffmann, and Archil Chochia. 2018. Legal technology for law firms: Determining roadmaps for innovation. Croatian International Relations Review 24: 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Moon Jun. 2020. The effect of organizational culture and job environment characteristics perceived by organization members on job satisfaction. International Journal of Internet, Broadcasting and Communication 12: 156–65. [Google Scholar]

- Kmieciak, Roman. 2020. Trust, knowledge sharing, and innovative work behavior: Empirical evidence from Poland. European Journal of Innovation Management 24: 1832–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooij, Dorien Tam, Maria Tims, and Jos Akkermans. 2017. The influence of future time perspective on work engagement and job performance: The role of job crafting. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 26: 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsantonis, Sakis, Chris Pinney, and George Serafeim. 2016. ESG integration in investment management: Myths and realities. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 28: 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Landi, Giovanni, and Mauro Sciarelli. 2018. Towards a more ethical market: The impact of ESG rating on corporate financial performance. Social Responsibility Journal 15: 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazazzara, Alessandra, Maria Tims, and Davide De Gennaro. 2020. The process of reinventing a job: A meta–synthesis of qualitative job crafting research. Journal of Vocational Behavior 116: 103267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Jae Young, and Yunsoo Lee. 2018. Job crafting and performance: Literature review and implications for human resource development. Human Resource Development Review 17: 277–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Lian, and Naoko Nemoto. 2021. Environmental, social and governance (ESG) evaluation and organizational attractiveness to prospective employees: Evidence from Japan. Journal of Accounting and Finance 21: 14–29. [Google Scholar]

- Margolis, Joshua D., and James P. Walsh. 2003. Misery loves companies: Rethinking social initiatives by business. Administrative Science Quarterly 48: 268–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Conesa, Isabel, Pedro Soto-Acosta, and Mercedes Palacios-Manzano. 2017. Corporate social responsibility and its effect on innovation and firm performance: An empirical research in SMEs. Journal of Cleaner Production 142: 2374–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKelvie, Alexander, Anna Brattström, and Karl Wennberg. 2017. How young firms achieve growth: Reconciling the roles of growth motivation and innovative activities. Small Business Economics 49: 273–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, Taryn, Sally Jeanrenaud, and John Bessant. 2020. Factors influencing the application of nature as inspiration for sustainability-oriented innovation in multinational corporations. Business Strategy and the Environment 29: 3162–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mervelskemper, Laura, and Daniel Streit. 2017. Enhancing market valuation of ESG performance: Is integrated reporting keeping its promise? Business Strategy and the Environment 26: 536–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralles-Quirós, María Mar, José Luis Miralles-Quirós, and Jesús Redondo Hernández. 2019. ESG performance and shareholder value creation in the banking industry: International differences. Sustainability 11: 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, Wan Masliza Wan, and Shaista Wasiuzzaman. 2021. Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) disclosure, competitive advantage and performance of firms in Malaysia. Cleaner Environmental Systems 2: 100015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskowitz, Howard R. 1972. Perceptual changes in taste mixtures. Perception & Psychophysics 11: 257–62. [Google Scholar]

- Nasifoglu Elidemir, Servet, Ali Ozturen, and Steven W. Bayighomog. 2020. Innovative behaviors, employee creativity, and sustainable competitive advantage: A moderated mediation. Sustainability 12: 3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortas, Eduardo, Igor Álvarez, and Ainhoa Garayar. 2015. The environmental, social, governance, and financial performance effects on companies that adopt the United Nations Global Compact. Sustainability 7: 1932–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, Carlo Bellavite, Raul Caruso, and Niketa Mehmeti. 2019. The impact of ESG scores on cost of equity and firm’s profitability. New Challenges in Corporate Govenrnace, Theory and Practice 3: 38–40. [Google Scholar]

- Piao, Xiangdan, Jun Xie, and Shunsuke Managi. 2022. Environmental, social, and corporate governance activities with employee psychological well-being improvement. BMC Public Health 22: 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachin, Nikunj, and R. Rajesh. 2022. An empirical study of supply chain sustainability with financial performances of Indian firms. Environment, Development and Sustainability 24: 6577–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassen, Remmer, Anne-Kathrin Hinze, and Inga Hardeck. 2016. Impact of ESG factors on firm risk in Europe. Journal of Business Economics 86: 867–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakil, Mohammad Hassan. 2020. Environmental, social and governance performance and stock price volatility: A moderating role of firm size. Journal of Public Affairs 22: e2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Parbudyal. 2008. Job analysis for a changing workplace. Human Resource Management Review 18: 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steen, Marie, Julian Taghawi Moussawi, and Ole Gjolberg. 2020. Is there a relationship between Morningstar’s ESG ratings and mutual fund performance? Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment 10: 349–70. [Google Scholar]

- Stock, Ruth Maria, Bjoern Six, and Nicolas A. Zacharias. 2013. Linking multiple layers of innovation-oriented corporate culture, product program innovativeness, and business performance: A contingency approach. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 41: 283–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Yafei, and Zhaohui Zhu. 2022. The effect of ESG rating events on corporate green innovation in China: The mediating role of financial constraints and managers’ environmental awareness. Technology in Society 68: 101906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, Emmarentia C., Kevin GF Thomas, and Marieta Du Plessis. 2020. An evaluation of job crafting as an intervention aimed at improving work engagement. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology 46: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Wenqing, Huatian Wang, and Sonja Rispens. 2021. How and when job crafting relates to employee creativity: The important roles of work engagement and perceived work group status diversity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, Maria, and Arnold B. Bakker. 2010. Job crafting: Towards a new model of individual job redesign. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology 36: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, Maria, Arnold B. Bakker, and Daantje Derks. 2015. Job crafting and job performance: A longitudinal study. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 24: 914–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenstra, Esmee M., and Naomi Ellemers. 2020. ESG indicators as organizational performance goals: Do rating agencies encourage a holistic approach? Sustainability 12: 10228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswesvaran, Chockalingam, and Deniz S. Ones. 2000. Perspectives on models of job performance. International Journal of Selection and Assessment 8: 216–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, Kyle, and Aaron Yoon. 2022. Do high-ability managers choose ESG projects that create shareholder value? Evidence from employee opinions. Review of Accounting Studies 27: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winklhofer, Heidi, Andrew Pressey, and Nikolaos Tzokas. 2006. A cultural perspective of relationship orientation: Using organisational culture to support a supply relationship orientation. Journal of Marketing Management 22: 169–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, Amy, and Jane E. Dutton. 2001. Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Academy of Management Review 26: 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynen, Jan, Koen Verhoest, and Bjorn Kleizen. 2017. More reforms, less innovation? The impact of structural reform histories on innovation-oriented cultures in public organizations. Public Management Review 19: 1142–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, Cengiz, Bulent Sezen, and Ozlem Ozdemir. 2005. Joint and interactive effects of trust and (inter) dependence on relational behaviors in long-term channel dyads. Industrial Marketing Management 34: 235–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Bohyun, Jeong Hwan Lee, and Ryan Byun. 2018. Does ESG performance enhance firm value? Evidence from Korea. Sustainability 10: 3635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainullin, Sergei, and Olga Zainullina. 2021. Scientific review digitalization of corporate culture as a factor influencing ESG investment in the energy sector. International Review 1: 130–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Qi, Lawrence Loh, and Weiwei Wu. 2020. How do environmental, social and governance initiatives affect innovative performance for corporate sustainability? Sustainability 12: 3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žofčinová, Vladimíra, Andrea Čajková, and Rastislav Král. 2022. Local leader and the labour law position in the context of the smart city concept through the pptics of the EU. TalTech Journal of European Studies 12: 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumente, Ilze, and Julija Bistrova. 2021. ESG importance for long-term shareholder value creation: Literature vs. practice. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 7: 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors | Survey Items | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESG Activity Recognition | Environment | (1) Our company propels carbon emissions-reducing activities and is practicing environmental management. (2) Our company supports actual investments and organizations for environmental management. (3) Our company has a performance management and evaluation system for environmental management. (4) Our company produces eco-friendly products and is offering services. | Cannas et al. (2022) Cornell and Shapiro (2021) Shakil (2020) Aouadi and Marsat (2018) |

| Society | (1) Our company is implementing a policy for its members’ employment stability. (2) Our company is evaluating by linking stakeholders’ (partner firms) environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance. (3) Our company is executing win-win partnership programs for stakeholders’ growth. (4) Our company carries out social donation and corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities for communities. | ||

| Governance | (1) Our company adopts the ethical regulations of its members. (2) Our company discloses information and issues gravely affecting organizational decision-making. (3) Our company performs continuous disclosures (publishing sustainability management reports) externally on its board of directors and information. (4) Our company holds general shareholders’ meetings and shares agenda to protect shareholders’ rights. | ||

| Innovative Organization Culture | Innovation- oriented Culture | (1) I execute and encourage innovative behaviors in various methods. (2) I highly evaluate the practical value of innovative ideas. (3) I endeavor to reflect innovative ideas at work. | Duan et al. (2020) Zhang et al. (2020) Broadstock et al. (2020) |

| Relationship- oriented Culture | (1) Our company overcomes new organizational changes well due to high consideration and reliability among members. (2) When I perform a new task, my colleagues are mutually cooperative. (3) I try to make an effort to help new and experienced employees if a change occurs within the new organization. | Hwa Hsu and Lee (2012) Steen et al. (2020) | |

| Job Crafting | (1) I always agonize about how my job is connected with organizational and company performance. (2) I think about how my job affects my life. (3) I think about how my job will contribute to our society. | Tims et al. (2015) Lee and Lee (2018) De Beer et al. (2016) | |

| Job Performance | (1) I achieve higher job performance than my colleagues. (2) I think I successfully perform work assigned to me. (3) My job performance is highly acknowledged. | Crucke et al. (2022) Kaštelan Mrak and Kvasić (2021) | |

| Classification | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 217 | 66.0 |

| Female | 112 | 34.0 | |

| Total | 329 | 100.0 | |

| Age | 25–29 | 77 | 23.4 |

| 30–39 | 153 | 46.5 | |

| 40–49 | 88 | 26.7 | |

| 50–59 | 11 | 3.3 | |

| Total | 329 | 100.0 | |

| Position | Employee (Staff) | 75 | 22.8 |

| Manager | 198 | 39.9 | |

| Division manager | 45 | 13.7 | |

| Executive | 11 | 3.3 | |

| Total | 329 | 100.0 | |

| Career | 1 year to less than 10 years | 188 | 57.2 |

| 10 years to less than 20 years | 120 | 36.5 | |

| 20 years to less than 25 years | 21 | 6.4 | |

| Total | 329 | 100.0 | |

| Job group | Production | 64 | 19.5 |

| HR/General Affairs | 54 | 16.4 | |

| R&D | 44 | 13.4 | |

| Marketing | 53 | 16.1 | |

| IT/Automation | 31 | 9.4 | |

| Finance/Accounting | 50 | 15.2 | |

| Innovation/Planning | 15 | 4.6 | |

| Others | 18 | 5.5 | |

| Total | 329 | 100.0 | |

| Variables | Question | Standard Loading Factor | SE | t-Value (p) | AVE | CR | Cronbach α | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESG Activity Recognition | Environment | 1-1 | 0.791 | - | - | 0.534 | 0.817 | 0.812 |

| 1-2 | 0.876 | 0.071 | 15.903 *** | |||||

| 1-3 | 0.616 | 0.062 | 11.090 *** | |||||

| 1-4 | 0.602 | 0.063 | 10.822 *** | |||||

| Society | 1-5 | 0.590 | - | - | 0.501 | 0.765 | 0.734 | |

| 1-6 | 0.624 | 0.145 | 8.893 *** | |||||

| 1-7 | 0.701 | 0.157 | 9.982 *** | |||||

| Governance | 1-8 | 0.547 | - | - | 0.528 | 0.767 | 0.785 | |

| 1-9 | 0.713 | 0.178 | 8.711 *** | |||||

| 1-10 | 0.749 | 0.178 | 8.846 *** | |||||

| Innovative Organization Culture | Innovation-oriented Culture | 2-1 | 0.760 | - | - | 0.613 | 0.819 | 0.843 |

| 2-2 | 0.889 | 0.087 | 15.324 *** | |||||

| Relationship-oriented Culture | 2-3 | 0.770 | - | - | 0.690 | 0.878 | 0.898 | |

| 2-4 | 0.876 | 0.111 | 15.780 *** | |||||

| Job Crafting | 3-1 | 0.883 | 0.673 | 0.860 | 0.855 | |||

| 3-2 | 0.811 | 0.053 | 18.332 *** | |||||

| 3-3 | 0.763 | 0.047 | 16.630 *** | |||||

| Job Performance | 4-1 | 0.755 | - | - | 0.710 | 0.879 | 0.876 | |

| 4-2 | 0.860 | 0.081 | 15.905 *** | |||||

| 4-3 | 0.905 | 0.081 | 16.539 *** | |||||

| Classification | E | S | G | IoC | RoC | JC | JP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environment € | 0.731 | ||||||

| Soceity (S) | 0.629 | 0.708 | |||||

| Governance (G) | 0.303 | 0.629 | 0.727 | ||||

| Innovation-oriented Culture (IoC) | 0.116 | 0.129 | 0.111 | 0.783 | |||

| Relationship-oriented Culture (RoC) | 0.296 | 0.150 | 0.175 | 0.506 | 0.831 | ||

| Job Crafting (JC) | 0.277 | 0.340 | 0.230 | 0.545 | 0.477 | 0.820 | |

| Job Performance (JP) | 0.238 | 0.185 | 0.147 | 0.257 | 0.299 | 0.560 | 0.843 |

| Hypothesis (Path) | β | B | SE | t-Value | Status of Adoption | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Environemtn -> Innovation-oriented Culture | −0.503 | −0.41 | 0.154 | −2.670 ** | Adopted |

| H2 | Soceity -> Innovation-oriented Culture | 0.822 | 1.156 | 0.454 | 2.548 * | Adopted |

| H3 | Governance -> Innovation-oriented Culture | −0.012 | −0.017 | 0.261 | −0.065 | Rejected |

| H4 | Environment -> Relationship-oriented Culture | 0.062 | 0.052 | 0.127 | 0.406 | Rejected |

| H5 | Social -> Relationship-oriented Culture | 0.098 | 0.142 | 0.368 | 0.385 | Rejected |

| H6 | Governance -> Relationship-oriented Culture | 0.326 | 0.454 | 0.231 | 1.967 * | Adopted |

| H7 | Innovation-oriented Culture -> Job Crafting | 0.515 | 0.527 | 0.084 | 6.306 *** | Adopted |

| H8 | Relationship-oriented Culture -> Job Crafting | 0.337 | 0.336 | 0.077 | 4.343 *** | Adopted |

| H9 | Innovation-oriented Culture -> Job Performance | −0.183 | −0.193 | 0.103 | −1.866 | Rejected |

| H10 | Relationship-oriented Culture -> Job Performance | 0.115 | 0.118 | 0.086 | 1.379 | Rejected |

| H11 | Job crafting -> Job Performance | 0.811 | 0.834 | 0.109 | 7.682 *** | Adopted |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jin, M.; Kim, B. Effects of ESG Activity Recognition Factors on Innovative Organization Culture, Job Crafting, and Job Performance. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12040127

Jin M, Kim B. Effects of ESG Activity Recognition Factors on Innovative Organization Culture, Job Crafting, and Job Performance. Administrative Sciences. 2022; 12(4):127. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12040127

Chicago/Turabian StyleJin, Minsuck, and Boyoung Kim. 2022. "Effects of ESG Activity Recognition Factors on Innovative Organization Culture, Job Crafting, and Job Performance" Administrative Sciences 12, no. 4: 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12040127

APA StyleJin, M., & Kim, B. (2022). Effects of ESG Activity Recognition Factors on Innovative Organization Culture, Job Crafting, and Job Performance. Administrative Sciences, 12(4), 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12040127

_김_(김).png)