Middle School Academic Outcomes Related to Timing of English Language Acquisition in Dual Language Learners

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. DLL Reclassification in School Systems

1.2. Timing of English Proficiency

1.3. Retention

1.4. The Present Study

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Academic Outcomes

2.4. Covariates

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

3.2. Multivariate Analyses

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DLL | Dual Language Learners |

| ESOL | English for Speakers of Other Languages |

| L1 | First Language |

| L2 | Second Language |

| LTEL | Long-Term English Learner |

| GPA | Grade Point Average |

| FRL | Free or Reduced Price Lunch |

| CELLA | Comprehensive English Language Learning Assessment |

| MDCPS | Miami-Dade County Public Schools |

| EL | English Learner |

| M-DCOLPS-R | Miami-Dade County Oral Language Proficiency Scale-Revised |

References

- Abedi, J., & Dietel, R. (2004). Challenges in the no child left behind act for English-language learners. Phi Delta Kappan, 85(10), 782–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AccountabilityWorks. (2015). CELLA: Comprehensive English language learning assessment—2015 test administration manual. Educational Testing Service. Available online: https://www.fldoe.org/core/fileparse.php/7583/urlt/2015cellatestadminmanual.pdf.

- Agirdag, O. (2014). The long-term effects of bilingualism on children of immigration: Student bilingualism and future earnings. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 17(4), 449–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, A., Lόpez, M., Manfra, L., Bleiker, C., Dinehart, L. H. B., Hartman, S. C., & Winsler, A. (2017). Differential third-grade outcomes associated with attending publicly funded preschool programs for low-income Latino children. Child Development, 88(5), 1743–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardasheva, Y., Tretter, T., & Kinny, M. (2012). English language learners and academic achievement: Revisiting the threshold hypothesis. Language Learning, 62(3), 769–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- August, D., & Shanahan, T. (Eds.). (2006). Developing literacy in second-language learners: Report of the National Literacy Panel on Language-Minority Children and Youth. Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman-Perrott, L., Herrera, S., & Murry, K. (2009). Reading difficulties and grade retention: What’s the connection for English language learners? Reading & Writing Quarterly, 26(1), 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, R. (2005). Tracking and high school English learners: Limiting opportunity to learn. American Educational Research Journal, 42(2), 305–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen-Gaddini, M., & Burr, E. (2016). Long-term English learner students: Spotlight on an overlooked population. WestEd. Available online: https://wested2024.s3.us-west-1.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/11165416/LTEL-factsheet.pdf.

- de Jong, E. J. (2004). After exit: Academic achievement patterns of former English language learners. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 12, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, E. R., & Adelson, J. L. (2016). Choosing among multiple achievement measures: Applying multitrait–multimethod confirmatory factor analysis to state assessment, ACT, and student GPA data. Journal of Advanced Academics, 27(1), 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diris, R. (2017). Don’t hold back? The effect of grade retention on student achievement. Education Finance and Policy, 12(3), 312–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, G. J., & Magnuson, K. (2013). The long reach of early childhood poverty. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, P., & Wang, H. (2017). Making English learner reclassification to fluent English proficient attainable or elusive: When meeting criteria is and is not enough. American Educational Research Journal, 55(2), 207–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida Department of Education [FDOE]. (2009). District plan for services to English language learners (ELLs). Available online: http://www.fldoe.org/core/fileparse.php/7586/urlt/0064394-miamidade09.pdf.

- Florida Department of Education [FDOE]: Bureau of Student Achievement Through Language Acquisition. (2015). 2015 Comprehensive English language learning assessment (CELLA) frequently asked questions. Available online: http://www.fldoe.org/core/fileparse.php/7583/urlt/06-05-152015-CELLA-FAQs.pdf.

- García-Pérez, J. I., Hidalgo-Hidalgo, M., & Robles-Zurita, J. A. (2014). Does grade retention affect students’ achievement? Some evidence from Spain. Applied Economics, 46(12), 1373–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guglielmi, R. S. (2008). Native language proficiency, English literacy, academic achievement, and occupational attainment in limited-English-proficient students: A latent growth modeling perspective. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(2), 322–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halle, T., Hair, E., Wandner, L., Mcnamara, M., & Chien, N. (2012). Predictors and outcomes of early versus later English language proficiency among English language learners. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 27, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanover Research. (2017). Effective interventions for long-term English learners. Available online: https://portal.ct.gov/-/media/SDE/ESSA-Evidence-Guides/Effective_Interventions_for_Long-Term_English_Learners.

- Hughes, J. N., West, S. G., Kim, H., & Bauer, S. S. (2018). Effect of early grade retention on school completion: A prospective study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 110(7), 974–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Resources Research Organization & Harcourt Assessment. (2006). Technical report For 2006 FCAT test administrations. Available online: http://www.fldoe.org/core/fileparse.php/7478/urlt/0065575-fc06tech.pdf.

- Jiménez-Castellanos, O., Blanchard, J., Atwill, K., & Jiménez-Silva, M. (2014). Beginning English literacy development and achievement among Spanish-speaking children in Arizona’s English-only classrooms: A four-year two-cohort longitudinal study. International Multilingual Research Journal, 8(2), 104–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieffer, M. (2008). Catching up or falling behind? Initial English proficiency, concentrated poverty, and the reading growth of language minority learners in the United States. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100, 851–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieffer, M. (2012). Early oral language and later reading development in Spanish-speaking English language learners: Evidence from a nine-year longitudinal study. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 33(3), 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieffer, M. J., & Parker, C. E. (2016). Patterns of English learner student reclassification in New York City public schools (REL 2017–200). U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Regional Educational Laboratory Northeast & Islands. Available online: https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/rel/.

- Kim, Y., Curby, T., & Winsler, A. (2014). Child, family, and school characteristics related to English proficiency development among low-income, dual language learners. Developmental Psychology, 50(12), 2600–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kretschmann, J., Vock, M., Lüdtke, O., Jansen, M., & Gronostaj, A. (2019). Effects of grade retention on students’ motivation: A longitudinal study over 3 years of secondary school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(8), 1432–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. H., & Macaro, E. (2013). Investigating age in the use of l1 or English-only instruction: Vocabulary acquisition by Korean EFL learners. The Modern Language Journal, 97(4), 887–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesaux, N. K., Rupp, A. A., & Siegel, L. S. (2007). Growth in reading skills of children from diverse linguistic backgrounds: Findings from a 5-year longitudinal study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(4), 821–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindholm-Leary, K., & Hernández, A. (2011). Achievement and language proficiency of Latino students in dual language programmes: Native English speakers, fluent English/previous ELLs, and current ELLs. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 32(6), 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llosa, L. (2012). Assessing English learners’ progress: Longitudinal invariance of a standards-based classroom assessment of English proficiency. Language Assessment Quarterly, 9(4), 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, V., & Sparks, J. (2019). Who gets held back? An analysis of grade retention using stratified frailty models. Population Research and Policy Review, 38, 695–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miami-Dade County Public Schools. (2018). English language learners and their academic and English language acquisition progress: 2017–2018. Available online: http://drs.dadeschools.net/AdditionalReports/M258%20-%20ATTACHMENT%20-%20Transmittal%20of%20Report%20-%20ELL%20%20their%20Academic%20Progress%2017-18.pdf.

- Migration Policy Institute. (2025). Young dual language learners in the United States and by state. Available online: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/programs/data-hub/charts/us-state-profiles-young-dlls.

- Miller, E. (2017). Spanish instruction in head start and dual language learners’ academic achievement. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 52, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosqueda, E., & Maldonado, S. I. (2013). The effects of English language proficiency and curricular pathways: Latina/os’ mathematics achievement in secondary schools. Equity & Excellence in Education, 46(2), 202–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Education Statistics [NCES]. (2023). English learners in public schools. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cgf/english-learners.

- National Conference of State Legislatures [NCSL]. (2018). Dual- and English-language learners. Available online: https://www.ncsl.org/research/education/english-dual-language-learners.aspx.

- O’Connor, M., O’Connor, E., Tarasuik, J., Gray, S., Kvalsvig, A., & Goldfeld, S. (2018). Academic outcomes of multilingual children in Australia. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20(4), 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onda, M., & Seyler, E. (2020). English learners reclassification and academic achievement: Evidence from Minnesota. Economics of Education Review, 79, 102043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, S. F. (2018). The widening academic achievement gap between the rich and the poor. In D. B. Grusky (Ed.), Social stratification: Class, race, and gender in sociological perspective (4th ed., pp. 536–550). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Reardon, S. F., & Galindo, C. (2007). Patterns of Hispanic students’ math skill proficiency in the early elementary grades. Journal of Latinos and Education, 6(3), 229–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, G., Mohammed, S., & Vaughn, S. (2010). Reading achievement across three language groups: Growth estimates for overall reading and reading subskills obtained with the Early Childhood Longitudinal Survey. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(3), 668–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, L. D., McMahon, S. D., & Jason, L. A. (2018). The Role of neighborhood context and school climate in school-level academic achievement. American Journal of Community Psychology, 61(3–4), 296–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, W., & Marcelletti, D. (2013). The gap that can’t go away: The catch-22 of reclassification in monitoring the progress of English Learners. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 35(2), 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafini, E. J., Rozell, N., & Winsler, A. (2022). Academic and English language outcomes for DLLs as a function of school bilingual education model: The role of two-way immersion and home language support. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 25(2), 552–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkey, J., & Layzer, C. (2000). Whose definition of success? Identifying factors that affect English language learners’ access to academic success and resources. TESOL Quarterly, 34(2), 352–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, N. (2024). Raising the bar: How revising an English language proficiency assessment for initial English learner classification affects students’ later academic achievements. Educational Assessment, 29(2), 75–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slama, R. (2012). A longitudinal analysis of academic English proficiency outcomes for adolescent English language learners in the United States. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(2), 265–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spack, R. (2004). The acquisition of academic literacy in a second language: A longitudinal case study, updated. In V. Zamel, & R. Spack (Eds.), Crossing the curriculum: Multilingual learners in college classrooms (pp. 19–45). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Steele, J. L., Slater, R. O., Zamarro, G., Miller, T., Li, J., Burkhauser, S., & Bacon, M. (2017). Effects of dual-language immersion programs on student achievement: Evidence from lottery data. American Educational Research Journal, 54(Suppl. 1), 282S–306S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabors, P., Páez, M., & Lopez, L. (2003). Dual language abilities of bilingual four-year olds: Initial findings from the early childhood study of language and literacy development of Spanish-speaking children. NABE Journal of Research and Practice, 1(1), 70–91. [Google Scholar]

- Tavassolie, T., & Winsler, A. (2019). Predictors of mandatory 3rd grade retention from high-stakes test performance for low-income, ethnically diverse children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 48, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, K. (2017). English learners’ time to reclassification: An analysis. Educational Policy, 31(3), 330–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillman, K., Guo, G., & Harris, K. (2006). Grade retention among immigrant children. Social Science Research, 35(1), 129–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Education. (2016). Educational experiences of English learners: Grade retention, high school graduation, and GED attainment, 2011–12. Available online: https://www2.ed.gov/rschstat/eval/title-iii/crdc-retention-completion.pdf.

- Valentino, R., & Reardon, S. (2015). Effectiveness of four instructional programs designed to serve English learners: Variation by ethnicity and initial English proficiency. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 37(4), 612–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willson, V., & Hughes, J. (2006). Retention of Hispanic/Latino students in first grade: Child, parent, teacher, school, and peer predictors. Journal of School Psychology, 44(1), 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winsler, A., Burchinal, M., Tien, H.-C., Peisner-Feinberg, E., Espinosa, L., Castro, D., LaForett, D., Kim, Y., & De Feyter, J. (2014). Early development among dual language learners: The roles of language use at home, maternal immigration, country of origin, and socio-demographic variables. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 29(4), 750–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winsler, A., Díaz, R. M., Espinosa, L., & Rodríguez, J. L. (1999). When learning a second language does not mean losing the first: Bilingual language development in low-income, Spanish-speaking children attending bilingual preschool. Child Development, 70(2), 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winsler, A., Hutchison, L. A., De Feyter, J. J., Manfra, L., Bleiker, C., Hartman, S. C., & Levitt, J. (2012). Child, family, and childcare predictors of delayed school entry and kindergarten retention among linguistically and ethnically diverse children. Developmental Psychology, 48(5), 1299–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winsler, A., Rozell, N., Tucker, T. L., & Norvell, G. (2023). Earlier mastery of English predicts 5th grade academic outcomes for low-income dual language learners in Miami, USA. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 1–14, Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winsler, A., Tran, H., Hartman, S., Madigan, A., Manfra, L., & Bleiker, C. (2008). School readiness gains made by ethnically diverse children in poverty attending center-based childcare care and public school pre-kindergarten programs. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 23, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaff, J., Margolius, M., Varga, S., Lynch, A., Tang, C., & Donlan, A. (2020). English learners and high school graduation: A pattern-centered approach to understand within-group variations. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Grade of ESOL Exit | n | % of Total | Total # of Years in ESOL | n | % of Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K | 4358 | 29.3% | 1 | 4296 | 28.9% |

| G1 | 3590 | 24.2% | 2 | 3410 | 23% |

| G2 | 2724 | 18.3% | 3 | 2600 | 17.5% |

| G3 | 2265 | 15.3% | 4 | 2441 | 16.4% |

| G4 | 358 | 2.4% | 5 | 490 | 3.3% |

| G5 | 338 | 2.3% | 6 | 289 | 1.9% |

| G6 | 558 | 3.8% | 7 | 382 | 2.2% |

| G7 | 592 | 4.0% | 8 | 613 | 4.1% |

| G8 | 69 | 0.5% | 9 | 301 | 2% |

| - | - | - | 10 | 30 | 0.2% |

| Total | 14,852 | 100% | Total | 14,852 | 100% |

| GPA | Reading | Math | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | B | SE (B) | B | SE (B) | B | SE (B) |

| Intercept | 4.38 | 0.028 | 3.92 | 0.053 | 3.06 | 0.073 |

| Male | −0.253 ** | 0.014 | −0.154 ** | 0.021 | 0.061 * | 0.024 |

| White vs. Latino | 0.184 ** | 0.032 | 0.224 ** | 0.055 | 0.291 ** | 0.075 |

| Black vs. Latino | −0.171 ** | 0.047 | −0.422 ** | 0.051 | −0.254 ** | 0.062 |

| Poverty | −0.278 ** | 0.022 | −0.415 ** | 0.039 | −0.377 ** | 0.048 |

| Disability | −0.125 ** | 0.024 | −0.848 ** | 0.038 | −0.606 ** | 0.037 |

| Years in ESOL | −0.033 ** | 0.004 | −0.141 ** | 0.006 | −0.072 ** | 0.008 |

| Years in ESOL × Black/Latino a | 0.002 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.015 | −0.016 | 0.017 |

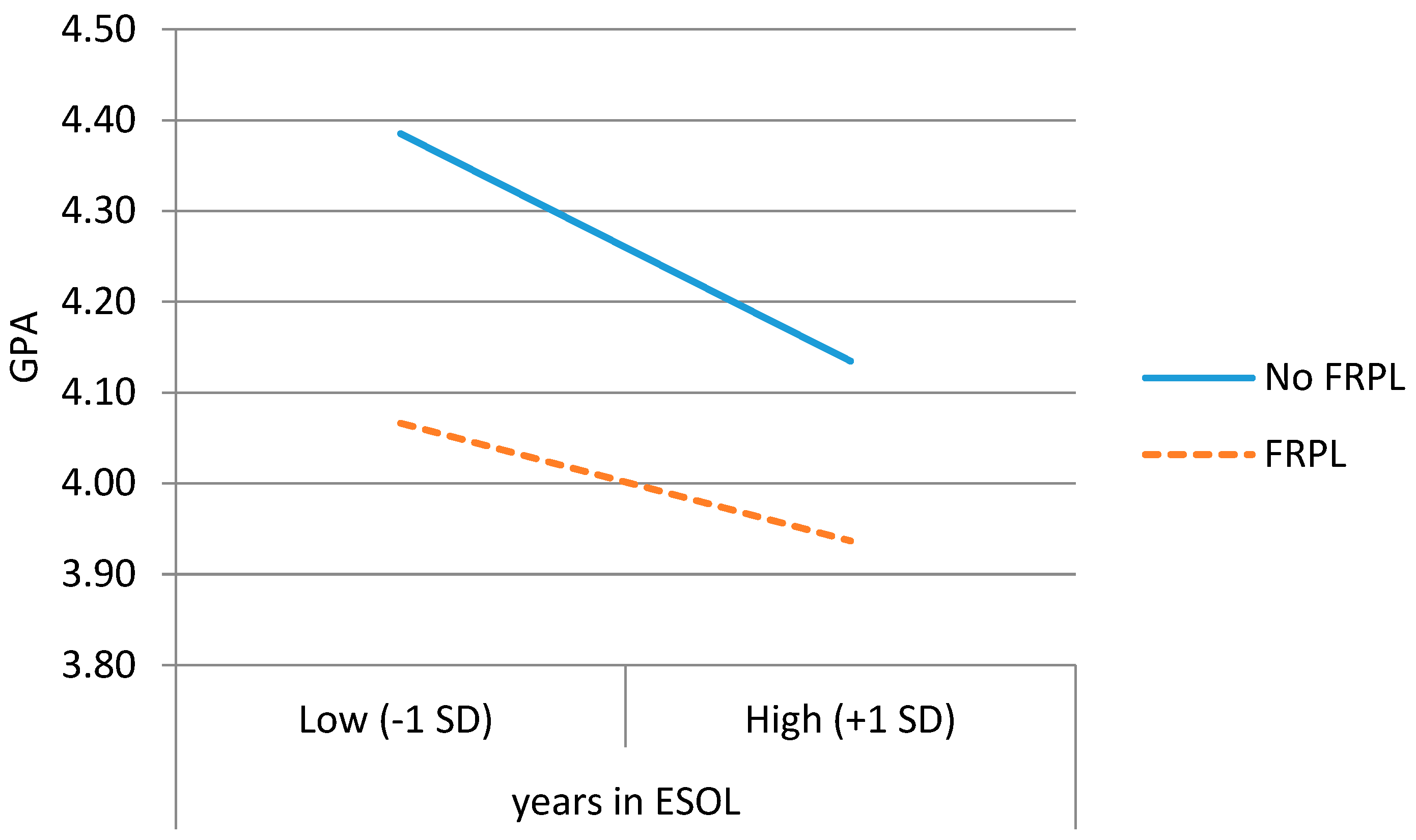

| YearsESOL× Poverty a | 0.029 ** | 0.008 | 0.039 * | 0.015 | 0.050 * | 0.022 |

| Variable | Odds Ratio | SE |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 3.082 ** | 0.219 |

| White vs. Latino | 0.328 | 1.02 |

| Black vs. Latino | 1.022 | 0.377 |

| Poverty | 2.111 | 0.381 |

| Disability | 1.147 | 0.295 |

| Total Years in ESOL | 1.118 * | 0.052 |

| Years in ESOL × Black/Latino a | 1.101 | 0.096 |

| Years in ESOL × Poverty a | 0.705 * | 0.141 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Norvell, G.; Tucker, T.L.; Winsler, A. Middle School Academic Outcomes Related to Timing of English Language Acquisition in Dual Language Learners. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1612. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121612

Norvell G, Tucker TL, Winsler A. Middle School Academic Outcomes Related to Timing of English Language Acquisition in Dual Language Learners. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1612. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121612

Chicago/Turabian StyleNorvell, Gabriele, Tevis L. Tucker, and Adam Winsler. 2025. "Middle School Academic Outcomes Related to Timing of English Language Acquisition in Dual Language Learners" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 12: 1612. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121612

APA StyleNorvell, G., Tucker, T. L., & Winsler, A. (2025). Middle School Academic Outcomes Related to Timing of English Language Acquisition in Dual Language Learners. Behavioral Sciences, 15(12), 1612. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121612