Vicarious Posttraumatic Growth in Peer-Support Specialists: An Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

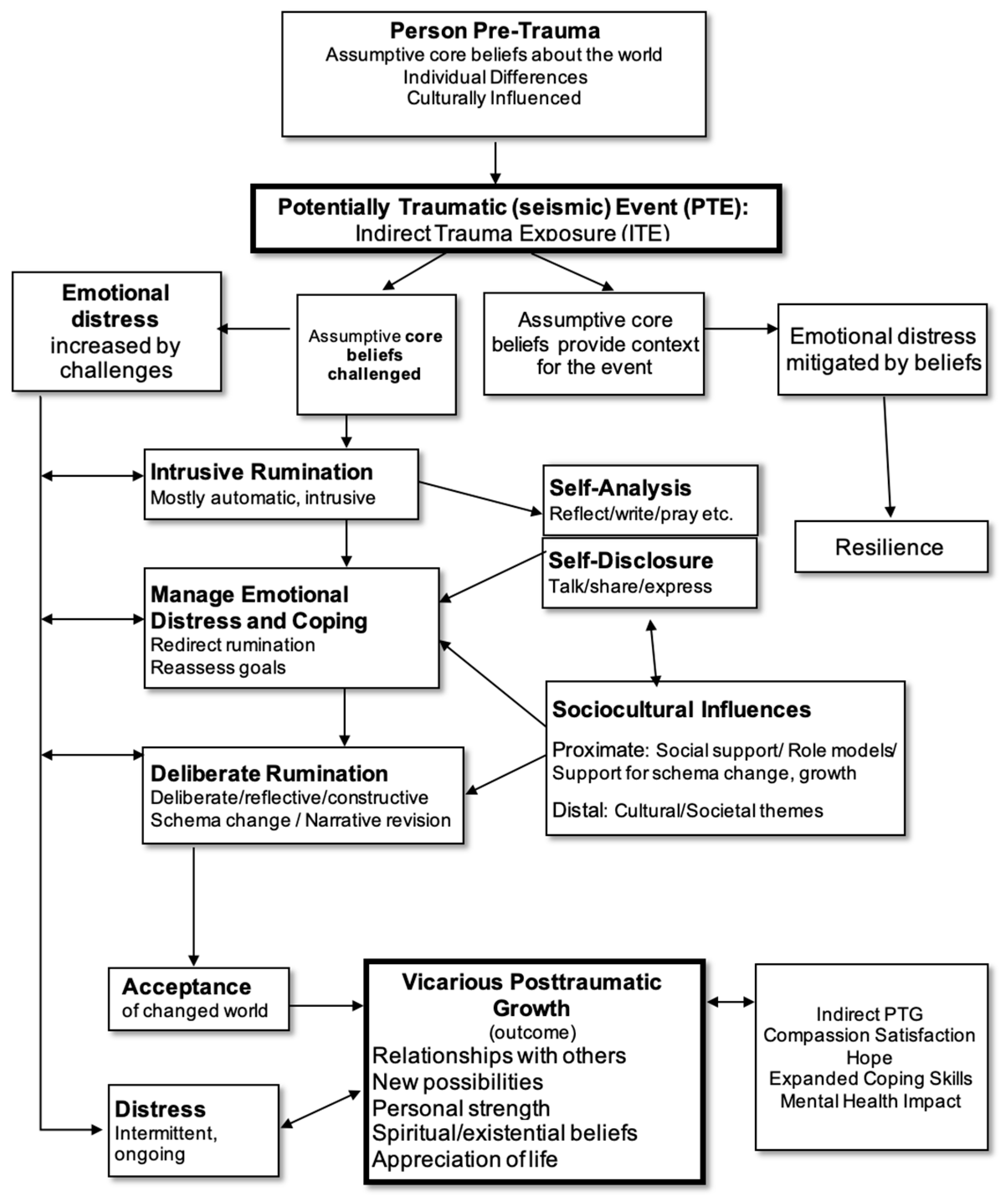

1.1. Theoretical Background

1.2. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Participant Recruitment and Selection

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. VPTG Process Themes

- Superordinate Theme 1. Trigger Events for Vicarious Posttraumatic Growth (VPTG)

Hearing these stories called on the stories that I hadn’t thought about or processed myself and their grief or pain connected with my very real grief and pain.(6)

To see women that were violated in that way, it still hurts me. (6) Anything that had to do with having the innocence taken away from a child or like verbal and emotional abuse, abandonment, stuff like that. Because those were things that I had never really addressed. Maybe in like small doses… when I’d hear those things, it would just kind of take me into that place. (4)

It became, I would say, morally challenging…So I shifted from this, “Holy sh*t. I can’t believe I’m hearing this. I feel so bad for this person.” And then it became, “Wow, what’s really going on in the world?”(5)

- Superordinate Theme 2. Distressing Internal Responses

“So there has been a few times during the struggle portion where I kind of found myself zoning off in their story and started reflecting on my own. One of them even brought back the smells, because that’s all he was talking about. And it took me a couple of days to stop thinking about it to where I wasn’t actually smelling those smells again”. (10) “I had a set of severe nightmares that happened for a two week period…it was like this two week period where I was like, ‘Oh my God. I don’t know if I can do this job if this is what was going to happen’” (1)

“That’s probably the main thing…unwanted thoughts. (6) It would trigger memories of events that I either hadn’t thought of for years and years…I was having intrusive thoughts. It was taking me back to times and places that I didn’t want to revisit”. (1)

- Superordinate Theme 3. VPTG-Oriented Internal Responses

- (a)

- Growing Self-Awareness. A growing self-awareness of internal distress was triggered by hearing stories of trauma from program participants. One participant disclosed,“There are moments that sort of tug at me, but… my practices of regulation have gotten so much stronger so I can identify, ‘Hey, I know what this is. This is some anxiety rolling in.’”(7)

- (b)

- Introspection-Focused Action. Participants noted an evolving ability to use this self-awareness of distress as a cue to engage in introspective activities. For example,“I did not expect this kind of emotional reaction. So, what I’ve essentially done is investigated that. It’s not something that I set aside anymore or push down or deny. It’s something that I investigate. I sit with it, and I have what I call a curiosity journal. I’ll pull that out and start writing down what emotions I’m dealing with and why am I having those emotions”(1)

“Before [being a peer-support specialist] I would just kind of put the mask on, continue about my day and continue just pile on myself in my rucksack and just forgetting about it. Now, I know it’s not okay to do that. So…I’m more open to having that talk with someone if I need to have that talk with someone”.(10)

“A lot of times at the end of the day when I go back to my room, I’ll do a meditation or I will do a breathing exercise or something if I’m feeling really heavy from the day so that I’m not carrying that into the next day.(3)

- (a)

- Deeper Self-Reflection“There was one particular class, a female class, where a lot of things really hit home for me. Even though I was kind of processing things throughout the week, I had made some notes for myself. Like, ‘When you get home, you need to deep dive into these things.’ So I took some time during those two days to really deep dive and process those emotions… I used that time to really dissect those emotions too. (3) We teach ‘the cave to fear to enter holds the treasure you seek.’ Every month I’m going into my cave and I’m looking at something different and sharing that with students…in order to help someone who’s struggling, I have to get into my cave. I can’t give them wisdom if I don’t go in there”. (2)

- (b)

- Schema ChangeParticipants described how entering their metaphorical cave allowed them to deliberately reflect on their internal world and change their own deeply held schemas. Examples of participants’ changed worldviews are,“It’s [working with trauma survivors] opened my eyes to hundreds of new perspectives on hundreds of different things that I’ve experienced in my life, which has helped me kind of make sense of those things. (1) One of the core beliefs that I’ve always maintained from the time I was a child is that we can change the world. And…in order for…it to happen on an individual basis. The change has to happen on an individual basis. And so, do I believe we can change the world? I do, but no longer as simple as I believed it could be. So that’s a core belief that has changed”. (6)

“I see how bad life can be. I see how evil humans can be. How hurtful humans can be. And then watching them change and grow gives me…every [program]…gives me a newfound appreciation for life for the large and small things in life”.(8)

- Superordinate Theme 4. Positive Sociocultural Influences

“Being in a safe and trusting environment where I’ve got [other staff members] that I trust implicitly—and they do the same with me and we create an environment for the students as well—allows me to, I don’t know, dig into some of those emotions that I would have previously ran away from. (1) I feel like building that safe and trusting environment is just as important for the [staff members] as it is for the students”. (3)

- Superordinate Theme 5. Acclimation and Thriving Period

“I think in the beginning, my biggest symptom was that I would be emotionally exhausted after program because there was a lot of things that I would think about… My first couple of classes, I definitely needed more time to recover from those things because I just felt just physically, mentally, emotionally drained from those things”.(9)

“So in the beginning it was difficult, it was harder than it is now for me”. (5) Now, any time something arises for me, that doesn’t go away, I’m talking about it, I’m writing it down, I’m crying about it. I’m addressing it, I’m doing what I can to process it so that it doesn’t cause me to go sit down again. And so as I hear trauma survivors today, it doesn’t call back out my own trauma. Those experiences are there. I remember them, but it’s not as palpable. I don’t feel it within myself as much as I did”. (6)

3.2. VPTG Outcomes Themes

- Superordinate Theme 6. Vicarious Posttraumatic Growth.

“I have a choice when I have a struggle, when you tell me something that strikes something within me, I now have an opportunity to grow …. That doesn’t mean it’s not going to hurt because much of it is going to hurt. But if I approach it from a place that says what’s available for me to take away from this…what’s available to glean from it. (7) I can’t put a finger on it. I think it’s not always one trauma but a death by a thousand cuts. I think growth by a thousand little seeds planted through a thousand different people for sure”. (2)

“… understanding why I’m feeling the emotions that I’m feeling, and then starting to process through those have led to conversations with my family and deepening a relationship with my mother, for example, who I didn’t speak to for years because I’m able to understand a little bit better what she was dealing with at the time. (1) It has helped me be able to be more transparent and more honest with other people, especially when it comes to my needs”. (3)

“We do hear a whole mix of different things that people have experienced. And I just think that… well again, it goes back to the appreciate appreciation for life for me. Just appreciating what I’ve had in my lifetime that maybe someone else didn’t”.(11)

“There’s something that is happening with me in the way of spiritual existential change. I’m not a religious person by nature … That’s just not where I’m at. But as I watch participants come through, I find myself sort of getting hung on where they’re connecting to this universe and what they’re seeing is bigger than themselves. It’s an interesting concept to me. (7) Just watching that process happen each month is something that is no longer a question of “maybe” or “A few of us on Earth has this potential,”—it’s we all have the potential to separate our experiences from our actual spirit and ourselves. And that spiritual and existential change is how I understand it. Like you’re beginning to hold on to more of what you are or your being and less of what you’re being has gone through”. (6)

“As I see them [the participants] grow and get stronger, I get stronger myself. Because I see that you can live through something so traumatic, so horrific. …just because I have the symptoms doesn’t mean that I don’t have inner strength. In fact, my ability to manage to live with those symptoms is an example of my inner strength”.(5)

“I get to see the contrast of what life could be or was for me at some point in time and really take stock of where I’m at today. Each program I come up with new goals for my future. I come up with ways that life could be better if I make simple decisions or changes each day. (6) And a lot of that is this from the conversations that I’m having with the students, where “Hey, I’m really struggling with this. What’s your take on this subject?” Those conversations lead to questions about myself and about my life and different avenues or ways that I can continue to grow on my journey”. (1)

- Superordinate Theme 7. Associated Outcomes.

“In a way it’s exciting because I know that on the other side of that trauma is something beautiful, something amazing. And getting to watch that grow and flourish and develop over even seven days”.(8)

“Being able to work with individuals to see their own self-worth to be able to see that they’ve got control and power to make significant change in their lives. I really wish I could find another word except rewarding, but that’s really what it is”.(1)

“now I see hope. Like when I see someone struggling, I know that when they learn how to appropriately struggle or struggle well, that there are going to be…I’m hopeful for them. (5) And so when I look at everything, I look at the totality of it. And to me, there’s such hope and the possibility of a brighter future”. (8)

“I still have certain thoughts and feelings. What’s different now is I don’t react to them… So is it okay to get angry? Yes. Is it okay to be anxious about certain things? Yeah, absolutely. Everybody gets those things…but my response is much different than how I used to react before. It’s tremendously different.”(9)

“I really do feel free. Not only from what I used to carry, but from the fear that something else will happen and that I’ll have to carry that all over again. I know the process of healing or getting myself out of that. (6) It’s made me healthier than I would have been otherwise… The clarity that I have on how our minds work and the things we tell ourselves and how those affect our thoughts and actions.” (5)

4. Discussion

4.1. The VPTG Process

- Trigger Events for VPTG—Indirect Trauma Exposure (ITE) presented challenges to core beliefs about the self, others, and the world, initiating the process of VPTG.

- Distressing Internal Responses—Exposure to ITE and associated challenges to core beliefs caused emotional distress (e.g., anxiety, sadness, nightmares) and intrusive thoughts, which together can take the form of symptoms of ST.

- VPTG-Oriented Internal Responses—As individuals navigated distress, VPTG-Oriented Internal Responses emerged, characterized by self-analysis, self-disclosure, emotional regulation practices, deliberate rumination, and ultimately, acceptance of the way things had changed, including acceptance of positive changes in the aftermath of trauma.

- Positive Sociocultural Influences—These cognitive and emotional shifts were promoted by the presence of trust and emotional safety in relationships which provided a foundation for processing internal distress and integrating new insights.

- Acclimation and Thriving Period—Participants described that, over time, they became more able to tolerate the emotional demands of working with trauma survivors and to engage more intentionally in their own growth and thriving as a result of indirect trauma exposure. The researchers characterized this progression as a shift from an “Acclimation Period”, marked by frequent and intense distress, to a “Thriving” period, characterized by increased capacity for constructive, growth-oriented practices and less overwhelming distress.

4.2. VPTG Outcomes

5. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abu-Sharkia, S., Taubman-Ben-Ari, O., & Mofareh, A. (2020). Secondary traumatization and personal growth of healthcare teams in maternity and neonatal wards: The role of differentiation of self and social support. Nursing & Health Sciences, 22(2), 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrington, A. J., & Shakespeare-Finch, J. (2012). Working with refugee survivors of torture and trauma: An opportunity for vicarious post-traumatic growth. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 26(1), 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaton, J. D., Ohrt, J. H., Linich, K., McCartney, E., & Glascoe, G. (2023). Vicarious posttraumatic growth: A systematic review and thematic synthesis across helping professions. Traumatology, 29(1), 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekel, S., Ein-Dor, T., & Solomon, Z. (2012). Posttraumatic growth and posttraumatic distress: A longitudinal study. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 4(1), 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamama-Raz, Y., Hamama, L., Pat-Horenczyk, R., Stokar, Y. N., Zilberstein, T., & Bron-Harlev, E. (2021). Posttraumatic growth and burnout in pediatric nurses: The mediating role of secondary traumatization and the moderating role of meaning in work. Stress and Health, 37(3), 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamama-Raz, Y., & Minerbi, R. (2019). Coping strategies in secondary traumatization and post-traumatic growth among nurses working in a medical rehabilitation hospital: A pilot study. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 92(1), 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, T., Schmidt, F., & Mushquash, C. (2023). A personal history of trauma and experience of secondary traumatic stress, vicarious trauma, and burnout in mental health workers: A systematic literature review. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 15(S2), S213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z., Doege, D., Thong, M. S., & Arndt, V. (2020). The relationship between posttraumatic growth and health-related quality of life in adult cancer survivors: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 276, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manning-Jones, S., de Terte, I., & Stephens, C. (2015). Vicarious posttraumatic growth: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Wellbeing, 5(2), 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinmäki, S. E., van der Aa, N., Nijdam, M. J., Pommée, M., & Ter Heide, F. (2021). Treatment response and treatment response predictors of a multidisciplinary day clinic for police officers with PTSD. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 15(2), 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Măirean, C. (2016). The relationship between secondary traumatic stress and personal posttraumatic growth: Personality factors as moderators. Journal of Adult Development, 23(2), 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrill, E. F., Brewer, N. T., O’Neill, S. C., Lillie, S. E., Dees, E. C., Carey, L. A., & Rimer, B. K. (2008). The interaction of post-traumatic growth and post-traumatic stress symptoms in predicting depressive symptoms and quality of life. Psychooncology, 17, 948–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogińska-Bulik, N. (2018). Secondary traumatic stress and vicarious posttraumatic growth in nurses working in palliative care—The role of psychological resilience. Postępy Psychiatrii i Neurologii, 27(3), 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pięta, M., & Rzeszutek, M. (2022). Posttraumatic growth and well-being among people living with HIV: A systematic review and meta-analysis in recognition of 40 years of HIV/AIDS. Quality of Life Research, 31(5), 1269–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruini, C., Vescovelli, F., & Albieri, E. (2013). Post-traumatic growth in breast cancer survivors: New insights into its relationships with well-being and distress. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 20, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakespeare-Finch, J., & Lurie-Beck, J. (2014). A meta-analytic clarification of the relationship between posttraumatic growth and symptoms of posttraumatic distress disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiri, S., Wexler, I. D., Alkalay, Y., Meiner, Z., & Kreitler, S. (2008). Positive and negative psychological impact after secondary exposure to politically motivated violence among body handlers and rehabilitation workers. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 196(12), 906–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method, and research. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi, R. G., Shakespeare-Finch, J., & Taku, K. (2018). Posttraumatic growth: Theory, research, and applications. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Tsirimokou, A., Kloess, J. A., & Dhinse, S. K. (2023). Vicarious post-traumatic growth in professionals exposed to traumatogenic material: A systematic literature review. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 24(3), 1848–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufford, L., & Newman, P. (2010). Bracketing in qualitative research. Qualitative Social Work, 11(1), 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willig, C. (2013). Introducing qualitative research in psychology (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill Education. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Greene, T.C.; Rhodes, J.R.; Renner-Wilms, S.; Tedeschi, R.G.; Moore, B.A.; Elkins, G.R. Vicarious Posttraumatic Growth in Peer-Support Specialists: An Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1673. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121673

Greene TC, Rhodes JR, Renner-Wilms S, Tedeschi RG, Moore BA, Elkins GR. Vicarious Posttraumatic Growth in Peer-Support Specialists: An Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1673. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121673

Chicago/Turabian StyleGreene, Taryn C., Joshua R. Rhodes, Skyla Renner-Wilms, Richard G. Tedeschi, Bret A. Moore, and Gary R. Elkins. 2025. "Vicarious Posttraumatic Growth in Peer-Support Specialists: An Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 12: 1673. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121673

APA StyleGreene, T. C., Rhodes, J. R., Renner-Wilms, S., Tedeschi, R. G., Moore, B. A., & Elkins, G. R. (2025). Vicarious Posttraumatic Growth in Peer-Support Specialists: An Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis. Behavioral Sciences, 15(12), 1673. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121673