Developing a Maturity Model for the Compliance Function of Investment Firms: A Preliminary Case Study from Norway

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (RQ1)

- How can the effectiveness of the compliance function within investment firms be evaluated using a maturity model?

- (RQ2)

- What is the state of the compliance function within the selected case firm as of today, and how can the function possibly be improved to become more effective?

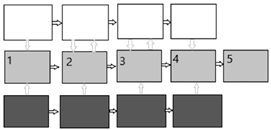

2. Maturity Models

2.1. Definition

2.2. The Modeling Process

3. Developing a Compliance Function Maturity Model

3.1. Phase 1: Planning

A Plan for the CFMM

3.2. Phase: Design

3.2.1. Process Areas

3.2.2. Process Areas of the CFMM

- 1.

- Processes

- 2.

- Resources

- 3.

- Technology

- 4.

- Coordination

- 5.

- Business integrity

3.2.3. Maturity Levels and Their Intersection with the Process Areas

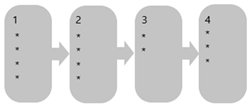

3.2.4. Maturity Stages in the CFMM

- Level 1: Reactive and inconsistent.

- Level 2: Organized but reactive.

- Level 3: Actively managed and understood.

- Level 4: Proactive and implemented.

3.3. Presenting the Compliance Function Maturity Model

4. Testing the CFMM in Practice—An Empirical Illustration

4.1. The Case Firm

4.2. Organization of the Compliance Function

4.3. Maturity Assessment of the Compliance Function

4.3.1. Business Integrity

Fundamental to an effective compliance function is to work preventively and work to create understanding among both management and employees of why the regulations are formed as they are. By this, I simply mean that one must constantly focus on building culture.

The fact that the ethical principles form the basis for every decision in the company means that the management anchors its advice or new processes in these principles, and this, in turn, leads to all employees in the company being ‘forced’ to think about them.

For example, we have a remuneration scheme that hits managers and employees in the front office quite hard. If controls show that they are not compliant with rules and regulations and, for example, give poor advice to a client this is at the expense of the ‘thickness of their wallet’.

The fact that errors and shortcomings are captured by the employees’ closest managers, or through quality controls, means that employees receive concrete feedback on which tasks are to be solved and what the individual must improve.

We are secured through soft values and harsh punishments, in the sense that if you are not compliant, you lose your bonus. This is part of laying the foundation for good compliance assessments to be made.

4.3.2. Resources

The company was actually supposed to put in place an extra resource in the compliance function already in April this year, but the person concerned went on parental leave. As resources were needed it was then arranged so that another person, who was not really to be admitted until August, got to start earlier.

4.3.3. Policies and Processes

4.3.4. Coordination

The fact that the Company has been in great growth has meant that compliance has made discoveries and identified risks which should be left to the first line of defense to rectify. However, the first line has been so congested at times that these things have been downgraded, and compliance has had to be much more involved in the change itself to get these improvements through. That is not really compliance’s task and therefore incorrect use of resources.

4.3.5. Technology

Once the project is in place, the compliance function will have access to better reports. For example, related to order receipt, more automated processes, with systems for flagging or notifications will require fewer resources from compliance being used in, for example, controls related to clients’ mandates.

5. Discussion

5.1. Evaluation of the CFMM

5.1.1. Success Criterion 1: Usability

One must make an overall assessment related to staffing within the compliance function where one assesses what kind of risks the company is exposed to…. and which areas are in focus at the FSA. Based on the overall assessment, the firm must look into what is sufficient in terms of staffing.

Personally, I believe that being conscientious and wanting to do things right, but, at the same time being able to see the business part of it all, is one of the key requirements for an effective compliance function.

Things then are often seen from a very narrow point of view and the legislation is not adapted to fit the business. Compliance then is suddenly considered more of a brake pad and goodwill from the organization is consequently lost.

What if the assessor finds it that the compliance function scores at the highest level for all the key enablers named in the CFMM—but there is lack of knowledge among its employees—can the function really be mature, then?

5.1.2. Success Criterion 2: Usefulness

I believe that the model can make the top management aware of what it actually takes for the compliance function to work effectively. By using the model in an assessment, one is forced to think about each aspect of this.

Maybe that is the way it’s supposed to be, but I feel like the model would be even more useful if it came with an appendix—or like—that provided greater details on how to get from one level to another.

If compliance is seen as a necessary evil, how should one specifically initiate the work of defining business ethics and values?

5.1.3. Sub-Conclusion

5.2. The Process of Developing Maturity Models

5.2.1. Meeting Criticism

5.2.2. Revision Based on Feedback

5.2.3. Sub-Conclusion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Methodological Implications

6.4. Limitations and Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Subject | Suggested Questions |

| Introduction |

|

| General information on internal control and compliance |

|

| More about the compliance function |

|

| «Business integrity» |

|

| «Resources» |

|

| «Policy and processes» |

|

| «Coordination» |

|

| «Technology» |

|

| Usability |

|

| Usefulness |

|

| Conclusion |

|

Appendix B

- -

- How do you think the structure of the model works in terms of usability?

- -

- Is the language in the model understandable?

- -

- Would you consider using this type of model in future work on improving the effectiveness of the compliance function?

- -

- Do you consider the “cell descriptions” to be relevant “guidelines”?

- -

- Did the model in any way trigger reflection or learning?

| Key enablers of an effective compliance function | Technology | All processes are manual. No systems in place. | Some processes are automated while others are manual | All processes are supported by automated systems | All processes are supported by and integrated in one and the same automated system |

| Coordination | No functional access and communication with other business lines | Defined lines of communication with other business lines and mutual functional access. | All business lines work towards shared goals and initiatives | Alignment of strategy, processes, technology to shared goals to improve effectiveness | |

| Policies and processes | Not documented. Ad-hoc in response to incidents. | Defined and documented but not integrated into the workflow | Understood by employees and integrated into the workflow | Integrated into the workflow, continuously measured and improved | |

| Resources | Insufficient resources allocated | Appropriate resources necessary to achieve compliance | Scalable risk-adjusted resource deployment. Assessment done periodically. | Continuously monitored and effectively adapted to changes in compliance requirements | |

| Business integrity | Compliancy viewed as a necessary evil | Business ethics and values are defined centrally | Time is spent consulting and involving employees in business ethics and values | A healthy compliance culture is fostered. Employees naturally promote it. | |

| Reactive and inconsistent | Organized but reactive | Actively managed and understood | Proactive and integrated | ||

| Level of maturity | |||||

References

- ACFE. n.d. Tone at the Top: How Management Can Prevent Fraud in the Workplace. Albany: Association of Certified Fraud Examiners, Dannible and McKee, LLP.

- BAHR. 2017. MiFID II og Norske Aktører. Available online: https://issuu.com/bahr1/docs/mifid_ii_og_norske_akt_rer (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Batenburg, Ronald, Matthijs Neppelenbroek, and Abbas Shahim. 2014. A maturity model for governance, risk management and compliance in hospitals. Journal of Hospital Administration 3: 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baumeister, Roy F., and Mark R. Leary. 1997. Writing narrative literature reviews. Review of General Psychology 1: 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, Joerg, Bjoern Niehaves, Jens Poeppelbuss, and Alexander Simons. 2010. Maturity Models in IS Research. Paper presented at 18th European Conference on Information Systems, ECIS 2010, Pretoria, South Africa, June 7–9; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/221408759_Maturity_Models_in_IS_Research (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Becker, Jörg, Ralf Knackstedt, and Jens Pöppelbuß. 2009. Developing maturity models for IT management. Business & Information Systems Engineering 1: 213–22. [Google Scholar]

- Benbasat, Izak, Albert S. Dexter, Donald H. Drury, and Robert C. Goldstein. 1984. A critque of the stage hypothesis: Theory and empirical evidence. Communications of the ACM 27: 476–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, Dan. 2020. Security Maturity Assessments Focus on People, Process, and Technology. Security Architects Partners. Available online: https://security-architect.com/how-to-assess-security-maturity-and-roadmap-improvements/ (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Brookes, Naomi, Michael Butler, Prasanta Dey, and Robin Clark. 2014. The use of maturity models in improving project management performance: An empirical investigation. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business 7: 231–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, Alan, Emma Bell, and Bill Harley. 2019. Business Research Methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Compliance Week, and Thomson Reuters. 2009. The Compliance Maturity Survey. Available online: https://www.iia.nl/SiteFiles/CW_COMPLIANCE_MATURITY_SURVEY_RESULTS.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2021).

- Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO). 2013. Internal Control–Integrated Framework: Executive Summary; Durham: COSO. Available online: https://www.coso.org/documents/990025p-executive-summary-final-may20.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- De Bruin, Tonia, Michael Rosemann, Ronald Freeze, and Uday Kaulkarni. 2005. Understanding the main phases of developing a maturity assessment model. Paper presented at Australasian Conference on Information Systems (ACIS), Sydney, Australia, November 29–December 2; Australasian Chapter of the Association for Information Systems. pp. 8–19. Available online: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/25152/9/Understanding_the_Main_Phases_of_Developing_a_Maturity_Assessment_Model.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Deloitte. 2017. Compliance Modernization Is No Longer Optional—How Evolved Is Your Approach. New York: Deloitte, Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/us/Documents/regulatory/us-compliance-modernization.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Deloitte. 2018. Compliance Risk Management Powers Performance; Amsterdam: Deloitte. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/nl/Documents/risk/deloitte-nl-risk-compliance-risk-management-powers-performance.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Demiris, George, Debra Oliver, and Karla Washington. 2019. Defining and analyzing the problem. In Behavioral Intervention Research in Hospice and Palliative Care. Edited by George Demiris, Debra Oliver and Karla Washington. Cambridge: Academic Press, pp. 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Domingues, Pedro, Paulo Sampaio, and Pedro M. Arezes. 2016. Integrated management systems assessment: A maturity model proposal. Journal of Cleaner Production 124: 164–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drnevich, Paul L., and Aldas P. Kriauciunas. 2011. Clarifying the conditions and limits of the contributions of ordinary and dynamic capabilities to relative firm performance. Strategic Management Journal 32: 254–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K. 1989. Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review 14: 532–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Kharbili, Marwane, Sebastian Stein, Ivan Markovic, and Elke Pulvermüller. 2008. Towards a framework for semantic business process compliance management. Proceedings of GRCIS 2018: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- ESMA. 2020a. ESMA Provides Guidance on the Compliance Function under MiFID II. Paris: ESMA, Available online: https://www.esma.europa.eu/press-news/esma-news/esma-provides-guidance-compliance-function-under-mifid-ii (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- ESMA. 2020b. Final Report Guidelines on Certain Aspects of the MiFID II Compliance Function Requirements; Paris: ESMA. Available online: https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/library/guidelines_on_certain_aspects_of_mifid_ii_compliance_function_requirements.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Falcione, Andrea, and James McKillop. 2016. PwC State of Compliance Study 2016-Laying a Strategic Foundation for Strong Compliance Risk Management; Los Angeles: PwC. Available online: https://www.pwc.se/sv/pdf-reports/state-of-compliance-study-2016.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2021).

- Falck-Ytter, Kaja. 2021. Visma-sjef:—Dette er hva digitalisering egentlig handler om. In Visma Blogg-Om Teknologi, Regnskap, Skatt, Lønn, Innkjøp, HR. Oslo: Visma, Available online: https://www.visma.no/blogg/vidar-evensen-digitalisering-intervju/ (accessed on 21 February 2021).

- Feise, Jordan. 2020. Compliance Program Maturity Model: How Do You Rank? New York: GAN Integrity, Available online: https://www.ganintegrity.com/blog/compliance-program-maturity-model/ (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Ferrari, Rossella. 2015. Writing narrative style literature reviews. Medical Writing 24: 230–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, Peter, James Moultrie, and Mike Gregory. 2002. The use of maturity models/grids as a tool in assessing product development capability. Paper presented at the IEEE International Engineering Management Conference, Cambridge, UK, August 18–20; pp. 244–49. [Google Scholar]

- Frigo, Mark L., and Richard J. Anderson. 2009. A strategic framework for governance, risk, and compliance. Strategic Finance 90: 20. [Google Scholar]

- Grimstad. 2020. Governance. Advokatfirmaet Erling Grimstad AS. Available online: https://www.governance.no (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Hammer, Michael. 2007. The Process Audit. Harvard Business Review 85: 111–23. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, Jackie. 2004. Compliance and reporting issues arising for financial institutions from money laundering regulations: A preliminary cost benefit study. Journal of Money Laundering Control 7: 333–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hevner, Alan R., Salvatore T. March, Jinsoo Park, and Sudha Ram. 2004. Design Science in Information Systems Research. MIS Quarterly 28: 75–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kazanjian, Robert K., and Robert Drazin. 1989. An empirical test of a stage of growth progression model. Management Science 35: 1489–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenton, Will. 2019. Governance, Risk Management, and Compliance (GRC). Available online: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/g/grc.asp (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Kenton, Will. 2020. How Cost-Benefit Analysis Process Is Performed. Available online: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/cost-benefitanalysis.asp (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Koehn, Daryl. 2005. Integrity as a business asset. Journal of Business Ethics 58: 125–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasrado, Lester Allan, Ravi Vatrapu, and Kim Normann Andersen. 2015. Maturity models development in is research: A literature review. In IRIS Selected Papers of the Information Systems Research Seminar in Scandinavia. Issue Nr 6 (2015). New York: IRIS, Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1005&context=iris2015 (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- Laufer, William S. 1999. Corporate liability, risk shifting, and the paradox of compliance. Vanderbilt Law Review 52: 1341. [Google Scholar]

- Loh, Grace. 2019. GRC Silos and Principled Performance. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/grc-silos-principled-performance-grace-loh-2d (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Maier, Anja M., James Moultrie, and P. John Clarkson. 2011. Assessing organizational capabilities: Reviewing and guiding the development of maturity grids. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management 59: 138–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, Anja M., Matthias Kreimeyer, Clemens Hepperle, Claudia M. Eckert, Udo Lindemann, and P. John Clarkson. 2008. Exploration of correlations between factors influencing communication in complex product development. Concurrent Engineering 16: 37–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maier, Anja, James Moultrie, and P. John Clarkson. 2009. Developing maturity grids for assessing organisational capabilities: Practitioner guidance. Paper presented at the 4th International Conference on Management Consulting: Academy of Management, Vienna, Austria, July 29–August 4. [Google Scholar]

- March, Salvatore T., and Gerald F. Smith. 1995. Design and natural science research on information technology. Decision Support Systems 15: 251–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchant, Kenneth A., and Wim A. Van der Stede. 2017. Management Control Systems: Performance Measurement, Evaluation and Incentives. London: Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Mettler, Tobias. 2011. Maturity assessment models: A design science research approach. International Journal of Society Systems Science 3: 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mitchell, Scott L. 2007. GRC360: A framework to help organisations drive principled performance. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance 4: 279–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oded, Sharon. 2013. Corporate Compliance. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Paulk, Mark C. 2009. A history of the capability maturity model for software. ASQ Software Quality Professional 12: 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Paulk, Mark, Bill Curtis, Mary Beth Chrissis, and Charles Weber. 1993. Capability Maturity ModelSM for Software, Version 1.1. In Software Engineering Institute Technical Report. Pittsburgh: Carnegie Mellon University, Available online: https://resources.sei.cmu.edu/asset_files/TechnicalReport/1993_005_001_16211.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2021).

- Pöppelbuß, Jens, and Maximilian Röglinger. 2011. What Makes a Useful Maturity Model? A Framework of General Design Principles for Maturity Models and Its Demonstration in Business Process Management. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2011/28/ (accessed on 15 August 2021).

- Prorokowski, Lukasz. 2015. MiFID II compliance—Are we ready? Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance 23: 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullen, William. 2007. A public sector HPT maturity model. Performance Improvement 46: 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PwC. 2004. Integrity-Driven Performance-A New Strategy for Success Through IntegratedGovernance, Risk and Compliance Management-A White Paper. Available online: http://www.davidbeam.com/global-compliance-legacy/pdf/PwCIntegrityDrivenPerformance.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Ramakrishna, Saloni. 2015. Enterprise Compliance Risk Management: An Essential Toolkit for Banks and Financial Services. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Röglinger, Maximilian, Jens Pöppelbuß, and Jörg Becker. 2012. Maturity models in business process management. Business Process Management Journal 18: 328–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosemann, Michael, and Tonia De Bruin. 2005. Application of a holistic model for determining BPM maturity. BP Trends 2: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, Dalvinder. 2005. Basel committee on banking supervision: Compliance and the compliance function in banks. Journal of Banking Regulation 6: 298–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Solli-Sæther, Hans, and Petter Gottschalk. 2009. Generations of struggle in stages of growth modeling. Paper presented at the Decision Sciences Institute 40th Annual Meeting New Orleans, New Orleans, LO, USA, November 14–17; pp. 881–87. [Google Scholar]

- Solli-Sæther, Hans, and Petter Gottschalk. 2010. The modeling process for stage models. Journal of Organizational Computing and Electronic Commerce 20: 279–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Solli-Sæther, Hans, and Petter Gottschalk. 2015. Stages-of-growth in outsourcing, offshoring and backsourcing: Back to the future? Journal of Computer Information Systems 55: 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, Richard M. 2011. Governance, Risk Management, and Compliance: It Can’t Happen to Us--Avoiding Corporate Disaster While Driving Success. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, David J., Gary Pisano, and Amy Shuen. 1997. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal 18: 509–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, Gary. 2011. A Typology for the Case Study in Social Science Following a Review of Definition, Discourse, and Structure. Qualitative Inquiry 17: 511–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschoor, Curtis C. 1998. A study of the link between a corporation’s financial performance and its commitment to ethics. Journal of Business Ethics 17: 1509–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, Pedro, and Miguel Mira da Silva. 2011. A Conceptual Model for Integrated Governance, Risk and Compliance. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 199–213. [Google Scholar]

- Wendler, Roy. 2012. The maturity of maturity model research: A systematic mapping study. Information and software technology 54: 1317–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehouse, Antony. 2003. A brave new world: The impact of domestic and international regulation on money laundering prevention in the UK. Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance 11: 138–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Geoff, Trish Greenhalgh, Gill Westhorp, Jeanette Buckingham, and Ray Pawson. 2013. RAMESES publication standards: Meta-narrative reviews. Journal of Advanced Nursing 69: 987–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yeoh, Peter. 2019. MiFID II key concerns. Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance 27: 110–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research Article | Phases | Frameworks Conceptualized |

|---|---|---|

| Becker et al. (2009) |

|  |

| De Bruin et al. (2005) |

|  |

| Solli-Sæther and Gottschalk (2010) |

|  |

| Maier et al. (2011) |

|  |

| Key enablers of an effective compliance function | Technology | All processes are manual. No systems in place. | Some processes are automated while others are manual | All processes are supported by automated systems | All processes are supported by and integrated in one and the same automated system |

| Coordination | No functional access and communication with other business lines | Defined lines of communication with other business lines and mutual functional access. | All business lines work towards shared goals and initiatives | Alignment of strategy, processes, technology to shared goals to improve effectiveness | |

| Policies and processes | Not documented. Ad-hoc in response to incidents. | Defined and documented but not integrated into the workflow | Understood by employees and integrated into the workflow | Integrated into the workflow, continuously measured and improved | |

| Resources | Insufficient resources allocated | Appropriate resources necessary to achieve compliance | Scalable risk-adjusted resource deployment. Assessment done periodically. | Continuously monitored and effectively adapted to changes in compliance requirements | |

| Business integrity | Compliancy viewed as a necessary evil | Business ethics and values are defined centrally | Time is spent consulting and involving employees in business ethics and values | A healthy compliance culture is fostered. Employees naturally promote it. | |

| Reactive and inconsistent | Organized but reactive | Actively managed and understood | Proactive and integrated | ||

| Level of maturity | |||||

| Business integrity | Compliancy viewed as a necessary evil | Business ethics and values are defined centrally | Time is spent consulting and involving employees in business ethics and values | A healthy compliance culture is fostered. Employees naturally promote it. |

| Reactive and inconsistent | Organized but reactive | Actively managed and understood | Proactive and integrated |

| Resources | Insufficient resources allocated | Appropriate resources necessary to achieve compliance | Scalable risk-adjusted resource deployment. Assessment done periodically. | Continuously monitored and effectively adapted to changes in compliance requirements |

| Reactive and inconsistent | Organized but reactive | Actively managed and understood | Proactive and integrated |

| Policies and processes | Not documented. Ad-hoc in response to incidents. | Defined and documented but not integrated into the workflow | Understood by employees and integrated into the workflow | Integrated into the workflow, continuously measured and improved |

| Reactive and inconsistent | Organized but reactive | Actively managed and understood | Proactive and integrated |

| Coordination | No functional access and communication with other business lines | Defined lines of communication with other business lines and mutual functional access. | All business lines work towards shared goals and initiatives | Alignment of strategy, processes, technology to shared goals to improve effectiveness |

| Reactive and inconsistent | Organized but reactive | Actively managed and understood | Proactive and integrated |

| Technology | All processes are manual. No systems in place. | Some processes are automated while others are manual | All processes are supported by automated systems | All processes are supported by and integrated in one and the same automated system |

| Reactive and inconsistent | Organized but reactive | Actively managed and understood | Proactive and integrated |

| Key enablers of an effective compliance function | Technology | All processes are manual. No systems in place. | Some processes are automated while others are manual | All processes are supported by automated systems | All processes are supported by and integrated in one and the same automated system |

| Coordination | No functional access and communication with other business lines | Defined lines of communication with other business lines | All business lines work towards shared goals and initiatives | Alignment of strategy, processes, technology to shared goals to improve effectiveness | |

| Policies and processes | Not documented. Ad-hoc in response to incidents. | Defined and documented but not integrated into the workflow | Understood by employees and integrated into the workflow | Integrated into the workflow, continuously measured and improved | |

| Resources | Insufficient resources allocated | Appropriate resources necessary to achieve compliance | Scalable risk-adjusted resource deployment. Assessment done periodically. | Continuously monitored and effectively adapted to changes in compliance requirements | |

| Business integrity | Compliancy viewed as a necessary evil | Business ethics and values are defined centrally | Time is spent consulting and involving employees in business ethics and values | A healthy compliance culture is fostered. Employees naturally promote it. | |

| Reactive and inconsistent | Organized but reactive | Actively managed and understood | Proactive and integrated | ||

| Level of maturity | |||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Holter Antonsen, H.; Madsen, D.Ø. Developing a Maturity Model for the Compliance Function of Investment Firms: A Preliminary Case Study from Norway. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11040109

Holter Antonsen H, Madsen DØ. Developing a Maturity Model for the Compliance Function of Investment Firms: A Preliminary Case Study from Norway. Administrative Sciences. 2021; 11(4):109. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11040109

Chicago/Turabian StyleHolter Antonsen, Helena, and Dag Øivind Madsen. 2021. "Developing a Maturity Model for the Compliance Function of Investment Firms: A Preliminary Case Study from Norway" Administrative Sciences 11, no. 4: 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11040109

APA StyleHolter Antonsen, H., & Madsen, D. Ø. (2021). Developing a Maturity Model for the Compliance Function of Investment Firms: A Preliminary Case Study from Norway. Administrative Sciences, 11(4), 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11040109