Intrahousehold Relations and Environmental Entitlements of Land and Livestock for Women in Rural Kano, Northern Nigeria

Abstract

1. Introduction

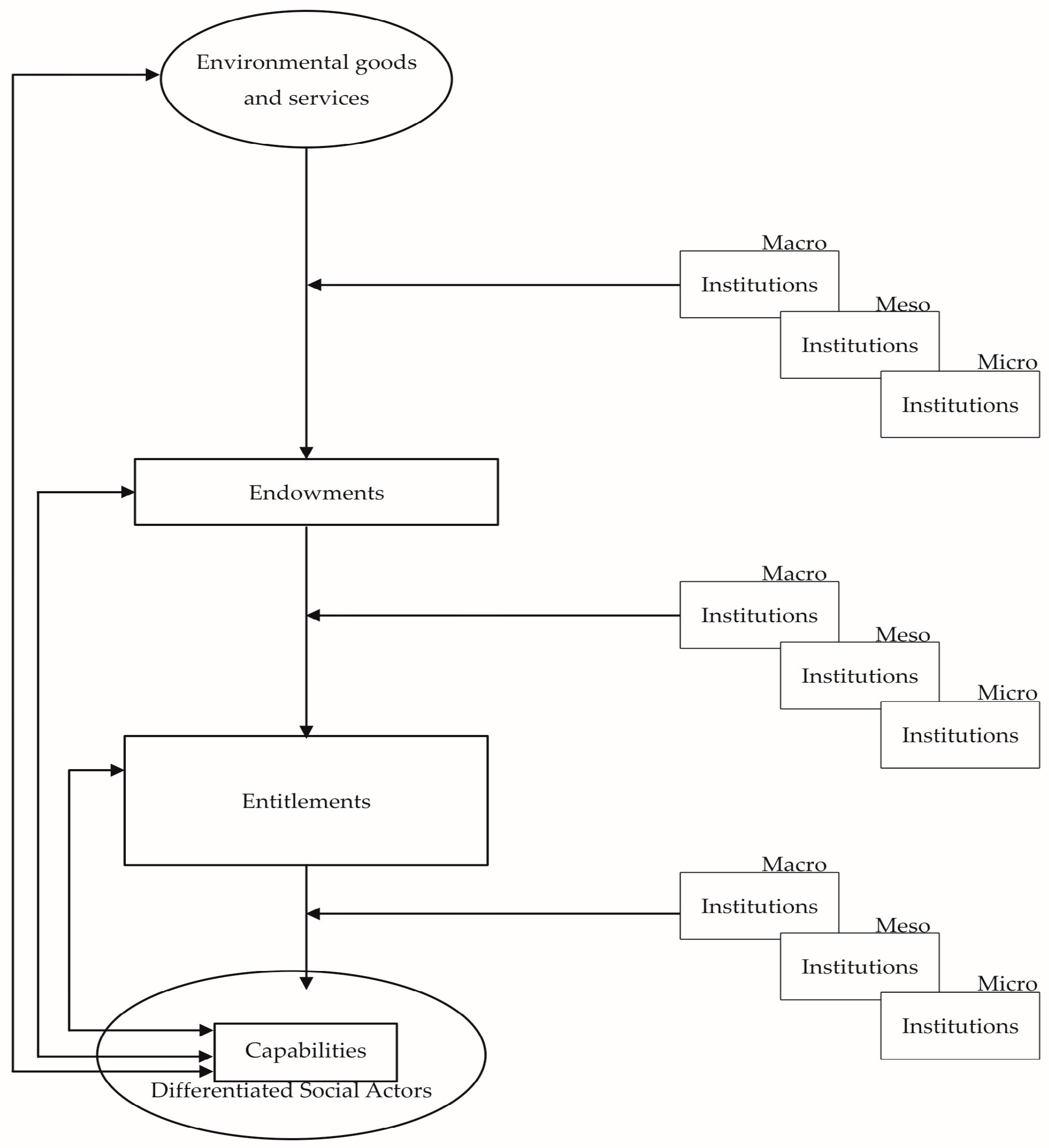

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area in Context

2.2. Research Methods

- Separate in-depth interviews with female and male members of the household: participants were asked about demographic information, land, and tree ownership and use, cultivation practices, labour use, livestock numbers and types, household decision making, and sharing and allocation of resources

- Oral histories of the women

- Transect walks

- Timelines detailing roles and responsibilities of men and women in agricultural production

3. Results and Discussion

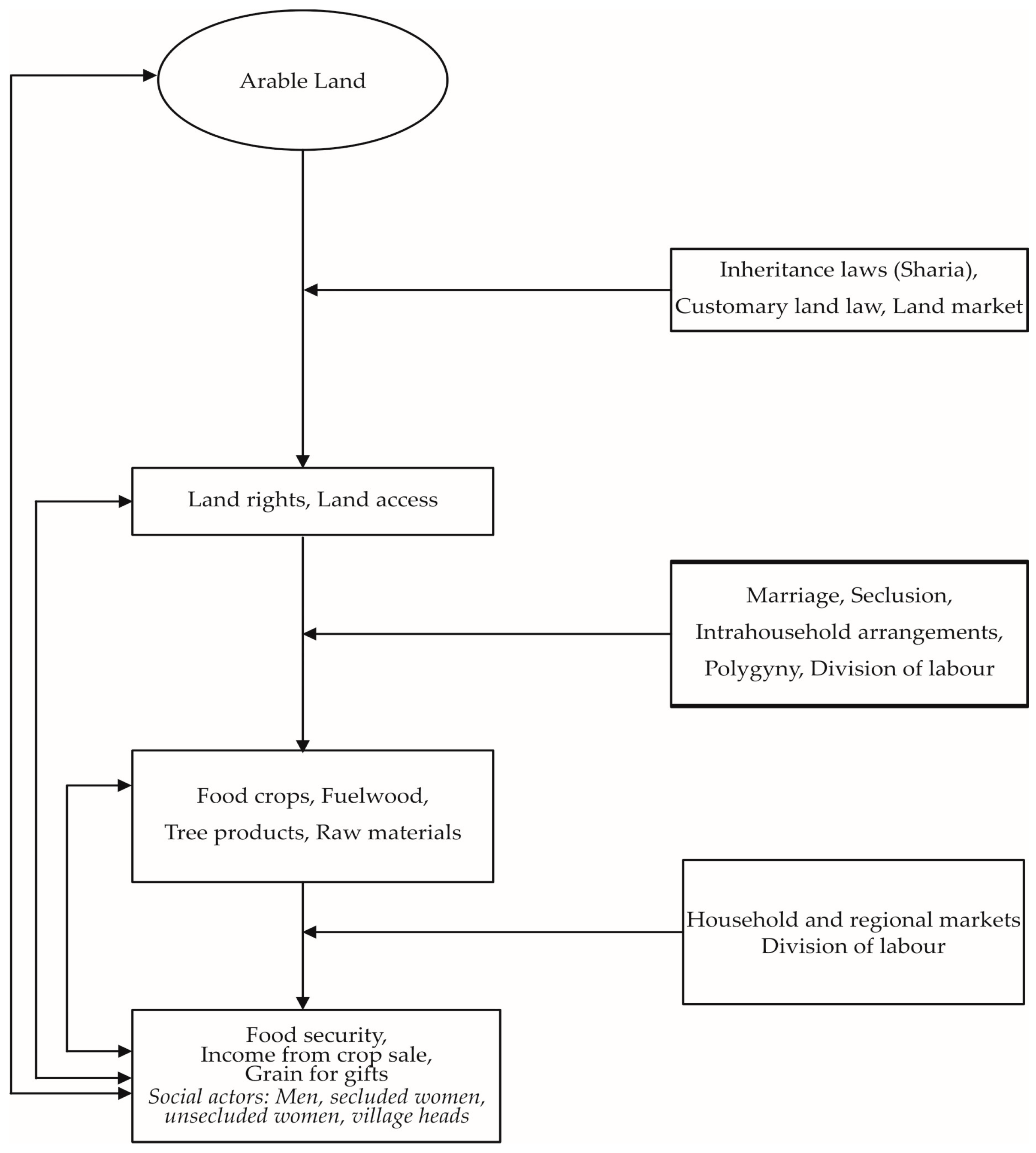

3.1. Environmental Entitlements: Land

I bought a farm 5 years ago from a man in the village who had put it on the market. My husband asked if I wanted to rent it out and share the yield, but I declined. I prefer to do it on my own. I don’t farm myself,I pay others to do it, but the yield is all mine.(Ladi-Secluded)

‘Some we eat, some we sell, and some we give as gifts’(Binta-Unsecluded)

andI have kuka, mangwaro and dorawa trees on my farm. The men chop off any large branches, dry them and bring home for us to use. I don’t sell my fruits but some people do. I make daddawa from the locust bean fruit and use the kuka leaves for soup. I use grain stalk and fuelwood for cooking. It’s my husband’s job to provide fuelwood, though I also contribute from my trees.(Hadiza-Secluded)

I do not own the trees on the land that I borrowed, they belong to my husband and he brings the wood home for our use. He cuts the tree branches and pay for them to be chopped, and then piles them in the house. I eat the fruits whenever I want and the trees provide me with shade.(Zulai-Unsecluded)

I own my own farm, I inherited it them from my father. When he died his farms were shared out amongst us. So I gave the farms out to my uncles to farm, because I can’t do it myself and all my children are in school. I have one I kept for myself and I take care of my children’s schooling needs with it. I don’t give my uncles any money or resources to farm. The arrangement is that they use my land and give me a third of the yield. I have many trees on my farms. Even the trees on the farms that my uncles use belong to me, and I use the fruits as I wish.(Hansatu-Secluded)

I work with my co wife to farm, we cooperate. Sometimes we put money together and borrow a farm and plant on the farm, for example our rice farm in Kura. The farms we have here in the village are separated, we borrowed them from our husband, the one behind our house is mine and hers is in front. We have another farm here that we bought together, a man in the village was going to marry off one of his daughters and we put money together and bought it, and then divided it into two.(Hauwa-Secluded)

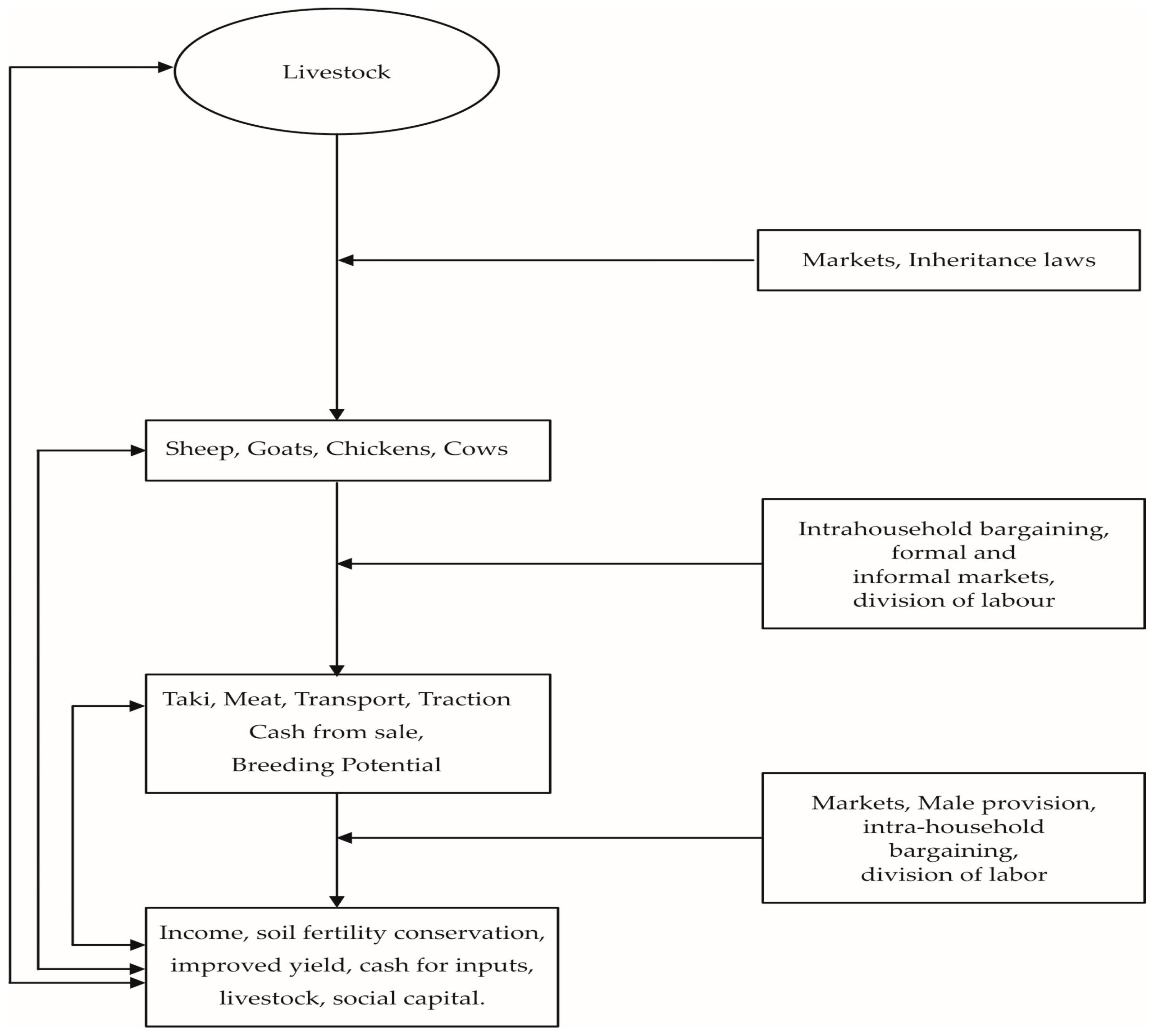

3.2. Environmental Entitlements: Livestock

We have sheep and goats in this house. Some belong to my husband, some to me and some to my sons and their wives. But the taki is for my husband, because that is what we do here. We cannot practice what is not our custom.(Gambo-Unsecluded)

The taki is for the man of the house… he is the one feeding the house isn’t he? Taki is for the maigida (head of the house). It doesn’t matter who the animals belong to, the taki is for the maigida.(Aisha-Secluded)

3.3. Markets

When I want to sell my crops, my husband gives a trusted person to take to the market, and my money is brought to me, after he takes a commission.(Hansatu-Secluded)

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fisher, J.A.; Patenaude, G.; Meir, P.; Nightingale, A.J.; Rounsevell, M.D.; Williams, M.; Woodhouse, I.H. Strengthening conceptual foundations: Analysing frameworks for ecosystem services and poverty alleviation research. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 1098–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacGregor, S. Gender and environment; an introduction. In Routledge Handbook of Gender and Environment; MacGregor, S., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rocheleau, D.; Thomas–Slayter, B.; Wangari, E. Gender and environment: A feminist political ecology perspective. In Feminist Political Ecology: Global Issues and Local Experience; Rocheleau, D., Thomas-Slayter, B., Wangari, E., Eds.; Gender Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Rocheleau, D.; Edmunds, D. Women, men and trees: Gender, power and property in forest and agrarian landscapes. World Dev. 1997, 25, 1351–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dankelman, I.; Jansen, W. Gender, environment, and climate change: Understanding the linkages. In Gender and Climate Change: An Introduction; Dankelman, I., Ed.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2010; pp. 21–54. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, E.R.; Thompson, M.C. Gender and climate change adaptation in agrarian settings: Current thinking, new directions, and research frontiers. Geogr. Compass 2014, 8, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunan, F. Understanding Poverty and the Environment: Analytical Frameworks and Approaches; Routledge: Abingdon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rocheleau, D. Gender, ecology, and the science of survival: Stories and lessons from Kenya. Agric. Hum. Values 1991, 8, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, B. The Gender and Environment Debate-Lessons from India. Fem. Stud. 1992, 18, 119–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C. Gender Analysis of Land: Beyond Land Rights for Women? J. Agrar. Chang. 2003, 3, 453–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, R.; Jackson, C. Introduction: Interrogating development. Feminism, gender and policy. In Feminist Visions of Development: Gender Analysis and Policy; Jackson, C., Pearson, R., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1998; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Nightingale, A. The nature of gender: Work, gender, and environment. Environ. Plan D 2006, 24, 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doss, C.; Kovarik, C.; Peterman, A.; Quisumbing, A.; Mara Bold, M. Gender inequalities in ownership and control of land in Africa: Myth and reality. Agric. Econ. 2015, 46, 403–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinzen-Dick, R.; Nancy Johnson, N.; Quisumbing, A.; Njuki, J.; Behrman, D.; Amber Peterman, A.; Waithanji, A. The gender asset gap and its implications for agricultural and rural development. In Gender in Agriculture; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 91–115. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, C. Men’s Work, Masculinities and Gender Divisions of Labour. J. Dev. Stud. 1999, 36, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kevane, M. Gendered production and consumption in rural Africa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 12350–12355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, M. Gender and the environment: Traps and opportunities. Dev. Pract. 1992, 2, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsikata, D. Gender, Land Tenure and Agrarian Production Systems in Sub-Saharan Africa. Agrar. South J. Political Econ. 2016, 5, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, E.R. Men’s crops and women’s crops: The importance of gender to the understanding of agricultural and development outcomes in Ghana’s central region. World Dev. 2008, 36, 900–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, M.; Udry, C. The Profits of Power: Land Rights and Agricultural Investment in Ghana. J. Political Econ. 2008, 116, 981–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanamuto, N.J.; Hall, S.J. Gender equality, resilience to climate change, and the design of livestock projects for rural livelihoods. Gend. Dev. 2015, 23, 515–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristjanson, P.; Waters-Bayer, A.; Johnson, N.; Tipilda, A.; Baltenweck, I.; Grace, D.; MacMillan, S. Livestock and Women’s Livelihoods. In Gender in Agriculture; Quisumbing, A., Meinzen-Dick, R., Raney, T., Croppenstedt, A., Behrman, J., Peterman, A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 209–233. [Google Scholar]

- Herrero, M.; Grace, D.; Njuki, J.; Johnson, N.; Enahoro, D.; Silvestri, S.; Rufino, M.C. The roles of livestock in developing countries. Animal 2013, 7, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poole, N.; Audia, C.; Kaboret, B.; Kent, R. Tree products, food security and livelihoods: A household study of Burkina Faso. Environ. Conserv. 2016, 43, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boserup, E. Women’s Role in Economic Development; George Allen & Unwin: London, UK, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Callaway, B.J. Ambiguous Consequences of the Socialisation and Seclusion of Hausa Women. J. Mod. Afr. Stud. 1984, 22, 429–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schildkrout, E. Dependence & Autonomy: The Economic Activities of Secluded Hausa Women in Nigeria. In Female & Male in West Africa; Oppong, C., Ed.; George Allen & Unwin: London, UK, 1983; pp. 107–126. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, C. Resolving risk? Marriage and creative conjugality. Dev. Chang. 2007, 38, 107–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, P. Hidden Trade in Hausaland. In Man; JSTOR: New York, NY, USA, 1969; pp. 392–409. [Google Scholar]

- Mack, B. “Royal Wives in Kano”. In Hausa Women in the Twentieth Century; Coles, C., Mack, B., Eds.; University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Environmental Entitlements: A Framework for Understanding the Institutional Dynamics of Environmental Change. Available online: http://dlc.dlib.indiana.edu/dlc/bitstream/handle/10535/3716/Leach-et-al-environment_entitlements_a_framework_for_understanding_the_institutional_dynamics_of_environmental_change.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 1 January 1997).

- Sen, A. “Rights and capabilities”. In Resources, Values and Development; Sen, A., Ed.; Basil Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1984; pp. 307–324. [Google Scholar]

- Leach, M.; Mearns, R.; Scoones, I. Environmental Entitlements: Dynamics and Institutions in Community-Based Natural Resource Management. World. Dev. 1999, 27, 225–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribot, J.C.; Peluso, N.L. A theory of access. Rural Soc. 2003, 68, 153–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringer, L.C. Testing the orthodoxies of land degradation policy in Swaziland. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, S.U. Mediated by Men: Environmental Change, Land Resources Management & Gender in Rural Kano, Northern Nigeria. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK, July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Maconachie, R. Urban Growth and Land Degradation in Developing Cities: Change and Challenges in Kano, Nigeria; Aldershot: Ashgate, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Orchard, S.E.; Stringer, L.C.; Quinn, C.H. Environmental Entitlements: Institutional influence on mangrove social-ecological systems in Northern Vietnam. Resources 2015, 4, 903–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntshona, Z.; Kraai, M.; Kepe, T.; Saliwa, P. From land rights to environmental entitlements: Community discontent in the ‘successful’ Dwesa-Cwebe land claim in South Africa. Dev. South. Afr. 2010, 27, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikor, T.; Nguyen, T.Q. Why may forest devolution not benefit the rural poor? Forest entitlements in Vietnam’s central highlands. World. Dev. 2007, 35, 2010–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makalle, A.M.P. Gender relations in environmental entitlements: Case of coastal natural resources in Tanzania. Environ. Nat. Resour. Res. 2012, 2, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunan, F. Empowerment and institutions: Managing fisheries in Uganda. World Dev. 2006, 34, 1316–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nightingale, A. Bounding difference: Intersectionality and the material production of gender, caste, class and environment in Nepal. Geoforum 2011, 42, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmhirst, R. Introducing new feminist political ecologies. Geoforum 2011, 42, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, A. I’m hungry mum: The politics of domestic budgeting. In Of Marriage and the Market: Women’s Subordination in International Perspective; Young, K., Wolkowitz, C., MCcullagh, R., Eds.; CSE Books: London, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Living with Uncertainty: Gender, Livelihoods and Pro-Poor Growth in Rural Sub-Saharan Africa. Available online: http://www.ids.ac.uk/publication/living-with-uncertainty-gender-livelihoods-and-pro-poor-growth-in-rural-sub-saharan-africa (accessed on 1 January 2001).

- Jackson, C. Introduction: Marriage, Gender Relations and Social Change. J. Dev. Stud. 2012, 48, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S. ‘We don’t have this is mine and this is his’: Managing money and the character of conjugality in Kenya. J. Dev. Stud. 2017, 53, 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortimore, M.; Harris, F. Do small farmers’ achievements contradict the nutrient depletion scenarios for Africa? Land Use Policy 2005, 22, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, F.M.A. Farm-level assessment of the nutrient balance in northern Nigeria. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 1998, 71, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cline-Cole, R. Knowledge claims and landscape: Alternative views of the fuelwood-degradation nexus in northern Nigeria. Environ. Plan. D 1998, 16, 311–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, D.; Lehmann, J.; Fraser, J.A.; Leach, M.; Amanor, K.; Frausin, V.; Kristiansen, S.M.; Millimouno, D.; Fairhead, J. Indigenous African soil enrichment as a climate-smart sustainable agriculture alternative. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2016, 14, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortimore, M. Managing soil fertility on small family farms in African drylands. In Biological Approaches to Sustainable Soil Systems; Uphoff, N., Ball, A.S., Fernandes, E., Herren, H., Husson, O., Laing, M., Palm, C., Pretty, J., Sanchez, P., Sanginga, N., Eds.; CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006; pp. 373–390. [Google Scholar]

- Robson, E. Wife Seclusion and the Spatial Praxis of Gender Ideology in Nigerian Hausaland. Gend. Place Cult. 2000, 7, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, E. The Kitchen as Women’s Space in Rural Hausaland, Northern Nigeria. Gend. Place Cult. 2006, 13, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essiet, E.U. Agricultural sustainability under small-holder farming in Kano, northern Nigeria. J. Arid Environ. 2001, 48, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortimore, M. Overcoming Variability and Productivity Constraints in Sahelian Agriculture. In Politics, Property and Production in the West African Sahel: Understanding Natural Resources Management; Benjaminsen, T.A., Lund, C., Eds.; Nordic African Institute: Uppsala, Norway, 2001; pp. 233–254. [Google Scholar]

- Mortimore, M.J.; Adams, W.M. Farmer adaptation, change and ‘crisis’ in the Sahel. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2001, 11, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, S. Farmers and “Prostitutes”: Twentieth-Century Problems of Female Inheritance in Kano Emirate, Nigeria. J. Afr. Hist. 2003, 44, 463–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, G.; Dwyer, C. Qualitative Methods: Are You Enchanted or Are You Alienated? Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2007, 31, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buscatto, M. Using ethnography to study gender. In Qualitative Research; Silverman, D., Ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2011; pp. 35–51. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, P.J. Land as a right to membership: Land tenure dynamics in a peripheral area of the Kano close-settled zone. In State, Oil, and Agriculture in Nigeria; Watts, M., Ed.; Institute of International Studies, University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Maconachie, R. Reconciling the mismatch: Evaluating competing knowledge claims over soil fertility in Kano, Nigeria. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 31, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maconachie, R.; Tanko, A.; Zakariya, M. Descending the energy ladder? Oil price shocks and domestic fuel choices in Kano, Nigeria. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 1090–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamu, F.L. My wife’s tongue delivers more punishing blows than Muhammed Ali’s fists. Bargaining power in Nigerian Hausa Society. In Gender in Flux; Murphy, B., Ed.; Boran: Chester, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Solivetti, L.M. Family, Marriage and Divorce in a Hausa Community: A Sociological Model. Afr. J. Int. Afr. Inst. 1994, 64, 252–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imam, A. If You Won’t Do These Things for Me, I Won’t Do Seclusion for You’: Local and Regional Constructions of Seclusion Ideologies and Practices in Kano, Northern Nigeria. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Sussex, Brighton, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Meagher, K. Veiled conflicts: Peasant differentiation, gender and structural adjustment in Nigerian Hausaland. In Disappearing Peasantries? Rural Labor in Africa, Asia and Latin America; Bryceson, D.F., Kay, C., Mooij, J., Eds.; IT Publications: London, UK, 2000; pp. 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Kabeer, N. Resources, agency, achievements: Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Dev. Chang. 1999, 30, 435–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Laughlin, B. A Bigger Piece of a Very Small Pie: Intrahousehold Resource Allocation and Poverty Reduction in Africa. Dev. Chang. 2007, 38, 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, B. Conceptualising environmental collective action: Why gender matters. Camb. J. Econ. 2000, 24, 283–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doss, C. Intrahousehold bargaining and resource allocation in developing countries. World Bank Res. Obs. 2013, 28, 52–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, L.; Hoddinott, J.; Alderman, H. Intrahousehold Resource Allocation in Developing Countries; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kevane, M.; Gray, L.C. A Woman’s Field Is Made at Night: Gendered Land Rights and Norms in Burkina Faso. Fem. Econ. 1999, 5, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akresh, R.; Chen, K.; Moore, C. Productive efficiency and the scope for cooperation in polygynous households. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2012, 94, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quisumbing, A.R.; Rubin, D.; Manfre, C.; Waithanji, E.; van den Bold, M.; Olney, D.; Meinzen-Dick, R. Gender, assets, and market-oriented agriculture: Learning from high-value crop and livestock projects in Africa and Asia. Agric. Hum. Values 2015, 32, 705–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C. Conjugality as Social Change: A Zimbabwean Case. J. Dev. Stud. 2012, 48, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Gender and Cooperative Conflicts. In Persistent Inequalities: Women and World Development; Tinker, I., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Quisumbing, A.; Maluccio, J. Resources at marriage and intrahousehold allocation: Evidence from Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Indonesia, and South Africa. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 2003, 65, 283–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njuki, J.; Kaaria, S.; Chamunorwa, A.; Chiuri, A. Linking smallholder farmers to markets, gender and intra-household dynamics: Does the choice of commodity matter? Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2011, 23, 426–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participants | Inheritance | Borrow/Rent | Purchase | Pledge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 20 | 5 | 3 | 1 |

| Women | ||||

| Secluded | 2 | 9 | 3 | 1 |

| Unsecluded | 2 | 12 | 1 | 0 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Umaru Baba, S.; Van der Horst, D. Intrahousehold Relations and Environmental Entitlements of Land and Livestock for Women in Rural Kano, Northern Nigeria. Environments 2018, 5, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments5020026

Umaru Baba S, Van der Horst D. Intrahousehold Relations and Environmental Entitlements of Land and Livestock for Women in Rural Kano, Northern Nigeria. Environments. 2018; 5(2):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments5020026

Chicago/Turabian StyleUmaru Baba, Saadatu, and Dan Van der Horst. 2018. "Intrahousehold Relations and Environmental Entitlements of Land and Livestock for Women in Rural Kano, Northern Nigeria" Environments 5, no. 2: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments5020026

APA StyleUmaru Baba, S., & Van der Horst, D. (2018). Intrahousehold Relations and Environmental Entitlements of Land and Livestock for Women in Rural Kano, Northern Nigeria. Environments, 5(2), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments5020026