Effects of the Entrepreneurial Strategic Orientation of Social Enterprises on Organizational Effectiveness: Case of South Korea

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Social Enterprises and Entrepreneurial Strategic Orientation

2.2. Entrepreneurial Strategic Orientation and Dynamic Capabilities

2.3. Dynamic Capabilities and Organizational Effectiveness

3. Research Method

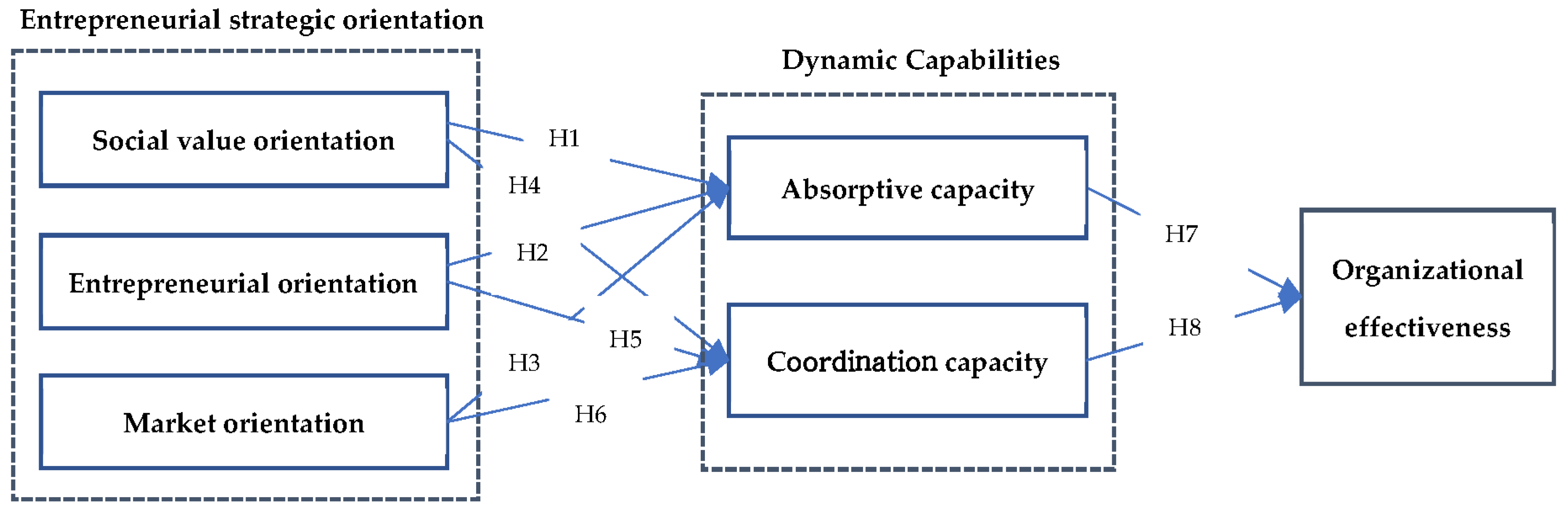

3.1. Research Model

3.2. Measurement Variable and Data Collection

3.3. Demographic Information of the Data

4. Results

4.1. Analysis Results of Reliability and Validity

4.2. Analysis Results of Structural Model

4.3. Analysis Results of Mediated Effect

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alter, Kim. 2007. Social enterprise typology. Virtue Ventures LLC 12: 1–124. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, James, Howard Stevenson, and Jane Wei-Skillern. 2006. Social and commercial entrepreneurship: Same, different, or both? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 30: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeem, Syed Mohammad. 2010. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment among employees in the Sultanate of Oman. Psychology 1: 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziri, Brikend. 2011. Job satisfaction: A literature review. Management Research & Practice 3: 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, Jay. 1991. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of management 17: 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battilana, Julie, and Silvia Dorado. 2010. Building sustainable hybrid organizations: The case of commercial microfinance organizations. Academy of Management Journal 53: 1419–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besharov, Marya L., and Wendy K. Smith. 2012. Multiple Logics within Organizations: An Integrative Framework and Model of Organizational Hybridity. Ithaca: Cornell University Working Paper. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattarai, Charan Raj, Caleb C. Y. Kwong, and Misagh Tasavori. 2019. Market orientation, market disruptiveness capability and social enterprise performance: An empirical study from the United Kingdom. Journal of Business Research 96: 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, Amnon, Eran Vigoda-Gadot, and Nurit Segev. 2011. Market orientation in social services: An empirical study of motivating and hindering factors among Israeli social workers. Administration in Social Work 35: 138–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, Harry, Joachim Kuhn, and Frank Gertsen. 2006. Continuous Innovation: Managing Dualities through Co-ordination. CINet Working Paper Series, WP2006-01. Available online: http://www.continuous-innovation.net/Publications/CINet)Publications.html (accessed on 16 November 2021).

- Brooke, Paul P., Daniel W. Russell, and James L. Price. 1988. Discriminant validation of measures of job satisfaction, job involvement, and organizational commitment. Journal of Applied Psychology 73: 139–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, William A., and Carlton F. Yoshioka. 2003. Mission attachment and satisfaction as factors in employee retention. Nonprofit Management and Leadership 14: 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, Mike, and Rory Ridley-Duff. 2019. Towards an appreciation of ethics in social enterprise business models. Journal of Business Ethics 159: 619–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, Kim. 2010. Five keys to flourishing in trying times. Leader to Leader 55: 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caringal-Go, Jaimee Felice, and Ma Regina M. Hechanova. 2018. Motivational needs and intent to stay of social enterprise workers. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 9: 200–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, Jeffrey, and Slevin Denni. 1989. Strategic management of small firms in hostile and benign environments. Strategic management journal 10: 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daft, Richard L. 2015. Organization Theory and Design. Boston: Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Defourny, Jacques, and Marthe Nyssens. 2010. Conceptions of social enterprise and social entrepreneurship in Europe and the United States: Convergences and divergences. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 1: 32–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defourny, Jacques, Marthe Nyssens, and Olivier Brolis. 2021. Testing social enterprise models across the world: Evidence from the international comparative social enterprise models (ICSEM) project. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 50: 420–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, Bob, Helen Haugh, and Fergus Lyon. 2014. Social enterprises as hybrid organizations: A review and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews 16: 417–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorado, Silvia. 2006. Social entrepreneurial ventures: Different values so different process of creation, no? Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship 11: 319–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchek, Stephanie. 2013. Capturing absorptive capacity: A critical review and future prospects. Schmalenbach Business Review 65: 312–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Abhishek, and Jay Weerawardena. 2018. Conceptualizing and operationalizing the social entrepreneurship construct. Journal of Business Research 86: 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, Kathleen M., and Jeffrey A. Martin. 2000. Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strategic Management Journal 21: 1105–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzioni, Amitai, and Paul R. Lawrence. 2016. Socio-Economics: Toward a New Synthesis. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gatignon, Hubert, and Jean-Marc Xuereb. 1997. Strategic orientation of the firm and new product performance. Journal of Marketing Research 34: 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassl, Wolfgang. 2012. Business models of social enterprise: A design approach to hybridity. ACRN Journal of Entrepreneurship Perspectives 1: 37–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hult, G. Tomas M., Charles C. Snow, and Destan Kandemir. 2003. The role of entrepreneurship in building cultural competitiveness in different organizational types. Journal of Management 29: 401–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynes, Briga. 2009. Growing the social enterprise–issues and challenges. Social Enterprise Journal 5: 114–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Hyun-Suk, and Eun-Gu Ji. 2021. A study of validity and development of the social value orientation scale of social enterprises. Social Economy & Policy Studies 11: 37–67. [Google Scholar]

- Jantunen, Ari, Kaisu Puumalainen, Sami Saarenketo, and Kalevi Kyläheiko. 2005. Entrepreneurial orientation, dynamic capabilities and international performance. Journal of International Entrepreneurship 3: 223–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Insik, Jae H. Pae, and Dongsheng Zhou. 2006. Antecedents and consequences of the strategic orientations in new product development: The case of Chinese manufacturers. Industrial Marketing Management 35: 348–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, Robert S., and David P. Norton. 2005. The balanced scorecard: Measures that drive performance. Harvard Business Review 83: 71–79. [Google Scholar]

- Keh, Hean Tat, Thi Tuyet Mai Nguyen, and Hwei Ping Ng. 2007. The effects of entrepreneurial orientation and marketing information on the performance of SMEs. Journal of Business Venturing 22: 592–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerlin, Janelle A. 2006. Social enterprise in the United States and Europe: Understanding and learning from the differences. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 17: 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Seok-Eun, and Jung-Wook Lee. 2007. Is mission attachment an effective management tool for employee retention? An empirical analysis of a nonprofit human services agency. Review of Public Personnel Administration 27: 227–48. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Soo-Young, Wang-Jin Yoo, and Sang-Jin Lee. 2014. An improvement of organizational effectiveness through the analysis of the relationship between entrepreneurship and dynamic capabilities in IT venture business. Journal of Society for e-Business Studies 19: 101–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kohli, Ajay K., and Bernard J. Jaworski. 1990. Market orientation: The construct, research propositions, and managerial implications. Journal of Marketing 54: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Social Enterprise Promotion Agency. 2021. Korea Social Economy. Seoul: KEPA. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Gordon, Sachiko Takeda, and Wai-Wai Ko. 2014. Strategic orientation and social enterprise performance. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 43: 480–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G. Tom, and Gregory G. Dess. 1996. Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Academy of Management Review 21: 135–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, Arvind, Sanjay Gosain, and Omar A. El Sawy. 2005. Absorptive capacity configurations in supply chains: Gearing for partner-enabled market knowledge creation. MIS Quarterly 29: 145–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, John P., and Natalie J. Allen. 1991. A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review 1: 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, John P., David J. Stanley, Lynne Herscovitch, and Laryssa Topolnytsky. 2002. Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior 61: 20–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, Morgan P., Martie-Louise Verreynne, and Belinda Luke. 2014. Social enterprises and the performance advantages of a Vincentian marketing orientation. Journal of Business Ethics 123: 549–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, Morgan P., Martie-Louise Verreynne, Belinda Luke, Roy Eversole, and Josephine Barracket. 2013. The relationship of entrepreneurial orientation, Vincentian values and economic and social performance in social enterprise. Review of Business 33: 91–102. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Danny. 1983. The correlates of entrepreneurship in three types of firms. Management Science 29: 770–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, Michael H., Justin W. Webb, and Rebecca J. Franklin. 2011. Understanding the manifestation of entrepreneurial orientation in the nonprofit context. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 35: 947–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, Michael H., Susan Coombes, Minet Schindehutte, and Jeffrey Allen. 2007. Antecedents and outcomes of entrepreneurial and market orientations in a non-profit context: Theoretical and empirical insights. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies 13: 12–39. [Google Scholar]

- Mowday, Richard T., Lyman W. Porter, and Richard M. Steers. 2013. Employee—Organization Linkages: The Psychology of Commitment, Absenteeism, and Turnover. Cambridge: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, Janet Y., Gerald Yong Gao, and Masaaki Kotabe. 2011. Market orientation and performance of export ventures: The process through marketing capabilities and competitive advantages. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 39: 252–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, Sang-Gyun, and Chen Tian. 2014. A Study on the Effects of Market and Technological Orientation of Manufacturing Companies upon Absorptive Capacities and Product Development Performance. Journal of the Korea Safety Management and Science 16: 263–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narver, John C., and Stanley F. Slater. 1990. The effect of a market orientation on business profitability. Journal of marketing 54: 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, Alex, and Albert Hyunbae Cho. 2006. Social Entrepreneurship: The Structuration of a Field. Social Entrepreneurship: New Models of Sustainable Social Change. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly, Charles A., and Michael L. Tushman. 2004. The ambidextrous organization. Harvard Business Review 82: 74–83. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, Christine. 1991. Strategic responses to institutional processes. Academy of Management Review 16: 145–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pache, Anne-Claire, and Filipe Santos. 2013. Inside the hybrid organization: Selective coupling as a response to competing institutional logics. Academy of Management Journal 56: 972–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, Paul A., and Omar A. El Sawy. 2011. Understanding the elusive black box of dynamic capabilities. Decision Sciences 42: 239–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, Mary. 2006. Growing pains: The sustainability of social enterprises. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation 7: 221–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetyo, Aries Heru, and Kim-Fatt Khiew. 2016. The Dynamic Capabilities of Social Enterprise: Explicating the Role of Antecedents and Unobserved Linkage. European Journal of Business and Management 8: 401–12. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, Filipe M. 2012. A positive theory of social entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Ethics 111: 335–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpello, Vida, and Robert J. Vandenberg. 1992. Generalizing the importance of occupational and career views to job satisfaction attitudes. Journal of Organizational Behavior 13: 125–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharir, Moshe, and Miri Lerner. 2006. Gauging the success of social ventures initiated by individual social entrepreneurs. Journal of World Business 41: 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, Stanley F., and John C. Narver. 1995. Market orientation and the learning organization. Journal of Marketing 59: 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, Stanley F., and John C. Narver. 2000. The positive effect of a market orientation on business profitability: A balanced replication. Journal of Business Research 48: 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soh, Jung-In. 2012. The Dynamics and Long-Term Stability of Social Enterprise: Patterns in Social Entrepreneurship Research. Northhampton: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Spector, Paul E. 1997. Job Satisfaction: Application, Assessment, Causes, and Consequences. New York: Sage Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Steers, Richard M. 1975. Problems in the measurement of organizational effectiveness. Administrative Science Quarterly 20: 546–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, David J. 2007. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strategic Management Journal 28: 1319–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, David J., Gary Pisano, and Amy Shuen. 1997. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal 18: 509–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenabeele, Wouter. 2009. The mediating effect of job satisfaction and organizational commitment on self-reported performance: More robust evidence of the PSM—Performance relationship. International Review of Administrative Sciences 75: 11–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vézina, Martine, Majdi Ben Selma, and Marie Claire Malo. 2019. Exploring the social innovation process in a large market based social enterprise: A dynamic capabilities approach. Management Decision 57: 1399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vittoria, M. Patrizia, and Pasquale Persico. 2010. Social Enterprise in Dynamic Capabilities Management Model. Naples: Stern School of Business. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Catherine L., and Pervaiz K. Ahmed. 2007. Dynamic capabilities: A review and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews 9: 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerawardena, Jay, and Gillian Sullivan Mort. 2006. Investigating social entrepreneurship: A multidimensional model. Journal of World Business 41: 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, Johan, and Dean Shepherd. 2003. Knowledge-based resources, entrepreneurial orientation, and the performance of small and medium-sized businesses. Strategic Management Journal 24: 1307–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Thomas A., and Russell Cropanzano. 1998. Emotional exhaustion as a predictor of job performance and voluntary turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology 83: 486–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, Dennis R., and Choony Kim. 2015. Can social enterprises remain sustainable and mission-focused? Applying resiliency theory. Social Enterprise Journal 11: 233–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, Shaker A., and Gerard George. 2002. Absorptive capacity: A review, reconceptualization, and extension. Academy of Management Review 27: 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, Shaker A., and Jeffrey G. Covin. 1995. Contextual influences on the corporate entrepreneurship-performance relationship: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Business Venturing 10: 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Kevin Zheng, and Caroline Bingxin Li. 2010. How strategic orientations influence the building of dynamic capability in emerging economies. Journal of Business Research 63: 224–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Kevin Zheng, Chi Kin Yim, and David K. Tse. 2005. The effects of strategic orientations on technology-and market-based breakthrough innovations. Journal of Marketing 69: 42–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors | Survey Items | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial strategic orientation | Social value orientation |

| Jang and Ji (2021), Miles et al. (2013), Sharir and Lerner (2006) |

| Entrepreneurial orientation |

| Miles et al. (2013), Covin and Slevin (1989) | |

| Market orientation |

| Narver and Slater (1990) | |

| Dynamic capabilities | Absorptive capacity |

| Pavlou and El Sawy (2011), Murray et al. (2011), Zahra and George (2002) |

| Coordination capacity |

| ||

| Organizational effectiveness |

| Vandenabeele (2009), Wright and Cropanzano (1998) | |

| Category | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 122 | 53.5 |

| Female | 106 | 46.5 | |

| Total | 228 | 100.0 | |

| Age | Younger than 30 | 8 | 3.5 |

| 30 to 40 | 48 | 21.1 | |

| 40 to 50 | 70 | 30.7 | |

| 50 or over | 102 | 44.7 | |

| Total | 228 | 100.0 | |

| Career (years) | 1 or less | 16 | 7.0 |

| 1 to less than 2 | 32 | 14.0 | |

| 3 to less than 5 | 38 | 16.7 | |

| 5 to less than 10 | 63 | 27.6 | |

| 10 to less than 15 | 35 | 15.4 | |

| 15 or more | 44 | 19.3 | |

| Total | 228 | 100.0 | |

| Position | Employee | 26 | 11.4 |

| Deputy Section Chief | 19 | 8.3 | |

| Middle Manager | 57 | 25.0 | |

| Executive | 126 | 55.3 | |

| Total | 228 | 100.0 | |

| Organizational type | Job offer | 133 | 58.3 |

| Social service offer | 25 | 11.0 | |

| Mixed | 17 | 7.5 | |

| Community contribution | 25 | 11.0 | |

| Others (creative, innovative) | 28 | 12.3 | |

| Total | 228 | 100.0 | |

| Size of company (employees) | 10 or less | 113 | 49.6 |

| 11–20 | 48 | 21.1 | |

| 21–50 | 37 | 16.2 | |

| 51–100 | 7 | 3.1 | |

| Over 100 | 23 | 10.1 | |

| Total | 228 | 100.0 | |

| Variable | Standard Factor Loading | Standard Deviation | t Value (p) | CR | AVE | Cronbach’s α | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social value orientation | SV_1 | 0.804 | 0.821 | 0.605 | 0.819 | ||

| SV_2 | 0.763 | 0.089 | 11.195 *** | ||||

| SV_3 | 0.765 | 0.086 | 11.228 *** | ||||

| Entrepreneurial orientation | EO_1 | 0.807 | 0.891 | 0.622 | 0.889 | ||

| EO_2 | 0.723 | 0.090 | 11.763 *** | ||||

| EO_3 | 0.881 | 0.082 | 15.213 *** | ||||

| Market orientation | MO_1 | 0.676 | 0.859 | 0.605 | 0.855 | ||

| MO_2 | 0.788 | 0.122 | 10.400 *** | ||||

| MO_3 | 0.810 | 0.125 | 10.636 *** | ||||

| Absorptive capacity | AC_1 | 0.662 | 0.771 | 0.530 | 0.770 | ||

| AC_2 | 0.758 | 0.100 | 9.592 *** | ||||

| AC_3 | 0.760 | 0.099 | 9.606 *** | ||||

| Coordination capacity | CC_1 | 0.840 | 0.901 | 0.752 | 0.898 | ||

| CC_2 | 0.871 | 0.059 | 16.132 *** | ||||

| CC_3 | 0.889 | 0.057 | 16.584 *** | ||||

| Organizational effectiveness | OE_1 | 0.730 | 0.714 | 0.555 | 0.714 | ||

| OE_2 | 0.760 | 0.103 | 8.447 *** | ||||

| Category | AVE | SV | EO | MO | AC | CC | OE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social value orientation (SV) | 0.605 | 0.778 | |||||

| Entrepreneurial orientation (EO) | 0.622 | 0.566 | 0.789 | ||||

| Market orientation (MO) | 0.605 | 0.491 | 0.610 | 0.778 | |||

| Absorptive capacity (AC) | 0.530 | 0.429 | 0.579 | 0.668 | 0.728 | ||

| Coordination capacity (CC) | 0.752 | 0.492 | 0.551 | 0.602 | 0.649 | 0.867 | |

| Organizational effectiveness (OE) | 0.555 | 0.413 | 0.402 | 0.505 | 0.439 | 0.541 | 0.745 |

| Hypothesis (Path) | Standard Path Coefficient | t Value | Status of Adoption | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Social value orientation -> Absorptive capacity | 0.036 | 0.432 | Rejected | 0.549 |

| H2 | Entrepreneurial orientation -> Absorptive capacity | 0.224 | 2.389 * | Adopted | |

| H3 | Market orientation -> Absorptive capacity | 0.692 | 6.345 *** | Adopted | |

| H4 | Social value orientation -> Coordination capacity | 0.216 | 2.520 * | Adopted | 0.777 |

| H5 | Entrepreneurial orientation -> Coordination capacity | 0.165 | 1.768 | Rejected | |

| H6 | Market orientation -> Coordination capacity | 0.463 | 5.057 *** | Adopted | |

| H7 | Absorptive capacity -> Organizational effectiveness | 0.277 | 2.659 ** | Adopted | 0.507 |

| H8 | Coordination capacity -> Organizational effectiveness | 0.502 | 4.778 *** | Adopted |

| Dependent Variable | Explanatory Variable | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Total Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational effectiveness | Absorptive capacity | 0.277 | - | 0.227 |

| Social value orientation | - | 0.010 | 0.010 | |

| Entrepreneurial orientation | - | 0.062 | 0.062 | |

| Market orientation | - | 0.192 | 0.192 | |

| Coordination capacity | 0.502 | - | 0.502 | |

| Social value orientation | - | 0.108 * | 0.108 | |

| Entrepreneurial orientation | - | 0.083 ** | 0.083 | |

| Market orientation | - | 0.232 *** | 0.232 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cho, C.; Kim, B.; Oh, S. Effects of the Entrepreneurial Strategic Orientation of Social Enterprises on Organizational Effectiveness: Case of South Korea. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12010019

Cho C, Kim B, Oh S. Effects of the Entrepreneurial Strategic Orientation of Social Enterprises on Organizational Effectiveness: Case of South Korea. Administrative Sciences. 2022; 12(1):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12010019

Chicago/Turabian StyleCho, Changwon, Boyoung Kim, and Sungho Oh. 2022. "Effects of the Entrepreneurial Strategic Orientation of Social Enterprises on Organizational Effectiveness: Case of South Korea" Administrative Sciences 12, no. 1: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12010019

APA StyleCho, C., Kim, B., & Oh, S. (2022). Effects of the Entrepreneurial Strategic Orientation of Social Enterprises on Organizational Effectiveness: Case of South Korea. Administrative Sciences, 12(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12010019

_김_(김).png)