Abstract

Educational needs are changing worldwide. Social aspects and the impact of knowledge and education on changing society are already taken into consideration from some viewpoints. However, the social impact of different models of education that bring new knowledge in innovative ways and the application of social entrepreneurship still need be investigated. The main question that this study addressed is how higher education institutions (HEIs) will approach the new era, in relation to knowledge needs and their social impact, and which model allows HEIs to become more entrepreneurial and follow social entrepreneurship. The paper contributes to addressing challenges and opportunities that universities (especially those located in developing countries) face in their pathway to developing social entrepreneurship education with the aim of increasing their value creation capacity. Through a case study analysis, this paper highlights the relevance of knowledge creation, circulation, and transfer among different stakeholders for universities to shift towards an entrepreneurial and innovative perspective. The findings of this research highlight the relevance of social innovation, knowledge development processes, and wide and collaborative national and international networks as essential elements in paving the way for universities to become entrepreneurial universities.

1. Introduction

A new era of higher education is underway. To understand the future, business schools of HEIs need to understand tomorrow’s student. Studies show that, as there is still a category of students who think they will work as their parents did in the 1970s, most of them think that at least once they will change their career completely in their lifetime, while there are others that think they will start working for themselves (Clark 2001). Students with these points of view will need to learn throughout their lifetime, update their skills, and add new skills as their careers demand. Since knowledge is an intangible resource that can empower products/services/processes, lately emphasis has been placed on addressing increased attention to societal challenges and social innovation in this context (Chiva et al. 2014). The concept of social innovation (Ndou and Schiuma 2020) deals with creating and applying new knowledge that supports the solution of social problems from all stakeholders through products/services that can better serve local communities. Social issues are increasingly common in the context of HEIs and society, not only in public but also private institutions, and not only in their overall institutional behavior but also especially in some traditional schools and faculties such as business schools/faculties. Professor Clayton Christensen of Harvard Business School, in reporting his thoughts with regard to the new era of HEIs, says: “I think higher education is just on the edge of the crevasse. Generally, universities are doing very well financially, so they do not feel from the data that their world is going to collapse. But I think even five years from now these enterprises are going to be in real trouble.”

The ability of HEIs to predict education trends for specific types of education and education methodologies, etc., is very important for the anticipation of these changes (Altbach et al. 2009) to capture the market opportunities more accurately and for aligning them with the predictions of global demand for education, skills, and knowledge (Barnett 2000, 2005). The social impact of these trends needs to be taken into consideration through the intertwining nature of social innovation and knowledge-based development because of the need for knowledge to make social innovation happen (Schiuma and Lerro 2014). According to Yigitcanlar (2019), capturing and predicting the emerging needs of society for social change is impacted by the implementation of knowledge in actions related to the field. In higher education institutions, the results of many studies show how an intensifying appetite for more knowledge that will sustain business and industries is re-writing the rules of business education, changing the mindset of learners when it comes to how they study and what they study towards.

In these conditions, HEIs in general and specifically business schools within them, which can serve as leaders in many entrepreneurial processes in society, need to find how to leverage their continuing brand strengths and their tangible and intangible assets to retain a central role in extended learning lives (Ndou et al. 2019). Many authors have dedicated their research to the relationship between knowledge and social innovation, as well as skills and education, but there is still a need to deepen the study of institutional aspects in HEIs. In this regard there is a gap in studies on how this could be achieved within a new model of entrepreneurial education that also leads to social improvements within society and communities.

The paper presents the authors’ contributions to finding relationships between concepts such development, knowledge, skills, and social innovation. Business and tourism industry environments are taken as illustrations of skills and knowledge needs to contribute to socioeconomic development and the role of social innovation. A case study of University of Tirana, as the biggest university in Albania and one of the most important in the Western Balkans, is considered to contribute a proposal of a new model of education provision through social innovation.

2. Literature Review

There is a considerable discussion about the difference between administrative or traditional education and entrepreneurial education (Barnett 2000, 2005; Jongbloed 2008). According to Conceição et al. (2003), fostering innovation in a learning society requires institutions to pay attention to strategies and growth from knowledge resources. In particular, those discussions are followed up by the effect of COVID-19 in transforming the methods of educating based on changing needs for skills, knowledge, and competencies. With regard to experiential courses such as those including entrepreneurship learning, the COVID-19 pandemic poses a significant challenge to management education (Brammer and Clark 2020; Kryukov and Gorin 2017). Traditional business education models were built for a world in which learning was frontloaded. Degrees were earned on campus in a single period of up to four years, and this time commitment meant that most students earned them before entering the workplace (Gorica et al. 2019). They would then depend on this bank of learning to see them through their careers, perhaps with the addition of a one- or two-year postgraduate degree in their late 20s/early 30s (Altbach et al. 2009; Carringtoncrisp and LinkedIn Report 2020). On the other hand, social innovation proposes inclusive learning which, together with social capital, impacts the distributed knowledge that brings growth and is therefore considered a crucial element for local development (Moulaert and Nussbaumer 2005).

On the other hand, at a time when professionals expect to update skills and switch careers several times in their working life (Secundo et al. 2019), it seems like an increasingly risky approach to invest in knowledge. Even after the COVID-19 crisis, universities will have to deal with the urgent need to reconfigure traditional programs using digital technologies (Giustina et al. 2021).

Lifelong learning is the logical response to an era in which people expect to work for longer—and expect regular disruption to the business landscape during that time (Estermann and Claeys-Kulik 2013). Thus, even the education method is no longer based on the traditional model (Barnett 2005). This means that 3 or 4 years of a strong bachelor is no longer sufficient. Markets will continuously need new approaches on knowledge, new skills, and new means of supplying those skills, which will be provided through lifelong learning courses or several educational offers. For this purpose, including the different actors in the field for gaining knowledge, especially those actors that generate novelty (Shattock 2006), will contribute to bettering knowledge with local and external sources and will underline the differences related to the degree of innovative actors’ interaction within a local network (Gibb and Haskins 2013). The study of Shattock (2005) analyzes the innovation systems (milieu) for innovation-oriented development, focusing the investigation on the role of knowledge-based environment, cooperation among actors, and networking for developing an innovative milieu. A final fact to be evaluated is that new generations are feeling more comfortable and secure with more diplomas, and also several mixed diplomas are requested in order to adapt education to changes of market requirement for skills and knowledge (Ndou et al. 2018b).

For example, one industry with a new strategy for knowledge and education after COVID-19 is tourism because millions of jobs were sacrificed or put in danger. Not only jobs but the tourism ecosystem in Europe and worldwide has been jeopardized due to the COVID-19 crisis (Tiwari et al. 2020). It is in times of crisis that business, jobs, employment, and community connect in the short term and postpone investment in the long term (Ndou et al. 2018b). However, long-term solutions require agreement among all the actors, and tourism was an example of this during the crisis. Since it is an industry related to destinations, sustainable development, and to people, the knowledge component and the social component are very important to finding common points among actors. Ndou and Schiuma (2020) in their study identify three research streams with growing importance related to social innovation and knowledge impact on local development, one of which is the dynamics of social innovation for territorial development. They found some of the most significant contributions that relate these subjects, e.g., Gertler and Levitte (2005), who focus on internal resources and firm capabilities as well as local and global flows of knowledge, which determine innovation, and Carson et al. (2014), whose focus is on tourism industry through analyses of stakeholders and the contribution of communities to innovation at a regional level, though encountering significant barriers and through them the inability to stimulate knowledge sharing and transfer (Ndou et al. 2018a).

Regarding tourism, employment in this sector includes many professions from managers of tourism units, product managers, and brand marketing to intermediate levels of management of various sub-sectors and simple employees. All these categories and levels of professions need to be reoriented and supplied with the necessary knowledge, skills, and competencies, which should be provided by universities through updated or entirely new qualitative curricula.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Project Design

The methodology used for this study is based on a bottom-up model, which means first of all using the model of an entrepreneurial university to identify members of the community from which information on perceptions and opinions is gathered. All-important stakeholders that the model identifies are considered as a strong source of information in order to give a fully social entrepreneurial concept of a university. Both quantitative and qualitative methods were used to gather and analyze the data.

Qualitative methods were used, involving a detailed desk research of literature, reports, documents, publications, government strategies, and recent important events (forums, conferences, etc.) directly or indirectly linked to the entrepreneurial university concept as well as 15 interviews of important stakeholders to gather information from public and private actors that are directly related to universities, especially UT.

A quantitative method was designed to gather data from students and professors as well as university leaders and administrators at the University of Tirana.

3.2. Research Instruments

The research instruments used were interviews and questionnaires.

The interviews were directed to stakeholders to identify information related to their perception of UT value and positioning, perception on opportunities for value cocreation, and their role related to improving knowledge through innovative models and collaboration.

The questionnaire was divided into several parts, comprising the following information: different used methods of learning/teaching perceived as innovative and entrepreneurial inside the institution and projects with emphasis on entrepreneurship and innovation in related fields of study.

3.3. Place and Participant Recruitment

The main criteria for stakeholder selection are that everybody related to knowledge management and the entrepreneurial social university is a crucial stakeholder for UT. Interviewees were contacted through a list of related institutions. In-depth interviews were organized with:

- Experts in the Ministry of Education.

- Project managers and experts in social innovation knowledge, education, and training in different NGOs/international projects.

- Individual national experts located in Tirana related to innovation and entrepreneurial projects related to higher education.

- Experts on human resources and employment in businesses environments.

They were contacted by email and required to give information about the issues mentioned above. The second round of emails sent to the experts who demonstrated a very active and collaborative attitude during the first phases requested a face-to-face interview to obtain more detailed information on certain issues

Questionnaires on the other hand were sent online and replied to by 165 students, 17 leaders/administrators in UT, and 87 university teachers of different faculties.

3.4. Data Analysis

The data were analyzed through two main methods. Text analyses were used for interviews to identify the main aspects that relate the positioning and value of UT curricula and courses with the opportunities to collaborate and cocreate with stakeholders (institutions organizations, business leaders, experts, services) and with the social innovation models used. Second, quantitative analyses related to questionnaires were used to discover possible relations between variables such as marketing plan elements, product/offer/curricula elements, branding elements, and market relations.

4. Results

4.1. New Education Challenges for Traditional HEI Institutions: The Case of the University of Tirana

Too often HEIs have a traditional approach more or less guided by their business schools that are product-centered when the contemporary HEIs and schools need to be more decentralized and flexible. The challenges faced by universities in the Balkans, and especially the University of Tirana, are numerous, different, and difficult.

The University of Tirana, as a well-known brand in the higher education area according to the national report and strategy on higher education, has the potential to leverage its existing strengths through new partnerships—creating blended and distinctive experiences that can meet the varied needs of lifelong learners. This is identified not only in the reports and desk research as a simple recommendation but especially in the analysis of interviews as a challenge for UT, which needs to make every effort to fulfill its value proposition challenge to be entrepreneurial. One of the main challenges of UT as expressed by stakeholders, especially NGO/project representatives and external experts, is related to internationalization. The interviews resulted in identification of main areas where the University of Tirana will need to become more involved in cocreating a value proposition with students, businesses, investors, stakeholders, and administrative and academic staff, with better internationalization as its main challenge. One of the most common answers to the question related to actions for creating knowledge and social innovation inclusion is the involvement of social aspects in its brand concept and advice to relate market needs with appropriate plans and products, including innovative ways to create curricula and skills towards knowledge creation. The creation of educational products for more innovative knowledge, skills, and competencies is seen as a challenge by all stakeholders. Relationships with schools related to business and economy are highlighted from stakeholders more than in other cases.

The University of Tirana (TU) is the largest University in Albania and includes six faculties. Based on a study (Gorica and Cojoaca 2016), dimensions that are seen as most important among academics engaging in the public institutions of HEIs in Albania, are proactivity and value creation, while the least important are the focus on opportunities and innovation. The marketing applied to public institutions of higher education in Albania is traditional marketing, which focuses more on the relationship of transaction, while the application of the entrepreneurial model in marketing focuses on innovation and self-orientation towards the creation value. According to the quantitative study and the measurement of weighed averages, we found that university involvement in socioeconomic development is weak, and educational institutions are “designated as educational and research institutions but are limited only in learning” and are less flexible according to a participant in the study. The respondents claim that they are proactive in influencing the environment of the organization. Education is becoming more interactive and flexible, communication more immediate and interactive, and research (at least) more cooperative and open. The relationship of the universities with local business and industry is weak; no respondents reported any assertion that universities may have prompted or influenced the establishment of a new business or related innovation activities or support new venture or any entrepreneurial start-up activity.

4.2. Higher Education Market Equilibrium Is Difficult to Be Achieved

Based on the characteristics of the University of Tirana and referring specifically to departments within one of the six faculties (Faculty of Economy- FEUT), since it is mentioned as more related to the stakeholders, business environment, and public administration, we analyzed and co-discussed the reasons for a general and common problem for the University of Tirana, the difficulty in achieving Higher Education market equilibrium:

- From one side, change and evolution of market needs for more and diversified capabilities, skills, and capacities have impacted the emergence of different markets, business needs changes, and more multidisciplinarity, representing almost a revolution in needs for diplomas and types of diploma, which means that is very difficult to survey to market if HEIs cannot equilibrate the market;

- From the other side, the education market is always subject to change, and its stakeholders need to search and conduct market research to achieve equilibrium (Gibb 2013). Demand of the education market is very elastic; this not the case for supply because to improve, change, and adapt curricula requires time and capabilities as well as cooperation and strong networking with businesses and public institutions that interact directly with the education market. Thus, a regulatory system needs to manage the higher education market equilibrium (Gibb et al. 2012).

Within the University of Tirana, regarding the above analyses, the Faculty of Economy is one step ahead due to the coherence that results from all activities that the Faculty of Economics, University of Tirana (FEUT) has demonstrated in recent decades. Recently, however, private universities, due to a lack of autocratic administrative rules, have made advances in infrastructure and technology. For many reasons, FEUT needs to re-dimension and adapt to the education market with new and flexible curricula. This is a must, as recently shown by several studies undertaken by academics within FEUT with the aim of moderating curricula based on market orientation (MO) and entrepreneurial orientation (EO) in the internationalization platform.

4.3. Proposing a New Model for Repositioning the University of Tirana for Better Internationalization

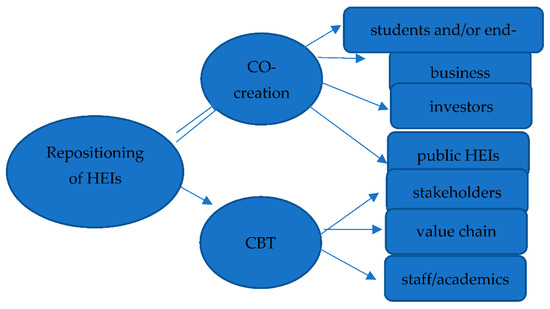

The results of the stakeholder study are shown in Figure 1. The main philosophy that describes the need for of this new positioning is based on:

Figure 1.

A new model of repositioning of UT within the internationalization framework.

- The main principle and need for internationalization;

- The strength of the brand on the market.

In the main framework of internationalization, the University of Tirana as a very strong brand needs to reorganize its strength into repositioning. Some aspects of this model are as follows:

Students, who can be considered as the main and final customers, benefit from every teaching product/service offered by UT (CBT). The diversification of the offer of products and services that UT should offer in all its basic units (departments) should aid student satisfaction. Thus, even after obtaining a bachelor’s degree, a student, thanks to the brand and good name of the HEI, as well as the faculty, will return to enroll in another course or suggest the institution to friends and relatives. Thus, alumni can provide feedback on how existing UT products can be improved or what other products on the market suggest.

On the other hand, the largest businesses in Albania are currently supplied with human resources by the Faculty of Economics, University of Tirana (Gorica and Kordha 2020). FEUT’s academic staff are currently serving with the knowledge that skills and capabilities imparted to current students will prove important in the future market, which will cocreate future products that will serve the re-positioning of UT with the aim of creating a proposed superior value that will serve not only the delivery of products but the increase of UT’s capital and market share and strengthening of the university image (Kripa and Gorica 2020). This process will continue and be reshaped by improving through feedback and approaching the final goal: internationalization and strengthening of the UT brand.

4.4. Investors and Other Stakeholders, Part of the Value Chain

Different studies relate the need for interaction between the business environment and educational institutions (Bateman and Crant 1993). Angelstam et al. (2011) focus their study on the importance of social learning processes based on local actors and the need to produce innovative knowledge including these actors. Improved collaboration of stakeholders from different levels and sectors is one of their suggestions for achieving governance and management in European landscapes, related to relevance of transdisciplinary knowledge production and the collaborative learning process. Regarding stakeholders and actors in HEIs, it can be seen from the interviews that the interests of large businesses are consequently strongly linked to higher education and the quality of product created by them. It is not uncommon for firms that are strongly oriented towards a specific field to connect and attract specialized human resources from a HEI (Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff 2000b). Thus, for example, the large number of businesses related to the construction and management of a tourist location with more than four stars may require that they rely on the Faculty of Economics, UT. Thus, based on the two theories of cocreation and community (bottom-up), specialized curricula (products/services) can be created especially for these businesses (Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff 2000a). These can be LLCs, 2-year or 6-month courses, specific training, intensive modules, or other diplomas. Thus capital, brands, market share, and opportunities for internationalization increase greatly for UT.

People and human resources include academic staff, professors and new applicants within UT, administrative staff, and support offices within UT administration. All staff create and support the product created in collaboration with other actors in the value chain and obtained through the bottom-up model. Thus, following the example above, the UT’s departments may engage in cocreating an LLC with important businesses in Albania, and some staff may have ideas and become more actively involved in improvements and suggestions that increase the quality of service provided. Through this bottom-up philosophy, not only are the economic and financial interests of staff fulfilled, but more opportunities for creating knowledge through social innovation practices also arise.

5. Discussion

The University of Tirana in Albania is one of the oldest and important universities in the Balkan area, and this is one of the reasons why in several studies we compare the international educational challenge within the Balkan context, specifically HEIs in Albania and especially the University of Tirana. Thus, this prolonged discussion is related to several guidelines: what is going to be transformed in University of Tirana and how, and what exactly can be used as guidelines for our University in the Balkan context.

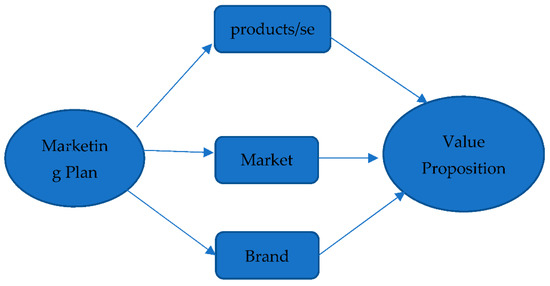

The two theories of cocreation and bottom-up (through the community-based approach) can be integrated to build the value of a HEI’s output through the elements related to innovation (Morgan 2017), value cocreation of knowledge, skills, and market demand and socioeconomic development. To finalize improvements in HEIs, business schools or economic faculties can lead the processes, since they are aware of market needs and business and entrepreneurial environments, thus leading the use of innovative methods in education. This process was included in the case of the University of Tirana along with the identification and construction of a proposed value for all actors and also the construction and development of marketing plans that support and enable the whole process. As the goal is to internationalize UT by strengthening its brand, and just as internationalization is directly related to the value proposition for all actors, a marketing plan and a simple traditional business perspective is not the right approach. Multiple efforts to improve the product (curricula) through social innovation and new methods of knowledge development as well as branding through networks and collaboration and value cocreation must be in place to fill all the elements of a new model. Specification and developed marketing plans for investors, employees within UT, and actors of the entire value chain whose needs must be met must be developed through this process.

Each of these stakeholders is concerned about product positioning to the end consumer and segmentation, but they are also concerned about other issues that are at least as important as the first—social capital and the image of the venture, for the communities and society.

Ultimately this will lead to a positioning model, which in addition to internationalization will also directly affect:

- A variety of innovative products/services, ultimately resulting in a deeper sense of proactivity, opportunity, and social innovation;

- The increase of UT’s capital, thus increasing the financial strength of UT, keeping it closer and including the business financially in the market share, and strengthening the proposed value as it makes UT strongly oriented by the market and entrepreneurial;

- The image of the university through this powerful network created.

All these results can help the University of Tirana in its endeavor to move “easily” from being traditional to being entrepreneurial and innovative, thus impacting development through knowledge. This is evident with an active approach to some of the elements identified and included throughout this journey: proactivity, value-based proposal, opportunity, customer intensity, and driven by opportunities, as seen in Figure 2. As a result of this journey, the University of Tirana, in addition to the safe path towards internationalization and strengthening the brand, will be even more inclined in the future towards some other elements that will make it even more entrepreneurial. These other elements will be a consequence of this process and will become daily practices of UT, i.e., focusing on social innovation, risk management or resource leveraging, and knowledge and market need focuses for development.

Figure 2.

Value proposition development of UT.

Thus, this new type of management and marketing attitude held by the University of Tirana will enable the following for the future:

- Foundations for great benefits: the discovery of fast techniques for positioning, targeting, and segmentation.

- An entrepreneurial attitude, culture and management to all marketing functions; performs and predominates entrepreneurial awards, promotion, including employment. Provides an entrepreneurial power for distribution, promotion, etc.

- Maximization of the value of all stakeholder relationships and benefits through marketing to investors, brokers, employees, partners, and users.

- Improved product ideas or innovative education services.

- New products to maximize profitability from their life cycle.

- Marketing based on what really works and maximization of marketing investment by striving for community and society benefits.

6. Conclusions

In the face of these facts, HEIs in the European area, but mostly in the Balkans, face many challenges:

- Analyzing as soon as possible their current situation of education, curricula, and what HEIs are offering.

- Understanding that many changes are underway, with one certainty: The future will require HEIs to change and stay away from traditional models; to find opportunities to serve new and different segments, with various products; and to offer not only LLC courses but also interdisciplinary degrees. Being entrepreneurial and innovative means that offering interdisciplinary degrees is a safe way to grow the network but also to have safe new categories of students outside the HEI’s profile.

- Strengthening the brand of HEIs like University of Tirana, or those which have a successful history in Balkan Countries, which can be accomplished by:

- (a)

- Being proactive in bundle offers (products);

- (b)

- Considering brand strengthening strategies that lead to a safe internationalization path;

- (c)

- Working closely with business communities for an enlargement of capital (of HEIs) and strong market share;

- (d)

- ocusing on social innovation and knowledge for sustainable development.

To summarize and conclude, we must say that the qualitative, necessary, and rapid internationalization of UT is based especially on the repositioning theory, which is directly related to the benefits and consequences for stakeholders from administration, organizations, projects, businesses, and students. Further, this theory should be not only all inclusive but based on bottom-up theory and lastly lead to the identification of the proposed value that carries the key attributes and benefits that are enabled.

Mindset for Internationalization of UT

- A.

- All elements count

- In case of UT, experience in the market and the inheritance of supply in programs is an important element to create the brand. Changes from 4-year diplomas through bachelor and master’s degrees require a new mindset, but based on the value of the old brand, this needs internationalization, which needs innovative approaches to knowledge. Sometimes a business mindset can help towards the development, and business schools can lead the process but with a focus on entrepreneurial aspects of management and marketing plans and product/service development inside HEIs. UT has kept active the approach of product differentiation and positioning through lifelong learning courses, involvement in several projects based on the principle of internationalization, and being proactive. A new approach to marketing within the whole university, organizing open meetings with businesses, students and professors, with a clear strategic view of internationalization of departments and programs has helped in making small but sure steps forward.

- B.

- All inclusive of blended model of education is closer to business needs

For HEIs like the University of Tirana that are moving towards a new model of education, there is need to integrate innovative learning methods. Learning is not just about qualification and career enhancements but a blended or all-inclusive learning integrated experience. This can be a good opportunity for UT since the COVID-19 situation implies a new strategy of learning, including social innovation through digital media.

In order to strengthen its brand, the University of Tirana need to summarize all the above processes by identifying clean and distinctive values, entering partnerships and avoiding isolation, always utilizing bottom-up and cocreation theory to have a purpose and a focus on the purpose, and orienting its research towards a flexible approach.

- C.

- Efficient networking for a better partnership within and among Western Balkan Countries WBC

This means that the University of Tirana will have the possibility to cocreate its model or partnership, working closely and choosing only those businesses that have innovative ideas for the market in the future.

Limitations of the study

This study has its limitations related to the situation in the region. The study does not compare the facts gathered for UT with other Western Balkan HEIs, but the University of Tirana is trying on the other hand to internationalize, so the HEIs in other countries with similar opportunities and limitations are important to consider in future studies. The methodology of the study encountered a relatively high nonresponse rate in the target group of university teachers and administration. The non-responders were substituted to meet the appropriate sample size evaluation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.K.; methodology, K.G.; software, E.K.; validation, E.L.; formal analysis, D.K.; investigation, K.G. and E.K.; resources, E.L.; data curation, E.K.; writing—original draft preparation, K.G.; writing—review and editing, D.K. and E.K.; supervision, E.L.; project administration, E.K.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Altbach, Philip G., Liz Reisberg, and Laura E. Rumbley. 2009. Trends in Global Higher Education: Tracking an Academic Revolution. Available online: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0018/001831/183168e.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Angelstam, Per, Robert Axelsson, Marine Elbakidze, Lars Laestadius, Marius Lazdinis, Mats Nordberg, Ileana Pătru-Stupariu, and Mike Smith. 2011. Knowledge production and learning for sustainable forest management on the ground: Pan-European landscapes as a time machine. Forestry 84: 581–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barnett, Ronald. 2000. University knowledge in an age of super complexity. Higher Education 40: 409–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, Ronald. 2005. Convergence in Higher Education: The Strange Case of “Entrepreneurialism”. Higher Education Management and Policy 17: 51–64. Available online: http://www.oecd.org-/edu/imhe/42348745.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Bateman, Thomas S., and J. Michael Crant. 1993. The proactive component of organizational behavior: A measure and correlates. Journal of Organizational Behavior 14: 103–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, Steve, and Timothy Clark. 2020. COVID-19 and management education: Reflections on challenges, opportunities, and potential futures. British Journal of Management 31: 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carringtoncrisp and LinkedIn Report. 2020. A New Era of Higher Education. Available online: https://www.carringtoncrisp.com/intelligence/a-new-era-for-higher-education/ (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Carson, Doris Anna, Dean Bradley Carson, and Heidi Hodge. 2014. Understanding local innovation systems in peripheral tourism destinations. Tourism Geographies 16: 457–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiva, Ricardo, Pervez Ghauri, and Joaquín Alegre. 2014. Organizational learning, innovation and internationalization: A complex system model. British Journal of Management 25: 687–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, Burton. 2001. The Entrepreneurial University: New Foundations for Collegiality, Autonomy, and Achievement. Higher Education Management 13: 9–24. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/edu/imhe/37446098.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Conceição, Pedro, Manuel V. Heitor, and Francisco Veloso. 2003. Infrastructures, incentives, and institutions: Fostering distributed knowledge bases for the learning society. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 70: 583–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estermann, Thomas, and Anna-Lena Claeys-Kulik. 2013. Financially Sustainable Universities Full Costing: Progress and Practice. Brussels: European University Association, Available online: http://www.eua.be/Libraries/Publications_homepage_-list/Full_Costing_Progress_and_Practice_web.sflb.ashx (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Etzkowitz, Henry, and Loet Leydesdorff. 2000a. The dynamics of innovation: From National Systems and ‘‘Mode 2” to a Triple Helix of university–industry–government relations. Research Policy 29: 109–23. Available online: http://www.uni-klu.ac.at/wiho/downloads/Etzk.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2021). [CrossRef]

- Etzkowitz, Henry, and Loet Leydesdorff. 2000b. The Triple Helix of University-Industry-Government Relations. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam School of Communication Research (ASCoR). [Google Scholar]

- Gertler, Meric S., and Yael M. Levitte. 2005. Local nodes in global networks: The geography of knowledge flows in biotechnology innovation. Industry and Innovation 12: 487–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, Allan A. 2013. Developing the Entrepreneurial University of the Future. Key Challenges, Opportunities and Responses. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Gibb, Allan A., and Gay Haskins. 2013. The Entrepreneurial University: From Concept to Action. New York: NCEE, Available online: http://ncee.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/From-Concept-To-Action.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Gibb, Allan, Gay Haskins, and Ian Robertson. 2012. Leading the Entrepreneurial University, Meeting the Entrepreneurial Development Needs of Higher Education Institutions; New York: National Centre for Entrepreneurship in Education (NCEE). Available online: http://ncee.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/EULP-LEADERS-PAPER.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Giustina, Secundo, Mele Gioconda, Pasquale Del Vecchio, Elia Gianluca, Margherita Alessandro, and Ndou Valentina. 2021. Threat or opportunity? A case study of digital-enabled redesign of entrepreneurship education in the COVID-19 emergency. Technological Forecasting & Social Change 166: 120565. [Google Scholar]

- Gorica, Klodiana, and Ermelinda Kordha. 2020. New Digital Technologies Sustaining a Crucial Formation for Future Tourism Education—Implications for Professionals, Curricula, and Capabilities for HEIs. Paper presented at Challenges and Opportunities of a Contemporary Economy in the Focus of Knowledge and Science, International Conference of Faculty of Economy, University of Tirana, Tirana, Albania, February 27. [Google Scholar]

- Gorica, Klodiana, Kozeta Sevrani, Ermelinda Kordha, and Dorina Kripa. 2019. Orientation of university education towards the needs of the labor market in the Balkans—The role of IT and tourism as an interdisciplinary curricula’s. Paper presented at 8th International Conference on Business, Technology and Innovation, Lipjan, Kosovo, October 26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Gorica, Klodiana, and Ina Cojoaca. 2016. Towards Entrepreneurial Marketing: Why there is a need for higher Education Institutions to become Entrepreneurial, a Case of Public Universities in Albania. Journal of Educational Leadership and Policy 1: 1–6. Available online: http://www.aiscience.org/journal/paperInfo/jelp?paperId=2764 (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- Jongbloed, Ben. 2008. Funding Higher Education, a View across Europe. Enschede: Center for Higher Education and Policy Studies (CHEPS), University of Twente, Available online: http://www.utwente.nl-/bms/cheps/publications/Publications%202010/MODERN_Funding_Report.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- Kripa, Dorina, and Klodiana Gorica. 2020. Towards an entrepreneurial education approach of Universities in WBC. Paper presented at COST SHIINE Action 18236 “Multiply Disciplinary Innovation for Social Change”, International IFKAD 2020 Conference Knowledge in Digital Age, 15th Edition of the International Forum on Knowledge Asset Dynamics, Matera, Italy, September 9–11; Available online: https://www.ifkad.org (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- Kryukov, Vladimir, and Alexey Gorin. 2017. Digital technologies as education innovation at universities. Journal of Internet Banking and Commerce 32: 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, Clara. 2017. Constructing educational quality in the Arab region: A bottom-up critique of regional educational governance. Globalisation, Societies and Education 15: 499–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulaert, Frank, and Jacques Nussbaumer. 2005. The social region: Beyond the territorial dynamics of the learning economy. European Urban and Regional Studies 12: 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndou, Valentina, and Giovanni Schiuma. 2020. The role of social innovation for a knowledge-based local development: Insights from the literature review. International Journal Knowledge-Based Development 11: 6–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndou, Valentina, Gioconda Mele, and Pasquale Del Vecchio. 2019. Entrepreneurship education in tourism: An investigation among European Universities. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education 25: 100175. [Google Scholar]

- Ndou, Valentina, Giustina Secundo, John Dumay, and Elvin Gjevori. 2018a. Understanding intellectual capital disclosure in online media Big Data: An exploratory case study in a university. Meditari Accountancy Research 26: 499–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndou, Valentina, Giustina Secundo, Giovanni Schiuma, and Giuseppina Passiante. 2018b. Insights for shaping entrepreneurship education: Evidence from the European entrepreneurship centers. Sustainability 10: 4323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schiuma, Giovanni, and Antonio Lerro. Do Cultural and Creative Industries (CCI) matter for innovation and value creation in knowledge-based business? Aims, forms and practice of collaboration in Italy. Paper Presented at the 7th Knowledge Cities World Summit, (KCWS 2014), Tallinn University and World Capital Institute, Tallinn, Estonia, September 24.

- Secundo, Giustina, Valentina Ndou, Pasquale Del Vecchio, and Gianluigi De Pascale. 2019. Knowledge management in entrepreneurial universities: A structured literature review and avenue for future research agenda. Management Decision 57: 3226–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shattock, Michael. 2005. European Universities for Entrepreneurship: Their Role in the Europe of Knowledge the Theoretical Context. Higher Education Management and Policy 17: 13–25. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/edu/imhe/42348745.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- Shattock, Michael. 2006. Managing Successful Universities. Society for Research into Higher Education 52: 753–56. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, Pinaz, Hugues Séraphin, and Nimit R. Chowdhary. 2020. Impact of Covid 19 on tourism situation: Analysis and perspectives. Journal of Teaching in Travel & Tourism 15: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Yigitcanlar, Tan. 2019. Geopolitics of the Knowledge-Based Economy: Sami Moisio. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).