Abstract

This research was designed to test and extend the model of emotional dissonance. Previous models of emotional dissonance, such as the Job Demand-Resource (JD-R) and the Stress-Strain-Outcome (SSO) models, are limited in that they do not account for the influences of work and work–family-related conflicts. The present paper focused on emotional labor carried out by married women working in call centers. We developed the model of emotional dissonance influencing intrinsic motivation and job stress, with the moderating effects of work overload and work–family conflict. The data of 468 employees analyzed using least square regression showed that that emotional dissonance is positively related to job stress, but is negatively related to intrinsic motivation. Both work overload and work–family conflict were found to be significant moderators that aggravate the positive relationships between emotional dissonance and job stress, and the negative relationships between emotional dissonance and intrinsic motivation. Theoretical and practical implications on emotional labor and emotional dissonance are discussed.

1. Introduction

The advancement of Information & Communication Technology (ICT) in the service industry allowed firms to adopt increasing use of non-face-to-face methods rather than traditional employment practices for customer service. Call centers are most commonly adopted by companies to provide customer service through ICT systems. However, call center workers frequently deal with complaints and verbal aggression from customers, experiencing greater emotional labor (Aksin et al. 2007; Rod and Ashill 2013). In such situations, workers in call centers experience inconsistent emotional harmony between the actual experiences they undergo contacting their customers and those required in accordance with the policy described in the job description of the company.

Since emotional labor can be a stressor for the workers in call centers (Pugliesi 1999) and, at the same time, customer services depend on their perceived emotions so that customers directly interact with them via telephone equipped with the ICT system, many researchers are interested in how emotional dissonance is associated with job stress and work motivation. Specifically, emotional dissonance, which is the inconsistency between the state of emotional labor processes and surfacing emotions, is likely to be linked with burnout, which lowers individual workers’ productivity and leads to psychological frustration (Bakker and Heuven 2006). Therefore, company managers recognize the emotional dissonance of workers as an important factor, especially for workers who are in direct contact with their customers through the ICT system.

However, previous studies of emotional dissonance have focused on the outcomes of emotional labor, rather than examining how emotional labor can be determined. Extant studies have sought implications for management to control the emotional dissonance of workers, rather than attempting to theorize how emotional dissonance generates the negative outcomes. Nonetheless, fruitful new attempts have focused on what causes emotional dissonance and how emotional dissonance can be aggravated under certain circumstances (Cheung and Tang 2010; Ghislieri et al. 2017; Jeon and Yoon 2017; Molino et al. 2016). Although previous studies have assumed that emotional dissonance seems more likely to appear in certain occupations, workers in the service industry that experience emotional labor are most likely to be non-regular workers and married women and, therefore, may undergo similar work experiences both in the workplace and the family (Ju et al. 2018; Reifman et al. 1991). However, few studies have focused on emotional dissonance of married and irregular women workers who are more exposed to conflicts between their workplace and family. Considering that marital adjustment of married women is a significant source of depression and stress (Hashmi et al. 2007), it is crucial to consider the psychosocial risks experienced by married women at work. In addition, since the physical and psychosocial working environment of call center employees presupposes face-to-face contact with their customers via telephone, similarly to other conventional workers in a service industry, they are more likely to be exposed to emotional labor (Norman et al. 2004). Considering the above, there is still a lack of relevant research on call center workers at present and, to the best of our knowledge, no empirical evidence focusing on the deterioration of emotional dissonance in married women working in call centers is available.

The main aims of the present study were as follows. First, we sought to examine how emotional dissonance experienced by married women working in call centers affects their job stress and intrinsic motivation. Second, we investigated the main and moderating effects of work overload and work–family conflict on the relationship between emotional dissonance and job stress, and on the relationship between emotional dissonance and intrinsic motivation. In doing so, we attempted to apply and extend previous models of emotional dissonance and seek to better describe the emotional labor of married women, especially the workers in call centers who are most likely to experience emotional dissonance, and to assess the relationship between emotional dissonance, job stress, and intrinsic motivation.

The findings of the present study provide valuable implications for researchers interested in emotional labor and emotional dissonance in call centers. Our results yield useful information for researchers and practitioners focusing on work–life balance and those having an interest in the change and development of the work environment.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Emotional Labor and Emotional Dissonance in Call Center: An Application

Unlike manual labor or cognitive labor, emotional labor has not received much scholarly attention in recent years. Nonetheless, the growth in the service industry is marked by the growing awareness of the importance of effective emotional labor management. The first researcher who used the term ‘emotional labor’ was Arlie R. Hochschild, an American sociologist. She observed the jobs of Delta flight crews and bill collectors and introduced the sociological analysis of emotional labor (Hochschild 1979). She defined emotional labor as the empowerment of a worker to control and manage his/her emotions in a way that reinforces, disguises, and hides his/her emotions so that s/he may feel. She later identified emotional regulation in the organizational rules and categorized emotional labor into surface acting and deep acting (Hochschild 1983).

Today, many companies use call centers as a marketing service channel for their customers (Jeon and Yoon 2017; Russell 2008). In a typical work environment of a call center, service agents interact with customers primarily on the phone or via other computer-aided communication channels (Van Jaarsveld and Poster 2013). Furthermore, the quality of conversations (content, style, adherence to policies) is assessed by recording and/or listening to those conversations (Aksin et al. 2007; Holman 2003; Moradi et al. 2014). For these reasons, call center work is demanding, repetitive, and often stressful, which can lead to high levels of turnover and absenteeism, in addition to the inability to meet quantitative targets (Lewig and Dollard 2003; Taylor and Bain 1999; Workman and Bommer 2004).

Previous studies identified that workers working in call centers perceive stress differently (Lewin and Sager 2007; Lin et al. 2010; Rod and Ashill 2013; Wegge et al. 2010; Zapf et al. 2003). For example, workers of call centers reported feeling stressed by consumer complaints and protests due to unreasonable demands, personality abuse, sexual harassment remarks, and a high-pressure posture, all of which can lead to psychological exhaustion or burnout caused by malicious consumers. In particular, psychosocial factors, such as poor managerial support, or limited opportunities to influence their work, influence physical and mental stress (Halford and Cohen 2003; Norman et al. 2004). At the same time, call center workers are asked to be more customer-oriented and are expected to show abilities such as remaining calm, actively listening, and being patient and empathic (Lloyd and Payne 2009).

A recent study by Biggio and Cortese (2013) emphasizes wellbeing in the workplace through the interaction between individual characteristics and organizational context. This means that job characteristics reflecting job demand and resources and, at the same time, the work and work–family-related factors, are also needed to be introduced as another stressor that influences emotional labor for call center workers. This also implies the work and work–family conflict should be considered to explain the behavior for married women working in call centers.

2.2. The Existing Models of Emotional Dissonance

The main focus of previous empirical studies can be summarized as follows. First, in earlier research on emotional dissonance, several studies investigated the relationship between emotional dissonance and emotional exhaustion, including burnout. Overall, there are two prominent models to explain the antecedents of emotional dissonance. The first model is the Job Demand-Resource (JD-R) Model. The JD-R model refers to a heuristic model that is able to specify how two different sets of working conditions may produce both health impairment and motivation (Bakker and Demerouti 2007). In this model, job demands refer to physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of a job that require sustained physical and/or psychological effort and, therefore, are associated with certain costs. Job resources represent sets of autonomy in jobs, which represents the degree of control over one’s own tasks and behavior at work (Morris and Feldman 1996). Overall, job demands themselves are not negative, but become job stressors when meeting those demands requires high effort from which the person cannot adequately recover (Meijman and Mulder 1998).

The second model is the Stress–Strain-Outcome (SSO) model devised by Koeske et al. (1993) to illustrate the stress process. Koeske et al. (1993), and later Tetrick et al. (2000), reported work stressors such as workload may influence diverse work outcomes through the mediation of emotional exhaustion. A common focus adopted in previous studies is emotional exhaustion and depletion from work overload (Koeske et al. 1993; Tetrick et al. 2000), which will eventually influence important job outcomes, such as job satisfaction.

However, although those two models of emotional dissonance would benefit from a synthesis of job characteristics with work characteristics, unfortunately, the two models used the two types of characteristics in different contexts. Since job resources are usually considered to be general resources in the JD-R model (Bakker and Demerouti 2007; Schaufeli and Taris 2014), the level of dissonance may influence job stress and work motivation in the workplace. For example, previous studies examined the mediational role of emotional dissonance in the JD-R model. Furthermore, several studies have focused on emotional dissonance as a mediator in the relationship between job characteristics and employees’ well-being (Bakker and Heuven 2006; Cheung and Tang 2007). However, few studies referred to call center work, and thus more work-related characteristics need to be explored. For example, high levels of negative emotions are associated with low levels of job stress and intrinsic motivation towards work (e.g., Jeon and Yoon 2017).

Several recent studies have applied the SSO model to the context of call center work. For example, in their study of Chinese call center and retail-shop employees, Cheung and Tang (2010) demonstrated that work characteristics, as manifested by perceived display rules, perceived performance monitoring, and perceived service culture, positively influence strain only through emotional dissonance. Furthermore, in a study of center agents, Lewis and Dollard (2003) found that emotional dissonance fully mediated the relationship between emotional demands, as expressed by the requirement to display positive emotions, and emotional exhaustion. However, work and work-related conflict can be a source of stress, and thus we need to consider those variables as stressors of emotional dissonance (e.g., Grebner et al. 2003; Karatepe 2013).

Taken together, the previous findings highlight the potential of synthesizing the two models into one framework. Accordingly, in the present study, we identify the role of job stress in reflecting the gap between job demands and resources, and examine the relationship between emotional dissonance and job stress, on the one hand, and that of emotional dissonance and intrinsic motivation, on the other hand. In this context, married female call center employees are an interesting target group to study, as the work environment involves the use of the ICT system.

2.3. The Combined Model of Emotional Dissonance: An Extension

In the present study, we apply the SSO model to examine how work stressors are associated with job stress and intrinsic motivation. In this regard, Karatepe and Aleshinloye (2009) examined the intrinsic motivation and described it as a leading factor of emotional dissonance. However, intrinsic motivation may also be the result of emotional dissonance. This implies the importance of focusing on those factors that facilitate or constrain the relationship between emotional dissonance and job stress, or the relationship between emotional dissonance and intrinsic motivation.

The present study considered the traditional categories of job demand previously identified in call center work. The first is work overload, a general demand investigated in many studies employing the JD-R model (Bakker and Demerouti 2007; Schaufeli and Taris 2014). Here, workload is referred to as the quantity of tasks and activities agents have to manage quickly, by handling calls as fast as possible (Grebner et al. 2003; Wegge et al. 2007), whereas work overload can be defined as a degree of work that was given that exceeded the worker’s ability (Ahuja et al. 2007). In addition, in the case of the proposed research model, a “Stressor–Strain–Outcome” was developed to understand the relationship between emotional dissonance and various attitudes and organizational behaviors. Therefore, we considered the work and work-related stress as moderators of emotional dissonance, and job stress and intrinsic motivation.

Although most previous literature has tended to focus on the association between emotional dissonance and display rules, we propose that emotional dissonance is positively related to work strain, which, in turn, affects job stress and intrinsic motivation. In this context, it is essential to determine the main driver of emotional dissonance of married women working in call centers. We then argue that greater attention should be paid to potential interactions between emotional dissonance and other work or work-related conflicts, and their effect on job stress and intrinsic motivation.

Call centers are a suitable venue in which to examine the SSO model, as their workers usually experience emotional dissonance and other work and work-related conflicts, which significantly influence job stress and intrinsic motivation. On careful consideration of those factors in the SSO model, a more integrated model to explain the stressor–strain relationships of emotional labor can be suggested. Although previous studies started to consider the JD-R model for job-focused emotional labor, more research is needed incorporate these into one coherent model (e.g., Cheung and Tang 2010). When applying this model to call centers, work characteristics as a stressor will lead to work strain, which will, in turn, produce negative outcomes. Based on the SSO model, potential work stressors may not exclude the issues of excessive workload and work–family conflict (Koeske et al. 1993; Tetrick et al. 2000).

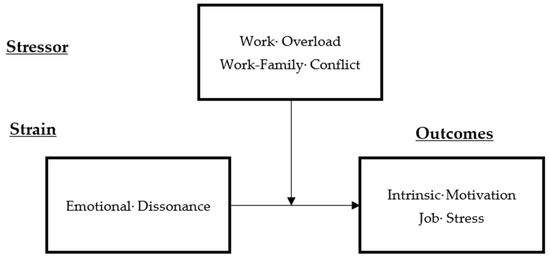

The main purpose of this study was to investigate the negative effect of emotional dissonance on the intrinsic motivation that drives the stress itself. The emotional dissonance is expected to increase the level of job stress and decrease intrinsic motivation through emotional exhaustion (Zapf et al. 1999). Those increased levels of stress and diminished intrinsic motivation can lead to negative organizational outcomes, including, among others, poor quality of service, decreased productivity, and fast employee turnover. If work–family conflicts are combined with emotional dissonance, the negative effects can be intensified to further aggravate the negative effects of emotional dissonance. Therefore, we extend the current SSO model of emotional dissonance, and then highlight the detrimental effect of work and work–family-related conflicts of the married female workers in call centers on the relationships between emotional dissonance and job stress and intrinsic motivation as an extension. Figure 1 presents the proposed model.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

3. Hypotheses Development

3.1. Emotional Dissonance and Job Stress

Job stress is defined the total amount of negative psychological responses that workers experience during job performance. In the present study, job stress is conceptualized as the negative stress that occurs in the job. Job stress, which can occur in any member of an organization, is a factor that negatively affects overall job attitudes, such as productivity, job quality, and job satisfaction.

Several recent studies have indicated that emotional dissonance can occur when members of the service-related industry become involved in emotional labor. The higher the level of emotional dissonance perceived by workers in a call center, the more likely it is that job stress will increase. The reason for this is that workers in call centers may undergo emotional pressure or confusion in identity due to the necessity to control their emotions and their attempt to show and/or feel positive emotions towards customers. For example, Rafaeli and Sutton (1989) found that workers do not feel much job stress in their emotional coordination with their actual emotional and organizational emotional norms. In the case of inconsistent emotional dissonance, job stress is significantly perceived. In addition, emotional dissonance can be a major cause of stress (Kenworthy et al. 2014), as emotional dissonance can require experiencing emotions that are different from those a person actually feels.

According to the resource conservation theory (Baumeister and Heatherton 1996), people feel stressed when facing the threat of losing their resources, when they actually lose resources, and when they do not achieve the expected results after resource investment. In addition, people tend to defend their resources, because they value their own resources rather than acquiring them, and tend to invest their own resources in both reacquisition and recovery of lost resources (Halbesleben et al. 2014). If we apply this logic to call center workers who are trained to hide their true feelings and follow the rules of emotional expression set by the organization, such as suppressing negative emotions or expressing positive emotions, we may expect them to consume more resources to hide their actual emotions. Due to the limited resources available to be used in this process, and which are available for actual job performance, one may feel a reduction in the self-control required to perform the job. This reduction in control can lead to conflicts with other employees in the job, which can lead to negative psychological consequences and job attitudes. Similarly, call center employees may use resources to perform their jobs and, as a result, become more aware of job stress (Goussinsky 2011). Thus, increased emotional dissonance would increase psychological tension by preventing the emotions from being displayed properly in an organization, which would, in turn, increase job stress (Brotheridge and Grandey 2002). Consequently, inconsistencies between the actual emotions and the emotions to be expressed appear, preventing employees from exerting emotional control. Therefore, the higher the difference between the actual emotion and the demonstrated emotion, the lower the level of emotional dissonance (as compared to the difference between the actual emotion and the demonstrated emotion). Based on this logic, the following hypothesis can be formulated:

Hypothesis 1.

There is a positive relationship between the emotional dissonance and job stress of married women working in call center.

3.2. Emotional Dissonance and Intrinsic Motivation

Although it may be reasonable to assume that the ability to affectively accomplish a given task depends on the competence and capacity of an employee, the actual performance of a job may vary depending on the desire and motivation of the employee at stake. In general, motivation can be broadly categorized into extrinsic motivation and intrinsic motivation. Whereas the former is mainly related to external material compensation, the latter has nothing to do with material compensation, but is rather associated with pleasure and satisfaction. Therefore, those employees who are satisfied and intrinsically motivated are more likely to challenge their presence and accomplish their work assignments.

However, workers in call centers are usually engaged in more than 100 phone calls per day, and are more likely to be influenced by external motivation than by internal motivation, because they do not think phone calls are a robust task or a meaningful activity. This implies that the roles and responsibilities of their jobs require intrinsic, rather than extrinsic, motivation. In this regard, a significant negative correlation between emotional dissonance and job satisfaction was previously reported (Abraham 1999; Lewig and Dollard 2003).

These intrinsic motivations of workers in call centers are expected to be low, especially when experiencing emotional dissonance. Said differently, the behavior and attitude stipulated in the manual should be performed even if a call center worker is treated unfairly in his/her interaction with a customer. In particular, even if there is emotional dissonance in a call center service, call center employees are required to control their emotions to perform the work. As a result, emotional dissonance can cause emotional exhaustion, such as exhaustion of emotional resources and energy (Bakker and Heuven 2006; Heuven and Bakker 2003; Kenworthy et al. 2014; Zapf et al. 2001). In the case of emotional exhaustion due to emotional dissonance, if the self is depleted, it will perceive an identity impairment, even for a small work assignment. It may become stressful to maintain the identity, leading to the loss of the desire to carry out the given task. Based on the above discussion, it can be inferred that the intrinsic motivation, which is the satisfaction of the task or the task itself, may be lowered or absent depending on the degree of perception of emotional dissonance. Accordingly, the following hypothesis can be formulated:

Hypothesis 2.

There is a negative relationship between emotional dissonance and intrinsic motivation of married women working in call centers.

3.3. The Moderating Effects of Work Overload

In this case, work overload can be defined as an overworked task that is difficult to effectively perform in terms of ability, time, and resources of organization members (Gilboa et al. 2008). There are consistent findings that work overload is negatively related with psychological conditions such as employees’ dissatisfaction and frustration (Spector et al. 1988). In a study by Jones et al. (2007), workers engaged in sales work and task overload were found to have a negative relationship with organizational commitment and job satisfaction. In Quick and Quick’s (1984) study, work overload was categorized into quantitative and qualitative overload; whereas the former type of overload requires excessive amounts of work to be performed within a limited period of time, the latter means exceeding the skills, abilities, competencies, and knowledge possessed by individual members.

These work overloads negatively influence workers’ personal physical fatigue, psychological anxiety, and self-esteem. If a firm requires excessive job performance from its employees, they can experience mental and physical stress, resulting in negative consequences, such as reduced commitment and increased turnover intentions (Vandenberghe et al. 2011; Wright and Cropanzano 1998). Therefore, in a work overload situation, call center workers will be able to perceive emotional dissonance, which, in turn, will increase job stress. In addition, as a result of interfering with performing core tasks, such a large amount of work is likely to prevent workers from fulfilling other tasks, which may have a detrimental effect on workers’ emotional state. As such, work overload is likely to degrade the quality of work and, under these circumstances, workers will be more disturbed by the conflict between the actual emotions and the desired emotions. This lowered self-confidence in task performance due to emotional dissonance will also eventually reduce internal motivation.

Therefore, it is likely that emotional dissonance will further strengthen the positive impact on job stress, and the negative impact on intrinsic motivation. Based on this logic and the results of previous studies, the following hypotheses can be formulated:

Hypothesis 3.

Work overload moderates the positive relationship between emotional dissonance and job stress of married women working in call centers, in such a way that work overload reinforces the positive relationship between emotional dissonance and job stress.

Hypothesis 4.

Work overload moderates the negative relationship between emotional dissonance and intrinsic motivation of married women working in call centers, in such a way that work overload reinforces the negative relationship between emotional dissonance and intrinsic motivation.

3.4. The Moderating Effects of Work–Family Conflicts

Work–family conflict can be defined as a form of role conflict that arises when the role pressures on an employee within an organization and in family life domains are incompatible (Greenhaus and Beutell 1985). This implies that various experiences of an employee in and outside of an organization s/he works in are mutually related and negatively influence each other. Therefore, conflicts between work and family can be an important source of stress in relation to emotional dissonance and, at the same time, the effects of emotional dissonance on job stress and intrinsic motivation can be further enhanced. The reason for this is that call center workers experiencing conflicts between work and family are more prone to job stress and lack of intrinsic motivation than those without conflict between work and family.

Today’s workers consider work–family balance as one of the key values; thus, work–family balance and work-related stress will play an important role when applied in the context of call center. Said differently, in the case of call center workers who perform various services at the customer contact point, negative psychological states, such as physiological tension, stress, dissatisfaction, and anxiety, can persist until after the work is completed. This means that not only business, but also management between business and home, should be prioritized.

Work–family conflicts are known to occur more often in males than in females, and more in married females than in single males. This means that dependents, including children, can be a source of disturbing stress in married people’s work life (Gutek et al. 1991; Parasuraman et al. 1996). For example, excessive commitment to work may cause conflict by hindering the role of the family and, conversely, excessive commitment to family life can amplify the conflict by interfering with the role in work. In other words, role conflicts in work and family can increase the stress associated with job performance (Kossek and Ozeki 1998), and this higher job stress can appear as a vicious cycle in which work–family conflicts can be aggravated. Although the moderating effects of work–family conflicts have not been discussed yet, we also explore the following hypotheses on the moderation effects of work–family conflicts in the relationship between emotional dissonance and job stress and intrinsic motivation.

Hypothesis 5.

Work–family conflicts moderate the positive relationship between emotional dissonance and job stress of married women working in call centers, in such a way that work–family conflicts reinforce the positive relationship between emotional dissonance and job stress.

Hypothesis 6.

Work–family conflicts moderate the negative relationship between emotional dissonance and intrinsic motivation of married women working in call centers, in such a way that work–family conflicts reinforce the negative relationship between emotional dissonance and intrinsic motivation.

4. Methods

4.1. Ethical Statement

This study involved participants through the administration of a self-report questionnaire. There were no medical treatments or other procedures that could cause psychological or social discomfort to participants, and additional ethical approval was not required.

4.2. Data Collection and Sample

The sample of this study was collected from married female workers working as counselors in 7 domestic call centers of Korean financial institutions. To obtain the data for the practical analysis, 500 questionnaires were distributed among married working women in the call centers of the Korean financial institutions for two weeks. The consent to participate in the survey was both informed and written. A total of 500 survey questionnaires were distributed, of which 494 copies were returned. Of these, 468 questionnaires were used for further analysis (valid response rate 93.6%). There was no significant difference in characteristics between the data used in the actual analysis and the data re-moved.

The demographic characteristics of the final sample are as follows; 125 (26.7%) of the participants were in their 20s, 308 (65.8%) were in their 30s, and 35 (7.5%) were in their 40s (12.2%). Furthermore, 198 (42.3%) female workers had a high school diploma, while 213 (45.5%) were college graduates. Next, over two-thirds of the participants 372 (79.5%) had children. In terms of job status, 177 (37.8%) were counselors, 255 (54.5%) were senior staff, and 36 (7.7%) were higher than the senior staff. In terms of years of service, 90 (19.2%) of the participants had work experience under 2 years, 184 (39.3%) from 2 years to 5 years, 155 (33.1%) from 5 years to 10 years, and 36 (7.7%) over 10 years. Finally, most call center workers were irregular workers (91.4%) employed through a one-year renewal contract. The number of participants who had previous turnover experience was 300 (64.1%).

4.3. Measurements

Independent Variable: Emotional dissonance was defined as “the felt conflict between the way one feels toward interaction partners and the emotion one feels compelled to display toward those individuals” (Rutner et al. 2008, p. 636). The conceptual definition of emotional dissonance can be explained in a different way. For example, Morris and Feldman (1996) capture emotional dissonance with three items (e.g., “Most of the time, the way I act and speak with patients matches how I feel anyway”). We measured the emotional dissonance variable using four items proposed by Cheung and Cheung (2013), and Rutner and his colleagues (2008). Five-point Likert-type scales ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) were used for all measures.

Dependent Variables: We examined the influences of emotional dissonance on job stress and intrinsic motivation. First of all, job stress was defined as “physical and psychological anxiety emanating from interaction between person and job” (Beehr 1985). As argued by Newman and Beehr (1979), psychological imbalance reflects the psychological responses of the individual to their job that may occur when the job demands exceed the expectations of the individual. We measured the job stress variable using ten items proposed by Parker and DeCotiis (1983).

Next, intrinsic motivation was defined as “satisfaction with self-actualization and own work”. In this regard, Deci and Ryan (1985) described intrinsic motivation as a state of commitment through the sense of accomplishment or challenge that an employee achieves by performing a task. We measured intrinsic motivation variable using five items of the questionnaire proposed by Tierney et al. (1999).

Moderators: We examined the moderating effects of work overload and work–family conflict on the effects of emotional dissonance on job stress and intrinsic motivation. First, work overload can be defined as “the degree of work that was given too much in terms of the ability and time of the individual” (Ahuja et al. 2007), and was measured with four items used by Ahuja and his colleagues (2007). Next, the work–family conflict is defined as “a form of role conflict that arises when it is difficult to reconcile role expectations arising from work and family” (Adams et al. 1996). We measured work–family conflict with five items developed by Adams and his colleagues (1996).

Controls: Multiple regression analysis and hierarchical regression analysis were conducted to test the hypotheses. First, to control for the effect of demographic variables, gender, age, education level, grade, and years of service were used as control variables. Following previous research (e.g., Deery et al. 2002), the number of turnovers was also controlled for.

4.4. Analyses

The reliability and validity of the measurement tools were verified based on the measure validation proposed by Nunnally and Bernstein (1994). The first item of the questionnaire was assessed according to the method proposed by Churchill (1979). The questionnaire items with a corrected item-to-total correlation of less than 0.40 were removed. As a result, reliability using Cronbach’s alpha was found to be 0.838; intrinsic motivation, 0.944; job stress, 0.963; work overload, 0.864; and work–family conflict, 0.965. Therefore, the reliability of the measurement tools used in this study was relatively satisfactory; Nunnally and Bernstein (1994) applied the criteria of 0.60 or higher. Factor analysis was conducted to verify the validity of the measurement tools.

As a result of the analysis presented in Table 1, all items satisfied the load of ± 0.50 or more.

Table 1.

Results of the principal component analysis with oblique rotation.

Principal component analysis was adopted as a factor analysis method and a right-angle rotation method was selected. As a result of the analysis, all items satisfied the load of ± 0.50 or more. Therefore, it was concluded that the measurement items that had undergone the purification procedure and the single dimensional verification procedure had a high level of validity. SPSS 24.0 was used to perform hierarchical regression analyses to examine the hypothesized model.

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

As shown in Table 2, highly significant associations among the variables of interest were observed. First, emotional dissonance had a positive relationship with job stress (r = 0.334) and negative association with intrinsic motivation (r = −0.156). Next, job stress and intrinsic motivation were negatively correlated (r = −0.174). In the case of high work overload, intrinsic motivation was low (r = −0.301) and there were negative and significant correlations between work–family conflict and intrinsic motivation (r = −0.297). Finally, although work overloading was more highly correlated with emotional dissonance (r = 0.109), the correlation between emotional dissonance and work–family conflict was not significant.

Table 2.

Mean, standard deviation, and Pearson correlations.

5.2. Regression Results

We performed multiple and hierarchical regression analyses to test the hypotheses (see Table 3 and Table 4 for a summary of the results). Gender, age, educational background, job title, tenure, and number of turnovers were used as control variables.

Table 3.

The regression results of emotional dissonance on job stress.

Table 4.

The regression results of emotional dissonance on intrinsic motivation.

The results of multiple regression analyses to verify the relationships between emotional dissonance and job stress are shown in Table 3; the results regarding intrinsic motivation are presented in Table 4. The hierarchical regression analyses to verify the moderating effects of work overload and work–family conflict are also presented in Table 3 and Table 4. The variance inflation factor (VIF) was less than 10 in the regression equation, and thus the problem of multicollinearity did not appear.

As shown in Table 3, the results of regression Model2 showed that the regression equation with emotion dissonance as an independent variable had the explanatory power of 32.2% (R2 = 0.322). Regarding the significance of the variables, emotional dissonance had statistically significant and positive influences on job stress (p < 0.001). Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was supported. In addition, as shown in Table 4, the results of regression Model 2 show that 18.8% (R2 = 0.188) of the regression equation with emotional incongruence as an independent variable had explanatory power. Regarding the significance of the variables, emotional dissonance affected the intrinsic motivation in the negative direction and was statistically significant (p < 0.01). Therefore, Hypothesis 1 was also supported by the results of our analyses.

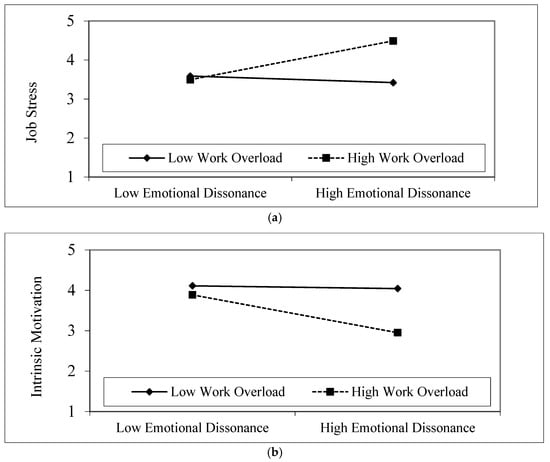

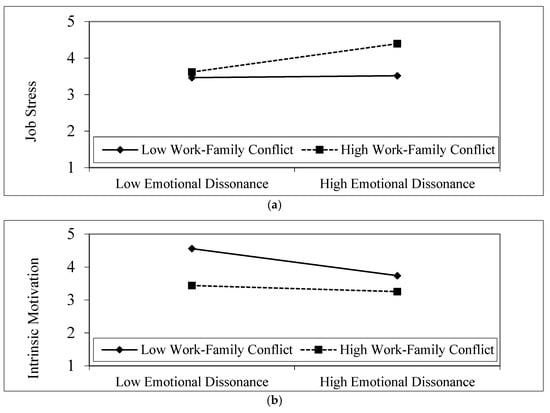

In hypothesis 3 and 5, we proposed that work overload and work-family conflict will strengthen the positive relationship between emotional dissonance and job stress. We found that work overload and work–family conflict strengthened the relationship between emotional dissonance and job stress. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 (b = 0.290, p < 0.01) and Hypothesis 5 (b = 0.181, p < 0.01) were supported by our results. These effects are shown in Figure 2a and Figure 3a. Furthermore, in Hypotheses 4 and 6, we suggested that work overload and work-family conflict will reinforce the negative relationship between emotional dissonance and intrinsic motivation. Although Hypothesis 4 was supported (b = −0.217, p < 0.001), Hypothesis 6 was not (b = 0.159, p < 0.01). The nature of these effects is shown in Figure 2b and Figure 3b.

Figure 2.

(a) The moderating effects of work overload on intrinsic motivation. (b) The moderating effects of work overload on intrinsic motivation.

Figure 3.

(a) The moderating effects of work–family conflict on job stress. (b) The moderating effects of work–family conflict on intrinsic motivation.

6. Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate the moderating effects of work overload and work–family conflict in order to examine the relationships between emotional dissonance and job stress, and between emotional dissonance and intrinsic motivation in call centers of Korean financial institutions. Specifically, we sought to find out if there was a positive relationship between emotional dissonance and job stress, and to examine the negative relationship between emotional dissonance and intrinsic motivation, and to explore the moderating effects of work overload and work–family conflict. To obtain data for the practical analysis, 500 questionnaires were distributed among married working women in seven call centers of Korean financial institutions. A total of valid 468 questionnaires were gathered and used for further analysis (valid response rate 93.6%).

Our findings regarding the hypotheses testing can be summarized as follows. First, our results consistently show that emotional dissonance has a positive effect on job stress and a negative effect on intrinsic motivation. Second, we found that work overload is a moderator between emotional dissonance and intrinsic motivation and, at the same time, work–family conflicts were shown to have moderating effects on the relationship between emotional dissonance and job stress, and emotional dissonance and intrinsic motivation.

These findings provide the following implications. First, emotional dissonance plays an important role for increasing job stress, while emotional dissonance has negative effects on intrinsic motivation. In this study, we confirmed that, due to emotional dissonance, employees in call centers have experienced negative psychological, emotional, and physical reactions. Usually, call center workers are expected to achieve customers’ satisfaction via telephone contact with their customers, which means their emotions should be evident, as described in the employee manual, but their emotional expressions must be carefully controlled. Without changing the manner of interacting with customers, increased job stress may cause unintended dissatisfaction with their jobs, because customers’ satisfaction in their contact with employees in call centers is hard to attain due to the current employment and program for emotional labor. Thus, we can conclude that the higher the strength of emotional labor, the higher the dissatisfaction with the job and the depletion of mental resources (e.g., Abraham 1999).

Second, our results show that work overload has moderating effects on the relationship between emotional dissonance and intrinsic motivation. The conventional models of emotional dissonance have suggested that job stress may drive employee’s exhaustion, but did not carefully consider job stress as an outcome of emotional dissonance. Moreover, Abraham (1998) argued that there was a need to identify contingencies that may mitigate or strengthen the negative effects of emotional dissonance. Considering that emotional dissonance entails a discrepancy between socially prescribed and true emotions, it is important to understand the role of work context. However, recent studies investigating the effect of emotional dissonance in organizations failed to consider contextual effects, but focused on individual factors such as age or self-efficacy (e.g., Indregard et al. 2018). Therefore, our results suggest that work overload can be a source of emotional dissonance and, at the same time, moderate the relationship between emotional dissonance and job stress, in addition to that between emotional dissonance and intrinsic motivation.

Finally, the results of the present study show that work–family conflict has moderating effects on the relations between emotional dissonance and job stress. This study focused on married women working in call centers in South Korea. It is also true that married women have a relatively more important role in family life than married men (although there have been some changes to the distribution of gender roles in the modern society). In addition, psychological disparities in the call center workplace are likely to cause various conflict at home. The results of the empirical analysis directly confirm that the work–family conflict is part of a vicious cycle of increasing job stress in the workplace.

6.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

This study provides the following theoretical and practical implications. First, as predicted, call center workers are exposed to emotional dissonance by encountering various customers and, in situations when emotional dissonance of call center workers is high, job stress is also high and internal motivation is low. Based on these results, we suggest that officers of call centers need to manage the emotional dissonance of employees in call centers where job stress is usually high and intrinsic motivation is low. Reducing the emotional dissonance is more likely to reduce the level of job stress, and restore the intrinsic motivation; therefore, this means of decreasing the emotional labor of employees can increase the productivity of call centers. The introduction of various psychological programs that address the emotional dissonance of employees working in call centers will minimize the side effects that may arise from emotional dissonance.

Second, the results of this study suggest that emotional dissonance of female workers working in call centers results in a higher job stress and a lower intrinsic motivation compared to a large job overload. This means that work overload can be a major stressor because it may deplete individuals’ limited resources to complete their jobs. In contrast to previous studies that noted the limited role of work overload (e.g., Rutner et al. 2008), the present study revealed the importance of work overload on the effect of emotional dissonance and outcomes. The current study successfully indicated that work overload is associated with individual emotional dissonance, which leads to more job stress and lower intrinsic motivation. Our results clearly suggest that excessive work overloads of female workers working in call centers act as another stressor to increase job stress, and decrease intrinsic motivation. However, at the same time, these factors moderate the relationship between emotional dissonance and work attitude, such as job stress and intrinsic motivation. Various job-related anxiety factors can be eliminated to create realistic means to reduce work overload, but it is still necessary to carefully consider how to convert regular workers to non-regular workers who work in call centers.

Third, we found that work–family conflicts have a significant effect on the job stress of female workers in call centers and on the reduction in internal motivation. Previous studies investigated the possible effect that stress has on work–family conflict (Rabenu et al. 2017) or that work–family conflict has on stress (Judge and Colquitt 2004). However, married women working in call centers are exposed to an excessive work environment and work-related conflicts. Our results suggest that women who work in call centers are more likely to experience various work–family conflicts and, accordingly, the higher level of work–family conflicts among married female workers increases job stress. In this way, various schemes may be required to prevent work–family conflict from becoming a source of job stress, because emotional dissonance increases the effect of job stress and lowers intrinsic motivation. In this case, the adoption of family-friendly systems for married women will help solve various problems faced by female workers of call centers. This means that control should not only focus on work-related conflict, but should also consider work–family conflict, to enhance job performance and change attitudes toward jobs for married woman working in call centers.

6.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

The limitations of this study and future research directions are as follows. First, this study was based on the data from a single survey method and workers in call centers self-reported their opinions, which may have resulted in errors and bias. In order to address this limitation, it is necessary to collect data from different sources. In addition, although all the hypotheses tested in the present study were supported by the data analysis, causality was not confirmed. This may be because we used cross-sectional data at a certain point in time, and errors may exist in the causal relationship among the variables of concern. Therefore, it would be better to collect data at different points in time and check for possible endogenous problems to identify true causality, so that the model of emotional dissonance can confirm a more accurate causal relationship for job stress or intrinsic motivation.

Second, this study focused on the empirical data obtained from married women working in call centers; therefore, the target population can impose limitations on the generalizability of our results. Of course, as predicted, the results of the present analysis show that women working in call centers who felt emotional dissonance have experienced higher job stress and lower intrinsic motivation. This means that, without addressing their emotional dissonance, women working in call centers are unable to perform their jobs properly. Although these findings cannot be generalized to organizations other than call centers, it is important to analyze and compare the differences among people of different occupations (e.g., Jeon and Yoon 2017; Martins et al. 2002). In future research, more studies are needed to compare married and unmarried women working in call centers. It is also necessary to collect data that can compare the characteristics of various occupations or organizations to determine the true relationship between emotional dissonance and job stress or intrinsic motivation (e.g., Bakker and Heuven 2006; Lewig and Dollard 2003). By doing so, a more comprehensive understanding of the application of the emotional dissonance model can be achieved.

In this study, we tested and applied the emotional dissonance model, i.e., the SSO model of Koeske et al. (1993), and extended it with the JD-R model to explain the phenomenon of emotional dissonance in call centers and to examine emotional dissonance in more detail (e.g., Molino et al. 2016). Although our results contributed to both of these previous studies, the relationships between emotional dissonance and job stress or intrinsic motivation can be further elaborated by exploration of other predictors. This means that future researchers may also benefit from analyzing different outcomes of the SSO model, such as connecting the model to significant organizational behaviors beyond job stress and intrinsic motivation (e.g., Cheung and Cheung 2013; Cheung and Tang 2010). Moreover, in order to propose a more comprehensive model among the variables of interest, or to consider different moderating variables to compare individual differences, it is also necessary to examine the mediating effect of emotional dissonance (e.g., Cheung and Tang 2010; Van Dijk and Brown 2006). In this context, we suggest that self-control or self-monitoring would be appropriate variables to provide a legitimate explanation for comparing the results (e.g., Abraham 1999; Diestel and Schmidt 2010).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Y. and M.-K.J.; methodology, M.-K.J.; software, M.-K.J.; validation, H.Y. and M.-K.J.; formal analysis, M.-K.J.; investigation, M.-K.J.; resources, H.Y.; data curation, M.-K.J.; writing—original draft preparation, M.-K.J.; writing—review and editing, H.Y. and Y.Y.; visual-ization, Y.Y.; supervision, Y.Y.; project administration, H.Y.; funding acquisition, H.Y. and Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abraham, Rebecca. 1998. Emotional dissonance in organizations: Antecedents, consequences, and moderators. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs 124: 229. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abraham, Rebecca. 1999. Negative affectivity: Moderator confound in emotional dissonance-outcome relationships? The Journal of Psychology 133: 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, Gary, Lynda A. King, and Daniel W. King. 1996. Relationships of job and family involvement, family social support, and work–family conflict with job and life satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology 81: 411–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, Manju. K., Katherine M. Chudoba, Charles J. Kacmar, D. Harrison McKnight, and Joey F. George. 2007. IT road warriors: Balancing work-family conflict, job autonomy, and work overload to mitigate turnover intentions. MIS Quarterly 31: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksin, Zeynep, Mor Armony, and Vijay Mehrotra. 2007. The modern call-center: A multi-disciplinary perspective on operations management research. Production and Operations Management 16: 665–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Arnold B., and Evangelia Demerouti. 2007. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Management Psychology 22: 309–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Arnold B., and Ellen Heuven. 2006. Emotional dissonance, burnout, and in-role performance among nurses and police officers. International Journal of Stress Management 13: 423–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, Roy F., and Todd F. Heatherton. 1996. Self-regulation failure: An overview. Psychology Inquiry 7: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beehr, Terry A. 1985. The role of social support in coping with organizational stress. In Human Stress and Cognition in Organizations: An Integrated Perspective. Edited by Terry A. Beehr and Rabi S. Bhagat. New York: John Wiley and Sons, pp. 375–98. [Google Scholar]

- Biggio, Gianluca, and Claudio G. Cortese. 2013. Well-being in the workplace through interaction between individual characteristics and organizational context. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health Well-Being 8: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotheridge, Céleste M., and Alicia A. Grandey. 2002. Emotional labor and burnout: Comparing two perspectives of “people work”. Journal of Vocational Behavior 60: 17–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, Francis, and Ray Yu-Hin Cheung. 2013. The effect of emotional dissonance on organizational citizenship behavior: Testing the stressor-strain-outcome model. Journal of Psychology 147: 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, Francis, and Catherine Tang. 2007. The influence of emotional dissonance and resources at work on job burnout among Chinese human service employees. International Journal of Stress Management 14: 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, Francis, and Catherine Tang. 2010. The influence of emotional dissonance on subjective health and job satisfaction: Testing the stress-strain-outcome model. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 40: 3192–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, Gilbert A. Jr. 1979. A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. Journal of Marketing Research 16: 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, Edward L., and Richard M Ryan. 1985. The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. Journal of Research in Personality 19: 109–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deery, Stephen, Roderick Iverson, and Janet Walsh. 2002. Work relationships in telephone call centers: Understanding emotional exhaustion and employee withdrawal. Jornal of Management Studies 39: 471–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diestel, Stephen, and Klaus-Helmut Schmidt. 2010. Interactive effects of emotional dissonance and self-control demands on burnout, anxiety, and absenteeism. Journal of Vocational Behavior 77: 412–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghislieri, Chiara, Federica Emanuel, Monica Molino, Claudio G. Cortese, and Lara Colombo. 2017. New technologies smart, or harm work-family boundaries management? gender differences in conflict and enrichment using the JD-R theory. Frontiers in Psychology 8: 1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilboa, Simona, Arie Shirom, Yitzhak Fried, and Cary Cooper. 2008. A meta-analysis of work demand stressors and job performance: Examining main and moderating effects. Personnel Psychology 61: 227–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goussinsky, Ruhama. 2011. Customer aggression, emotional dissonance and employees’ well-being. International Journal of Quality and Service Science 3: 248–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grebner, Simone, Norbert Semmer, Luca Lo Faso, Stephen Gut, Wolfgang Kalin, and Achim Elfering. 2003. Working conditions, well-being and job related attitudes among call centre agents. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 12: 341–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, Jeffrey H., and Nicholas J. Beutell. 1985. Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review 10: 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutek, Barbara A., Sabrina Searle, and Lilian Klepa. 1991. Rational versus gender role explanations for work-family conflict. Journal of Applied Psychology 76: 560–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, Jonathon R. B., Jean-Pierre Neveu, Samantha C. Paustian-Underdahl, and Mina Westman. 2014. Getting to the “COR”: Understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. Journal of Management 40: 1334–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halford, Victoria, and H. Harvey Cohen. 2003. Technology use and psychosocial factors in the self-reporting of musculoskeletal disorder symptoms in call center workers. Journal of Safety Research 34: 167–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, Hina Ahmed, Maryam Khurshid, and Ishtiaq Hassan. 2007. Marital adjustment, stress and depression among working and non-working married women. Internet Journal of Medical Update 2: 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuven, Ellen M., and Arnold Bakker. 2003. Emotional dissonance and burnout among cabin attendants. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 12: 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochschild, Arlie Russell. 1983. The Managed Heart. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild, Arlie Russell. 1979. Emotion work, feeling rules, and social structure. American Journal of Sociology 85: 551–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, David. 2003. Call centres. In The New Workplace: A Guide to the Human Impact of Modern Working Practices. Edited by David Holman, Toby D. Wall, Chris W. Clegg, Paul Sparrow and Ann Howard. Chichester: Wiley, pp. 115–34. [Google Scholar]

- Indregard, Anne-Marthe R., Stein Knardahl, and Morten B. Nielsen. 2018. Emotional dissonance, mental health complaints, and sickness absence among health-and social workers. The moderating role of self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology 9: 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Moo-Kyeong, and Hyunjoong Yoon. 2017. The relationship between emotional dissonance and intrinsic motivation: Focusing on work-family conflict. Journal of Distribution Science 15: 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Eli, Lawrence Chonko, Deva Rangarajan, and James Roberts. 2007. The role of overload on job attitudes, turnover intentions, and salesperson performance. Journal of Business Research 60: 663–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Yeong Jun, Eun-Cheol Park, Hyun-Jun Ju, Sang Ah Lee, Joo Eun Lee, Woorim Kim, and Sung-Youn Chun & Tae Hyun Kim. 2018. The influence of family stress and conflict on depressive symptoms among working married women: A longitudinal study. Health Care for Women International 39: 275–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Judge, Timothy A., and Jason A. Colquitt. 2004. Organizational justice and stress: The mediating role of work-family conflict. Journal of Applied Psychology 89: 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karatepe, Osman M. 2013. The effects of work overload and work-family conflict on job embeddedness and job performance: The mediation of emotional exhaustion. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 25: 614–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, Osman M., and Kayode Dare Aleshinloye. 2009. Emotional dissonance and emotional exhaustion among hotel employees in Nigeria. International Journal of Hospitality Management 28: 349–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenworthy, Jared, Cara Fay, Mark Frame, and Robyn Petree. 2014. A meta-analytic review of the relationship between emotional dissonance and emotional exhaustion. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 44: 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeske, Gary. F., Stuart A. Kirk, and Randi D. Koeske. 1993. Coping with job stress: Which strategies work best? Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 66: 319–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, Ernst Ellen, and Cynthia Ozeki. 1998. Work–family conflict, policies, and the job–life satisfaction relationship: A review and directions for organizational behavior–human resources research. Journal of Applied Psychology 83: 139–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewig, Karey A., and Maureen F. Dollard. 2003. Emotional dissonance, emotional exhaustion, and job satisfaction in call centre workers. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 12: 366–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, Jeffrey. E., and Jeffrey K. Sager. 2007. A process model of burnout among salespeople: Some new thoughts. Journal of Business Research 60: 1216–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Yen-Hui, Chih-Yong Chen, Wei-Hsien Hong, and Yu-Chao Lin. 2010. Perceived job stress and health complaints at a bank call center: Comparison between inbound and outbound services. Industrial Health 48: 349–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lloyd, Caroline, and Jonathan Payne. 2009. Full of sound and fury, signifying nothing’ interrogating new skill concepts in service work-the view from two UK call centres. Work, Employment and Society 23: 617–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, Luis L., Kimberly A. Eddleston, and John F. Veiga. 2002. Moderators of the relationship between work-family conflict and career satisfaction. Academy of Management Journal 45: 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijman, Theo F., and Gijsbertus Mulder. 1998. Psychological aspects of workload. In Handbook of Work and Organizational Psychology. Edited by Pieter J. D. Drenth, Henk Thierry and Charles J. de Wolff. Hove: Psychology Press, Volume 2, pp. 5–33. [Google Scholar]

- Molino, Monica, Federica Emanuel, Margherita Zito, Chiara Ghislieri, Lara Colombo, and Claudio G. Cortese. 2016. Inbound call centers and emotional dissonance in the job demands-resources model. Frontiers in Psychology 7: 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moradi, Saleh, Ali A. Nima, Max Rapp Ricciardi, Trevor Archer, and Danilo Garcia. 2014. Exercise, character strengths, well-being, and learning climate in the prediction of performance over a 6-month period at a call center. Frontiers in Psychology 5: 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J. Andrew, and Daniel C. Feldman. 1996. The dimensions, antecedents, and consequences of emotional labor. Academic. Management Review 21: 986–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, John E., and Terry A. Beehr. 1979. Personal and organizational strategies for handling job stress: A review of research and opinion. Personnel Psychology 32: 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, Kerstin, Tohr Nilsson, Mats Hagberg, Ewa Wigaeus Tornqvist, and Allan Toomingas. 2004. Working conditions and health among female and male employees at a call center in Sweden. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 46: 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, Jum C., and Ira H. Bernstein. 1994. Psychometric Theory. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Parasuraman, Saroj, Yasmin S. Purohit, Veronica M. Godshalk, and Nicholas J. Beutell. 1996. Work and family variables, entrepreneurial career success, and psychological well-being. Journal of Vocational Behavior 48: 275–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, Donald F., and Thomas A. DeCotiis. 1983. Organizational determinants of job stress. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 32: 160–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugliesi, Karen. 1999. The consequences of emotional labor: Effects on work stress, job satisfaction, and well-being. Motivation and Emotion 23: 125–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quick, James C., and Jonathan D. Quick. 1984. Organizational Stress and Preventive Management. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Rabenu, Edna, Aharon Tziner, and Gil Sharoni. 2017. The relationship between work-family conflict, stress, and work attitudes. International Journal of Manpower 38: 1143–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafaeli, Anat and Robert I. Sutton. 1989. The expression of emotion in organizational life. Research of Organizational Behavior 11: 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Reifman, Alan, Monica Biernat, and Eric L. Lang. 1991. Stress, social support, and health in married professional women with small children. Psychology of Women Quarterly 15: 431–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rod, Michel, and Nicholas J. Ashill. 2013. The impact of call centre stressors on inbound and outbound call-centre agent burnout. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal 23: 245–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, Bob. 2008. Call centres: A decade of research. International Journal of Management Reviews 10: 195–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutner, Paige S., Bill C. Hardgrave, and D. Harrison McKnight. 2008. Emotional dissonance and the information technology professional. MIS Quarterly 32: 635–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, Wilmar B., and Toon W. Taris. 2014. A critical review of the job demands-resources model: Implications for improving work and health. In Bridging Occupational, Organizational and Public Health: A Transdisciplinary Approach. Edited by Georg Bauer and Oliver Hämming. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 43–68. [Google Scholar]

- Spector, Paul E., Daniel J. Dwyer, and Steve M. Jex. 1988. Relation of job stressors to affective, health, and performance outcomes: A comparison of multiple data sources. Journal of Applied Psychology 73: 11–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Phil, and Peter Bain. 1999. An assembly line in the head: The call centre labour process. Industrial Relations Journal 30: 101–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetrick, Lois E., Kelley J. Slack, Nancy Da Silva, and Robert R. Sinclair. 2000. A comparison of the stress–strain process for business owners and nonowners: Differences in job demands, emotional exhaustion, satisfaction, and social support. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 5: 464–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, Pamela, Steven M. Farmer, and George B. Graen. 1999. An examination of leadership and employee creativity: The relevance of traits and relationships. Personnel Psychology 52: 591–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenberghe, Christian, Alexandra Panaccio, Kathleen Bentein, Karim Mignonac, and Patrice Roussel. 2011. Assessing longitudinal change of and dynamic relationships among role stressors, job attitudes, turnover intention, and well-being in neophyte newcomers. Journal of Organizational Behavior 32: 652–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, Pieter A., and Andrea Kirk Brown. 2006. Emotional labour and negative job outcomes: An evaluation of the mediating role of emotional dissonance. Journal of Management & Organization 12: 101–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Jaarsveld, Danielle, and Winifred R. Poster. 2013. Call centers: Emotional labor over the phone. In Emotional Labor in the 21st Century: Diverse Perspectives on Emotion Regulation at Work. Edited by Alicia A. Grandey, James M. Diefendorff and Deborah E. Rupp. New York: Routledge, pp. 153–73. [Google Scholar]

- Wegge, Jürgen, Rolf Van Dick, and Christiane Von Bernstorff. 2010. Emotional dissonance in call centre work. Journal of Managerial Psychology 25: 596–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegge, Jürgen, Joachim Vogt, and Christiane Wecking. 2007. Customer-induced stress in call centre work: A comparison of audio-and videoconference. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 80: 693–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workman, Michael, and William Bommer. 2004. Redesigning computer call center work: A longitudinal fields experiment. Jorunal of Organizational Behavior 25: 317–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Thomas A., and Russell Cropanzano. 1998. Emotional exhaustion as a predictor of job performance and voluntary turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology 83: 486–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zapf, Dieter, Amela Isic, Myriam Bechtoldt, and Patricia Blau. 2003. What is typical for call centre jobs? job characteristics and service interactions in different call centres. European Journal of Work amd Organizational Psychology 12: 311–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapf, Dieter, Claudia Seifert, Barbara Schmutte, Heidrun Mertini, and Melanie Holz. 2001. Emotion work and job stressors and their effects on burnout. Psychology & Health 16: 527–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapf, Dieter, Christoph Vogt, Claudia Seifert, Heidrun Mertini, and Amela Isic. 1999. Emotion work as a source of stress: The concept and the development of an instrument. European Journal of Work amd Organizational Psychology 8: 371–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).