1. Introduction

Unsustainable production and consumption patterns are the main causes of environmental deterioration, with economic activities deteriorating the environment through resource use and waste production. In this context, the circular economy business model has become increasingly popular to create sustainable businesses, since the concept of a circular economy could help to solve challenges such as resource scarcity and climate change reducing the consumption of natural resources and increasing the recycling of materials and products within the economy (

Tunn et al. 2019).

More precisely, the circular economy supports the transformation of the linear consumption model into a closed-production model, so that production and consumption waste is reused and incorporated into the economy to create more value, while encouraging the economic activities that reduce, reuse and recycle materials in production, distribution and consumption processes. Therefore, the circular economy aims to keep products, components, materials, and energy in circulation to continue increasing and maintaining their value over a long period of time, which involves changes in the traditional business models.

A sustainable business model can change production and consumption patterns, defining how a company develops business and shapes the company–consumer relationship. For this purpose, companies could follow the circularity model, adopting a closed-loop system where resources are returned to the natural environment after use. The concept of circularity is often examined from a business and production model, and researchers are beginning to explore the role of the consumer in closed production models (

Wang et al. 2018), highlighting the low consumer awareness and interest in a circular economy (

Sijtsema et al. 2020) or reporting the circular attributes perceived as favorable by consumer businesses (

Stein et al. 2020).

Further, an appropriate strategy is required to attract environmentally conscious consumers toward circular goods. The reason is that consumers play a critical role in the circular economy strategy (

Gallaud and Laperche 2016), since their choices can support or hamper the circular economy and their decisions determine whether products are consumed through circular consumption processes. However, important aspects related to the role of consumers remain unexplored in product circularity. The focus of a circular economy has widely been on the company side of circularity, instead of focusing on the market side, and accordingly, the literature offers few insights into consumers’ acceptance of recycled circular goods. In this context, the main purpose of this study is providing an empirical investigation on consumers’ acceptance and purchase intention of recycled circular goods, and to examine what are the most important variables driving consumers’ behavior towards these circular products.

Finally, the present research is structured as follows. Firstly, a literature review is provided in

Section 2. Secondly, the research hypotheses development is formulated and the methodology is described in

Section 3 and

Section 4, respectively. Next, the results are presented and discussed in

Section 5 and

Section 6;

Section 7 reports some conclusions, implications and the research limitations.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Sustainable Model of Circular Economy

The basic philosophy of the circular economy is that natural resources are considered to be finite; and consequently, the circular economy is a pathway towards a more sustainable economic development. More precisely, the concept of circular economy originates in the inability of linear production models to reconcile current levels of production and consumption with the limited availability of resources (

Bradley et al. 2018).

Nowadays, the dominant economic model is based on a

linear consumption model of “

consume–use–waste” (

Figure 1) where natural resources and raw materials are extracted, processed into final goods and then become waste after they have been consumed (

Su et al. 2013). Conversely, the circular economy provides an alternative model of consumption which is a

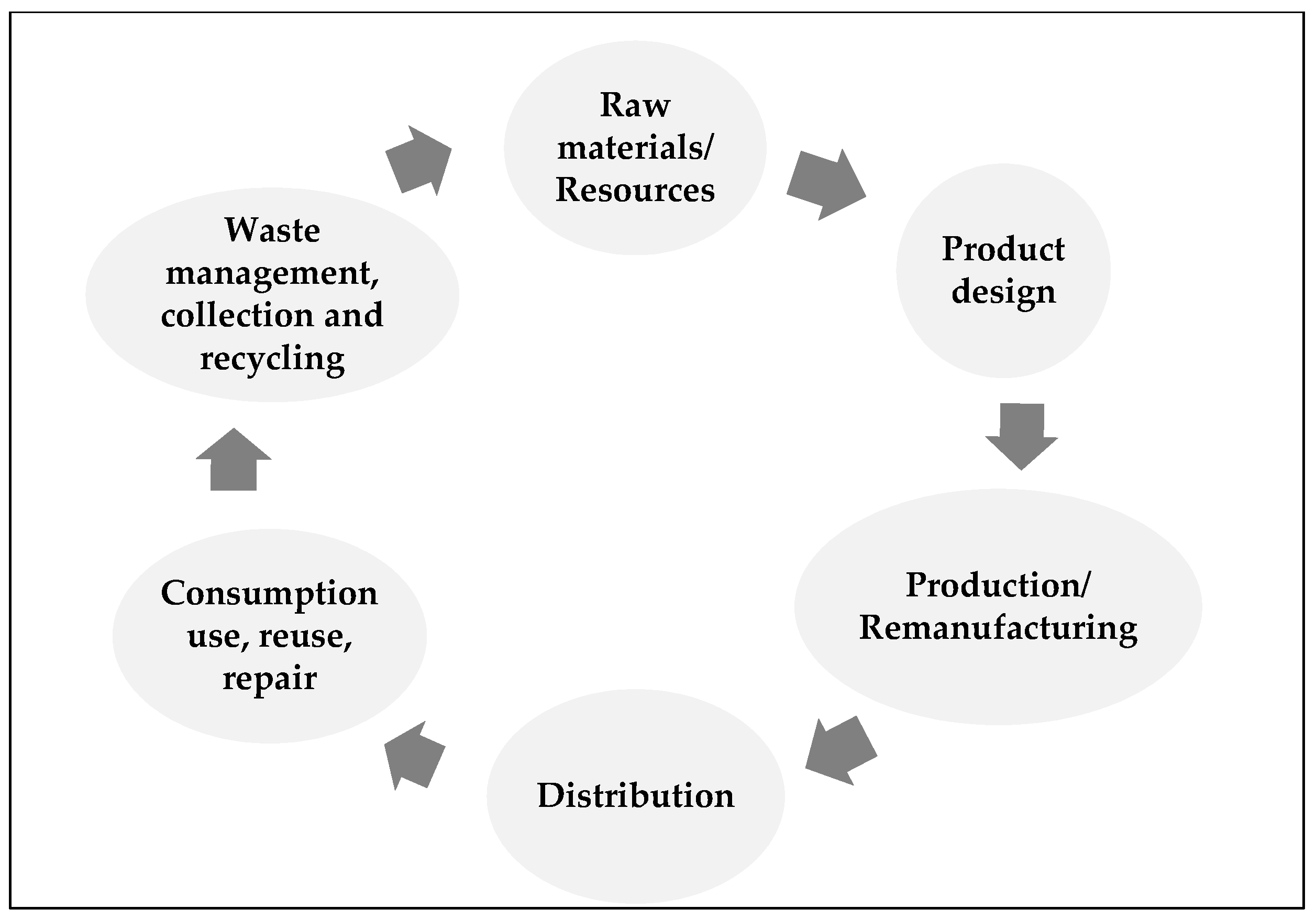

closed production model (

Figure 2) where resources are reused and kept in a loop of production and usage, allowing the generation of more value (

Su et al. 2013;

Urbinati et al. 2017). Therefore, in a circular economy, products and materials continuously circulate in so-called loops as long as they can provide value.

The circular economy strategy aims to transform in depth the traditional economic model replacing the existing linear production model with a closed production model. In fact, the shift from today’s predominantly linear “

consume–use–waste” business model to a circular economy model has a great potential to reduce the associated negative environmental impacts (

Selvefors et al. 2019). For this reason, the circular economy is perceived as a business model that implements sustainability (

Brennan et al. 2015).

Similarly, authors such as

Kirchherr et al. (

2017) indicate that circular economy could be understood as using post-consumption products, materials and resources to create new value through the exchange of linear flows of energy and materials for “

closed-loop” systems of production and consumption. For this purpose, the circular economy aims to keep components and materials in “

closed loops” for as long as possible, and promotes the return of the waste to the economy and the minimization of resource consumption (

Tunn et al. 2019). Consequently, circular products positively contribute to the environment through the reduction of consumption of energy, materials and resources (

Jena and Sarmah 2015).

2.2. The Principles of Circular Economy

The circular economy could be defined as covering the activities of reduce, reuse, and recycle in the process of production, circulation, and consumption. As a consequence, prior studies highlight the “3R” principles of circular economy—reduce, reuse, and recycle—as the main actions leading to circular economy and that focus on recapturing value from waste materials by circulating them across supply chains (

Ghisellini et al. 2016).

The

reduce principle supports the minimization of the overall amount of materials, resources and waste generated in the economic model through the increase of efficiency in production and consumption, while reducing waste and the environmental impact (

Ghisellini et al. 2016). Secondly, the

reuse principle supports that materials, products and components that are not wasted, are used again for the same purpose that they were conceived (

European Parliament and the Council of the European Union 2008). The reason is that reusing materials and products requires fewer resources and less energy than producing new ones (

Castellani et al. 2015). Third, the

recycle principle refers to any recovery operation by which waste materials are reprocessed into products, materials or components whether for the original or for other purposes (

European Parliament and the Council of the European Union 2008). Therefore, recycling entails a process through which used or discarded materials as treated to make them appropriate for reuse. Consequently, the circular economy treats waste and discarded materials as a valuable resource (

Hazen et al. 2017), since this sustainable business model promotes wastage valorization, recovering materials otherwise wasted, yielding multiple environmental, economic and social benefits (

Coderoni and Perito 2020).

2.3. Sustainable Consumption for a Sustainable Business Strategy

Sustainable consumption behavior is a complex phenomenon that was first conceptualized as “the use of goods and services that respond to basic needs and bring a better quality of life, while minimizing the use of natural resources, toxic materials and emissions of waste over the life cycle, so as not to jeopardize the needs of future generations” (

Ofstad 1994). Other authors indicate that sustainable consumption entails satisfying consumer needs, while reducing negative impacts caused in resource extraction, production and consumption (

Cooper 2013). Similarly,

Tunn et al. (

2019) report that sustainable consumption means shaping and satisfying consumer needs to reduce the negative impacts of consumption on the environment and social and economic life.

The business model offers a holistic approach to analyze how companies create and capture value (

Zott et al. 2011); and further the sustainable business models integrate the sustainability impact of the model, considering societal costs and benefits and the circulation of materials (

Dewulf 2010). Similarly, the sustainable business model translates circularity into value and to sustainable business strategies that deal with the products’ design, manufacturing, processing, distribution and products’ marketing. In addition, the sustainable business models have been considered as key drivers of the transition towards a circular economy. Circular economy represents a strategy that entails economic growth without increasing consumption of resources, deeply transforming production chains and consumption habits (

European Commission 2014). Therefore, it can be stated that the circular economy strategy supports the transformation of traditional consumption models to achieve economic sustainability

In this context, the circular economy and sustainable business models are potential enablers of sustainable consumption, through the modification of production processes and consumption patterns (

Bocken 2017), such as for example, the recovery and reuse of materials and components at the end of product life, such as wastage.

However, consumers play a critical role in circular economy (

Gallaud and Laperche 2016) and for this reason, it is crucial to understand their acceptance towards circular products. Most consumers are willing to consume environmentally sustainable products, but the real incorporation of these products into their regular purchases is less evident (

Cronin et al. 2011). What are the reasons for this behavior? Prior research indicates that some consumers tend to perceive environmentally sustainable products as deficient in salient product attributes (

Luchs et al. 2010), or perceive these products as having poor quality, performance or safety (

Wang et al. 2018). Some other authors point out that consumers may have options to shift to circular consumption patterns, but these options are often considered impractical and inconvenient (

Selvefors et al. 2019). In addition, the lack of consumer interest and awareness is one of the major barriers in the transition from linear business models to circular business strategies (

Kirchherr et al. 2018). Therefore, to make circular consumption preferable, it is essential to increase the understanding of what circular consumption entails.

3. Research Hypotheses

3.1. Perceived Quality of Recycled Products

The concept of perceived quality could be defined as the individual’s subjective judgment regarding a product’s superiority or excellence (

Zeithaml 1988). However, what happens with recycled products? Previous research has demonstrated that when a product is recycled, this fact can decrease consumers’ quality expectations of the product (

Lin and Chang 2012;

Wang et al. 2013). Furthermore, even though some consumers could perceive that recycled products contribute to environmental issues, these products may appear to be of lower quality or more contaminated (

Baxter et al. 2017). This feeling of contamination occurs because individuals feel uncomfortable and disgusted when using specific products that contain recycled materials. The reason that could explain the lower quality perception of recycled products is that consumers might feel uncertain about the quality because they are unaware or have a lack of knowledge of the steps followed by the manufacturer to return waste materials to a like-new product condition (

Hazen et al. 2017;

Jena and Sarmah 2015). Therefore, a lack of understanding of recycled products manufacturing process fosters low-quality perceptions and reduces consumers’ purchase intention.

In this context, manufacturers should not have the idea that recycled products developed from recovered materials or from wastage will be preferred over new products. Conversely, manufacturers need to make recycled products attractive enough to compensate for the prejudice about the low quality associated with products made from discarded materials in order to compete with new products in the marketplace (

Singh and Ordoñez 2016).

On the other hand, the purchase intention could be defined as the willingness of an individual to buy a specific product or service, and perceived quality has been found to influence consumer purchase intention (

Dodds et al. 1991). Consequently, if a product is perceived to have low quality, then purchase intention is expected to be low; and consumers may be reluctant to purchase recycled products if they doubt the quality of these products. Therefore, the following research hypothesis is presented:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). The perceived product quality of recycled products has a negative influence on consumers’ purchase intention.

3.2. The Image of Recycled Products

Recycled products can be positioned in consumers’ minds as environmentally friendly and “

green products”; thus, having a positive image among consumers. The reason is that recycling and remanufacturing processes reduce waste, reuse discarded material and require less energy and natural resources than the manufacturing processes of new products (

Michaud and Llerena 2011). Similarly, the image of “

green products” represents the beliefs that individuals hold regarding how effective these products are in reducing threats to the environment (

Chang 2011). The positive image of such products, as well as the growing sensitivity to environmental issues has shifted consumer behavior, including an increased demand and a greater acceptance of recycled products (

Tsen et al. 2006) and a greater willingness to pay more for these products (

Laroche et al. 2001).

One factor influencing the positive image of recycled products is consumers’ favorable attitude towards them. Prior studies highlight that consumers’ attitudes towards recycled products are generally positive (

Anstine 2000); and that they may develop a positive attitude towards recycled products to express social responsibility through their purchase (

Hamzaoui and Linton 2010). Therefore, it can be assumed that consumers who are aware of the possibilities of recycling and turn wastage and used materials into new products, will be more positive about recycled products (

Magnier et al. 2019). Therefore, considering all the above, the following hypothesis is posed:

Hypothesis 2 (H2). The positive/favorable image of recycled products has a positive influence on consumers’ purchase intention.

3.3. Sustainability/Environmental Benefits of Recycled Products

The sustainability awareness and environmental concern of individuals may influence their behavior. More precisely, the environmental concern could be defined as the extent to which consumers are worried about threats to the environment (

Lee et al. 2014), influencing pro-environmental behaviors such as recycling purchasing. Similarly, the sustainable consumption behavior is the result of considering not only consumers’ needs, but also social and environmental responsibility (

Vermeir and Verbeke 2006). Therefore, consumers tend to engage in sustainable behaviors when they believe they can make a difference for solving environmental issues (

Park and Lin 2018).

Similarly, previous research reports that perceived sustainability, product circularity and a recycled appearance have a positive effect on perceived environmental benefits (

Michaud and Llerena 2011), influencing the behavior of consumers with a high level of environmental concern (

Magnier et al. 2019).

What are the major causes driving this environmental concern? The literature highlights the existence of an ethic responsible consumer who expresses responsibility towards environment through purchase decision making. In this context, authors such as

Tan (

2011) report that the environmental knowledge is the factor leading to the development of attitudes and a behavioral pattern of environmental concern. We can, therefore, expect that consumers with a high level of environmental concern may be willing to support recycled products due to their environmental benefits.

On the other hand, previous studies indicate consumers prefer purchasing recycled products because of their concern and awareness of environmental issues (

Wang et al. 2013;

Hazen et al. 2017) and when they are strongly involved with the environment. That is, consumers are prone to purchase recycled products when they are aware of the environmental benefits provided by them (

Wang et al. 2016). Thus, the following research hypothesis is posed:

Hypothesis 3 (H3). The sustainability of recycled products has a positive influence on consumers’ purchase intention.

3.4. Safety of Recycled Products

Following

Grewal et al. (

1994), the product safety is related with the risks that encompass the potential negative consequences associated with purchasing a specific product; and accordingly, the reduction of the perceived safety could play a negative role in the adoption of products. For this reason, attention should be paid to consumers’ perception about the safety of recycled or “

waste-to-value” products, given the relevance of the consumer thoughts about the safety of circular recycled products.

Prior studies on consumers’ evaluations of recycled products shed light on the perceived risks that could hamper the adoption of these products (

Anstine 2000;

Michaud and Llerena 2011). In this vein, the consumer evaluation of a recycled product is closely related to the perceived risk associated with the product (

Hamzaoui and Linton 2010), reflecting the risks associated with the outcome and consequences of the “circular” purchase. More precisely, a higher perceived risk reduces consumers’ willingness to purchase recycled products (

Hamzaoui and Linton 2010).

One factor related with recycled products’ safety is contamination. Products that are intended to be sustainable and environmentally responsible may not be accepted by consumers because of their contamination. More precisely, some consumers perceive products made from used and wastage materials as contaminated, decreasing their purchase intentions (

Meng and Leary 2019).

Another factor related with product perceived safety is uncertainty. In general terms, consumers face some level of uncertainty when making purchase decisions, and such uncertainties may act as inhibiting the purchase decision (

Sweeney et al. 1999). Regarding recycled products, these uncertainties involve the unknown processes used to manufacture the product, the lack of previous experience with recycled products, or the lack of knowledge about product safety (

Hazen et al. 2017). Consequently, the uncertainty regarding recycled products negatively influences their safety perception (

Hazen et al. 2017). Therefore, considering all the explained above, it can be stated that recycled products can have a negative impact on perceived safety, negatively influencing consumers’ purchase intention (

Magnier et al. 2019), and in turn, the following hypothesis is posed:

Hypothesis 4 (H4). The perceived safety of recycled products has a negative influence on consumers’ purchase intention.

4. Methodology

4.1. Variables and Measurement Scale

To the authors’ knowledge there are no previous surveys on the consumers’ acceptance of recycled products; and for this reason, research participants were asked to evaluate these products on different measurement scales and indicators validated in the previous literature. The descriptive measures of means and standard deviations are shown in

Table 1. Firstly, the recycled product

perceived quality was measured on a three-item scale adopted from

Dodds et al. (

1991). Then, the

product image was examined using three items adopted from

Netemeyer et al. (

2004). The recycled product’s

sustainability and environmental benefits were gauged with a two-item scale adapted from

Chang (

2011) and

Mugge et al. (

2017). For measuring the product safety, three items proposed by

Magnier et al. (

2019) were adopted; while consumers’

purchase intention was examined using three items proposed by

Mugge et al. (

2017). Participants indicated their level of agreement with the proposed items on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = “strongly disagree”; 5 = “strongly agree”).

4.2. Sampling and Fieldwork

A structured questionnaire was developed based on an extensive literature review on sustainability. Then, an internet based self-administered questionnaire was used to collect data in March 2019 among consumers residing in Spain on a random basis. More precisely, participants were reached through different social media networks such as Facebook and Whatsapp. Prior to answering the questions, the research topic was introduced to participants, explaining the case of the Spanish company Ecoalf, which uses garbage as a valuable resource and transforms plastic debris into fashion products and accessories. Therefore, in the introduction, we explained to research participants that this company collects plastic from the Mediterranean Sea and converts it into fashion garments through a process of reverse logistics. After this brief introduction, participants were briefly informed about the research purpose.

Next, participants were asked to rate the variables related to their acceptance and purchase intention of recycled products. The last section of the questionnaire gathered socio-demographic and economic information. A total amount of 386 questionnaires were sent out, gathering 312 valid questionnaires, yielding a sampling error of 5.7% at a confidence level of 95%. This sample size exceeds the recommended minimum, given the size of the model (

Hair et al. 2017).

Regarding the sample profile, 52.3% of the participants were female, while 47.7% were men. A percentage of 28.1% of the participants were between the ages of 31 to 40, while 21.1% were between 41 and 50; and 18.2% were between 20 and 30 years old. In terms of education level, 26% of participants had primary education, while 33.6% had secondary education and more than 34.2% of the participants had university studies. Regarding the household income, the majority of participants (32.8%) had an income of 30.000–42.000 €.

5. Results

5.1. Results of the Measurement Model

Partial Least Squares (PLS) path modelling was applied for the analysis and estimation using the Smart PLS 3.0. software (

Ringle et al. 2015) to examine the proposed model and to test the research hypotheses (

Table 2). Before testing the paths and their coefficients, the measurement model was tested for reliability, validity and internal consistency. First, the internal consistency and reliability were examined through Cronbach’ alpha and composite reliability (CR). The results show that constructs achieve composite reliability higher than 0.70 and the values of Cronbach’s alpha for the constructs was greater than 0.70 (

Hair et al. 2017), indicating an adequate internal consistency. In addition, standardized loadings indicate the need to remove item Qual3 from the initial measurement scale. Then, convergent validity was examined through the analysis of the factor loadings that achieve values higher than the commonly accepted threshold of 0.70 (

Fornell and Larcker 1981) and through the values of the average variance extracted (AVE) that are higher than 0.50 (

Fornell and Larcker 1981); thus, indicating adequate values.

Finally, the discriminant validity of the scale was examined by assessing all possible paired combinations of constructs (

Table 3). Since the square root values of AVE for all constructs were higher than the inter-construct correlations, the discriminant validity of all constructs was established (

Fornell and Larcker 1981).

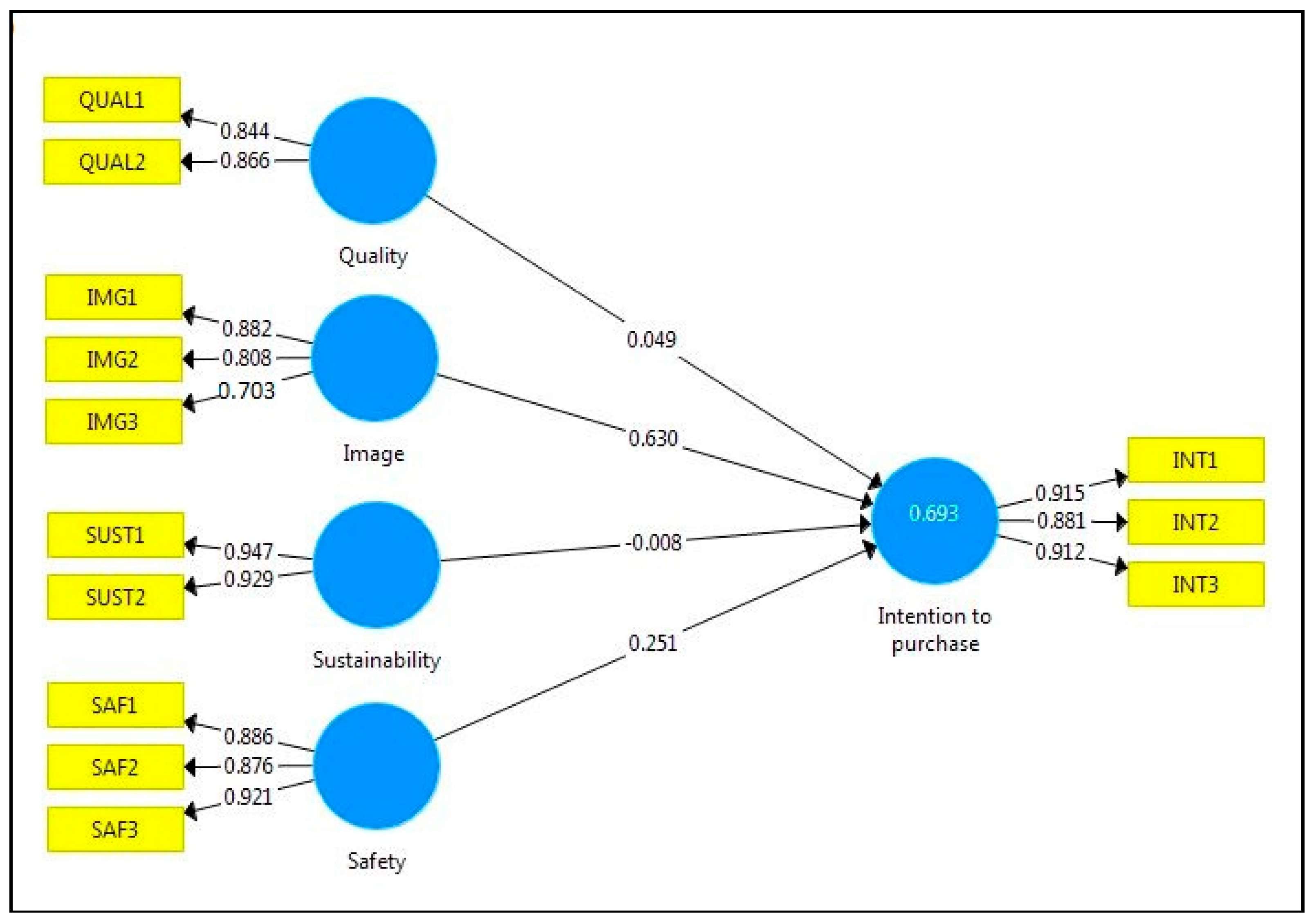

5.2. Results of the Structural Model

The structural model and the relationship between the constructs are analyzed through the coefficients of determination R

2 (explained variance) and

f2 (effect size) according to

Hair et al. (

2017), as shown in

Table 4. The coefficient of determination (R

2 value) represents a measure of in-sample predictive power (

Hair et al. 2017) and the obtained findings indicate an R

2 value of 0.693, meaning that 69% of recycled products’ purchase intention is explained by the independent variables. In addition, the

f2 effect size measures the strength of each variable in explaining endogenous variables (

Hair et al. 2017); and our results show that the

f2 effect size of the constructs are above the 0.02 accepted threshold. Finally, the collinearity analysis tests for variance inflation factor (VIF) values are below 5 (

Hair et al. 2017), thus indicating an adequate structural model.

6. Discussion

Table 5 shows the path coefficients of the relationship between variables and consumers’ purchase intention, corresponding

t-values and the level of significance. The obtained results indicate that consumers’ intention to purchase recycled products is significantly influenced by their positive and favorable image and by their perceive safety. More precisely, when examining consumers’ acceptance of recycled products, the product image was found to have the highest impact on purchase intention (β

4 = 0.630 **;

p = 0.000). Similarly, a direct significant impact was found for product safety on purchase intention (β

1 = 0.251 **;

p = 0.003), with its influence on purchase intention being slightly lower than image. Therefore, the positive image and the product safety is the stepwise order of the influence of the attributes of recycled products on purchase intention. Therefore, it can be stated that the better product image—understood as positive favorable image—and the greater product perceived safety, the greater the consumer purchase intention.

On the other hand, the perceived quality of recycled products does not show a significant influence on consumers’ purchase intention (β

4 = 0.049

ns;

p = 0.649). One potential explanation is that, as reported in the previous literature, the strong quality concerns regarding recycled products influence consumers’ acceptance and purchase intention of such products (

Hazen et al. 2017). Similarly, product sustainability or environmental benefits of recycled products showed no statistical significance on purchase intention (β

4 = −0.008

ns;

p = 0.917), since this relationship failed to reach statistical significance. This result could suggest that as long as customers have a positive image of recycled products in their minds and perceive an adequate product safety, the product environmental benefits are not relevant for consumers regarding their purchase decision.

Finally, our findings provide support for two of the proposed research hypotheses, since hypotheses H2 and H4 were supported.

Figure 3 shows the results obtained for the path analysis.

7. Conclusions

Some companies participate in the circular economy through the production of recycled products; however, these initiatives will only be successful if consumers are willing to adopt these circular products. Therefore, consumers’ acceptance of recycled products is a key factor for ensuring the success of circular business models. In this context, this research aims to gain understanding of the determinants of consumers’ acceptance for recycled products. The obtained findings indicate that product image, followed by safety, are the main drivers of consumers’ purchase intention of recycled circular products. Therefore, research has identified the positive image and safety of the product as the important issues when deciding whether or not to purchase recycled products. Contrary to the initial expectations, the present research does not support the influence of perceived quality and product environmental benefits on consumers’ acceptance of recycled products. Therefore, this research contributes to the theory-building in sustainable business models providing an empirical foundation for the importance of the role of consumers in circular economy models and their acceptance of recycled circular goods.

This research provides useful insights for managers into consumers’ acceptance of recycled products. The reason is that only when companies fully understand the acceptance of consumers toward circular goods, can better strategies developed for in order to meet the market demand. In general terms, companies following sustainable business strategies should engage consumers through awareness-raising communication campaigns and education on the consumption of circular goods, providing consumers with adequate information about recycled products and their characteristics. Similarly, companies should promote product safety, such as presenting objective proofs of the innocuousness of recycled products, and develop strategies to eliminate the risk of perceived contamination. In addition, and considering the lack of influence of the perceived product quality of these products, managers should also develop educational and awareness campaigns in order to help consumers mitigate the poor perception about the quality of recycled products.

This research, nonetheless, has limitations representing avenues for future research. In the first place, the research sample size is sufficient for an exploratory study to gain insights into this field of knowledge, but future research could develop larger samples in order to allow further generalizations. Secondly, future research could include other relevant product-related and consumer-related variables that were not included in this study, such as for example, consumer involvement with circularity, consumer attitude, price of circular products, products’ functionality or even the convenience of circular goods. Third, this study did not investigate the effect of brands on responses to recycled products; and in turn, future research could research the influence of product brands on consumers’ acceptance of circular goods. Finally, some limitations could derive the social media networks used in order to gather consumers’ information.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, C.C.-P. and J.-P.L.-M.; formal analysis and investigation, C.C.-P. and J.-P.L.-M.; resources, C.C.-P.; writing and draft preparation, C.C.-P. and J.-P.L.-M.; review and editing, J.-P.L.-M.; visualization and supervision, C.C.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Anstine, Jeff. 2000. Consumers’ willingness to pay for recycled content in plastic kitchen garbage bags: A hedonic price approach. Applied Economic Letters 7: 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, Wenston, Marco Aurisicchio, and Peter Childs. 2017. Contaminated interaction: Another barrier to circular material flows. Journal of Industrial Ecology 21: 507–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, Nancy. 2017. Business-led sustainable consumption initiatives: Impacts and lessons learned. Journal of Management Development 36: 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, Ryan, I. S. Jawahir, Fazleena Badurdeen, and Keith Rouch. 2018. A total life cycle cost model (TLCCM) for the circular economy and its application to post-recovery resource allocation. Resources, Conservation & Recycling 135: 141–49. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, Geraldine, Mike Tennant, and Fenna Blomsma. 2015. Business and Production Solutions: Closing Loops and the Circular Economy. Edited by Helen Kopnina and John Blewitt. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Castellani, Valentina, Serenella Sala, and Nadia Mirabella. 2015. Beyond the throwaway society: A life cycle-based assessment of the environmental benefit of reuse. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management 11: 373–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Ching. 2011. Feeling ambivalent about going green. Journal of Advertising 40: 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coderoni, Silvia, and Maria A. Perito. 2020. Sustainable consumption in the circular economy. An analysis of consumers’ purchase intentions for waste-to-value food. Journal or Cleaner Production 252: 119879. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, Tim. 2013. Sustainability, consumption and the throwaway culture. In The Handbook of Design for Sustainability. Edited by Stuart Walker, Jacques Giard and Walker Helen. London and New York: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin, Joseph R., Jeffery S. Smith, Mark R. Gleim, Edward Ramirez, and Jennifer D. Martinez. 2011. Green marketing strategies: An examination of stakeholders and the opportunities that they present. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 39: 158–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewulf, Kristel. 2010. Play it forward: A Game-based tool for Sustainable Product and Business Model Innovation in the Fuzzy Front End. In Knowledge Collaboration & Learning for Sustainable Innovation. Delft: University of Technology. [Google Scholar]

- Dodds, William B., Kent B. Monroe, and Drew Grewal. 1991. Effect of price, brand name, and store name on buyer’s perception of product quality. Journal of Marketing Research 28: 307–19. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 2014. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: Towards a Circular Economy: A Zero Waste Program for Europe. Brussels: European Commission. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. 2008. Directive 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on Waste and Repealing Certain Directives. Brussels: Official Journal of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, Claes, and David F. Larcker. 1981. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research 18: 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallaud, Delphine, and Blandine Laperche. 2016. Circular Economy, Industrial Ecology and Short Supply Chain. London: Wiley Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Ghisellini, Patrizia, Catia Cialani, and Sergio Ulgiati. 2016. A review on circular economy: The expected transition to a balanced interplay on environmental and economic systems. Journal of Cleaner Production 114: 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, Drew, Jerry Gotlieb, and Howard Marmorstein. 1994. The moderating effects of message framing and source credibility on the price-perceived risk relationship. Journal of Consumer Research 21: 145–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., Tomas G. Hult, Christian M. Ringle, and Marko Sarstedt. 2017. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Hamzaoui, Leila E., and Jonathan D. Linton. 2010. New or recycled products: How much are consumers willing to pay? Journal of Consumer Marketing 27: 458–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazen, Benjamin T., Diane A. Mollenkopf, and Yacan Wang. 2017. Remanufacturing for the circular economy: An examination of consumer switching behavior. Business Strategy and the Environment 26: 451–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, Sarat K., and Sarada P. Sarmah. 2015. Measurement of consumers’ return intention index towards returning the used products. Journal of Cleaner Production 108: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, Julian, Denise Reike, and Marko Hekkert. 2017. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resources, Conservation & Recycling 127: 221–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchherr, Julian, Laura Piscicelli, Ruben Bour, Erica Kostense-Smit, Jennifer Muller, Anne Huibrechtse-Truijens, and Marko Hekkert. 2018. Barriers to the circular economy: Evidence from the European Union (EU). Ecological Economics 150: 264–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, Michel, Jasmin Bergeron, and Guido Barbaro-Forleo. 2001. Targeting consumers who are willing to pay more for environmentally friendly products. Journal of Consumer Marketing 18: 503–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Yong-Ki, Sally Kim, Min-Seong Kim, and Jeang-Gu Choi. 2014. Antecedents and interrelationships of three types of pro-environmental behavior. Journal of Business Research 67: 2097–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Ying-Ching, and Angela C. A. Chang. 2012. Double standard: The role of environmental consciousness in green product usage. Journal of Marketing 76: 125–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchs, Michael G., Rebecca W. Naylor, Julie R. Irwin, and Rajagopal Raghunathan. 2010. The sustainability liability: Potential negative effects of ethicality on product preference. Journal of Marketing 74: 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnier, Lise, Ruth Mugge, and Jan Schoormans. 2019. Turning ocean garbage into products-consumers’ evaluations of products made of recycled ocean plastic. Journal of Cleaner Production 215: 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Matthew D., and Bret R. Leary. 2019. It might be ethical, but I won’t buy it: Perceived contamination of, and disgust towards, clothing made from recycled plastic bottles. Psychology & Marketing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaud, Celine, and Daniel Llerena. 2011. Green consumer behaviour: An experimental analysis of willingness to pay for remanufactured products. Business Strategy and the Environment 20: 408–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugge, Ruth, Boris Jockin, and Nancy Bocken. 2017. How to sell refurbished smartphones? An investigation of different customer groups and appropriate incentives. Journal of Cleaner Production 147: 284–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netemeyer, Richard G., Balaji Krishnan, Chris Pullig, Guangping Wang, Mehmet Yaggi, Dwane Dean, Joe Ricks, and Ferdinand Wirth. 2004. Developing and validating measures of facets of customer-based brand equity. Journal of Business Research 57: 209–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofstad, Sylvi. 1994. Symposium: Sustainable Consumption. Oslo: Ministry of Environment. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Hyun-Jung, and Li M. Lin. 2018. Exploring attitude–behavior gap in sustainable consumption: Comparison of recycled and upcycled fashion products. Journal of Business Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, Christian, M. Sven Wende, and Jan-Michael Becker. 2015. SmartPLS3. Boenningstedt: SmartPLS GmbH. Available online: http://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 14 May 2019).

- Selvefors, Anneli, Oskar Rexfelt, Sara Renström, and Helena Strömberg. 2019. Use to use: A user perspective on product circularity. Journal of Cleaner Production 223: 1014–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijtsema, Siet J., Harriete M. Snoek, Mariet A. van Haaster-de Winter, and Hans Dagevo. 2020. Let’s Talk about Circular Economy: A Qualitative Exploration of Consumer Perceptions. Sustainability 12: 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Jagdeep, and Isabel Ordoñez. 2016. Resource recovery from post-consumer waste: Important lessons for the upcoming circular economy. Journal of Cleaner Production 134: 342–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, Nicole, Stefan Spinler, Helga Vanthournout, and Vered Blass. 2020. Consumer Perception of Online Attributes in Circular Economy Activities. Sustainability 12: 1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Biwei, Almas Heshmati, Yong Geng, and Xiaoman Yu. 2013. A review of the circular economy in China: Moving from rhetoric to implementation. Journal of Cleaner Production 42: 215–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, Jillian C., Geoffrey N. Soutar, and Lester W. Johnson. 1999. The role of perceived risk in the quality-value relationship: A study in a retail environment. Journal of Retailing 75: 77–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Booi-Chen. 2011. The roles of knowledge, threat, and PCE on green purchase behaviour. International Journal of Business and Management 6: 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsen, Chyong, Grace Phang, Haslinda Hasan, and Merlyin R. Buncha. 2006. Going green: A study of consumers’ willingness to pay for green products in Kota Kinabalu. International Journal of Business and Society 7: 40–54. [Google Scholar]

- Tunn, Vivian S., Nancy M. Bocken, Ellis A. van den Hende, and Jan P. Schoormans. 2019. Business models for sustainable consumption in the circular economy: An expert study. Journal of Cleaner Production 212: 324–33. [Google Scholar]

- Urbinati, Andrea, Davide Chiaroni, and Vittorio Chiesa. 2017. Towards a new taxonomy of circular economy business models. Journal of Cleaner Production 168: 487–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, Iris, and Wim Verbeke. 2006. Sustainable food consumption: Exploring the consumer attitude e behavioral intention gap. Journal of Agricultural & Environmental Ethics 19: 169–94. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Yacan, Vincent Wiegerinck, Harold Krikke, and Hongdan Zhang. 2013. Understanding the purchase intention towards remanufactured product in closed-loop supply chains. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 43: 866–88. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Yacan, Joseph R. Huscroft, Benjamin T. Hazen, and Mingyu Zhang. 2016. Green information, green certification and consumer perceptions of remanufactured automobile parts. Resources, Conservation & Recycling 128: 187–96. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Yacan, Benjamin T. Hazen, and Diane A. Mollenkopf. 2018. Consumer value considerations and adoption of remanufactured products in closed-loop supply chains. Industrial Management and Data Systems 118: 480–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, Valarie A. 1988. Consumer Perceptions of Price, Quality and Value: A Means-end Model and Synthesis of Evidence. Journal of Marketing 52: 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zott, Chris, Raffi H. Amit, and Lorenzo Massa. 2011. The Business Model: Recent Developments and Future Research. Journal of Management 37: 1019–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).