Self-Perception of Children and Adolescents’ Refugees with Trauma: A Qualitative Meta-Synthesis of the Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1: How do refugee children and adolescents perceive and describe their daily stressors during displacement and post-resettlement?

- RQ2: How are these perceptions influenced by gender, age, and unaccompanied status?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Protocol and Search Strategy

2.3. Selection: Inclusion & Exclusion Criteria

- (a)

- Used a qualitative research design such as semi-structured interviews or focus group or mixed-method studies reporting qualitative data;

- (b)

- Were published in a peer-review journal, and written in English;

- (c)

- Sampled children and adolescents aged 3 to 19 years living in refugee camps or in the advanced phase (resettlements) experiencing aspects of trauma. We chose the age range 3 to 10 to cover definition of childhood and 10 to 19 years to cover WHO definition of adolescents;

- (d)

- Qualitative studies that explored perception of children and adolescents’ traumatic experience of settling in a refugee camp and after (resettlement) auto reported by minors;

- (e)

- Included participants with self-reported depression or PTSD or diagnosed by a health professional, regardless of severity or treatment received. We included studies that involved participants with depression, PTSD, with or without a comorbid anxiety.

- (a)

- Sampled participants above the age of 19;

- (b)

- Qualitative studies that did not provide perspective on children and adolescents trauma but focused on the experience from other sources such as parents, teachers, healthcare professionals, guardians, etc.;

- (c)

- Sampled participants with previous history of depression;

- (d)

- Sampled participants with: a co-morbid chronic physical disability; any co-morbid mental illness (e.g., schizophrenia, personality disorders); or a co-morbid neurocognitive disorder (e.g., autism spectrum). This avoids capturing the experience of trauma settling in a refugee camp or resettlement in the context of co-morbid conditions beyond common mental disorders;

- (e)

- Studies that included quantitative research design or literature review, conceptual articles, commentaries, books, and book chapters;

- (f)

- Studies that focus on studying different contexts other than refugee camp experience (i.e., school context, acculturation, community in a daily basis after resettled);

- (g)

- Studies that were not written in English.

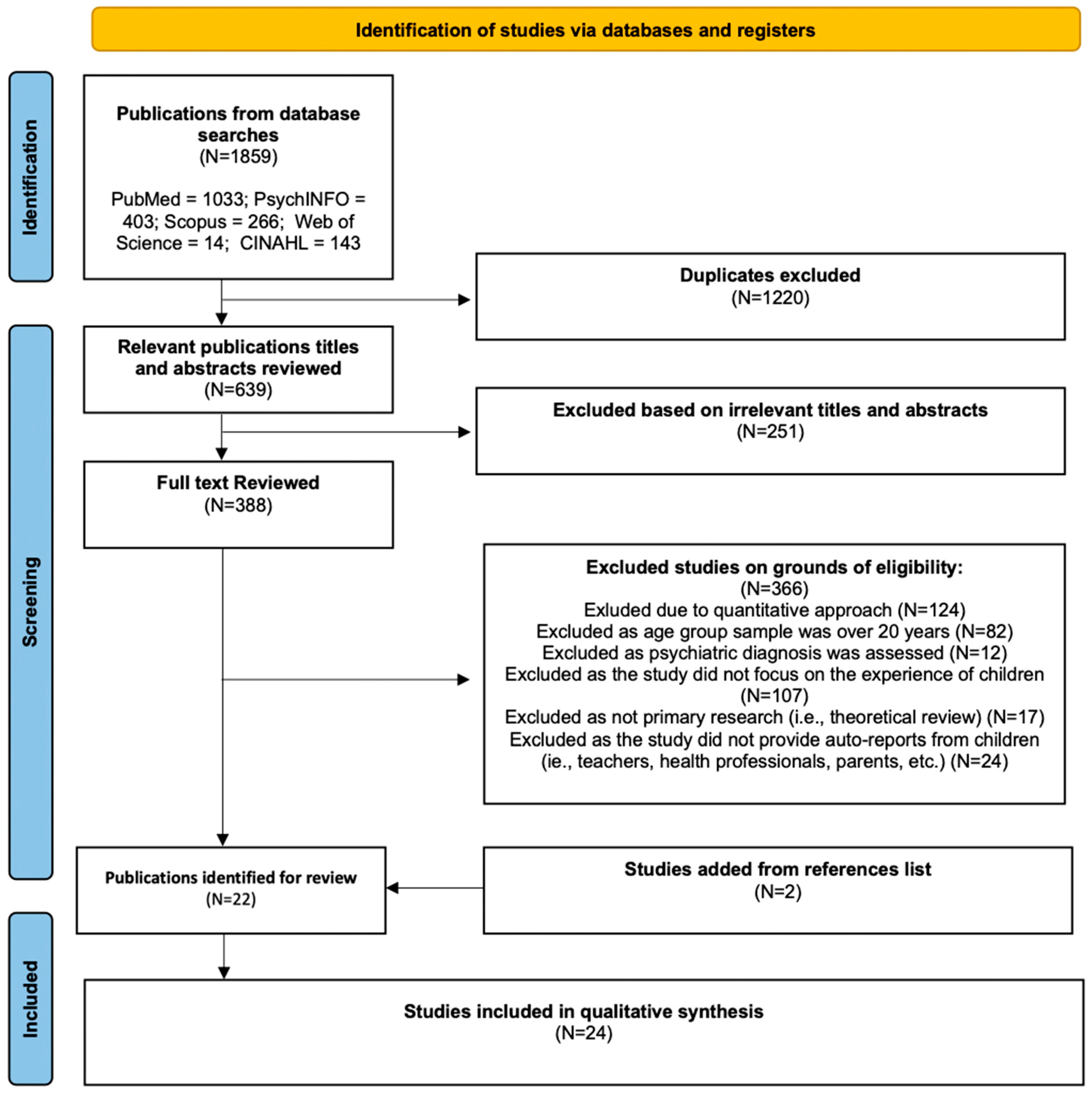

2.4. Data Screening and Extraction

2.5. Quality Appraisal

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Description of Included Studies

3.2. Thematic Synthesis

3.2.1. Theme 1: Perception of Mental Health

‘‘…In some cultures, mental health is not perceived the way that we perceive it in the UK, or America or the Western world. You know, some cultures would just say that you’re a crazy person perhaps, in terms of summing it up. And therefore the stigma associated with that would consequently lead people not to admit it.”

“I have so many problems (…) They [psychologists] always want to talk about my past. If I talk about it, it comes again in my brain, it comes again. In the end, maybe I get crazy. I have so many… I do not want to think about it anymore.”

Subtheme 1.1. Mental Health Literacy

“…they keep talking to you, that means this person annoying you and you just closing your ears.”

“…talks doesn’t helps me because every time I was talking about it, it just reminded me about home and was hurting me about same, same problem and more worse.”.

“(…) They are asking so many questions, and they do not think that, afterwards, I am going to think about my past. My heart becomes disgusting.”

“… especially the society where we come from, children don’t talk a lot. Children are not even allowed to reveal things. Children are not even allowed to talk about being abused.”.

Subtheme 1.2. Fear of Being Judged

“‘…Then I told this lady I’m not crazy, I’m not like these, these, you know…I tell her look my hair, look my clothes, I’m not crazy.’”

“I mean, I don’t really, uh, express myself, so, yeah. Like, I don’t really tell anyone about how I’m feeling and stuff, you know (…) Uh, I just, uh, I don’t trust anybody.”

3.2.2. Theme 2: Stigma Regarding Refugee Status

“When I arrived in Portugal, I felt like a criminal… All that confusion… The cops intimidated me a great deal. They said things to me like: “You’re going back to your country.” They said a lot of things like that… They told me to stay at the detention centre with some women and their children. Some women were my mothers….”

“They don’t want to say to my custodian that my mother is dead. They were hiding it from me. But later I found out that she is dead. That is it and also here, the time I came here, I used to cry all the time, feeling sad so much and sometimes when I cool down then sometimes it comes again. Sometimes it stops but when someone makes trouble with me, then I used to remind all that things that happened before (…).”

“I will neither have a quality profession nor a job. That’s it … Whatever we can find….”

“I want to know if I will be arrested tonight and have to leave this country or if I can sleep without fear for a few extra months. Please let me retain some control over my own life—13 years old child.”

“When we received the papers on [date], we discovered that [sister] was omitted. We knew they were taking her out of our family because she had become an adult. This shocked us.”

“The law says it is not written in my papers to work. So this is why I lost this job and now I need a job if I want to stay in this country. I want for me to pay taxes in Austria, think that it can be possible so please I need help. I need, I want to make work and before I work I need to make school and so that I understand the language that is more important. If I can’t speak the language for me to stay in the country it will be difficult. I must speak their language (…),”

“We lived [several] years in a camp in [country]… If it’s raining …it would pour on us. When the weather is getting hot the tents burn, because of the electricity … the tents were on fire—Iraqi child.”

“I say I want to go out. I want to meet my friends. I want to sleep over with them.‘No, you have to talk to your assigned legal guardian’, who says no, and the social services say you are a child. So I become sad, and I cry, and I do nothing. I keep it to myself.”

3.2.3. Theme 3: The Desire to Belong

“Who I am talking to? Rather to my co-citizens, because they are in the same situation as I am and they understand me better. When I am in the company of a German or someone from another country and when I talk a bit, yes, then she or he understands everything, she can listen to me and hear everything I tell, but she cannot feel with me. When I speak with an Afghan person, he has been in the same situation as I am, he can give me better advice about what I can do, how I can create a good life.”

Subtheme 3.1. Fear of Not Belonging

“My brother is the first person I go to when I have problems or feel bad. I feel stronger with my brothers and sisters…”.

“However, children mostly described missing in- person interactions and were yearning for their relatives.”.

“Here there is no equal chance for the blacks and that really sucks and, and racism is not very good here because to me it’s something that always worries me. No friends and especially living in a country which is not an English-speaking country. Many people speak English here but they are always expecting you to speak their language. Even when you can talk to them in their language, someone just looks at you and starts to run away. Someone even looks at you standing far away from you and would just call the police, say there’s a black man here which is all not good.”.

“with my friends in the community, I am more free. But in school, everyone respects one another. But friends in the community, we mess around and laugh. -16 years old).”.

“Since I came to Turkey young, my Turkish is very good. However, because I dress differently, it is immediately understood that I am Syrian, and they do not want to make friends with me.”

“I have Syrian friends but feel lonely, and nobody understands me!”.

“Friends and family are their support system rather than professionals”.

Subtheme 3.2. Religion as a Coping Mechanism

“God is great! He solves all our problems. When I feel bad, when I feel uneasy, praying and praying comforts me.”

“Religion was significant source of support, distracted them and prevent distress”

“God. Only God. I walked for 5 to 6 days straight, a long time almost without stopping. I no longer felt anything, my feet, my body, nothing. Only God helped. It was because he didn’t want me to die.”

“Before bedtime, we were reading the Quran and praying to stay alive for the next day.”

3.2.4. Theme 4: Gender Needs

“A female physician said: ‘Syrian females are suffering more than males from psychosocial problems, especially because of thoughts of being forced to early marriage’.”

“I was pressured at my parent’s place. I didn’t feel any warm-heartedness from my parents and siblings. When a girl is pressured at her parent’s house, she would choose to get married no matter whom the husband is. My parents pressured me a lot, and they watched my every step. They interfered in everything, and they tried to control me in every way.”

“We don’t have money for food. I want to get married to have a better life. We need money. I need to get married to be able to get what I need.”

“I know a girl who’s 20 years old. She’s been married and divorced three times already and her parents keep marrying her by force for the money. She has one child from the first husband, two children form the second husband and she’s already divorced from the third, but she’s pregnant. He divorced her when she was three months pregnant—Older adolescent girl.”

3.2.5. Theme 5: Discrimination from Others

“Many participants described damaging attacks on their homes (e.g., explosions, gunshots, other acts of war). In post-resettlement narratives, participants also discussed the vandalism of their homes in their new communities as well as discrimination and harassment at the hands of their neighbours. One participant specifically talked about how someone threw a rock at the participant’s house.”(p. 497)

“Once, when I was walking on the street, a 45-year-old man stopped me. He said -You are a Syrian; you don’t pay rent; the state pays you a salary!”

“They call us by names like donkey, foal, shoe, tar and so on—Younger adolescent boy.”

“They didn’t want to see so many Syrian people in [country]. And that’s why we can’t do so many things. For example, this year, when I changed my school, we can’t talk to the [foreign] students. So they think we just have to have a Syrian school. We are separated. And you just think that, we are not normal—Syrian child.”

“I don’t go to school here, and it frustrates me. I was a good student. Now, I’m forgetting everything, all the material, I wish I could go back to school and start learning again.”

4. Discussion

4.1. Practical Implications

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdelhamid, S., Lindert, J., Fischer, J., & Steinisch, M. (2023). Negative and protective experiences influencing the well-being of refugee children resettling in Germany: A qualitative study. BMJ Open, 13(4), e067332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainamani, H. E., Mbwayo, A. W., Mathai, M., Karlsson, L., & Zari Rukundo, G. (2025). Post-traumatic stress disorder and its associated factors: A cross-sectional study among refugee children and adolescents living in a Ugandan refugee settlement. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 16(1), 2494367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shatanawi, T. N., Khader, Y., ALSalamat, H., Al Hadid, L., Jarboua, A., Amarneh, B., Alkouri, O., Alfaqih, M. A., & Alrabadi, N. (2023). Identifying psychosocial problems, needs, and coping mechanisms of adolescent Syrian refugees in Jordan. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1184098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjum, G., Aziz, M., & Hamid, H. K. (2023). Life and mental health in limbo of the Ukraine war: How can helpers assist civilians, asylum seekers and refugees affected by the war? Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1129299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkins, S., Lewin, S., Smith, H., Engel, M., Fretheim, A., & Volmink, J. (2008). Conducting a meta-ethnography of qualitative literature: Lessons learnt. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett-Page, E., & Thomas, J. (2009). Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: A critical review. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 9, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackmore, R., Gray, K. M., Boyle, J. A., Fazel, M., Ranasinha, S., Fitzgerald, G., & Gibson-Helm, M. (2020). Systematic review and meta-analysis: The prevalence of mental illness in child and adolescent refugees and asylum seekers. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(6), 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boeyink, C., Falisse, J. B., Niyokwizera, L., & Ibrahim, K. (2025). Anchors, archipelagos, and ports of departure: How resettlement shapes im/mobilities in Nyarugusu refugee camp, Tanzania. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 48, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bründlmayer, A., Sales, C., Zhang, R., Pien, J., Plener, P. L., Laczkovics, C., & Schwarzenberg, J. (2025). Narrative analysis of interviews conducted with African unaccompanied refugee minors. Journal of Global Health, 15, 04174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Abreu, A., Castro-Olivo, S., Ura, S. K., & Furrer, J. (2021). Hope for the future: A qualitative analysis of the resettlement experience of Syrian refugee adolescents and parents. School Psychology International, 42(2), 132–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, C. M., Watt, H., Michael, S., & Bartels, S. A. (2021). “I don’t know if we’ll ever live in harmony”: A mixed-methods exploration of the unmet needs of Syrian adolescent girls in protracted displacement in Lebanon. Archives of Public Health = Archives Belges de Sante Publique, 79(1), 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeClercq, J., Saad, B., Bazzi, C., Jovanovic, T., Javanbakht, A., & Grasser, L. R. (2025). Transcribed in the nervous system: Semantic elements of trauma narratives are associated with anxiety symptoms in youth resettled as refugees. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 38(3), 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demirli Yıldız, A., & Strohmeier, D. (2024). The role of post-traumatic stress symptoms and post migration life difficulties for future aspirations of Iraqi and Syrian asylum seekers. Sage Open, 14(2), 21582440241244698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EL-Awad, U., Eves, R., Hachenberger, J., Bozorgmehr, K., Entringer, T. M., Hecker, T., Razum, O., Sauzet, O., & Lemola, S. (2025). Post-migration stress mediates associations between potentially traumatic peri-migration experiences and mental health among Middle Eastern refugees in Germany. BMC Public Health, 25, 2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erwin, E. J., Brotherson, M. J., & Summers, J. A. (2011). Understanding qualitative metasynthesis: Issues and opportunities in early childhood intervention research. Journal of Early Intervention, 33(3), 186–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, S. (2008). The psychosocial predisposition effects in second language learning: Motivational profile in Portuguese and Catalan samples. Revista Internacional de Didáctica de las Lenguas Extranjeras—Porta Linguarum, 10, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, S. (2024). Topic modelling and sentiment analysis during COVID-19 revealed emotions changes for public health. Scientific Reports, 14, 24954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, S., Brandão, T., & Nunes, O. (2019). Learning styles determine different immigrant students’ results in testing settings: Relationship between nationality of children and the stimuli of tasks. Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 9(12), 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, S. A. D. B., & Da Silva, C. F. (2009). Cognitive differences in second language learners and the critical period effects. L1-Educational Studies in Language and Literature, 9(4), 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filler, T., Georgiades, K., Khanlou, N., & Wahoush, O. (2021). Understanding mental health and identity from Syrian refugee adolescents’ perspectives. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 19, 764–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gušić, S., Malešević, A., Cardeña, E., Bengtsson, H., & Søndergaard, H. P. (2018). “I feel like I do not exist:” A study of dissociative experiences among war-traumatized refugee youth. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 10(5), 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettich, N., & Meurs, P. (2021). Complex dynamics in psychosocial work with unaccompanied minor refugees with uncertain future prospects: A case study. International Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies, 18(1), 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarlby, F., Goosen, S., Derluyn, I., Vitus, K., & Jervelund, S. S. (2018). What can we learn from unaccompanied refugee adolescents’ perspectives on mental health care in exile? European Journal of Pediatrics, 177, 1767–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, P. (2025). Echoes of the past, lived in the present: A hermeneutic phenomenological inquiry into the impact of forced migration on second-generation children of refugees [Ph.D. dissertation, The George Washington University]. [Google Scholar]

- Khawaja, N. G., & Schweitzer, R. D. (2024). A qualitative study of adolescents from refugee backgrounds living in Australia: Identity and resettlement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(3), 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klim, K. (2025). Caught in the crossfire: Exploring impacts on young adults in Russo-Ukrainian conflict zones [Master’s thesis, Royal Roads University (Canada)]. [Google Scholar]

- Kronick, R., Rousseau, C., & Cleveland, J. (2018). Refugee children’s sandplay narratives in immigration detention in Canada. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 27, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulari, G. (2024). What has love got to do with cyber dating abuse: Indirect effect of attachment style on depressive symptoms. Deviant Behavior, 46(8), 1000–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y. J., & Lee, K. (2018). Group child-centered play therapy for school-aged North Korean refugee children. International Journal of Play Therapy, 27(4), 256–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachal, J., Revah-Levy, A., Orri, M., & Moro, M. R. (2017). Metasynthesis: An original method to synthesize qualitative literature in psychiatry. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 8, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, J. E., Karugahe, W., & Baguma, P. K. (2024). Unpacking gender-specific risk and protective factors for mental health status among Congolese refugees in Uganda. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 15(1), 2334190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavdas, M., Guribye, E., & Sandal, G. M. (2023). “Of course, you get depression in this situation”: Explanatory models (EMs) among Afghan refugees in camps in Northern Greece. BMC Psychiatry, 23(1), 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magan, I. M., Sanchez, E., & Munson, M. R. (2024). “I talk to myself”: Exploring the mental and emotional health experiences of Muslim Rohingya refugee adolescents. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal, 41, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, P. (2019). Exploring stigma and its effect on access to mental health services in unaccompanied refugee children. BJPsych Bulletin, 43(6), 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, P., Vostanis, P., Karim, K., & O’Reilly, M. (2019). Potential barriers in the therapeutic relationship in unaccompanied refugee minors in mental health. Journal of Mental Health, 28(4), 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattelin, E., Söderlind, N., & Korhonen, L. (2024). “You cannot just stop life for just that”: A qualitative study on children’s experiences on refugee journey to Sweden. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 33(9), 3133–3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moleiro, C., & Roberto, S. (2021). The path to adulthood: A mixed-methods approach to the exploration of the experiences of unaccompanied minors in Portugal. Journal of Refugee Studies, 34(3), 3264–3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noblit, G., & Hare, R. (1988). Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Oberg, C., & Sharma, H. (2023). Post-traumatic stress disorder in unaccompanied refugee minors: Prevalence, contributing and protective factors, and effective interventions: A scoping review. Children, 10(6), 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osman, W., Ncube, F., Shaaban, K., & Dafallah, A. (2024). Prevalence, predictors, and economic burden of mental health disorders among asylum seekers, refugees and migrants from African countries: A scoping review. PLoS ONE, 19(6), e0305495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oztabak, M. U. (2020). Refugee children’s drawings: Reflections of migration and war. International Journal of Educational Methodology, 6(2), 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pejic, V., Mehjabin Parr, K., & Ellis, B. H. (2025). Applying the core stressor framework to understand the experiences of refugee children in transition. Psychiatry, 88(3), 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Program CASP. (2018). CASP (qualitative) checklist. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Prospero. (2025). International prospective register of systematic review. Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD420251153819 (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- QSR International Pty Ltd. (2020). NVivo. Available online: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysissoftware/home (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Roupetz, S., Bartels, S. A., Michael, S., Najjarnejad, N., Anderson, K., & Davison, C. (2020). Displacement and emotional well-being among married and unmarried Syrian adolescent girls in Lebanon: An analysis of narratives. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(12), 4543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajdi, J., Essaid, A., Miralles Vila, C., Abu Taleb, H., Abu Azzam, M., & Malachowska, A. (2021). ‘I dream of going home’: Gendered experiences of adolescent Syrian refugees in Jordan’s Azraq Camp. European Journal of Development Research, 33(5), 1189–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santinho, C., & Krysanova, O. (2024). Conducting Research with unaccompanied refugee minors within an institutional context: Challenges and insights. Social Sciences, 13(7), 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharpf, F., Masath, F. B., Mkinga, G., Kyaruzi, E., Nkuba, M., Machumu, M., & Hecker, T. (2024). Prevalence of suicidality and associated factors of suicide risk in a representative community sample of families in three East African refugee camps. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 59(2), 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shohel, M. M. C., Ashrafuzzaman, M., Azim, F., Akter, T., & Tanny, S. F. (2022). Displacement and trauma: Exploring the lost childhood of Rohingya children in the refugee camps in Bangladesh. In Social justice research methods for doctoral research (pp. 244–272). IGI Global. [Google Scholar]

- Sleijpen, M., Mooren, T., Kleber, R. J., & Boeije, H. R. (2017). Lives on hold: A qualitative study of young refugees’ resilience strategies. Childhood, 24(3), 348–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). (2025). Refugees. UNHCR. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/about-unhcr/who-we-protect/refugees (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Van de Wiel, W., Castillo-Laborde, C., Urzúa, I. F., Fish, M., & Scholte, W. F. (2021). Mental health consequences of long-term stays in refugee camps: Preliminary evidence from Moria. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veronese, G., Cavazzoni, F., Jaradah, A., Yaghi, S., Obaid, H., & Kittaneh, H. (2021). Palestinian children living amidst political and military violence deploy active protection strategies against psychological trauma: How agency can mitigate traumatic stress via life satisfaction. Journal of Child Health Care, 26(3), 422–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vossoughi, N., Jackson, Y., Gusler, S., & Stone, K. (2018). Mental health outcomes for youth living in refugee camps: A review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 19(5), 528–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetim, O., Tamam, L., Küçükdağ, R. M., & Sebea Alleil, İ. (2025). “The wind does not go the way the ship wants!”: Stress and social support in Syrian migrant adolescents. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 20(1), 2467514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Search Terms |

|---|

| Block 1: Target group Children* OR schoolchild* OR child* OR young* OR adolescent* OR minor* |

| Block 2: Trauma experience Refugee* OR mental health* OR mood* OR psychological health* OR psychological problem* OR externalizing* OR internalizing* OR recreation* OR positive affect* OR life skill* OR well-being* OR family separation* OR friend support* OR stress* OR anxiety* OR distress* OR loneliness* OR stigma* |

| Block 3: Cognitive and Interpretative responses Perception* OR think* OR understanding* OR narratives* OR perspective* OR attitude* |

| Block 4: Methods Personal narratives* OR qualitative* OR interview* OR focus group* OR thematic analysis |

| Citation/Country | Sample Size/Population | Aim | Data Collection | Analysis | Themes and Content | Quality Appraisal 1–10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. DeClercq et al. (2025) Country: USA | 68 (n = 31 ♀) Aged 7–17, Syrian refugees recruited from primary care during mandatory physical health screening | Disentangle linguistic elements of refugee youths’ trauma narratives and identify biopsychosocial correlates of traumatic stress | Mixed methods analytic approach: Open-ended interview | Semantic analysis of trauma narratives using Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC) | 1. Witnessing violence and loss 2. Discrimination and bullying 3. Separation and/or social anxiety, panic | 7/10 Validity ✓ Clear aims ✓ Appropriate mixed-method approach ✓ Appropriate research design x Appropriate recruitment strategy ✓ Appropriate data collection x Considered reflexivity appropriately Results ✓ Ethical considerations addressed x Rigorous data analysis ✓ Clear statement of findings Utility of results ✓ Value of research |

| 2. Jarlby et al. (2018) Country: Denmark | 7 (n = 7 ♂) Aged 17–18, unaccompanied Refugee from Middle East and Southeast Asia | Explore unaccompanied refugee adolescents’ perspectives on healing and the mental healthcare offered to them when resettled | Semi—structured interviews and Focus-group interview | Data were coded using cross-sectional indexing | 1. Good mental health was associated with social networks and being understood 2. Conventional talk-based therapy re-emerges traumatic events and stigma 3. Healing could come via activities rather than “just talk” (i.e., social, physical, or skill building activities) | 8/10 Validity ✓ Clear aims ✓ Appropriate qualitative methodology ✓ Appropriate research design x Appropriate recruitment strategy ✓ Appropriate data collection x Considered reflexivity appropriately Results ✓ Ethical considerations addressed ✓ Rigorous data analysis ✓ Clear statement of findings Utility of results ✓ Value of research |

| 3. Kronick et al. (2018) Country: Canada | 35 children (20 families) Ages 3–13, pre-school and school aged children, in a medium-security immigration detention centre | Understand the lived experiences of children held in immigration detention | Narrative inquiry via sand play | Sandtray coding themes | 1. Traumatic nature of detention 2. Conflicted understanding of detention and migration 3. Temporal disruption and boredom | 7/10 Validity ✓ Clear aims ✓ Appropriate mixed-method approach ✓ Appropriate research design x Appropriate recruitment strategy ✓ Appropriate data collection x Considered reflexivity appropriately Results ✓ Ethical considerations addressed x Rigorous data analysis ✓ Clear statement of findings Utility of results ✓ Value of research |

| 4. Magan et al. (2024) Country: USA | 15 adolescents (n = 10 ♀) Muslim Rohingya refugee adolescents (ages 12–17), living in urban resettlement | Exploring the mental and emotional health challenges of Rohingya adolescents in the U.S. | Qualitative interview | Thematic analysis | 1. High emotional distress 2. Self-regulation through internal dialogue and faith-based coping 3. Stigma around mental difficulties and cultural silence 4. Need for safe space for youth expression | 6/10 Validity ✓ Clear aims ✓ Appropriate qualitative methodology ✓ Appropriate research design x Appropriate recruitment strategy ✓ Appropriate data collection x Considered reflexivity appropriately Results ✓ Ethical considerations addressed x Rigorous data analysis ✓ Clear statement of findings Utility of results x Value of research |

| 5. Filler et al. (2021) Country: Canada | 7 Adolescents and 8 service providers (gender not provided) Aged 16–19 Syrian refugees | Explore how Syrian refugee adolescents conceptualize mental health through the perspectives of older adolescents and service providers | Grounded theory qualitative exploratory design | Interview comparison | 1. Poorly perceived concept of mental health 2. Identity doubt (retain their cultural and linguistic personal background) 3.Personal facts (anxiety and sadness, lack of family and friends’ relation, and stigma from institution impacted negative mental health) | 8/10 Validity ✓ Clear aims ✓ Appropriate qualitative methodology ✓ Appropriate research design x Appropriate recruitment strategy ✓ Appropriate data collection x Considered reflexivity appropriately Results ✓ Ethical considerations addressed ✓ Rigorous data analysis ✓ Clear statement of findings Utility of results ✓ Value of research |

| 6. Kwon and Lee (2018) Country: South Korea | 4 (n = 4 ♀) Aged 8–9 North Korean attending school in South Korea | How the students perceive their traumatic experiences and how they have overcome such difficulties using wisdom and resilience. | case study method | Group play therapy | 1. Traumatic life experiences (bringing stressful past events) 2. Need for love and affection (nurturing play) 3. Sense of loss and grief Play therapy improved: 1. Self-empowering to self-expression 2. Regulating powerful emotions | 7/10 Validity ✓ Clear aims ✓ Appropriate qualitative methodology ✓ Appropriate research design ✓ Appropriate recruitment strategy ✓ Appropriate data collection x Considered reflexivity appropriately Results ✓ Ethical considerations addressed x Rigorous data analysis x Clear statement of findings Utility of results ✓ Value of research |

| 7. Gušić et al. (2018) Country: Sweden | 40 (n = 19♀) Aged 13–19 | Exploration of dissociative experiences in multi-traumatized war-refugee youth. | Mixed method | Quantitative analysis and verbal descriptions of mental experiences | 1. Common Dissociative experiences 2. Negative self and body perception 3. Depressive mood and emotional dysregulation related 4. Memory disturbances 5. Feelings of non-existence – sense of unreality or loss of presence 6. Suffering around dissociative states | 8/10 Validity ✓ Clear aims ✓ Appropriate mixed-method approach ✓ Appropriate research design x Appropriate recruitment strategy ✓ Appropriate data collection x Considered reflexivity appropriately Results ✓ Ethical considerations addressed ✓ Rigorous data analysis ✓ Clear statement of findings Utility of results ✓ Value of research |

| 8. Hettich and Meurs (2021) Country: Germany | 1 (n = 1 ♂) Aged 18 years old, unaccompanied refugee from Afghanistan | Analyse how an unaccompanied minor refugee perceived the psychosocial support he received after arriving in Germany | Case study: Semi-structured interview | Interdisciplinary interpretation group | 1. Need for self-determination 2. Perception of hosting country state 3. Link to the hosting country society 4. Personal relationships in the hosting country | 8/10 Validity ✓ Clear aims ✓ Appropriate qualitative methodology ✓ Appropriate research design x Appropriate recruitment strategy ✓ Appropriate data collection x Considered reflexivity appropriately Results ✓ Ethical considerations addressed ✓ Rigorous data analysis ✓ Clear statement of findings Utility of results ✓ Value of research |

| 9. Majumder et al. (2019) Country: UK | 15 (2 ♀) Aged 15–18 unaccompanied refugees from Afghanistan, Somalia and Iran presenting symptoms of PTSD, depression, and self-harm | Examine mental health services from the perspective of unaccompanied refugee minors and their careers | Semi-structured interviews | Thematic analysis | 1. Perception of their practitioners (patient, authority figure, gender and ethnic background were basic barriers) 2. Perception of therapies (Did not recognize the benefits from talking therapies, regressing rather than progress) | 8/10 Validity ✓ Clear aims ✓ Appropriate qualitative methodology ✓ Appropriate research design x Appropriate recruitment strategy ✓ Appropriate data collection x Considered reflexivity appropriately Results ✓ Ethical considerations addressed ✓ Rigorous data analysis ✓ Clear statement of findings Utility of results ✓ Value of research |

| 10. Yetim et al. (2025) Country: Turkey | 24 (12 ♀) Aged 12–18 years Syrian refugees during the initial settlement | Examine the unique stressors and coping processes of Syrian immigrant youth and the social networks that support them | Focus-group interviews | Ground Theory Framework: Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis | 1. Life struggle (unequal working conditions, informal work, cost of living) 2. Peer relationships (discrimination, peer bullying, loneliness) 3. Future anxiety (Fear of deportation, inability to access quality education, disbelief in having a profession, hopelessness for becoming qualified) 4. Social barriers (Prejudices, exclusion, inability to benefit from public institutions) 5. Social support (preferably family and religion) | 9/10 Validity ✓ Clear aims ✓ Appropriate qualitative methodology ✓ Appropriate research design ✓ Appropriate recruitment strategy ✓ Appropriate data collection x Considered reflexivity appropriately Results ✓ Ethical considerations addressed ✓ Rigorous data analysis ✓ Clear statement of findings Utility of results ✓ Value of research |

| 11. Abdelhamid et al. (2023) Country: Germany | 47 parents 11 children (gender not provided) Aged 8–17 from Syria, Iraq, Palestine, Afghanistan and Eritrea | Explores the perceptions of refugee parents and children experiencing conflict, migration and resettlement to uncover potentially negative and positive influences on the well-being of refugee children | Semi-structured individual and group interviews | Thematic analysis | 1. Experiencing disruptions to daily life and structure 2. Exposure to violence that brings harm or deconstruction 3. Facing impediments that obstruct progress 4. dealing with affliction 5. Feeling isolated 6. feeling subjected to rejection | 10/10 Validity ✓ Clear aims ✓ Appropriate qualitative methodology ✓ Appropriate research design ✓ Appropriate recruitment strategy ✓ Appropriate data collection ✓ Considered reflexivity appropriately Results ✓ Ethical considerations addressed ✓ Rigorous data analysis ✓ Clear statement of findings Utility of results ✓ Value of research |

| 12. d’Abreu et al. (2021) Country: USA | 7 Adolescents (n = 7 ♂) and 4 parents Aged 14–16 Syrian refugees | Analysis of the acculturation, mental health, and academic experience of Syrian refugee adolescents in the United States | Focus-Group Semi-structured interviews | Thematic analysis | 1. English language literacy (difficulty comprehension in classrooms) 2. Ethnic identity (interaction was easy within groups of same values) 3. Interaction teacher-student (their behaviours being considered culturally misunderstood) 4. School culture and expectations 5. Perceived discrimination 6. Mental health issues related to pressure, exhaustion from school and constant tests). 7.Resiliance and hope (support system, and religion) | 7/10 Validity ✓ Clear aims ✓ Appropriate qualitative methodology ✓ Appropriate research design ✓ Appropriate recruitment strategy ✓ Appropriate data collection x Considered reflexivity appropriately Results ✓ Ethical considerations addressed x Rigorous data analysis x Clear statement of findings Utility of results ✓ Value of research |

| 13. Sleijpen et al. (2017) Country: Netherlands | 21 (n = 8 ♀) Aged 13–20 diagnosed with PTSD refugees from Middle East, Africa, Eastern Europe, and Asia | Identify factors and processes that according to young refugees promote their resilience | Semi-structured interviews | Grounded theory formulation: Comparing codes | 1. Traumatic experience in their country of origin 2. Current stressors such as lack of refugee status 3. Support from their close friends and family and religion 4. Discrimination | 10/10 Validity ✓ Clear aims ✓ Appropriate qualitative methodology ✓ Appropriate research design ✓ Appropriate recruitment strategy ✓ Appropriate data collection ✓ Considered reflexivity appropriately Results ✓ Ethical considerations addressed ✓ Rigorous data analysis ✓ Clear statement of findings Utility of results ✓ Value of research |

| 14. Oztabak (2020) Country: Turkey | 50 (gender not provided) Aged 6–10 refugees from 19 Syrians, and 6 Palestinians, and 25 non-refugee Turkish children | Warfare-and-migration-themed drawings of Syrian and Palestinian children living in Turkey as refugees in comparison to Turkish children’s drawings | Comparative study Art therapy intervention | Thematic analysis | 1. Warfare (bombing, soldiers, weapons) 2. Immigration (bus, trains, turtles (living in a suitcase) 3. Death (graves, injured people) 4.flags (identity 5. Hope (heroes) 6. Despair (Crying, sad faces) 7. Nature (sun, clouds, flowers) | 5/10 Validity ✓ Clear aims ✓ Appropriate qualitative methodology x Appropriate research design ✓ Appropriate recruitment strategy X Appropriate data collection X Considered reflexivity appropriately Results ✓ Ethical considerations addressed x Rigorous data analysis x Clear statement of findings Utility of results ✓ Value of research |

| 15. Al-Shatanawi et al. (2023) Country: Jordan | 20 primary healthcare professionals 20 Schoolteachers 20 Syrian parents 20 Adolescents (gender not specified) Aged 12–17 Syrian refugees | Assess the psychosocial problems and needs and coping mechanisms of Adolescent Syrian refugees in Jordan | Qualitative study Semi-structured interviews | Thematic analysis | 1. Psychosocial problems (stress, depression, isolation, Aggressiveness, Family disintegration, violence, separation from friends) 2. Psychosocial problems gender differences: Syrian adolescents female were at bigger disadvantage then their male counterparts 3. Bullying (verbal and physical forms of bullying) 4. Coping mechanisms 5. Unmet psychosocial and other needs (health services, education, social support) | 10/10 Validity ✓ Clear aims ✓ Appropriate qualitative methodology ✓ Appropriate research design ✓ Appropriate recruitment strategy ✓ Appropriate data collection ✓ Considered reflexivity appropriately Results ✓ Ethical considerations addressed ✓ Rigorous data analysis ✓ Clear statement of findings Utility of results ✓ Value of research |

| 16. Roupetz et al. (2020) Country: Lebanon | 118 (n = 118 ♀) Aged 12–17 Syrian refugees in Lebanon | Married girls may experience additional hardships and thus greater feelings of dissatisfaction in daily life, given their young marriage and responsibilities at home | Mixed methods Auto-recorded Narratives and self-administered questionnaires | Thematic analysis | 1.Education (shame, fear, humiliation and loneliness were consistently related to experiences of discrimination when going to school) 2. Safety Concerns (sexual harassment, kidnapping, family forcing) 3. Peer support (family members, friends, Religious support) 4. Longing for life back in Syria | 9/10 Validity ✓ Clear aims ✓ Appropriate qualitative methodology ✓ Appropriate research design x Appropriate recruitment strategy ✓ Appropriate data collection ✓ Considered reflexivity appropriately Results ✓ Ethical considerations addressed ✓ Rigorous data analysis ✓ Clear statement of findings Utility of results ✓ Value of research |

| 17. Davison et al. (2021) Country: Lebanon | 188 (n = 188 ♀) Aged 13–17 Syrian adolescents | Explore and describe the self-reported unmet needs of Syrian adolescent girls who migrated to Lebanon between 2011 and 2016 | Mixed method Audio-recorded stories | Thematic analysis | 1. Unmet needs (housing, sanitation, crowded spaces) 2. Safety needs (stability, protection law, freedom from fear) 3. Need for love and belonging (family, friends, community or within romantic relationships) | 9/10 Validity ✓ Clear aims ✓ Appropriate qualitative methodology ✓ Appropriate research design x Appropriate recruitment strategy ✓ Appropriate data collection ✓ Considered reflexivity appropriately Results ✓ Ethical considerations addressed ✓ Rigorous data analysis ✓ Clear statement of findings Utility of results ✓ Value of research |

| 18. Khawaja and Schweitzer (2024) Country: Australia | 19 (n = 13 ♀) Aged 15–18 refugees from 12 different countries | Explore sense of identity and experiences among refugee youth in the context of resettlement | Semi-structured interview and drawing the Tree of Life Method | Thematic analysis | 1. Experiencing changes in family roles (loss of parents or relatives) 2. Experience of belonging (discrimination and racial abuse from numerous displacements) 3. Experience of bonds with lost loved ones 4. Dealing with emotions in a new context 5. Experience of self in the context of change | 8/10 Validity ✓ Clear aims ✓ Appropriate qualitative methodology ✓ Appropriate research design x Appropriate recruitment strategy ✓ Appropriate data collection x Considered reflexivity appropriately Results ✓ Ethical considerations addressed ✓ Rigorous data analysis ✓ Clear statement of findings Utility of results ✓ Value of research |

| 19. Bründlmayer et al. (2025) Country: Austria | 28 (n = 6 ♀) Aged <18 African unaccompanied refugees /Gambia, Somalia, Nigeria, Kenya, Ghana, and Eritrea) | Disclose narrative focuses of traumatised unaccompanied refugee minors in order to further identify the specific needs of this particular subgroup | Structured interview | Thematic analysis | 1. War related experiences 2. Present experiences (structure of daily life, personal experience with others, trauma-related levels of distress) 3. Coping strategies (future perspectives, leisure, religion, avoidance & self-control) | 8/10 Validity ✓ Clear aims ✓ Appropriate qualitative methodology ✓ Appropriate research design x Appropriate recruitment strategy ✓ Appropriate data collection x Considered reflexivity appropriately Results ✓ Ethical considerations addressed ✓ Rigorous data analysis ✓ Clear statement of findings Utility of results ✓ Value of research |

| 20. Mattelin et al. (2024) Country: Sweden | 18 (n = 11 ♀) Aged 15–17 refugees from 12 different origins (Bosnia, Syria, Iraq, Iran, United Arab Emirates, Somalia, Eritrea, Gambia, Uganda, Nigeria, Sudan, and Peru) | Capture the shared and varying experiences related to the migration journey and the initial resettlement phase of children recently arriving in Sweden | Semi-structured interviews | Thematic analysis | 1. Longing for the good life that cannot be taken for granted a. Experienced of ordinary childhood (hobbies and leisure time, school and education, organizing everyday life) b. Challenging factors (exposure to adversities and violence, family separation, language difficulties, mental health challenges, difficulties in integrating) 2. Challenged agency and changing rights a. The agency is being tested (Intention for immigration) b. Reaching the full age can change everything (rights and regulations for different age groups) | 8/10 Validity ✓ Clear aims ✓ Appropriate qualitative methodology ✓ Appropriate research design x Appropriate recruitment strategy ✓ Appropriate data collection x Considered reflexivity appropriately Results ✓ Ethical considerations addressed ✓ Rigorous data analysis ✓ Clear statement of findings Utility of results ✓ Value of research |

| 21. Moleiro and Roberto (2021) Country: Portugal | 137 (n = 81 ♀) Aged < 18 years old, from Guinea Conacre (n = 19), Mali (n = 9), Sierra Leone and Congo (n = 8) | Characterize unaccompanied minors and understand the processes of transition into the age of majority using mixed methodologies (quantitative and qualitative), with the help of a survey and autobiographical narratives, as a means of also acknowledging the voice of minors/adults in addressing their trajectories and experiences in the country. | Mixed method: Survey and autobiographical narrative | Thematic analysis | 1. Country of origin (reason for leaving, traveling method, 2. Route to the host country (dangers and threats, resourcefulness in the face of risky situations) 3. Reception and initial experiences in the hosting country (detainment at the airport; first impressions of the hosting country) 4. Legal protection measures (relationships with the entity; request for protection) 5. Protective measures in residential care (experience in residencial care, developing meaningful relationships; school integration) 6. Experience of transition to living independently (Precipitation of autonomy; challenges of financial Independence; aspirations for the future) | 8/10 Validity ✓ Clear aims ✓ Appropriate qualitative methodology ✓ Appropriate research design x Appropriate recruitment strategy ✓ Appropriate data collection x Considered reflexivity appropriately Results ✓ Ethical considerations addressed ✓ Rigorous data analysis ✓ Clear statement of findings Utility of results ✓ Value of research |

| 22. Majumder (2019) Country: UK | 15 (n = 1 ♀) Aged 15–18 unaccompanied refugees from Arab and East African countries | Explore unaccompanied refugee children’s experiences, perceptions and beliefs of mental illness, focusing on stigma. | Semi-structured interviews | Thematic analysis | 1. Negative perceptions of the concept of mental health (lose sense of basic upkeep, hygiene, dressing and hair, locked in hospital or prison, sleeps in the street). 2. Anticipated social implication of suffering from mental illness 3. Denial of mental health (alternative explanation avoiding to see a psychologist) | 5/10 Validity ✓ Clear aims ✓ Appropriate qualitative methodology x Appropriate research design ✓ Appropriate recruitment strategy X Appropriate data collection X Considered reflexivity appropriately Results ✓ Ethical considerations addressed x Rigorous data analysis x Clear statement of findings Utility of results ✓ Value of research |

| 23. Sajdi et al. (2021) Country: Jordan | 15 adolescents (n = 11 disabled adolescents and n = 4 married girls) Aged 10–17 years Syrian refugees in Azraq camp | Exploring the experiences of younger (10–12 years) and older (15–17 years) adolescent girls and boys in Azraq camp in four capability domains: education, voice of agency, bodily integrity and freedom of violence, and psychological well-being | Mixed-method longitudinal design: quantitative research with 4000 adolescents and caregivers and qualitative research with 220 adolescents, caregivers and key informants | Thematic analysis | 1. Education and learning 2. Bodily integrity and freedom from violence (girls report fear of harassment and kidnapping) 3. Voice and agency (conservative social norms given specific to girls regarding movement, acting, dressing code, marriage. 4. Psychosocial wellbeing (painful memories of the war, its impact in them and their siblings) 4. Support system and role model (close relationships with their parents and siblings 5. Access to technologies 6. Mobility in Azraq Camp | 7/10 Validity ✓ Clear aims ✓ Appropriate qualitative methodology ✓ Appropriate research design x Appropriate recruitment strategy ✓ Appropriate data collection x Considered reflexivity appropriately Results ✓ Ethical considerations addressed ✓ Rigorous data analysis x Clear statement of findings Utility of results ✓ Value of research |

| 24. Santinho and Krysanova (2024) Country: Portugal | 9 (n = 6 ♀) Aged 15–18 years old refugee adolescents from 9 different cultural background (Congo, Guinea–Bissau, Senegal, Algeria, Benin, Morocco, Mali, Gambia, and Afghanistan) | Shed light on: the various barriers the minors struggle with during the process of hosting and inclusion, the obstacles we face on our side while conducting research, and art as a dialogue facilitator between cultures and a therapeutic supplementary tool for inclusion | Qualitative design Workshops: drawing and photography | Content analysis | 1. Diversity of background and projects 2. Artistic/creative workshops as a useful tool to express emotions, perceptions and hopes 3. Focus on future & Inclusion rather than just trauma | 4/10 Validity x Clear aims ✓ Appropriate qualitative methodology x Appropriate research design ✓ Appropriate recruitment strategy x Appropriate data collection x Considered reflexivity appropriately Results ✓ Ethical considerations addressed x Rigorous data analysis x Clear statement of findings Utility of results ✓ Value of research |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kulari, G.; Figueiredo, S. Self-Perception of Children and Adolescents’ Refugees with Trauma: A Qualitative Meta-Synthesis of the Literature. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1647. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121647

Kulari G, Figueiredo S. Self-Perception of Children and Adolescents’ Refugees with Trauma: A Qualitative Meta-Synthesis of the Literature. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1647. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121647

Chicago/Turabian StyleKulari, Genta, and Sandra Figueiredo. 2025. "Self-Perception of Children and Adolescents’ Refugees with Trauma: A Qualitative Meta-Synthesis of the Literature" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 12: 1647. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121647

APA StyleKulari, G., & Figueiredo, S. (2025). Self-Perception of Children and Adolescents’ Refugees with Trauma: A Qualitative Meta-Synthesis of the Literature. Behavioral Sciences, 15(12), 1647. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121647