The Power of Self-Compassion and PERMA+4: A Dual-Path Model for Employee Flourishing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedures and Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Analytic Strategy

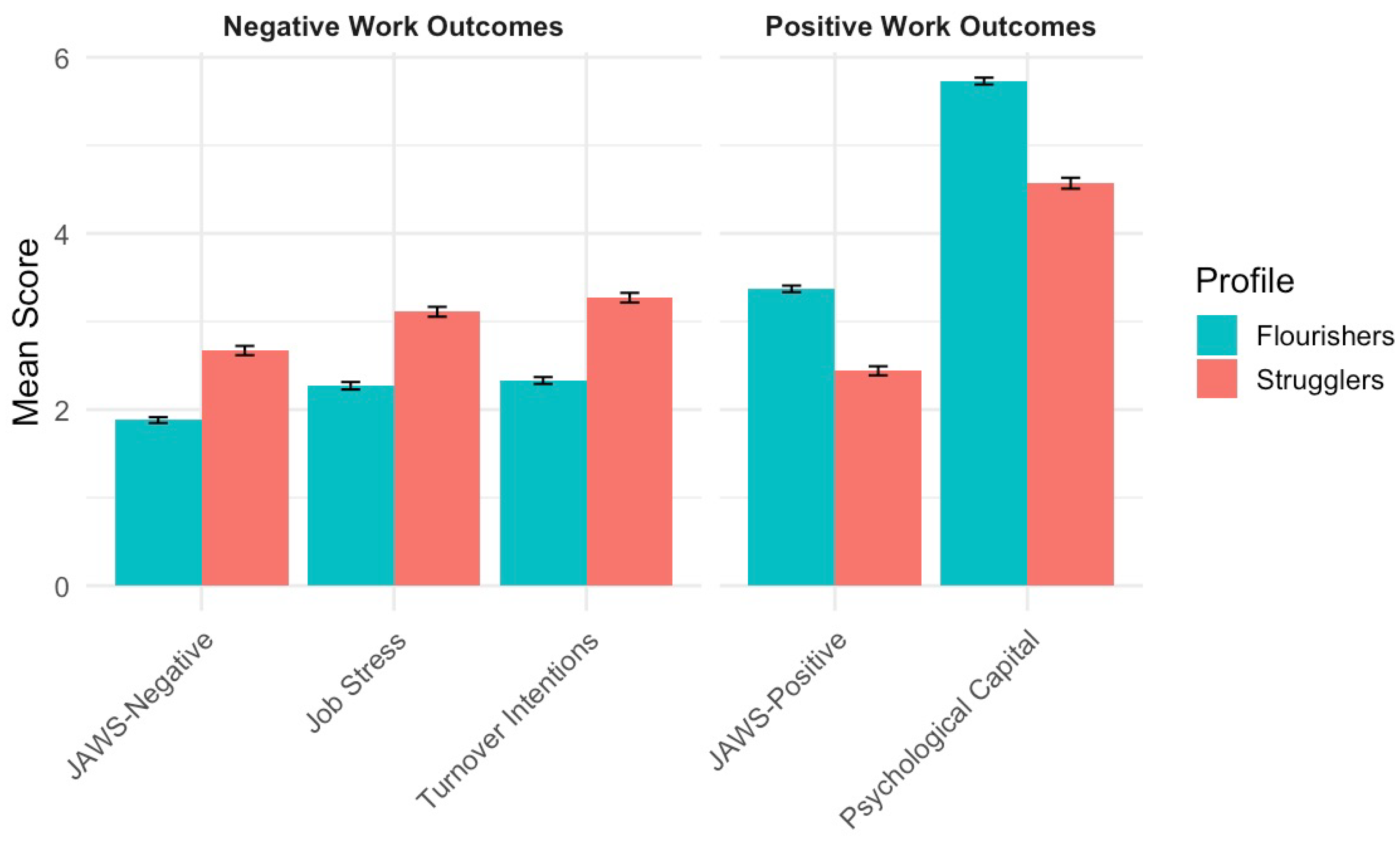

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Benedetto, L., Macidonio, S., & Ingrassia, M. (2024). Well-being and perfectionism: Assessing the mediational role of self-compassion in emerging adults. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 14(5), 1383–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bothma, C. F. C., & Roodt, G. (2013). The validation of the turnover intention scale. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 11(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, M. R., Mack, D. E., Wilson, P. M., & Ferguson, L. J. (2024). Treating yourself in a fairway: Examining the contribution of self-compassion and well-being on performance in a putting task. Sports, 12(11), 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrera, V., & Donaldson, S. I. (2023). PERMA to PERMA+4 building blocks of well-being: A systematic review of the empirical literature. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 19, 510–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodson, S. J., & Heng, Y. T. (2022). Self-compassion in organizations: A review and future research agenda. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 43(2), 168–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, S. I., & Donaldson, S. I. (2021). The positive functioning at work scale: Psychometric assessment, validation, and measurement invariance. Journal of Well-Being Assessment, 4(2), 181–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, S. I., & Donaldson, S. I. (2025). PERMA+4 and positive organizational psychology 2.0. In C. Cooper, S. Patnaik, & R. Rodriguez (Eds.), Advancing positive organizational behaviour. Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, S. I., Donaldson, S. I., McQuaid, M., & Kern, M. L. (2023). The PERMA+4 short scale: A cross-cultural empirical validation using item response theory. International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology, 8, 555–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, S. I., Donaldson, S. I., McQuaid, M., & Kern, M. L. (2024a). Systems-informed PERMA+4 and psychological safety: Predicting work-related well-being and performance across an international sample. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 20, 538–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, S. I., Donaldson, S. I., McQuaid, M., & Kern, M. L. (2024b). Systems-informed PERMA+4: Measuring well-being and performance at the employee, team, and supervisor levels. International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology, 9(2), 1153–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, S. I., & Grant-Vallone, E. J. (2002). Understanding self-report bias in organizational behavior research. Journal of Business and Psychology, 17(2), 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay-Jones, A. L., Rees, C. S., & Kane, R. T. (2015). Self-compassion, emotion regulation and stress among australian psychologists: Testing an emotion regulation model of self-compassion using structural equation modeling. PLoS ONE, 10(7), e0133481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, M., Rothmann, S., & van Zyl, L. (2025). Psychometric validation of the self-compassion scale and the link of self-compassion to managerial flourishing in South Africa. BMC Psychology, 13(1), 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goetz, J. L., Keltner, D., & Simon-Thomas, E. (2010). Compassion: An evolutionary analysis and empirical review. Psychological Bulletin, 136(3), 351–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inceoglu, I., Thomas, G., Chu, C., Plans, D., & Gerbasi, A. (2018). Leadership behavior and employee well-being: An integrated review and a future research agenda. The Leadership Quarterly, 29(1), 179–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, E. G., Hogan, N. L., Camp, S. D., & Ventura, L. A. (2006). The impact of work–family conflict on correctional staff: A preliminary study. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 6(4), 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Avey, J. B., & Norman, S. M. (2007). Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 60, 541–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mróz, J., Toussaint, L., & Kaleta, K. (2024). Association between religiosity and forgiveness: Testing a moderated mediation model of self-compassion and adverse childhood experiences. Religions, 15(9), 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K. D. (2003). Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2(2), 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K. D. (2016). The self-compassion scale is a valid and theoretically coherent measure of self-compassion. Mindfulness, 7(1), 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K. D., & Beretvas, S. N. (2013). The role of self-compassion in romantic relationships. Self and Identity, 12(1), 78–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K. D., Bluth, K., Tóth-Király, I., Davidson, O., Knox, M. C., Williamson, Z., & Costigan, A. (2021). Development and validation of the self-compassion scale for youth. Journal of Personality Assessment, 103(1), 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neff, K. D., Rude, S. S., & Kirkpatrick, K. L. (2007). An examination of self-compassion in relation to positive psychological functioning and personality traits. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(4), 908–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raes, F., Pommier, E., Neff, K. D., & Van Gucht, D. (2011). Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the self-compassion scale. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 18(3), 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reizer, A. (2019). Bringing self-kindness into the workplace: Exploring the mediating role of self-compassion in the associations between attachment and organizational outcomes. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revelle, W. R. (2017). Psych: Procedures for personality and psychological research [Software]. Available online: https://personality-project.org/r/psych/ (accessed on 21 February 2022).

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrucca, L., Fop, M., Murphy, T. B., & Raftery, A. E. (2016). Mclust 5: Clustering, classification and density estimation using gaussian finite mixture models. The R Journal, 8(1), 289–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M. (2018). PERMA and the building blocks of well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 13(4), 333–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sotiropoulou, K., Patitsa, C., Giannakouli, V., Galanakis, M., Koundourou, C., & Tsitsas, G. (2023). Self-compassion as a key factor of subjective happiness and psychological well-being among Greek adults during COVID-19 lockdowns. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(15), 6464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Katwyk, P., Fox, S., Spector, P., & Kelloway, E. (2000). Using the Job-Related Affective Well-Being Scale (JAWS) to investigate affective responses to work stressors. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(2), 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarnell, L. M., & Neff, K. D. (2013). Self-compassion, interpersonal conflict resolutions, and well-being. Self and Identity, 12(2), 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Variable | n or M | % or SD |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 359 | 62.3 |

| Female | 214 | 37.2 |

| Decline to state | 2 | 0.35 |

| Other (e.g., transgender) | 1 | 0.17 |

| Age | 38.9 | 10.1 |

| Education | ||

| Bachelor | 294 | 51.0 |

| Master | 133 | 23.1 |

| Associate | 66 | 11.5 |

| Other (e.g., high school diploma) | 66 | 11.5 |

| Doctorate | 17 | 3.0 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 410 | 71.2 |

| Asian | 53 | 9.2 |

| Hispanic | 45 | 7.8 |

| Black | 44 | 7.6 |

| Multiracial | 24 | 4.2 |

| Industry | ||

| Software & IT services | 100 | 17.4 |

| Other (e.g., military, hospitality) | 82 | 14.2 |

| Education | 66 | 11.5 |

| Retail, wholesale, & distribution | 66 | 11.5 |

| Healthcare | 64 | 11.1 |

| Government | 54 | 9.4 |

| Banking & financial services | 52 | 9.0 |

| Manufacturing | 51 | 8.9 |

| Media & entertainment | 16 | 2.8 |

| Food & beverage | 14 | 2.4 |

| Non-profit | 11 | 1.9 |

| Income | ||

| Decline to state | 2 | 0.30 |

| Less than $25,000 | 86 | 14.9 |

| $25,000–$49,999 | 195 | 33.9 |

| $50,000–$74,999 | 114 | 19.8 |

| $75,000–$99,999 | 91 | 15.8 |

| $100,000–$150,000 | 58 | 10.1 |

| More than $150,000 | 30 | 5.2 |

| Measure | M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PERMA+4 | 5.21 (1.01) | 0.89 | ||||||

| 2. Self-compassion | 3.20 (0.77) | 0.49 | 0.89 | |||||

| 3. Psychological capital | 5.24 (1.01) | 0.73 | 0.51 | 0.89 | ||||

| 4. JAWS-positive | 2.97 (0.87) | 0.68 | 0.41 | 0.59 | 0.89 | |||

| 5. JAWS-negative | 2.22 (0.80) | −0.67 | −0.49 | −0.60 | −0.58 | 0.94 | ||

| 6. Job stress | 2.63 (0.91) | −0.57 | −0.45 | −0.56 | −0.63 | 0.79 | 0.87 | |

| 7. Turnover intentions | 2.73 (0.90) | −0.67 | −0.42 | −0.53 | −0.71 | 0.69 | 0.67 | 0.83 |

| Outcome Variable | Direct Effect | 95% CI (Direct) | Indirect Effect | 95% CI (Indirect) | Total Effect | 95% CI (Total) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PsyCap | 0.63 | [0.56, 0.70] | 0.10 | [0.07, 0.13] | 0.73 | [0.67, 0.79] | 0.562 |

| JAWS-positive | 0.55 | [0.48, 0.61] | 0.04 | [0.00, 0.08] | 0.59 | [0.53, 0.64] | 0.471 |

| JAWS-negative | −0.45 | [−0.51, −0.39] | −0.08 | [−0.11, −0.05] | −0.54 | [−0.58, −0.49] | 0.670 |

| Job stress | −0.44 | [−0.51, −0.36] | −0.10 | [−0.14, −0.06] | −0.53 | [−0.59, −0.47] | 0.587 |

| Turnover intentions | −0.55 | [−0.62, −0.49] | −0.05 | [−0.09, −0.02] | −0.60 | [−0.66, −0.55] | 0.674 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Donaldson, S.I.; Kern, M.L.; Suchta, M.; McQuaid, M.; Donaldson, S.I. The Power of Self-Compassion and PERMA+4: A Dual-Path Model for Employee Flourishing. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1620. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121620

Donaldson SI, Kern ML, Suchta M, McQuaid M, Donaldson SI. The Power of Self-Compassion and PERMA+4: A Dual-Path Model for Employee Flourishing. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1620. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121620

Chicago/Turabian StyleDonaldson, Scott I., Margaret L. Kern, Martin Suchta, Michelle McQuaid, and Stewart I. Donaldson. 2025. "The Power of Self-Compassion and PERMA+4: A Dual-Path Model for Employee Flourishing" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 12: 1620. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121620

APA StyleDonaldson, S. I., Kern, M. L., Suchta, M., McQuaid, M., & Donaldson, S. I. (2025). The Power of Self-Compassion and PERMA+4: A Dual-Path Model for Employee Flourishing. Behavioral Sciences, 15(12), 1620. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121620